- Mi'kmaq hieroglyphic writing

-

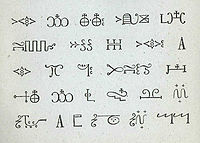

Míkmaq hieroglyphs

komqwejwi'kasikl

Type logographic Languages Mi'kmaq Time period 17th–19th century (logographic); date of precursors unknown Note: This page may contain IPA phonetic symbols. Míkmaq hieroglyphic writing was a writing system and memory aid used by the Míkmaq, a Native American people of the east coast of what is now Canada.

The missionary-era glyphs were logograms, with phonetic elements used alongside (Schmidt & Marshall 1995), which included logographic, alphabetic,[citation needed] and ideographic[citation needed] information. They were derived from a pictograph and petroglyph tradition.[1] In Mi'kmaq the glyphs are called komqwejwi'kasikl, or "sucker-fish writings", which refers to the tracks the sucker fish leaves on the muddy river bottom.

Contents

Classification

Scholars have debated whether the earliest known Míkmaq "hieroglyphs" from the 17th century qualified fully as a writing system, rather than as a pictographic mnemonic device. In the 17th century, French missionary Chrétien Le Clercq adapted the Míkmaq characters as a logographic system for pedagogical purposes.

In 1978, Ives Goddard and William Fitzhugh of the Department of Anthropology at the Smithsonian Institution, contended that the pre-missionary system was purely mnemonic, as it could not be used to write new compositions. Schmidt and Marshall argued in 1995 that the missionary system of the 17th century was able to serve as a fully functional writing system. This would mean that Míkmaq is the oldest writing system for a native language north of Mexico.

Text of the Rite of Confirmation in Míkmaq hieroglyphs. The text reads Koqoey nakla ms

Text of the Rite of Confirmation in Míkmaq hieroglyphs. The text reads Koqoey nakla msit telikaqumilálaji? – literally 'Why / those / all / after he did that to them?', or "Why are all these different steps necessary?"History

Father le Clercq, a Roman Catholic missionary on the Gaspé Peninsula in New France from 1675, claimed that he had seen some Míkmaq children 'writing' symbols on birchbark as a memory aid. This was sometimes done by pressing porcupine quills directly into the bark in the shape of symbols. Le Clercq adapted those symbols to writing prayers, developing new symbols as necessary.

This adapted writing system proved popular among Míkmaq, and was still in use in the 19th century. Since there is no historical or archaeological evidence of these symbols from before the arrival of this missionary, it is unclear how ancient the use of the mnemonic glyphs was. The relationship of these symbols with Míkmaq petroglyphs is also unclear.

Pierre Maillard, Roman Catholic priest, during the winter of 1737-38[2] perfected a system of hieroglyphics to transcribe Mi'kmaq words. He used these symbols to write formulas for the principal prayers and the responses of the faithful, in the catechism, so his followers might learn them more readily. In this development he was greatly aided by Jean-Louis Le Loutre, another French missionary. There is no direct evidence that Maillard was aware of Le Clercq's work; in any event Maillard's work is outstanding in that he left numerous works in the language, which continued in use among the Mi'kmaq into the 20th century.[3][4]

The Fell hypothesis

Biologist and epigrapher Barry Fell, who claimed that various pre-Columbian inscriptions in the Americas were written by Europeans, argued that Míkmaq hieroglyphic writing was not only pre-Columbian but Egyptian in origin. Mainstream epigraphers and others rejected Fell's claims as baseless. (Goddard & Fitzhugh, Schmidt & Marshall). A web page called Egyptians in Acadia offers an illustration of some of Fell's claims (apparently taken from Fell 1992 (cited on that same page). Comparison with the Egyptian hieroglyphs shows that Fell's claims have significant shortcomings. The description below describes the facts of the use of the Egyptian Hieroglyphs which Fell cited.

Table from Fell

Egyptian

HieroglyphsDescription of Egyptian Hieroglyphs mentioned by Fell and their uses in Egyptian

Fell's drawing of the Egyptian hieroglyph is not accurate. F35 represents the "heart and windpipe" of a vertebrate animal. F35 is used as shown with phonetic determinatives I9 f 'adder' and D21 r 'mouth' in the word nfr 'good'. When three F35s are used together, it means 'beauty' in Egyptian. Egyptian words meaning 'truth' do not use F35. The Micmac glyph cited by Fell appears not to be an Egyptian Hieroglyph, but rather the Christian symbol Globus cruciger with the Earth (a crossed circle) surmounted by a cross.

The Hieroglyph N14 is a star; when used alone, it means sb3 'star'; the centre example with N11 j'h 'moon' above the star means 3bd 'month'; the rightmost example, shown with N1 pt 'sky' above the star does not occur. The Egyptian words for 'heaven' and 'sky' do not use the star hieroglyph. The Micmac glyph cited by Fell appears to be an ordinary pentagram star used for 'heaven'; no connection to Egypt is necessary for the Micmac sign to make sense in this context.

The Hieroglyph V30 represents wickerwork-basket; it is used in the Egyptian word nb 'all'. The Míkmaq ms it 'all' (not 'full'?) is not drawn accurately; it is a large equilateral triangle made up of horizontal lines, not a low horizontal sign like V30. (See the example in the Text of the Rite of Confirmation above.) It appears unlikely that Micmac msit and Egyptian nb are related.

The Hieroglyph O41 represents a double-stairway; it is used in the Egyptian word q3y 'ascent', 'high place', j'r 'ascend'. O41 does not mean 'exalted one' in Egyptian. The Micmac glyph cited by Fell appears to be a triangle, representing the Trinity, and not a set of stairs. Examples

The beginning of the Lord's Prayer in Míkmaq hieroglyphs. The text reads Nujjinen wásóq – "Our father / in heaven"External links

- Míkmaq Portraits Collection Includes tracings and images of Míkmaq petroglyphs

- Micmac at ChristusRex.org A large collection of scans of prayers in Míkmaq hieroglyphs.

- Écriture sacrée en Nouvelle France: Les hiéroglyphes micmacs et transformation cosmologique (PDF, in French) A discussion of the origins of Míkmaq hieroglyphs and sociocultural change in the 17th century Micmac society.

References

- Fell, Barry. 1992. "The Micmac Manuscripts" in Epigraphic Society Occasional Papers, 21:295.

- Goddard, Ives, and William W. Fitzhugh. 1978. "Barry Fell Reexamined", in The Biblical Archaeologist, Vol. 41, No. 3. (September), pp. 85–88.

- Hewson, John. 1982. Micmac Hieroglyphs in Newfoundland. Languages in Newfoundland and Labrador, ed. by Harold Paddock, 2nd ed., 188-199. St John's, Newfoundland: Memorial University.

- Hewson, John. 1988. Introduction to Micmac Hieroglyphics. Cape Breton Magazine 47:55-61. (text of 1982, plus illustrations of embroidery and some photos)

- Kauder, Christian. 1921. Sapeoig Oigatigen tan teli Gômgoetjoigasigel Alasotmaganel, Ginamatineoel ag Getapefiemgeoel; Manuel de Prières, instructions et changs sacrés en Hieroglyphes micmacs; Manual of Prayers, Instructions, Psalms & Hymns in Micmac Ideograms. New edition of Father Kauder's Book published in 1866. Ristigouche, Québec: The Micmac Messenger.

- Lenhart, John. History relating to Manual of prayers, instructions, psalms and humns in Micmac Ideograms used by Micmac Indians fof Eastern Canada and Newfoundland. Sydney, Nova Scotia: The Nova Scotia Native Communications Society.

- Schmidt, David L., and B. A. Balcom. 1995. "The Règlements of 1739: A Note on Micmac Law and Literacy", in Acadiensis. XXIII, 1 (Autumn 1993) pp 110–127. ISSN 0044-5851

- Schmidt, David L., and Murdena Marshall. 1995. Míkmaq Hieroglyphic Prayers: Readings in North America's First Indigenous Script. Nimbus Publishing. ISBN 1-55109-069-4

- ^ Edwards, Brandan Frederick R. Paper Talk: A History of Libraries, Print Culture, and Aboriginal Peoples in Canada before 1960. Toronto: The Scarecrow Press, Inc. 2004 ISBN 978-0810851139 p.11 [1]

- ^ Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online, MAILLARD (Maillart, Mayard, Mayar), PIERRE accessed 4 October 2009

- ^ This hieroglyphic script contained more than 5700 different picture letters to speak to their imagination . . he wrote the first Micmac grammar and dictionary, he produced religious handbooks containing prayers, hymns, sermons and forms for celebrating baptisms, marriages and funerals. When the government no longer allowed resident missionaries to work among the people, their chiefs would gather them . . read Fr. Maillard's "sacred text" . . Fr. Pat Fitzpatrick CSSp, Spiritan Missionary News Oct. 1994, accessed 4 October 2009

- ^ As late as 1927 it could be written, "The Micmac book has taken the place of a missionary for nearly a hundred and seventy years". Spiritans

Categories:- Mi'kmaq

- Hieroglyphs

- Logographic writing systems

- Native American culture

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.