- Least weasel

-

Least weasel

Temporal range: Late Pleistocene–Recent

Middle European weasel (Mustela nivalis vulgaris) at the British Wildlife Centre, Surrey, England Conservation status Scientific classification Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Class: Mammalia Order: Carnivora Family: Mustelidae Subfamily: Mustelinae Genus: Mustela Species: M. nivalis Binomial name Mustela nivalis

Linnaeus, 1766

Least weasel range The least weasel (Mustela nivalis) is the smallest member of the Mustelidae (as well as the smallest of the Carnivora), native to Eurasia, North America and North Africa, though it has been introduced elsewhere. It is classed as Least Concern by the IUCN, due to its wide distribution and presumably large population.[1] Despite its small size, the least weasel is a fierce hunter, capable of killing a rabbit 5-10 times its own weight.[2]

Contents

Evolution

Within the genus Mustela, the least weasel is a relatively unspecialised form, as evidenced by its pedomorphic skull, which occurs even in large subspecies.[3] Its direct ancestor was Mustela praenivalis, which lived in Europe during the Middle Pleistocene and Villafranchian. M. praenivalis itself was probably preceded by M. pliocaenica of the Pliocene. The modern species probably arose during the Late Pleistocene.[4] The least weasel is the product of a process begun 5-7 million years ago, when northern forests were replaced by open grassland, thus prompting an explosive evolution of small, burrowing rodents. The weasel's ancestors were larger than the current form, and underwent a reduction in size to exploit the new food source. The least weasel thrived during the Ice Age, as its small size and long body allowed it to easily operate beneath snow, as well as hunt in burrows. It probably crossed to North America through the Bering land bridge 200,000 years ago.[5]

Subspecies

The least weasel has a high geographic variation, a fact which has historically led to numerous disagreements among biologists studying its systematics. Least weasel subspecies are divided into 3 categories:[6]

- The pygmaea-rixosa group (small weasels): Tiny weasels with short tails and pedomorphic skulls, which turn pure white in winter. They inhabit northern European Russia, Siberia, the Russian Far East, Finland, northern Scandinavian Peninsula, Mongolia, northeastern China, Japan and North America.

- The boccamela group (large weasels): Very large weasels with large skulls, relatively long tails and lighter coloured pelts. Locally, they either do not turn white or only partially in winter. They inhabit Transcaucasia, from western Kazakhstan to Semirechye and in the flat deserts of Middle Asia.

- The nivalis group (average weasels): Medium-sized weasels, with tails of moderate length, representing a transitional form between the former two groups. They inhabit the middle and southern regions of European Russia, Crimea, Ciscaucasus, western Kazakhstan, southern and middle Urals and montane parts of Middle Asia, save for Koppet Dag.

As of 2005[update],[7] 18 subspecies are recognised.

Subspecies Trinomial authority Description Range Synonyms Common weasel

Mustela n. nivalisLinnaeus, 1766 A medium sized subspecies with a tail of moderate length, constituting about 20-21% of its body length. In its summer fur, the upper body is dark-brownish or chestnut colour, while its winter fur is pure white. It is probably a transitional form between the small pygmaea and large vulgaris[8] Middle regions of European Russia, from the Baltic states to the middle and southern Urals, northward approximately to the latitude of Saint Petersburg and Perm, and south to the Kursk and Voronezh Oblasts. Outside the former Soviet Union, its range includes northern Europe save for Finland and parts of the Scandinavian Peninsula caraftensis (Kishida, 1936)

kerulenica (Bannikov, 1952)

punctata (Domaniewski, 1926)

yesoidsuna (Kishida, 1936)Mustela n. allegheniensis Rhoads, 1901 Southeastern USA (Michigan, Pennsylvania, Virginia, North Carolina, Ohio, Illinois, Wisconsin) Transcaucasian weasel

Mustela n. boccamelaBechstein, 1800 A very large subspecies, with a long tail constituting about 30% of its body length. In its summer fur, the upper body is light brownish or chestnut with yellowish or reddish tints, with some individuals having a brownish dot on the corners of the mout and sometimes on the chest and belly. The winter fur is not pure white, being usually dirty white with brown patches[9] Transcaucasia, southern Europe, Asia Minor and probably western Iran italicus (Barrett-Hamilton, 1900) Mustela n. campestris Jackson, 1913 Southwestern USA (South Dakota, Iowa, Nebraska) Mustela n. caucasica Barrett-Hamilton, 1900 dinniki (Satunin, 1907) Mustela n. eskimo Stone, 1900 Alaska Turkmenian weasel

Mustela n. heptneriMorozova-Turova, 1953 A very large subspecies with a long tail constituting about 25-30% of its body length. In its summer fur, the upper body is very light sandy brown or pale-yellowish. The fur is short, sparse and coarse, and does not turn white in winter[10] Semideserts and deserts of southern Kazakhstan and Middle Asia from the Caspian Sea to Semirechye, southern Tajikistan, Koppet Dag, Afghanistan and northeastern Iran Korean weasel

Mustela n. mosanensisMori, 1927 Korean Peninsula Japanese weasel

Mustela n. namiyeiKuroda, 1921 Japan Mediterranean weasel

Mustela n. numidicaPucheran, 1855 Morocco, Algeria, Malta, Azores Islands and Corsica albipes (Mina Palumbo, 1868)

algiricus (Thomas, 1895)

atlas (Barrett-Hamilton, 1904)

corsicanus (Cavazza, 1908)

fulva (Mina Palumbo, 1908)

galanthias (Bate, 1905)

ibericus (Barrett-Hamilton, 1900)

meridionalis (Costa, 1869)

siculus (Barrett-Hamilton, 1900)Montane Turkestan weasel

Mustela n. pallidaBarrett-Hamilton, 1900 A medium sized subspecies with a tail constituting about 24% of its body length. The colour of the summer fur is light-brownish, while the winter fur is white[11] Montane parts of Turkmenia, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kazakhstan and Kirgizia, as well as Chinese parts of the same mountain systems and perhaps in the extreme eastern parts of Hindukush Siberian least weasel

Mustela n. pygmaeaJ. A. Allen, 1903 A very small subspecies, with a short tail which constitutes about 13% of its body length. In its summer coat, the dorsal colour is dark-brown or reddish, while the winter fur is entirely white[12] All of Siberia, except southern nd southeastern Transbaikalia; northern and middle Urals, northern Kazakhstan and the Russian Far East including Sakhalin and Kuril Islands, European Russia westwards to the Kola Peninsula and southwards to the northern parts of the Kirovsky and Gorkovsk districts. Outside of the former USSR, its range includes Finland, northern Scandinavian and Korean Peninsulas, all of Mongolia save for the eastern part and probably northeastern China kamtschatica (Dybowksi, 1922) Bangs' weasel

Mustela n. rixosaBangs, 1896 The smallest subspecies. In its summer coat, the fur is dark reddish brown, while the winter fur is pure white[13] Mackenzie, Labrador, Quebec, Minnesota, North Dakota, Montana, Saskatchewan, Alberta, British Columbia Mustela n. rossica Abramov and Baryshnikov, 2000 Sichuan weasel

Mustela n. russellianaThomas, 1911 Sichuan, southern China Mustela n. stoliczkana Blanford, 1877 Kashgaria Vietnamese weasel

Mustela n. tonkinensisBjörkegren, 1941 Northern and southern Vietnam Middle-European weasel

Mustela n. vulgarisErxleben, 1777 A somewhat larger subspecies than nivalis, with a longer tail which constitutes about 27% of its body length. In its summer fur, the upper body varies from being light-brownish to dark-chestnut, while the winter fur is white in its northern range and piebald in its souther range[14] Southern European Russia from the latitude of southern Voronezh and Kursk districts, Crimea, Ciscaucasia, northern slope of the main Caucasus, eastward to the Volga. Outside the former Soviet Union, its range includes Europe southward to the Alps and Pyrenees dumbrowskii (Matschie, 1901)

hungarica (Vásárhelyi, 1942)

minutus (Pomel, 1853)

monticola (Cavazza, 1908)

nikolskii (Semenov, 1899)

occidentalis (Kratochvil, 1977)

trettaui (Kleinschmidt, 1937)

vasarhelyi (Kretzoi, 1942)Physical description

Skulls of a long-tailed weasel (top), a stoat (bottom left) and least weasel (bottom right), as illustrated in Merriam's Synopsis of the Weasels of North America

Skulls of a long-tailed weasel (top), a stoat (bottom left) and least weasel (bottom right), as illustrated in Merriam's Synopsis of the Weasels of North America

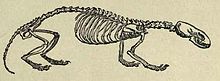

The least weasel has a thin, greatly elongated and extremely flexible body with a small, yet elongated, blunt muzzled head which is no thicker than the neck. The eyes are large, bulging and dark coloured. The legs and tail are relatively short, the latter constituting less than half its body length. The feet are armed with sharp, dark claws, and the soles are heavily haired.[15] The skull, especially that of the small rixosa group, has an infantile appearance when compared with that of other members of the genus Mustela (in particular, the stoat and kolonok). This is expressed in the relatively large size of the cranium and shortened facial region.[16] The skull is, overall, similar to that of the stoat, but smaller, though the skulls of large male weasels tend to overlap in size with those of small female stoats.[17] It usually has 4 pairs of nipples, but these are only visible in females. The baculum is short (16–20 mm), with a thick, straight shaft. Fat is deposited along the spine, kidneys, gut mesentries and around the limbs. The least weasel has muscular anal glands under the tail, which measure 7 x 5 mm, and contain sulphurous volatiles, including thietanes and dithiacyclopentanes. The smell and chemical composition of these chemicals are distinct from those of the stoat.[17] The least weasel moves by jumping, the distance between the tracks of the fore and hind limbs being 18–35 cm.[18]

Dimensions vary geographically, to an extent rarely found among other mammals. Least weasels of the vulgaris group, for example, may outweigh the smaller races by almost four times. In some large subspecies, the male may be 1.5 times longer than the female. Variations in tail length are also variable, constituting from 13-30% of the length of the body. Average body length in males is 130–260 mm, while females average 114–204 mm. The tail measures 12–87 mm in males and 17–60 mm in females. Males weigh 36-250 grams, while females weigh 29.5-117 grams.[19]

The winter fur is dense, but short and closely fitting. In northern subspecies, the fur is soft and silky, but coarse in southern forms. The summer fur is very short, sparser and rougher. The upper parts in the summer fur are dark, but vary geographically from dark-tawny or dark-chocolate to light pale tawny or sandy. The lower parts, including the lower jaw and inner sides of the legs are white. The dividing line between the dark upper and light lower parts is straight, but sometimes forms an irregular line. In winter, the fur is pure white, and only exhibits black hairs in rare circumstances.[16]

Behaviour

Reproduction and development

The least weasel mates in April–July, with a 34-37 day gestation period. In the northern hemisphere, the average litter size consists of 6 kits, which reach sexual maturity in 3–4 months. Males may mate during their first year of life, though this is usually unsuccessful. They are fecund in February–October, though the early stages of spermatogenesis do occur throughout the winter months. Anestrus in females lasts from September-February.[20]

The female raises its kits alone, which are 1.5-4.5 grams in weight when born. Newborn kits are born pink, naked, blind and deaf, but gain a white coat of downy fur at the age of 4 days. At 10 days, the margin between the dark upper parts and light under parts becomes visible. The milk teeth erupt at 2–3 weeks of age, at which point they are weaned, though lactation can last 12 weeks. The eyes and ears open at 3–4 weeks of age, and by 8 weeks, killing behaviour is developed. The family breaks up after 9–12 weeks.[20]

Territorial and social behaviours

The least weasel has a typical Mustelid territorial pattern, consisting of exclusive male ranges encompassing multiple female ranges. The population density of each territory depends greatly on food supply and reproductive success, thus the social structure and population density of any given territory is unstable and flexible. Like the stoat, the male least weasel extends its range during spring or during food shortages. Its scent marking behaviour is similar to the stoat's; it uses faeces, urine and anal and dermal gland secretions, the latter two of which are deposited by anal dragging and body rubbing. The least weasel does not dig its own dens, but nest in the abandoned burrows of other species such as moles and rats.[22] The burrow entrance measures about 2.5 cm across and leads to the nest chamber located up to 15 cm below-ground. The nest chamber (which is used for sleeping, rearing kits and storing food) measures 10 cm in diametre, and is lined with straw and the skins of the weasel's prey.[23]

The least weasel has four basic vocalisations; a guttural hiss emitted when alarmed, which is interspersed with short screaming barks and shrieks when provoked. When defensive, it emits a shrill wail or squeal. During encounters between males and females or between a mother and kits, the least weasel emits a high-pitched trilling. The species' way of expressing aggression is similar to that of the stoat. Dominant weasels exhibit lunges and shrieks during aggressive encounters, while subdominant weasels will emit submissive squeals.[22]

Diet

The least weasel feeds predominantly on mouse-like rodents, including mice, hamsters, gerbils and others. It usually does not attack adult hamsters and rats. Frogs, fish, small birds and bird eggs are rarely eaten. It can deal with adult pikas and gerbils, but usually cannot overcome brown rats and sousliks. Exceptional cases are known of least weasels killing prey far larger than themselves, such as capercaillie, hazel hen and hares.[24] Rabbits are commonly taken, but are usually young specimens. Rabbits become an important food source during the spring, when small rodents are scarce and rabbit kits plentiful. Male least weasels take a higher proportion of rabbits than females, as well as an overall greater variety of prey. This is linked to the fact that being larger, and having vaster territorial ranges than females, males have more opportunities to hunt a greater diversity of prey.[25] The least weasel forages undercover, to avoid foxes and birds of prey. It is adapted for pursuing its prey down tunnels, though it may also bolt prey from their burrows and kill it in the open.[25] It kills small prey, such as voles, with a bite to the occipital region of the skull[24] or the neck, dislocating the cervical vertebrae. Large prey typically dies of blood loss or shock.[25] When food is abundant, only a small portion of the prey is eaten, usually the brain. The average daily food intake is 35 grams, which is equivalent to 30-35% of its body weight.[24]

Range

The least weasel has a circumboreal, Holarctic distribution, encompassing much of Europe and North Africa, Asia and northern North America, though it has been introduced in New Zealand, Malta, Crete, the Azore Islands and also Sao Tome off west Africa. It is found throughout Europe and on many islands, including the Azores, Britain (but not Ireland), and all major Mediterranean islands. It also occurs on Honshu and Hokkaido islands in Japan and on Kunashir, Iturup, and Sakhalin Islands in Russia.[1]

Predators and competitors

Least weasels driven from a mountain hare carcass by a stoat, as illustrated in Barrett-Hamilton's A History of British Mammals

Least weasels driven from a mountain hare carcass by a stoat, as illustrated in Barrett-Hamilton's A History of British Mammals

The least weasel is small enough to be preyed upon by a range of other predators.[26] Least weasel remains have been found in the excrement of red foxes, sables, steppe and forest polecat, stoats, eagle owls and buzzards.[27] The owls most efficient at capturing least weasels are barn, barred and great horned owls. Other birds of prey threatening to the least weasel include broad-winged and rough-legged buzzards. Some snake species may prey on the least weasel, including the black rat snake and copperhead.[23] Aside from its smaller size, the least weasel is more vulnerable to predation than the stoat because it lacks a black predator deflection mark on the tail.[26]

In areas where the least weasel is sympatric with the stoat, the two species compete with each other for rodent prey. The weasel manages to avoid overly competing with the stoat by living in more upland areas, and preying on smaller prey and being capable of entering smaller holes. The least weasel actively avoids encounters with stoats, though female weasels are less likely to stop foraging in the presence of stoats, likely because their smaller size allows them to quickly escape in holes.[28]

Diseases and parasites

Ectoparasites known to infest weasels include the louse Trichodectes mustelae and the mites Demodex and Psoregates mustela. The species may catch fleas from the nests and burrows of its prey. Flea species known to infest weasels include Ctenophthalmus bisoctodentatus and Palaeopsylla m. minor, which they get from moles, P. s. soricis, which they get from shrews, Nosopsyllus fasciatus, which they get from rodents and Dasypsyllus gallinulae which they get from birds.[26]

Helminths known to infest weasels include the trematode Alaria, the nematodes Capillaria, Filaroides and Trichinella and the cestode Taenia. Least weasels are commonly infected with Skrjabingylus nasicola, which burrows into their skulls and causes fits.[26]

In folklore and mythology

The Ancient Macedonians believed that to see a weasel was a good omen. In some districts of Macedon, women who suffered from headaches after having washed their heads in water drawn overnight would set the problem down to the fact that a weasel had previously used the water as a mirror, but they would refrain from mentioning the animal's name, for fear that it would destroy their clothes. Similarly, a popular superstition in southern Greece had it that the weasel had previously been a bride, who was transformed into a bitter animal which would destroy the wedding dresses of other brides out of jealousy.[29] According to Pliny the Elder, the weasel is the only animal capable of killing the basilisk;

To this dreadful monster the effluvium of the weasel is fatal, a thing that has been tried with success, for kings have often desired to see its body when killed; so true is it that it has pleased Nature that there should be nothing without its antidote. The animal is thrown into the hole of the basilisk, which is easily known from the soil around it being infected. The weasel destroys the basilisk by its odour, but dies itself in this struggle of nature against its own self.[30]

The Chippewa believed that the weasel could kill the dreaded wendigo giant by rushing up its anus.[31] In Inuit mythology, the weasel is credited with both great wisdom and courage, and whenever a mythical Inuit hero wished to accomplish a valorous task, he would generally change himself into a weasel.[32] According to Matthew Hopkins, a witch hunter general during the English Civil War, weasels were the familiars of witches.[33]

References

Notes

- ^ a b c Tikhonov, A., Cavallini, P., Maran, T., Kranz, A., Herrero, J., Giannatos, G., Stubbe, M., Conroy, J., Kryštufek, B., Abramov, A., Wozencraft, C., Reid, F. & McDonald, R. (2008). Mustela nivalis. In: IUCN 2008. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Downloaded on 21 March 2009. Database entry includes a brief justification of why this species is of least concern

- ^ Macdonald 1992, p. 208

- ^ Heptner & Sludskii 2002, p. 972

- ^ Kurtén 1968, pp. 102–103

- ^ Macdonald 1992, p. 205

- ^ Heptner & Sludskii 2002, pp. 975–978

- ^ Wozencraft, W. Christopher (16 November 2005). "Order Carnivora (pp. 532-628)". In Wilson, Don E., and Reeder, DeeAnn M., eds. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2 vols. (2142 pp.). ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494. http://www.bucknell.edu/msw3/browse.asp?id=14001438.

- ^ Heptner & Sludskii 2002, p. 982

- ^ Heptner & Sludskii 2002, p. 980

- ^ Heptner & Sludskii 2002, p. 981

- ^ Heptner & Sludskii 2002, p. 984

- ^ Heptner & Sludskii 2002, p. 978

- ^ Merriam 1896, pp. 14–15

- ^ Heptner & Sludskii 2002, p. 983

- ^ Heptner & Sludskii 2002, pp. 967–969

- ^ a b Heptner & Sludskii 2002, p. 969

- ^ a b Harris & Yalden 2008, p. 468

- ^ Heptner & Sludskii 2002, p. 991

- ^ Heptner & Sludskii 2002, pp. 970–972

- ^ a b Harris & Yalden 2008, p. 474

- ^ Harris & Yalden 2008, p. 154

- ^ a b Harris & Yalden 2008, pp. 471–472

- ^ a b Merritt & Matink 1987, p. 277

- ^ a b c Heptner & Sludskii 2002, pp. 987–988

- ^ a b c Harris & Yalden 2008, pp. 472–473

- ^ a b c d Harris & Yalden 2008, p. 475

- ^ Heptner & Sludskii 2002, p. 992

- ^ Harris & Yalden 2008, p. 469

- ^ Abbott, G. A. (1903), Macedonian Folklore, pp. 108-109, Cambridge University Press

- ^ Pliny the Elder, eds. John Bostock, H.T. Riley (translators) (1855). "The Natural History". http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/ptext?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.02.0137;query=chapter%3D%23358;layout=;loc=8.32. Retrieved 2009-06-10.

- ^ Barnouw, Victor (1979) Wisconsin Chippewa Myths & Tales: And Their Relation to Chippewa Life, pp. 53, University of Wisconsin Press, ISBN 0-299-07314-9

- ^ Dufresne, Frank (2005), Alaska's Animals and Fishes, pp. 109, Kessinger Publishing, ISBN 1-4179-8416-3

- ^ Summers, Montague (2005) Geography of Witchcraft, pp. 29, Kessinger Publishing, ISBN 0-7661-4536-0

Bibliography

- Coues, Elliott (1877). Fur-bearing Animals: A Monograph of North American Mustelidae. Government Printing Office. http://www.archive.org/details/furbearinganima00couegoog

- Harris, Stephen; Yalden, Derek (2008). Mammals of the British Isles. Mammal Society; 4th Revised edition edition. ISBN 0906282659

- Johnston, Harry Hamilton (1903), British mammals; an attempt to describe and illustrate the mammalian fauna of the British islands from the commencement of the Pleistocene period down to the present day, London, Hutchinson, http://www.archive.org/details/britishmammalsat00john

- Kurtén, Björn (1968). Pleistocene mammals of Europe. Weidenfeld and Nicolson

- Kurtén, Björn (1980). Pleistocene mammals of North America. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0231037333

- Heptner, V. G.; Sludskii, A. A. (2002). Mammals of the Soviet Union. Vol. II, part 1b, Carnivores (Mustelidae and Procyonidae). Washington, D.C. : Smithsonian Institution Libraries and National Science Foundation. ISBN 90-04-08876-8. http://www.archive.org/details/mammalsofsov212001gept

- Macdonald, David (1992). The Velvet Claw: A Natural History of the Carnivores. New York: Parkwest. ISBN 0563208449

- Merriam, Clinton Hart (1896), Synopsis of the weasels of North America, Washington : Govt. Print. Off., http://www.archive.org/details/synopsisofweasel00merriala

- Merritt, Joseph F.; Matinko, Ruth Anne (1987). Guide to the mammals of Pennsylvania. University of Pittsburgh Press. ISBN 0822953935

External links

Media related to Mustela nivalis at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Mustela nivalis at Wikimedia Commons  Data related to Mustela nivalis at WikispeciesCategories:

Data related to Mustela nivalis at WikispeciesCategories:- IUCN Red List least concern species

- Weasels

- Arctic land animals

- Fauna of Iran

- Fauna of the Arctic

- Mammals of the United Kingdom

- Mammals of Germany

- Mammals of Asia

- Mammals of Europe

- Mammals of North America

- Mammals of Canada

- Mammals of the United States

- Mammals of Great Britain

- Animals described in 1766

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.