- Banded Mongoose

-

Banded Mongoose

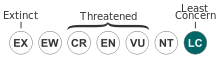

Lake Manyara, Tanzania Conservation status Scientific classification Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Class: Mammalia Order: Carnivora Family: Herpestidae Genus: Mungos Species: M. mungo Binomial name Mungos mungo

Gmelin, 1788

Banded Mongoose range The Banded Mongoose (Mungos mungo) is a mongoose commonly found in the central and eastern parts of Africa. It lives in savannas, open forests and grasslands and feeds primarily on beetles and millipedes. Mongooses use various types of dens for shelter including termite mounds. While most mongoose species live solitary lives, the banded mongoose live in colonies with a complex social structure.

Contents

Physical characteristics

The banded mongoose is a sturdy mongoose with a large head, small ears, short, muscular limbs and a long tail, almost as long as the rest of the body. Animals of wetter areas are larger and darker colored than animals of dryer regions. The abdominal part of the body is higher and rounder than the breast area. The rough fur is grayish brown, and there are several dark brown to black horizontal bars across the back. The limbs and snout are darker, while the underparts are lighter than the rest of the body. Banded mongooses have long strong claws that allow them to dig in the soil.

An adult animal can reach a length of 30 to 45 cm and a weight of 1.5 to 2.25 kg. The tail is 15 to 30 cm long.

Range and ecology

The banded mongoose is found in a large part of East, Southeast and South-Central Africa. There are also populations in the northern savannas of West Africa. The banded mongoose lives in savannas, open forests and grassland, especially near water, but also in dry, thorny bushland but not deserts. The species uses various types of dens for shelter, most commonly termite mounds.[2] They will also live in rock shelters, thickets, gullies, and warrens under bushes. Mongooses prefer multi-entranced termitaria with open thicket, averaging 4 m from the nearest shelter, located in semi-closed woodland.[3] In contrast to the den of the dwarf mongoose, banded mongoose dens are less dependent on vegetation cover and have more entrances.[3] Banded mongooses live in larger groups than dwarf mongooses and this more entrances means more members have access to the den and ventilation.[3] The development of agriculture in the continent has had a positive influence on the number of banded mongooses. The crops of the farmland serve as an extra food source.

Food and foraging

Banded mongoose feed primarily on insects, myriapods, small reptiles, and birds. Millipedes and beetles made of most of their diet.[2] Ants, crickets, termites, grasshoppers, caterpillars and earwigs are also important parts of their diet.[4][5] Other prey items of the mongoose includes frogs, lizards, small snakes, ground bird and the eggs of both birds and reptiles.[4] On some occasions, mongooses will drink water from rain pools and lake shores.[4]

Banded mongoose groups forage as a unit while each individual finds its own food.[4] They embark on foraging trips every morning for several hours and then retire to shade to rest. They will often have a second foraging trip late in the afternoon. Mongooses use their sense of smell to locate their prey and dig them out with their long claws, both in hole in the ground and holes in trees. Mongoose will also frequent near the dung of large herbivores since they attract millipedes and beetles. [4] Low grunts are produced every few seconds so each mongoose can maintain contact with each other. Mongooses do not share food and will defend food and potential food from each other. When hunting prey that produce noxious secretions, like frogs and millipedes, mongooses will roll them around the ground before eating them. With eggs and hard-shelled prey, like dung beetles, mongoose will clasp the food item between its front paws and throws it behind its hind legs and onto a hard surface like a rock.[6]

Social behaviour

Banded mongooses live in mixed-sex groups of 7–40 individuals (average around 20).[7] Groups sleep together at night in underground dens, often abandoned termite mounds, and change dens frequently (every 2–3 days). When no refuge is available and hard-pressed by predators such as wild dogs, the group will form a compact arrangement in which they lie on each other with heads facing outwards and upwards.

There is generally no strict hierarchy in mongoose groups. In addition, aggression within groups tends to be low. Sometimes, mongoose may squabble over a food item, however the finder of the food is usually the winner. Most aggression and hierarchical behavior occurs between males when females are in oestrus. Female are usually not aggressive but have an age-based hierarchy in which older females enter estrous earlier and have larger litters.[7] Adult females are forcibly evicted from the group when their numbers grow large. Females are evicted by older females and sometimes males. When these dispersing females encounter neighbouring groups they may be joined by groups of subordinate males to start a new group.[8]

Relations between groups are highly aggressive and mongooses are sometimes killed and injured during intergroup encounters. Nevertheless, breeding females will often mate with males from a rival group in the midst of a fight.[9] Mongooses use scent markings for territorial demarcation and defensive but may also be used in communicating within social groups.[10] In the society of the banded mongoose there is a clear separation between mating rivals and territorial rivals. Individuals within groups are rivals for mates while those from neighboring groups are competitors for food and resources.[10]

Reproduction

The species is unusual among cooperative vertebrates because most females reproduce in each breeding attempt.[7] All adult females in a group enter oestrus around 10 days after giving birth, and are guarded and mated by 1–3 dominant males.[7] The dominant males monitor the females and aggressively defend them from subordinates. While these males do most of the mating, the females often try to escape from them and mate with other males in the group. Typically a dominant male will guard the same female for 2–3 days before moving on to another one.[7] A guarding male is aggressive towards any male that approaches the female he is guarding. In these situations, aggression is displayed in the form of snaps, lunges and pounces.[7] A guarding male and this female are often trailed by one or two "sneaky" males that wait for an opportunity to mate with the female. These males are the most common targets of the guarding male's aggression. Matings by non-guarding males tend to be more hidden and surreptitious.[7]

Gestation is 60–70 days. Around 70% of adult females in the group carry to term, and give birth together in an underground den. In most breeding attempts, all females give birth on exactly the same day.[7][11] Each female gives birth to 2–5 pups; average litter size is four. Pups are kept underground for the first four weeks of life, during which time they are guarded at the den by 1–3 babysitters while the rest of the group goes off to forage.[12] After four weeks, the pups join the group on foraging trips. Each pup is cared for by a single adult "escort" who helps the pup to find food and protects it from danger.[13] Pups become nutritionally independent at three months of age.

Interspecies relations

In some locations (e.g., Kenya) banded mongooses have been found in close relationship with baboons.[citation needed] They forage together and probably enjoy greater security as a large group because of more eyes on the lookout for predators. The mongooses are handled by baboons of all ages and show no fear of such contact.

Banded mongooses have been observed removing ticks and other parasites from warthogs in Kenya[14] and Uganda.[15] The mongooses get food, while the warthogs get cleaned.

Status and abundance

Banded Mongooses are present in numerous protected areas across their wide range on the African continent.[1] In the Serengeti of Tanzania, mongooses life at a density of around 3 animals per km2.[16] In southern KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, mongoose numbers are at a similar density at 2.4 km2.[17] Queen Elizabeth National Park has a much higher population density of mongooses at 18/km2.[18] Overall the banded mongoose tends to be more abundant in the eastern and south-eastern areas of its range than in more western areas.

References

- ^ a b Hoffmann, M. (2008). Mungos mungo. In: IUCN 2008. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Downloaded on 22 March 2009. Database entry includes a brief justification of why this species is of least concern.

- ^ a b Neal, E. (1970). "The banded mongoose, Mungos mungo Gmelin." East African Wildlife Journal 8: 63-71.

- ^ a b c Hiscocks, K., Perrin, M. R. (1991). "Den selection and use by dwarf mongooses and banded mongooses in South Africa." South African Journal of Wildlife Research 21(4): 119-122.

- ^ a b c d e Rood, J. P. (1975). "Population dynamics and food habits of the banded mongoose." East African Journal of Wildlife 13: 89-111.

- ^ Smithers, R.H.N (1971) The mammals of Botswana, National Museums of Rhodesia. 4:1-340.

- ^ Simpson, C.D. (1964) "Notes on the banded mongoose, Mungos mungo (Gmelin)". Arnoldia, Rhodesia 1(19):1-8

- ^ a b c d e f g h CANT, M.A. (2000) Social control of reproduction in banded mongooses. Anim. Behav. 59:147-158

- ^ CANT, M.A., OTALI, E. & MWANGUHYA, F. (2001). Eviction and dispersal in cooperatively breeding banded mongooses. J. Zool. 254:155-162

- ^ CANT, M.A., OTALI, E. & MWANGUHYA, F. (2002). Fighting and mating between groups in cooperatively breeding banded mongooses. Ethology 108:541-555

- ^ a b Jordan, N.R., Mwanguhya, F., Kyabulima, S., Ruedi, P., and Cant, M.A. (2010) "Scent marking within and between groups in banded mongooses". Journal of Zoology 280:72-83.

- ^ GILCHRIST, J.S. (2006). Female eviction, abortion and infanticide in the banded mongoose (Mungos mungo). Behav. Ecol. 17:664-669

- ^ CANT, M.A. (2003) Patterns of helping effort in cooperatively breeding banded mongooses. J. Zool. 259:115-119

- ^ GILCHRIST, J.S. (2004). Pup escorting in the communal breeding banded mongoose: behavior benefits and maintenance. Behav. Ecol. 15:952-960

- ^ Warthog at Wildwatch.com

- ^ Banded Brothers episode 1 at bbc.co.uk

- ^ Waser, PM, LF Elliott, and SR Creel. 1995. "Habitat variation and viverrid demography". In ARE Sinclair and P Arcese (eds.) Serengeti II: Dynamics, Management and Conservation of an Ecosystem, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp. 421-447.

- ^ Maddock. A. H. (1988). "Resource partitioning in a viverrid assemblage". PhD thesis, University of Natal. Pietermaritzburg

- ^ Gilchrist, Jason and Otali, E (2002) "The effects of refuse-feeding on home-range use, group size, and intergroup encounters in the banded mongoose". Canadian Journal of Zoology, 80 (10). pp. 1795-1802.

External links

- Banded Mongoose Research Project

- Species profile bandedmongoose.org

Categories:- IUCN Red List least concern species

- Mongooses

- Carnivorans of Africa

- Fauna of West Africa

- Fauna of the Sahara

- Mammals of Sudan

- Mammals of Ethiopia

- Mammals of the Democratic Republic of the Congo

- Fauna of East Africa

- Mammals of Kenya

- Mammals of Tanzania

- Mammals of Angola

- Mammals of Namibia

- Mammals of Zambia

- Mammals of South Africa

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.