- Mustelidae

-

Mustelids

Temporal range: Early Miocene–RecentLongtail Weasel Scientific classification Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Class: Mammalia Order: Carnivora Suborder: Caniformia Superfamily: Musteloidea Family: Mustelidae

G. Fischer de Waldheim, 1817Subfamilies Lutrinae

Melinae

Mellivorinae

Taxideinae

MustelinaeMustelidae (from Latin mustela, weasel), commonly referred to as the weasel family, are a family of carnivorous mammals. Mustelids are diverse and the largest family in the order Carnivora, at least partly because in the past it has been a catch-all category for many early or poorly differentiated taxa.[citation needed] The internal classification seems to be still quite unsettled, with rival proposals containing between two and eight subfamilies. One study published in 2008 questions the long accepted Mustelinae subfamily, and suggests that Mustelidae consists of four major clades and three much smaller lineages.[citation needed]

Contents

Variety

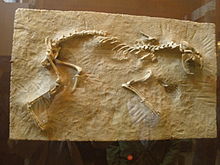

Sthenictis sp. (American Museum of Natural History)

The Mustelidae in general are phylogenetically relatively primitive and so were difficult to classify until genetic evidence started to become available. The increasing availability of such evidence may well result in some members of the family being moved to their own separate families, as has already happened with the skunks, previously considered to be members of the mustelid family.

Mustelids vary greatly in size and behavior. The least weasel is not much larger than a mouse. At the other end of the scale, giant otter can measure up to 2.4 metres (7.9 ft) in total length and sea otters can exceed 45 kilograms (99 lb). The wolverine can crush bones as thick as the femur of a moose to get at the marrow, and has been seen attempting to drive bears away from its kill. The sea otter uses rocks to break open shellfish to eat. The marten is largely arboreal, while the badger digs extensive networks of tunnels, called setts. Some mustelids have been domesticated. The ferret and the tayra are kept as pets (although the tayra requires a Dangerous Wild Animals licence in the UK), or as working animals for hunting or vermin control. Others have been important in the fur trade. The mink is often raised for its fur.

As well as one of the most species-rich families in the order Carnivora, mustelidae is one of the oldest. Mustelid-like forms first appeared about 40 million years ago, roughly coinciding with the appearance of rodents. The direct ancestors of the modern mustelids first appeared about 15 million years ago.

Characteristics

Within a large range of variation, the mustelids exhibit some common characteristics. They are typically small animals with short legs, short round ears, and thick fur. Most mustelids are solitary, nocturnal animals, and are active year-round.[1]

Mustelids, with the exception of the sea otter,[2] have anal scent glands that produce a strong-smelling secretion the animals use for sexual signaling and for marking territory.

Most mustelid reproduction involves embryonic diapause. The embryo does not immediately implant in the uterus, but remains dormant for a period of time. No development takes place as long as the embryo remains unattached to the uterine lining. As a result, the normal gestation period is extended, sometimes up to a year. This allows the young to be born under more favorable environmental conditions. Reproduction has a large energy cost and it is to a female's benefit to have available food and mild weather. The young are more likely to survive if birth occurs after previous offspring have been weaned.

Mustelids are predominantly carnivorous, although some will sometimes eat vegetable matter. While not all mustelids share an identical dentition, they all possess teeth adapted for eating flesh, including the presence of shearing carnassials. Although there is variation between species, the most common dental formula is:[1]

Dentition 3.1.3.1 3.1.3.2 Ecology

Several members of the family are aquatic to varying degrees, ranging from the semi-aquatic mink, the river otters, and the highly aquatic sea otter. The sea otter is one of the few non-primate mammals known to use a tool while foraging. It uses "anvil" stones to crack open the shellfish that form a significant part of its diet. It is a "keystone species", keeping its prey populations in balance so some do not outcompete the others and they do not destroy the kelp in which they live.

The black-footed ferret is entirely dependent on another keystone species, the prairie dog. A family of four ferrets will eat 250 prairie dogs in a year. The ferrets require a prairie dog colony of 500 acres (2.0 km2) to maintain a stable population to support their predation.

The Mongoose and the meerkat bear a striking resemblance to many mustelids but belong to a distinctly different suborder - the Feliformia (all those carnivores sharing more recent origins with the Felidae) and not the Caniformia (those sharing more recent origins with the Canidae). Because the mongoose and the mustelids occupy similar ecological niches, convergent evolution has led to some similarity in form and behavior.[citation needed]

Human uses

Several mustelids, including the mink, the sable (a type of marten) and the stoat (ermine), boast exquisite and valuable furs and have been accordingly hunted since prehistoric times. Since the early middle-ages the trade in furs was of great economic importance for northern and eastern European nations with large native populations of fur-bearing mustelids, and was a major economic impetus behind Russian expansion into Siberia and French and English expansion in North America. In recent centuries fur farming, notably of mink, has also become widespread and provides the majority of the fur brought to market.

One species, the Sea Mink (Neovison macrodon) of New England and Canada, was driven to extinction by fur trappers. Its appearance and habits are almost unknown today because no complete specimens can be found and no systematic contemporary studies were conducted.

The sea otter, which has the densest fur of any animal,[3] narrowly escaped the fate of the sea mink. The discovery of large populations in the North Pacific was the major economic driving force behind Russian expansion into Kamchatka, the Aleutian islands and Alaska, as well as a cause for conflict with Japan and foreign hunters in the Kuril Islands. Together with widespread hunting in California and British Columbia, the species was brought to the brink of extinction until an international moratorium came into effect in 1911.

Today some mustelids are threatened for other reasons. Sea otters are vulnerable to oil spills and the indirect effects of overfishing; the black-footed ferret, a relative of the European polecat, suffers from the loss of American prairie; and wolverine populations are slowly declining because of habitat destruction and persecution. The rare European mink Mustela lutreola is one the most endangered mustelid species.[4]

One mustelid, the domestic ferret (Mustela putorius furo), has been domesticated since ancient times, originally for hunting rabbits and pest control.

Systematics

The number of subfamilies proposed for Mustelidae ranges from two to eight. Here is the eightfold proposal.[citation needed]

Mustelidae Lutrinae

Mustela, Neovison (Subfamily Mustelinae)

Galictis, Vormela, Ictonyx, Poecilogale (Subfamily Galictinae)

Melogale (Subfamily Helictidinae)

Eira, Gulo, Martes (Subfamily Martinae)

Arctonyx, Meles (Subfamily Melinae)

Mellivora (Subfamily Mellivorinae)

Taxidea (Subfamily Taxideinae)

One reference work suggests that Mustelidae should be divided into just two extant subfamilies, denoted Lutrinae and Mustelinae.[5]

Koepfli et al. (2008) counters that Mustelinae is not a valid taxon, proposing instead that the Mustelidae are divided into four major clades and three, much smaller, lineages. The early mustelids appear to have undergone two rapid bursts of diversification in Eurasia, with the resulting species only spreading to other continents later.[6]

Examination of the mitochondrial DNA[7] suggests that the Taxidiinae diverged first, followed by Melinae. Lutrinae and Mustelinae are sister clades. The position of the Helictidinae is unclear because the mitochondrial evidence suggests they are related to Lutrinae-Mustelinae clade but the intron data suggests a relationship to Martinae.

Extant species

According to the theory mentioned above proposing two subfamilies, 57 species are classified as follows.

FAMILY MUSTELIDAE (57 species in 22 genera)

- Subfamily Lutrinae (Otters)

- Genus Aonyx

- African Clawless Otter, Aonyx capensis

- Oriental Small-clawed Otter, Aonyx cinerea

- Genus Enhydra

- Sea Otter, Enhydra lutris

- Genus Lontra (American River Otters and Marine Otters)

- Northern River Otter, Lontra canadensis

- Southern River Otter, Lontra provocax

- Neotropical River Otter, Lontra longicaudis

- Marine Otter, Lontra felina

- Genus Lutra

- Eurasian Otter, Lutra lutra

- Hairy-nosed Otter, Lutra sumatrana

- Genus Hydrictis

- Spotted-necked Otter, Hydrictis maculicollis

- Genus Lutrogale

- Smooth-coated Otter, Lutrogale perspicillata

- Genus Pteronura

- Giant Otter, Pteronura brasiliensis

- Genus Aonyx

- Subfamily Mustelinae

- Genus Arctonyx

- Hog Badger, Arctonyx collaris

- Genus Eira

- Tayra, Eira barbara

- Genus Galictis (Grisón)

- Greater Grison, Galictis vittata

- Lesser Grison, Galictis cuja

- Genus Gulo

- Wolverine, Gulo gulo

- Genus Ictonyx

- Striped Polecat, Ictonyx striatus

- Saharan Striped Polecat, Ictonyx libycus

- Genus Lyncodon

- Patagonian Weasel, Lyncodon patagonicus

- Genus Martes (Sable, Fishers and Martens)

- American Marten, Martes americana

- Yellow-throated Marten, Martes flavigula

- Beech Marten, Martes foina

- Nilgiri Marten, Martes gwatkinsii

- Pine Marten, Martes martes

- Japanese Marten, Martes melampus

- Fisher, Martes pennanti

- Sable, Martes zibellina

- Genus Meles

- Japanese Badger, Meles anakuma

- Asian Badger, Meles leucurus

- European Badger, Meles meles

- Genus Mellivora

- Honey Badger, Mellivora capensis

- Genus Melogale (Ferret Badgers)

- Bornean Ferret-badger, Melogale everetti

- Chinese Ferret-badger, Melogale moschata

- Javan Ferret-badger, Melogale orientalis

- Burmese Ferret-badger, Melogale personata

- Genus Mustela (Weasels, Ferrets, European Mink and Stoats)

- Amazon Weasel, Mustela africana

- Mountain Weasel, Mustela altaica

- Ermine (Stoat), Mustela erminea

- Steppe Polecat, Mustela eversmannii

- Colombian Weasel, Mustela felipei

- Long-tailed Weasel, Mustela frenata

- Japanese Weasel, Mustela itatsi

- Yellow-bellied Weasel, Mustela kathiah

- European Mink, Mustela lutreola

- Indonesian Mountain Weasel, Mustela lutreolina

- Black-footed Ferret, Mustela nigripes

- Least Weasel, Mustela nivalis

- Malayan Weasel, Mustela nudipes

- European Polecat, Mustela putorius

- Domesticated Ferret, Mustela putorius furo

- Siberian Weasel, Mustela sibirica

- Back-striped Weasel, Mustela strigidorsa

- Egyptian Weasel, Mustela subpalmata

- Genus Neovison

- American Mink, Neovison vison

- Sea Mink, Neovison macrodon (19th century †)

- Genus Poecilogale

- African Striped Weasel, Poecilogale albinucha

- Genus Taxidea

- American Badger, Taxidea taxus

- Genus Vormela

- Marbled Polecat, Vormela peregusna

- Genus Arctonyx

Fossil Mustelids

Extinct genera of the Mustelidae family include:

- Brachypsalis

- Chamitataxus

- Cyrnaonyx

- Ekorus

- Megalictis

- Oligobunis

- Potamotherium

- Sthenictis

Notes

- ^ a b King, Carolyn (1984). Macdonald, D.. ed. The Encyclopedia of Mammals. New York: Facts on File. pp. 108–109. ISBN 0-87196-871-1.

- ^ Kenyon, Karl W. (1969). The Sea Otter in the Eastern Pacific Ocean. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife.

- ^ Perrin, William F., Wursig, Bernd, and Thewissen, J.G.M. Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals, 2nd ed. Academic Press; 2 edition (December 8, 2008). Page 529. [1]

- ^ Thierry Lodé, J. P. Cornier & D. Le Jacques 2001. Decline in endangered species as an indication of anthropic pressures: the case of European mink Mustela lutreola western population. Environmental management 28: 221-227.

- ^ "Wilson & Reeder's Mammal Species of the World, Third Edition". http://www.bucknell.edu/msw3/browse.asp?id=14001075. Retrieved 2008-07-31.

- ^ Koepfli, Klaus-Peter; Deere, K.A.; Slater, G.J.; Begg, C.; Begg, K.; Grassman, L.; Lucherini, M.; Veron, G. et al. (February 2008). "Multigene phylogeny of the Mustelidae: Resolving relationships, tempo and biogeographic history of a mammalian adaptive radiation". BMC Biology 6: 10. doi:10.1186/1741-7007-6-10. PMC 2276185. PMID 18275614. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1741-7007/6/10.

- ^ Yu L, Peng D, Liu J, Luan P, Liang L, Lee H, Lee M, Ryder OA, Zhang Y (2011) On the phylogeny of Mustelidae subfamilies: analysis of seventeen nuclear non-coding loci and mitochondrial complete genomes. BMC Evol Biol 10;11(1):92

Further reading

- Whitaker, John O. (1980-10-12). The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Mammals. Alfred A. Knopf. p. 745. ISBN 0394507622.

Categories:- Carnivorans

- Mustelidae

- Subfamily Lutrinae (Otters)

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.