- South American Sea Lion

-

- Otaria redirects here. For the continent in Magic: The Gathering, see Otaria.

South American sea lion

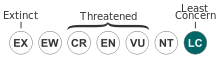

Conservation status Scientific classification Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Class: Mammalia Order: Carnivora Suborder: Pinnipedia Family: Otariidae Subfamily: Otariinae Genus: Otaria

Péron, 1816Species: O. flavescens Binomial name Otaria flavescens

(Shaw, 1800)

South American Sea Lion range The South American sea lion (Otaria flavescens, formerly Otaria byronia), also called the southern sea lion and the Patagonian sea lion, is a sea lion found on the Chilean, Peruvian, Uruguayan, Argentine and Southern Brazilian coasts. It is the only member of the genus Otaria. Its scientific name was subject to controversy, with some taxonomists referring to it as Otaria flavescens and others referring to it as Otaria byronia. The former eventually won out.[2] Locally, it is known by several names though the most common ones are lobo marino (sea wolf) and león marino (sea lion).

Contents

Physical description

The South American sea lion is perhaps the archetypal sea lion in appearance. Males have a very large head with a well-developed mane, making them the most lionesque of the eared seals. They are twice the weight of females.[3] Both males and females are orange or brown coloured with upturned snouts. Pups are born greyish orange ventrally and black dorsally and moult into a more chocolate colour.

The South American sea lion's size and weight can vary considerably. Adult males can grow over 2.73 m (9 ft) and weigh up to 350 kg (770 lb).[4] Adult females grow up to 1.8–2 m (6–7 ft) and weigh about half the weight of the males, around 150 kg (330 lb). These sea lions are the most sexually dimorphic of the five sea lion species.[5]

Ecology

As its name suggests, the South American sea lion is found along the coasts and offshore islands of South America. It ranges from Peru south to Chile in the Pacific and then north to southern Brazil in the Atlantic.[6] It generally breeds in the southern part of its range and travels north in winter and spring.[6] Notable breeding colonies include Lobos Island, Uruguay; Peninsula Valdes, Argentina; Beagle Channel and the Falkland Islands. Some individuals wander as far north as southern Ecuador, although apparently they never bred there.

South American sea lions prefer to breed on beaches made of sand, but will breed on gravel, rocky or pebble beaches, as well.[6] They can also be seen on flat rocky cliffs with tidepools.[6] Sea lion colonies are more scattered on rocky beaches than sand, gravel or pebble beaches.[6] The colonies make spaces between each individual when it is warm and sunny.[6] They can also be found in marinas and wharves but do not breed there.

South American sea lions feed on a variety of fish, including Argentine hake and anchovies.[6] They also eat cephalopods, such as shortfin squid, Patagonian squid and octopus.[6] They have even been observed preying on penguins, pelicans and young South American fur seals. South American sea lions normally hunt in shallow waters less than five miles from shore. They often forage at the ocean floor for slow moving prey, but they will also hunt schooling prey in groups. When captured, the prey is shaken violently and torn apart. South American sea lions have been recorded to take advantage of the hunting efforts of dusky dolphins, feeding on the fish they herd together.[7] The sea lions themselves are preyed on by orcas and sharks.

Social behavior and reproduction

Mating occurs between August and December, and the pups are born between December and February. Males arrive first to establish and defend territories, but then switch to defending females when they arrive.[8] Males will fight and use threat displays towards neighbours and intruders to protect both their territories and females.[8] A male will forcefully keep pre-estrous females near him.[8] On rocky beaches, males defend small territories where females aggregate and herd them.[6] On cobble or sandy beaches, which are longer and broader, males stay along the surf line and try to herd females going to sea to cool down or forage.[6] The number of actual fights between males depends on the number of females in heat.[8] The earlier a male arrives at the site the longer his tenure will be and the more copulations he will achieve.[8] Males are usually able to keep around three females in their harem, but some have as many as 18.[8]

During the breeding season, males that fail to secure territories and harems, most often sub-adults, will cause group raids in an attempt to change the status-quo and gain access to the females.[9] Group raids are more common on sandy beaches than rocky ones.[9] These raids cause chaos in the breeding harems, often splitting mothers from their young. The resident males will try to fight off the the raiders and keep all the females in their territorial boundaries. Raiders are often unsuccessful in securing a female, however some are able to capture some females or even depose of a resident male and remain in the breeding area with one or more females.[9] Sometimes an invading male will abduct pups, possibly as an attempt to control the females.[9] They also take pups as substitutes for mature females.[10] Sub-adults will herd their captured pups and prevent them from escaping, much like what adult males do to females.[10] A pup may be mounted by its abductor but intromission does not occur.[10] While abducting pups does not give males immediate reproductive benefits, these males may gain experience in controlling females.[10] Pups are sometimes severely injured or killed during abductions.[9][10]

Sea lion mothers remain with their newborn pups for nearly a week before making routine of taking three day foraging trips and coming back to nurse the pups.[6][8] They will act aggressively to other females who come close to their pups, as well as alien pups who try to get milk from them.[11] Pups first enter the water at about four weeks and are weaned at about 12 months. This is normally when the mother gives birth to a new pup. Pups gradually spent more time in the nearshore surf and develop swimming skills.[6]

South American sea lions are observed to make various vocalizations and calls which differs between sexes and ages.[12] Adult males will make high-pitched calls during aggressive interactions,[12] barks when establishing territories,[12] growls when interacting with females,[12] and exhalations which are made after agonistic encounters.[12] Females who have pups make what is called a mother primary call when interacting with their pups,[12] and grunts during aggressive encounters with other females.[12] Pups make what are called pup primary calls.[12] Some of those vocalizations and acoustic features may support individuality.[12]

Human interactions

The Moche people of ancient Peru worshipped the sea and its animals. They often depicted South American sea lions in their art.[13] A statue of this species is a symbol of Mar del Plata.

Indigenous peoples of South America have hunted South American sea lions for thousands of years and at least 16th century European have hunted them food, oil and hides.[14] The hunting has since gone down and the species is no longer threatened. The species is protected in most of its range.[1] Numerous reserves and protected areas at rookeries and haul-out sites, especially in Argentina, have been established and have given the sea lion much protection.[1] Despite this, enforcement of protection regulations is weak in most of the animal's range, especially in the most isolated areas and at sea.[1]

The population estimate is 265,000 animals. They are increasing in Argentina, but are declining in Chile and Uruguay.[1] Many sea lions of the Peruvian population died in the 1997/1998 el Niño.[1] They still are killed due to the sea lions' habits of stealing fish and damaging fishing nets.[1] Sea lions in the port of Mar del Plata have been found with toxic chemicals and heavy metals in their systems.[15] The overall population of sea lions is considered stable.

See also

- Pincoy

References

- ^ a b c d e f g Campagna, C. (2008). Otaria flavescens. In: IUCN 2008. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Downloaded on 30 January 2009.

- ^ Rodriguez, D., R. Bastida. 1993. The southern sea lion, Otaria byronia or Otaria flavescens?. Marine Mammal Science, 9(4): 372-381.

- ^ Kindersley, Dorling (2001,2005). Animal. New York City: DK Publishing. ISBN 0-7894-7764-5.

- ^ http://www.theanimalfiles.com/mammals/seals_sea_lions/south_american_sea_lion.html

- ^ http://www.sealionsearch-rescue.com/facts.html

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Randall R. Reeves, Brent S. Stewart, Phillip J. Clapham and James A. Powell (2002). National Audubon Society Guide to Marine Mammals of the World. Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. ISBN 0375411410.

- ^ Würsig, B. and Würsig, M. 1980. "Behavior and ecology of the dusky dolphin, Lagenorhynchus obscurus, in the South Atlantic". Fishery Bulletin 77: 871-890.

- ^ a b c d e f g Campagna, C., B. Le Boeuf. 1988. "Reproductive behavior of southern sea lions". Behaviour, 104(3-4): 233-261.

- ^ a b c d e Campagna, C., B. Le Boeuf, H. Capposso. 1988. "Group raids: a mating strategy of male southern sea lions". Behaviour, 105(3-4): 224-249.

- ^ a b c d e Campagna, C., B. Le Boeuf, H. Cappozzo. 1988. "Pup abduction and infanticide in southern sea lions". Behaviour, 107(1-2): 44-60.

- ^ Esteban Fernández-Juricic and Marcelo H. Cassini. "Intra-sexual female agonistic behaviour of the South American sea lion (Otaria flavescens) in two colonies with different breeding substrates". Acta ethologica, Volume 10, Number 1, 23-28, DOI: 10.1007/s10211-006-0024-4. (2007)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Esteban Fernández-Juricic, Claudio Campagna, Víctor Enriquez and Charles Leo Ortiz "Vocal Communication and Individual Variation in Breeding South American Sea Lions". Behaviour, Vol. 136, No. 4 (May, 1999), pp. 495-517

- ^ Berrin, Katherine & Larco Museum. The Spirit of Ancient Peru:Treasures from the Museo Arqueológico Rafael Larco Herrera. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1997.

- ^ Rodriguez, D. and Bastida, R. 1998. "Four hundred years in the history of pinniped colonies around Mar del Plata, Argentina". Aquatic Conservation of Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems 8: 721-735.

- ^ Sepulveda, M., M. Alvarado-Rybak, C. Verdugo, E. Quiroz, C. Valencia, C. Munoz-Zanzi, R. Tamayo. Pathogens and heavy metals in Southern sea lions (Otaria flavescens) in Valdivia city, Chile. Arch Med Vet. In review.

Categories:- IUCN Red List least concern species

- Eared seals

- Mammals of South America

- Mammals of Chile

- Mammals of Argentina

- Mammals of Peru

- Fauna of Uruguay

- Western South American coastal fauna

- Southeastern South American coastal fauna

- Megafauna of South America

- Monotypic mammal genera

- Animals described in 1800

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.