- History of Portugal (1415–1578)

-

- For additional context, see History of Portugal and Portuguese Empire.

History of Portugal

This article is part of a seriesPrehistoric Iberia Early history Lusitania and Gallaecia 711–1139 Kingdom of Portugal 1139–1279 1279–1415 1415–1578 1578–1777 1777–1834 1834–1910 Portuguese Republic 1910–1926 1926–1933 1933–1974 1974–present Topic Colonial history Art history Economic history History of the Azores History of Madeira Language history Military history Music history Women's history

Portugal Portal

During the history of Portugal between 1415 and 1578, Portugal discovered an eastern route to India that rounded the Cape of Good Hope, discovered Brazil, established trading routes throughout most of southern Asia, colonized selected areas of Africa, and sent the first direct European maritime trade and diplomatic missions to China and Japan.

Contents

Reasons for exploration

Portugal's long shoreline, with its many harbours and rivers flowing westward to the Atlantic ocean was the ideal environment to raise generations of adventurous seamen. As a seafaring people in the south-westernmost region of Europe, the Portuguese became natural leaders of exploration during the Middle Ages. Faced with the options of either accessing other European markets by sea (by exploiting its seafaring prowess) or by land (and facing the task of crossing Castile and Aragon territory) it is not surprising that goods were sent via the sea to England, Flanders, Italy and the Hanseatic league towns.

Having fought to achieve and to retain independence, the nation's leadership had also a desire for fresh conquests. Added to this was a long struggle to expel the Moors that was religiously sanctioned and influenced by foreign crusaders with a desire for martial fame. Making war on Islam seemed to the Portuguese both their natural destiny and their duty as Christians.

One important reason was the need to overcome the expensive eastern trade routes, dominated first by the republics of Venice and Genoa in the Mediterranean, and then controlled by the Ottoman Empire after the conquest of Constantinople in 1453, barring European access, and going through North Africa and the historically important combined-land-sea routes via the Red Sea. Both spice and silk were big businesses of the day, and arguably, spices which were used as medicine drugs and preservatives was something of a necessity—at least to those Europeans of better than modest means.

The Portuguese economy had benefited from its connections with neighbouring Muslim states. A money economy was well enough established for 15th century workers in the countryside as well as in the towns to be paid in currency. The agriculture of the countryside had diversified to the point where grain was imported from Morocco (a symptom of an economy dependent upon Portugal's), while specialised crops occupied former grain-growing areas: vineyards, olives, or the sugar factories of the Algarve, later to be reproduced in Brazil (Braudel 1985). Most of all, the Aviz dynasty that had come to power in 1385 marked the semi-eclipse of the conservative land-oriented aristocracy (See The Consolidation of the Monarchy in Portugal.) A constant exchange of cultural ideals made Portugal a centre of knowledge and technological development. Due to these connections with Islamic kingdoms, many mathematicians and experts in naval technology appeared in Portugal. The Portuguese government impelled this even further by taking full advantage of this and by creating several important research centres in Portugal, where Portuguese and foreign experts made several breakthroughs in the fields of mathematics, cartography and naval technology. Sagres and Lagos in the Algarve become famous as such places.

Portuguese nautical science

The successive expeditions and experience of the pilots led to a fairly rapid evolution of Portuguese nautical science, creating an elite of astronomers, navigators, mathematicians and cartographers, among them stood Pedro Nunes with studies on how to determine the latitudes by the stars and João de Castro.

Ships

Until the 15th century, the Portuguese were limited to coastal cabotage navigation using barques and barinels (ancient cargo vessels used in the Mediterranean). These boats were small and fragile, with only one mast with a fixed quadrangular sail and did not have the capabilities to overcome the navigational difficulties associated with Southward oceanic exploration, as the strong winds, shoals and strong ocean currents easily overwhelmed their abilities. They are associated with the earliest discoveries, such as the Madeira Islands, the Azores, the Canaries, and to the early exploration of the north west African coast as far south as Arguim in the current Mauritania.

The ship that truly launched the first phase of the Portuguese discoveries along the African coast was the caravel, a development based on existing fishing boats. They were agile and easier to navigate, with a tonnage of 50 to 160 tons and 1 to 3 masts, with lateen triangular sails allowing luffing. The caravel benefited from a greater capacity to tack. The limited capacity for cargo and crew were their main drawbacks, but have not hindered its success. Limited crew and cargo space was acceptable, initially, because as exploratory ships, their "cargo" was what was in the explorer's feedback of a new territory, which only took up the space of one person.[1] Among the famous caravels are Berrio and Caravela Annunciation.

With the start of long oceanic sailing also large ships developed. "Nau" was the Portuguese archaic synonym for any large ship, primarily merchant ships. Due to the piracy that plagued the coasts, they began to be used in the navy and were provided with canon windows, which led to the classification of "naus" according to the power of its artillery. They were also adapted to the increasing maritime trade: from 200 tons capacity in the 15th century to 500, they become impressive in the 16th century, having usually two decks, stern castles fore and aft, two to four masts with overlapping sails. In India travels in the sixteenth century there were also used carracks, large merchant ships with a high edge and three masts with square sails, that reached 2000 tons.

In the thirteenth century celestial navigation was already known, guided by the sun position. For celestial navigation the Portuguese, like other Europeans, used Arab navigation tools, like the astrolabe and quadrant, which they made easier and simpler. They also created the cross-staff, or cane of Jacob, for measuring at sea the height of the sun and other stars. The Southern Cross become a reference upon arrival at the Southern hemisphere by João de Santarém and Pedro Escobar in 1471, starting the celestial navigation on this constellation. But the results varied throughout the year, which required corrections.

To this the Portuguese used the astronomical tables (Ephemeris), precious tools for oceanic navigation, which have experienced a remarkable diffusion in the fifteenth century. These tables revolutionized navigation, allowing to calculate latitude. The tables of the Almanach Perpetuum, by astronomer Abraham Zacuto, published in Leiria in 1496, were used along with its improved astrolabe, by Vasco da Gama and Pedro Alvares Cabral.

Sailing techniques

Besides coastal exploration, Portuguese also made trips off in the ocean to gather meteorological and oceanographic information (in these were discovered the archipelagoes of Madeira and the Azores, and Sargasso Sea). The knowledge of wind patterns and currents, the trade winds and the oceanic gyres in the Atlantic, and the determination of latitude led to the discovery of the best ocean route back from Africa: crossing the Central Atlantic to the latitude of the Azores, using the permanent favorable winds and currents that spin clockwise in the Northern Hemisphere because of atmospheric circulation and the effect of Coriolis, facilitating the way to Lisbon and thus enabling the Portuguese venturing increasingly farther from shore, the maneuver that became known as the "volta do mar" (English: return of the sea). In 1565, the application of this principle in the Pacific Ocean led the Spanish discovering the Manila Galleon trade route.

Cartography

It is thought that Jehuda Cresques, son of the Catalan cartographer Abraham Cresques have been one of the notable cartographers at the service of Prince Henry. However the oldest signed Portuguese sea chart is a Portolan made by Pedro Reinel in 1485 representing the Western Europe and parts of Africa, reflecting the explorations made by Diogo Cão. Reinel was also author of the first nautical chart known with an indication of latitudes in 1504 and the first representation of an Wind rose.

With his son, cartographer Jorge Reinel and Lopo Homem, they participated in the making of the atlas known as "Lopo Homem-Reinés Atlas" or "Miller Atlas", in 1519. They were considered the best cartographers of their time, with Emperor Charles V wanting them to work for him. In 1517 King Manuel I of Portugal handed Lopo Homem a charter giving him the privilege to certify and amend all compass needles in vessels.

In the third phase of the former Portuguese nautical cartography, characterized by the abandonment of the influence of Ptolemy's representation of the East and more accuracy in the representation of lands and continents, stands out Fernão Vaz Dourado (Goa ~ 1520 - ~ 1580), whose work has extraordinary quality and beauty, giving him a reputation as one of the best cartographers of the time. Many of his charts are large scale.

It was the genius of Prince Henry the Navigator that coordinated and utilized all these tendencies towards expansion. Prince Henry placed at the disposal of his captains the vast resources of the Order of Christ, of which he was the head, and the best information and most accurate instruments and maps that could be obtained. He sought to effect a meeting with the half-fabulous Christian Empire of "Prester John" by way of the "Western Nile" (the Sénégal River), and, in alliance with that potentate, to crush the Turks and liberate the Holy Land. The concept of an ocean route to India appears to have originated after his death. On land he again defeated the Moors, who attempted to retake Ceuta in 1418; but in an expedition to Tangier, undertaken in 1436 by King Edward (1433–1438), the Portuguese army was defeated, and could only escape destruction by surrendering as a hostage Prince Ferdinand, the king's youngest brother. Ferdinand, known as "the Constant", from the fortitude with which he endured captivity, died unransomed in 1443. By sea Prince Henry's captains continued their exploration of Africa and the Atlantic Ocean. In 1433 Cape Bojador was rounded; in 1434 the first consignment of slaves was brought to Lisbon; and slave trading soon became the most profitable branch of Portuguese commerce, until India was reached. The Senegal was reached in 1445, Cape Verde was passed in the same year, and in 1446 Álvaro Fernandes pushed on almost as far as Sierra Leone. This was probably the farthest point reached before the Navigator died in 1460. Another vector of the discoveries were the voyages westward, during which the Portuguese discovered the Sargasso Sea and possibly sighted the shores of Nova Scotia well before 1492.

Treaty of Tordesillas

Meanwhile colonization progressed in the Azores and Madeira, where sugar and wine were now produced; above all, the gold brought home from Guinea stimulated the commercial energy of the Portuguese. It had become clear that, apart from their religious and scientific aspects, these voyages of discovery were highly profitable. Under Afonso V (1443–1481), surnamed the African, the Gulf of Guinea was explored as far as Cape St Catherine (Cabo Santa Caterina),[2] [3] [4] and three expeditions (1458, 1461 and 1471) were sent to Morocco; in 1471 Arzila (Asila) and Tangier were captured from the Moors. Under John II (1481–1495) the fortress of São Jorge da Mina, the modern Elmina, was founded for the protection of the Guinea trade. Diogo Cão, or Can, discovered the Congo in 1482 and reached Cape Cross in 1486; Bartolomeu Dias doubled the Cape of Good Hope in 1488, thus proving that the Indian Ocean was accessible by sea. After 1492 the discovery of the West Indies by Christopher Columbus rendered desirable a delimitation of the Spanish and Portuguese spheres of exploration. This was accomplished by the Treaty of Tordesillas (June 7, 1494) which modified the delimitation authorized by Pope Alexander VI in two bulls issued on May 4, 1493. The treaty gave to Portugal all lands which might be discovered east of a straight line drawn from the Arctic Pole to the Antarctic, at a distance of 370 leagues west of Cape Verde. Spain received the lands discovered west of this line. As, however, the known means of measuring longitude were so inexact that the line of demarcation could not in practice be determined (see J. de Andrade Corvo in Journal das Ciências Matemáticas, xxxi.147-176, Lisbon, 1881), the treaty was subject to very diverse interpretations. On its provisions were based both the Portuguese claim to Brazil and the Spanish claim to the Moluccas (see East Indies#History). The treaty was chiefly valuable to the Portuguese as a recognition of the prestige they had acquired. That prestige was enormously enhanced when, in 1497-1499, Vasco da Gama completed the voyage to India.

Columbus' discovery of what they thought was India at that time, is something that historians dispute in terms of the consequences that lead to this discovery. One theory which has some support, due to recent proof that has come to light, is that Columbus was indeed Portuguese as stated initially, but he was a spy from the Portuguese kingdom sent to Spain to redirect Spain's efforts elsewhere than the territories Portugal had its focus on. However, this is controversial. Actions such as this would come as no surprise, though, since competition between the two kingdoms was intense and both had their secret service networks which were in constant conflict with one another, by providing misleading information and in hiding territories and trade routes discovered by each country (but especially Portugal) by either keeping them concealed or by providing false dates and also false locations. This constant secrecy effort was what led to the creation of many "false" documents and thus many of the remaining documents from that time may not be reliable. As a consequence some historians believe that territories such as Brazil, several African locations along its coastline and North America (due to the voyages made westward) may have been discovered before the known dates.

Afonsine Ordinances

While the Crown was thus acquiring new possessions, its authority in Portugal was temporarily overshadowed by the growth of aristocratic privilege. After the death of Edward, further attempts to curb the power of the nobles were made by his brother, D. Pedro, duke of Coimbra, who acted as regent during the minority of Afonso V of Portugal (1438–1447). The head of the aristocratic opposition was the Duke of Braganza, who contrived to secure the sympathy of the king and the dismissal of the regent. The quarrel led to civil war, and in May 1449, D. Pedro was defeated and killed. Thenceforward the grants made by John I were renewed, and extended on so lavish a scale that the Braganza estates alone comprised about a third of the whole kingdom. An unwise foreign policy simultaneously injured the royal prestige, for Afonso married his own niece, Joanna, daughter of Henry IV of Castile, and claimed the kingdom in her name. At the Battle of Toro, in 1476, he was defeated by Ferdinand and Isabella, and in 1478 he was compelled to sign the Treaty of Alcantara, by which Joanna was relegated to a convent. His successor, John II (1481–1495) reverted to the policy of matrimonial alliances with Castile and friendship with England. Finding, as he said, that the liberality of former kings had left the Crown "no estates except the high roads of Portugal," he determined to crush the feudal nobility and seize its territories. A cortes held at Évora (1481) empowered judges nominated by the Crown to administer justice in all feudal domains. The nobles resisted this infringement of their rights; but their leader, Fernando II, Duke of Braganza, was beheaded for high treason in 1483; in 1484 the king stabbed to death his own brother-in-law, Diogo, Duke of Viseu; and eighty other members of the aristocracy were afterwards executed. Thus John "the Perfect," as he was called, assured the supremacy of the Crown. He was succeeded in 1495 by Emanuel (Manuel) I, who was named "the Great" or "the Fortunate," because in his reign the sea route to India was discovered and a Portuguese Empire founded.

Portuguese in Asia

The effort to colonize and maintain territories scattered around the entire coast of Africa and its surrounding islands, Brazil, the Indies and Indic territories such as in Malaysia, Japan, China, Indonesia and Timor was a challenge for a population of only one million. Combined with constant competition from the Spanish this led to a desire for secrecy about every trade route and every colony. As a consequence, many documents that could reach other European countries were in fact fake documents with fake dates and faked facts, to mislead any other nation's possible efforts.

Archival Material

The tendency to secrecy and falsification of dates casts doubts about the authenticity of many primary sources. Several historians have hypothesized that John II may have known of the existence of Brazil and North America as early as 1480 thus explaining his wish in 1494 at the signing of the Treaty of Tordesillas, to push the line of influence further west. Many historians suspect that the real documents would have been placed in the Library of Lisbon. Unfortunately, due to the fire following the earthquake of 1755, nearly all of the library's records were destroyed[citation needed], but an extra copy available in Goa, was transferred to Lisbon Tower of Tombo, during the following 100 years. The Corpo Cronológico (Chronological Corpus), a collection of manuscripts on the Portuguese explorations and discoveries in Africa, Asia and Latin America, was inscribed on UNESCO’s Memory of the World Register in 2007 in recognition of its historical value "for acquiring knowledge of the political, diplomatic, military, economic and religious history of numerous countries at the time of the Portuguese Discoveries."[5]

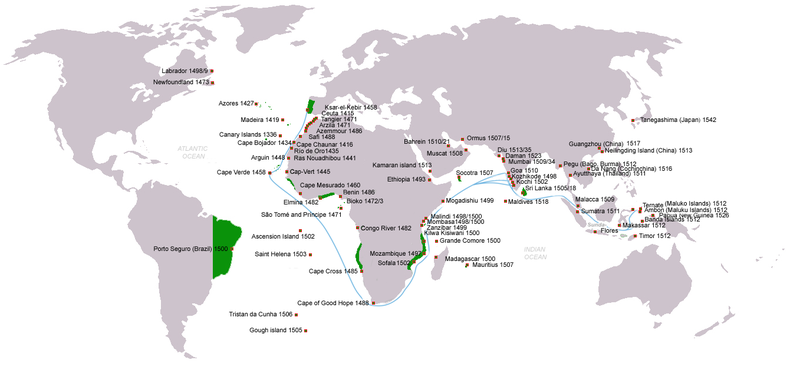

Portuguese discoveries and explorations (1415-1543)

Portuguese discoveries and explorations: first arrival places and dates; main Portuguese spice trade routes in the Indian Ocean (blue); territories of the Portuguese empire under King John III rule (1521-1557) (green)

Portuguese discoveries and explorations: first arrival places and dates; main Portuguese spice trade routes in the Indian Ocean (blue); territories of the Portuguese empire under King John III rule (1521-1557) (green)

Chronology of the Portuguese discoveries

- 1147—Voyage of the Adventurers. Soon before the siege of Lisbon by the crusaders, a Muslim expedition left in search of legendary Islands offshore. They were not heard of again.[citation needed]

- 1336—Possible first expedition to the Canary Islands with additional expeditions in 1340 and 1341, though this is disputed.[6]

- 1412—Prince Henry, the Navigator, orders the first expeditions to the African Coast and Canary Islands.

- 1419—João Gonçalves Zarco and Tristão Vaz Teixeira discovered Porto Santo island, in the Madeira group.

- 1420—The same sailors and Bartolomeu Perestrelo discovered the island of Madeira, which at once began to be colonized.

- 1422—Cape Nao, the limit of Moorish navigation is passed as the African Coast is mapped.

- 1427—Diogo de Silves discovered the Azores, which was colonized in 1431 by Gonçalo Velho Cabral.

- 1434—Gil Eanes sailed round Cape Bojador, thus destroying the legends of the ‘Dark Sea’.

- 1434—the 32 point compass-card replaces the 12 points used until then.

- 1435—Gil Eanes and Afonso Gonçalves Baldaia discovered Garnet Bay (Angra dos Ruivos) and the latter reached the Gold River (Rio de Ouro).

- 1441—Nuno Tristão reached Cape White.

- 1443—Nuno Tristão penetrated the Arguim Gulf. Prince Pedro granted Henry the Navigator the monopoly of navigation, war and trade in the lands south of Cape Bojador.

- 1444—Dinis Dias reached Cape Green (Cabo Verde).

- 1445—Álvaro Fernandes sailed beyond Cabo Verde and reached Cabo dos Mastros (Cape Red)

- 1446—Alvaro Fernandes reached the northern Part of Portuguese Guinea

- 1452—Diogo de Teive discovers the Islands of Flores and Corvo.

- 1458—Luis Cadamosto discovers the first Cape Verde Islands.

- 1460—Death of Prince Henry, the Navigator. His systematic mapping of the Atlantic,reached 8º N on the African Coast and 40º W in the Atlantic (Sargasso Sea) in his lifetime.

- 1461—Diogo Gomes and António Noli discovered more of the Cape Verde Islands.

- 1461—Diogo Afonso discovered the western islands of the Cabo Verde group.

- 1471—João de Santarém and Pedro Escobar crossed the Equator. The southern hemisphere was discovered and the sailors began to be guided by a new constellation, the Southern Cross. The discovery of the islands of São Tome and Principe is also attributed to these same sailors.

- 1472—João Vaz Corte-Real and Álvaro Martins Homem reached the Land of Cod, now called Newfoundland.[citation needed]

- 1479—Treaty of Alcáçovas establishes Portuguese control of the Azores, Guinea, ElMina, Madeira and Cape Verde Islands and Castilian control of the Canary Islands.

- 1482—Diogo Cão reached the estuary of the Zaire (Congo) and placed a landmark there. Explored 150 km upriver to the Ielala Falls.

- 1484—Diogo Cão reached Walvis Bay, south of Namibia.

- 1487—Afonso de Paiva and Pero da Covilhã traveled overland from Lisbon in search of the Kingdom of Prester John. (Ethiopia)

- 1488—Bartolomeu Dias, crowning 50 years of effort and methodical expeditions, rounded the Cape of Good Hope and entered the Indian Ocean. They had found the "Flat Mountain" of Ptolemy's Geography.

- 1489/92—South Atlantic Voyages to map the winds

- 1490—Columbus leaves for Spain after his father-in-law's death.

- 1492—First exploration of the Indian Ocean.

- 1494—The Treaty of Tordesillas between Portugal and Spain divided the world into two parts, Spain claiming all non-Christian lands west of a north-south line 370 leagues west of the Azores, Portugal claiming all non-Christian lands east of that line.

- 1495—Voyage of João Fernandes, the Farmer, and Pedro Barcelos to Greenland. During their voyage they discovered the land to which they gave the name of Labrador (lavrador, farmer)

- 1494—First boats fitted with cannon doors and topsails.

- 1498—Vasco da Gama led the first fleet around Africa to India, arriving in Calicut.

- 1498—Duarte Pacheco Pereira explores the South Atlantic and the South American Coast North of the Amazon River.

- 1500—Pedro Álvares Cabral discovered Brazil on his way to India.

- 1500—Gaspar Corte-Real made his first voyage to Newfoundland, formerly known as Terras Corte-Real.[citation needed]

- 1500—Diogo Dias discovered an island they named after St Lawrence after the saint on whose feast day they had first sighted the island later known as Madagascar

- 1502— Returning from India, Vasco da Gama discovers the Amirante Islands (Seychelles).

- 1502—Miguel Corte-Real set out for New England in search of his brother, Gaspar. João da Nova discovered Ascension Island. Fernão de Noronha discovered the island which still bears his name.

- 1503—On his return from the East, Estevão da Gama discovered Saint Helena Island.

- 1505—Gonçalo Álvares in the fleet of the first viceroy sailed south in the Atlantic to were "water and even wine froze" discovering an island named after him, modern Gough Island

- 1505—Lourenço de Almeida made the first Portuguese voyage to Ceylon (Sri Lanka) and established a settlement there.[7]

- 1506—Tristão da Cunha discovered the island that bears his name. Portuguese sailors landed on Madagascar.

- 1509—The Bay of Bengal crossed by Diogo Lopes de Sequeira. On the crossing he also reached Malacca.

- 1511—Duarte Fernandes is the first European to visit the Kingdom of Siam (Thailand), sent by Afonso de Albuquerque after the conquest of Malaca.[8]

- 1512— António de Abreu discovered Timor island and reached Banda Islands, Ambon Island and Seram. Francisco Serrão reached the Moluccas.

- 1512—Pedro Mascarenhas discover the island of Diego Garcia, he also encountered the Mauritius, although he may not have been the first to do so; expeditions by Diogo Dias and Afonso de Albuquerque in 1507 may have encountered the islands. In 1528 Diogo Rodrigues named the islands of Réunion, Mauritius, and Rodrigues the Mascarene Islands, after Mascarenhas.

- 1512—João de Lisboa and Estevão Frois reached the La Plata estuary or even perhaps the Gulf of San Matias in 42°S in Argentina between 1511 and 1514 (1512) according to the manuscript Newen Zeytung auss Pressilandt in the Fugger archives of the time. Christopher de Haro, the financier of the expedition, bears witness to the trip to La Plata (Rio da Prata) and the news of the "White King" to the interior and west, the Inca emperor - and the axe of silver obtained from the natives and offered to the king Manuel I.

- 1513—The first trading ship to touch the coasts of China, under Jorge Álvares and Rafael Perestrello later in the same year.

- 1517—Fernão Pires de Andrade and Tomé Pires were chosen by Manuel I of Portugal to sail to China to formally open relations between the Portuguese Empire and the Ming Dynasty during the reign of the Zhengde Emperor.

- 1525—Aleixo Garcia explored the Rio de la Plata in service to Spain, as a member of the expedition of Juan Díaz de Solís, and later - from Santa Catarina, Brazil - leading an expedition of some European and 2,000 Guaraní Indians,, explored Paraguay and Bolivia. Aleixo García was the first European to cross the Chaco and even managed to penetrate the outer defenses of the Inca Empire on the hills of the Andes (near Sucre), in present-day Bolivia. He was the first European to do so, accomplishing this eight years before Francisco Pizarro.

- 1526—Discovery of New Guinea; Jorge de Meneses

- 1528—Diogo Rodrigues explores the Mascarene islands, that he names after his countryman Pedro Mascarenhas, he explored and named the islands of Réunion, Mauritius, and Rodrigues[9]

- 1529—Treaty of Saragossa divides the eastern hemisphere between Spain and Portugal, stipulating that the dividing line should lie 297.5 leagues or 17° east of the Moluccas.

- 1542—Fernão Mendes Pinto, Diogo Zeimoto and Cristovão Borralho reached Japan.

- 1542—The coast of California explored by João Rodrigues Cabrilho.

- 1557—Macau (Macao) given to Portugal by the Emperor of China as a reward for services rendered against the pirates who infested the China Sea.

(missing data on Ormuz - from Socotra to Basra, including Muscat, Bahrain, islands in Strait of Hormuz, etc.)

See also

- Portugal

- Portuguese people

- List of Portuguese people

- Naval history

- Portuguese Empire (1415-1999)

- Portuguese colonization of the Americas

- Lusitania

Notes

- ^ Roger Smith, "Vanguard of the Empire", Oxford University Press, 1993, p.30

- ^ Collins, Robert O.; Burns, James M.. "Part II, Chapter 12: The arrival of Europeans in sub-Saharan Africa". A History of Sub-Saharan Africa. Cambridge University Press. p. 179. ISBN 0521867460. "in 1475 when his contract expired Rui de Sequeira had reached Cabo Santa Caterina (Cape Saint Catherine) south of the equator and the Gabon River."

- ^ Arthur Percival, Newton (1970) [1932]. "Vasco da Gama and The Indies". The Great Age of Discovery. Ayer Publishing. p. 48. ISBN 0833725238. "and about the same time Lopo Gonçalves crossed the Equator, while Ruy de Sequeira went on to Cape St. Catherine, two degrees south of the line."

- ^ Koch, Peter O.. "Following the Dream of Prince Henry". To the Ends of the Earth: The Age of the European Explorers. McFarland & Company. p. 62. ISBN 0786415657. "Gomes was obligated to pledge a small percentage of his profits to the royal treasury. Starting from Sierra Leone in 1469, this monetarily motivated entrepreneurial explorer spent the next five years extending Portugal's claims even further than he had been required, reaching as far south as Cape St. Catherine before his contract came up for renewal."

- ^ "Corpo Cronológico (Collection of Manuscripts on the Portuguese Discoveries)". UNESCO Memory of the World Programme. 2008-05-16. http://portal.unesco.org/ci/en/ev.php-URL_ID=22297&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html. Retrieved 2009-12-14.

- ^ B. W. Diffie, Foundations of the Portuguese Empire, 1415 -1580, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, p. 28.

- ^ This article incorporates text from the public domain 1907 edition of The Nuttall Encyclopædia.

- ^ Donald Frederick Lach, Edwin J. Van Kley, Asia in the Making of Europe, p.520-521, University of Chicago Press, 1994, ISBN 9780226467313

- ^ José Nicolau da Fonseca, Historical and Archaeological Sketch of the City of Goa, Bombay : Thacker, 1878, pp. 47-48. Reprinted 1986, Asian Educational Services, ISBN 8120602072.

References

- Braudel, Fernand, The Perspective of the World 1985

Exploration and explorers by nation or region Explorers by country Explorers by type Circumnavigators · Climbers · Desert explorers · Polar explorers · Seafarers · Space travelers · Undersea explorersExploration by region Asia · Central Asia · Africa · Australia · North America · South America · Oceania · Space explorationExploration timelines Portuguese Empire North Africa15th century

1415–1640 Ceuta

1458–1550 Alcácer Ceguer (El Qsar es Seghir)

1471–1550 Arzila (Asilah)

1471–1662 Tangier

1485–1550 Mazagan (El Jadida)

1487– middle 16th century Ouadane

1488–1541 Safim (Safi)

1489 Graciosa16th century

1505–1769 Santa Cruz do Cabo

de Gué (Agadir)

1506–1525 Mogador (Essaouira)

1506–1525 Aguz (Souira Guedima)

1506–1769 Mazagan (El Jadida)

1513–1541 Azamor (Azemmour)

1515 São João da Mamora (Mehdya)

1577–1589 Arzila (Asilah)Sub-Saharan Africa15th century

1455–1633 Arguin

1470–1975 Portuguese São Tomé1

1474–1778 Annobón

1478–1778 Fernando Poo (Bioko)

1482–1637 Elmina (São Jorge

da Mina)

1482–1642 Portuguese Gold Coast

1496–1550 Portuguese Madagascar

1498–1540 Mascarene Islands16th century

1500–1630 Malindi

1500–1975 Portuguese Príncipe1

1501–1975 Portuguese E. Africa

(Mozambique)

1502–1659 Portuguese Saint Helena

1503–1698 Zanzibar

1505–1512 Quíloa (Kilwa)

1506–1511 Socotra

1557–1578 Portuguese Accra

1575–1975 Portuguese W. Africa

(Angola)

1588–1974 Cacheu2

1593–1698 Mombassa (Mombasa)17th century

1642–1975 Portuguese Cape Verde

1645–1888 Ziguinchor

1680–1961 São João Baptista de Ajudá

1687–1974 Portuguese Bissau2

18th century

1728–1729 Mombassa (Mombasa)

1753–1975 Portuguese São Tomé and Príncipe

19th century

1879–1974 Portuguese Guinea

1885–1975 Portuguese Congo1 Part of São Tomé and Príncipe from 1753. 2 Part of Portuguese Guinea from 1879. Southwest Asia16th century

1506–1615 Gamru (Bandar-Abbas)

1507–1643 Sohar

1515–1622 Hormuz (Ormus)

1515–1648 Quriyat

1515–? Qalhat

1515–1650 Muscat

1515?–? Barka

1515–1633? Julfar (Ras al-Khaimah)

1521–1602 Bahrain (Muharraq and Manama)

1521–1529? Qatif

1521?–1551? Tarut Island

1550–1551 Qatif

1588–1648 Matrah17th century

1620–? Khor Fakkan

1621?–? As Sib

1621–1622 Qeshm

1623–? Khasab

1623–? Libedia

1624–? Kalba

1624–? Madha

1624–1648 Dibba Al-Hisn

1624?–? Bandar-e KongIndian subcontinent15th century

1498–1545 Laccadive Islands

(Lakshadweep)16th century

Portuguese India

· 1500–1663 Cochim (Kochi)

· 1502–1661 Quilon (Coulão/Kollam)

· 1502–1663 Cannanore (Kannur)

· 1507–1657 Negapatam (Nagapatnam)

· 1510–1962 Goa

· 1512–1525 Calicut (Kozhikode)

· 1518–1619 Portuguese Paliacate trading outpost (Pulicat)

· 1521–1740 Chaul

· 1523–1662 Mylapore

· 1528–1666 Chittagong

· 1531–1571 Chaul

· 1534–1601 Salsette Island

· 1534–1661 Bombay (Mumbai)

· 1535–1739 Baçaím (Vasai-Virar)

· 1536–1662 Cranganore (Kodungallur)

· 1540–1612 Surat

· 1548–1658 Tuticorin (Thoothukudi)16th century (continued)

Portuguese India (continued)

· 1559–1962 Daman and Diu

· 1568–1659 Mangalore

· 1579–1632 Hugli

· 1598–1610 Masulipatnam (Machilipatnam)

1518–1521 Maldives

1518–1658 Portuguese Ceylon (Sri Lanka)

1558–1573 Maldives

17th century

Portuguese India

· 1687–1749 Mylapore

18th century

Portuguese India

· 1779–1954 Dadra and Nagar HaveliEast Asia and Oceania16th century

1511–1641 Portuguese Malacca

1512–1621 Portuguese Maluku Islands

· 1522–1575 Ternate

· 1576–1605 Ambon

· 1578–1650 Tidore

1512–1665 Makassar

1553–1999 Portuguese Macau

1571–1639 Decima (Dejima, Nagasaki)17th century

1642–1975 Portuguese Timor (East Timor)1

19th century

Portuguese Macau

· 1864–1999 Coloane

· 1849–1999 Portas do Cerco

· 1851–1999 Taipa

· 1890–1999 Ilha Verde

20th century

Portuguese Macau

· 1938–1941 Lapa and Montanha (Hengqin)1 1975 is the year of East Timor's Declaration of Independence and subsequent invasion by Indonesia. In 2002, East Timor's independence was recognized by Portugal & the world.

North America and the North Atlantic Ocean16th century

1500–1579? Terra Nova (Newfoundland)

1500–1579? Labrador

1516–1579? Nova ScotiaCentral and South America16th century

1500–1822 Brazil

1536–1620 Portuguese Barbados17th century

1680–1777 Nova Colónia do Sacramento

19th century

1808–1822 Cisplatina (Uruguay)

1809–1817 Portuguese Guiana

1822 Upper PeruCategories:- Portuguese discoveries

- History of Portugal

- Age of Discovery

- Portuguese Empire

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.