- Chinese exploration

-

Chinese exploration includes exploratory Chinese travels abroad, on land and by sea, from the 2nd century BC until the 15th century.

Contents

Land exploration

Pamir Mountains and beyond

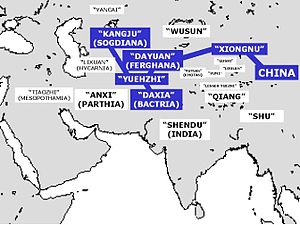

Further information: History of the Han DynastyBy traveling past the Tarim Basin region, the Chinese of the Han Dynasty learned of powerful kingdoms in Central Asia, Persia, India, and the Middle East with the travels of the Han Dynasty envoy Zhang Qian in the 2nd century BC. From 104 BC to 102 BC Emperor Wu of Han waged war against the Yuezhi who controlled Dayuan, a Hellenized kingdom of Fergana established by Alexander the Great in 329 BC. Gan Ying, the emissary of General Ban Chao, perhaps traveled as far as Roman-era Syria in the late 1st century AD. After these initial discoveries the focus of Chinese exploration shifted to the maritime sphere, although the Silk Road leading all the way to Europe continued to be China's most lucrative source of trade. Later, the Buddhist Xuanzang traveled from Chang'an to the west on land in his starting and returning journeys.

Maritime exploration

South China Sea

Before the advent of the Chinese-invented mariner's compass in the 11th century, the seasonal monsoon winds aided one in navigation, blowing north from the equatorial zone in the summer and south in the winter.[1] This most likely accounts for the ease in which Neolithic age travelers from mainland China could to settle on the island of Taiwan in prehistoric times.[1] After defeating the last of the Warring States and consolidating an empire over China proper, the Chinese navy of the Qin Dynasty period (221 BC—207 BC) sailed down into the South China Sea and conquered the peoples of modern-day Guangzhou and northern Vietnam (then called Jiaozhi and then Annam).[1] The northern half of Vietnam would not become fully independent from Chinese rule until the 10th century (938 AD). In 1975, an ancient shipyard excavated in Guangzhou was dated to the early Han Dynasty (202 BC –220 AD), and with three platforms was able to construct ships that were approximately 30 m (98 ft) in length, 8 m (26 ft) in width, and could hold a weight of 60 metric tons.[2]

In 403 a rebel of Eastern Jin known as Lu Xun managed to fend off an attack by the imperial army for a hundred days before he sailed down into the South China Sea from a coastal commandery. For six years, Lu Xun occupied Panyu, the largest southern seaport of that time.[3]

Travellers from Wu kingdom like Zhu Ying and Kang Tai are known to have visited Cambodia between 226-231, and reported to have met two Chinese envoys there sent by the Indian king. Although two books which they wrote have not survived, fragments remain in the Shuijingzhu, Yiwen Leiju, etc.[4]

Indian Ocean and beyond

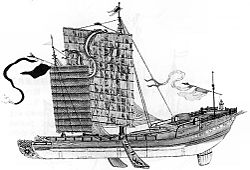

A Song Dynasty junk ship, 13th century; Chinese ships of the Song period featured hulls with watertight compartments

A Song Dynasty junk ship, 13th century; Chinese ships of the Song period featured hulls with watertight compartments

Chinese envoys sailed into the Indian Ocean from the late 2nd century BC, and reportedly reached Kanchipuram, known as Huangzi (黄支) to them,[5][6] or otherwise Ethiopia as asserted by Ethiopian scholars.[7] During the late 4th and early 5th centuries, Chinese pilgrims like Faxian, Zhiyan, and Tanwujie began traveling by sea to India, bringing back Buddhist scriptures and sutras to China.[8] By the 7th century as many as 31 recorded Chinese monks including I Ching managed to reach India the same way. In 674 the private explorer Daxi Hongtong was among the first to end his journey at the southern tip of the Arabian Peninsula, after traveling through 36 countries west of the South China Sea.[9]

Chinese seafaring merchants and diplomats of the medieval Tang Dynasty (618—907) and Song Dynasty (960—1279) often sailed into the Indian Ocean after visiting ports in South East Asia. Chinese sailors would travel to Malaya, India, Sri Lanka, into the Persian Gulf and up the Euphrates River in modern-day Iraq, to the Arabian peninsula and into the Red Sea, stopping to trade goods in Ethiopia and Egypt (as Chinese porcelain was highly-valued in old Fustat, Cairo).[10] Jia Dan wrote Route between Guangzhou and the Barbarian Sea during the late 8th century that documented foreign communications, the book was lost, but the Xin Tangshu retained some of his passages about the three sea-routes linking China to East Africa.[11] Jia Dan also wrote about tall lighthouse minarets in the Persian Gulf, which were confirmed a century later by Ali al-Masudi and al-Muqaddasi.[12] Beyond the initial work of Jia Dan, other Chinese writers accurately describing Africa from the 9th century onwards; For example, Duan Chengshi wrote in 863 of the slave trade, ivory trade, and ambergris trade of Berbera, Somalia.[13] Seaports in China such as Guangzhou and Quanzhou - the most cosmopolitan urban centers in the medieval world - hosted thousands of foreign travelers and permanent settlers. Chinese junk ships were even described by the Moroccan geographer Al-Idrisi in his Geography of 1154, along with the usual goods they traded and carried aboard their vessels.[14]

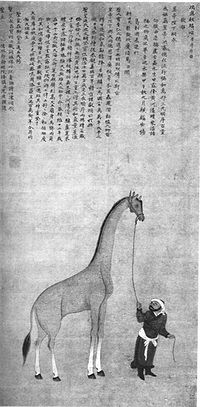

From 1405 to 1433 large fleets commanded by Admiral Zheng He under the auspices of the Yongle Emperor of the Ming Dynasty traveled to the Western Ocean (the Chinese name for the Indian Ocean) seven times. This attempt did not lead China to global expansion, as the Confucian bureaucracy under next emperor reversed this whole policy and by 1500, it became a capital offence to build a seagoing junk with more than two masts.[15] Chinese became content trading with already existing tributary states nearby and abroad. To them, traveling far east into the Pacific Ocean represented entering a broad wasteland of water with uncertain benefits of trade. While British amateur historian Gavin Menzies once asserted in his book 1421: The Year China Discovered the World that Zheng likely traveled as far as the Americas, this is not supported by scholarship and there is no evidence to suggest that this is the case.

Exchanges

The Muslim traveler Sa`d ibn Abi Waqqas has been traditionally credited by Chinese Muslims with introducing Islam to China in 650, during the reign of Emperor Gaozong of Tang,[16][17] although modern secular scholars don't find any historical evidence for him actually travelling to China.[18] It is also well documented[citation needed] that in the year 1008 the Fatimid Egyptian sea captain Domiyat, in the name of his ruling Imam Al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah, travelled to the Buddhist pilgrimage site in Shandong in order to seek out Emperor Zhenzong of Song with gifts from his court.[19] This reestablished diplomatic ties between China and Egypt which had been lost since the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period (907-960).[19] There was also the trade embassy of the Indian ruler Kulothunga Chola I to the court of Emperor Shenzong of Song in 1077, which proved to be an economic benefactor for both empires.[20]

For more see Tang Dynasty, History of the Song Dynasty, and Islam during the Song Dynasty.

Technique

In China, the invention of the stern-mounted rudder appeared as early as the 1st century AD, allowing for better steering than using the power of oarsmen. The Cao Wei Kingdom engineer and inventor Ma Jun (c. 200—265 AD) built the first South Pointing Chariot, a complex mechanical device that incorporated a differential gear in order to navigate on land, and (as one 6th century text alludes) by sea as well.[21][22] Much later the Chinese polymath scientist Shen Kuo (1031—1095 AD) was the first to describe the magnetic needle-compass, along with its usefulness for accurate navigation by discovering the concept of true north.[23][24] In his Pingzhou Table Talks of 1119 AD the Song Dynasty maritime author Zhu Yu described the use of separate bulkhead compartments in the hulls of Chinese ships.[25] This allowed for water-tight conditions and ability of a ship not to sink if one part of the hull became damaged.[25]

See also

- Age of Discovery

- List of Chinese discoveries

- Maritime history

- Naval history

- Naval history of China

- 1421 Hypothesis

- Chinese geography

- List of China-related topics

Notes

- ^ a b c Fairbank, 191.

- ^ Wang (1982), 122.

- ^ Sun 1989, p. 201

- ^ Sun 1989, p.191-193

- ^ Sun 1989, p. 161-167

- ^ Chen 2002, p. 67-71

- ^ A Chinese in the Nubian and Abyssinian Kingdoms (8th century), Wolbert Smidt.

- ^ Sun 1989, p. 220-221

- ^ Sun 1989, p. 316-321

- ^ Bowman, 104-105.

- ^ Sun, p. 310-314

- ^ Needham, Volume 4, Part 3, 661.

- ^ Levathes, 38.

- ^ Shen, 159-161.

- ^ Ronan, Colin; Needham, Joseph (1986), The shorter Science and Civilisation in China, 3, C.U.P., p. 147

- ^ Wang, Lianmao (2000). Return to the City of Light: Quanzhou, an eastern city shining with the splendour of medieval culture. Fujian People's Publishing House. Page 99.

- ^ Lipman, Jonathan Neaman (1997). Familiar strangers: a history of Muslims in Northwest China. University of Washington Press. p. 29. ISBN 9622094686. http://books.google.com/books?id=4_FGPtLEoYQC.

- ^ Lipman, p. 25

- ^ a b Shen, 158.

- ^ Sastri, 173, 316.

- ^ Needham, Volume 4, Part 2, 40.

- ^ Needham, Volume 4, Part 2, 287-288

- ^ Bowman, 599.

- ^ Sivin, III, 22.

- ^ a b Needham, Volume 4, Part 3, 463.

References

- Bowman, John S. (2000). Columbia Chronologies of Asian History and Culture. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Chen, Yan (2002). Maritime Silk Route and Chinese-Foreign Cultural Exchanges. Beijing: Peking University Press. ISBN 7-301-03029-0.

- Fairbank, John King and Merle Goldman (1992). China: A New History; Second Enlarged Edition (2006). Cambridge: MA; London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-01828-1

- Levathes (1994). When China Ruled the Seas. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-70158-4.

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Technology, Part 2, Mechanical Engineering. Taipei: Caves Books Ltd.

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Technology, Part 3, Civil Engineering and Nautics. Taipei: Caves Books Ltd.

- Sastri, Nilakanta, K.A. The CōĻas, University of Madras, Madras, 1935 (Reprinted 1984).

- Shen, Fuwei (1996). Cultural flow between China and the outside world. Beijing: Foreign Languages Press. ISBN 7-119-00431-X.

- Sivin, Nathan (1995). Science in Ancient China: Researches and Reflections. Brookfield, Vermont: VARIORUM, Ashgate Publishing.

- Sun, Guangqi (1989). History of Navigation in Ancient China. Beijing: Ocean Press. ISBN 7-5027-0532-5.

- Wang, Zhongshu. (1982). Han Civilization. Translated by K.C. Chang and Collaborators. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 0300027230.

Categories:- Maritime history

- History of China

- Age of Discovery

- History of foreign trade in China

- History of the foreign relations of China

- Chinese explorers

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.