- Douglas Mawson

-

"Mawson" redirects here. For other uses, see Mawson (disambiguation).

Douglas Mawson

Sir Douglas Mawson in 1914Born 5 May 1882

Shipley, West Yorkshire, England, United KingdomDied 14 October 1958 (aged 76)

Brighton, South Australia, AustraliaNationality  Australian

AustralianOccupation Geologist, Antarctic Explorer and Academic Known for First ascent of Mount Erebus

First team to reach the South Magnetic Pole

Sole survivor of the Far Eastern PartySpouse Francisca Paquita Delprat (1914) Children Patricia (b.1915)

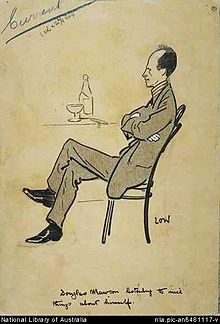

Jessica (b.1917) Caricature by Sir David Low

Caricature by Sir David Low

Sir Douglas Mawson, OBE, FRS, FAA (5 May 1882 – 14 October 1958) was an Australian geologist, Antarctic explorer and Academic. Along with Roald Amundsen, Robert Falcon Scott, and Ernest Shackleton, Mawson was a key expedition leader during the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration.

Contents

Early work

He was appointed geologist to an expedition to the New Hebrides (now Vanuatu) in 1903; his report The geology of the New Hebrides, was one of the first major geological works of Melanesia. Also that year he published a geological paper on Mittagong, New South Wales. His major influences in his geological career were Professor Edgeworth David and Professor Archibald Liversidge. He then became a lecturer in petrology and mineralogy at the University of Adelaide in 1905.[1] He identified and first described the mineral Davidite, named for Edgeworth David.

Australasian Antarctic Expedition

Douglas turned down an invitation to join Robert Falcon Scott's Terra Nova Expedition in 1910; Australian geologist Griffith Taylor went with Scott instead. Mawson chose to lead his own expedition, the Australasian Antarctic Expedition, to King George V Land and Adelie Land, the sector of the Antarctic continent immediately south of Australia, which at the time was almost entirely unexplored. The objectives were to carry out geographical exploration and scientific studies, including a visit to the South Magnetic Pole.

The expedition, using the ship SY Aurora commanded by Captain John King Davis, departed Hobart on 2 December 1911, landed at Cape Denison on Commonwealth Bay on 8 January 1912, and established the Main Base. A second camp was located to the west on the ice shelf in Queen Mary Land. Cape Denison proved to be unrelentingly windy; the average wind speed for the entire year was about 50 mph (80 km/h), with some winds approaching 200 mph. They built a hut on the rocky cape and wintered through nearly constant blizzards. Mawson wanted to do aerial exploration and brought the first aeroplane to Antarctica. The aircraft, a Vickers R.E.P. Type Monoplane,[2] was to be flown by Francis Howard Bickerton. When it was damaged in Australia shortly before the expedition departed, plans were changed so it was to be used only as a tractor on skis. However, the engine did not operate well in the cold, and it was removed and returned to Vickers in England. The aircraft fuselage itself was abandoned. On 1 January 2010, fragments of it were rediscovered by the Mawson's Huts Foundation, which is restoring the original huts.[3]

Mawson's exploration program was carried out by five parties from the Main Base and two from the Western Base. Mawson himself was part of a three-man sledging team, the Far Eastern Party, with Xavier Mertz and Lieutenant Belgrave Ninnis, who headed east on 10 November 1912, to survey King George V Land. After five weeks of excellent progress mapping the coastline and collecting geological samples, the party was crossing the Ninnis Glacier 480 km east of the main base. Mertz was skiing and Mawson was on his sled with his weight dispersed, but Ninnis was jogging beside the second sled. Ninnis fell through a snow-covered crevasse, and his body weight is likely to have breached the lid. The six best dogs, most of the party's rations, their tent, and other essential supplies disappeared into the massive crevasse. Mertz and Mawson spotted one dead and one injured dog on a ledge 50 m below them, but Ninnis was never seen again.[4]

After a brief service, Mawson and Mertz turned back immediately. They had one week's provisions for three men and no dog food but plenty of fuel and a primus. They sledged for 27 hours continuously to obtain a spare tent cover they had left behind, for which they improvised a frame from skis and a theodolite. Their lack of provisions forced them to use their remaining sled dogs to feed the other dogs and themselves:

"Their meat was tough, stringy and without a vestige of fat. For a change we sometimes chopped it up finely, mixed it with a little pemmican, and brought all to the boil in a large pot of water. We were exceedingly hungry, but there was nothing to satisfy our appetites. Only a few ounces were used of the stock of ordinary food, to which was added a portion of dog's meat, never large, for each animal yielded so very little, and the major part was fed to the surviving dogs. They crunched the bones and ate the skin, until nothing remained."[5]

There was a quick deterioration in the men's physical condition during this journey. Both men suffered dizziness; nausea; abdominal pain; irrationality; mucosal fissuring; skin, hair, and nail loss; and the yellowingf of eyes and skin. Later Mawson noticed a dramatic change in his travelling companion. Mertz seemed to lose the will to move and wished only to remain in his sleeping bag. He began to deteriorate rapidly with diarrhoea and madness. On one occasion Mertz refused to believe he was suffering from frostbite and bit off the tip of his own little finger. This was soon followed by violent raging—Mawson had to sit on his companion's chest and hold down his arms to prevent his damaging their tent. Mertz suffered further seizures before falling into a coma and dying on 8 January 1913.[6]

It was unknown at the time that Husky liver contains extremely high levels of vitamin A. It was also not known that such levels of vitamin A is poisonous to humans.[7] With six dogs between them (with a liver on average weighing 1 kg), it is thought that the pair ingested enough liver to bring on a condition known as Hypervitaminosis A. However, Mertz may have suffered more because he found the tough muscle tissue difficult to eat and therefore ate more of the liver than Mawson .[8]. It is of interest to note that in Eskimo tradition the dog's liver is never eaten. While both men suffered Mertz suffered chronically. Another theory has suggested the reason he suffered worse was because he had been a vegetarian. A 2005 article in The Medical Journal of Australia by Denise Carrington-Smith, noting that Mertz was essentially a vegetarian, suggested that the sudden change to a predominantly meat diet could have triggered Mertz's illness. Combined with "the psychological stresses related to the death of a close friend [Ninnis] and the deaths of the dogs he had cared for, as well as the need to kill and eat his remaining dogs," this may have killed Mertz.[9]

Mawson continued the final 100 miles alone. During his return trip to the Main Base he fell through the lid of a crevasse, and was saved only by his sledge wedging itself into the ice above him. He was forced to climb out using the harness attaching him to the sled.

When Mawson finally made it back to Cape Denison, the ship Aurora had left only a few hours before. It was recalled by wireless communication, only to have bad weather thwart the rescue effort. Mawson and six men who had remained behind to look for him, wintered a second year until December 1913. In Mawson's book Home of the Blizzard, he describes his experiences. His party, and those at the Western Base, had explored large areas of the Antarctic coast, describing its geology, biology and meteorology, and more closely defining the location of the south magnetic pole. In 1916, the American Geographical Society awarded Mawson the David Livingstone Centenary Medal.[10]

Home of the Blizzard

In his book, The Home of the Blizzard, Mawson talked of "Herculean gusts" on 24 May 1912 which he learned afterwards "approached two hundred miles per hour",[11] and that the average wind velocity for March was 49 miles per hour; April 51.5 miles per hour and May was 67.719 miles per hour.[12] These winds have been referred to as katabatic: "a wind that carries high density air from a higher elevation down a slope under the force of gravity (south magnetic pole)".[13]

Later life

Mawson married Francisca Adriana(Paquita) Delprat on 31 March 1914 at Holy Trinity Church of England, Balaclava, Victoria. They had two daughters, Patricia and Jessica. Also in 1914, he was knighted, and was completely taken up[vague] with the Scott disaster and the outbreak of World War I. Mawson served in the war as a Major in the British Ministry of Munitions. Returning to Adelaide he pursued his academic studies, taking further expeditions abroad, including a joint British, Australian and New Zealand expedition to the Antarctic in 1929–31. The work done by the British Australian and New Zealand Antarctic Research Expedition led to the formation of the Australian Antarctic Territory in 1936. He also spent much of his time researching the geology of the northern Flinders Ranges in South Australia. Upon his retirement from teaching in 1952 he was made Emeritus Professor of the University of Adelaide. He died at his Brighton home on 14 October 1958 from a cerebral haemorrhage.[14] He was 76 years old. At the time of his death he had still not completed editorial work on all the papers resulting from his expedition, and this was only completed by his eldest daughter, Patricia, in 1975.

His image appeared from 1984–96 on the Australian paper one hundred dollar note. Mawson Peak (Heard Island), Mount Mawson (Tasmania), Mawson Station (Antarctica), Dorsa Mawson (Mare Fecunditatis), the geology building on the main University of Adelaide campus, suburbs in Canberra and Adelaide, a South Australian TAFE institute, and the main street of Meadows, South Australia are named after him. At Oxley College in Burradoo, New South Wales, a sports house is called Mawson, as is at Clarence High School in Hobart, Tasmania. The Mawson Collection of Antarctic exploration artefacts is on permanent display at the South Australian Museum, including a screening of a recreated version of his journey that was shown on ABC Television on 12 May 2008.

See also

References

- ^ "Douglas Mawson". Australian Dictionary of Biography. http://www.adb.online.anu.edu.au/biogs/A100444b.htm. Retrieved 2007-10-01.

- ^ CDWS-1 Air tractor tail

- ^ Relic of Antarctica's first plane discovered on ice edge

- ^ http://www.south-pole.com/p0000099.htm www.south-pole.com

- ^ Douglas Mawson. "The Home of the Blizzard". http://www.gutenberg.org/files/6137/6137-h/6137-h.htm#2HCH0013.

- ^ Bickel, Lennard (2000). Mawson's Will: The Greatest Polar Survival Story Ever Written, Hanover, New Hampshire: Steerforth Press. ISBN 1-58642-000-3

- ^ Vitamin A toxicity

- ^ "Man's Best Friend?". Student BMJ 2002;10:131–170 May. http://archive.student.bmj.com/issues/02/05/life/158.php. Retrieved 2009-11-11.

- ^ Carrington-Smith (2005), p. 641

- ^ "The Cullum Geographical Medal". American Geographical Society. Retrieved 17 June 2010.

- ^ Mawson, D: "The Home of the Blizzard, Vol I", page 133, J. B. Lippincott, no date

- ^ Mawson, D: "The Home of the Blizzard, Vol I", page 134, J. B. Lippincott, no date

- ^ Australian Antarctic Division – Sir Douglas Mawson

- ^ Mawson, Sir Douglas (1882–1958) Biographical Entry – Australian Dictionary of Biography Online

Sources

- Bickel, Lennard [1977] (2001). This Accursed Land, foreword by Sir Edmund Hillary, Edinburgh: Birlinn Ltd. ISBN 1841581410.

- Caesar, Adrian:The White: Last Days in the Antarctic Journeys of Scott and Mawson 1911–1913 Pan MacMillan, Sydney, 1999, ISBN 0-330-36157-0

- Jacka, F. J. "Mawson, Sir Douglas (1882–1958)", Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 10, MUP, 1986, pp 454–457.

- Hall, Lincoln (2000) Douglas Mawson, The Life of an Explorer New Holland, Sydney ISBN 1864366702

- Mawson, Sir Douglas (no date given) The Home of the Blizzard, being the story of the Australasian Antarctic expedition, 1911–1914 Vol. I, London: Ballantyne Press.

- Carrington-Smith, Denise (2005). "Mawson and Mertz: a re-evaluation of their ill-fated mapping journey during the 1911–1914 Australasian Antarctic Expedition.". The Medical Journal of Australia 183 (11–12): pp. 638–41. PMID 16336159

- Roberts, Peder (2004). "Fighting the 'microbe of sporting mania': Australian science and Antarctic exploration in the early 20th century". Endeavour 28 (3): pp. 109–113. 2004 Sep. doi:10.1016/j.endeavour.2004.07.005]. PMID 15350758

External links

- Mawson's Antarctic Newspaper Mawson's Antarctic Newspaper, article in www.TheGlobalDispatches.com

- Mawson, Douglas (Sir) (1882–1958) National Library of Australia, Trove, People and Organisation record for Sir Douglas Mawson

- Douglas Mawson in Antarctica

- Hurley, Frank. Collection of Photographic Prints. Images of Mawson Expedition 1911–14 held at Pictures Branch, National Library of Australia, Canberra

- National Archives of Australia

Awards Preceded by

G. W. CardClarke Medal

1936Succeeded by

John Thomas JutsonAustralasian Antarctic Expedition Personnel Main Base party- Bob Bage

- Frank Bickerton

- John Close

- Percy Correll

- Walter Hannam

- Alfred Hodgeman

- John Hunter

- Frank Hurley

- Sidney Jeffryes

- Charles Laseron

- Cecil Madigan

- Douglas Mawson

- Archibald McLean

- Xavier Mertz

- Herbert Murphy

- B. E. S. Ninnis

- Frank Stillwell

- Eric Webb

- Leslie Whetter

Western Base party- Charles Dovers

- Charles Harrisson

- Charles Hoadley

- Sydney Jones

- Alexander Kennedy

- Morton Moyes

- Andrew Watson

- Frank Wild

Macquarie Island party- George Ainsworth

- Leslie Blake

- Harold Hamilton

- Charles Sandell

- Arthur Sawyer

SY Aurora officers- John H. Blair

- John King Davis

- Frank D. Fletcher

- F. J. Gillies

- Percival Gray

- Clarence Petersen de la Motte

- Norman Toutcher

Other- Hugh Evelyn Watkins

Parties and vessels - Far Eastern Party

- SY Aurora

- Western Base Party

Places - Adélie Land

- Cape Denison

- Commonwealth Bay

- King George V Land

- Macquarie Island

- Mertz Glacier

- Ninnis Glacier

- Queen Mary Land

- Shackleton Ice Shelf

- Wireless Hill

Other - Adélie Land meteorite

- Air-tractor sledge

- Mawson's Huts

Antarctica Main articles - Antarctic

- History

- Geography

- Climate

- Expeditions

- Research stations

- Field camps

- Territorial claims

- Antarctic Treaty System

- Telecommunications

- Demographics

- Economy

- Tourism

- Transport

- Military activity in the Antarctic

Geographic regions - Antarctic Peninsula

- East Antarctica

- West Antarctica

- Extreme points of the Antarctic

- List of Antarctic and subantarctic islands

- Antarctica ecozone

Waterways Famous explorers - Ernest Shackleton

- James Clark Ross

- Richard E. Byrd

- Roald Amundsen

- Douglas Mawson

- Robert Falcon Scott

- more...

Categories:- 1882 births

- 1958 deaths

- Australian explorers

- Australian geologists

- Explorers of Antarctica

- Fellows of the Australian Academy of Science

- Fellows of the Royal Society

- Officers of the Order of the British Empire

- People from Adelaide

- Knights Bachelor

- Jubilee 150 Walkway

- Sole survivors

- People associated with Macquarie Island

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.