- Terra Nova Expedition

-

Scott's party at the South Pole, 18 January 1912. L to R: (standing) Oates, Scott, Wilson; (seated) Bowers, Edgar Evans

Scott's party at the South Pole, 18 January 1912. L to R: (standing) Oates, Scott, Wilson; (seated) Bowers, Edgar Evans

The Terra Nova Expedition (1910–1912), officially the British Antarctic Expedition 1910, was led by Robert Falcon Scott with the objective of being the first to reach the geographical South Pole. Scott and four companions attained the pole on 17 January 1912, to find that a Norwegian team led by Roald Amundsen had preceded them by 33 days. Scott's entire party died on the return journey from the pole; some of their bodies, journals, and photographs were discovered by a search party eight months later.

Scott was an experienced polar commander, having previously led the Discovery Expedition to the Antarctic in 1901–04. The Terra Nova Expedition, named after its supply ship, was a private venture, financed by public contributions augmented by a government grant. It had further backing from the Admiralty, which released experienced seamen to the expedition, and from the Royal Geographical Society. As well as its polar attempt, the expedition carried out a comprehensive scientific programme, and explored Victoria Land and the Western Mountains. An attempted landing and exploration of King Edward VII Land was unsuccessful. A journey to Cape Crozier in June and July 1911 was the first extended sledging journey in the depths of the Antarctic winter.

For many years after his death, Scott's status as tragic hero was unchallenged, and few questions were asked about the causes of the disaster which overcame his polar party. In the final quarter of the 20th century the expedition came under closer scrutiny, and more critical views were expressed about its organisation and management. The degree of Scott's personal culpability remains a matter of controversy among commentators.

Contents

Preparations

Background

After Discovery's return from the Antarctic in 1904, Scott eventually resumed his naval career, but continued to nurse ambitions of returning south, with the conquest of the Pole as his specific target.[1] The Discovery Expedition had made a significant contribution to Antarctic scientific and geographical knowledge, but in terms of penetration southward had only reached 82° 17′ and had not traversed the Great Ice Barrier.[2][A] In 1909 Scott received news that Ernest Shackleton's Nimrod Expedition had narrowly failed to reach the Pole. Starting from a base close to Scott's Discovery anchorage in McMurdo Sound, Shackleton had crossed the Great Ice Barrier, discovered the Beardmore Glacier route to the Polar Plateau, and had struck out for the Pole. He had been forced to turn for home at 88° 23′ S, less than 100 geographical miles (112 statute miles, 180 km) from his objective.[3] However, Scott claimed prescriptive rights to the McMurdo Sound area, describing it as his own "field of work",[4] and Shackleton's use of the area as a base was in breach of an undertaking not to do so.[5] This soured relations between the two explorers, and increased Scott's determination to surpass Shackleton's achievements.[6]

As he made his preparations for a further expedition, Scott was aware of other polar ventures being planned. A Japanese expedition was in the offing;[7] the Australasian Antarctic Expedition under Douglas Mawson was to leave in 1911, but would be working in a different sector of the continent.[8] Meanwhile, Roald Amundsen, a potential rival, had announced plans for an Arctic voyage.[9][10]

Personnel

Sixty-five men (including replacements) formed the shore and ship's parties of the Terra Nova Expedition.[11] They were chosen from 8,000 applicants,[12] and included six Discovery veterans together with five who had been with Shackleton on his 1907–09 expedition.[B] Lieutenant E R G R ("Teddy") Evans, who had been the navigating officer on Morning during the Discovery relief operation in 1904, was appointed Scott's second-in-command. He abandoned plans to mount his own expedition, and transferred his financial backing to Scott.[13]

Among the serving Royal Navy (RN) personnel released by the Admiralty were Lieutenant Harry Pennell, who would serve as navigator and take command of the ship once the shore parties had landed,[14] and two Surgeon-Lieutenants, George Murray Levick and Edward L Atkinson.[14] Ex-RN officer Victor Campbell, known as "The Wicked Mate", was one of the few who had skills in skiing, and was chosen to lead the party that would explore King Edward VII Land.[15][16] The Admiralty also provided a largely naval lower deck, including the Antarctic veterans Edgar Evans, Tom Crean and William Lashly. Two non-naval officers were appointed: Henry Robertson Bowers, known as "Birdie", who was a lieutenant in the Royal Indian Marine,[14] and Lawrence Oates ("Titus"), an Army captain from the 6th (Inniskilling) Dragoons. Oates, independently wealthy, volunteered his services to the expedition and paid £1,000 (2009 value approximately £75,000[17]) into its funds.[18]

To head his scientific programme, Scott appointed Edward Wilson as chief scientist. Wilson was Scott's closest confidant among the party; on the Discovery expedition he had accompanied Scott on the Farthest South march. A distinguished research zoologist, he was also a talented illustrator. His scientific team—in the words of Scott's biographer David Crane "as impressive a group of scientists as had ever been on a polar expedition"[14]—included some who would enjoy later careers of distinction: George Simpson the meteorologist, Charles Wright, the Canadian physicist, and geologists Frank Debenham and Raymond Priestley.[19] T. Griffith Taylor, the senior of the geologists, biologist Edward William Nelson and assistant zoologist Apsley Cherry-Garrard completed the team. Cherry-Garrard had no scientific training, but was a protege of Wilson's. He had, like Oates, contributed £1,000 to funds. After first being turned down by Scott, he allowed his contribution to stand, which impressed Scott sufficiently for him to reverse his decision.[19] Scott's biographer David Crane describes Cherry-Garrard as "the future interpreter, historian and conscience of the expedition."[20] Herbert Ponting was the expedition's photographer, whose pictures would leave a vivid visual record.[21] On the advice of Fridtjof Nansen, Scott recruited a young Norwegian ski expert, Tryggve Gran.[22]

Transport

Scott had decided on a mixed transport strategy, relying on contributions from dogs, motor sledges and ponies.[23][24] He appointed Cecil Meares to take charge of the dog teams, and recruited Shackleton's former motor specialist, Bernard Day, to run the motor sledges.[25] Oates would be in charge of the ponies, but as he could not join the expedition until May 1910 Scott instructed Meares, who knew nothing of horses, to buy them—with unfortunate consequences for their quality and performance.[26]

Motor traction and the use of ponies had been pioneered in the Antarctic by Shackleton, on his 1907–09 expedition.[27][28] Scott believed that ponies had served Shackleton well, and he was impressed by the potential of motors. However, Scott always intended to rely on man-hauling for much of his polar journey;[29] the other methods would be used to haul loads across the Barrier, enabling the men to preserve their strength for the later Glacier and Plateau stages. In practice, the motor sledges proved only briefly useful, and the ponies' performance was affected by their age and poor condition.[30] As to dogs, while Scott's experiences on Discovery had made him dubious of their reliability,[31] his writings show that he recognised their effectiveness in the right hands.[32] As the expedition developed, he became increasingly impressed with their capabilities.[C]

Finance

The Oxo food company was one of many commercial sponsors of the expedition.

The Oxo food company was one of many commercial sponsors of the expedition.

Unlike the Discovery expedition, where fundraising was handled jointly by the Royal Society and the Royal Geographical Society, the Terra Nova Expedition was organised as a private venture without significant institutional support. Scott estimated the total cost at £40,000 (£3 million at 2009 values),[17][33] half of which was eventually met by a government grant.[34] The balance was raised by public subscription and loans.[D] The expedition was further assisted by the free supply of a range of provisions and equipment from sympathetic commercial firms.[35] The fund-raising task was largely carried out by Scott, and was a considerable drain on his time and energy, continuing in South Africa, Australia, and New Zealand after Terra Nova had sailed from British waters.[36]

By far the largest single cost was the purchase of the ship Terra Nova, for £12,500.[34] The Terra Nova had been in Antarctica before, as part of the second Discovery relief operation.[37] Scott wanted to sail her as a Naval vessel under the White Ensign; to enable this, he obtained membership of the Royal Yacht Squadron for the sum of £100. He was thus able to impose Naval discipline on the expedition, and as a registered yacht of the Squadron, Terra Nova became exempt from Board of Trade regulations which might otherwise have deemed her unfit to sail.[38]

Objectives

Scott defined the objects of the expedition in his initial public appeal: "The main objective of this expedition is to reach the South Pole, and to secure for The British Empire the honour of this achievement."[33] There were other objectives, both scientific and geographical; the scientific work was considered by chief scientist Wilson as the main work of the expedition: "No one can say that it will have only been a Pole-hunt ... We want the scientific work to make the bagging of the Pole merely an item in the results."[39] Wilson hoped to continue investigations, begun during the Discovery expedition, of the penguin colony at Cape Crozier,[40] and to fulfil a programme of geological, magnetic and meteorology studies on an "unprecedented" scale.[33] There were further plans to explore King Edward VII Land, a venture described by Campbell, who was to lead it, as "the thing of the whole expedition",[41] and Victoria Land.[33]

First season, 1910–11

The Terra Nova, photographed in December 1910 by Herbert Ponting

The Terra Nova, photographed in December 1910 by Herbert Ponting

Voyage out

Terra Nova sailed from Cardiff, Wales, on 15 June 1910.[42] Scott, detained by expedition business, sailed later on a faster passenger liner and joined the ship in South Africa.[43] In Melbourne, Australia, he left the ship to continue fund-raising, while Terra Nova proceeded to New Zealand.[44] Waiting for Scott in Melbourne was a telegram from Amundsen, informing Scott that the Norwegian was "proceeding south";[E] the telegram was the first indication to Scott that he was in a race. When asked by the press for a reaction, Scott replied that his plans would not change and that he would not sacrifice the expedition's scientific goals to win the race to the Pole.[44] In his diary he wrote that Amundsen had a fair chance of success, and perhaps deserved his luck if he got through.[45]

Scott rejoined the ship in New Zealand, where additional supplies were taken aboard, including 34 dogs, 19 Siberian ponies and three motorised sledges.[44] Terra Nova, heavily overladen, finally left Port Chalmers on 29 November 1910.[44] During the first days of December the ship was struck by a heavy storm; at one point, with the ship taking heavy seas and the pumps having failed, the crew had to bail her out with buckets.[46] The storm resulted in the loss of two ponies, a dog, 10 imperial tons (10,200 kg) of coal and 65 imperial gallons (300 L) of petrol.[47] On 10 December Terra Nova met the southern pack ice and was halted, remaining for 20 days before breaking clear and continuing southward. The delay, which Scott attributed to "sheer bad luck", had consumed 61 tons of coal.[48]

Cape Evans base

Inside Scott's Hut at Cape Evans (modern photograph)

Inside Scott's Hut at Cape Evans (modern photograph)

Arriving off Ross Island on 4 January 1911, Terra Nova scouted for possible landing sites around Cape Crozier at the eastern point of the island,[49][50] before proceeding to McMurdo Sound to its west, where both Discovery and Nimrod had previously landed. After Scott had considered various possible wintering spots, he chose a cape remembered from the Discovery days as the "Skuary",[51] about 15 miles (24 km) north of Scott's 1902 base at Hut Point.[48] Scott hoped that this location, which he renamed Cape Evans after his second-in-command,[51] would be free of ice in the short Antarctic summer, enabling the ship to come and go. As the seas to the south froze over, the expedition would have ready access over the ice to Hut Point and the Barrier.[52] At Cape Evans the shore parties disembarked, with the ponies, dogs, the three motorised sledges (one of which was lost during unloading),[53] and the bulk of the party's stores. Scott was "astonished at the strength of the ponies" as they transferred stores and materials from ship to shore.[54] A prefabricated accommodation hut, measuring 50 ft x 25 ft (15 m x 7.7 m), was erected and made habitable by 18 January.[55]

Amundsen's camp

Scott's programme included a plan to explore and carry out scientific work in King Edward VII Land, to the east of the Barrier. A party under Campbell was organised for this purpose, with the option of exploring Victoria Land to the north-west if King Edward VII Land proved inaccessible.[F] On 26 January 1911 Campbell's party left in the ship and headed east. After several failed attempts to land his party on the King Edward VII Land shore, Campbell exercised his option to sail to Victoria Land. On its return westward along the Barrier edge, Terra Nova encountered Amundsen's expedition camped in the Bay of Whales, an inlet in the Barrier.[56]

Amundsen was courteous and hospitable, willing for Campbell to camp nearby and offering him help with his dogs.[57] Campbell politely declined, and returned with his party to Cape Evans to report this development. Scott received the news on 22 February, during the first depot-laying expedition. According to Cherry-Garrard, the first reaction of Scott and his party was an urge to rush over to the Bay of Whales and "have it out" with Amundsen.[58] However, Scott recorded the event calmly in his journal. "One thing only fixes itself in my mind. The proper, as well as the wiser, course is for us to proceed exactly as though this had not happened. To go forward and do our best for the honour of our country without fear or panic."[59]

Depot laying, 1911

The aim of the first season's depot-laying was to place a series of depots on the Barrier from its edge (Safety Camp) down to 80° S, for use on the polar journey which would begin the following spring. The final depot would be the largest, and would be known as One Ton Depot. The work was to be carried out by 12 men, the 8 fittest ponies, and two dog teams; ice conditions prevented the use of the motor sledges.[60]

The journey started on 27 January, "in a state of hurry bordering on panic", according to Cherry-Garrard.[61] Progress was slower than expected, and the ponies' performance was adversely affected because the Norwegian snowshoes they needed for Barrier travel had been left behind at Cape Evans.[62] On 4 February the party established Corner Camp, 40 miles (64 km) from Hut Point, when a blizzard held them up for three days.[62] A few days later, after the march had resumed, Scott sent the three weakest ponies home (two died en route).[63] As the depot-laying party approached 80°, Scott became concerned that the remaining ponies would not make it back to base unless the party turned north immediately. Against the advice of Oates, who wanted to go forward, killing the ponies for meat as they collapsed, Scott decided to lay One Ton Depot at 79° 29′ S, more than 30 miles (48 km) north of its intended location.[63]

Scott returned to Safety Camp with the dogs, after risking his own life to rescue a dog-team that had fallen into a crevasse.[64] When the slower pony party arrived, one of the animals was in very poor condition and died shortly afterwards. Later, as the surviving ponies were crossing the sea ice near Hut Point, the ice broke up. Despite a determined rescue attempt, three more ponies died.[65] Of the eight ponies that had begun the depot-laying journey, only two returned home.[66]

Winter quarters, 1911

On 23 April 1911 the sun set for the duration of the winter months, and the party settled into the Cape Evans hut. Under Scott's naval regime the hut was divided by a wall made of packing cases, so that officers and men lived largely separate existences, scientists being deemed "officers" for this purpose.[67] Everybody was kept busy; scientific work continued, observations and measurements were taken, equipment was overhauled and adapted for future journeys. The surviving ponies needed daily exercise, and the dogs required regular attention.[68] Scott spent much time calculating sledging rations and weights for the forthcoming polar march.[69] The routine included regular lectures on a wide range of subjects: Ponting on Japan, Wilson on sketching, Oates on horse management and geologist Frank Debenham on volcanoes.[68][70] To ensure that physical fitness was maintained there were frequent games of football in the half-light outside the hut; Scott recorded that "Atkinson is by far the best player, but Hooper, P.O. Evans and Crean are also quite good."[71] The South Polar Times, which had been produced by Shackleton during the Discovery expedition, was resurrected under Cherry-Garrard's editorship.[68] On 6 June a feast was arranged, to mark Scott's 43rd birthday; a second celebration on 21 June marked Midwinter Day, the day that marks the midpoint of the long polar night.[72]

Main expedition journeys, 1911–12

Northern Party

After leaving news of Amundsen's arrival at Cape Evans, Campbell's Eastern party became the "Northern Party". On 9 February 1911 they sailed northwards, arriving at Robertson Bay, near Cape Adare on 17 February, where they built a hut close to Norwegian explorer Carstens Borchgrevink's old quarters.[73]

Borchgrevink's 1899 hut at Cape Adare (modern photograph). Campbell's Northern Party camped nearby in 1911–12.

Borchgrevink's 1899 hut at Cape Adare (modern photograph). Campbell's Northern Party camped nearby in 1911–12.

The Northern Party spent the 1911 winter in their hut. Their exploration plans for the summer of 1911–12 could not be fully carried out, partly due to the condition of the sea ice and also through their inability to discover a route into the interior. Terra Nova returned from New Zealand on 4 January 1912, and transferred the party to the vicinity of Evans Coves, a location approximately 250 miles (400 km) south of Cape Adare and 200 miles (320 km) northwest of Cape Evans. They were to be picked up on 18 February after the completion of further geological work,[74] but due to heavy pack ice, the ship was unable to reach them.[75] The group, with meagre rations which they had to supplement by fish and seal meat, were forced to spend the winter months of 1912 in a snow cave which they excavated on Inexpressible Island.[76] Here they suffered severe privations—frostbite, hunger, and dysentery, aggravated by extreme winds and low temperatures, and the discomfort of a blubber stove in confined quarters.[77]

On 17 April 1912 a party under Edward Atkinson, in command at Cape Evans during the absence of the polar party, went to relieve Campbell's party, but were beaten back by the weather.[78] The Northern Party survived the winter in their icy chamber, and set out for the base camp on 30 September 1912. Despite their physical weakness, the whole party managed to reach Cape Evans on 7 November, after a perilous journey which included a crossing of the difficult Drygalski Ice Tongue.[79] Geological and other specimens collected by the Northern Party were retrieved from Cape Adare and Evans Coves by Terra Nova in January 1913.[80]

Western geological parties

First geological expedition, January–March 1911

The objective of this journey was geological exploration of the coastal area west of McMurdo Sound, in a region between the McMurdo Dry Valleys and the Koettlitz Glacier.[81] This work was undertaken by a party consisting of Griffith Taylor, Debenham, Wright and P.O. Evans. They landed from Terra Nova on 26 January at Butter Point,[G] opposite Cape Evans on the Victoria Land shore. On 30 January, the party established its main depot in the Ferrar Glacier region, and then conducted explorations and survey work in the Dry Valley and Taylor Glacier areas before moving southwards to the Koettlitz Glacier. After further work there, they started homewards on 2 March, taking a southerly route to Hut Point, where they arrived on 14 March.[82]

Second geological expedition, November 1911 – February 1912

This was a continuation of the work carried out in the earlier expedition, this time centring on the Granite Harbour region approximately 50 miles (80 km) north of Butter Point.[83] Taylor's companions this time were Debenham, Gran and Forde. The main journey began on 14 November, and involved difficult travel over sea ice to Granite Harbour, which was reached on 26 November. Headquarters were established at a site christened Geology Point, and a stone hut was built. During the following weeks, exploration and surveying work took place on the Mackay Glacier, and a range of features to the north of the glacier were identified and named. The party was due to be picked up by Terra Nova on 15 January 1912, but the ship could not reach them. The party waited until 5 February before trekking southward, and were rescued from the ice when they were finally spotted from the ship on 18 February. Geological specimens from both Western Mountains expeditions were retrieved by Terra Nova in January 1913.[84]

Winter journey to Cape Crozier

This journey was the brainchild of Dr. Edward Wilson. He had suggested the need for it in the Zoology section of the Discovery Expedition's Scientific Reports, and was anxious to follow up this earlier research. The journey's scientific purpose was to secure Emperor Penguin eggs from the rookery near Cape Crozier at an early embryo stage, so that "particular points in the development of the bird could be worked out".[85] This required a trip in the depths of winter to obtain eggs in an appropriately early stage of incubation. A secondary purpose was to experiment with food rations and equipment in advance of the coming summer's polar journey.[86] Scott approved, and a party consisting of Wilson, Bowers and Cherry-Garrard set out on 27 June 1911.[87]

Two Emperor Penguins

Travelling during the Antarctic winter had not been previously tried; Scott wrote that it was "a bold venture, but the right men have gone to attempt it."[87] Cherry-Garrard later described the horrors of the 19 days it took to travel the 60 miles (97 km) to Cape Crozier. Gear, clothes, and sleeping bags were constantly iced up; on 5 July, the temperature fell below −77 °F (−60 °C) – "109 degrees of frost – as cold as anyone would want to endure in darkness and iced up clothes", wrote Cherry-Garrard. Often the daily distance travelled was little more than a single mile.[88]

At Cape Crozier the party, with great difficulty, built an igloo from snow blocks, stone, and a sheet of wood they had brought for the roof.[89] They were then able to visit the penguin colony and collect several Emperor Penguin eggs.[90] Subsequently their igloo shelter was almost destroyed in a blizzard with force 11 winds. The storm also carried away the tent upon which their survival would depend during their return journey, but fortunately this was recovered, half a mile away.[91] The group set out on the return journey to Cape Evans, arriving there on 1 August.[92] The three eggs that survived the journey went first to the Natural History Museum in South Kensington, and thereafter were the subject of a report from Dr. Cossar Stewart at the University of Edinburgh.[93] The eggs failed, however, to provide proof of Wilson's theories.[94]

Cherry-Garrard afterwards described this as the "worst journey in the world",[95] and used this as the title of the book that he wrote in 1922 as a record of the entire Terra Nova Expedition. Scott called the Winter Journey "a very wonderful performance",[92] and was highly satisfied with the experiments in rations and equipment: "We are as near perfection as experience can direct."[92]

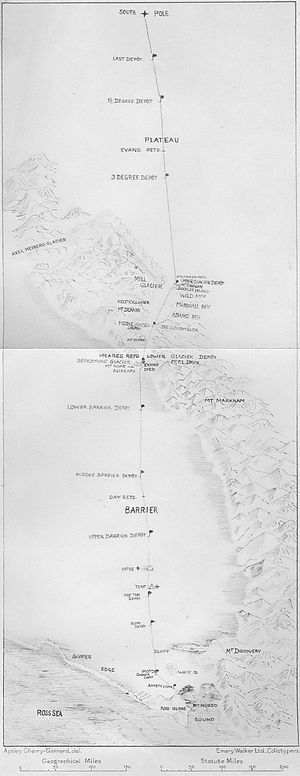

Map of route taken to the South Pole showing supply stops and significant events. Scott was found frozen to death with Wilson and Bowers, south of the One Ton Supply depot, in the spot marked "Tent" on the map.

Map of route taken to the South Pole showing supply stops and significant events. Scott was found frozen to death with Wilson and Bowers, south of the One Ton Supply depot, in the spot marked "Tent" on the map.

South polar journey

On 13 September 1911, Scott revealed his plans for the South Pole march. Sixteen men would set out, using motor-sledges, ponies and dogs for the Barrier stage of the journey, which would bring them to the Beardmore Glacier. At this point the dogs would return to base and the ponies would be shot for food. Thereafter, twelve men in three groups would ascend the glacier and begin the crossing of the polar plateau, using man-hauling. Only one of these groups would carry on to the pole; the supporting groups would be sent back at specified latitudes. The composition of the final polar group would be decided by Scott during the journey.[96]

The Motor Party (Lt. Evans, Day, Lashly and Hooper) started from Cape Evans on 24 October with two motor sledges, their objective being to haul loads to latitude 80° 30′ S and wait there for the others. By 1 November both motor sledges had failed after little more than 50 miles' travel, so the party man-hauled 740 pounds (336 kg) of supplies for the remaining 150 miles (241 km) reaching their assigned latitude two weeks later.[97] The other parties, which had left Cape Evans on 1 November with the dogs and ponies, caught up with them on 21 November.[98]

Scott's initial plan was that the dogs would return to base at this stage, and be kept there for possible use during the following season.[99] However, because of the slower than expected progress Scott decided to take the dogs on further.[100] Day and Hooper were despatched to Cape Evans with a message to this effect for Simpson, who had been left in charge there. On 4 December the expedition had reached the Gateway, the name given by Shackleton to the route from the Barrier on to the Beardmore Glacier. At this point a blizzard struck, forcing the men to camp until 9 December and to break into rations intended for the Glacier journey.[101] When the blizzard lifted, the remaining ponies, who were in an advanced state of exhaustion and could pull no further, were shot. On 11 December, Meares and Dimitri finally turned back with the dogs, carrying a message back to base that "things were not as rosy as they might be, but we keep our spirits up and say the luck must turn."[102]

The party began the ascent of the Beardmore, and on 20 December reached the beginning of the polar plateau where they laid the Upper Glacier Depot. There was still no hint from Scott as to who would be in the final polar party. On 22 December, at latitude 85° 20′ S, Scott sent back Atkinson, Cherry-Garrard, Wright and Keohane.[103] Scott gave Atkinson further verbal orders concerning the dogs; contradicting Scott's previous instructions, they were now to be brought out to meet and assist the polar party on its return journey the following March.[104]

The remaining eight men continued south, in better conditions which enabled them to make up some of the time lost on the Barrier. By 30 December they had "caught up" with Shackleton's 1908–09 timetable.[105] On 3 January 1912, at latitude 87° 32′ S, Scott made his decision on the composition of the polar party – five men (Scott, Wilson, Oates, Bowers and Edgar Evans) would go forward while Lt. Evans, Lashly and Crean would return. The decision to take five men forward involved recalculations of weights and rations, since everything had been based on four-men teams.[106]

Evans was given new and specific orders about the dogs, emphasising the need for them to be brought south to meet the polar party.[107] During his party's return journey Evans became seriously ill with scurvy. From One Ton Depot he could not march, and was carried on the sledge by his comrades to a point 35 miles (56 km) south of Hut Point.[108] On 18 February, Crean walked on alone to reach Hut Point, and by chance found Atkinson and Dimitri there with dog teams, preparing for a journey to resupply One Ton depot. A rescue party was formed, and Evans was brought to Hut Point, barely alive, on 22 February. In the confusion Scott's latest orders about the deployment of the dogs were overlooked.[109] Lashly and Crean were later each awarded Albert Medals for their life-saving efforts.[110]

Meanwhile the polar group continued towards the Pole, passing Shackleton's Furthest South (88° 23′ S) on 9 January. Seven days later, about 15 miles (24 km) from their goal, Amundsen's black flag was spotted and the party knew that they had been forestalled. They reached the Pole the next day, 17 January 1912, and discovered that Amundsen had arrived there on 14 December 1911. He had left a tent, some supplies, and a letter to King Haakon VII of Norway which he politely asked Scott to deliver.[111]

Scott and his men at Amundsen's base, Polheim, at the South Pole. Left to right: Scott, Bowers, Wilson, and PO Evans. Picture taken by Lawrence Oates.

Scott wrote in his diary: "The Pole. Yes, but under very different circumstances from those expected ... Great God! This is an awful place and terrible enough for us to have laboured to it without the reward of priority." He concluded the entry: "Now for a desperate struggle [to get the news through first]. I wonder if we can do it."[112]

After confirming their position and planting their flag, Scott's party turned homewards the next day. During the next three weeks good progress was made, Scott's diary recording several "excellent marches".[113] Nevertheless Scott began to worry about the physical condition of his party, particularly of Edgar Evans who was suffering from severe frostbite and was, Scott records, "a good deal run down."[114] The condition of Oates's feet became an increasing anxiety, as the group approached the summit of the Beardmore Glacier and prepared for the descent to the Barrier.[113] On 7 February, they began their descent, but were finding travel harder and had difficulty locating their depots. Despite this, Scott ordered a half-day's "geologising", and 30 pounds (14 kg) of samples were added to the sledges.[114] Edgar Evans's health was by now deteriorating rapidly; a hand injury was failing to heal, he was badly frostbitten, and is thought to have injured his head after several falls on the ice. "He is absolutely changed from his normal self-reliant self", wrote Scott.[114] All the party were suffering from malnutrition, but as the largest man, Evans felt this most. Near the bottom of the glacier he collapsed, and died on 17 February.[114]

On the Barrier stage of the homeward march the four survivors suffered from some of the most extreme weather conditions ever recorded in the region.[115] The weather, and the poor surfaces ("like pulling over desert sand" – Scott, 19 February)[116] slowed them down, as did Oates's worsening foot condition. Scott hoped for a change in the weather, but as February drew to a close the temperature fell further.[117] On 2 March, at the Middle Barrier Depot, Scott found a shortage of oil, apparently the result of evaporation: "With the most rigid economy it can scarce carry us to the next depot ... 71 miles away."[118] They found the same shortage at the next depot on 9 March, and no sign of "the dogs which would have been our salvation."[118] Daily marches were now down to less than five miles, and the party was desperately short of food and fuel. On or about 17 March, Oates, while apparently lucid, stepped outside the tent, saying, by Scott's account, "I am just going outside and I may be some time."[118] This sacrifice was not enough to save the others. Scott, Wilson and Bowers struggled on to a point 11 miles (18 km) south of One Ton Depot, but were halted on 20 March by a fierce blizzard. Although each day they attempted to advance, they were unable to do so, and their supplies ran out. Scott's last diary entry, dated 29 March 1912, the presumed date of their deaths, ends with these words:

Every day we have been ready to start for our depot 11 miles away, but outside the door of the tent it remains a scene of whirling drift. I do not think we can hope for any better things now. We shall stick it out to the end, but we are getting weaker, of course, and the end cannot be far. It seems a pity but I do not think I can write more. R. Scott. For God's sake look after our people.[118]Attempts to relieve the polar party, 1912

Re-supply of One Ton Depot

Scott had ordered the re-supply of One Ton Depot in instructions to Simpson immediately before setting out on the polar journey. These orders required the transportation to the depot of "five XS rations [an Extra Summit ration was food for four men for one week], or at all hazards three ... and as much dog food as could be carried, the depot to be laid by 10 January 1912".[119] When Atkinson returned to Cape Evans on 28 January, he learned that the minimum three rations had been deposited but that the requested dog food had not been taken. He decided to take the two outstanding rations to One Ton himself, but apparently took no action over the dog food.[120] Atkinson either overlooked or misunderstood Scott's instructions about bringing dogs south to meet and assist the returning polar party, because without dog food at One Ton Depot these orders could not possibly be carried out.[104]

The emergency that arose from Lt. Evans's rescue from the Barrier changed Atkinson's plans, and the role of completing the re-supply of One Ton fell to Cherry-Garrard, as the only "officer" available. He would be accompanied by the skilled dog driver Dimitri Gerov. Atkinson did not yet have fears for the polar party's safety, as Scott was not overdue and, when last seen on the Polar Plateau by Evans, had been travelling in good order and on schedule. Atkinson's verbal orders to Cherry-Garrard, remembered and recorded later, were "to travel to One Ton Depot as fast as possible and leave the food there. If Scott had not arrived before me, I was to judge what to do", and to "remember that Scott was not dependent on the dogs for his return, and that the dogs were not to be risked".[121]

Cherry-Garrard left Hut Point with Dimitri and two dog teams on 26 February, arriving at One Ton on 4 March and depositing the extra rations. Scott was not there. With supplies for themselves and the dogs for 24 days, they had about eight days' waiting time before having to return to Hut Point. The alternative to waiting was moving southwards, and in the absence of the dog food depot this would mean killing dogs for dog food as they went along, thus breaching Scott's "not to be risked" order (but within Cherry-Garrard's brief from Atkinson to "judge what to do"). However, Cherry-Garrard decided to wait for Scott. On 10 March, in worsening weather, with his own supplies dwindling and unaware that Scott's team were fighting for their lives less than 70 miles (110 km) away, Cherry-Garrard turned for home.[122] Atkinson would later write, "I am satisfied that no other officer of the expedition could have done better",[123] but Cherry-Garrard was troubled for the rest of his life by thoughts that he might have taken other actions that could have saved the polar party.[124]

Final relief effort

After Cherry-Garrard's return from One Ton Depot without news of Scott, anxieties slowly rose. Atkinson, now in charge at Cape Evans as the senior naval officer present,[H] decided to make an attempt to reach the polar party, and on 26 March set out with Keohane, man-hauling a sledge containing 18 days' provisions. In very low temperatures (−40 °F,−40 °C) they had reached Corner Camp by 30 March, when, in Atkinson's view, the weather, the cold and the time of year made further progress south impossible. Atkinson recorded, "In my own mind I was morally certain that the [polar] party had perished".[125]

Search party

The remaining expedition members (other than Campbell's Northern Party who were still away) waited at Cape Evans through the winter, continuing their scientific work. In the spring Atkinson had to consider whether efforts should first be directed to the rescue of Campbell's party, or to establishing if possible the fate of the polar party. A meeting of the whole group decided that they should first search for signs of Scott.[126] The search party set out on 29 October, accompanied by a team of mules that had been landed from the Terra Nova during its resupply visit the previous summer. On 12 November the party found the tent containing the frozen bodies of Scott, Wilson and Bowers, 11 miles (18 km) south of One Ton Depot. Atkinson read the relevant portions of Scott's diaries, and the nature of the disaster was revealed. After diaries, personal effects and records had been collected, the tent was collapsed over the bodies and a cairn of snow erected, topped by a cross fashioned from Gran's skis. The party searched further south for Oates's body, but found only his sleeping bag. On 15 November, they raised a cairn near to where they believed he had died.[127]

On returning to Hut Point on 25 November the search party found that Campbell's Northern Party had rescued itself and had returned safely to base.[127]

Aftermath

As Campbell was now the senior Naval officer of the expedition, he assumed command for its final weeks, until the arrival of Terra Nova on 18 January 1913. Before the final departure a large wooden cross was erected on the slopes of Observation Hill, overlooking Hut Point, inscribed with the five names of the dead and a quotation from Tennyson's Ulysses: "To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield".[128]

Given that the likely cause of the deaths of the polar party included starvation, scurvy, or both, the question of sledging diets is of interest. The rations carried and consumed by all the sledging parties on the expedition were based on nutritional science as understood in 1910, before knowledge of Vitamin C and its prevention of scurvy.[129] Emphasis was given to high protein content deemed necessary to replace calories burned during the heavy work of sledging, especially man-hauling. In fact, the caloric values of the rations were greatly over-estimated, although this was not apparent until many years later.[129] The staple daily ration per man was 16 ounces (450 g) biscuit, 12 ounces (340 g) pemmican, 3 ounces (85 g) sugar, 2 ounces (57 g) butter, 0.7 ounces (20 g) tea and 0.57 ounces (16 g) cocoa.[130] This diet would be supplemented on the Southern Journey by killing ponies for meat once their hauling function was over, but such supplements would not have bridged the calorie deficit for more than short periods.[129]

The loss of Scott and his party overshadowed all else in the public's mind, including Amundsen's feat in being first at the Pole.[131] For many years the image of Scott as a tragic hero, beyond reproach, remained virtually unchallenged, for although there were rifts among some who were close to the expedition, including relatives of those who died, this disharmony was not public. This image was reflected in a well-known 1948 film, Scott of the Antarctic, with John Mills in the title role and music by Ralph Vaughan Williams. There was no real change in public perceptions until the 1970s, by which time nearly all those directly concerned with the expedition were dead.[132]

Controversy was ignited with the publication of Roland Huntford's book Scott and Amundsen (1979, re-published and televised in 1985 as The Last Place on Earth). Huntford was critical of Scott's supposedly authoritarian leadership style and of his poor judgment of men, and blamed him for a series of organisational failures that led to the death of everyone in the polar party.[133] Scott's personal standing suffered from these attacks; efforts to restore his reputation have included the account by Ranulph Fiennes (a direct rebuttal of Huntford's version), Susan Solomon's scientific analysis of the weather conditions that ultimately defeated Scott, and David Cranes's 2005 biography of Scott, the last, according to historian Stephanie Barczewski, doing "a tremendous job of restoring Scott's humanity."[134]

In comparing the achievements of Scott and Amundsen, most polar historians generally accept that Amundsen's skills with ski and dogs, and his general familiarity with ice conditions, gave him considerable advantages in the race for the Pole.[135] Scott's verdict on the disaster that overtook his party, written when he was close to death in extreme conditions, blames a long list of misfortunes rather than faulty organisation.[136] While detractors such as Huntford reject this as self-justifying,[137] Cherry-Garrard observes that "the whole business simply bristles with 'ifs'"; an accumulation of decisions and circumstances that might have fallen differently ultimately led to catastrophe. But "we were as wise as anyone can be before the event."[138] Diana Preston's verdict, after summarising all the circumstances of the southern journey, is: "The point is not that they ultimately failed but that they so very nearly succeeded."[139] The story received important fictional treatment in Beryl Bainbridge's Booker Prize short-listed novel, The Birthday Boys, which tells sections of the story from the perspectives in turn of Edgar Evans, Edward Wilson, Robert Falcon Scott, Henry Robertson Bowers, and Lawrence Oates.

See also

- Comparison of Amundsen's South Pole expedition and the simultaneous Terra Nova expedition of Scott

- Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration

- List of Antarctic expeditions

Notes and references

Notes

- ^ The latitude of 82° 17′ was accepted at the time. However, modern maps and a re-examination of photographs and drawings have indicated that the final position was probably about 82° 11′. (Crane, pp. 214–15).

- ^ The Discovery veterans were Scott, Wilson, Edgar Evans, Lashly, Crean and Wiliamson. The Nimrod veterans were Priestley, Day, Cheetham, Paton and Williams (list of Nimrod personnel in Shackleton, The Heart of the Antarctic, pp. 17–18).

- ^ During the early, depot-laying stages of the expedition, Scott expresses loss of faith in the dogs (Huxley, Scott's Last Expedition, Vol. I, p. 205). In his later diary entries covering the Southern Journey their performance is described as "splendid" (Huxley, Scott's Last Expedition, Vol. I, p. 486).

- ^ The total cost of the expedition was not published. One of Scott's last letters was to Sir Edgar Speyer, the expedition's treasurer; in it, Scott apologises for leaving the finances in "a muddle". (Huxley, Scott's Last Expedition, Vol. I, p. 600).

- ^ The telegram's exact wording is uncertain. Cherry-Garrard, p. 82, Crane, p. 423, and Preston, p. 127, all report it as a simple, "Am going south". Solomon, p. 64, gives a longer version: "Beg leave to inform you Fram proceeding Antarctica"; Fiennes and Huntford both use this form.

- ^ Scott's orders to Campbell (Huxley, Scott's Last Expedition, Vol. II, pp. 79–82); the party was then called the "Eastern Party".

- ^ Butter Point was named after a depot containing butter was left there during the Discovery expedition. (Huxley, Scott's Last Expedition, Vol. II, p. 183).

- ^ Lt. Evans had departed with the Terra Nova in March 1912. (Crane, p. 556).

References

- ^ Crane, pp. 332, 335–43.

- ^ Huntford, pp. 176–77.

- ^ Preston, pp. 100–01.

- ^ Crane, pp. 335–36.

- ^ Riffenburgh, pp. 110–16.

- ^ Huxley, p. 179.

- ^ Crane, p. 430.

- ^ Huxley, pp. 186–87.

- ^ Fiennes, p. 157.

- ^ Crane, p. 425.

- ^ Listed in Huxley, Scott's Last Expedition, Vol. I, pp. xxi–xxii.

- ^ Huxley, Scott's Last Expedition, Vol. II, p. 498.

- ^ Crane, pp. 401–03.

- ^ a b c d Crane, pp. 413–16.

- ^ Huntford, p. 267.

- ^ Preston, p. 111.

- ^ a b Measuring Worth.

- ^ Limb & Cordingley, p. 94.

- ^ a b Preston, p. 112.

- ^ Crane, p. 417.

- ^ Preston, p. 114.

- ^ Huntford, pp. 262–64.

- ^ Crane, p. 432.

- ^ Preston, p. 101.

- ^ Preston, pp. 112–13.

- ^ Preston, pp. 113 and 217.

- ^ Huntford, p. 255.

- ^ Preston, p. 89.

- ^ Solomon, p. 22.

- ^ Crane, pp. 462–64.

- ^ Preston, p. 50.

- ^ Huxley, Scott's Last Expedition, Vol. I, p. 432.

- ^ a b c d Crane, p. 397.

- ^ a b Crane, p. 401.

- ^ See Huxley, Scott's Last Expedition, Vol. II, pp. 488–89.

- ^ Huxley, Scott of the Antarctic, pp. 183, 192–93.

- ^ Crane, p. 277.

- ^ Crane, p. 406.

- ^ Edward Wilson letter, quoted in Crane, p. 398.

- ^ Seaver, pp. 127–34.

- ^ Crane, p. 474.

- ^ Crane, p. 409.

- ^ Crane, p. 411.

- ^ a b c d Preston, pp. 128–31.

- ^ Crane, p. 424.

- ^ Huxley, Scott's Last Expedition, Vol. I, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Huxley, Scott's Last Expedition, Vol. I, p. 16.

- ^ a b Preston, p. 137.

- ^ Huxley, L. (ed.), pp. 81–85.

- ^ Crane, pp. 448–50.

- ^ a b Huxley, Scott's Last Expedition, Vol. I, pp. 89–90.

- ^ Crane, p. 450.

- ^ Huxley, L. (ed.), pp. 106–07.

- ^ Huxley, L. (ed.), p. 99.

- ^ Preston, p. 139.

- ^ Crane, pp. 473–74.

- ^ Preston, p. 144.

- ^ Cherry-Garrard, p. 172.

- ^ Huxley, L. (ed.), pp. 187–88.

- ^ Fiennes, p. 206.

- ^ Cherry-Garrard, p. 147.

- ^ a b Preston, pp. 214–16.

- ^ a b Preston, p. 142.

- ^ Cherry-Garrard, pp. 167–70. Wilson thought it an "insane risk" – Preston, p. 144.

- ^ Bowers's account of the incident, Cherry-Garrard, pp. 182–196.

- ^ Cherry-Garrard, p. 201.

- ^ Preston, p. 149.

- ^ a b c Preston, p. 151.

- ^ Preston, p. 158.

- ^ Huxley, L. (ed.), pp. 292–94, p. 316.

- ^ Huxley, L. (ed.), p. 259.

- ^ Huxley, L. (ed.), pp. 304–05, pp. 324–28.

- ^ Huxley, Scott's Last Expedition, Vol. II, pp. 87–90.

- ^ Huxley, L. (ed.), p. 112.

- ^ Huxley, L. (ed.), p. 126.

- ^ Huxley, Scott's Last Expedition, Vol. II, p. 130.

- ^ Huxley, L. (ed.), pp. 134–35.

- ^ Huxley, Scott's Last Expedition, Vol. II, pp. 312–16.

- ^ Huxley, Scott's Last Expedition, Vol. II, pp. 155–79.

- ^ Huxley, L. (ed.), pp. 401–02.

- ^ See Scott's instructions, Huxley, Scott's Last Expedition, Vol. II, pp. 184–85.

- ^ Huxley, Scott's Last Expedition, Vol. II, pp. 186–221.

- ^ Scott's instructions; Huxley, Scott's Last Expedition, Vol. II, pp. 222–23.

- ^ Huxley, Scott's Last Expedition, Vol. II, pp. 224–290.

- ^ Huxley, Scott's Last Expedition, Vol. II, p. 1.

- ^ Cherry-Garrard, pp. 305–07.

- ^ a b Huxley, Scott's Last Expedition, Vol. I, pp. 333–34.

- ^ Cherry-Garrard, pp. 295–309.

- ^ Cherry-Garrard, pp. 310–12.

- ^ Cherry-Garrard, pp. 316–22.

- ^ Cherry-Garrard, pp. 323–335.

- ^ a b c Huxley, Scott's Last Expedition, Vol. I, pp. 361–69.

- ^ Cherry-Garrard, pp. 351–53.

- ^ Fiennes, p. 260.

- ^ Cherry-Garrard, p. 350.

- ^ Preston, pp. 158–59.

- ^ Preston, pp. 163–65.

- ^ Huxley, Scott's Last Expedition, Vol. I, p. 470.

- ^ Huxley, Scott's Last Expedition, Vol. II, pp. 298–306.

- ^ Fiennes, p. 275.

- ^ Preston, pp. 167–68.

- ^ Huxley, Scott's Last Expedition, Vol. I, p. 496.

- ^ Crane, p. 530.

- ^ a b Cherry-Garrard, p. 439.

- ^ Crane, p. 534.

- ^ Crane, p. 536.

- ^ Preston, p. 180.

- ^ Lashly's diary, quoted in Cherry-Garrard, pp. 442–62.

- ^ Preston, pp. 206–08.

- ^ Huxley, Scott of the Antarctic, pp. 275 and 278.

- ^ Huxley, Scott's Last Expedition, Vol. I, pp. 529–45.

- ^ Huxley, Scott's Last Expedition, Vol. I, p. 545. The words "to get the news through first" were omitted for Scott's published diary. Huntford, p. 481.

- ^ a b Huxley, Scott's Last Expedition, Vol. I, pp. 547–62.

- ^ a b c d Crane, pp. 547–52.

- ^ Solomon, pp. 292–94.

- ^ Huxley, Scott's Last Expedition, Vol. I, p. 575.

- ^ Preston, p. 199.

- ^ a b c d Huxley, Scott's Last Expedition, Vol. I, pp. 583–95.

- ^ Cherry-Garrard, pp. 30–32.

- ^ Cherry-Garrard, pp. 468–69.

- ^ Cherry-Garrard, pp. 472–73.

- ^ Huntford, p. 504.

- ^ Huxley, Scott's Last Expedition, Vol. II, p. 306.

- ^ Preston, p. 210.

- ^ Huxley, Scott's Last Expedition, Vol. II, p. 309.

- ^ Preston, p. 211.

- ^ a b Huxley, Scott's Last Expedition, Vol. II, pp. 338–49.

- ^ Preston, p. 229.

- ^ a b c Preston, pp. 218–19.

- ^ Preston, p. 181.

- ^ Huntford, p. 526.

- ^ Fiennes, pp. 410–22.

- ^ Barczewski, pp. 252–60.

- ^ Barczewski, pp. 305–08.

- ^ Crane, p. 426; Preston, p. 221.

- ^ Preston, pp. 214–15.

- ^ Huntford, p. 509.

- ^ Cherry-Garrard, pp. 609–10.

- ^ Preston, p. 228.

Sources

- Barczewski, Stephanie (2007). Antarctic Destinies: Scott, Shackleton and the changing face of heroism. London: Hambledon Continuum. ISBN 978-1-84725-192-3.

- Cherry-Garrard, Apsley (1970) [1922]. The Worst Journey in the World. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-009501-2. OCLC 16589938.

- Crane, David (2005). Scott of the Antarctic: A Life of Courage, and Tragedy in the Extreme South. London: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-00-715068-7. OCLC 60793758.

- Fiennes, Ranulph (2003). Captain Scott. Hodder & Stoughton Ltd. ISBN 0-340-82697-5.

- Huntford, Roland (1985). The Last Place On Earth. London: Pan Books. ISBN 0-330-28816-4.

- Huxley, Elspeth (1977). Scott of the Antarctic. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 0-297-77433-6.

- Huxley, Leonard, ed (1913). Scott's Last Expedition, Volume I: Being the Journals of Captain R.F. Scott, R.N., C.V.O.. London: Smith, Elder & Co. OCLC 1522514.

- Huxley, Leonard, ed (1913). Scott's Last Expedition, Volume II: Being the reports of the journeys and the scientific work undertaken by Dr. E.A. Wilson and the surviving members of the expedition. London: Smith, Elder & Co. OCLC 1522514.

- Limb, Sue; Cordingley, Patrick (1982). Captain Oates, Soldier and Explorer. London: B.T. Batsford. ISBN 0-7134-2693-4.

- Preston, Diana (1999). A First Rate Tragedy: Captain Scott's Antarctic Expeditions (paperback ed.). London: Constable. ISBN 0-09-479530-4. OCLC 59395617.

- Riffenburgh, Beau (2005). Nimrod. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 0-7475-7253-4.

- Seaver, George (1933). Edward Wilson of the Antarctic. London: John Murray.

- Shackleton, Ernest (1911). The Heart of the Antarctic. London: William Heinemann.

- Solomon, Susan (2001). The Coldest March: Scott's Fatal Antarctic Expedition. New Haven (US): Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-09921-5.

- "Purchasing Power of British Pounds from 1264 to Present". MeasuringWorth. http://www.measuringworth.com/ppoweruk/. Retrieved 2011-10-12.

Further reading

- Bainbridge, Beryl (1991). The Birthday Boys. Duckworth. ISBN 0-715623788.

- Fiennes, Ranulph (2005). Race to the Pole: Tragedy, Heroism, and Scott's Antarctic Quest. Hyperion. ISBN 1-4013-0047-2.

- Hattersley-Smith, G., ed (1984). The Norwegian with Scott: The Antarctic Diary of Tryggve Gran 1910–13. HMSO. ISBN 0-11-290382-7.

- Jones, Max (2003). The Last Great Quest: Captain Scott's Antarctic Sacrifice. OUP. ISBN 0-19-280483-9.

- Lambert, K. (2001). The Longest Winter: The Incredible Survival of Captain Scott's Lost Party. Smithsonian Books. ISBN 1-58834-195-X.

- Ponting, H G (1921). The Great White South. Duckworth.

External links

- South-pole.com

- Coolantarctica.com

- The Antarctic Circle website and forum

- The Antarctic Heritage Trust

- Herbert Ponting Photographs

- Herbert G Ponting's Haunting Expedition Record — slideshow by The First Post

- Project Gutenberg: The Worst Journey in the World by Apsley Cherry-Garrard

- Scott Polar Research Institute daily blog of Scott's Journal

Categories:- 1910 in the United Kingdom

- 1910 in Antarctica

- 1911 in Antarctica

- 1912 in Antarctica

- 1913 in Antarctica

- Antarctic expeditions

- Antarctic expedition deaths

- Heroic Era of Antarctic exploration

- United Kingdom and the Antarctic

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.