- McMurdo Sound

-

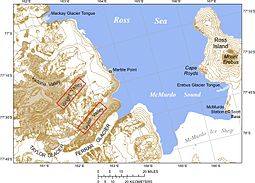

The ice-clogged waters of Antarctica's McMurdo Sound extend about 55 km (35 mi) long and wide. The sound opens into the Ross Sea to the north. The Royal Society Range rises from sea level to 13,205 feet (4,205 m) on the western shoreline. The nearby McMurdo Ice Shelf scribes McMurdo Sound's southern boundary. Ross Island, an historic jumping-off point for polar explorers, designates the eastern boundary. The active volcano Mt Erebus at 12,448 feet (3,794 m) dominates Ross Island. Antarctica's largest science base, the United States' McMurdo Station, as well as New Zealand’s Scott Base are located on the island’s south shore. Less than 10 percent of McMurdo Sound's shoreline is ice-free.[1]

Captain James Clark Ross discovered the sound, which is about 800 miles (1,300 km) from the South Pole, in February 1841 and named it after Lt. Archibald McMurdo of HMS Terror.[2] The sound today serves as a re-supply route for cargo vessels and for aircraft that land upon floating ice airstrips near McMurdo Station. However, McMurdo Station’s continuous occupation by scientists and support staff since 1957-58 has turned Winter Quarters Bay into a markedly polluted harbor.

The pack ice that girdles the shoreline at Winter Quarters Bay and elsewhere in the sound presents a formidable obstacle to surface ships. Vessels require ice-strengthened hulls and often have to rely upon icebreaker escorts. Such extreme sea conditions have limited access by tourists, who otherwise are appearing in increasing numbers in the open waters of the Antarctica Peninsula. The few tourists who reach the McMurdo Sound find a spectacular scenery with wildlife viewing ranging from killer whales, seals, to adelie and emperor penguins.

Cold circumpolar currents of the Southern Ocean reduce the flow of warm South Pacific or South Atlantic waters reaching McMurdo Sound and other Antarctic coastal waters. Bitter katabatic winds spilling down from the Antarctica's polar plateau into McMurdo Sound underscore Antarctica's status as the coldest and windiest continent in the world. The sound freezes over with sea ice approximately 10 feet (3.0 m) thick during winter. The austral summer causes the pack ice to break up. Wind and currents may push the ice northward into the Ross Sea, stirring up cold bottom currents that spill into the ocean basins of the world. Temperatures during the dark winter months at McMurdo Station have dropped as low as −59 °F (−51 °C). December and January are the warmest months, with average highs at 30 °F (−1 °C) and 31 °F (−1 °C) respectively (USA Today).

Contents

Ice defines strategic role

McMurdo Sound's role as a strategic waterway dates back to early 20th century Antarctic exploration. British explorers Ernest Shackleton and Robert Scott built bases on the sound's shoreline as jumping-off points for their overland expeditions to the South Pole.

McMurdo Sound's logistic importance continues today. Aircraft transporting cargo and passengers land upon frozen runways at Williams Field located on the McMurdo Ice Shelf. Moreover the annual sealift of a cargo ship and fuel tanker rely upon the sound as a supply route to the continent's largest base at McMurdo Station. Both the U.S. base and New Zealand's nearby Scott Base are located on the southern tip of Ross Island.

Ross Island is the farthest-south land in Antarctica accessible by ship. In addition the harbor at McMurdo's Winter Quarters Bay is the world's southernmost seaport (Department of Geography, Texas A&M University). Ship access, however, depends upon favorable ice conditions.

McMurdo Sound during austral winter presents a virtually impenetrable expanse of surface ice. Even during summer, ships approaching McMurdo Sound are often blocked by various concentrations of first-year ice, fast ice (connected to the shoreline), and hard multi-year ice. Subsequently, icebreakers are required for maritime re-supply missions to McMurdo Station. Nonetheless, ocean currents and fierce Antarctic winds can drive pack ice north into the Ross Sea, temporarily producing areas of open water.

Iceberg B-15A clogs McMurdo Sound

An iceberg that calved off Iceberg B-15 caused extensive pack ice buildup in McMurdo Sound, blocking shipping and preventing penguin access to open water.

An iceberg that calved off Iceberg B-15 caused extensive pack ice buildup in McMurdo Sound, blocking shipping and preventing penguin access to open water.

A common event of previously unseen dimensions occurred on the Ross Ice Shelf in 2000 that wreaked havoc at McMurdo Sound more than five years later. The 175-mile (282 km)-long Iceberg B-15, the largest ever seen at the time, broke off from the Ross Ice Shelf in March 2000 (Antarctic Climate & Ecosystems: Cooperative Research Center). Then, on October 27, 2005, B-15 suddenly broke up.

Research based upon measurements retrieved from a seismometer previously placed on B15 indicated that ocean swells caused by an earthquake in 8,000 miles (13,000 km) away in the Gulf of Alaska caused the breakup, according to a report by the U.S. National Public Radio.[3] Wind and sea currents shifted a smaller but still massive Iceberg B-15A towards McMurdo Sound. B-15A's enormous girth temporarily blocked the outflow of pack ice from McMurdo Sound, according to news reports.

Iceberg B-15A's grounding at the mouth of McMurdo Sound also blocked the path for thousands of penguins to reach their food source in open water. Moreover, pack ice built up behind the iceberg in the Ross Sea creating a nearly 80-nautical-mile (150 km) frozen barrier that blocked two cargo ships enroute to re-supply McMurdo Station, according to the U.S. National Science Foundation.

The icebreaker USCGC Polar Star and the Russian Krasin were required to open a ship channel through ice up to 10 feet (3.0 m) thick. The last leg of the channel followed a route along the eastern shoreline of McMurdo Sound adjacent to Ross Island. The icebreakers escorted the tanker USNS Paul Buck to McMurdo Station's ice pier in late January. The freighter MV American Tern followed on February 3.

Similar pack ice blocked a National Geographic expedition aboard the 110-foot (34 m) Braveheart from reaching B-15A. However, expedition divers were able to explore the underwater world of another grounded tabular iceberg. They encountered a surprising environment of fish and other sea life secreted within a deep iceberg crevasse. Discoveries included starfish, crabs, and ice fish. The latter were found to have burrowed thumb-sized holes into the ice.

The expedition reported an exceedingly rare and seldom witnessed occurrence of an iceberg exploding. Shards of ice erupted into the air as if a bomb went off, this only hours after divers surfaced and after the Braveheart moved away from the iceberg (National Geographic).[4]

Winds have far reaching effects

Polar winds are a driving force behind weather systems arising from three surface zones that converge at McMurdo Sound: the polar plateau and Transantarctic Mountains, the Ross Ice Shelf, and the Ross Sea. These surface zones create a range of dynamic weather systems. Cold, heavy air descending rapidly from the polar plateau at elevations of 10,000 feet (3,000 m) or more spawns fierce katabatic winds. These dry winds can reach hurricane force by the time they reach the Antarctic coast. Wind instruments recorded Antarctica’s highest wind velocity at the coastal station Dumont d'Urville in July 1972 at 199 mph (320 km/h) or 327 km/h (Australian Government Antarctica Division).

Prevailing winds spilling into McMurdo Sound shoot between mountain passes and other land formations, stirring up blizzards known locally as “Herbies.” Such blizzards can occur any time of year. Residents of McMurdo Station and Scott Base have dubbed the nearby White Island and Black Island as Herbie Alley due to winds that funnel blizzards between the islands (Field Manual for the U.S. Antarctic Program).

Overall the continent’s extreme cold air scarcely holds enough moisture for snowfall. Consequently, Antarctica’s blizzards are at times as much about wind stirring up existing snow as they are about new snowfall. For instance, the water equivalent from annual snow fall on Ross Island averages only 17.6 centimeters (National Science Foundation). Snowfall in Antarctica’s interior is far less at 2 inches (5 centimeters). Noted as well are the McMurdo Dry Valleys on the western shores of McMurdo Sound where snow seldom accumulates.

Antarctica's shortfall in new snow does not lessen the continent's striking polar climate. Antarctica essentially doubles in size during the winter as the surrounding sea water freezes (Antarctic Connection). The subsequent annual summer melt of the estimated 7,000,000 square miles (18,000,000 km2) of ice that rings Antarctica creates the planet’s largest seasonal climate event (USA Today). The result is a vertical circulation driven by a massive heat and energy exchange between ice, ocean, and atmosphere.

McMurdo Sound provides an important component in Antarctica’s global effects upon climate. A key factor is the polar winds that can drive the sound’s pack ice into the Ross Sea summer or winter. Frigid katabatic winds rake subsequent exposed water causing sea ice to form. Freezing surface water excludes salt from the water below; leaving behind heavy, cold water that sinks to the ocean floor. This process repeats itself along Antarctica’s coastal areas, spreading cold sea water outward into the world’s ocean basins (Australian Government Antarctic Division).

According to an interview with a climatologist Gerd Wendler published in the National Science Foundation’s Antarctic Sun, one could dive to the ocean floor anywhere in the world and encounter water from the coast of Antarctica. "Seventy five percent of all the bottom water, wherever you are, comes from Antarctica."

McMurdo Station

- Average mean sea-level temp: −20 °C

- Monthly mean range: −3 °C in January to −28 °C in August

- Stormiest months: February and October

Source: U.S. National Science Foundation.

Antarctica

- Coldest, highest, windiest continent in the world.

- Highest recorded wind velocity: 199 mph (327 km/h), Dumont d'Urville, July 1972.

Source: Australian Government Antarctica Division.

Life below the ice

A rich sea life thrives under the barren expanse of McMurdo Sound’s ice pack. For example, frigid waters that would kill many other fish in the world sustain the Antarctic notothenioids, a bony "ice fish" related to walleyes and perch. The notothenioids feature an Antifreeze protein in their bloodstream that prevents them from freezing. Notothenioids account for more than 50 percent of the number of fish species in the Antarctic coastal regions and 90 to 95 percent of the biomass, according to the National Academy of Sciences for the United States.

What some sea creatures lack in numbers, they make up for in their visual presentation. McMurdo Sound divers encounter colorful examples of sea life, including bright yellow cactus sponges and green globe sponges. The starfish, sea urchin, and the sea anemone are also present. The latter is noted for its wispy tentacles. Large sea spiders inhabit the deeps of the sound and feed on sea anemone, whereas swarms of Antarctic krill flourish in the upper depths of the icy waters. The shrimp-like krill is a key species in the Southern Ocean food chain for sea life ranging from the baleen whale to penguins. The sound is also home to soft coral, whose flexible form allows the creature to bend so as to feed off the ocean floor, according to the “Underwater Field Guide to Ross Island & McMurdo Sound.”

Antarctic penguins, famous for their waddling walk on surface ice, transform themselves into graceful and powerful swimmers underwater. The Emperor Penguins’ pursuit of squid, fish, and crustaceans leads them to dive as deep as 500 meters. However, the Emperor can go deeper. Scientists have found that the penguin can reach 600 meters for short durations. The much smaller Adelie Penguin is less ambitious. It feeds underwater for up to two minutes at a maximum depth of 170 meters (Underwater Field Guide to Ross Island & McMurdo Sound).

The Weddell Seal out-dives even the Emperor Penguin. The seal can hold its breath for up to 80 minutes and reach a depth of 700 meters (Underwater Field Guide to Ross Island & McMurdo Sound). Scientists diving in McMurdo also encounter the Leopard Seal, and Crabeater Seal. The many-storied Leopard seal is a ferocious predator that preys on warm-blooded animals, such as other seals and penguins, whereas the more sedate crabeater uses its unusual multilobed teeth to sieve krill from the water.

Seals have a natural enemy in the orca or Killer Whale of McMurdo Sound. The killer whale's voracious appetite leads it to consume up to 500 lb. (227 kg) of food daily. The orcas feature black and white coloring, a large dorsal fin (up to 1.8 m), and enormous strength and size (males can be eight m). The whales travel in pods of up to 30 individuals and can swim up to 46 kilometers/hour or 29 miles/h. (“Underwater Field Guide to Ross Island & McMurdo Sound.”)

Seascape reveals human impact

More than 50 years of continuous operation of the United States and New Zealand bases on Ross Island have left pockets of severe pollution marring McMurdo Sound’s pristine environment. Until 1981, McMurdo Station residents simply towed their garbage out to the sea ice and let nature take its course. The garbage sunk to the sea floor when the ice broke up in the spring, according to news reports.[5]

A 2001 survey of the seabed near McMurdo revealed 15 vehicles, 26 shipping containers, and 603 fuel drums, as well as some 1,000 miscellaneous items dumped on an area of some 50 acres (20 hectares). Findings by scuba divers were reported in the State of the Environment Report, a New Zealand sponsored study.[6][7]

The study by the government agency Antarctica New Zealand revealed that decades of daily pumping thousands of gallons of raw sewage from 1,200 summer residents into the sound had fouled Winter Quarters Bay, the harbor at McMurdo. The pollution ended in 2003 when a $5 million waste treatment plant went online.[8] Other documented bay water contaminants include leakage from an open dump at the station. The dump introduced heavy metals, petroleum compounds, and chemicals into the water.[7]

Zoologist Clive Evans from Auckland University described McMurdo's harbor as "one of the most polluted harbors in the world in terms of oil", according to a 2004 article by the New Zealand Herald.

Modern operations in McMurdo Sound have sparked surface cleanup efforts, re-cycling, and exporting trash and other contaminates by ship. The U.S. National Science Foundation began a 5-year, $30-million cleanup program in 1989, according to Reuters News Agency.[9] The concentrated effort targeted the open dump at McMurdo. By 2003, the U.S. Antarctic Program reported recycling approximately 70% of its wastes, according to Australia’s Herald Sun.

The 1989 cleanup included workers testing hundreds of barrels at the dump site, mostly full of fuels and human waste, for identification prior to being loaded onto a freighter for exportation. The precedent for exporting wastes began in 1971. The United States shipped out tons of radiation-contaminated soil after officials shut down a small nuclear power plant.[10]

The Erebus Ice Tongue is located near the ship channel used during annual re-supply missions to McMurdo Station. NASA false-color, composite satellite image.

The Erebus Ice Tongue is located near the ship channel used during annual re-supply missions to McMurdo Station. NASA false-color, composite satellite image.

Yet the very ships involved in supporting the export of McMurdo Station’s waste present pollution hazards themselves. A study by the Australian Institute of Marine Science found that anti-fouling paints on the hulls of icebreakers are polluting McMurdo Sound.[11] Such paints kill algae, barnacles, and other marine life that adhere to ship hulls. Scientists found that samples taken from the ocean floor contained high levels of tributyltin (TBT), a component of the anti-fouling paints. “The levels are close to the maximum, you will find anywhere, apart from ship grounding sites", said Andrew Negri of the institute.

Ships, aircraft, and land-based operations in McMurdo Sound all present hazards of oil spills or fuel leaks. For instance, in 2003, the build-up of two years of difficult ice conditions blocked the U.S. tanker MV Richard G. Matthiesen from reaching the harbor at McMurdo Station, despite the assistance of icebreakers. Instead shore workers rigged a temporary 3.5-mile (5.6 km) fuel line over the ice pack to discharge the ship’s cargo. The ship pumped more than 6 million gallons of fuel to storage facilities at McMurdo.[12]

Officials balance the potential for fuel spills inherent in such operations against the critical need to re-supply McMurdo Station. A fuel tank spill in an unrelated on-shore incident in 2003 spilled roughly 6,500 gallons of diesel fuel at a McMurdo Station helicopter pad.[13] The 1989 grounding of the Argentine ship Bahia Paraiso and subsequent spillage of 170,000 gallons of oil into the sea near the Antarctic Peninsula graphically illustrated environmental hazards inherent in Antarctic re-supply missions.[5]

Tourism surge yet to reach McMurdo

Antarctica’s extreme remoteness and hazardous travel conditions limit Antarctica tourism to an expensive niche industry largely centered on the Antarctic Peninsula. The number of seaborne tourists grew fourfold during the 1990s – reaching more than 14,000 by 2000, up from 2,500 ten years earlier.[14] More than 46,000 airborne and seaborne tourists visited Antarctica during the 2007-2008 season, according to the International Association of Antarctic Tour Operators (IAATO).[15]

This confederation of tour operators reports that only 5% of Antarctic tourists visit the Ross Sea area, which encompasses McMurdo Sound. Tourists congregate on the ice-free coastal zones during summer near the Antarctic Peninsula. The peninsula’s wildlife, soaring mountains, and dramatic seascapes have drawn commercial visitors since the late 1950s, when Argentina and Chile operated cruises to the South Shetland Islands (Science and Stewardship in the Antarctic: Commission on Geosciences, Environment, and Resources. 1993).

Tourists flights began in 1957, when a Pan American Boeing 377 Stratocruiser made the first civilian flight to Antarctica. Commercial flights landed at McMurdo Sound and the South Pole in the 1960s. Routine over-flights from Australia and New Zealand took place between 1977 and 1980, transporting more than 11,000 passengers, according to New Zealand Antarctica, which manages Scott Base. One such flight, Air New Zealand Flight 901, crashed into Mount Erebus on the eastern shores of McMurdo Sound. The crash high on the slopes of the active volcano took the lives of all 257 people aboard the aircraft.

In 1969 the MS Explorer brought sea going tourists to Antarctica (British Antarctic Survey). The cruise’s founder, Lars-Eric Lindblad, coupled expeditionary cruising with education. He is quoted as saying, “You can’t protect what you don’t know” (IAATO). In the decades since the Lindblad, ships engaged in Antarctic sight-seeing cruises have grown in size and number.

Infrequent Antarctic cruises have included passenger vessels carrying up to 960 tourists (IAATO). Such vessels may conduct so-called “drive-by” cruises with no landings made ashore. Moreover, the Russian Kapitan Khlebnikov (icebreaker) has conducted voyages to the Weddell Sea and Ross Sea regions since 1992. High-latitude cruises in dense pack ice are only achievable during the summer season, November into March. In 1997, the vessel Kapitan Khlebnikov claimed the distinction of being the first ship to circumnavigate Antarctica with passengers (Quark Expeditions). Passengers aboard the icebreaker make landings aboard inflatable zodiacs to explore remote beaches. Their itinerary may also include stops at Ross Island's historic explorer huts at Discovery Point near McMurdo Station or Cape Royds (Antarctica New Zealand).

Additionally, the Russian icebreaker extends the reach of tourism by launching helicopter trips from its decks, including visits to sites such as the McMurdo Dry Valleys and areas noted for wildlife viewing. However, the International Association of Tour Operators (IAATO) has established voluntary standards to discourage tourists from disrupting wildlife. Nonetheless, large ships, carrying more than 400 passengers, may spend up to 12 hours transporting tourists to and from breeding sites. Such large-ship operations expose wildlife to humans far longer than smaller vessels.[14]

Moreover, the Spirit of Enderby has been conducting cruises to the Ross Sea region for many years, including McMurdo Sound. Although the Enderby has an ice-strengthened hull, the ship is not an icebreaker. The Enderby sports zodiac boats, a hovercraft for Antarctica voyages, and all-terrain vehicles (oceanadventures.co.uk) for over ice or overland travel. Land-based tourism in Antarctica, however, continues to be rare. Antarctica lacks a permanent land-based tourism facility, despite the annual surge in the number of visitors.

Prominent features

Beaufort Island

This small island at the northern entrance to McMurdo Sound is a protected area due to its site as a penguin rookery.Black Island (Ross Archipelago)

This island is located west of nearby White Island and is about 25 miles (40 km) from McMurdo Station. An unmanned telecommunications base is located here.Cape Royds

Protected area with the most southerly Adelie penguin colony (Antarctica New Zealand). The site features an expedition hut built by Ernest Shackleton and his crew of the Nimrod in 1907 on western shore of Ross Island.Discovery Point

Also referred to as Hut Point, which overlooks Winter Quarters Bay. Location of the expedition hut built by the British Antarctic Expedition(1901–04) led by Robert Falcon Scott.Glacier Ice Tongues

Erebus Ice Tongue projects 11–12 km from the coastline, reaching up to 10 meters in height. Ice flowing rapidly from the glacier at the base of Mt. Erebus forms the ice structure. MacKay Glacier Tongue is located across the sound to the northwest at Granite Harbor.McMurdo Dry Valleys

This row of valleys on the western shore are so named because of their extremely low humidity and their lack of snow or ice cover.McMurdo Ice Shelf

This floating ice shelf forms the southern boundary of McMurdo Sound and is itself part of the larger Ross Ice Shelf.Mount Discovery

This isolated volcanic cone on the western shore of McMurdo Sound reaches 2,681 meters (8,796 ft) in height.Mount Erebus

Mount Erebus is the southernmost active volcano on Earth. (Antarctic Connection). The mountain reaches 3,794 meters (12,448 ft) in height and is located on Ross Island.Ross Island

Ross Island features four principal volcanoes: Mounts Erebus, Terror, Bird, and Terra Nova. The United States and New Zealand scientific bases are located on the southern end of the island.Royal Society Range

This volcanic range is part of the Transantarctic Mountains, one of the world’s longest mountain chains (Antarctic Connection). The Royal Society Range is located on McMurdo Sound’s southwestern shore.White Island (Ross Archipelago)

The McMurdo Ice Shelf encircles White Island, which is visible from Scott Base. A perennial tidal crack in the ice permits weddell seals to live at the island year round. (Texas A&M University at Galveston LABB)Gallery

See also

- Erebus Ice Tongue

- Marble Point

- McMurdo Station

- Ross Sea

- Scott Base

- Williams Field

- Winter Quarters Bay

Notes

- ^ Christine Elliott (May 2005). "Antarctica, Scott Base and its environs". New Zealand Geographer 61 (1): 68–76. doi:10.1111/j.1745-7939.2005.00005.x. http://www.blackwell-synergy.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1745-7939.2005.00005.x. Retrieved 2007-05-23.

- ^ "NSF 92-134 Facts about the US Antarctic Program". National Science Foundation. 7 November 1994. http://www.nsf.gov/pubs/stis1994/nsf92134/nsf92134.txt. Retrieved 2007-05-23.

- ^ Richard Harris (October 5, 2006). "Alaskan Storm Plays Role of Butterfly for Antarctica". National Public Radio. http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=6204027. Retrieved 2007-05-23.

- ^ Jennifer Goldblatt (April 1, 2001). "Aboard the Braveheart: In search of a monster iceberg". St. Petersburg Times (Florida). http://www.sptimes.com/News/040101/Pasco/In_search_of_a_monste.shtml. Retrieved 2007-05-23.

- ^ a b "The world's frozen clean room". Business Week. January 22, 1990.

- ^ Tim Radford (November 17, 2001). "Thaw puts husky hazards in the path of Scott's successors". The Guardian. http://environment.guardian.co.uk/climatechange/story/0,,1829739,00.html. Retrieved 2007-05-23.

- ^ a b Ray Lilley (November 18, 2001). "Antarctic sea floor contaminated by human waste near bases". Archived from the original on 2007-09-26. http://web.archive.org/web/20070926235303/http://enn.com/archive.html?id=24782&cat=archives. Retrieved 2007-05-23.

- ^ MSNBC.com (December 4, 2006). "Reflections from time on the Ice". http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/15834019/page/5/. Retrieved 2007-05-23.

- ^ "U.S. Antarctic Base at McMUrdo Sound a Dump; Environment: Trashing began in last century with the start of exploration. The waste are is fenced off to slow the escape of wind-blown rubbish", Reuters. December 29, 1991.

- ^ Antarctic dump leaks waste", Courier Mail. March 20, 1991.

- ^ "Toxic chemicals from ice-breaking ships are polluting Antarctic seas", New Scientist. May 22, 2004. This article cites a study by the Australian Institute of Marine Science, which was slated to be published in the Marine Pollution Bulletin.

- ^ "NSF chooses alternative method to refuel its main Antarctic research station; Unusual, multi-year ice conditions keep tanker out of McMurdo Station", M2 Presswire. February 27, 2003

- ^ "Antarctic Research: Station recharged by ship via miles of fule lines, Science Letter via NewsRx.com and NewsRx.net. March 17, 2003

- ^ a b "Is rise in tourism helping Antarctica or hurting it?", Travel Watch; National Geographic Traveler. August 22, 2003.

- ^ "IAATO Tourism Statistics". http://www.iaato.org/tourism_stats.html.

References

- A Special Place, Australian Government Antarctic Division.

- Antarctic Connection.

- Antarctica New Zealand Information Sheet.

- Antarctic Climate & Ecosystems: Cooperative Research Center

- The Aster Project.

- British Antarctic Survey.

- Clarke, Peter; On the Ice, Rand McNally & Company 1966.

- Evolution of antifreeze glycoprotein gene from a trypsinogen gene in Antarctic notothenioid fish, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States December 2006.

- Field Manual for the U.S. Antarctic Program.

- First Ever Voyages, Quark Expeditions.

- Fresh Fish, Not Frozen, Origins: Antarctica. Scientific Journeys from McMurdo to the Pole.

- Frozen continent: Time to clean up the ice, New Zealand Herald. January 6, 2004.

- Historical Development of McMurdo Station, Antarctica, an Environmental Perspective, Department of Geography, Texas A&M University; Geochemical and Environmental Research Group, Texas A&M; Uniondale High School, Uniondale New York.

- Ice Bomb Goes Off. National Geographic.

- Icebreakers Clear Channel into McMurdo Station. February 3, 2005.

- International Association of Antarctica Tour Operations (IAAT0).

- Laboratory for Applied Biotelemetry & Biotechnology.

- Management Plan for Antarctic Specially Protected Area (ASPA) No. 121. Antarctica New Zealand.

- MCMURDO DRY VALLEYS REGION, TRANSANTARCTIC MOUNTAINS, National Science Foundation

- McMurdo Station Weather (USA Today).

- NASA's Earth Observatory.

- NewsRx.com

- National Public Radio

- Paint polluting Antarctic, Herald Sun; Melbourne, Australia. May 21, 2004.

- Runaway Iceberg, Reed Business Information, UK; April 16, 2005.

- U.S., Russian icebreakers open path to Antarctic base. USA Today; February 6, 2005.

- The Guardian

- U.S. Antarctic Base at McMurdo Sound a Dump, Reuters News Agency. December 29, 1991.

- Understanding polar weather, USA Today. May 20, 2005.

- Underwater Field Guide to Ross Island & McMurdo Sound.

- U.S. Antarctic Program.

- Where the Wind Blows, Anatarctic Sun. January 28, 2001.

- Why is Antarctica so cold?, Antarctic Connection.

External links

- Antarctica New Zealand.

- Antarctic Photo Library.

- Antarctic Sun.

- Australian Government Antarctic Division.

- British Antarctic Survey.

- International Association of Antarctic Tour Operators.

- International Ice Patrol Student Section.

- National Science Foundation.

- New Zealand Antarctic Heritage Trust.

Antarctica Main articles - Antarctic

- History

- Geography

- Climate

- Expeditions

- Research stations

- Field camps

- Territorial claims

- Antarctic Treaty System

- Telecommunications

- Demographics

- Economy

- Tourism

- Transport

- Military activity in the Antarctic

Geographic regions - Antarctic Peninsula

- East Antarctica

- West Antarctica

- Extreme points of the Antarctic

- List of Antarctic and subantarctic islands

- Antarctica ecozone

Waterways - Southern Ocean

- McMurdo Sound

- Ross Sea

- Weddell Sea

Famous explorers  Portal:AntarcticaCategories:

Portal:AntarcticaCategories:- Sounds of Antarctica

- Landforms of the Ross Dependency

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.