- Nasreddin

-

For other uses, see Nasreddin (disambiguation).

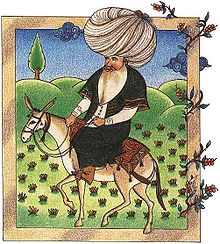

A 17th century miniature of Nasreddin, currently in the Topkapi Palace Museum Library.

A 17th century miniature of Nasreddin, currently in the Topkapi Palace Museum Library.

Nasreddin (Persian: خواجه نصرالدین Arabic: نصرالدین جحا / ALA-LC: Naṣraddīn Juḥā, Ottoman Turkish: نصر الدين خواجه, Nasreddīn Hodja) was a Seljuq satirical Sufi figure, sometimes believed to have lived during the Middle Ages (around 13th century) and considered a populist philosopher and wise man, remembered for his funny stories and anecdotes.[1] He appears in thousands of stories, sometimes witty, sometimes wise, but often, too, a fool or the butt of a joke. A Nasreddin story usually has a subtle humour, but it is claimed that within the tale there is usually also something to be learned.[2] The International Nasreddin Hodja fest is celebrated between 5–10 July in Aksehir, Turkey every year.[3]

Contents

Origin and legacy

Hodja-park in Akşehir

Hodja-park in Akşehir

Although he is very likely Turkic in ancestry, claims about his origin are made by many ethnic groups.[4][5] Many sources give the birthplace of Nasreddin as Hortu Village in Sivrihisar, Eskişehir Province, present-day Turkey, in the 13th century, after which he settled in Akşehir[5], and later in Konya under the Seljuq rule, where he died in 1275/6 or 1285/6 CE.[6][7] The alleged tomb of Nasreddin is in Akşehir[8] and the "International Nasreddin Hodja Festival" is held annually in Akşehir between 5–10 July.[9]

As generations have gone by, new stories have been added to the Nasreddin corpus, others have been modified, and he and his tales have spread to many regions. The themes in the tales have become part of the folklore of a number of nations and express the national imaginations of a variety of cultures. Although most of them depict Nasreddin in an early small-village setting, the tales, like Aesop's fables, deal with concepts that have a certain timelessness. They purvey a pithy folk wisdom that triumphs over all trials and tribulations. The oldest manuscript of Nasreddin dates to 1571.

Today, Nasreddin stories are told in a wide variety of regions, especially across the Muslim world and have been translated into many languages. Some regions independently developed a character similar to Nasreddin, and the stories have become part of a larger whole. In many regions, Nasreddin is a major part of the culture, and is quoted or alluded to frequently in daily life. Since there are thousands of different Nasreddin stories, one can be found to fit almost any occasion.[10] Nasreddin often appears as a whimsical character of a large Albanian, Arabic, Armenian, Azerbaijani, Bengali, Bosnian, Bulgarian, Chinese, Greek, Gujarati, Hindi, Italian, Judeo-Spanish, Kurdish, Pashto, Persian, Romanian, Serbian, Russian, Turkish and Urdu folk tradition of vignettes, not entirely different from zen koans.

1996–1997 was declared International Nasreddin Year by UNESCO.[11]

Some people say that, whilst uttering what seemed madness, he was, in reality, divinely inspired, and that it was not madness but wisdom that he uttered.

—The Turkish Jester or The Pleasantries of Cogia Nasr Eddin Effendi[12]

Name

Many peoples of the Near, Middle East and Central Asia claim Nasreddin as their own (e.g., Turks,[1][6][13][14] Afghans,[13] Iranians,[1][15] and Uzbeks).[7] His name is spelt in a wide variety of ways: Nasrudeen, Nasrudin, Nasruddin, Nasr ud-Din, Nasredin, Naseeruddin, Nasr Eddin, Nastradhin, Nasreddine, Nastratin, Nusrettin, Nasrettin, Nostradin and Nastradin (lit.: Victory of the Deen). It is sometime preceded or followed by a title or honorific used in the corresponding cultures: "Hoxha", "Khwaje", "Hodja", "Hojja","Hodscha", "Hodža", "Hoca", "Hogea", "Mullah", "Mulla", "Mula", "Molla", "Efendi", "Afandi", "Ependi" (أفندي ’afandī), "Hajji". In several cultures he is named by the title alone.

In Arabic-speaking countries this character is known as "Juha", "Djoha", "Djuha", "Dschuha", "Giufà", "Chotzas", "Goha" (جحا juḥā). Juha was originally a separate folk character found in Arabic literature as early as the 9th century, and was widely popular by the 11th century.[16] Lore of the two characters became amalgamated in the 19th century when collections were translated from Arabic into Turkish and Persian.[17]

In the Swahili culture many of his stories are being told under the name of "Abunuwasi", though this confuses Nasreddin with an entirely different man – the poet Abu Nuwas, known for homoerotic verse.

In China, where stories of him are well known, he is known by the various transliterations from his Uyghur name, 阿凡提 (Āfántí) and 阿方提 (Āfāngtí). The Uyghurs do not believe that Āfántí lived in Anatolia; according to the them, he was from Eastern Turkistan.[18] Shanghai Animation Film Studio produced a 13-episode Nasreddin related animation called 'The Story of Afanti'/ 阿凡提 (电影) in 1979, which became one of the most influential animations in China's history.

In Central Asia, he is commonly known as "Afandi".

Tales

The Nasreddin stories are known throughout the Middle East and have touched cultures around the world. Superficially, most of the Nasreddin stories may be told as jokes or humorous anecdotes. They are told and retold endlessly in the teahouses and caravanserais of Asia and can be heard in homes and on the radio. But it is inherent in a Nasreddin story that it may be understood at many levels. There is the joke, followed by a moral and usually the little extra which brings the consciousness of the potential mystic a little further on the way to realization.[19]

Examples

Delivering a sermon

- Once Nasreddin was invited to deliver a sermon. When he got on the pulpit, he asked, Do you know what I am going to say? The audience replied "no", so he announced, I have no desire to speak to people who don't even know what I will be talking about! and left.

- The people felt embarrassed and called him back again the next day. This time, when he asked the same question, the people replied yes. So Nasreddin said, Well, since you already know what I am going to say, I won't waste any more of your time! and left.

- Now the people were really perplexed. They decided to try one more time and once again invited the Mulla to speak the following week. Once again he asked the same question – Do you know what I am going to say? Now the people were prepared and so half of them answered "yes" while the other half replied "no". So Nasreddin said Let the half who know what I am going to say, tell it to the half who don't, and left.[20]

Whom do you trust

Nasreddin Hodja in Alanya

Nasreddin Hodja in Alanya

Nasreddin Hodja in Ankara

Nasreddin Hodja in Ankara

- A neighbour came to the gate of Mulla Nasreddin's yard. The Mulla went to meet him outside.

- "Would you mind, Mulla," the neighbour asked, "lending me your donkey today? I have some goods to transport to the next town."

- The Mulla didn't feel inclined to lend out the animal to that particular man, however. So, not to seem rude, he answered:

- "I'm sorry, but I've already lent him to somebody else."

- All of a sudden the donkey could be heard braying loudly behind the wall of the yard.

- "But Mulla," the neighbour exclaimed. "I can hear it behind that wall!"

- "Who do you believe," the Mulla replied indignantly. "The donkey or your Mulla?"[21]

Taste the same

- Some children saw Nasreddin coming from the vineyard with two basketfuls of grapes loaded on his donkey. They gathered around him and asked him to give them a taste.

- Nasreddin picked up a bunch of grapes and gave each child a grape.

- "You have so much, but you gave us so little," the children whined.

- "There is no difference whether you have a basketful or a small piece. They all taste the same," Nasreddin answered, and continued on his way.[22]

Habit

- One day when Nasreddin was having his regular daily coffee at his usual seat in his usual outdoor café, a schoolboy came along and knocked off his turban. Unperturbed, Nasreddin picked up the turban and put it back on his head. The next day, the same schoolboy came along and knocked off his turban again. Again, Nasreddin just picked it up, put it back on and resumed whatever conversation he was having. When the little brat repeated the prank for the third time, his friends protested and told him to scold the boy.

- "Tsk, tsk. That's not how this principle is working," said Nasreddin offhandedly.

- The next day, an invading army occupied the city and Nasreddin did not turn up for coffee as usual. In his seat was a captain from the invading army. When the schoolboy passed by as usual, he knocked off the soldier's hat without a second thought and the captain sliced off his head with a swift single stroke of his sword.[cite this quote]

Reaching enlightenment

- Nasreddin was walking in the bazaar with a large group of followers. Whatever Nasreddin did, his followers immediately copied. Every few steps Nasreddin would stop and shake his hands in the air, touch his feet and jump up yelling "Hu Hu Hu!". So his followers would also stop and do exactly the same thing.

- One of the merchants, who knew Nasreddin, quietly asked him: "What are you doing my old friend? Why are these people imitating you?"

- "I have become a Sufi Sheikh," replied Nasreddin. "These are my Murids (spiritual seekers); I am helping them reach enlightenment!"

- "How do you know when they reach enlightenment?"

- "That’s the easy part! Every morning I count them. The ones who have left – have reached enlightenment!"

- [cite this quote]

Azerbaijani literature

Main article: Molla Nasraddin (magazine)Nasreddin was the main character in a magazine, called simply Molla Nasraddin, published in Azerbaijan and "read across the Muslim world from Morocco to Iran". The eight-page Azerbaijani satirical periodical was published in Tiflis (from 1906 to 1917), Tabriz (in 1921) and Baku (from 1922 to 1931) in the Azeri and occasionally Russian languages. Founded by Jalil Mammadguluzadeh, it depicted inequality, cultural assimilation, and corruption and ridiculed the backward lifestyles and values of clergy and religious fanatics.[23], implicitly calling upon the readers to modernize and accept Western social norms and practices. The magazine was frequently banned[24] but had a lasting influence on Azerbaijani and Iranian literature.[25]

European and Western folk tales, literary works and pop culture

Some Nasreddin tales also appear in collections of Aesop's fables. The miller, his son and the donkey is one example.[26] Others are The Ass with a Burden of Salt (Perry Index 180) and The Satyr and the Traveller.

In some Bulgarian folk tales that originated during the Ottoman period, the name appears as an antagonist to a local wise man, named Sly Peter. In Sicily the same tales involve a man named Giufà.[27] In Sephardi Jewish culture, spread throughout the Ottoman Empire, there is a character that appears in many folk tales named Djohá.[28][29]

While Nasreddin is mostly known as a character from short tales, whole novels and stories have later been written and an animated feature film was almost made.[30] In Russia Nasreddin is known mostly because of the novel "Tale of Hodja Nasreddin" written by Leonid Solovyov (English translations: "The Beggar in the Harem: Impudent Adventures in Old Bukhara," 1956, and "The Tale of Hodja Nasreddin: Disturber of the Peace," 2009[31]). The composer Shostakovich celebrated Nasreddin, among other figures, in the second movement (Yumor, 'Humor') of his Symphony No. 13. The text, by Yevgeny Yevtushenko, portrays humor as a weapon against dictatorship and tyranny. Shostakovich's music shares many of the 'foolish yet profound' qualities of Nasreddin's sayings listed above.[citation needed]

Tinkle, an Indian comic book for children, has Nasruddin Hodja as a recurring character

Uzbek Nasreddin Afandi

The ever-smiling Hodja riding on his bronze donkey in Bukhara.

The ever-smiling Hodja riding on his bronze donkey in Bukhara.

For Uzbek people, Nasreddin is one of their own, and was born and lived in Bukhara.[18] In gatherings, family meetings, and parties they tell each other stories about him that are called "latifa" of "afandi".

There are at least two collections of stories related to Nasriddin Afandi.

Books on him:

- "Afandining qirq bir passhasi" – (Forty-one flies of Afandi) – Zohir A'lam, Tashkent

- "Afandining besh xotini" – (Five wives of Afandi)

In 1943, the Soviet film Nasreddin in Bukhara was directed by Yakov Protazanov based on Solovyov's book, followed in 1947 by a film called The Adventures of Nasreddin, directed by Nabi Ganiyev and also set in the Uzbekistan SSR.[32][33]

Collections

- 600 Mulla Nasreddin Tales, collected by Mohammad Ramazani (Popular Persian Text Series: 1) (in Persian).

- The Exploits of the Incomparable Mulla Nasreddin, by Idries Shah, illustrated by Richard Williams

- The Subtleties of the Inimitable Mulla Nasreddin, by Idries Shah, illustrated by Richard Williams.

- The Pleasantries of the Incredible Mulla Nasreddin, by Idries Shah, illustrated by Richard Williams and Errol Le Cain

- Mullah Nasiruddiner Galpo (Tales of Mullah Nasreddin) collected and retold by Satyajit Ray, (in Bengali)

- The Wisdom of Mulla Nasruddin, by Shahrukh Husain

- The Uncommon Sense of the Immortal Mullah Nasruddin: Stories, jests, and donkey tales of the beloved Persian folk hero, collected and retold by Ron Suresha

- Kuang Jinbi (2004). The magic ox and other tales of the Effendi.. ISBN 978-1410106926.

References

- ^ a b c The outrageous Wisdom of Nasruddin, Mullah Nasruddin; accessed 19 February 2007.

- ^ Javadi, Hasan. "MOLLA NASREDDIN i. THE PERSON". Encyclopaedia Iranica. http://iranica.com/articles/molla-nasreddin-i-the-person. Retrieved 5 July 2011.

- ^ http://www.aksehir.bel.tr/portal/index.php/nasreddin-hoca/nasreddin-hoca-senligi

- ^ İlhan Başgöz, Studies in Turkish folklore, in honor of Pertev N. Boratav, Indiana University, 1978, p. 215. ("Quelle est la nationalité de Nasreddin Hodja – est-il turc, avar, tatar, tadjik, persan ou ousbek? Plusieurs peuples d'Orient se disputent sa nationalité, parce qu'ils considerent qu'il leur appartient.") (French)

- ^ a b John R. Perry, "Cultural currents in the Turco-Persian world", in New Perspectives on Safavid Iran: Majmu`ah-i Safaviyyah in Honour of Roger Savory, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 9781136991943, p. 92.

- ^ a b "Nasreddin Hoca". Republic of Turkey Ministry of Culture and Tourism. http://www.kultur.gov.tr/EN/BelgeGoster.aspx?17A16AE30572D3138DF7C92FCA5B4D0584F186FD0FCCD518. Retrieved 28 December 2006.

- ^ a b Fiorentini, Gianpaolo (2004). "Nasreddin, una biografia possibile". Storie di Nasreddin. Torino: Libreria Editrice Psiche. ISBN 8885142710. http://www.psiche.info/estratti/psiche/StorieDiNasreddin.htm. Retrieved 28 December 2006.

- ^ Set of photos of the tomb by Faruk Tuncer on flickr.com, including a plaque marking the Centre of the Earth

- ^ Aksehir's International Nasreddin Hodja Festival and Aviation Festival – Turkish Daily News 27 Jun 2005

- ^ Ohebsion, Rodney (2004) A Collection of Wisdom, Immediex Publishing, ISBN 1-932968-19-9.

- ^ "...UNESCO declared 1996–1997 the International Nasreddin Year...".

- ^ The Turkish Jester or The Pleasantries of Cogia Nasr Eddin Effendi. Translated by George Borrow. 1884. http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/16244.

- ^ a b Sysindia.com, Mulla Nasreddin Stories, accessed 20 February 2007.

- ^ Silk-road.com, Nasreddin Hoca

- ^ "First Iranian Mullah who Was a Master in Anecdotes". Persian Journal. http://www.iranian.ws/iran_news/publish/printer_28786.shtml. Retrieved 26 July 2009.

- ^ Josef W. Meri, ed (2006). Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia. 1: A–K. p. 426. ISBN 0415966914. http://books.google.com/books?id=MypbfKdMePIC&pg=PA426.

- ^ Donald Haase, ed (2008). The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Folktales and Fairy Tales. 2: G–P. p. 661. ISBN 9780313334436. http://books.google.com/books?id=-sj5cJz0_OsC&pg=PA661.

- ^ a b Harid Fedai, Mulla or Hodja Nasreddin as seen by Cypriot Turks and Greeks

- ^ Idris Shah (1964), The Sufis, London: W. H. Allen ISBN 0-385-07966-4.

- ^ Many written versions of this tale exist, for example in Kelsey, Alice (1943). Once the Hodja. David McKay Company Inc.

- ^ Widely retold, for instance in Shah, Idries (1964). The Sufis. Jonathan Cape. pp. 78–79. ISBN SBN 0-863040-74-8.

- ^ A similar story is presented in Shah, Idries (1985). The subtleties of the inimitable Mulla Nasrudin (Reprinted. ed.). London: Octagon Press. p. 60. ISBN 0863040403.

- ^ Molla Nasraddin – The Magazine: Laughter that Pricked the Conscience of a Nation by Jala Garibova. Azerbaijan International. #4.3. Autumn 1996

- ^ (Russian) Molla Nasraddin, an entry from the Great Soviet Encyclopaedia by A.Sharif. Baku.ru

- ^ (Persian) Molla Nasraddin and Jalil Mammadguluzadeh by Ebrahim Nabavi. BBC Persian. 6 July 2006

- ^ The Man, the Boy, and the Donkey, Folktales of Aarne-Thompson-Uther Type 1215 translated and/or edited by D. L. Ashliman

- ^ Google Books Search

- ^ Tripod.com, Djoha – Personaje – Ponte en la Area del Mediterraneo

- ^ Sefarad.org, European Sephardic Institute

- ^ Dobbs, Mike (1996), "An Arabian Knight-mare", Animato! (35)

- ^ Solovyov, Leonid (2009). The Tale of Hodja Nasreddin: Disturber of the Peace. Toronto, Canada: Translit Publishing. ISBN 9780981269504. http://translit.ca/books.html#disturber.

- ^ Cinema of Uzbekistan list on mubi.com

- ^ «Большой Словарь: Крылатые фразы отечественного кино», Олма Медиа Групп,. 2001г., ISBN 9785765417355, p. 401.

External links

- Works by Nasreddin Hoca at Project Gutenberg

- ELEMENTS OF HUMOR IN CENTRAL ASIA: THE EXAMPLE OF THE JOURNAL MOLLA NASREDDIN IN AZARBAIJAN

- Benjamin Franklin and Nasreddin of Asia Minor

- Introduction to Keloglan, on Nasreddin

- Several illustrated Hodja stories

- Gold donkey of Nasreddin Hodja. Play (in Russian)

Azerbaijani Turkic Literature Medieval Izzaddin Hasanoglu · Nasir Bakui · Kadi Burhan al-Din · Darir of Arzurum · Jahan Shah Haqiqi · Habibi · Qasim Al-Anvar · Imadaddin Nasimi · Y‘aqub ibn Uzun Hasan · Shah Ismayil Khatai · Hagiri Tabrizi · Kishveri · Muhammad Fuzuli · Shah Abbas Sani · Mahammad Amani · Saib Tabrizi · Qusi Tabrizli · Roohi Bagdadi · Mesihi · Tarzi Afshar · Fatma Khanum AniModern Molla Panah Vagif · Molla Vali Vidadi · Mirza Shafi Vazeh · Khurshidbanu Natavan · Abbasgulu Bakikhanov · Mirza Fatali Akhundov · Gasim bey Zakir · Seyid Azim Shirvani · Hasan bey Zardabi · Mirza Alakbar Sabir · Seyid Abulgasim Nabati · Heyran Khanum · Jalil Mammadguluzadeh · Nariman Narimanov · Abdurrahim bey Hagverdiyev · Ismayil bey Gutgashynly · Sakina Akhundzadeh · Suleyman Sani Akhundov · Yusif Vazir Chamanzaminli · Mammed Said Ordubadi · Najaf bey Vazirov · Ashig Alasgar · Muhammad Hadi · Abbas Sahhat · Abdulla Shaig · Huseyn Javid · Jafar Jabbarly · Mikayil Mushfig · Samad Vurgun · Aliagha Vahid · Ahmad Jamil · Mirza KhazarContemporary Suleyman Rustam · Rasul Rza · Nigar Rafibeyli · Mirza Ibrahimov · Almas Ildyrym · Mirvarid Dilbazi · Ismayil Shykhly · Manaf Suleymanov · Baba Punhan · Anar Rzayev · Fikrat Goja · Nusrat Kasamanli · Elchin Efendiyev · Khalil Rza Uluturk · Bakhtiyar Vahabzadeh · Mammad Araz · Magsud Ibrahimbeyov · Rustam Ibrahimbeyov · Chingiz Abdullayev · Natig Rasulzadeh · Afag Masud · Akram Aylisli · Samad Behrangi · Mohammad-Hossein Shahriar · Madina Gulgun · Samin Baghtcheban · Jabbar Baghtcheban · Sahand · Saher · Ali Mojuz · Vidadi Babanli · Hidayet · Lala Hasanova · Narmin Kamal · Gasham NajafzadehNotes Turkish Literature Folk Aşık Mahzuni Şerif · Âşık Veysel Şatıroğlu · Dadaloğlu · Erzurumlu Emrah · Gevheri · Hacı Bektaş-ı Veli · Karacaoğlan · Kaygusuz Abdal · Nasreddin · Neşet Ertaş · Pir Sultan Abdal · Seyrani · Yunus EmreMedieval and

OttomanImadaddin Nasimi · Fuzûlî · Bâkî · Nef‘î · Nedîm · Şeyh Gâlib · Evliya Çelebi · Kâtib Çelebi · Yirmisekiz Mehmed Çelebi · Aşık Çelebi · Ziya Pasha · Şemsettin Sami · Namık Kemal · Ahmed Midhat Efendi · Tevfik Fikret · Cenâb Şehâbeddîn · Halit Ziya Uşaklıgil · Ahmet Haşim · Ömer Seyfettin · Mehmet Emin Yurdakul · Ali Canip Yöntem · Mirza Habib Esfahani · Fatma Aliye TopuzContemporary Halide Edip Adıvar · Reşat Nuri Güntekin · Yakup Kadri Karaosmanoğlu · Mehmet Fuat Köprülü · Cevat Şakir Kabaağaçlı · Ahmet Hamdi Tanpınar · Orhan Kemal · Murathan Mungan · Orhan Hançerlioğlu · Samim Kocagöz · Semiha Ayverdi · Tarık Buğra · Yusuf Atılgan · Yaşar Kemal · Fakir Baykurt · Bilge Karasu · Oğuz Atay · Tomris Uyar · Ahmet Altan · Orhan Pamuk · Elif Şafak · Memduh Şevket Esendal · Kenan Hulusi Koray · Sait Faik Abasıyanık · Kemal Tahir · Haldun Taner · Aziz Nesin · Suut Kemal Yetkin · Sabahattin Ali · Kemal Bilbaşar · Cemil Meriç · Ruşen Eşref Ünaydın · Nurullah Ataç · Behçet Necatigil · Necati Cumalı · Ayfer Tunç · Yekta Kopan · Ahmet Kutsi Tecer · Şevket Süreyya Aydemir · Mehmet Emin Yurdakul · Ziya Gökalp · Orhan Veli Kanık · Oktay Rıfat Horozcu · Melih Cevdet Anday · Nazım Hikmet · Rıfat Ilgaz · Cemal Süreya · İlhan Berk · Turgut Uyar · Edip Cansever · Ece Ayhan Çağlar · Sezai Karakoç · Tevfik Akdağ · Ülkü Tamer · Neyzen Tevfik · Ahmet Haşim · Yahya Kemal Beyatlı · Abdülhak Şinasi Hisar · Orhan Seyfi Orhon · Enis Behiç Koryürek · Halit Fahri Ozansoy · Yusuf Ziya Ortaç · Muammer Lütfi Bakşi · Necip Fazıl Kısakürek · Vasfi Mahir Kocayürek · Sabri Esat Siyavuşgil · Cevdet Kudret · Yaşar Nabi Nayır · Ahmet Muhip Dıranas · Cahit Sıtkı Tarancı · Ziya Osman Saba · Faik Baysal · Salah Birsel · Özdemir Asaf · N. Abbas Sayar · Can Yücel · Attilâ İlhan · Güven Turan · İsmet Özel · Cem Uzungüneş · Mehmet Altun · Mehmet Erte · Küçük İskender · Faruk Nafiz Çamlıbel · Fazıl Hüsnü Dağlarca · Yusuf Atılgan · Murat Gülsoy · Ayşe Kulin · Yılmaz OnayPersian literature Old Middle Ayadgar-i Zariran · Counsels of Adurbad-e Mahrspandan · Dēnkard · Book of Jamasp · Book of Arda Viraf · Karnamak-i Artaxshir-i Papakan · Cube of Zoroaster · Dana-i_Menog_Khrat · Shabuhragan of Mani · Shahrestanha-ye Eranshahr · Bundahishn · Greater Bundahishn · Menog-i Khrad · Jamasp Namag · Pazand · Dadestan-i Denig · Zadspram · Sudgar Nask · Warshtmansr · Zand-i Vohuman Yasht · Drakht-i Asurig · Bahman Yasht · Shikand-gumanic VicharClassical 900s–1000sRudaki · Abu-Mansur Daqiqi · Ferdowsi (Shahnameh) · Abu Shakur Balkhi · Bal'ami · Rabia Balkhi · Abusaeid Abolkheir (967–1049) · Avicenna (980–1037) · Unsuri · Asjadi · Kisai Marvazi · Ayyuqi1000s–1100sBābā Tāher · Nasir Khusraw (1004–1088) · Al-Ghazali (1058–1111) · Khwaja Abdullah Ansari (1006–1088) · Asadi Tusi · Qatran Tabrizi (1009–1072) · Nizam al-Mulk (1018–1092) · Masud Sa'd Salman (1046–1121) · Moezi Neyshapuri · Omar Khayyām (1048–1131) · Fakhruddin As'ad Gurgani · Ahmad Ghazali · Hujwiri · Manuchehri · Ayn-al-Quzat Hamadani (1098–1131) · Uthman Mukhtari · Abu-al-Faraj Runi · Sanai · Banu Goshasp · Borzu-Nama · Afdal al-Din Kashani · Abu'l Hasan Mihyar al-Daylami · Mu'izzi · Mahsati Ganjavi1100s–1200sHakim Iranshah · Suzani Samarqandi · Ashraf Ghaznavi · Faramarz Nama · Shahab al-Din Suhrawardi (1155–1191) · Adib Sabir · Am'aq · Najm-al-Din Razi · Attār (1142–c.1220) · Khaghani (1120–1190) · Anvari (1126–1189) · Faramarz-e Khodadad · Nizami Ganjavi (1141–1209) · Fakhr al-Din al-Razi (1149–1209) · Kamal al-din Esfahani · Shams Tabrizi (d.1248)1200s–1300sAbu Tahir Tarsusi · Najm al-din Razi · Awhadi Maraghai · Shams al-Din Qays Razi · Baha al-din Walad · Nasīr al-Dīn al-Tūsī · Baba Afdal al-Din Kashani · Fakhr al-din Araqi · Mahmud Shabistari (1288–1320s) · Abu'l Majd Tabrizi · Amir Khusro (1253–1325) · Saadi (Bustan / Golestān) · Bahram-e-Pazhdo · Zartosht Bahram e Pazhdo · Rumi · Homam Tabrizi (1238–1314) · Nozhat al-Majales · Khwaju Kermani · Sultan Walad1300s–1400sIbn Yamin · Shah Ni'matullah Wali · Hafez · Abu Ali Qalandar · Fazlallah Astarabadi · Nasimi · Emad al-Din Faqih Kermani1400s–1500s1500s–1600sVahshi Bafqi (1523–1583) · 'Orfi Shirazi1600s–1700sSaib Tabrizi (1607–1670) · Kalim Kashani · Hazin Lāhiji (1692–1766) · Saba Kashani · Bidel Dehlavi (1642–1720)1700s–1800sNeshat Esfahani · Forughi Bistami (1798–1857) · Mahmud Saba Kashani (1813–1893)Contemporary PoetIran· Ali Abdolrezaei · Ahmadreza Ahmadi · Mehdi Akhavan-Sales · Hormoz Alipour · Qeysar Aminpour · Mohammadreza Aslani · Aref Qazvini · Manouchehr Atashi · Mahmoud Mosharraf Azad Tehrani · Mohammad-Taqi Bahar · Reza Baraheni · Simin Behbahani · Hushang Ebtehaj · Bijan Elahi · Parviz Eslampour · Parvin E'tesami · Forough Farrokhzad · Hossein Monzavi · Hushang Irani · Iraj Mirza · Bijan Jalali · Siavash Kasraie · Esmail Khoi · Shams Langeroodi · Mohammad Mokhtari · Nosrat Rahmani · Yadollah Royaee · Tahereh Saffarzadeh · Sohrab Sepehri · Mohammad-Reza Shafiei Kadkani · Mohammad-Hossein Shahriar · Ahmad Shamlou · Manouchehr Sheybani · Nima YooshijAfghanistanNadia Anjuman · Wasef Bakhtari · Raziq Faani · Khalilullah Khalili · Youssof Kohzad · Massoud Nawabi · Abdul Ali Mustaghni

TajikistanSadriddin Ayni · Farzona · Iskandar Khatloni · Abolqasem Lahouti · Gulrukhsor Safieva · Loiq Sher-Ali · Payrav Sulaymoni · Mirzo TursunzodaUzbekistanPakistanIndiaNovelAli Mohammad Afghani · Ghazaleh Alizadeh · Bozorg Alavi · Reza Amirkhani · Mahshid Amirshahi · Reza Baraheni · Simin Daneshvar · Mahmoud Dowlatabadi · Reza Ghassemi · Houshang Golshiri · Aboutorab Khosravi · Ahmad Mahmoud · Shahriyar Mandanipour · Abbas Maroufi · Iraj PezeshkzadShort StoryJalal Al-e-Ahmad · Yousef Alikhani · Kourosh Asadi · Shamim Bahar · Sadeq Chubak · Simin Daneshvar · Nader Ebrahimi · Ali-Moraf Fadaeenia · Ebrahim Golestan · Houshang Golshiri · Sadegh Hedayat · Bahram Heydari · Mohammad-Ali Jamalzadeh · Aboutorab Khosravi · Mostafa Mastoor · Jaafar Modarres-Sadeghi · Houshang Moradi Kermani · Bijan Najdi · Shahrnush Parsipur · Gholam-Hossein Sa'edi · Bahram Sadeghi · Goli TaraqqiPlayReza Abdoh · Mirza Fatali Akhundzadeh · Hamid Amjad · Bahram Bayzai · Mohammad Charmshir · Alireza Koushk Jalali · Hadi Marzban · Bijan Mofid · Hengameh Mofid · Abbas Na'lbandian · Akbar Radi · Pari Saberi · Mohammad YaghoubiScreenplaySaeed Aghighi · Mohammadreza Aslani · Rakhshan Bani-E'temad · Bahram Bayzai · Hajir Darioush · Pouran Derakhshandeh · Asghar Farhadi · Bahman Farmanara · Hamid Farrokhnezhad · Farrokh Ghaffari · Behrouz Gharibpour · Bahman Ghobadi · Fereydun Gole · Ebrahim Golestan · Ali Hatami · Hossein Jafarian · Abolfazl Jalili · Ebrahim Hatamikia · Abdolreza Kahani · Varuzh Karim-Masihi · Samuel Khachikian · Abbas Kiarostami · David Mahmoudieh · Majid Majidi · Mohsen Makhmalbaf · Dariush Mehrjui · Reza Mirkarimi · Hengameh Mofid · Rasoul Mollagholipour · Amir Naderi · Jafar Panahi · Kambuzia Partovi · Rasul Sadr Ameli · Mohammad Sadri · Parviz Shahbazi · Sohrab Shahid-SalessOthersDehkhoda ·Contemporary Persian and Classical Persian are the same language, but writers since 1900 are classified as contemporary. At one time, Persian was a common cultural language of much of the non-Arabic Islamic world. Today it is the official language of Iran, Tajikistan and one of the two official languages of Afghanistan.Literature of Pakistan By language Related topics Writers · Poetry (Poets) · Books and publishing · Pak Tea House · Academy of Letters · Philosophy · Media (Journalists · Federal Union)Culture of Asia Sovereign

states- Afghanistan

- Armenia

- Azerbaijan

- Bahrain

- Bangladesh

- Bhutan

- Brunei

- Burma (Myanmar)

- Cambodia

- People's Republic of China

- Cyprus

- East Timor (Timor-Leste)

- Egypt

- Georgia

- India

- Indonesia

- Iran

- Iraq

- Israel

- Japan

- Jordan

- Kazakhstan

- North Korea

- South Korea

- Kuwait

- Kyrgyzstan

- Laos

- Lebanon

- Malaysia

- Maldives

- Mongolia

- Nepal

- Oman

- Pakistan

- Philippines

- Qatar

- Russia

- Saudi Arabia

- Singapore

- Sri Lanka

- Syria

- Tajikistan

- Thailand

- Turkey

- Turkmenistan

- United Arab Emirates

- Uzbekistan

- Vietnam

- Yemen

States with limited

recognition- Abkhazia

- Nagorno-Karabakh

- Northern Cyprus

- Palestine

- Republic of China (Taiwan)

- South Ossetia

Dependencies and

other territoriesCategories:- 1208 births

- 1284 deaths

- People from Eskişehir Province

- Iranian culture

- Persian culture

- Afghan culture

- Pakistani literature

- Humor and wit characters

- History of Islam

- Persian literature

- Rhetoric

- Folkloristic characters

- Turkish literature

- Urdu literature

- Arabic literature

- Sufi fiction

- Turkish folklore

- Iranian folklore

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.