- The Thief and the Cobbler

-

The Thief and the Cobbler

An unreleased poster made near the end of the film's production, before it was taken from Richard Williams.Directed by Richard Williams Produced by Richard Williams

Imogen SuttonScreenplay by Richard Williams

Margaret FrenchStarring See voice cast Music by Robert Folk (released versions)

Jack Maeby (additional music, Miramax version)Cinematography John Leatherbarrow Editing by Peter Bond Studio Richard Williams Productions

Allied Filmmakers (1992-1993)Distributed by The Princess and the Cobbler

Majestic Films (Australia & South Africa)

Arabian Knight

Miramax Family Films (U.S.)Release date(s) The Princess and the Cobbler

September 23, 1993 (Australia & South Africa)

Arabian Knight

August 25, 1995 (U.S.)Running time Workprint

91 minutes

The Princess and the Cobbler

77 minutes

Arabian Knight

72 minutesCountry United Kingdom Language English The Thief and the Cobbler is an animated feature film, famous for its animation and its long, troubled history. The film was conceived by Canadian animator Richard Williams, who worked 28 years on the project. Beginning production in 1964, Williams intended The Thief and the Cobbler to be his masterpiece, and a milestone in the art of animation. Due to independent funding and its complex animation, The Thief and the Cobbler was in and out of production for over two decades, until Williams, buoyed by his success as animation director on Who Framed Roger Rabbit, signed a deal in 1990 to have Warner Bros. finance and distribute the film.[1] This deal fell through when Williams was unable to complete the film on time. As Warner Bros. subsequently pulled out, The Completion Bond Company assumed control of The Thief and the Cobbler and had it finished by producer Fred Calvert without Williams.

In the process, Calvert completely re-edited the film, removing many of Williams' scenes and adding songs and voiceovers, in order to make it more marketable. Two versions were released: One was issued in Australia and South Africa in 1993 as The Princess and the Cobbler and the other in the United States in 1995 as Arabian Knight (later released under the film's original name, The Thief and the Cobbler, on home video). The Princess version was distributed by Majestic Films International and Arabian Knight by Miramax Family Films. Although neither version was a box office success, the film's history and intent has given it significant cult status among animation professionals and fans. As many animators from the Golden Age of animation were involved, the development of the film also played a significant role in preserving the knowledge and skill of animation for the newer generation of animators.[2]

Video copies of a workprint made during Richard Williams' involvement of the film often circulate within animation subcircles.[3] In addition, several different people and collectives, from animation fans to The Walt Disney Company's Roy E. Disney, have initiated restoration projects intended to create a high-quality edit of the film which would mirror Williams' original intent as closely as possible. With The Thief and the Cobbler being in production from 1964 until 1995, a total of 31 years, it surpasses the 20 year Guinness record[4] by Tiefland (1954), eventually having the longest production time for a motion picture of all time.

The film was the final appearance of Vincent Price (d. 1993), who recorded his dialogue from 1967 to 1973.

Plot

The Thief and the Cobbler (1992 workprint)

The film opens with a narrator describing a prosperous city called the Golden City, which is ruled by the sleepy King Nod and protected by three golden balls positioned atop its tallest minaret. According to a prophecy, the city would fall to a race of warlike, one-eyed monsters referred to as "one-eyes" should the balls be removed, and could only be saved by "the simplest soul with the smallest and simplest of things". Living in the city are a humble and good-hearted cobbler named Tack, and a nameless, unsuccessful yet persistent thief. Both characters are mute and have no dialogue.

The thief tries to rob Tack, leading to a scuffle that causes Tack's tacks to fall out onto the street while Zigzag, King Nod's rhyming grand vizier, walks through it. Zigzag steps on one of the tacks and orders Tack to be arrested while the thief escapes. Tack is brought before King Nod and his beautiful daughter, Princess Yum-Yum, who takes a mutual liking to Tack. Before Zigzag can convince Nod to have Tack executed, Yum-Yum saves Tack by breaking one of her shoes and ordering Tack to fix it. While repairing her shoe, Tack and Yum-Yum become increasingly attracted to each other, leaving Zigzag, who lusts after Yum-Yum and plots to take over the kingdom by marrying her, intensely jealous. Meanwhile, the thief notices the golden balls atop the minaret and decides to steal them. After breaking into the palace through a gutter, the thief steals the repaired shoe from Tack, leading the cobbler to chase him through the palace. Upon retrieving the shoe, Tack bumps into Zigzag, who notices the shoe is fixed and takes the opportunity to lock Tack in a prison cell.

From left to right: Tack the cobbler, ZigZag the grand vizier, king Nod and princess Yum-Yum. The character designs are a combination of UPA and classic Disney styles,[1][5] and the overall style and flat perspective inspired by Persian miniature paintings.[3][5][6][7]

The next morning, Nod has a vision of the Golden City's doom at the hands of the one-eyes. While Zigzag tries to convince Nod of the kingdom's security under the protection of the golden balls, the thief manages to steal the balls after several failed attempts, only to lose them to Zigzag's minions. Tack escapes from his cell using his cobbling tools during the ensuing panic. Nod notices the balls' disappearance after being warned of the one-eyes by a dying soldier, who was mortally wounded during an attack against them. Zigzag attempts to use the stolen balls to blackmail the king into letting him marry Yum-Yum. When Nod refuses, Zigzag defects to the one-eyes and gives them the balls instead.

Nod sends Yum-Yum, her nanny, and Tack on a journey to ask for help from a "mad, holy old witch" who lives in the desert. They are secretly followed by the thief, who hears of treasures on the journey but has no success stealing any. They also meet a band of dimwitted brigands in the desert whom Yum-Yum declares as her royal guard. The protagonists reach the hand-shaped where the witch lives, and learn from the witch that Tack is the one prophecized to save the Golden City. The witch also presents a riddle: "Attack, attack, attack! A tack, see? But it's what you do with what you've got!"

The protagonists return to the Golden City to find the one-eyes' massive war machine approaching. Remembering the witch's riddle, Tack shoots a single tack into the enemy's midst, sparking a Goldberg-esque chain reaction that causes the war machine to slowly collapse and destroy the entire one-eye army. Zigzag tries to escape, but falls into pit filled with alligators and is eaten by them as well as his mistreated, vengeful pet vulture Phido. The thief, avoiding many deathtraps, steals the golden balls from the collapsing machine, only to have them taken away from him by Tack, after which he finally gives up and lets him have them. With peace restored and the prophecy fulfilled, the city celebrates as Tack and Yum-Yum marry; before they kiss, Tack speaks for the first and only time in the film, saying "I love you" to Yum-Yum in a deep voice. The film ends with the thief stealing the entire reel of film before running away.

Changes made in The Princess and the Cobbler (1993, Majestic Films)

The version by Fred Calvert is considerably different from Williams' workprint. Four songs have been added - the film originally had none. Many scenes have been cut: These include the thief attempting to steal various objects along with evading capital punishment for it, and the subplot where Zigzag tries to feed Tack to Phido. Also removed are any references to the "bountiful maiden from Mombassa", whom Zigzag gives to king Nod as "a plaything" in the workprint. Tack, who was (almost) mute in the original, speaks many times in the film and narrates most scenes in past tense as an older Tack: The original had narration only in the beginning by a voice over. Some subplots have been added; In one, Yum-Yum is tired of doing nothing and wants to help her father: She volunteers to be sent to the perilous journey in order to prove herself to be more than "just a pretty face". Another subplot is that there is a social class romance between Tack and Yum-Yum that is similar to Disneys' Aladdin: The Nanny scolds Yum Yum for liking a lowly cobbler so much, and is very negative towards Tack. In the original, her behaviour is very different and much more positive. Also, there are several lines of alternate or removed dialogue.

Additionally, the following scene-specific changes have been made:

- In the scene where Yum-Yum is introduced, she tells Nanny that she is tired of living a life of "regal splendor" and sings the first added song of the film, "She is More".

- The scene where ZigZag's plans are revealed to the audience has been moved to an earlier point of the film (just after Tack is assigned to fix Yum-Yum's shoe).

- After ZigZag puts Tack in his cell, Tack and Yum-Yum sing the second song, "Am I Feeling Love?".

- The one-eyes are revealed at the very beginning during the opening narration. The scene where the One-Eyes would have been first introduced in Williams' version has been changed to a nightmare for King Nod, who then calls Zigzag immediately. The king had a nightmare in the original, too, but more abstract and later in the film.

- The reason for the King refusing to let ZigZag marry Yum-Yum is that he finds it ridiculous that his minister, who is a practitioner of the black arts, should wed a princess, who is only allowed to marry someone pure of heart.

- The brigands are a troupe of loafers who were sent twenty years ago by the King to guard his borders. Because none of them are literate, they do not know when to return and have become bandits. They sing the song, "Bom Bom Bom Beem Bom" to describe their situation. Oddly, they seem to understand the text in their "Brigand's Book" very clearly.

- The Witch first appears as a floating eye, instead of being initially inside a tiny urn.

- The Witch's riddle is: "When to the wall you find your back; a tack, a tack, a tack!"

- The way the slave women kill the Mighty One-eye is changed: In the original, they chant "throne" and sit on him (He had been using them as a living throne). In this version, they throw him off the cliff.

- During the collapse of the war machine, Tack and Zigzag have a hand-to-hand fight. The fight ends with Tack sewing Zigzag's robe, disabling him.

- When One-Eye's army has been broken, the thief emerges and (pricked by conscience) willingly hands the Golden Balls to the King. When Tack and the Princess marry, there are flashbacks of all their times together up to that point, while the song "It's So Amazing" plays. Tack mentions that the thief gave him his word that he would never steal again, with the thief then shown breaking his promise by stealing the "The End" sign and the entire film.

- Because Tack now has a voice throughout the film, the gag where he has a deep voice has been removed.

Changes made in Arabian Knight (1995, Miramax)

The Miramax version includes all changes made in The Princess and the Cobbler, and adds the following:

- Several previously mute characters were given voices, most notably the thief (as Tack explains in this version, the thief is "a man of few words, but many thoughts"). Other characters that have added voices are Phido and the alligators.

- The Golden City is called Baghdad.

- The Witch is the benevolent twin sister of the evil One-Eye.

- The scenes with the witch in her human form are removed in this version of the film, leaving only a floating eye and a ghostlike image.

- The Witch's riddle is extended to: "When to the wall you find your back; a tack, a tack, a tack! Belief in yourselves is what you lack! A tack, a tack, and never look back!"

- Most scenes featuring the One-eye's slave women have been removed, although he can still be seen sitting on them.

- The scene where the Mighty One-eye dies has been removed, and he appears to be alive when his machine is shown burning (as he can be heard saying "My machine!"). Whether or not he dies afterward is unknown, although it is implied by Tack that he did - Tack says that "One-eye and his army were defeated for all eternity."

- The ending has been entirely recut. At the end, Tack becomes Prince and the first Arabian Knight. The song "It's So Amazing" has been removed. During the wedding, the thief attempts to steal the balls again. Tack ends the story by saying: "So next time you see a shooting star, be proud of who you really are. Do in your heart what you know is right, and you too shall become an Arabian Knight." Tack also mentions that the thief eventually was put in jail for years but becomes the Captain of the Guards and the king even allows him to steal one last thing which explains why he took the end sign as well as the entire film.

- The end credits for the Miramax version featured the songs It's So Amazing, the short version of Bom, Bom, Bom, Beem, Bom, and the Arnold McCuller/Andrea Robinson version of the song Am I Feeling Love?, but the end credits for the Majestic Films version only featured the songs Bom, Bom, Bom, Beem, Bom (without most of the lyrics) and the Arnold McCuller/Andrea Robinson version of the song Am I Feeling Love?.

Changes made in The Thief and the Cobbler: The Recobbled Cut (2006)

The unofficial fan restoration mostly follows the workprint very closely. Most of the changes made by Fred Calvert and Miramax are not present, but it does include a few minor Calvert scenes or alterations, depending on either if it would be useful somehow or because it couldn't be altered to fit the workprint:

- King Nod's line to his daughter, which is absent in the workprint: "My princess... I hardly know you... so brave. Just like your dear mother was! [chuckle] Very well. You will go. Look here!"

- The Mad and Holy Old Witch appearing first as an eye.

- The fight between Tack and ZigZag.

- A shot of the citizens praising the thief for returning the three golden balls.

Voice cast

Character Original version Allied Filmmakers version Miramax version Zigzag the Grand Vizier Vincent Price Tack the Cobbler Sean Connery Steve Lively Matthew Broderick (speaking)

Steve Lively (singing)Narrator Felix Aylmer Matthew Broderick Princess Yum-Yum Hilary Pritchard Bobbi Page Jennifer Beals (speaking)

Bobbi Page (singing)The Thief Unknown (never speaks)a Ed E. Carroll Jonathan Winters King Nod Anthony Quayle Clive Revill

Anthony Quayle (speech scene)bPrincess Yum-Yum's Nanny Joan Sims Mona Marshall Toni Collette Mad Holy Old Witch Mona Marshall

Joan Sims (some scenes)cChief Roofless Windsor Davies Mighty One-Eye Paul Matthews Kevin Dorsey Phido the Vulture Donald Pleasence Eric Bogosian Dying Soldier Clinton Sundberg Goblet Kenneth Williams Tickle Gofer Stanley Baxter Slap Dwarf George Melly Hoof Eddie Byrne Hook Thick Wilson Goolie Frederick Shaw Maiden from Mombassa Miriam Margolyes Laughing Brigand Richard Williams (uncredited) Speaking Brigands Joss Ackland

Peter Clayton

Derek Hinson

Declan Mulholland

Mike Nash

Dermot Walsh

Ramsay WilliamsGeoff Golden

Tony ScannellSinging Brigands Randy Crenshaw

Kevin Dorsey

Roger Freeland

Nick Jameson

Bob Joyce

Jon Joyce

Kerry Katz

Ted King

Michael Lanning

Raymond McLeod

Rick Nelson

Scott RummellAm I Feeling Love? Pop Singers Arnold McCuller

Andrea RobinsonAdditional Voices Ed E. Carroll

Steve Lively

Mona Marshall

Bobbi Page

Donald PleasenceNotes

^a In the original version of the film, the thief is heard making short grunts/wheezes in a few scenes - though not as many as in the Majestic Films version. It is unclear who provided these sounds, but it is known that Ed E. Carroll did the additional ones for the Majestic Films version.

^b Although Sir Anthony Quayle's voice was mostly redubbed by Clive Revill in the re-edited versions of the film by Miramax and Majestic Films, Quayle's voice (uncredited) can still be heard for an entire scene when King Nod gives a speech to his subjects.

^c Joan Sims' voice for the Witch was mostly redubbed by Mona Marshall, but a few lines spoken by Sims were retained when she first fully materializes and when she receives her chest of money all the way up to the part when she's in a basket lighting a match to the fumes.

Production history

Development and early production on Nasruddin (1964-1972)

Richard Williams began development work on The Thief and the Cobbler in 1964, planning to do a film about the Mulla Nasruddin, a "wise fool" of Near Eastern folklore.[8] Williams had previously illustrated a series of books by Idries Shah,[5] which collected the philosophical yet wise tales of Nasruddin.[8] Production took place at Richard Williams Productions in Soho Square, London. An early reference to the project came in the 1968 International Film Guide, which noted that Williams was about to begin work on "the first of several films based on the stories featuring Mulla Nasruddin."[8]

Like director Orson Welles before him, Williams took on television and feature-film title projects in order to fund his pet project, and work on his film progressed slowly. In 1969, the Guide noted that animation legend Ken Harris was now working on the project, which was now entitled The Amazing Nasruddin. The illustrations from the film showed intricate Indian and Persian designs.[8]

In 1970, the project was re-titled The Majestic Fool. For the first time, a potential distributor for the independent film was mentioned: British Lion Film Corporation. The International Film Guide noted that the Williams Studio's staff had increased to forty people for the production of the feature.[8]

Dialogue tracks for the film, now being referred to as Nasruddin!, were recorded at this time. Vincent Price was hired to perform the voice of the villain, Anwar (later re-named "Zigzag"),[8] originally assigned to Kenneth Williams. Sir Anthony Quayle was cast as King Nod. Price was hired to make the villain more enjoyable for Williams, as he was a great fan of Vincent Price's work and ZigZag was based on two people Williams hated.[7]

Nasruddin becomes The Thief and the Cobbler

Idries Shah demanded 50% of the profits from the film, and Idries Shah’s sister, who had done some of the translations for the Nasrudin book claimed that she owned the stories.[5][9] As a result, Williams had a falling-out with the Shah family in 1972, Paramount withdrew a deal that they'd been negotiating,[9] and Williams was forced to abandon the script.

In a promotional booklet released in 1973, Williams made an announcement about the status of his project:

“ Nasruddin was found to be too verbal and not suitable for animation, therefore Nasruddin as a character and the Nasruddin stories were dropped as a project. However, the many years work spent on painstaking research into the beauty of Oriental art has been retained. Loosely based on elements in the Arabian Nights stories, an entirely new and original film entitled The Thief and The Cobbler is now the main project of the Williams Studio. Therefore any publicity references to the old character of Nasruddin are now obsolete.[8] ” The publicity release, however, failed to mention that almost all of the Nasruddin footage, characters and scenes that did not have Nasruddin himself were retained. While the story's focus and tone was shifted, several characters, including Anwar/Zigzag, were all carried over to the "new" film, which Williams was promising as a "100 minute Panavision animated epic feature film with a hand-drawn cast of thousands."[8]

By 1973, Williams had co-written a new script with his wife Margaret French. Nasruddin was replaced by a cobbler named Tack. The characters were renamed at this point. In the Nasruddin years, Phido's original name was "Brutay", making Zigzag's last words "You, too, Phido?" a reference to the famous "Et tu, Brute?". Zigzag speaks mostly in rhyme throughout the entire film, while the other characters speak normally (the thief and Tack do not speak at all, except for one line for Tack at the very end, voiced by Sean Connery). In an interview with John Canemaker in the Feb. 1976 issue of Millimeter, Richard Williams stated that "The Thief is not following the Disney route." He went on to state that the film would be "the first animated film with a real plot that locks together like a detective story at the end," and that, with its two mute main characters, Thief was essentially "a silent movie with a lot of sound."[8]

Prolonged production (1972-1986)

Williams worked on the production as a side project in-between various TV commercial, TV special, and feature film title assignments, such as the 1977 feature Raggedy Ann & Andy: A Musical Adventure. Because he had no money to have a full team working on the film, and due to the film being a "giant epic", production dragged for decades.[6] In order to save money, scenes were kept in pencil stage without putting it into colour, as advised by Dick Purdom: "Work on paper! Don’t put it in colour. Don’t spend on special effects. Don’t do camera-work, tracing or painting …. just do the rough drawings!”[10]

Upon seeing Disney's The Jungle Book,[2] Richard Williams realised that he was not very skilled in animating and that he needed to actually learn the craft, if he wanted to hold the audience's interest:

“ I was a graphic artist in animation … thought I was ever so clever, until one day I realized I didn’t know a damned thing. I couldn’t suspend disbelief for more than 15 to 20 minutes. I thought I had better go and study ‘how you do it’. So we did … and it was a nasty shock to realize when you thought you were wonderful and were covered with awards, that you didn’t know how to do it, at all.[10] ” Williams thus decided to get several animator veterans from the golden age of animation, such as Art Babbitt, Ken Harris, Emery Hawkins and Grim Natwick to work on the film in his studio in London and teach him their knowledge and skill of animation:[7][11] Williams learned also from Milt Kahl, Frank Thomas, Ollie Johnston and Ken Anderson at Disney, to whom he made yearly visits.[12] Williams would later pass their knowledge to the new generation of animators.[2]

As years passed, the project became more ambitious. Williams said that "The idea is to make the best animated film that has ever been made - there really is no reason why not."[6] The film features very detailed and complex animation, such as scenes where the entire picture is animated by hand to move in three dimensions: this was achieved without computer-generated imagery.[1][3][5] Additionally, almost the whole film has been animated "on ones", meaning that the animation runs at full 24 frames per second, as opposed to the cheaper and more common animation "on twos" at twelve frames per second.[1][5][9]

Because Ken Harris was a very fast animator, and the film had no plot since the removal of the Nasruddin character and before the script rewrite, Williams had to invent several scenes for the Thief character (which was designed as a caricature of Williams) in order to keep Harris working. Another artist hired was illustrator Errol Le Cain, who did inspirational paintings and backgrounds, setting the style for the film.[13] During the decades that the film was being made, the characters were redesigned several times, and scenes were reanimated. The Mad Holy Old Witch was designed as a caricature of animator Grim Natwick,[14] by whom she was animated. Animation drawings of the Mad Holy Old Witch were later used in Richard Williams' 2000 book The Animator's Survival Kit.

In 1978, a prince from Saudi Arabia named Mohammed Feisal became interested in The Thief and agreed to fund ten minutes as a test, with the budget of $100,000. Williams chose the complex War Machine scene for the test. He missed two deadlines, and the scene was completed in the end of 1979 for $250,000. Prince Feisal flew to London for a screening, and although the finished scene was very impressive,[9] he backed out of the production because of missed deadlines and budgetary overruns.[5]

The Thief gains financial backing

In 1986, Williams met producer Jake Eberts, who began funding the production through his Allied Filmmakers company and, according to the August 30, 1995 edition of The Los Angeles Times, eventually provided $10 million of the film's $28 million budget.[8][15] Allied's distribution and sales partner, Majestic Films, began promoting the film in industry trades, under the working title Once....

In the 1980s, Williams put together a 12-minute sample reel of The Thief, which he showed to his friend and animation mentor Milt Kahl in San Francisco. After hearing about the rather enthusiastic reaction the screening of "The Thief", Robert Zemeckis and Steven Spielberg decided to take a look for themselves and were so impressed that they asked Williams to direct the animation of Who Framed Roger Rabbit.[1][5][9][16] Williams agreed in order to get financing for The Thief and the Cobbler and get it finally finished. Disney and Spielberg told Williams that in return for doing Roger Rabbit, they would help distribute his film.[17] Roger Rabbit was released in 1988, and became a blockbuster. Williams won two Oscars for his animation. The success of Roger Rabbit proved that Williams could work within a studio structure and turn out high-quality animation on time and within budget.[8]

Because of his success, Williams received funding and a distribution deal for The Thief and the Cobbler with Warner Bros. Pictures: They signed a negative pickup deal in 1988. Williams also got some money from Japanese investors.[5][9]

Beginning on full production (1989-1992)

With the new funding, the film finally got into full production in 1989. Williams scoured the art schools of Europe and Canada to find talented artists.[16] It was at this point, with almost all of the original animators either dead or having long since moved on to other projects, that full-scale production on the film began, mostly with a new, younger team of animators, including Richard Williams's son Alexander Williams. In a 1988 interview with Jerry Beck, Williams stated that he had two and a half hours of pencil tests for Thief and that he had not storyboarded the film as he found such a method too controlling.[8]

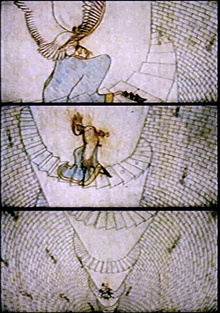

As an example of Williams' animation quality, several scenes were animated by hand to move in three dimensions - this was achieved without CGI. This uncolourised scene exists only in Williams' original, unfinished version of the film and was cut along with many other ones in the two released versions.

Discipline was harsh. "He fired hundreds of people. There's a list as long as your arm of people fired by Dick. It was a regular event." cameraman John Letherbarrow recalls,"There was one guy who got fired on the doorstep." Williams was just as hard on himself: "He was the first person in the morning and the last one out at night," recalls animator Roger Visard.[16]

At this time Eberts encouraged Williams to make changes to the script. The prince Bubba subplot was removed, resulting in the loss of the following characters: Princess Mee-Mee (Yum-Yum's twin sister), and Prince Bubba, who had been turned into an ogre.[18] Some of Grim Natwick's animation of the Witch had to be discarded.[8]

Funders pressured Williams to make finished scenes of the main characters for a marketing trailer. The final designs were made for the characters at this time. The shot of Princess Yum-Yum in the trailer was traced from a live action film - her design was slightly changed for the rest of the film, resulting her to be slightly "off-model" in the scene.[18] Tack was modeled after silent film stars Charlie Chaplin and Harry Langdon. Movement 1 of the symphonic suite Scheherazade by Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov was used in the trailer.

In Richard Williams' script for the film, the climax was even longer (and slightly different) than in the workprint or final films: After the collapse of the War Machine, Zigzag, at Mighty One-Eye's goading, conjures a larger-than-life Oriental dragon (which dwarfed even the War Machine), which is about to flatten Tack, who once again trusts on his tack to bring down the dragon, revealing it to be nothing more than an inflatable balloon (filled with acrid fumes, which permeates the atmosphere and makes everyone cough, even Mighty One-Eye; That can still be heard in the workprint). Enraged, Mighty One-Eye is going to kill a frightened Zigzag just before meeting his own doom (the same one as in the workprint), but Zigzag is pursued by Tack, Yum Yum and the Brigands and hides from them just before inadvertently meeting his own doom (also in the workprint). Although there were some production designs of the scene with the Oriental dragon, it was never made, as it was found to be too difficult to animate.[16]

Richard Williams loses control of the film (1992)

The film was not finished by the 1991 deadline that Warner imposed upon Williams;[16] the film had approximately 10 to 15 minutes of screen time to complete, which at William's rate was estimated to take several months to complete.[3][5] Meanwhile Walt Disney Feature Animation had begun work on Aladdin, a film which (coincidentally or not) bore striking resemblances in tone and style to The Thief and the Cobbler; for example, the character Zigzag from Thief shares many physical characteristics with both Aladdin's villain, Jafar, and its Genie.[19][20]

Seeing it as potential competition to Thief's commercial viability, television animation producer Fred Calvert was asked to do a detailed analysis of the production status in early 1991.[3] He had already traveled to Williams' London studio several times to check on the progress of the film, and his conclusion was that Williams was "woefully behind schedule and way over budget".[8] Williams did indeed have a script, according to Calvert, but "he wasn't following it faithfully." Williams was asked to show the investors a rough copy of the film with the remaining scenes filled in with storyboards in order to establish the film's narrative.[5][16] Williams had avoided storyboards up to this point, but within two weeks he had done what the investors had asked. "They had to twist his fingers to do storyboards, he refused to do them."[16] Williams made a workprint which combined finished footage, pencil test and storyboards which covered the 10 to 15 minutes left to finish.[3] This workprint has been bootlegged, and copies exist.[3][16]

The workprint was shown to Warner. This rough version of the film was not well received; by September 1992, Warner had lost confidence and backed out of the project, and the Completion Bond company had seized control of the film.[5][16] According to Alex Williams, executive producer Jake Eberts also abandoned the project;[3] his comments on record claiming that the altered versions were superior to Williams' version indicate that Eberts had also lost confidence in Williams. Additionally, according to Richard Williams himself, the production had lost a source of funding when Japanese investors pulled out due to the recession following the Japanese asset price bubble.[21]

Production under Fred Calvert (1992-1993)

Fred Calvert was assigned by the Completion Bond Company to finish the film as cheaply and quickly as possible, an assignment he tried to avoid. When the arrangements with another producer fell through, he took the job "somewhat under protest."[8] "I really didn't want to do it," Calvert said, "but if I didn't do it, it would have been given off to the lowest bidder. I took it as a way to try and preserve something and at least get the thing on the screen and let it be seen."[15] Sue Shakespeare of Creative Capers Entertainment had previously offered to solve story problems with Terry Gilliam and Williams, and proposed to allow Williams to finish the film under her supervision. However, her bid was rejected by Completion Bond in favor of a cheaper one by Calvert.[22]

In the process, Calvert completely re-edited the film. Much of Williams's finished footage was deleted from the final release print because of the repetitive nature of the scenes.

"We took it and re-structured it as best we could and brought in a couple of writers and went back into all of Richard Williams' work, some that he wasn't using and found it marvelous...we tried to use as much of his footage as possible." "We hated to see of all this beautiful animation hit the cutting room floor, but that was the only way we could make a story out of it. One of the problems, there were a number of these situations...in the script, there might be two or three sentences describing the Thief going up a drain pipe. But what he animated on the screen was five minutes up and down that pipe which would ordinarily be five pages of script...These were the kind of imbalances that were happening. He [Richard Williams] was kind of Rube Goldberg-ing his way through. I don't think he was able to step back and look at the whole thing as a story."Some of the deleted scenes ended up as being displayed during the end credits. Also, Steve Lively was brought in to record a voice and narration for the previously mute character of Tack, and several other characters that already had vocal tracks prepared for them were re-voiced. While having a speaking hero wasn't Calvert's choice, he felt it was a logical decision in order to tell the story.[8] Four songs were added: She is More, Am I Feeling Love?, Bom, Bom, Bom, Beem, Bom and It's So Amazing. Adult content was also toned down: In the scene where the dying messenger warns the king, the spike (from the flagpole) sticking out of his chest was removed. The same thing goes for any audio (or reference) of the Maiden from Mombassa.

It took Calvert 18 months to finish the film.[16] The new scenes were produced on a very low budget, with the animation being produced by freelance animators in Los Angeles (some from Kroyer Films, who is also credited), former Williams animators at Premier Films in London, and Don Bluth animators[16] working under Gary Goldman in Ireland.[8] The ink and paint work was subcontracted to Wang Film Productions in Taiwan, who themselves outsourced most of the work to their satellite studio in Thailand; additional ink and paint work was done at Varga Studio in Hungary and at The Magic Brush in Hollywood. Some work was also done in Korea.[23] The end results have been widely seen as "obviously and pitifully inferior" in quality to Williams's original scenes;[1][3][24] the primary concern was to complete the film in as little time and for as little money as possible.[citation needed]

"[Williams is] an incredible animator, though. Incredible. One of the biggest problems we had was trying our desperate best, where we had brand new footage, to come up to the level of quality that he had set."Releases

After the film's completion, Jake Eberts' Allied Filmmakers, along with Majestic Films, reacquired the distribution rights from the Completion Bond Company.

Calvert's version of the film was distributed in Australia and South Africa as The Princess and the Cobbler. Until Miramax agreed to distribute the film, it was refused by many other American distributors . "It was a very difficult film to market, it had such a reputation," Calvert recalls. "I don't think that they were looking at it objectively."[16]

In December 1994, the Disney subsidiary Miramax bought the rights. Miramax recut the film even further[25] and released their own version in the U.S., Arabian Knight,, featuring newly-written dialogue by Eric Gilliland, Michael Hitchcock, and Gary Glasberg, and all-star voice cast that was added several months before the film's release. The voice cast consists of Matthew Broderick as Tack and Jonathan Winters as the Thief. Tack and the Thief's dialogue was added over nearly every scene of the film; Williams' version had been largely dialogue-less. The character of the Old Witch was entirely removed (save for a few lines of dialogue and ghost-like image), as was most of a climactic battle sequence.

Arabian Knight was quietly released by Miramax on August 25, 1995. It opened on 510 screens,[8] and grossed $319,723[15][16] (on an estimated budget of $24 million) during its theatrical run.

Ironically, to this day the film has never been released in any form in the United Kingdom, where the majority of the production took place.

Home media

The Miramax (1995) version of the film was finally released on VHS on February 18, 1997 as The Thief and the Cobbler (originally released in theatres as Arabian Knight).[3] A widescreen laserdisc was also released, and a Japanese-dubbed widescreen DVD of the 1995 release.

The first time that the Miramax version of the film appeared on DVD, was in Canada in 2001 as a giveaway promotion in packages of Kellogg's Froot Loops cereal. This pan and scan DVD was released through Alliance Atlantis which distributes many of Miramax's films in Canada. It came in a paper sleeve and had no special features, other than the choice of English or French language tracks.[28]

The "Princess and the Cobbler" edit was released on a pan and scan DVD in Australia in 2003 by Magna Pacific, according to some sites; additional features on the DVD are unknown.

The Miramax version was first released commercially on DVD on March 8, 2005, in pan-and-scan format. This DVD was re-released by The Weinstein Company on November 21, 2006. Although the information supplied to retailers such as Amazon.com by retail distribution companies said that it would be a widescreen "collector's edition", this DVD was in fact the old 2005 pan-and-scan DVD in fancy packaging. The 2006 DVD has been found by most reviewers to be unsatisfactory, with the image quality being compared to "a VHS/Beta tape rather than a DVD... and one that’s seen better days".[29][30] The Digital Bits gave it an award for being the worst standard-edition DVD of 2006.[31] Although the second DVD of the Miramax version of this film was the same DVD as the first one; this DVD featured trailers and promos for Weinstein Company-produced family films, including Hoodwinked and Arthur and the Invisibles.

The Miramax version was re-released on DVD on May 3, 2011 by Echo Bridge Home Entertainment, a independent DVD distributor who recently made a deal with Miramax to release 251 titles from the Miramax library.[1]

Reception

Although the film's executive producer Jake Eberts found that "It was significantly enhanced and changed by Miramax after Miramax stepped in and acquired the domestic [distribution] rights,"[15] the Miramax version of the film was a commercial failure.[25] Critical response to this version was negative. Film website Rotten Tomatoes, which compiles reviews from a wide range of critics, gives the film a score of 40%.[32] Carn James of New York Times criticised the songs sung by the princess, calling the lyrics "horrible" and the melodies "forgettable", though he did praise Williams' animation as "among the most glorious and lively ever created".[20] Alex Williams, son of the original director, criticised changes made by Calvert and Miramax, called the finished film "more or less unwatchable" and found it "hard [...] to find the spirit of the film as it was originally conceived".[3] Similarly, Jerry Beck felt that the added voiceovers of Jonathan Winters and Matthew Broderick were unnecessary and unfunny, and that Fred Calvert's new footage didn't meet the standards of the original Williams scenes.[25] However, in 2003, the Online Film Critics Society ranked the film as the 81st greatest animated film of all time. In addition, the film won the 1995 Academy of Family Films Award.[33] Richard Williams apparently refuses to talk about the film to anyone, however, in 2010, he did speak about The Thief and the Cobbler in an interview about his upcoming silent animation called Circus Drawings.[34][35][36]

Influence

The Secret of Kells, a 2009 animated film that based its style on traditional Irish art, had The Thief and the Cobbler as one of its main inspirations. In the words of Kells co-director Tomm Moore, "Some friends in college and I were inspired by Richard Williams unfinished masterpiece The Thief and the Cobbler and the Disney movie Mulan, which took indigenous traditional art as the starting point for a beautiful style of 2D animation. I felt that something similar could be done with Irish art."[37]

Restoration attempts

Several low-quality video copies of Richard Williams' workprint have been shared among animation fans and professionals.[3][16][25] The problem in creating a high-quality restoration is that after the Completion Bond Company had finished the film, many scenes by Williams that were removed disappeared - many of these had fallen into the hands of private parties.[23] Before losing control of the film, Williams had originally kept all artwork safe in a fireproof basement.[6] Additionally, there are legal problems with Miramax.[23]

At the 2000 Annecy Festival, Williams showed Walt Disney Feature Animation head Roy E. Disney a faded workprint of The Thief, which Disney liked. With William's full support,[25] Roy Disney began a project to restore The Thief and the Cobbler to as close to Williams' original intent as possible.[23] He sought out original pencil tests and completed footage, much of which was by this time in the possession of various animators and film collectors. The restored work would have been released on a special DVD and given a limited run in theatres once finished.[23] Roy Disney left the Walt Disney Company in November 2003, and the Thief and the Cobbler restoration project was put on hold.[25]

In 2006, a fan of Richard Williams' work named Garrett Gilchrist created a non-profit fan restoration of William's workprint, named The Thief and the Cobbler: The Recobbled Cut. It was done in as high quality as possible by combining available sources, such as a bootleg copy of Williams' workprint and better-quality footage from DVD and VHS copies of the released versions. This edit was much supported by numerous people who had worked on the film (with the exception of Richard Williams himself, who wishes not to have anything to do with the film anymore), including Roy Naisbitt, Alex Williams, Andreas Wessel-Therhorn, Tony White, Holger Leihe, Steve Evangelatos, Greg Duffell, Jerry Verschoor and Beth Hannan, many of whom lent rare material for the project. Some minor changes were made to "make it feel more like a finished film", like adding more music and replacing storyboards with some of Fred Calvert's animation.[24] This edit gained positive reviews on the Internet: Twichfilm.net called it "the best and most important 'fan edit' ever made".[34]

See also

- List of animated feature films

- History of British animation

- Film modification

- Re-edited film

Other animated movies with long production histories

- The Overcoat, an upcoming Russian animated film, in production since 1981

- Le Roi et l'oiseau, a French animated film, produced in two parts (1948–52, 1967–80), initially released in recut form, eventually finished as per director’s wishes

References

- ^ a b c d e f Briney, Daniel. 21 August 2001. "The Thief and the Cobbler: How the Best Was Lost, 1968-1995" at CultureCartel. Accessed 12 November 2006.

- ^ a b c Wolters, Johannes (Tuesday, January 13, 2009). "Getting Animated About Williams' Masterclass". Animation World Network. http://www.awn.com/articles/reviews/getting-animated-about-williams-masterclass/page/1%2C1. Retrieved 21 November 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Williams, Alex (March 1997). "The Thief And The Cobbler". Animation World Magazine. http://www.awn.com/mag/issue1.12/articles/williams1.12.html. Retrieved 2009-05-09.

- ^ Robertson, Patrick. Das neue Guinness Buch Film. Frankfurt (1993), p 122, cited by J. Trimborn, p 204

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Summer, Edward (1996). "The Animator Who Never Gave Up -- The Unmaking of a Masterpiece.". Films In Review. http://www.vmresource.com/thief/edsummer.html.

- ^ a b c d e Tom Gutteridge (director) (1988). I Drew Roger Rabbit (TV featurette).

- ^ a b c d The Thief who never gave up (TV documentary). United Kingdom: Thames Television. 1982.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Dobbs, Mike (1996). "An Arabian Knight-mare". Animato! (35). http://groups.google.com/group/rec.arts.animation/msg/e7fd132fc8aa689f.

- ^ a b c d e f Grant, John (2006). Animated Movies Facts, Figures & Fun. pp. 47–49. ISBN 1904332528.

- ^ a b Clark, Ken (1984). "Animated Comment – Ken Clark chats with Richard Williams". Animator magazine (11). http://www.animatormag.com/archive/issue-11/issue-11-page-8/.

- ^ The Los Angeles Times. May 20. http://articles.latimes.com/1992-05-20/entertainment/ca-165_1_warner-bros?pg=1.[dead link]

- ^ Cohen, Karl (Friday, February 15, 2002). "The Animator's Survival Kit: The Most Valuable How To Animate Book You Will Ever Want To Own". Animation World Network. http://www.awn.com/articles/reviews/animators-survival-kit-most-valuable-how-animate-book-you-will-ever-want-own. Retrieved 22 November 2010.

- ^ Leihe, Holger (December 12, 2007). "Cobbler and Errol". THE THIEF. self-published. http://thethief1.blogspot.com/2007/12/cobbler-and-errol.html. Retrieved 20 August 2009.

- ^ Leihe, Holger (January 18, 2008). "Witch". THE THIEF. self-published. http://thethief1.blogspot.com/2008/01/witch_18.html. Retrieved 20 August 2009.

- ^ a b c d Welkos, Robert W. (August 30). "How This 'Thief' Became a 'Knight'". The Los Angeles Times. http://articles.latimes.com/1995-08-30/entertainment/ca-40326_1_richard-williams. Retrieved May 25, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Lurio, Eric. "Arabian Knightmare". http://www.vmresource.com/thief/lurio.html. Retrieved 2009-04-09.

- ^ James B. Stewart (2005). DisneyWar. New York City: Simon & Schuster. pp. 87. ISBN 0-684-80993-1.

- ^ a b Leihe, Holger (February 14, 2008). "Throne Room, Part 1". THE THIEF. self-published. http://thethief1.blogspot.com/2008/02/throne-room-part-1.html. Retrieved 20 August 2009.

- ^ "The Thief and the Cobbler review". DVD snapshot. http://www.dvdsnapshot.com/January07Review/ThiefAndCobbler.html.

- ^ a b c James, Caryn (1995-08-26). "The Thief and the Cobbler NY Times review". The New York Times. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=990CE6DE153DF935A1575BC0A963958260.

- ^ Williams, Richard (2008-11-02). ASIFA-San Francisco benefit appearance, Balboa Theater, San Francisco, California.

- ^ "Letters to the Editor". ANimation World Magazine. April 1997. http://www.awn.com/mag/issue2.1/articles/letters2.1.html.

- ^ a b c d e f DeMott, Rick (August 18, 2000). "Disney To Restore The Thief And The Cobbler To Original Version". Animation World Network. http://www.awn.com/news/films/disney-restore-thief-and-cobbler-original-version. Retrieved 21 November 2009.

- ^ a b "Thief and the Cobbler: The Recobbled Cut". Cartoon Brew. 2006-06-24. http://www.cartoonbrew.com/old-brew/thief-and-the-cobbler-the-recobbled-cut.html. Retrieved 2009-05-09.

- ^ a b c d e f g Beck, Jerry (2005). "Arabian Knight". The Animated Movie Guide. Chicago Review Press. pp. 23–24. ISBN 1556525915.

- ^ a b McCracken, Harry (1995). "The Theft of the Thief". fps Magazine. http://www.harrymccracken.com/lastword.htm.

- ^ "The Best Animated Movie You've Never Heard Of". TV Guide. 2006-11-28. http://movies.tvguide.com/movie-news/best-animated-movie-7953.aspx. Retrieved November 21, 2009.

- ^ Garrett Gilchrist (2006). About this film (DVD). self-published.

- ^ DVDFILE.com

- ^ Moriarty’s DVD Blog! A Word About That New THIEF & THE COBBLER Disc - Ain't It Cool News: The best in movie, TV, DVD, and comic book news

- ^ King Bitsy: Other DVD Awards for 2006

- ^ "Tomatometer for The Thief and the Cobbler". Rotten Tomatoes. http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/thief_and_the_cobbler/. Retrieved 2007-01-09.

- ^ "Top 100 Animated Features of All Time". Online Film Critics Society. http://ofcs.rottentomatoes.com/pages/pr/top100animated. Retrieved 2007-01-09.

- ^ a b Brown, Todd (2006-06-04). "Richard Williams’ Lost Life’s Work Restored By One Obsessive Fan ...". Twitch. http://twitchfilm.net/site/view/richard-williams-lost-lifes-work-restored-by-one-obsessive-fan/. Retrieved 2009-05-11.

- ^ "onehugeeye » Richard Williams". http://www.onehugeeye.com/richard-williams/. Retrieved 11 March 2011.

- ^ Deneroff, Harvey (20 October 2010). "Richard Williams’ Circus Drawings’ Silent Premiere". http://deneroff.com/blog/2010/10/20/richard-williams-circus-drawings-silent-premiere/. Retrieved 11 March 2011.

- ^ Cohen, Karl (Tuesday, March 16, 2010). "The Secret of Kells - What is this Remarkable Animated Feature?". Animation World Network. http://www.awn.com/articles/2d/secret-kells-what-remarkable-animated-feature/page/1%2C1.

External links

- The Thief and the Cobbler at the Internet Movie Database

- Eddie Bowers' The Thief and the Cobbler Page – A website about Richard Williams' The Thief and the Cobbler with articles, clips from the workprint, pictures, and the history of the film.

- The Thief Blog - A blog where people who worked on the film recount their memories of the film's production.

Films directed The Little Island · A Christmas Carol · Raggedy Ann & Andy: A Musical Adventure · Ziggy's Gift · The Thief and the CobblerBooks written Categories:- 1993 films

- 1995 films

- Animated features released by Miramax Films

- Baghdad in fiction

- British animated films

- Fan edits

- Fantasy adventure films

- Fictional professional thieves

- Films directed by Richard Williams

- Films set in Iraq

- Films shot in CinemaScope

- Lost films

- Miramax Films films

- Unfinished films

- Art films

- Works based on One Thousand and One Nights

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.