- British Hong Kong

-

Hong Kong

香港British colony ←

←

1841–1941

1945–1997 →

→

→

→

Flag (1959–1997) Coat of arms (1959–1997) Motto

"Dieu et mon droit" (French)

"God and my right"Anthem

God Save the King/QueenLocation of Hong Kong Capital Victoria City Language(s) English, Chinese Government Crown colony

(1843–1941, 1945–1981)

British Dependent Territory

(1981–1997)Monarch - 1841–1901 Victoria (first) - 1952–1997 Elizabeth II (last) Governor - 1843–1844 Henry Pottinger (first) - 1992–1997 Chris Patten (last) Colonial/Chief Secretary1 - 1843–1844 John Morrison (first) - 1993–1997 Anson Chan (last) Legislature Legislative Council Historical era New Imperialism {{#if:|| {{#ifeq:0|1|[[Category: }}

- Convention of Chuenpee 20 January 1841 - Treaty of Nanking 29 August 1842 - Convention of Peking 24 October 1860 - Second Convention of Peking 9 June 1898 - Battle of Hong Kong December 1941 - Handover to PRC 30 June 1997 Area - 1848 80.4 km2 (31 sq mi) - 1901 1,042 km2 (402 sq mi) Population - 1848 est. 24,000 Density 298.5 /km2 (773.1 /sq mi) - 1901 est. 283,978 Density 272.5 /km2 (705.9 /sq mi) - 1945 est. 750,000 Density 719.8 /km2 (1,864.2 /sq mi) - 1995 est. 6,300,000 Density 6,046.1 /km2 (15,659.2 /sq mi) Currency Hong Kong dollar (since 1937) 1 The title changed from "Colonial Secretary" to "Chief Secretary" in 1976. British Hong Kong refers to Hong Kong as a Crown colony and later, a British dependent territory under British administration from 1841 to 1997.

Contents

History

Colonial establishment

Further information: History of Hong Kong (1800s–1930s)In 1836, the Chinese government undertook a major policy review of the opium trade. Lin Zexu volunteered to take on the task of suppressing opium. In March 1839, he became Special Imperial Commissioner in Canton, where he ordered the foreign traders to surrender their opium stock. He confined the British to the Canton Factories and cut off their supplies. Chief Superintendent of Trade, Charles Elliot, complied with Lin's demands in order to secure a safe exit for the British, with the costs involved to be resolved between the two governments. When Elliot promised that the British government would pay for their opium stock, the merchants surrendered their 20,283 chests of opium, which were destroyed in public.[1]

In September 1839, the British Cabinet decided that the Chinese should be made to pay for the destruction of British property by the threat or use of force. An expeditionary force was placed under Elliot and his cousin George Elliot as joint plenipotentiaries in 1840. Foreign Secretary Lord Palmerston stressed to the Chinese government that the British government did not question China's right to prohibit opium, but it objected to the way this was handled.[1] He viewed the sudden strict enforcement as laying a trap for the foreign traders, and the confinement of the British with supplies cut off was tantamount to starving them into submission or death. He instructed the Elliot cousins to occupy one of the Chusan islands, to present a letter from himself to a Chinese official for the Emperor, then to proceed to the Gulf of Bohai for a treaty, and if the Chinese resisted, blockade the key ports of the Yangtze and Yellow rivers.[2] Palmerston demanded a territorial base in Chusan for trade so that British merchants "may not be subject to the arbitrary caprice either of the Government of Peking, or its local Authorities at the Sea-Ports of the Empire".[3]

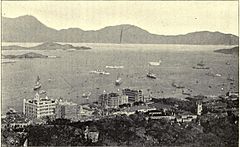

In 1841, Elliot negotiated with Lin's successor, Qishan, in the Convention of Chuenpee during the First Opium War. On 20 January, Elliot announced "the conclusion of preliminary arrangements", which included the cession of Hong Kong Island and its harbour to the British crown.[4] On 26 January, the Union Flag was raised on Hong Kong, and Commodore James Bremer, commander-in-chief of the British forces in China, took formal possession of the island at Possession Point.[5] Elliot chose Hong Kong instead of Chusan because he believed a settlement further east would cause an "indefinite protraction of hostilities", whereas Hong Kong's harbour was a valuable base for the British trading community in Canton.[6] On 29 August 1842, the cession was formally ratified in the Treaty of Nanking, which ceded Hong Kong "in perpetuity" to Britain.

Growth and expansion

The treaty failed to satisfy British expectations of a major expansion of trade and profit, which led to increasing pressure for a revision of the terms.[7] In October 1856, Chinese authorities in Canton detained the Arrow, a Chinese-owned ship registered in Hong Kong to enjoy protection of the British flag. The Consul in Canton, Harry Parkes, claimed the hauling down of the flag and arrest of the crew were "an insult of very grave character". Parkes and Hong Kong Governor John Bowring seized the incident to pursue a forward policy. In March 1857, Palmerston appointed James Bruce as Plenipotentiary with the aim of securing a new and satisfactory treaty. A French expeditionary force joined the British to avenge the execution of French missionary Auguste Chapdelaine in 1856.[8] In 1860, the capture of the Taku Forts and occupation of Beijing led to the Treaty of Tientsin and Convention of Peking. In the Treaty of Tientsin, the Chinese accepted British demands to open more ports, navigate the Yangtze River, legalise the opium trade, and have diplomatic representation in Beijing. During the conflict, the British occupied the Kowloon Peninsula, where the flat land was valuable training and resting ground. The area in what is now south of Boundary Street and Stonecutters Island was ceded in the Convention of Peking.[9]

In 1898, the British sought to extend Hong Kong for defence. After negotiations began in April 1898, with the British Minister in Beijing, Claude MacDonald, representing Britain, and diplomat Li Hongzhang leading the Chinese, the Second Convention of Peking was signed on 9 June. This granted a 99-year lease of the rest of Kowloon south of the Shenzhen River and 230 islands, which became known as the New Territories. The British formally took possession on 16 April 1899.[10]

Japanese occupation

In 1941, during the Second World War, the British reached an agreement with the Chinese government under Chiang Kai-shek that if Japan attacked Hong Kong, the Chinese army would attack the Japanese from the rear to relieve pressure on the British garrison. On 8 December, the Battle of Hong Kong began when Japanese air bombers effectively destroyed British air power in one attack.[11] Two days later, the Japanese breached the Gin Drinkers Line in the New Territories. The British commander, Major-General Christopher Maltby, concluded that the island could not be defended for long unless he withdrew his brigade from the mainland. On 18 December, the Japanese crossed Victoria Harbour.[12] By 25 December, organised defence was reduced into pockets of resistance. Maltby recommended a surrender to Governor Mark Young, who accepted his advice to reduce further losses. A day after the invasion, Chiang ordered three corps under General Yu Hanmou to march towards Hong Kong. The plan was to launch a New Year's Day attack on the Japanese in the Canton region, but before the Chinese infantry could attack, the Japanese had broken Hong Kong's defences. The British casualties were 2,232 killed or missing and 2,300 wounded. The Japanese reported 1,996 killed and 6,000 wounded.[13]

Restoration of British rule

On 14 August 1945, when Japan announced its unconditional surrender, the British formed a naval task group to sail towards Hong Kong.[14] On 1 September, Rear-Admiral Cecil Harcourt proclaimed a military administration with himself as its head. He formally accepted the Japanese surrender on 16 September in Government House.[15] Governor Mark Young pursued political reform, believing that given the Chinese government's determination to recover Hong Kong, the only way to keep the colony British was to make the local inhabitants want to do so. He believed this could be done by making local inhabitants participate in politics.[16]

Handover to China

Main article: Transfer of sovereignty over Hong KongGovernment

In January 1841, when Elliot declared Hong Kong's cession to Britain, he proclaimed that the government shall devolve upon the office of Chief Superintendent of British Trade in China. He issued a proclamation with Bremer to the inhabitants on 1 February, declaring that they "are hereby promised protection, in her majesty's gracious name, against all enemies whatever; and they are further secured in the free exercise of their religious rites, ceremonies, and social customs; and in the enjoyment of their lawful private property and interests."[4] Elliot declared that Chinese natives would be governed under Chinese laws (excluding torture), and that British subjects and foreigners would fall under British law.[4] However, London decided that English law should prevail.[17]

The Letters Patent of 5 April 1843 defined the constitutional structure of Hong Kong as a Crown colony and the Royal Instructions detailed how the region should be governed and organised. The Letters Patent prescribed a Governor as head of government, and both the Executive Council and Legislative Council being advisors to the governor.[18] The administrative civil service of the colony was led by a Colonial Secretary (later Chief Secretary), who was deputy to the governor.

In 1861, Governor Hercules Robinson introduced the Hong Kong Cadetship, which recruited young graduates from Britain to learn Cantonese and written Chinese for two years, before deploying them on a fast track to the civil service. Cadet officers gradually formed the backbone of the civil administration. After the Second World War, ethnic Chinese were allowed into the service, followed by women. Cadets were renamed Administrative Officers in the 1950s, and they remained the elite of the civil service during British rule.[19]

Economy

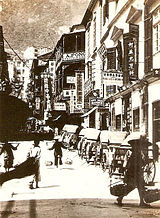

The stability, security, and predictability of British law and government enabled Hong Kong to flourish as a centre for international trade.[20] In the colony's first decade, the revenue from the opium trade was a key source of government funds. The importance of opium reduced over time, but the colonial government were dependent on its revenues until the Japanese occupation in 1941.[20] Although the largest businesses in the early colony were operated by British, American, and other expatriates, Chinese workers provided the bulk of the manpower to build a new port city.[21]

Notes

- ^ a b Tsang 2004, pp. 9–10

- ^ Tsang 2004, p. 11

- ^ Tsang 2004, p. 21

- ^ a b c The Chinese Repository. Volume 10. pp. 63–64.

- ^ Belcher, Edward (1843). Narrative of a Voyage Round the World. Volume 2. p. 148.

- ^ Tsang 2004, pp. 11, 21

- ^ Tsang 2004, p. 29

- ^ Tsang 2004, pp. 32–33

- ^ Tsang 2004, pp. 33, 35

- ^ Tsang 2004, pp. 38–41

- ^ Tsang 2004, p. 121

- ^ Tsang 2004, p. 122

- ^ Tsang 2004, pp. 123–124

- ^ Tsang 2004, p. 133

- ^ Tsang 2004, p. 138

- ^ Tsang 2004, pp. 143–144

- ^ Tsang 2004, p. 23

- ^ Tsang 2004, pp.18–19

- ^ Tsang 2004, pp. 25–26

- ^ a b Tsang 2004, p. 57

- ^ Tsang 2004, p. 58

References

- Tsang, Steve (2004). A Modern History of Hong Kong. I. B. Tauris. ISBN 1845114191.

British Empire and Commonwealth of Nations Legend

Current territory · Former territory

* now a Commonwealth realm · now a member of the Commonwealth of NationsEurope18th century

1708–1757 Minorca

since 1713 Gibraltar

1763–1782 Minorca

1798–1802 Minorca19th century

1800–1964 Malta

1807–1890 Heligoland

1809–1864 Ionian Islands20th century

1921-1937 Irish Free StateNorth America17th century

1583–1907 Newfoundland

1607–1776 Virginia

since 1619 Bermuda

1620–1691 Plymouth Colony

1629–1691 Massachusetts Bay Colony

1632–1776 Maryland

1636–1776 Connecticut

1636–1776 Rhode Island

1637–1662 New Haven Colony

1663–1712 Carolina

1664–1776 New York

1665–1674 and 1702-1776 New Jersey

1670–1870 Rupert's Land

1674–1702 East Jersey

1674–1702 West Jersey

1680–1776 New Hampshire

1681–1776 Pennsylvania

1686–1689 Dominion of New England

1691–1776 Massachusetts18th century

1701–1776 Delaware

1712–1776 North Carolina

1712–1776 South Carolina

1713–1867 Nova Scotia

1733–1776 Georgia

1763–1873 Prince Edward Island

1763–1791 Quebec

1763–1783 East Florida

1763–1783 West Florida

1784–1867 New Brunswick

1791–1841 Lower Canada

1791–1841 Upper Canada19th century

1818–1846 Columbia District / Oregon Country1

1841–1867 Province of Canada

1849–1866 Vancouver Island

1853–1863 Colony of the Queen Charlotte Islands

1858–1866 British Columbia

1859–1870 North-Western Territory

1862–1863 Stikine Territory

1866–1871 Vancouver Island and British Columbia

1867–1931 *Dominion of Canada2

20th century

1907–1949 Dominion of Newfoundland31Occupied jointly with the United States

2In 1931, Canada and other British dominions obtained self-government through the Statute of Westminster. see Canada's name.

3Gave up self-rule in 1934, but remained a de jure Dominion until it joined Canada in 1949.Latin America and the Caribbean17th century

1605–1979 *Saint Lucia

1623–1883 Saint Kitts (*Saint Kitts & Nevis)

1624–1966 *Barbados

1625–1650 Saint Croix

1627–1979 *St. Vincent and the Grenadines

1628–1883 Nevis (*Saint Kitts & Nevis)

1629–1641 St. Andrew and Providence Islands4

since 1632 Montserrat

1632–1860 Antigua (*Antigua & Barbuda)

1643–1860 Bay Islands

since 1650 Anguilla

1651–1667 Willoughbyland (Suriname)

1655–1850 Mosquito Coast (protectorate)

1655–1962 *Jamaica

since 1666 British Virgin Islands

since 1670 Cayman Islands

1670–1973 *Bahamas

1670–1688 St. Andrew and Providence Islands4

1671–1816 Leeward Islands

18th century

1762–1974 *Grenada

1763–1978 Dominica

since 1799 Turks and Caicos Islands19th century

1831–1966 British Guiana (Guyana)

1833–1960 Windward Islands

1833–1960 Leeward Islands

1860–1981 *Antigua and Barbuda

1871–1964 British Honduras (*Belize)

1882–1983 *Saint Kitts.2C 1623 to 1700|St. Kitts and Nevis

1889–1962 Trinidad and Tobago

20th century

1958–1962 West Indies Federation4Now the San Andrés y Providencia Department of Colombia

AfricaAsiaOceania18th century

1788–1901 New South Wales19th century

1803–1901 Van Diemen's Land/Tasmania

1807–1863 Auckland Islands7

1824–1980 New Hebrides (Vanuatu)

1824–1901 Queensland

1829–1901 Swan River Colony/Western Australia

1836–1901 South Australia

since 1838 Pitcairn Islands

1841–1907 Colony of New Zealand

1851–1901 Victoria

1874–1970 Fiji8

1877–1976 British Western Pacific Territories

1884–1949 Territory of Papua

1888–1965 Cook Islands7

1889–1948 Union Islands (Tokelau)7

1892–1979 Gilbert and Ellice Islands9

1893–1978 British Solomon Islands1020th century

1900–1970 Tonga (protected state)

1900–1974 Niue7

1901–1942 *Commonwealth of Australia

1907–1953 *Dominion of New Zealand

1919–1942 Nauru

1945–1968 Nauru

1919–1949 Territory of New Guinea

1949–1975 Territory of Papua and New Guinea117Now part of the *Realm of New Zealand

8Suspended member

9Now Kiribati and *Tuvalu

10Now the *Solomon Islands

11Now *Papua New GuineaAntarctica and South Atlantic17th century

since 1659 St. Helena1219th century

since 1815 Ascension Island12

since 1816 Tristan da Cunha12

since 1833 Falkland Islands1320th century

since 1908 British Antarctic Territory14

since 1908 South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands13, 1412Since 2009 part of Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha; Ascension Island (1922—) and Tristan da Cunha (1938—) were previously dependencies of St Helena

13Occupied by Argentina during the Falklands War of April–June 1982

14Both claimed in 1908; territories formed in 1962 (British Antarctic Territory) and 1985 (South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands)Categories:- Former countries in East Asia

- Former British colonies

- States and territories established in 1841

- States and territories disestablished in 1997

- China–United Kingdom relations

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.