- Li Hongzhang

-

Li Hongzhang

李鴻章

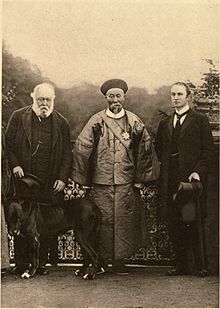

Li Hongzhang in 1896 Viceroy of Zhili and Minister of Beiyang In office

1871–1895Preceded by Zeng Guofan Succeeded by Wang Wenshao In office

1900–1901Preceded by Yu Lu Succeeded by Yuan Shikai Viceroy of Huguang In office

1867–1870Preceded by Guan Wen Succeeded by Li Hanzhang Viceroy of Liangguang In office

1899–1900Preceded by Tan Zhonglin Succeeded by Tao Mo Personal details Born February 15, 1823

Hefei, Anhui, Qing EmpireDied November 7, 1901 (aged 78)

Beijing, Qing EmpireOccupation Official, general, diplomat Li Hongzhang or Li Hung-chang (simplified Chinese: 李鸿章; traditional Chinese: 李鴻章; pinyin: Lǐ Hóngzhāng), Marquis Suyi of the First Class (Chinese: 一等肅毅侯, p Yīděng Sù Yì Hóu), GCVO, (February 15, 1823 – November 7, 1901) was a leading statesman of the late Qing Empire. He quelled several major rebellions and served in important positions of the Imperial Court, including the premier viceroyalty of Zhili.

Although he was best known in the West for his generally pro-modern stance and importance as a negotiator, Li antagonized the British with his support of Russia as a foil against Japanese expansionism in Manchuria and fell from favor with the Chinese after their loss in the 1894 Sino-Japanese War. His image in China remains controversial, with criticism on one hand for political and military mistakes and praise on the other for his success against the Taiping Rebellion, his diplomatic skills defending Chinese interests in the era of unequal treaties, and his role pioneering China's industrial and military modernization. For his life's work, the British Queen Victoria made him a Knight Grand Cross of the Royal Victorian Order.

Contents

Early life and career

Li Hongzhang was born in the village of Qunzhi (Chinese: 群治村) in Modian township (Chinese: 磨店鄉), 14 kilometers (8.7 mi) northeast of central Hefei, now the capital of Anhui province. From very early in life, he showed remarkable ability, and he became a shengyuan in the imperial examination system. In 1847, he obtained jinshi degree, the highest level in the Imperial examination system. Two years later gained admittance into the Hanlin Academy. Shortly after this the central provinces of the Empire were invaded by the Taiping rebels, and in defence of his native district he raised a regiment of militia. His service to the imperial cause attracted the attention of Zeng Guofan, the generalissimo in command.

In 1859, Li was transferred to the province of Fujian, where he was given the rank of taotai, or attendant of circuit. At Zeng's request, he fought the rebels. He formed an army called the Waigun (淮軍). He found his cause supported by the "Ever Victorious Army", which, having been raised by an American named Frederick Townsend Ward, was placed under the command of Charles George Gordon. With this support Li gained numerous victories leading to the surrender of Suzhou. For these exploits, he was made governor of Jiangsu, was decorated with an imperial yellow jacket, and was enfeoffed as an earl.

Nanjing Jinling Arsenal (金陵造局), built by Li Hongzhang in 1865, during the Self-Strengthening Movement.

Nanjing Jinling Arsenal (金陵造局), built by Li Hongzhang in 1865, during the Self-Strengthening Movement.

An incident connected with the surrender of Suzhou soured Li's relationship with Gordon. By an arrangement with Gordon, the rebel princes yielded Nanjing on condition that their lives should be spared. In spite of the agreement, Li ordered their instant execution. This breach of faith so infuriated Gordon that he seized a rifle, intending to shoot the falsifier of his word, and would have done so had Li not fled. On the suppression of the rebellion (1864), Li took up his duties as governor, but was not long allowed to remain in civil life. On the outbreak of the Nian Rebellion in Henan and Shandong (1866), he was ordered again to take to the field, and after some misadventures, he succeeded in suppressing the movement. A year later, he was appointed viceroy of Huguang, where he remained until 1870, when the Tianjin Massacre necessitated his transfer to the scene of the outrage. He was appointed to the viceroyalty of the metropolitan province of Zhili, and justified his appointment by the energy with which he suppressed all attempts to keep alive the anti-foreign sentiment among the people. For his services, he was made imperial tutor and member of the grand council of the Empire, and was decorated with many-eyed peacocks' feathers.

To his duties as viceroy were added those of the Superintendent of Trade, and from that time until his death, with a few intervals of retirement, he created the foreign policy of China. He concluded the Chefoo Convention with Sir Thomas Wade (1876), and thus ended the difficulty caused by the murder of Mr. Margary in Yunnan; he arranged treaties with Peru and the Convention of Tientsin with Japan, and he directed the Chinese policy in Korea.

Later career

On the death of the Tongzhi Emperor in 1875, he introduced a large armed force into the capital and effected a coup d'etat which placed the Guangxu Emperor on the throne under the tutelage of the two dowager empresses. In 1886, on the conclusion of the Sino-French War, he arranged a treaty with France. Li was impressed with the necessity of strengthening the empire, and while Viceroy of Zhili he raised a large well-drilled and well-armed force, and spent vast sums both in fortifying Port Arthur and the Taku forts and in increasing the navy. For years, he had watched the successful reforms effected in the Empire of Japan and had a well-founded dread of coming into conflict with that nation.

Several western sources reported that the Imperial Chinese military under the direction of Li Hongzhang acquired "Electric torpedoes", which were deployed in numerous waterways along with fortresses and numerous other modern military weapons acquired by China.[1] At the Tientsin Arsenal in 1876, the Chinese developed the capacity to manufacture these "electric torpedoes" on their own. under Li's direction.[2]

Because of his prominent role in Chinese diplomacy in Korea and of his strong political connections in Manchuria, Li Hongzhang found himself leading Chinese forces during the disastrous Sino-Japanese War. In fact, it was mostly the armies that he established and controlled that did the fighting, whereas other Chinese troops led by his rivals and political enemies did not come to their aid. Rampant corruption in the army further weakened China's military. For instance, one official missapropriated ammunition funds for personal use. As a result, shells ran out for the some of the warships during battle, forcing one navy commander, Deng Shichang, to resort to ramming the enemies' ship. The defeat of his modernized troops and a small naval force at the hands of the Japanese undermined his political standing, as well as the wider cause of the Self-Strengthening Movement. Li paid a personal price for China's defeat, while signing the Treaty of Shimonoseki ending the war: a Japanese assassin fired at him and wounded him below the left eye. Due to the diplomatic loss of face, Japan agreed to the immediate ceasefire Li had urged in the days before the incident.[3]

Li Hongzhang Names (details) Known in English as: Li Hongzhang or Li Hung-chang Traditional Chinese: 李鴻章 Simplified Chinese: 李鸿章 Pinyin: Lǐ Hóngzhāng Wade-Giles: Li Hung-chang Peerage : Marquis Suyi of the First Class 一等肅毅侯 Courtesy names (字): Jiànfǔ (漸甫)

Zǐfù (子黻)Pseudonyms (號):

(Yisou and Shengxin

used in his old age)Shǎoquán (少荃)

Yísǒu (儀叟)

Shěngxīn (省心)Nickname: Mr. Li the Second (李二先生)

(i.e. 2nd son of his father)Posthumous name: Wénzhōng (文忠)

(Refined and Loyal)In 1896, he attended the coronation of Emperor Nicholas II of Russia on behalf of the Qing Government and toured Europe and the United States of America,[4] where he advocated reform of the American immigration policies that had greatly restricted Chinese immigration after the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 (renewed in 1892). (He also witnessed the 1896 Royal Naval Fleet Review at Spithead.) It was during his visit to Britain in 1896 that Queen Victoria made him a Knight Grand Cross of the Royal Victorian Order.[5]

Li Hongzhang played a major role in ending the Boxer Rebellion. His early position was that the Qing Dynasty was making a mistake by supporting the Boxers against the foreign forces. He wrote to Empress Dowager Cixi:

My blood runs cold at the thought of events to come. (...) Under an enlightened sovereign these Boxers, with their ridiculous claims of supernatural powers, would most assuredly have been condemned to death long since... your Majesties... are still in the hands of traitors, regarding these Boxers as your dutiful subjects, with the result that unrest is spreading and alarm universal.

Li Hongzhang used the Siege of the International Legations (Boxer Rebellion) as a political weapon against his rivals in Beijing, since he controlled the Chinese Telegraph service, he exaggerated and lied, claiming that Chinese forces committed atrocities and murder upon the foreigners and exterminated all of them. This information was sent to the western world. He aimed to infuriate the Europeans against the Chinese forces in Beijing, and succeeded in spreading massive amounts of false information. [6]

In 1901, as his last task for the Qing Dynasty, he was the principal Chinese negotiator with the foreign powers who had captured Beijing, and, on September 7, 1901, he signed the treaty (Boxer Protocol) ending the Boxer crisis, obtaining the departure of the foreign armies at the price of huge indemnities for China. Exhausted from the negotiations, he died from liver inflammation two months later at Shenlian Temple in Beijing.[7] Guangxu created him the title Marquis Suyi of the First Class (等肅毅候). After his death, this Peerage was inherited by his grandson Li Guojie.

Legacy and assessment

Since the First Sino-Japanese War, Li Hongzhang has been a target of criticism and was portrayed in many ways as a traitor to the Chinese people, an infamous name that lives in history. In communist China this negative verdict is echoed through history textbooks and other media until today.[citation needed]

The Chinese navy had been eliminated in August 1884 at the Battle of Foochow, In July 1885, Li signed the Sino-French treaty to confirm the Treaty of Hué accepting conditions that did not reflect the decisive victory of the Chinese army in the Battle of Bang Bo in March 1885, which brought about the fall of the Jules Ferry government in France.

Li recognized talent, he hired a British officer Col Charles Gordon to lead the Ever Vicotrious Army to quell the Taipin Rebellion. For the first time in Chinese history there was a foreign military general. He hired an American educator Charles D. Tenney as tutor to teach his children western science. His decendents remain as diplomats after the Manchu Dynasty. He enjoyed western science and hired Guxtac Detering 1842-1913) and William N. Pethick. He started the custom, postal systems by appointment of Sir Robert Hart. The Chinese still use British mailboxes from Victoria era. He is also known the precipitate the invention of an American Chinese dish chopsuey.

See also

- Self-Strengthening Movement

- Military history of China (pre-1911)

- Beiyang Army

- Battle of Shanghai (1861)

Notes

This article incorporates text from Overland monthly and Out West magazine, by Bret Harte, a publication from 1886 now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from Overland monthly and Out West magazine, by Bret Harte, a publication from 1886 now in the public domain in the United States. This article incorporates text from Dietetic and hygienic gazette, Volume 13, a publication from 1897 now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from Dietetic and hygienic gazette, Volume 13, a publication from 1897 now in the public domain in the United States.

- ^ Bret Harte (1886). Overland monthly and Out West magazine. SAN FRANCISCO: NO. 120 SUTTER STREET: A. Roman & Company. p. 425. http://books.google.com/books?id=Z1U4AAAAIAAJ&pg=PA425&dq=electric+torpedoes+chinese&hl=en&ei=Ig5gTaTfJ8GAlAejx6CiDA&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=2&ved=0CCsQ6AEwATgo#v=onepage&q=electric%20torpedoes%20steel%20clad&f=false. Retrieved February 19, 2011.(Original from the University of California)

- ^ John King Fairbank (1980). Late Ch'ing, 1800–1911 Volume 11, Part 2 of The Cambridge History of China Series, Denis Crispin Twitchett. Cambridge University Press. p. 249. ISBN 0521220297. http://books.google.com/books?id=pEfWaxPhdnIC&pg=PA249&dq=electric+torpedoes+chinese&hl=en&ei=eg1gTZ3iI4SClAeurfDrCw&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=5&ved=0CDcQ6AEwBDgK#v=onepage&q=electric%20torpedoes%20chinese&f=false. Retrieved February 19, 2011.

- ^ Mutsu, Munemitsu. (1982). Kenkenroku, p. 174.

- ^ Dietetic and hygienic gazette, Volume 13. New York: The Gazette Publishing Company.. 1897. p. 472. http://books.google.com/books?id=K4xYAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA472&dq=recent+visit+of+li+hung+chang+to+our+shores&hl=en&ei=yILZTa3gEs_r0QGr0YT9Aw&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CDEQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=recent%20visit%20of%20li%20hung%20chang%20to%20our%20shores&f=false. Retrieved February 19, 2011.(Original from the University of Michigan)

- ^ Antony Best, "Race, Monarchy, and the Anglo-Japanese Alliance, 1902–1922,"Social Science Japan Journal 2006 9(2):171–186

- ^ Robert B. Edgerton (1997). Warriors of the rising sun: a history of the Japanese military. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 86. ISBN 0393040852. http://books.google.com/books?id=wkHyjjbv-yEC&pg=PA85&dq=the+siege+of+the+peking+legations+was+not+intended+to+kill+all+the+foreigners.+If+it+had+been,+nothing+would+have+been+easier+for+the+chinese+than+to+use+their+many+heavy+german+artillery+pieces+to+batter+the+barricades+and+buildings+to+rubble,+then+send+in+thousands+of+infantry&hl=en&ei=8YkGTcPnG8OblgeewNXZCQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CCMQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=li%20hung-chang%20ownership%20of%20the%20chinese%20telegraph&f=false. Retrieved November 28, 2010.

- ^ Fenby, Jonathan (2009). The Penguin History of Modern China: The Fall and Rise of a Great Power, 1850 – 2009. Penguin Books. pp. 89–90.

References

- Hummel, Arthur William, ed. Eminent Chinese of the Ch'ing Period (1644–1912). 2 vols. Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 1943.

- Liu, Kwang-ching. "The Confucian as Patriot and Pragmatist: Li Hung-Chang's Formative Years, 1823–1866." Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 30 (1970): 5–45.

- Liang Qichao,"Biography of Li Hongzhang"

- Mutsu, Munemitsu. (1982). Kenkenroku (trans. Gordon Mark Berger). Tokyo: University of Toyko Press. 10-ISBN 0860083063/13-ISBN 9780860083061; OCLC 252084846

Political offices Preceded by

Zeng GuofanActing Viceroy of Liangjiang

1865–1866Succeeded by

Zeng GuofanPreceded by

Guan WenViceroy of Huguang

1867–1870Succeeded by

Li HanzhangPreceded by

Zeng GuofanViceroy of Zhili and Minister of Beiyang (1st time)

1871—1895Succeeded by

Wang WenzhaoPreceded by

Tan ZhonglinViceroy of Liangguang

1899─1900Succeeded by

Tao MoPreceded by

Yu LuViceroy of Zhili and Minister of Beiyang (2nd time)

1900—1901Succeeded by

Yuan ShikaiCategories:- 1823 births

- 1901 deaths

- People from Hefei

- Chinese people of the Boxer Rebellion

- People of the First Sino-Japanese War

- People of the Sino-French War

- Qing Dynasty politicians

- Chinese diplomats

- Honorary Knights Grand Cross of the Royal Victorian Order

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.