- Natchez, Mississippi

-

Natchez, Mississippi — City — The historic Melrose estate, at Natchez National Historical Park, an example of the city's Antebellum era Greek Revival architecture Location of Natchez in Adams County Coordinates: 31°33′16″N 91°23′15″W / 31.55444°N 91.3875°WCoordinates: 31°33′16″N 91°23′15″W / 31.55444°N 91.3875°W Country United States State Mississippi County Adams Founded 1716 as Fort Rosalie, renamed by 1730 Incorporated Government - Mayor Area - Total 13.9 sq mi (35.9 km2) - Land 13.2 sq mi (34.2 km2) - Water 0.6 sq mi (1.7 km2) Elevation 217 ft (66 m) Population (2000) - Total 18,464 - Density 1,260.4/sq mi (486.7/km2) [1] Time zone CST (UTC-6) - Summer (DST) CDT (UTC-5) ZIP codes 39120-39122 Area code(s) 601 FIPS code 28-50440 GNIS feature ID 0691586 Website www.natchez.ms.us Natchez is the county seat[2] of Adams County, Mississippi, United States. With a total population of 18,464 (according to the 2000 census), it is the largest community and the only incorporated municipality within Adams County. Located on the Mississippi River, some 90 miles southwest of Jackson, the capital of Mississippi, and 85 miles north of Baton Rouge, Louisiana, it is the eighteenth-largest city in the state. It is named for the Natchez tribe of Native Americans who lived in the vicinity through the arrival of Europeans in the eighteenth century.

Established by French colonists in 1716, Natchez is one of the oldest and most important European settlements in the lower Mississippi River Valley, and served as the capital of the Mississippi Territory and then the state of Mississippi. It predates Jackson, which replaced Natchez as the capital in 1822, by more than a century. The strategic location of Natchez, on a bluff overlooking the Mississippi River, ensured that it would become a pivotal center of trade, commerce, and the interchange of Native American, European, and African-American cultures in the region for the first two centuries of its existence. In U. S. history, it is recognized particularly for its role in the development of the Old Southwest during the first half of the nineteenth century. It was the southern terminus of the historic Natchez Trace, which provided many pilots of flatboats and keelboats a road back to their homes in the Ohio River Valley after unloading their cargo in the city. Today Natchez serves in the same capacity for the modern Natchez Trace Parkway, which commemorates this route.

In the middle of the nineteenth century, the city became the home of a collection of extremely wealthy Southern planters, who owned vast tracts of land in the surrounding lowlands of Mississippi and Louisiana where they grew huge crops of cotton and sugar cane using slave labor. Natchez became the principal port from which these crops were exported, both upriver to Northern cities and downriver to New Orleans, where much of the cargo was exported to Europe. The planters' fortunes allowed them to build huge mansions in Natchez before 1860, many of which survive to this day and form a major part of the city's architecture and identity. Agriculture remained the primary economic sustenance for the region until well into the twentieth century.

During the twentieth century the city's economy experienced a downturn, first due to the replacement of steamboat traffic on the Mississippi River by railroads in the early 1900s, and later due to the exodus of many local industries that had provided a large number of jobs in the area. Despite its status as a popular tourist destination for much of its preserved aspects of antebellum culture, Natchez has experienced a general decline in population since 1960. It remains the principal city of the Natchez, MS–LA Micropolitan Statistical Area.

Contents

History

Pre-European settlement (to 1716)

According to archaeological excavations, the area had been continuously inhabited by various cultures of indigenous peoples since the 8th century CE[citation needed] The original site of Natchez was developed as a major village with ceremonial platform mound, built by people of the prehistoric Plaquemine culture, part of the Mississippian culture. Archaeological evidence shows they began construction of the three mounds by 1200. Additional work was done in the mid-15th century.

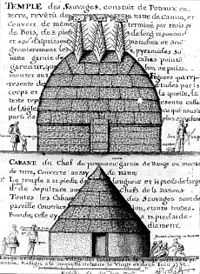

By the late 17th and early 18th century, the historical Natchez (pronounced "Nochi"), descendants of the Plaquemine culture,[3][4] occupied the site, which they used for their major ceremonial center, replacing Emerald Mound. They added to the mounds, including a residence for their chief, the "Great Sun", on Mound B, and a combined temple and charnel house for the elite on Mound C. Many early European explorers, including Hernando De Soto, La Salle and Bienville, made contact with the Natchez at this site, called the Grand Village of the Natchez. Their accounts provided descriptions of the society and village. The Natchez maintained a hierarchical society, divided into nobles and commoners, with people affiliated according to matrilineal descent. The paramount chief, the "Great Sun", owed his position to the rank of his mother.

The 128-acre (0.52 km2) site of the Grand Village of the Natchez is preserved as a National Historic Landmark and is maintained by the Mississippi Department of Archives and History. The site includes a museum with artifacts from the mounds and village, picnic pavilion, and walking trails. Nearby Emerald Mound is also a National Historic Landmark. The historic Natchez occupied it as well before moving in the late 17th century to the Natchez bluffs area.

Colonial history (1716–1783)

In 1716 the French founded Fort Rosalie to protect the trading post established in the Natchez territory in 1714. Permanent French settlements and plantations were subsequently established. The French inhabitants of the "Natchez colony" often came into conflict over land use and resources with the Natchez, who were increasingly split into pro-French and pro-English factions.

After several smaller wars, the Natchez (together with the Chickasaw and Yazoo) launched a war to eliminate the French in November 1729. It became known by the Europeans as the "Natchez War" or Natchez Massacre. The Indians destroyed the French colony at Natchez and other settlements in the area. On November 28, 1729, the Natchez Indians killed a total of 229 French colonists: 138 men, 35 women, and 56 children (the largest death toll by an Indian attack in Mississippi's history). Counterattacks by the French and their Indian allies over the next two years resulted in most of the Natchez Indians' being killed, enslaved, or forced to flee as refugees. After surrender of the leader and several hundred Natchez in 1731, the French took their prisoners to New Orleans, where they were sold as slaves and shipped as laborers to the plantations of Saint-Domingue, as ordered by the French prime minister Maurepas.[5]

Many of the refugees who escaped enslavement ultimately became part of the Creek and Cherokee nations. Descendants of the Natchez diaspora survive as the Natchez Nation, a treaty tribe and confederate of the federally recognized Muscogee (Creek) Nation, with a sovereign traditional government.[6]

Subsequently, Fort Rosalie and the surrounding town, which was renamed after the extinguished tribe, spent periods under British and then Spanish colonial rule. After defeat in the American Revolutionary War, the British ceded the territory to the United States under the terms of the Treaty of Paris (1783).

Spain was not a party to the treaty, and it was Spanish forces that had taken Natchez from the British. Although the Spanish were loosely allied with the American colonists, they were more interested in advancing their power at the expense of the British. Once the war was over, the Spanish were not inclined to give up that which they had taken by force. The Spanish retained control of Natchez for a time. A census of the Natchez district taken in 1784 counted 1,619 people, including 498 African-American slaves.

Antebellum (1783–1860)

In the late 18th century, Natchez was the starting point of the Natchez Trace overland route, based on a Native American trail, which ran from Natchez to Nashville through what is now Mississippi, Alabama, and Tennessee. Produce and goods were transported on the Mississippi River by the flatboatmen and keelboatmen, who usually sold their wares at Natchez or New Orleans, including their boats (as lumber). They made the long trek back north overland on the Natchez Trace to their homes. The boatmen were locally called "Kaintucks" because they were usually from Kentucky, although the entire Ohio River Valley was well represented among their numbers.

On October 27, 1795, the U.S. and Spanish signed the Treaty of San Lorenzo, settling their decade-long boundary dispute. All Spanish claims to Natchez were formally surrendered to the United States. More than two years passed before official orders reached the Spanish garrison there. It surrendered the fort and possession of Natchez to United States forces led by Captain Isaac Guion on March 30, 1798.

A week later, Natchez became the first capital of the new Mississippi Territory, created by the Adams administration. After it served for several years as the territorial capital, the territory built a new capital, named Washington, six miles (10 km) to the east and also in Adams County. After roughly 15 years, the legislature transferred the capital back to Natchez at the end of 1817, when the territory became a state. Later the capital was returned to Washington. As the state's population center shifted to the north and east as more settlers entered the area, the legislature voted to move the capital to the more centrally located city of Jackson in 1822.

Throughout the course of the early nineteenth century, Natchez was the center of economic activity for the young state. Its strategic location on the high bluffs on the eastern bank of the Mississippi River enabled it to develop into a bustling port. At Natchez, many local plantation owners had their cotton loaded onto steamboats at the landing known as Natchez-Under-the-Hill[7] to be transported downriver to New Orleans or, sometimes, upriver to St. Louis, Missouri or Cincinnati, Ohio. The cotton was sold and shipped to New England and European spinning mills.

The Natchez District, along with the Sea Islands of South Carolina and Georgia, pioneered cotton agriculture in the United States. Until new hybridized breeds of cotton were created in the early nineteenth century, it was unprofitable to grow cotton in the United States anywhere other than those latter two areas. Although South Carolina came to dominate the cotton plantation culture of much of the Antebellum South, it was the Natchez District that first experimented with hybridization, making the cotton boom possible.[citation needed]

The growth of the cotton industry attracted many new settlers to Mississippi, who competed with the Choctaw for their land. Despite land cessions, the settlers continued to encroach on Choctaw territory, leading to conflict. With the election of President Andrew Jackson in 1828, he pressed for Indian removal, gaining Congressional passage of an act authorizing that in 1830. Starting with the Choctaw, the government began Indian Removal in 1831 to lands west of the Mississippi River. Nearly 15,000 Choctaw left their traditional homeland over the next two years.

On May 7, 1840, an intense tornado struck Natchez. It killed 269 people, most of whom were on flatboats in the Mississippi River. The tornado killed 317 persons in all, making it the second-deadliest tornado in United States history. Today the event is called the "Great Natchez Tornado".

The terrain around Natchez on the Mississippi side of the river is hilly. The city sits on a high bluff above the Mississippi River; to reach the riverbank, one must travel down a steep road to the landing called Silver Street, which is in marked contrast to the flat "delta" lowland found across the river surrounding the city of Vidalia, Louisiana. Its early planter elite built numerous antebellum mansions and estates. Many owned plantations in Louisiana but chose to locate their homes on the higher ground in Mississippi. Prior to the American Civil War, Natchez had the most millionaires per capita of any city in the United States. It was frequented by notables such as Aaron Burr, Henry Clay, Andrew Jackson, Zachary Taylor and Jefferson Davis. Today the city boasts that it has more antebellum homes than any other city in the US, as during the War, Natchez was spared the destruction of many other Southern cities.

The Forks of the Road Market had the highest volume of slave sales in Natchez, and Natchez had the most active slave trading market in Mississippi. This also stimulated the city's wealth. The market, at the intersection of two streets, became especially important after the slave traders Isaac Franklin of Tennessee and John Armfield of Virginia purchased the land in 1823. Tens of thousands of slaves passed through the market, most originating in Virginia and the Upper South, and destined for the plantations in the Deep South. All trading at the market ceased by the summer of 1863, when Union troops occupied Natchez.[8]

Prior to 1845 and the founding of the Natchez Institute, the city's elite were the few who could pay for formal education. Although many of the parents had not had much schooling, they were anxious to provide their children with a prestigious education. Schools opened in the city as early as 1801, but many of the wealthiest families relied on private tutors or out-of-state institutions. The city founded the Natchez Institute to offer free education to the rest of the white residents of the city. Although children from a variety of economic backgrounds could obtain an education, class differences persisted among students, particularly in terms of school choice and social ties. Although it was illegal, slave children were often taught the alphabet and reading the Bible by their white age mates in private houses.[9]

American Civil War (1861–1865)

During the Civil War, Natchez remained largely undamaged. The city surrendered to Flag-Officer David G. Farragut after the fall of New Orleans in May 1862.[10] One civilian, an elderly man, was killed during the war, when in September 1863, a Union ironclad shelled the town from the river and he died of a heart attack. Union troops under Ulysses S. Grant occupied Natchez in 1863; Grant set up his temporary headquarters in the Natchez mansion Rosalie.[11]

Some Natchez residents remained defiant of the Federal authorities. In 1864, William Henry Elder, the Catholic bishop of the Diocese of Natchez, refused to obey a federal order to compel his parishioners to pray for the President of the United States. The federals arrested Elder, jailed him briefly and banished him across the river to Confederate-held Vidalia. Elder was eventually allowed to return to Natchez and resume his clerical duties there, staying until 1880, when he was elevated to archbishop of Cincinnati.

Ellen Shields's memoir reveals a Southern women's reactions to Yankee occupation of the city. Shields was a member of the local elite and her memoir points to the upheaval of Southern society during the War. Because Southern men were absent at war, many elite women had to call on their class-based femininity and their sexuality to deal with the Yankees.[12]

In 1860 there were 340 planters in the Natchez region who each owned 250 or more slaves; many were not enthusiastic Confederates. They were fairly recent arrivals to the South, opposed secession, and held social and economic ties to the North. These elite planters lacked a strong emotional attachment to the South; but, when war came, many of their sons and nephews joined the Confederate army.[13] Charles Dahlgren was among the recent migrants; from Philadelphia, he had made his fortune before the war. He did support the Confederacy and led a brigade, but was criticized for failing to defend the Gulf Coast. When the Yankees came, he moved to Georgia for the duration. He returned in 1865 but never recouped his fortune. He had to declare bankruptcy and in 1870 he gave up and moved to New York City.[14]

White Natchez became much more pro-Confederate after the war. The Lost Cause myth arose as a means for coming to terms with the South's defeat. It quickly became a definitive ideology, strengthened by its celebratory activities, speeches, clubs, and statues. The major organizations dedicated to creating and maintaining the tradition were the United Daughters of the Confederacy and United Confederate Veterans. At Natchez and other cities, although the local newspapers and veterans played a role in the maintenance of the Lost Cause, elite women particularly were important, especially in establishing memorials, such as the Civil War Monument dedicated on Memorial Day 1890, and cemeteries. The Lost Cause enabled women noncombatants to lay a claim to the central event in their redefinition of Southern history.[15]

Postwar period (1865–1900)

Natchez was able to make a rapid economic comeback in the postwar years, with the resumption of much of the commercial shipping traffic on the Mississippi River. The cash crop was still cotton, but gang labor came to be largely replaced by Sharecropping. In addition to cotton, the development of local industries such as logging added to the exports through the city's wharf. In return, Natchez saw an influx of manufactured goods from Northern markets such as Cincinnati, Pittsburgh, and St. Louis.

The city's prominent place in Mississippi River commerce during the nineteenth century was expressed by the naming of nine steamboats plying the lower river between 1823 and 1918 which were named Natchez. Many were built for and commanded by the famous Captain, Thomas P. Leathers, whom Jefferson Davis had wanted to head the Confederate defense fleet on the Mississippi River. (This appointment never was concluded.) In 1885, the Anchor Line, known for its luxury steamboats operating between St. Louis and New Orleans, launched its "brag boat", the City of Natchez. This ship survived only a year before succumbing to a fire at Cairo, Illinois, on 28 December 1886. Since 1975, an excursion steamboat at New Orleans has also borne the name Natchez.

Such river commerce sustained the city's economic growth until just after the turn of the twentieth century, when steamboat traffic began to be replaced by the railroads. The city's economy declined over the course of the century, as did that of many Mississippi river towns. Tourism has helped compensate for the decline.

After the war and during Reconstruction, the world of domestic servants in Natchez changed somewhat in response to Emancipation and freedom. After the Civil War, most domestic servants continued to be black women, and often they were single mothers. Although they were poorly paid, they found domestic work provided an important source of income for family maintenance. White employers often continued the paternalism that characterized relations between slaveholders and slaves. They often preferred black workers to white servants. White men and women who did work as domestics generally held positions such as gardener or governess, while black servants worked as cooks, maids, and laundresses.[16]

Since 1900

For a short time, the women's school Stanton College in Natchez educated daughters of the white Southern elite. It was located in Stanton Hall, built as a private mansion in 1858 and designated a National Historic Landmark in the twentieth century. During the early 20th century, the college was a site of negotiation between the planter class and the new commercial elite, as well as between traditional parents and their more modern daughters. The young women joined social clubs and literary societies that maintained relations among cousins and family friends. The coursework included classes in proper behavior and letter writing, as well as skills that might enable those suffering from genteel poverty to make a living. The girls often balked at dress codes and rules, but also replicated their parents' social values.[17]

Located on the Mississippi River, the town had long had an active nightlife. On April 23, 1940, 209 people died in a fire at the Rhythm Night Club, a black dance hall in Natchez.[18] The local paper remarked that "203 negroes bought 50 cent tickets to eternity."[18] This fire has been noted as the fourth deadliest fire in U.S. history.[19] Several blues songs pay tribute to this tragedy and mention the city of Natchez.[20]

Civil rights era and cold cases

In the early 1960s, after the admission of James Meredith as the first black to the University of Mississippi, Natchez was the center of Ku Klux Klan activity opposing integration and the civil rights movement. E. L. McDaniel, the Grand Dragon of the United Klans of America, the largest Klan organization in 1965[21], had his office in Natchez at 114 Main Street. In August of 1964, McDaniel established a klavern of the UKA in Natchez, operating under the cover name of the Adams County Civic and Betterment Association.

Despite the violence of the time, Forrest A. Johnson, Sr., a well-respected white attorney in Natchez, began to speak out and write against the Klan. From 1964 through 1965, he published an alternative newspaper called the Miss-Lou Observer, in which he weekly took on the Klan. Klansmen and their supporters conducted an economic boycott against his law practice, nearly ruining him financially.[22]

In his October 1964 report, A.E. Hopkins, an investigator for the Mississippi Sovereignty Commission, who spied on activities of residents, wrote that the FBI was in Adams County in force

"because of the alleged burning of several churches in that area as well as several bombings and the whipping of several Negroes; also, because of the murder of two Negroes from Meadville whose bodies were recovered from the Mississippi river while the murders of three civil rights workers from Philadelphia was being investigated by Federal, State and local officials."[22]

By that time, more than 100 FBI agents were in the area as part of the Philadelphia investigation and to try to keep racial violence under control. Bill Williams, an FBI agent in Natchez for two years during that time said in a 2005 interview that the "race wars in the area are 'a story never told,' that Natchez in 1964 had become the 'focal point for racial, anti-civil rights activity for the state for the next several years'."[22][23]

In 1965 two weeks after he urged the school board to accept desegregation, George Metcalfe, a NAACP official in Natchez, was seriously injured in the bombing of his car. On February 27, 1967 Wharlest Jackson Sr. was killed when a car bomb went off in his truck as he drove home from work at the Armstrong Rubber Company, where he had recently received a promotion and was working in a position previously "reserved" for whites. A Korean War veteran, married and with five children, he also had been treasurer of the NAACP. His murder was never solved and no one has been charged in the crime.[24]

In 1966, the House Un-American Activities Committee published long lists of the names of Natchez residents who were current or former members of the Klan, including over 70 employees at the International Paper plant in the city, as well as members of the Natchez police department and the Adams County Sheriff's department.[18] HUAC found that there were at least four white supremacist terrorist groups operating in Natchez during the 1960s, including the Mississippi White Caps. The MWC distributed flyers anonymously around the city, threatening "crooks and mongrelizers." The Americans for the Preservation of the White Race was founded in May 1963 by nine residents of Natchez.[18]

The Cottonmouth Moccasin Gang was founded by Claude Fuller and Natchez klansmen Ernest Avants and James Lloyd Jones. In June of 1966, they murdered Natchez resident Ben Chester White, reportedly as part of a plot to draw Dr. Martin Luther King to Natchez in order to assassinate him. The three Klansmen were arrested and charged by the state with the murder, but in each case, despite overwhelming evidence and, in Jones's case, a confession, either the charges were dismissed or the defendants were acquitted by all-white juries.[25]

James Ford Seale, arrested in 1964 as a suspect in the kidnapping and murders of Dee and Moore, had been released when the state district attorney decided not to take the case forward. Interest in the case was revived after 2000, and the FBI investigated. Seale was arrested and charged by the US Attorney. He was tried and convicted in federal court in 2007. He died in federal prison in 2011 at the age of 76.

The FBI discovered that Ben Chester White had been killed on federal land near Pretty Creek in the Homochitto National Forest of Natchez, which gave them jurisdiction. In 1999 they reopened an investigation into the case[26], and indicted Ernest Avants in 2000. He was convicted in 2003 and sentenced to life in prison. He died in prison in 2004 at age 72.[27]

In February 2011, The Injustice Files of the Investigation Discovery channel aired three TV episodes of cold case murders related to the civil rights era. The first episode was devoted to the story of Wharlest Jackson, Sr., killed in 1967, as noted above. This was part of a collaboration with the FBI, which had started an initiative in 2007 to investigate and prosecute civil rights cases.[28]

Natural disasters

In August 2005, in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, Natchez served as a refuge for coastal Mississippi and Louisiana residents, providing shelters, hotel rooms, rentals, FEMA disbursements and animal shelters. Natchez was able to keep fuel supplies open for the duration of the disaster, provide essential power to the most affected areas, receive food deliveries, and maintain law and order while assisting visitors from other areas. In the months after the hurricane, a majority of the available homes were purchased or rented, with some tenants making Natchez their permanent new home.[citation needed]

Flooding in 2011 drove the Mississippi River to crest at 61.9 ft on May 19, the highest recorded height of the river since the 1930s.

Images and memory

Historic wealthy and famous families in Natchez have used the Natchez Pilgrimage, which is an annual tour of the city's impressive antebellum mansions; to portray a nostalgic vision of its antebellum slaveholding society. Since the civil rights movement, however, this version has been increasingly challenged by blacks who have sought to portray the black experience in Natchez.[29] According to the author Paul Hendrickson, "Blacks are not a part of the Natchez Pilgrimage."[18]

A cinema verité account of the 1966 Civil Rights actions by local NAACP leaders in Natchez was depicted by the filmmaker Ed Pincus in his film Black Natchez. The film highlights the attempt to organize a black community in the Deep South in 1965 during the heyday of the Civil Rights Movement. A black leader has been car-bombed and a struggle ensues in the black community for control. A group of black men organize a chapter of the Deacons for Defense—a secret armed self-defense group. The community splits between more conservative and activist elements.[30]

By the winter of 1988 the National Park Service had established Natchez National Historical Park around Melrose. The William Johnson House, in the city was added a few years later. The tours given by the National Park Service tend to present a more complex view of the past.

The historic district has been used by Hollywood as the backdrop for feature films set in the ante-bellum period. Disney's The Adventures of Huck Finn was partially filmed here in 1993. The 1982 television movie Rascals and Robbers: The Adventures of Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn was also filmed here. The television mini-series Beulah Land was also filmed in Natchez, as well a number of individual weekly shows of the TV drama The Mississippi, starring Ralph Waite.

In 2007 a United States Courthouse was opened, after renovating a historic hall for changed use. Part of the old hall had a Jim Crow-era monument to the local men and women from Natchez and Adams County who served in World War I. The 1924 monument was the subject of several stories in the Natchez Democrat, as reporters noted it lacked representation of black Army troops who had served in the war. A story suggested the monument may be updated and the old monument retired.[31]

Geography

Natchez is located at 31°33'16" latitude, 91°23'15" longitude (31.554393, −91.387566)[32].

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 13.9 square miles (36 km2), of which 13.2 square miles (34 km2) are land and 0.6-square-mile (1.6 km2) (4.62%) is water.

Climate

Natchez has a humid subtropical climate.

Climate data for Natchez, Mississippi Month Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Year Record high °F (°C) 83

(28)85

(29)91

(33)92

(33)99

(37)102

(39)102

(39)105

(41)103

(39)98

(37)87

(31)83

(28)105

(41)Average high °F (°C) 58.3

(14.6)63.0

(17.2)71.3

(21.8)78.5

(25.8)84.3

(29.1)89.6

(32.0)91.5

(33.1)91.4

(33.0)87.3

(30.7)79.6

(26.4)69.7

(20.9)61.7

(16.5)77.2 Average low °F (°C) 37.5

(3.1)40.4

(4.7)47.9

(8.8)55.4

(13.0)62.1

(16.7)68.7

(20.4)71.7

(22.1)70.8

(21.6)66.0

(18.9)54.4

(12.4)47.5

(8.6)40.6

(4.8)55.3 Record low °F (°C) 4

(−16)8

(−13)18

(−8)28

(−2)30

(−1)49

(9)55

(13)50

(10)40

(4)27

(−3)18

(−8)5

(−15)4

(−16)Precipitation inches (mm) 6.44

(163.6)5.03

(127.8)6.74

(171.2)6.07

(154.2)5.49

(139.4)4.68

(118.9)4.03

(102.4)3.89

(98.8)3.73

(94.7)3.97

(100.8)5.58

(141.7)6.44

(163.6)60.5

(1,537)Source no. 1: The Weather Channel[33] Source no. 2: Intellicast[34] Demographics

Historical populations Census Pop. %± 1810 1,511 — 1820 2,184 44.5% 1830 2,789 27.7% 1840 3,612 29.5% 1850 4,434 22.8% 1860 6,612 49.1% 1870 9,057 37.0% 1880 7,058 −22.1% 1890 10,101 43.1% 1900 12,210 20.9% 1910 11,791 −3.4% 1920 12,608 6.9% 1930 13,422 6.5% 1940 15,296 14.0% 1950 22,740 48.7% 1960 23,791 4.6% 1970 19,704 −17.2% 1980 22,015 11.7% 1990 19,535 −11.3% 2000 18,464 −5.5% Est. 2005 16,810 −9.0% As of the census[35][1] of 2000, there were 18,464 people, 7,591 households, and 4,858 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,398.3 people per square mile (540.1/km²). There were 8,479 housing units at an average density of 642.1 per square mile (248.0/km²). The racial makeup of the city was 44.18% White, 54.49% African American, 0.11% Native American, 0.38% Asian, 0.02% Pacific Islander, 0.18% from other races, and 0.63% from two or more races. 0.70% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

There were 7,591 households out of which 29.7% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 36.6% were married couples living together, 23.5% had a female householder with no husband present, and 36.0% were non-families. 32.4% of all households were made up of individuals and 14.6% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.37 and the average family size was 3.00.

In the city the population was spread out with 26.5% under the age of 18, 8.8% from 18 to 24, 24.3% from 25 to 44, 22.4% from 45 to 64, and 18.0% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 38 years. For every 100 females there were 81.5 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 76.7 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $25,117, and the median income for a family was $29,723. Males had a median income of $31,323 versus $20,829 for females. The per capita income for the city was $16,868. 28.6% of the population and 25.1% of families were below the poverty line. 41.6% of those under the age of 18 and 23.3% of those 65 and older were living below the poverty line.

Education

Natchez is home to Alcorn State University's Natchez Campus.

Copiah-Lincoln Community College also operates a campus in Natchez.

The city of Natchez and the county of Adams operate one public school system, the Natchez-Adams School District. The district comprises eight schools. They are Susie B. West, Morgantown, Gilmer McLaurin, Joseph F Frazier, Robert Lewis Middle School, Central Alternative School, Natchez High School, and Fallin Career and Technology Center.

In Natchez, there are a number of private and parochial schools. Trinity Episcopal Day School is PK-12 school founded by the Trinity Episcopal Church. Trinity Episcopal Day School and Adams County Christian School are both members of the Mississippi Private School Association. Cathedral School is also a PK-12 school in the city. It is affiliated with the Roman Catholic Church St. Mary Basilica. Holy Family Catholic School, founded in 1890, is a PK-3 school affiliated with Holy Family Catholic Church.

Transportation

Highways

U.S. Route 61 runs north-south, parallel to the Mississippi River, linking Natchez with Port Gibson, Mississippi, Woodville, Mississippi, and Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

U.S. Route 61 runs north-south, parallel to the Mississippi River, linking Natchez with Port Gibson, Mississippi, Woodville, Mississippi, and Baton Rouge, Louisiana. U.S. Route 84 runs east-west and bridges the Mississippi, connecting it with Vidalia, Louisiana, and Brookhaven, Mississippi.

U.S. Route 84 runs east-west and bridges the Mississippi, connecting it with Vidalia, Louisiana, and Brookhaven, Mississippi. U.S. Route 65 runs north from Natchez along the west bank of the Mississippi through Ferriday and Waterproof, Louisiana.

U.S. Route 65 runs north from Natchez along the west bank of the Mississippi through Ferriday and Waterproof, Louisiana. U.S. Route 98 runs east from Natchez towards Bude and McComb, Mississippi.

U.S. Route 98 runs east from Natchez towards Bude and McComb, Mississippi. Mississippi Highway 555 runs north from the center of Natchez to where it joins Mississippi Highway 554.

Mississippi Highway 555 runs north from the center of Natchez to where it joins Mississippi Highway 554. Mississippi Highway 554 runs from the north side of the city to where it joins U.S. Highway 84 northeast of town.

Mississippi Highway 554 runs from the north side of the city to where it joins U.S. Highway 84 northeast of town.Rail

Natchez is served by rail lines, which today carry only freight.

Air

Natchez is served by the Natchez-Adams County Airport, which services general aviation. The nearest airport with commercial service is Baton Rouge Metropolitan Airport, 85 miles (137 km) to the south on US 61.

Suburbs

Natchez's surrounding communities (collectively known as the "Miss-Lou") include:

- Cloverdale, Mississippi

- Canonsburg, Mississippi

- Jonesville, Louisiana

- Morgantown, Mississippi

- Kingston, Mississippi

- Cranfield, Mississippi

- Vidalia, Louisiana

- Pine Ridge, Mississippi

- Washington, Mississippi

- Monterey, Louisiana

- Church Hill, Mississippi

- Sibley, Mississippi

- Stanton, Mississippi

- Roxie, Mississippi

Notable natives and residents

- Robert H. Adams, former United States Senator from Mississippi.[36]

- William Wirt Adams, Confederate Army officer, grew up in Natchez.[36]

- Philip Alston (counterfeiter), prominent plantation owner and early American outlaw

- Glen Ballard, a five-time Grammy Award winning songwriter/producer.

- Campbell Brown, Emmy award-winning journalist, a political anchor for CNN; grew up in Natchez and attended both Trinity Episcopal and Cathedral High School.

- John J. Chanche, First Bishop of Natchez, is buried on the grounds of St. Mary Basilica, Natchez.

- Olu Dara, musician & father of rapper Nas.

- Varina Howell Davis, first lady of the Confederate States of America, was born, raised, and married in Natchez.

- Je'Kel Foster, basketball player.

- Mickey Gilley, a country music singer, was born in Natchez.

- Cedric Griffin, Minnesota Vikings cornerback, was born in Natchez but raised in San Antonio, Texas.

- Hugh Green, All-American defensive end at the University of Pittsburgh and two-time Pro Bowler.

- Troyce Guice, Natchez restaurant owner, was twice a candidate for the United State Senate from Louisiana.

- Von Hutchins, NFL football player for the Atlanta Falcons.

- Greg Iles, born in Natchez and a best-selling author of many novels set in the city.

- William Johnson, "The Barber of Natchez", freed slave and prominent businessman.[37]

- Nook Logan, former Major League Baseball player for the Washington Nationals.

- John R. Lynch, The first African-American Speaker of the House in Mississippi and one of the earliest African-American members of Congress

- Lynda Lee Mead, Miss Mississippi in 1959 and Miss America in 1960. A Natchez city street, Lynda Lee Drive, is named in her honor.

- Anne Moody, civil rights activist and author of Coming of Age in Mississippi, attended Natchez Junior College.

- Alexander O'Neal, R&B singer.

- General John Anthony Quitman – Mexican War hero, plantation owner, governor of Mississippi, owner of Monmouth Plantation.

- Pierre Adolphe Rost, a member of the Mississippi Senate and commissioner to Europe for the Confederate States, immigrated to Natchez from France.

- Billy Shaw, Pro Football Hall of Fame member, was born in Natchez.

- Chris Shivers, two-time PBR world champion bull rider, was born in Natchez.

- Hound Dog Taylor, a blues singer and slide guitar player.

- Don José Vidal, Spanish Governor of the Natchez District, is buried in the Natchez City Cemetery.[38]

- Joanna Fox Waddill, American Civil War nurse known as the "Florence Nightingale of the Confederacy."

- Samuel Washington Weis (1870–1956), an American painter

- Les Whitt, director of the municipal zoo in Alexandria, Louisiana, and a musician who sometimes played with B.B. King.

- Novelist Richard Wright, author of Black Boy and Native Son, was born in Rucker Plantation in Roxie, Mississippi, twenty-two miles east of Natchez.

See also

- Alcorn State University

- Arlington (Natchez, Mississippi)

- Auburn (Natchez, Mississippi)

- Commercial Bank and Banker's House

- Dunleith

- Great Natchez Tornado

- House on Ellicott's Hill

- Longwood (Natchez, Mississippi)

- Melrose (Natchez, Mississippi)

- Monmouth (Natchez, Mississippi)

- Natchez National Cemetery

- Natchez National Historical Park

- Natchez On-Top-of-the-Hill Historic District

- Stanton Hall

- United States Courthouse (Natchez, Mississippi)

Notes

- ^ a b 2000 census data for Natchez

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. http://www.naco.org/Counties/Pages/FindACounty.aspx. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- ^ Douglas C. Wells; Richard A. Weinstein (2007). "Extra regional contact and culktural interaction at the Coles Creek - Plaquemine transition : Recent data from the Lake Providence Mounds, East Carroll Parish, Louisiana". In Rees, Mark A.; Livingood, Patrick C.. Plaquemine Archaeology. University of Alabama Press. pp. 38-55.

- ^ "Louisiana Prehistory : Plaquemine Mississippian". http://www.crt.state.la.us/archaeology/virtualbooks/LAPREHIS/plaqu.htm. Retrieved 2011-10-24.

- ^ Ginny Walker English, "Natchez Massacre 1729", State Coordinator, Mississippi American Local History Network, 2000–2001, accessed 3 May 2009

- ^ Natchez Nation official web site[dead link]

- ^ [1]

- ^ Jim Barnett and H. Clark Burkett, "The Forks of the Road Slave Market at Natchez," Journal of Mississippi History, Sept 2001, Vol. 63 Issue 3, pp 168–187

- ^ Julia Huston Nguyen, "The Value of Learning: Education and Class in Antebellum Natchez," Journal of Mississippi History, Sept 1999, Vol. 61 Issue 3, pp 237–263,

- ^ A. T. Mahan (1898). The Navy in the Civil War. London: Sampson Low, Marston, and Company. (available at gutenberg.org)

- ^ "A Brief History of Rosalie Mansion", Official Website

- ^ Joyce L.. Broussard, "Occupied Natchez, Elite Women, and the Feminization of the Civil War," Journal of Mississippi History, Summer 2008, Vol. 70 Issue 2, pp 179–208

- ^ William K. Scarborough, "Not Quite Southern: The Precarious Allegiance of the Natchez Nabobs in the Sectional Crisis," Prologue, Winter 2004, Vol. 36 Issue 4, pp 20–29

- ^ Herschel Gower, Charles Dahlgren of Natchez: The Civil War and Dynastic Decline (2003)

- ^ Melody Kubassek, "Ask Us Not to Forget: The Lost Cause in Natchez, Mississippi," Southern Studies, 1992, Vol. 3 Issue 3, pp 155–170

- ^ Julia Huston Nguyen, "Laying the Foundations: Domestic Service in Natchez, 1862–1877," Journal of Mississippi History, March 2001, Vol. 63 Issue 1, pp 34–60

- ^ Cita Cook, "The Modernized Elitism of Young Southern Ladies at Early Twentieth-Century Stanton College," Journal of Mississippi History, Sept 2000, Vol. 62 Issue 3, pp 199–223

- ^ a b c d e Hendrickson, Paul (2003). Sons of Mississippi. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 0375404619.

- ^ National Fire Protection Association.

- ^ Luigi Monge. "Death by Fire: African American Music on the Natchez Rhythm Club Fire". in Robert Springer (1 June 2007). Nobody Knows Where the Blues Come from: Lyrics and History. Univ. Press of Mississippi. pp. 76ff. ISBN 978-1-934110-29-4. http://books.google.com/books?id=sgwBhIm3sC4C&pg=PR7. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ "Emergence of the UKA". Anti-Defamation League. 2007. http://www.adl.org/issue_combating_hate/uka/rise.asp. Retrieved 2007-09-18.

- ^ a b c Donna Ladd, "Evolution of A Man: Lifting The Hood In South Mississippi", Jackson Free Press, 26 October 2005, accessed 15 October 2011

- ^ Note: Hopkins was referring to the murders of the 19-year-old black men Henry Hezekiah Dee and Charles Eddie Moore.

- ^ Donna Ladd, "Daddy, Get Up: This Son of Natchez Wants Justice, Too", Jackson Free Press, 26 October 2005, accessed 16 October 2011

- ^ Newton, Michael (2010). The Ku Klux Klan in Mississippi: a History. McFarland and Company. p. 171. ISBN 9780786446537. (available on Google books)

- ^ Kevin Cooper, "White was an unlikely Klan target", Natchez Democrat, 5 December 1999, accessed 16 October 2011

- ^ "Ben Chester White", Civil Rights and Restorative Justice, Northeastern University, 2011, accessed 16 October 2011

- ^ FELICIA R. LEE, "TV Series Tries to Revive Civil Rights Cold Cases", New York Times, 15 February 2011, accessed 16 October 2011

- ^ Jack E Davis, "A Struggle for Public History: Black and White Claims to Natchez's Past," Public Historian, Jan 2000, Vol. 22 Issue 1, pp 45–63

- ^ See "Ed Pincus’s Black Natchez (1967)" F.I.L.M. 2010, Hamilton University Film Series

- ^ "Names to be added to war plaques", Natchez Democrat, 4 November 2010

- ^ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. http://www.census.gov/geo/www/gazetteer/gazette.html. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- ^ "Monthly Averages for Natchez, MS". http://www.weather.com/outlook/recreation/outdoors/wxclimatology/monthly/39120. Retrieved 8 April 2010.

- ^ "Intellicast – Natchez Historic Weather Averages". http://www.intellicast.com/Local/History.aspx?location=USMS0255. Retrieved 8 April 2010.

- ^ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. http://factfinder.census.gov. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ^ a b Who Was Who in America, Historical Volume, 1607–1896. Chicago: Marquis Who's Who. 1963. ISBN 1-299-64851-7.

- ^ National Park Service. The Barber of Natchez: The Life of William Johnson

- ^ Maude K. Barton (1915-14-03). "Historic Cemeteries of Natchez". Natchez Democrat. http://www.natchezcitycemetery.com/custom/webpage.cfm?content=content&id=4. Retrieved 2009-11-03.

References

- Boler, Jaime Elizabeth. City under Siege: Resistance and Power in Natchez, Mississippi, 1719–1857, PhD. U. of Southern Mississippi, Dissertation Abstracts International 2006 67(3): 1061-A. DA3209667, 393p.

- Brazy, Martha Jane. An American Planter: Stephen Duncan of Antebellum Natchez and New York, Louisiana State U. Press, 2006. 232 pp.

- Broussard, Joyce L. "Occupied Natchez, Elite Women, and the Feminization of the Civil War," Journal of Mississippi History, 2008 70(2): 179–207,

- Cox, James L. The Mississippi Almanac. New York: Computer Search & Research, 2001. ISBN 0-9643545-2-7.

- Davis, Jack E. Race Against Time: Culture and Separation in Natchez Since 1930, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2001.

- Davis, Ronald L. F. Good and Faithful Labor: from Slavery to Sharecropping in the Natchez District 1860-1890, Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1982.

- Gandy, Thomas H. and Evelyn. The Mississippi Steamboat Era in Historic Photographs: Natchez to New Orleans, 1870–1920. New York: Dover Publications, 1987.

- Gower, Herschel. Charles Dahlgren of Natchez: The Civil War and Dynastic Decline Brassey's, 2002. 293 pp.

- Inglis, G. Douglas. "Searching for Free People of Color in Colonial Natchez," Southern Quarterly 2006 43(2): 97–112

- James, Dorris Clayton. Ante-Bellum Natchez (1968), the standard scholarly study

- Libby, David J. Slavery and Frontier Mississippi, 1720–1835, U. Press of Mississippi, 2004. 163 pp. focus on Natchez

- Nguyen, Julia Huston. "Useful and Ornamental: Female Education in Antebellum Natchez," Journal of Mississippi History 2005 67(4): 291–309

- Nolan, Charles E. St. Mary's of Natchez: The History of a Southern Catholic Congregation, 1716–1988 (2 vol 1992)

- Way, Frederick. Way's Packet Dictionary, 1848–1994: Passenger Steamboats of the Mississippi River System Since the Advent of Photography in Mid-Continent America. 2nd ed. Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 1994.

- Wayne, Michael. The Reshaping of Plantation Society: The Natchez District, 1860–1880 (1983).

External links

- Official Travel & Tourism Website

- Official City Website

- City's Daily Newspaper

- History of Natchez's Jewish community (from the Institute of Southern Jewish Life)

- Interactive Map of Natchez Oil Wells Mississippi Oil Journal

- Natchez Library Institute Accounts (MUM00328) at the University of Mississippi.

- Natchez City Cemetery

- History of the Catholic Community of Natchez

Municipalities and communities of Adams County, Mississippi County seat: Natchez Cities Natchez

Unincorporated

communitiesMorgantown | Pine Ridge | Sibley | Stanton | Washington

>

Categories:- Populated places established in 1716

- Populated places in Adams County, Mississippi

- Archaeological sites in Mississippi

- Cities in Mississippi

- Mississippi populated places on the Mississippi River

- Former United States state capitals

- County seats in Mississippi

- Populated places in Mississippi with African American majority populations

- Natchez micropolitan area

- Natchez, Mississippi

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.