- Trams in Melbourne

-

Melbourne tramway network

D1.3508 in Bank of Melbourne wrap livery outside Melbourne Town Hall, Swanston Street, 2011. Operation Locale Melbourne, Victoria, Australia Cable tram era: 1885–1940 Operator(s) Melbourne Tramway and Omnibus Company (1885–1916)

Melbourne Tramways Board (1916-1919)

Melbourne and Metropolitan Tramways Board (MMTB)

(1919–1940)Track gauge 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) Propulsion system(s) Cables Electric tram era: since 1906 Owner(s) Various owners (1906–1959)

MMTB (1920–1983)

Metropolitan Transit Authority (1983-1989)

Public Transport Corporation (1989-1999)

VicTrack (since 1999)Operator(s) Various operators (1906–1959)

MMTB (1920–1983)

Metropolitan Transit Authority (1983-1989)

Public Transport Corporation (1989-1999)

M>Tram (1999–2004)

Transdev TSL (Yarra Trams)

(1999–2009)

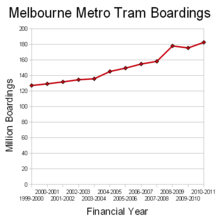

KDR Melbourne (Yarra Trams) (since 2009)Track gauge 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) Propulsion system(s) Electricity Electrification 600 V DC Track length (total) 250 km (155.3 mi) Passengers (2010-2011) 182.7 million  4.1%

4.1%Website Yarra Trams The Melbourne tramway network is a major form of public transport in Melbourne, the capital city of the state of Victoria, Australia. As of June 2011[update], the network consisted of 250 km (155.3 mi) of track, 487 trams, 28 routes, and 1,773 tram stops.[1] It was therefore the largest urban tramway network in the world,[2] ahead of the networks in St. Petersburg (240 km (150 mi)), Berlin (190 km (120 mi)), Moscow (181 km (112 mi)) and Vienna (172 km (107 mi)).[3]

Trams are a distinctive part of Melbourne's character and feature in tourism and travel advertising. In terms of overall boardings, they are the second most used form of public transport in Melbourne after the commuter railway network, with a total of 182.7 million passenger trips - a 4.1% year on year patronage growth - in the 2010-2011 year.[4]

Melbourne's tramway network is based on standard gauge tracks and powered by overhead wires at 600 volts DC.[5]

The network is operated under contract, the current private operator being KDR Melbourne, trading as Yarra Trams. Ticketing, public information and patronage promotion are undertaken by Melbourne's multi-modal service provider, Metlink. Metcard and myki multi-modal integrated ticketing systems currently operate over the tram network.[6]

At some Melbourne intersections, motor vehicles are required to perform a hook turn, a manoeuvre designed to give trams priority.[7] To further improve tram speeds on congested Melbourne streets, trams also have priority in road usage, with specially fitted traffic lights and exclusive lanes being provided either at all times or in peak times, as well as other measures.[8][9]

Contents

History

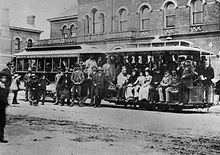

Cable trams

Melbourne's cable tram system has its origins in the Melbourne Tramway & Omnibus Company (MTOC), started by Francis Boardman Clapp in 1877, with a view to operate a Melbourne tram system. After some initial resistance, he successfully lobbied the government who passed the Melbourne Tramway & Omnibus Company Act 1883 on 10 October 1883, granting the company the right to operate a cable tram system in Melbourne. Although some lines were originally intended to be horse trams, and the MTOC did operated three horse tram lines on the edges of the system, the core of the system was built as cable trams.[10][11]

The Act established the Melbourne Tramways Trust (MTT), which was made up of the 12 municipalities that the MTOC system would serve. The MTT was responsible for the construction of tracks and engine house, while the MTOC built the depots, offices and arranged for the delivery or construction of the rolling stock. The MTT granted a lease to operate the system until 1 July 1916 to the MTOC, with the MTOC paying 4.5% interest on the debts incurred by the MTT in building the system.[10][11]

The first cable tram line opened on 11 November 1885, running from Bourke Street to Hawthorn Bridge, along Spencer Street, Flinders Street, Wellington Parade and Bridge Road, with the last line opening on 27 October 1891. At its height the cable system had 75 kilometres (47 mi) of double track, 1200 grips and trailers and 17 routes covering (103.2 route km or 64.12 route miles).[11][12]

On 18 February 1890, the Northcote tramway was opened by the Clifton Hill to Northcote & Preston Tramway Company. This was Melbourne's only non-MTOC cable tram, built by local land speculators and was operated as an independent line, feeding the Clifton Hill line.[13]

When the lease expired on 1 July 1916, all the assets of the MTT and MTOC cable network were taken over by the Melbourne Tramways Board (MTB).[10] The Melbourne and Metropolitan Tramways Board (MMTB) was formed on 1 November 1919, taking over the MTB cable tram network, with the Northcote tramway and the tramway trusts transferred to the MMTB on 20 February 1920.[14][15]

From 1924 the cable tram lines were progressively converted to electric trams, or abandoned in favour of buses, with the last Melbourne cable tram operating on 26 October 1940.[16][14]

Electric trams

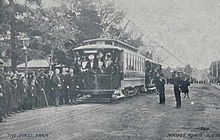

The first electric tram in Melbourne was built in 1889 by the Box Hill and Doncaster Tramway Company Limited - an enterprise formed by a group of land developers - and ran from Box Hill railway station along what is now Station Street and Tram Road to Doncaster, using equipment left over from the Centennial International Exhibition of 1888 at the Royal Exhibition Building. The venture was marred with disputes and operational problems, and ultimately failed, with the service ceasing in 1896.[17]

After this failed experiment, electric trams returned on 5 May 1906, with the opening of the Victorian Railways' 'Electric Street Railway' from St Kilda to Brighton, and was followed on 11 October 1906 with the opening of the North Melbourne Electric Tramway and Lighting Company system, which opened two lines from the cable tram terminus at Flemington Bridge to Essendon and Saltwater River (now Maribyrnong River).[18]

The Victorian Railways line came about when Sir Thomas Bent became Premier of the State. A corrupt politician and leading land boomer, he stood to benefit from construction of the line, through the increased value of his large land holdings in the area, and pushed through the legislation to enable to building of the line by the VR in 1904.[19]

The VR tram was called a "Street Railway" and was built using the Victorian railway 1,600 mm (5 ft 3 in) broad gauge instead of the cable tramway standard gauge of 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in), and connected it with the St Kilda railway station, to allow trams to be moved along the St Kilda railway line for servicing at Jolimont Yard.[20] The line was opened in two stages, from St Kilda railway station to Middle Brighton on 5 May 1906 and to Brighton Beach terminus on 22 December 1906.[18]

A fire at the Elwood tram depot on 7 March 1907 destroyed the depot and all the trams. Services resumed on 17 March 1907 using four C-class trams and three D-class trams from Sydney, which were altered to run on VR trucks salvaged from the fire. These trams sufficed until Newport Railway Workshops built 14 new trams. The St Kilda to Brighton Beach Electric Street Railway closed on 28 February 1959 and was replaced by buses.[20][21]

VR opened a second, standard gauge, electric tramway from Sandringham railway station to Black Rock on 10 March 1919, it was extended to Beaumaris on 2 September 1926. The service was withdrawn on 5 November 1956 and replaced with buses.[22][23]

Due to demand for better public transport in Melbourne's inner suburbs of Prahran and Malvern the Prahran & Malvern Tramways Trust Act 1907 was enacted. Councillor Alex Cameron of Malvern, who led the push for a municipal tramway service, was elected chairman of the trust by both Malvern & Prahran councils. Construction began on its first tram line in 1909 with the first passenger service commencing in 30 May 1910. Using overhead wires to feed electricity to the trams, this network continued to expand so greatly & profitably that when the MMTB was established in July 1919 Alex Cameron was appointed its full-time chairman.[24][25]

Network under MMTB

In the "golden era" of the 1920s and 1930s, loadings were heavy, a tram conductor earned more than a schoolteacher or a policeman, and the rolling stock was well maintained.

Alex Cameron, Chairman of the MMTB was in charge of a tramway network that had both cable and electric traction and had been constructed by different bodies without any uniform system. Under Cameron's guidance the Tramways Board was to bring these under a single control, extend the electric lines, and convert the existing cable-system to electric traction.[26][25] To solve operational and maintenance problem the MMTB introduced in 1923 the iconic W-class tram and phased out the other models.[27]

In March 1923 Alex Cameron went overseas to investigate traffic problems. He returned next year confirmed in his long-held opinions that electric trams were superior to buses and that overhead wires were preferable to the underground conduit (cable) system. Alex Cameron remained chairman there until 1935. He died a few years later in 1940, the same year the last of the cable tram services in Melbourne ended.[25]

The MMTB generated further patronage by developing the enormous Wattle Park in the 1920's and 1930's, it had inherited Wattle Park from the Hawthorn Tramways Trust with the HTTs takeover by the MMTB.[28]

After World War II other Australian cities began to replace their trams with buses. However, in Melbourne, the Bourke Street buses were replaced by trams in 1955,and new lines opened to East Preston and East Brunswick.

Melbourne's tram usage peaked at 260 million trips in 1949, before dropping sharply to 200 million the following year in 1950.[29] However usage defied the trend and bounced back in 1951, but began a gradual decline in usage which would continue until 1970.[29] During the same period bus use also went into decline and buses have never proved as popular with passengers as trams at any time in Melbourne's history.

By the 1970s Melbourne was the only Australian city with a major tram network. Melbourne resisted the trend to shut down the network partly because the city's wide streets and geometric street pattern made trams more practicable than in many other cities, partly because of resistance from the unions, and partly because the Chairman of the MMTB, Sir Robert Risson, successfully argued that the cost of ripping up the concrete-embedded tram tracks would be prohibitive. Also, the infrastructure and vehicles were relatively new, having only replaced Cable Tram equipment in the 1920s-1940s. This destroyed the argument used by many other cities, which was that renewal of the tram system would cost more than replacing it with buses.

Rebirth

By the mid 1970s, as other cities became increasingly choked in traffic and air pollution, Melbourne was convinced that its decision to retain its trams was the correct one, even though patronage had been declining since the 1950s in the face of increasing use of cars and the shift to the outer suburbs, beyond the tram network's limits.

The first tram line extension in over twenty years took place in 1978, along Burwood Highway. The W-class trams were gradually replaced by the new Z-class trams in the 1970s, and by the A-class trams and the larger, articulated B-class trams in the 1980s.

In 1980, the controversial Lonie Report recommended the closure of seven tram lines. Public protests and union action resulted these closures not being carried out.[30]

By 1990, the tram network was making losses of many millions of dollars, which was borne by the Victorian state government. In 1990, the Labor government of Premier John Cain tried to introduce economies in the running of the system, which provoked a long and crippling strike by the powerful tramways union in January 1990. Use of the network slumped to its lowest point - below 100 million trips for the first and only time since trams were in operation. In 1992, the Liberals came to power under Premier Jeff Kennett and pledged to corporatise Melbourne's public transport network. However, the policy shifted to supporting the privatisation of the tram system in the wake of a series of public transport strikes. The government abolished tram conductors and replaced them with ticketing machines, shortly before the system was privatised. This move was highly unpopular with the travelling public and led to the loss of millions of dollars in revenue through fare evasion.[31] However, use of the system began a gradual increase. The increase in patronage, beginning in the mid 1990s, accompanied the revival of the inner urban population.

Privatisation

On 1 July 1997, in preparation for privatisation of the Public Transport Corporation, Melbourne's tram network was split into two businesses – Met Tram 1 (later renamed Swanston Trams) and Met Tram 2 (later renamed Yarra Trams).[32] A new statutory authority was created within the Victorian Government in 1997, VicTrack, to hold the ownership of land and assets relating to Victoria's tram and rail systems.[33] In addition, a statutory office was established - the Director of Public Transport - to procure rail and tram services and to enter into and manage contracts with transport operators.[34]

After a tendering process the businesses were awarded as 12-year franchises, with Swanston Trams won by National Express Group PLC, a European mass passenger transport company, and the Yarra Trams business by MetroLink Victoria Pty Ltd, joint venture between French company Transdev and Australian company Transfield Services.[35][36] Following a transitional period, the right to operate the two tram businesses was officially transferred from the government to the private sector under franchise agreements on 29 August 1999.[35]

National Express renamed Swanston Trams as M>Tram, similarly along with its M>Train suburban train business, on 1 October 2001.[35] After several years of failing to make a profit, more than a year of negotiations over revised financing arrangements with the government, and grave concern over its future viability, National Express Group announced on 16 December 2002, its decision to walk away from all of their Victorian contracts and hand control back to the state government, with funding for its operations to stop on 23 December 2002.[37][38] The government ran M>Tram until negotiations were completed with Yarra Trams for it to take-over responsibility of the whole tram network from 18 April 2004.[35][32]

On 25 June 2009, it was announced that Keolis/Downer EDI will be the operator of the Melbourne tram network from 30 November 2009. Their contract is for 8 years with an option of a further 7 years.[39]

Recent

As a part of the privatisation process, franchise contracts between the state government and both private operators included obligations to extend and modernise the Melbourne tram network. This included acquiring new tram rolling stock, in addition the existing tram fleet was refurbished.[40][41]

Swanston Trams (M>Tram) introduced 59 new Combino (D-class) low-floor trams by Siemens AG, at a cost of A$175 million, and invested approximately A$8 million in refurbishing their fleet, while the Yarra Trams consortium introduced 36 Citadis (C-class) low-floor trams from Alstom, at a cost of A$100 million, and invested A$5.3 million refurbishing their fleet.[41][42][43]

In 2003 the marketing and umbrella brand Metlink was introduced to co-ordinate the promotion of Melbourne's public transport and the communications from the separate privatised companies. Metlink's role is to provide timetables, passenger information about connecting services provided by several operators, fares and ticketing information and introduce uniform signage across the Melbourne public transport system.[44][45]

Since privatisation extensions have been made to the tram system, with the $28 million extension of the 109 to Box Hill opening on 2 May 2003,[46] a $7.5 million extension along Docklands Drive in Docklands opened on 4 January 2005,[47] and a $42.6 million extension of the 75 to Vermont South opening on 23 July 2005.[48]

It was announced on 29 September 2010 that Bombardier Transportation had won a $303 million contract to supply and maintain 50 new E class trams, with an option for a further 100 to be ordered. They will be built at Bombardier's Dandenong factory, with the propulsion systems and bogies coming from Bombardier’s factories in Mannheim and Siegen, Germany, respectively. The trams will be 33 meters long and have a capacity of 210 passengers and are due to be in service in 2012.[49][50]

As of June 2011 Yarra Trams and the Department of Transport have introduced 330 level boarding platform stops to the network since 1999.[51]

Routes

Melbourne's tram system comprises 27 regular revenue routes and the free city circle service,[1] although there are a number of irregular routes and special services. From 28 August 2011 irregular route numbers started changing, aiming to simplify the numbering system, avoiding passenger confusion. Under theses changes route numbers suffixed with an "a" run an altered service, and route numbers suffixed with a "d" terminate at depots.[52]

Fleet

The Melbourne tram fleet currently comprises 487 trams.[1]

All the rolling stock is leased to Yarra Trams, with the W, Z, A and B class trams owned by the Victorian Government, and the C class and D classes are subject to lease purchase agreements, while the C2 class trams leased from Mulhouse, France.[53][54]

W-class trams

Main article: W-class Melbourne tram- 752 trams built in total 1923-1956, in service 1923–present

- ~230 total currently, ~200 in storage, 26 in revenue service, 12 on city circle

W-class trams were introduced to Melbourne in 1923 as a new standard design. They had a dual-bogie layout with a distinctive 'drop centre' section, allowing the centrally placed doors to be lower to the ground. They are a simple rugged design, with a substantially timber frame, supplanted by a steel under-frame, characterised by fine craftsmanship. The W-class was the mainstay of Melbourne's tramways system for 60 years. A total of 752 trams of 12 variants were built, the last in 1956.[55][27][56]

It was not until the 1980s that the W-class started to be replaced in large numbers, and by 1990 their status as an icon for the city was recognised, leading to a listing by the National Trust. Public outrage over their sale for tourist use overseas led to an embargo on further export out of the country in 1993, though recently some have been given or loaned to various Museums. Approximately 200 of the W-class trams retired since then remain stored, and the future use of these trams is unknown.[56][57]

W-class trams have been sent overseas, five went to Seattle between 1978 and 1993, where they operated on Seattle's George Benson Waterfront Streetcar Line, starting in 1982 but suspended in 2005. Another nine are now part of the downtown Memphis tourist service, while several other US cities have one or two.[55]

As of 2010, there are about 230 W-class trams, about 200 are in storage, 12 run on the City Circle - the oldest W-class tram in service runs on the City Circle - and 26 are used in revenue service.[58] In January 2010, it was announced by the new transport minister that the 26 W-class trams running the two inner city routes, would be phased out by 2012, prompting a new campaign from the National Trust of Australia.[59][60] In 2010 it was proposed to better utilise the unused W-class trams by refurbishing and leasing them as "roving ambassadors" to other cities, generating revenue which could then be invested back into the public transport system.[61]

Z-class trams

Main article: Z-class Melbourne tram- Z1 - 100 built, made in Australia, 30 currently in service

- Z2 - 15 built, made in Australia, 3 currently in service

- Z3 - 115 built, made in Australia, 114 currently in service

The development of new rolling stock to replace the W-class finally began in the early 1970's with a modern design, based on the Gothenburg, Sweden M28 design.[62]

The Z-class trams, built by Comeng, were introduced from 1975, starting with the Z1 class. Built from 1975 to 1979 100 trams were built, they had conductors consols that passengers would have to queue for, and only two doors, these two features hampered loading, and proved unpopular.[62] Most of Z1's were withdrawn following the introduction of the C and D class trams, leaving 30 in service. Those withdrawn were usually sold at auction, with some being donated to tram museums.[63]

In 1978 and 1979, fifteen Z2-class trams, having little difference from the Z1 class were built.[62] As with the Z1 class, many Z2-class trams have been withdrawn from service, with three remaining in service.[64]

From 1979 to 1984, Z3-class trams were introduced, being a significant improvement on the Z1- and Z2-class trams. They had an additional door each side, removed the conductors console and much smoother acceleration and braking.[62] 115 were built, 114 of which are in service (Z3.149 was destroyed in a fire). All are re-liveried in either Yarra Trams or all-over advertising livery.[65]

A-class trams

Main article: A-class Melbourne tram- A1-class - 28 built, made in Australia, all still in service

- A2-class - 42 built, made in Australia, all still in service

The A-class trams were built between 1984 and 1986 by Comeng. They were built as two runs, the A1's - introduced into service between 1984 and 1885 - and A2's - introduced into service between 1985 and 1886 - they were both very similar, the major difference being the brakes and that A1's were built with trolley poles, while A2's were built with pantographs.[66] All 70 that were built are still in service today.[67][68]

-

An A1-class tram at Federation Square, Flinders Street

B-class trams

Main article: B-class Melbourne tram- B1 - 2 built, made in Australia, both still in service

- B2 - 130 built, made in Australia, all currently in service, air conditioned

The B-class trams (also known as light rail vehicles) were first introduced to Melbourne in 1984 with the first prototype B1-class trams, the second being built in 1985, both remain in service today.[69] The B-class trams used the same traction equipment as the Z3 and A class trams, and were built for the light rail lines. They were originally built with movable steps to allow railway platform and street level boarding, but this concept was later abandoned, with low floor platform built at the converted light rail stations.[70]

B2-class trams entered service from 1988–1994, by Comeng, and later ABB Transportation, with 130 built, all of which remain in service today. The B2-class was the first Melbourne tram fitted with air-conditioning.[70][71]

All of the B-class trams, are either in Yarra Trams livery or covered with all over advertising.[71]

-

A B2-class tram in Flinders Street

C-class trams (Citadis)

Main articles: C-class Melbourne tram and C2-class Melbourne tram- C1 - 36 in service, made in France

- C2 - 5 in service, leased from Mulhouse, France ("Bumblebees")

Following the privatisation of Melbourne's tram system the private operators acquired new trams to replace the older Z-class trams. In 2001 Yarra Trams introduced the Citadis or C-class, manufactured in France by Alstom. They are three section articulated vehicles, with 36 in service.[72][42]

Five low floor C2-class trams were introduced in 2008 after being leased from Mulhouse in France. They have been dubbed 'Bumblebees' due to their distinctive yellow colour, and exclusively run on route 96. It was announced in November 2010 that the State Government was in negotiations to purchase the 5 C2 trams.[73][54]

The C class trams are owned by Allco entity and are subject to a lease purchase agreement, while the C2 class trams leased from Société Générale entity.[53]

D-class trams (Combino)

- D1 - 38 in service, made in Germany

- D2 - 21 in service, made in Germany

Following the privatisation of Melbourne's tram system the private operators acquired new trams to replace the older Z-class trams. The German made Siemens Combino trams were introduced by the now defunct M>Tram. M>Tram operations were transferred to Yarra Trams in 2004 following negotiations with the State Government after National Express walked away from its contract to operate M>Tram in 2002.[43][32]

The Combino is a three-section (D1-class) or five-section (D2-class) articulated vehicle. Currently 38 D1-type and 21 D2-type vehicles are in service.[74][75]

The D1 class and D2 class trams are owned by CBA entity and are subject to a lease purchase agreement.[53]

Popular culture

The "flying tram" featured in the Commonwealth Games Opening Ceremony, sitting on a Melbourne street map.

Melbourne's trams - especially the W class - are an icon of Melbourne and important part of its history and character. Trams have been featured across several media, and in tourism advertising since World War II.[76][77]

Trams are a heavily featured in the movie Malcolm, one scene of the controversial film Alvin Purple, and feature in the video clips for, the Beastie Boys "The Rat Cage" and AC/DC's "It's a Long Way to the Top".[76][78] Among songs written about Melbourne's trams are, "Toorak Tram" by Bernard Bolan,[79] "Taking the tram to Carnegie" by Oscar[80] and many songs including "Man on a Tram" and "Northcote (So Hungover)" by The Bedroom Philosopher, from the ARIA-nominated album, Songs From The 86 Tram.[81]

For the Melbourne 2006 Commonwealth Games a Z class tram was decorated as a Karachi bus by a team of Pakistani decorators. Dubbed the Karachi tram, it operated on the City Circle tourist route during the Commonwealth Games. [82] While the centrepiece of the Opening Ceremony was a flying W class tram, specially built for the event, from original W class plans and photos.[83]

On 26 October 2011, a Z class tram, specially liveried as a Royal Tram was used to convey Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh from Federation Square to Government House, along St Kilda Road during their visit to Melbourne. The Royal Tram is intended to be in regular service for one year following the event.[84][85]

Legislation and governance

Transport Integration Act

Main article: Transport Integration ActThe prime rail related statute in Victoria is the Transport Integration Act, the Act was enacted to provide an overarching legislation for Victoria's transport system. It requires state agencies charged with providing transport services to work together towards an integrated transport system, and requires state planning bodies to consult the Act when making decisions that will affect the transport system.[86][87]

The Act establishes Transport Safety Victoria (TSV) as Victoria's safety regulator for bus, maritime and rail transport. The Act also establishes the independent office of the Director, Transport Safety, though who the regulatory function is carried out with the support of TSV.[88]

Another important piece of legislation is the Rail Management Act 1996, whose purpose is to establish a management regime for Victoria's rail infrastructure.[89]

Safety

Main article: Rail Safety ActThe safety of tram operations in Melbourne is regulated by the Rail Safety Act 2006 which applies to all rail operations in Victoria.[90]

The Act establishes a framework containing safety duties for all rail industry participants and requires operators who manage infrastructure and rolling stock to obtain accreditation prior to commencing operations.[90][91] Accredited operators are also required to have a safety management system to guide their operations.[92] Sanctions applying to the safety scheme established under the Rail Safety Act are contained in the Part 7 of the Transport (Compliance and Miscellaneous) Act 1983.[93]

The safety regulator for the rail system in Victoria including trams is the Director, Transport Safety, whose office is established under the Transport Integration Act 2010.[88]

Rail operators in Victoria can also be the subject of no blame investigations conducted by the Chief Investigator, Transport Safety. The Chief Investigator is charged by the Transport Integration Act with conducting investigations into rail safety matters including incidents and trends.[94]

Ticketing and conduct

Ticketing requirements for trams in Melbourne are mainly contained in the Transport (Ticketing) Regulations 2006,[95] and the Victorian Fares and Ticketing Manual.[96]

Rules about safe and fair conduct on trams in Melbourne are generally contained in the Transport (Compliance and Miscellaneous) Act 1983[93] and the Transport (Conduct) Regulations 2005.[97]

See also

- Buses in Melbourne

- List of Melbourne tram routes

- List of tram and light-rail transit systems

- Railways in Melbourne

- Tram controls

- Trams in Australia

- Tramway Museum Society Of Victoria

- Transport Integration Act

- Rail Safety Act

- VicTrack

- Director of Public Transport

References

- ^ a b c "Facts & Figures". Yarra Trams. http://www.yarratrams.com.au/desktopdefault.aspx/tabid-47//74_read-117/. Retrieved 19 October 2011.

- ^ "Investing in Transport" (PDF). Department of Transport. p. 69. http://210.15.220.118/east_west_report/Investing_in_Transport_East_West-Chapter03.pdf. Retrieved 19 October 2011.

- ^ "Wien hat das fünftgrößte Straßenbahnnetz der Welt [Vienna has the fifth largest tramway network in the world]". Wiener Linien website. Wiener Linien. 2011. http://www.wienerlinien.at/wl/ep/contentView.do/contentTypeId/1001/channelId/-26075/programId/9419/pageTypeId/9081/contentId/25061. Retrieved 19 October 2011. (German)

- ^ "Facts & figures". Department of Transport. http://www.transport.vic.gov.au/pt/facts-and-figures/summary. Retrieved 19 October 2011.

- ^ "Glossary of terms". VICSIG. http://www.vicsig.net/index.php?page=trams§ion=glossary. Retrieved 19 October 2011.

- ^ "Metropolitan fares and tickets". Metlink. http://www.metlinkmelbourne.com.au/fares-tickets/metropolitan-fares-and-tickets/. Retrieved 19 October 2011.

- ^ "Turning". Vicroads. http://www.vicroads.vic.gov.au/Home/SafetyAndRules/RoadRules/Turning.htm. Retrieved 10 October 2011.

- ^ "Think Tram Program". Vicroads. http://www.vicroads.vic.gov.au/Home/Moreinfoandservices/PublicTransport/TramProjects/ThinkTramProgram.htm. Retrieved 19 October 2011.

- ^ "Tram priority & safety", Vicroads, http://www.vicroads.vic.gov.au/Home/Moreinfoandservices/PublicTransport/TramProjects/TramPriorityAndSafety.htm, retrieved 19 October 2011

- ^ a b c Russell Jones (2002). "Francis Boardman Clapp: transport entrepreneur". Friends of Hawthorn Tram Depot. http://www.hawthorntramdepot.org.au/papers/clapp.htm. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- ^ a b c "The Melbourne Tramway & Omnibus Company Limited" (PDF). TMSV Running Journal Vol9 No3. June 1972. http://www.tramway.org.au/runningjournal/rj_vol9_no3.pdf. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- ^ David Hoadley (8 January 1996). "Melbourne's cable trams". Trams of Australia. http://www.railpage.org.au/tram/cable.html. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- ^ Russell Jones (2004). "Northcote: the on again, off again cable tramway". Friends of Hawthorn Tram Depot. http://www.hawthorntramdepot.org.au/papers/northcote.htm. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- ^ a b "Melbourne & Metropolitan Tramways Board". Yarra Trams. http://www.yarratrams.com.au/desktopdefault.aspx/tabid-65/43_read-108/. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- ^ "Milestones, 1911 - 1920". Yarra Trams. http://www.yarratrams.com.au/desktopdefault.aspx/tabid-155/173_read-883. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- ^ "History of trains, trams and buses". Department of Transport. http://www.transport.vic.gov.au/pt/history-and-heritage/trains-trams-and-buses. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- ^ Robert Green (October 1989). "Australia’s first electric tram: the Box Hill to Doncaster tramway". Friends of Hawthorn Tram Depot. http://www.hawthorntramdepot.org.au/papers/boxhill.htm. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ^ a b "Milestones, 1901 - 1910". Yarra Trams. http://www.yarratrams.com.au/desktopdefault.aspx/tabid-155/173_read-884/. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ^ Russell Jones (2003). "Bent by name, Bent by nature". Friends of Hawthorn Tram Depot. http://www.hawthorntramdepot.org.au/papers/bent.htm. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ^ a b Russell Jones (2003). "VR electric street railways". Friends of Hawthorn Tram Depot. http://www.hawthorntramdepot.org.au/papers/vrtram.htm. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ^ Paul Nicholson (June-July 1969). "V.R. Tramway "Reminisences."". TMSV Running Journal. http://www.tramway.org.au/reflections.php?p=vr_tramway_reminisences. Retrieved 28 October 2010.

- ^ Arthur Stone (October-November 1969). "The Sandringham Tramway". TMSV Running Journal. http://www.tramway.org.au/reflections.php?p=the_sandringham_tramway. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- ^ "Did You Know?: Trams". City of Kingston. http://localhistory.kingston.vic.gov.au/htm/article/237.htm. Retrieved 03 June 2011.

- ^ Russell Jones (2008). "Steady as she goes: the Prahran & Malvern Tramways Trust". Friends of Hawthorn Tram Depot. http://www.hawthorntramdepot.org.au/papers/pmtt.htm. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ^ a b c Russell Jones (2009). "Alex Cameron: father of Melbourne’s electric trams". Friends of Hawthorn Tram Depot. http://www.hawthorntramdepot.org.au/papers/cameron.htm. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ^ Kathleen Thomson. "Cameron, Alexander (1864–1940)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. http://adbonline.anu.edu.au/biogs/A070534b.htm. Retrieved 4 November 2011.

- ^ a b "Melbourne & Metropolitan Tramways Board W Class No 380". Friends of Hawthorn Tram Depot. http://www.hawthorntramdepot.org.au/trams/mmtb380.htm. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ^ Russell Jones (2003). "Wattle Park: a tramway tradition". Friends of Hawthorn Tram Depot. http://www.hawthorntramdepot.org.au/papers/wattlepk.htm. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ^ a b Transport Demand Information Atlas, Vol 1

- ^ John Andrew Stone (2008). "Political factors in the rebuilding of mass transit" (PDF). Swinburne University of Technology. pp. 183-186. http://researchbank.swinburne.edu.au/vital/access/services/Download/swin:8497/SOURCE3. Retrieved 11 November 2011.

- ^ Photo ignites debate on tram fare evasion from abc.com.au

- ^ a b c "History of Yarra Trams". Yarra Trams. http://www.yarratrams.com.au/desktopdefault.aspx/tabid-60/38_read-103/. Retrieved 24 October 2011.

- ^ "About VicTrack". VicTrack. https://www.victrack.com.au/en/we-are-victrack/about-victrack. Retrieved 24 October 2011.

- ^ "Who's who in public transport". Department of Transport. http://www.transport.vic.gov.au/pt/management/whos-who-in-public-transport. Retrieved 24 October 2011.

- ^ a b c d "Metropolitan Transit Authority". Yarra Trams. http://www.yarratrams.com.au/desktopdefault.aspx/tabid-67/46_read-110/. Retrieved 24 October 2011.

- ^ "TRANSFIELD SERVICES/TRANSDEV PARTNERSHIP WITH THE STATE GOVERNMENT OF VICTORIA TO OPERATE THE ENTIRE MELBOURNE TRAM NETWORK" (Press release). Transfield Services. 19 February 2004. http://www.transfieldservices.com/icms_docs/29427_Transfield_ServicesTransdev_partnership_with_VIC_Govt_to_operate_entire_Melbourne_tram_network.pdf. Retrieved 24 October 2011.

- ^ "National Express - Pre Close statement". Interactive Investor. http://www.iii.co.uk/investment/detail/?display=news&code=cotn:NEX.L&action=article&articleid=4537089. Retrieved 24 October 2011.

- ^ Alistair Osborne (17 Dec 2002). "National Express walks out of Australian rail service". The Daily Telegraph. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/2836793/National-Express-walks-out-of-Australian-rail-service.html. Retrieved 24 October 2011.

- ^ "About Us". Yarra Trams. http://www.yarratrams.com.au/desktopdefault.aspx/tabid-20/258_read-1083/. Retrieved 19 October 2011.

- ^ Ian Hammond (October 2000). "Privatisation Boosts Rail Investment In Melbourne". International Railway Journal. http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0BQQ/is_10_40/ai_66931446/. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- ^ a b Ian Hammond (June 2001). "Melbourne Refurbishes to Improve Image:". International Railway Journal. http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0BQQ/is_6_41/ai_80898097/. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- ^ a b "NEW ERA FOR PUBLIC TRANSPORT STARTS TODAY" (Press release). OFFICE OF THE PREMIER. 12 October 2001. http://franklin.dpc.vic.gov.au/domino/Web_Notes/MediaRelArc02.nsf/0/0CB6751618ECE8244A256AE5008133D1?Open. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- ^ a b "NEW LOW-FLOOR TRAM HONOURS TRAMWAYS LEGEND" (Press release). MINISTER FOR TRANSPORT. 2 August 2002. http://franklin.dpc.vic.gov.au/domino/Web_Notes/MediaRelArc02.nsf/0/79B7C8A44C7671A04A256C0C0000D780?Open. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- ^ "A NEW IDENTITY FOR MELBOURNE’S PUBLIC TRANSPORT SYSTEM" (Press release). FROM THE MINISTER FOR PUBLIC TRANSPORT. 9 June 2003. http://franklin.dpc.vic.gov.au/domino/Web_Notes/newmedia.nsf/798c8b072d117a01ca256c8c0019bb01/861b4c03c1c2088fca256d410008cf92!OpenDocument. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- ^ "About Metlink". Metlink. http://www.metlinkmelbourne.com.au/about-metlink/. Retrieved 19 October 2011.

- ^ "MELBOURNE’S NEW TRAMLINE UNVEILED" (Press release). FROM THE OFFICE OF THE PREMIER. 2 May 2003. http://www.legislation.vic.gov.au/domino/Web_Notes/newmedia.nsf/bc348d5912436a9cca256cfc0082d800/9eab51baa5822b08ca256d1d00088a96!OpenDocument. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- ^ "Docklands Drive Tram Extension Now In Service" (Press release). Yarra Trams. 4 January 2005. http://www.yarratrams.com.au/desktopdefault.aspx/tabid-105/99_read-325. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- ^ "MAJOR PUBLIC TRANSPORT BOOST OPENS IN MELBOURNE’S EAST" (Press release). FROM THE MINISTER FOR PUBLIC TRANSPORT. 23 July 2005. http://www.legislation.vic.gov.au/domino/Web_Notes/newmedia.nsf/b0222c68d27626e2ca256c8c001a3d2d/77f706ecbd1cb0a2ca2570490003dfcc!OpenDocument. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- ^ "Bombardier Wins Contract for 50 Trams for One of the World's Largest Tram Operations in Melbourne, Australia" (Press release). Bombardier Transportation. 29 September 2010. http://www.bombardier.com/en/corporate/media-centre/press-releases/details?docID=0901260d80134862. Retrieved 19 November 2011.

- ^ "E Class". VICSIG. http://www.vicsig.net/trams/tram/e/v1. Retrieved 19 November 2011.

- ^ "330 and counting for platform stops" (Press release). Yarra Trams. June 2011. http://www.yarratrams.com.au/desktopdefault.aspx/tabid-39/44_read-2893/. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- ^ "Catch me, now you can!" (Press release). Yarra Trams. 15 August 2011. http://www.yarratrams.com.au/desktopdefault.aspx/tabid-39/44_read-2998/. Retrieved 4 November 2011.

- ^ a b c "Invitation to Tender - Melbourne Metropolitan Tram Franchise" (PDF). Department of Transport. p. 97. http://www3.transport.vic.gov.au/documents/MR3-IOT-Tram-Vol2.pdf. Retrieved 6 November 2011.

- ^ a b Clay Lucas (13 October 2010). "Bee trams to stay, but at what price?". The Age. http://www.theage.com.au/victoria/bee-trams-to-stay-but-at-what-price-20101012-16huk.html. Retrieved 6 November 2011.

- ^ a b "Melbourne's W-class tram". Trams of Australia. http://www.railpage.org.au/tram/w.html. Retrieved 6 November 2011.

- ^ a b "W Class Trams". National Trust of Australia. http://vhd.heritage.vic.gov.au/search/nattrust_result_detail/64262. Retrieved 6 November 2011.

- ^ "W CLASS TRAMS - BACKGROUND INFORMATION". National Trust of Australia. http://www.nattrust.com.au/content/download/81747/865020/file/Background_information.pdf. Retrieved 6 November 2011.

- ^ Ruth Williams (28 February 2010). "City not ready to lose its W-class act". The Age. http://www.theage.com.au/victoria/city-not-ready-to-lose-its-wclass-act-20100227-pa8v.html. Retrieved 6 November 2011.

- ^ Sarah-Jane Collins (22 January 2010). "Minister in, W-class trams out". The Age. http://www.theage.com.au/national/minister-in-wclass-trams-out-20100121-mo95.html. Retrieved 6 November 2011.

- ^ "W Class Trams". National Trust of Australia. http://www.nattrust.com.au/advocacy/campaigns/w_class_trams. Retrieved 6 November 2011.

- ^ Ruth Williams (7 March 2010). "Activist ready to rattle to keep W-class rolling". The Age. http://www.theage.com.au/victoria/activist-ready-to-rattle-to-keep-wclass-rolling-20100306-pptp.html. Retrieved 6 November 2011.

- ^ a b c d "Melbourne's Z-class tram". Trams of Australia. http://www.railpage.org.au/tram/z.html. Retrieved 6 November 2011.

- ^ "Z1 Class". VICSIG. http://www.vicsig.net/index.php?page=trams&class=Z1. Retrieved 6 November 2011.

- ^ "Z2 Class". VICSIG. http://www.vicsig.net/index.php?page=trams&class=Z2. Retrieved 6 November 2011.

- ^ "Z3 Class". VICSIG. http://www.vicsig.net/index.php?page=trams&class=Z3. Retrieved 6 November 2011.

- ^ "Melbourne's A-class tram". Trams of Australia. http://www.railpage.org.au/tram/a.html. Retrieved 6 November 2011.

- ^ "A1 Class". VICSIG. http://www.vicsig.net/index.php?page=trams&class=A1. Retrieved 6 November 2011.

- ^ "A2 Class". VICSIG. http://www.vicsig.net/index.php?page=trams&class=A2. Retrieved 6 November 2011.

- ^ "B1 Class". VICSIG. http://www.vicsig.net/index.php?page=trams&class=B1. Retrieved 6 November 2011.

- ^ a b "Melbourne's B-class tram". Trams of Australia. http://www.railpage.org.au/tram/b.html. Retrieved 6 November 2011.

- ^ a b "B2 Class". VICSIG. http://www.vicsig.net/index.php?page=trams&class=B2. Retrieved 6 November 2011.

- ^ "C Class". VICSIG. http://www.vicsig.net/index.php?page=trams&class=C&v=1. Retrieved 6 November 2011.

- ^ "C2 Class", VICSIG, http://www.vicsig.net/index.php?page=trams&class=C2, retrieved 6 November 2011

- ^ "D1 Class". VICSIG. http://www.vicsig.net/index.php?page=trams§ion=class&class=D1. Retrieved 6 November 2011.

- ^ "D2 Class". VICSIG. http://www.vicsig.net/index.php?page=trams§ion=class&class=D2. Retrieved 6 November 2011.

- ^ a b Ruth Williams (24 October 2010). "W-class trams: the art and soul of Melbourne town". The Age. http://www.theage.com.au/victoria/wclass-trams-the-art-and-soul-of-melbourne-town-20101023-16yne.html. Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- ^ Visit Victoria. "After Dark, Melbourne". YouTube. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=decaaQl5t_I. Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- ^ Beastie Boys. "Beastie Boys - The Rat Cage". YouTube. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GKQTEXWWtdQ&ob=av2n. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- ^ "Toorak Trams and Bernard Bolan". Trams Down Under. http://tdu.to/42011.msg. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- ^ Oscar the Band. "Taking the Tram (to Carnegie)". Bandcamp. http://oscartheband.bandcamp.com/track/taking-the-tram-to-carnegie. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- ^ "Songs From The 86 Tram". The Bedroom Philosopher. http://www.bedroomphilosopher.com/writing/lyrics/songs-from-the-86-tram/. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- ^ Melissa Mackereth (25 March 2006). "Last rides on the Karachi tram". Melbourne 2006 Commonwealth Games Corporation. http://www.melbourne2006.com.au/M2006/Homepage+News/20060325+Karachi+tram.htm. Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- ^ "The Flying Tram". Museum Victoria. http://museumvictoria.com.au/discoverycentre/infosheets/10458/. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- ^ "Royal Tram now in public service" (Press release). Yarra Trams. 26 October 2011. http://www.yarratrams.com.au/desktopdefault.aspx/tabid-39/44_read-3112/. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- ^ Michael Shmith (27 October 2011). "Not the Rolls or Bentley, but a commoner's conveyance gives Her Majesty a royal ride". The Age. http://www.theage.com.au/national/not-the-rolls-or-bentley-but-a-commoners-conveyance-gives-her-majesty-a-royal-ride-20111026-1mk4i.html. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- ^ "The Transport Integration Act. Overview" (PDF). Department of Transport. http://www.transport.vic.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0006/30849/clean-tia-fact-sheet-overview.pdf. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ^ "About us - Transport Integration Act". Department of Transport. http://www.transport.vic.gov.au/about-us/legislation/transport-integration-act. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ^ a b "About Transport Safety Victoria". Transport Safety Victoria. http://www.transportsafety.vic.gov.au/about-transport-safety-victoria. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ^ "Rail Management Act 1996". Government of Victoria. Australasian Legal Information Institute. http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/vic/consol_act/rma1996140/. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ^ a b "Overview of rail safety legislation". Transport Safety Victoria. http://www.transportsafety.vic.gov.au/rail-safety/acts-and-regulations/overview-of-rail-safety-legislation. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ^ "Overview of rail accreditation process". Transport Safety Victoria. http://www.transportsafety.vic.gov.au/rail-safety/accreditation/overview-of-rail-accreditation-process. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ^ "Safety management systems". Transport Safety Victoria. http://www.transportsafety.vic.gov.au/rail-safety/accreditation/how-to-become-accredited/safety-management-systems. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ^ a b "Transport (Compliance and Miscellaneous) Act 1983". Government of Victoria. Australasian Legal Information Institute. http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/vic/consol_act/tama1983385/. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ^ "About us - Office of the Chief Investigator". Department of Transport. http://www.transport.vic.gov.au/about-us/oci. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ^ "TRANSPORT (TICKETING) REGULATIONS 2006". Government of Victoria. Australasian Legal Information Institute. http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/vic/consol_reg/tr2006351/. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ^ "Victorian Fares and Ticketing Manual". Metlink. http://www.metlinkmelbourne.com.au/fares-tickets/victorian-fares-and-ticketing-manual. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ^ "TRANSPORT (CONDUCT) REGULATIONS 2005". Government of Victoria. Australasian Legal Information Institute. http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/vic/consol_reg/tr2005335/. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

External links

Official

- Official map of Melbourne's tram network

- Metlink - official website of Melbourne's public transport

- Yarra Trams

- 100 Years of Electric Trams in Melbourne (archive)

Enthusiast

- VICSIG - Victorian tramway infrastructure and rollingstock information

- Friends of Hawthorn Tram Depot - Articles

- Tramway Museum Society of Victoria - Reflections

- Melbourne's Trams To The Millennium

- Trams of Australia : history and current

- Unofficial Public Transport Guide to Melbourne

- Tram People Down Under: DVD Video Documentary

- Prince of Rails The IET. 2009-01-19.

- Geographically accurate map on Google Maps

Melbourne's public transport - Metlink Modes and network Ticketing Metropolitan rail operators Regional rail operators Metropolitan and regional bus operators Broadmeadows Bus Service • Cardinia Transit • Cranbourne Transit • Driver Bus Lines • Dyson's Bus Services • Eastrans • East West Bus Company • Grenda's • Hope Street Bus Line • Invicta Bus Services • Ivanhoe Bus Company • Kastoria Bus Lines • Martyrs Bus Service • Melbourne Bus Link • McKenzie's • Moonee Valley • Moorabbin Transit • Moreland Buslines • NationalBus • Panorama Coaches • Peninsula Bus Lines • Portsea • Reservoir • Ryan Brothers Bus Service • Sita Buslines • Skybus Super Shuttle • Sunbury Bus Service • Tullamarine Bus Lines • US Bus Lines • Ventura Bus Lines • WestransPlanned infrastructure Authorities Trams in Melbourne - Yarra Trams Routes Current Tram Fleet Operator Former operators Prahran and Malvern • Hawthorn • Melbourne, Brunswick and Coburg • Fitzroy, Northcote and Preston • Footscray • Northcote Municipality • North Melbourne Electric Tramway and Lighting Company • Melbourne and Metropolitan Tramways Board • Victorian Railways • M>Tram • Transdev TSLTourist services Tram depots Brunswick • Camberwell • East Preston • Essendon • Glenhuntly • Hawthorn • Kew • Malvern • North Fitzroy • Preston Workshops • Newport Workshops • Southbank • South MelbourneMiscellaneous Trams in Australia Cities Adelaide (Glenelg Tram) • Ballarat • Bendigo • Brisbane • Fremantle • Geelong • Hobart • Maitland • Melbourne • Newcastle • Perth • Sydney (Metro Light Rail)Operators Heritage Melbourne depots Malvern • Brunswick • Glenhuntly • Essendon • Camberwell • Southbank • KewSydney depots Fort Macquarie • RozelleCategories:- Landmarks in Melbourne

- Public transport in Melbourne

- Trams in Melbourne

- Light rail in Australia

- Tram transport in Australia

- 752 trams built in total 1923-1956, in service 1923–present

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.