- Idar-Oberstein

-

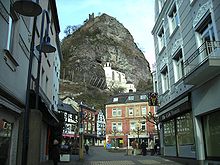

Idar-Oberstein Schloss Oberstein, castle on the hills above Oberstein

Coordinates 49°42′41″N 7°18′47″E / 49.71139°N 7.31306°ECoordinates: 49°42′41″N 7°18′47″E / 49.71139°N 7.31306°E Administration Country Germany State Rhineland-Palatinate District Birkenfeld Mayor Bruno Zimmer (SPD) Basic statistics Area 91.56 km2 (35.35 sq mi) Elevation 300 m (984 ft) Population 30,379 (31 December 2010)[1] - Density 332 /km2 (859 /sq mi) Other information Time zone CET/CEST (UTC+1/+2) Licence plate BIR Postal code 55743 Area codes 06781, 06784 Website www.idar-oberstein.de Idar-Oberstein is a town in the Birkenfeld district in Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany. As a Große kreisangehörige Stadt (large town belonging to a district), it assumes some of the responsibilities that for smaller municipalities in the district are assumed by the district administration. Today’s town of Idar-Oberstein is the product of two rounds of administrative reform, one in 1933 and the other in 1969, which saw many municipalities amalgamated into one. The various Stadtteile have, however, retained their original identities, which, aside from the somewhat more urban character encountered in Idar and Oberstein, tend to hearken back to each centre’s history as a rural village. Idar-Oberstein is known as a gemstone town, and also as a garrison town. It is also the largest town in the Hunsrück and has a population of around 30,000.

Contents

Geography

Location

The town lies on the southern edge of the Hunsrück on both sides of the river Nahe.

Constituent communities

The following are the divisions within the town of Idar-Oberstein as at 30 June 2005:

Centres merged in 1933 administrative reform

- Oberstein (8,794 inhabitants)

- Idar (8,466 inhabitants)

- Tiefenstein (2,642 inhabitants)

- Algenrodt (2,385 inhabitants)

Total population: 22,284

Centres merged in 1969 administrative reform

- Göttschied (2,924 inhabitants)

- Weierbach (2,703 inhabitants; area 751.6 ha)

- Nahbollenbach (1,970 inhabitants; area 821.7 ha)

- Mittelbollenbach (1,197 inhabitants; area 360.9 ha)

- Kirchenbollenbach (938 inhabitants; area 227.5 ha)

- Regulshausen (835 inhabitants)

- Enzweiler (747 inhabitants)

- Georg-Weierbach (709 inhabitants)

- Hammerstein (573 inhabitants; area 217.5 ha)

Total population: 12,596

Climate

Yearly precipitation in Idar-Oberstein amounts to 774 mm, falling into the middle third of the precipitation chart for all Germany. At 57% of the German Weather Service’s weather stations, lower figures are recorded. The driest month is April. The most rainfall comes in December. In that month, precipitation is 1.6 times what it is in April. Precipitation hardly varies at all and is evenly spread throughout the year. At only 13% of the weather stations are lower seasonal swings recorded.

History

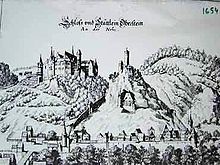

View of Oberstein according to Matthäus Merian

View of Oberstein according to Matthäus Merian

View of Oberstein, about 1875, oil painting by van Prouyen

View of Oberstein, about 1875, oil painting by van Prouyen

The territorial history of Idar-Oberstein’s individual centres is marked by a considerable splintering of lordly domains in the local area. Only in Napoleonic times, beginning in 1794, with its reorganization and merging of various territorial units, was some order brought to the traditional mishmash of local lordships. However, shortly thereafter, the Congress of Vienna brought the future town division once again, as the river Nahe became a border, and the centres on its north bank were thereby grouped into the Principality of Birkenfeld, an exclave of the Grand Duchy of Oldenburg, most of whose territory was in what is now northwest Germany, with a coastline on the North Sea.

The towns of Idar and Oberstein belonged to the Barons of Daun-Oberstein (who later became the Counts of Falkenstein) until 1670. In 1865, both Idar and Oberstein were granted town rights, and finally in 1933, they were forcibly united (along with the municipalities of Algenrodt and Tiefenstein) by the Nazis to form the modern town of Idar-Oberstein.

History up to French reorganization beginning in 1794

The constituent community of Oberstein grew out of the Imperially immediate Lordship of Oberstein. The Herren vom Stein (“Lords of the Stone”) had their first documentary mention in 1075, and their seat was at Castle Bosselstein, which is now known as the Altes Schloss (“Old Palatial Castle”), and which was above where later would be built the Felsenkirche (“Crag Church”) which itself was mentioned as early as the 12th century. The core of the area over which the lordship held sway was framed by the Nahe, the Idarbach, the Göttenbach and the Ringelbach. After 1323, the Lords of the Stone were calling themselves “von Daun-Oberstein”, and they managed to expand their lordly domain considerably, even into lands south of the Nahe and into the Idarbann. As the lordly seat with its castle and fortifications – remnants of the old town wall built about 1410 can still be seen “Im Gebück” (a prepositional phrase, but used as a proper name, in this case for a lane) – Oberstein could develop the characteristics of a town, without, however, ever earning itself the legal status of a market town (Flecken). In 1682, the Counts of Leiningen-Heidesheim, and in 1766 the Counts of Limburg-Styrum, became the owners of the Lordship of Oberstein, which largely shrank back to the above-mentioned lordly core after the Idarbann was ceded to the “Hinder” County of Sponheim in 1771. In 1776, the Margraves of Baden became the owners of the Lordship after the “Hinder” County of Sponheim was partitioned.

It is known from archaeological finds that human settlement in what is now Idar goes back to the very earliest times. The constituent community of Idar on the Nahe’s right bank belonged, as did the villages of Enzweiler, Algenrodt, Mackenrodt, Hettenrodt, Hettstein, Obertiefenbach and Kirschweiler, to the Idarbann. This area belonged mostly to the Lords of Oberstein, and it therefore shares a history with Oberstein; however, in some centres, notably Tiefenbach and Kirschweiler, some estates and rights were held by other lords, such as the Waldgraves and Rhinegraves and Tholey Abbey.

The constituent community of Tiefenstein arose from the merger of the villages of Tiefenbach and Hettstein in 1909. This Idarbann community’s territorial history is the same as Idar’s and Oberstein’s. Tiefenbach was mentioned as an estate in a 1283 document; a further documentary mention from 1051 cannot be related to the village with any certainty. Hettstein was mentioned as Henzestein or Hezerten in 1321 and had among its inhabitants Waldgravial subjects.

The village of Algenrodt had its first certain documentary mention as Alekenrod in a 1321 Oberstein enfeoffment document. In 1324, the Lords of Oberstein pledged it to the Waldgraves and Rhinegraves of Kyrburg. But for this, Algenrodt shares a history with the other Idarbann communities.

Enzweiler boasts traces of human habitation going back to Roman times. In 1276, Tholey Abbey owned a mill near Enzweiler. The village itself might have arisen in the 14th century, and it was always part of the Idarbann.

The village of Georg-Weierbach north of the Nahe, built in a way resembling terraces on land that falls steeply towards the river, likely goes back to the foundation of a church by Archbishop of Mainz Hatto II in the 10th century. In the 11th century, the village was mentioned in connection with the Lords of Wirebach (that is, Weierbach). In 1327, the village, which was for a short time held by the Lords of Randeck, was largely sold off to the Waldgraves and Rhinegraves and grouped into the Amt of Kyrburg. The form “Georg-Weierbach” stems from the church’s patron saint.

Göttschied, which had its first documentary mention in 1271, belonged together with Regulshausen, Gerach and Hintertiefenbach to Mettlach Abbey. These four villages were therefore known as the Abteidörfer (“abbey villages”), and in 1561, they were sold to the “Hinder” County of Sponheim.

Hamerzwiller (nowadays called Hammerstein) was mentioned in 1438 in a taxation book kept by the County of Sponheim, and had been held by the “Hinder” County of Sponheim as early as 1269, when that county enfeoffed the Counts of Schwarzenberg with it.

Regarded as the origin of the village of Kirchenbollenbach is the foundation of a church by Archbishop of Mainz Willigis sometime after 975. The earliest documentary evidence of the village goes back to 1128 when it was called Bolinbach. It is first known to have been a fief held by the Lords of Schwarzenberg from the Counts of Zweibrücken, whereafter it passed in 1595 to the Waldgraves and Rhinegraves if Kirn. One local peculiarity here was that a Catholic sideline of the otherwise mainly Protestant Rhinegraves ended up holding sway in Kirchenbollenbach, and under Prince Johann Dominik of Salm-Kyrburg, this line not only founded a new Catholic parish but also introduced a simultaneum at the local church.

The foundation stone of today’s village of Mittelbollenbach is said to be the estate of Bollenbach, which was mentioned in 1283 as a holding of the Lords of Oberstein in the area of the Winterhauch woodland. In 1432, the Dukes of Lorraine were enfeoffed with Nahbollenbach and Mittelbollenbach, which in the wake of the death of the last Lord of Oberstein led to bitter arguments over the complicated inheritance arrangements. Only in 1778 did Lorraine finally relinquish its claims in Electoral Trier’s favour.

Until 1667, Nahbollenbach and Mittelbollenbach shared the same history. Then, Nahbollenbach was acknowledged by Lorraine as an allodial holding of Oberstein, although beginning in 1682 it was an Electoral-Trier fief held by Oberstein.

The “abbey village” of Regulshausen belonged to Mettlach Abbey, who sold it in 1561 to the “Hinder” County of Sponheim. The oldest documentary mention comes from 1491.

The village of Weierbach – not to be confused with Georg-Weierbach mentioned above – had its first documentary mention in 1232 as Weygherbach, and belonged to the Amt of Naumburg in the “Further” County of Sponheim, which itself was later held by the Margraves of Baden, which gave the village its onetime alternative name, Baden-Weierbach. The oft-used other alternative name, Martin-Weierbach, stems from the church’s patron saint.

French, Oldenburg and Prussian times

After the French dissolved all the old lordships, they introduced a sweeping reorganization of territorial (and social) structure beginning in 1794. The whole area belonged to the arrondissement of Birkenfeld in the Department of Sarre. Until 1814, this was French territory. The introduction of the Code civil des Français, justice reform and, foremost, the abolition of the noble and clerical classes with the attendant end to compulsory labour and other duties formerly owed the now powerless lords quickly made French rule popular. However, there was quite a heavy tax burden imposed by the new rulers, and there was also continuing conscription of men into the French army. Both of these things weighed heavily on France’s Rhineland citizens.

After Napoleonic rule ended, the area was restructured. On the grounds of Article 25[2] of the concluding acts of the Congress of Vienna, the northern part of the Department of Sarre was at first given to the Kingdom of Prussia in June 1815.

Since Prussia was obliged under the terms of the 1815 Treaty of Paris to cede an area out of this parcel containing 69,000 inhabitants to other powers – 20,000 souls each to Saxe-Coburg and Gotha and the Duke of Oldenburg, along with smaller cessions to smaller princes – and since this had also been reconfirmed in Article 49[3] of the concluding acts of the Congress of Vienna, the region underwent further territorial division.

The villages south of the Nahe – Hammerstein, Kirchenbollenbach, Mittelbollenbach, Nahbollenbach and Martin-Weierbach – were therefore transferred in 1816 to the Principality of Lichtenberg, held by the Dukes of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. The Dukes were not satisfied with this territorial gain, and for their part, the people in the territory were not satisfied with their new rulers. In 1834, the area was sold for two million Thaler to Prussia and made into the Sankt Wendel district. Later, after the First World War, the Treaty of Versailles stipulated, among other things, that 26 of the Sankt Wendel district’s 94 municipalities had to be ceded to the British- and French-occupied Saarland. The remaining 68 municipalities then bore the designation “Restkreis St. Wendel-Baumholder”, with the first syllable of Restkreis having the same meaning as in English, in the sense of “left over”. The Prussians were themselves not well liked leaders, as they sometimes imposed their order with military might. They were known, and hated, for, among other things, putting a protest rally of the Hambach Festival in Sankt Wendel in May 1832, complete with a liberty pole in the Napoleonic tradition, to an end using military force, after Coburg had called on Prussia for help in the matter.

Idar, Oberstein, Tiefenstein, Algenrodt, Enzweiler, Georg-Weierbach, Göttschied, Enzweiler and Regulshausen became on 16 April 1817 part of the newly created Principality of Birkenfeld. They also became the Amt of Oberstein, which comprised the Bürgermeistereien (“Mayoralties”) of Herrstein, Oberstein and Fischbach. French law was allowed to stand. The Duke did, however, issue a Staatsgrundgesetz (“Basic State Law”) with which the people were not in agreement, because they would rather have stayed with Prussia. This continued work on the patchwork quilt of little states covering Germany was judged very critically in Idar and Oberstein, whereas Birkenfeld, which had as a result of the new political arrangement been raised to residence town, found little to complain about. The jewellery industry there, which even by this time had become national, perhaps international in scope, and indeed the jewel dealers themselves, who now found themselves living in a little provincially oriented town, perceived the new arrangement, though, as a backward step, particularly so after the years that France had ruled. It had had its worldly metropolis of Paris with its good business. The dealers, therefore, tried energetically, but without success, to have their land reannexed to Prussia. On the other hand, the Oldenburgers quickly managed to make themselves popular among the people by installing an unselfish government that established an independent judiciary and introducing various programmes that favoured farmers and the economy. A well regulated school system – in 1830, a public school was built in Oberstein – and the temporary suspension of military conscription only helped to support this positive picture. Roads were expanded and a postal coach service (for persons, bulk mailings and bulky goods) was set up. A further economic upswing was brought by the building of the Nahe Valley Railway, especially when the stretch from Bad Kreuznach to Oberstein opened on 15 December 1859.

Since the First World War

When the First World War ended, Grand Duke Friedrich August of Oldenburg abdicated, whereupon the Landesteil (literally “country part”) of Birkenfeld in the Free State of Oldenburg arose from the old principality. This Landesteil, along with the whole Rhineland, was occupied by the French on 4 December 1918. They did not withdraw until 30 June 1930.

At the Oldenburg Landtag elections in 1931, the NSDAP received more than 37% of the votes cast, but could not form the government. After the Nazis had first given up a declaration of tolerance for the existing government, they were then soon demanding that the Landtag be dissolved. Since this was not forthcoming, the Nazis filed suit for a referendum, and they got their way. This resulted in dissolution on 17 April 1932. In the ensuing new elections on 20 May, the Nazis won 48.38% of the popular vote, and thereby took 24 of the 46 seats in the Landtag, which gave them an absolute majority. In Idar, which was then still a self-governing town, the National Socialists received more than 70% of the votes cast. They could thereby already govern, at least in Oldenburg, with endorsement by the German National People's Party, which had two seats at its disposal, even before Adolf Hitler’s official seizure of power in 1933. One of the new government’s first initiatives was administrative reform for Oldenburg, which was followed on 27 April 1933 by the similar Gesetz zur Vereinfachung und Verbilligung der Verwaltung (“Law for simplifying administration and reducing its cost”) for the Landesteil of Birkenfeld. Through this new law, 18 formerly self-administering municipalities were amalgamated; this included the self-administering towns (having been granted town rights in 1865) of Idar and Oberstein, which were amalgamated with each other and also with the municipalities of Algenrodt and Tiefenstein to form the new town of Idar-Oberstein. The law foreshadowed what was to come: It would be applied within a few weeks, without further discussion or participation, to the exclusion of the public and against the will of municipalities, who had not even been asked whether they wanted it, to places such as Herrstein and Oberwörresbach, Rötsweiler and Nockenthal, or Hoppstädten and Weiersbach. The restructuring also afforded the Nazis an opportunity to get rid of some “undesirables”; under Kreisleiter (district leader) Wild from Idar, all significant public positions were held until Hitler’s downfall by Nazis.

In 1937, on the basis of the Greater Hamburg Act, the Landesteil of Birkenfeld was dissolved and transferred together with the “Restkreis St. Wendel-Baumholder” to the Prussian district of Birkenfeld,[4] a deed which put all of what are today Idar-Oberstein’s constituent communities in the same district.

After the Second World War, along with the whole district, the town’s whole municipal area passed to the then newly founded state of Rhineland-Palatinate.

On 1 April 1960, the town of Idar-Oberstein was declared a Große kreisangehörige Stadt (large town belonging to a district) by the state government, after the town itself had applied for the status.[5]

Amalgamations

In the course of administrative restructuring in Rhineland-Palatinate, nine surrounding municipalities were amalgamated with Idar-Oberstein. On 7 June 1969, the municipalities of Enzweiler, Göttschied, Hammerstein and Regulshausen were amalgamated, and on 7 November 1970 they were followed by Georg-Weierbach, Kirchenbollenbach, Mittelbollenbach, Nahbollenbach and Weierbach.

Before the administrative restructuring, there were extensive, sometimes behind-closed-doors talks by the then mayor of Idar-Oberstein, Dr. Wittmann, with offers of negotiation to all together 22 municipalities in the surrounding area. One of the reasons for this was a tendency that had been noted for people from Idar-Oberstein to move out of town to the surrounding municipalities, which were opening up extensive new building areas – among others Göttschied, Rötsweiler-Nockenthal and Kirschweiler – whereas within the town itself, given the problematic lie of the land, there were hardly any. The same problem saw to it that there was a dearth of land for industrial location. Surprising was the desire expressed by Weierbach, which came without one of Idar-Oberstein’s initiatives, to join the new greater town, for at the time, Weierbach did not even border on the town, and Weierbach itself was then foreseen as the future nucleus of its own greater municipality, or perhaps even town, together with the municipalities of Fischbach, Georg-Weierbach and Bollenbach, which would have been amalgamated with this municipality had the original plan come about.

With the exception of Georg-Weierbach, the proposal to amalgamate these villages with the town of Idar-Oberstein had notable majorities, either in the villages themselves or on their councils, in favour of dissolving their respective municipalities and then merging with the town. Nevertheless, bitter discussions and even administrative legal disputes arose in the former Amt of Weierbach, which was now bereft of its core municipalities. In April 1970, the Amt of Weierbach lodged a constitutional grievance with the Verfassungsgerichtshof Rheinland-Pfalz (Rhineland-Palatinate Constitutional Court), which ruled on 8 July 1970 that the state law for administrative simplification in Rhineland-Palatinate was in parts unconstitutional. The right to self-administration of the Amt of Weierbach, it furthermore ruled, was being infringed, and the municipal league’s vitality was being jeopardized. Thus, Weierbach, Georg-Weierbach, Nahbollenbach, Mittelbollenbach and Kirchenbollenbach were, with immediate effect, demerged from the town and reinstated as self-administering municipalities. After bitter arguments between the town of Idar-Oberstein together with the amalgamation supporters on the one side and the Amt of Weierbach together with the amalgamation opponents on the other, who promoted their views in demonstrations, at gatherings and in letter duels in newspaper correspondence pages, a poll was taken in early September 1970 with a vote in the Amt of Weierbach. The results favoured the state of affairs that had existed before the constitutional court’s ruling with almost 80% of the vote in favour of amalgamation, whereas the remaining municipalities in the Amt of Weierbach, namely Sien, Sienhachenbach, Schmidthachenbach, Fischbach, Zaubach (a village that vanished in the late 20th century) and Dickesbach, returned a vote of roughly 95% in favour of keeping the Amt of Weierbach.

With this expansion of the town, the centres of gravity in the Birkenfeld district had been shifted considerably. Idar-Oberstein could further grow as a middle centre: the educational facilities were expanded (Realschule, Heinzenwies-Gymnasium), new building developments could be opened up (especially in Göttschied, Regulshausen and Weierbach), land was available for a new hospital building and there was room, too, for industrial and commercial operations to locate.

Since Idar-Oberstein had not only a good general infrastructure but also, after the Steinbach Reservoir was brought into service, a more than adequate water supply, the option of amalgamating themselves with the town became attractive to many further municipalities. On the initiative of Mayor Wittmann, who had a survey done by an Osnabrück planning bureau on the town’s relationship with 25 other neighbouring municipalities, town council decided to promote the “unconditional amalgamation” of the municipalities of Fischbach, Dickesbach, Zaubach, Mittelreidenbach, Oberreidenbach, Schmidthachenbach, Sienhachenbach, Sien, Hintertiefenbach and Vollmersbach. The municipalities of Rötsweiler-Nockenthal, Siesbach, Gerach, Veitsrodt, Kirschweiler, Hettenrodt and Mackenrodt were each to receive an offer of amalgamation. The district administration in Birkenfeld then got involved, and it was decided by the district assembly (Kreistag) that Idar-Oberstein’s amalgamation policy, which was deemed to be reckless, should be censured. Since a certain disenchantment with all these amalgamations had meanwhile set in both in the outlying centres and in the town of Idar-Oberstein itself, all further initiatives either got nowhere or were shelved.

Schinderhannes

Idar-Oberstein has its connections with the notorious outlaw Johannes Bückler (1777–1803), commonly known as Schinderhannes. His parents lived in Idar around 1790, and Oberstein was the scene of one of his earliest misdeeds in 1796. He spent a whole Louis d'or on drinks at an inn. He had stolen it from an innkeeper named Koch from Veitsrodt who had meant to use it to buy brandy.[6]

Schinderhannes’s sweetheart, Juliana Blasius (1781–1851), known as “Julchen”, came from Idar-Oberstein’s outlying centre of Weierbach. She spent her childhood with her father and elder sister Margarethe as a “bench singer” and a fiddler at markets and church fêtes. At Easter 1800, Schinderhannes saw “Julchen” for the first time at the Wickenhof, a now vanished hamlet near Kirn, where the 19-year-old danced. Their relationship yielded a daughter and a son, Franz Wilhelm. After Schinderhannes was beheaded for his crimes in 1803, Juliana married first a gendarme, with whom she had seven children, and then after his death a livestock herder and day labourer.[7]

The Legend of the Felsenkirche (“Crag Church”)

According to legend, there were two noble brothers, Wyrich and Emich, who both fell in love with a beautiful girl named Bertha. The brothers lived at Castle Bosselstein, which stood atop a 135 m-high hill. Bertha was from a noble line that occupied the nearby Lichtenburg Castle.

Neither brother was aware of the other’s feelings for Bertha. When Wyrich, the elder brother, was away on some unknown business, Emich succeeded in securing Bertha’s affections and, subsequently, married her. When Emich announced the news to his brother, Wyrich’s temper got the better of him. In the heat of the moment, he hurled his brother out of a window of the castle and sent him to his death on the rocks below.

Wyrich was almost immediately filled with remorse. With the counsel of a local abbot, he began a long period of penance. At this time, Bertha disappears from the historical record. Many romantics feel that she died of a broken heart.

As Wyrich waited for a heavenly sign showing that he was forgiven, the abbot suggested that he build a church on the exact place where his brother died. Wyrich worked and prayed himself into exhaustion. However, the moment the church was completed, he received his sign: a miraculous spring opened up in the church.

Wyrich died soon after this. When the local bishop came to consecrate the new church, he found the noble lord dead on its steps. Wyrich was later placed in the same tomb with his brother.

Emigration and gemstones

Idar-Oberstein is known as a gemstone centre. Until the 18th century, the area was a source for agate and jasper. A combination of low-cost labour and energy helped the gemstone-working industry flourish. The river Nahe provided free water power for the cutting and polishing machines at the mills.

In the 18th century, though, gemstone finds in the Hunsrück were dwindling, making life harder for the local people. Many left to try their luck abroad. Some went as far as Brazil, where they found that gemstones could be recovered from open-pit mines or even found in rivers and streams. The locally common tradition of preparing meat over an open fire, churrasco, was also adopted by the newcomers and even found its way back to their homeland by way of gemstone shipping. Agate nodules were shipped back as ballast on empty vessels that had offloaded cargo in Brazil. The cheap agates were then transported to Idar-Oberstein.

In the early 19th century, many people were driven out of the local area by hunger and also went to South America. In 1827, emigrants from Idar-Oberstein discovered the world’s most important agate deposit in Brazil’s state of Rio Grande do Sul. As early as 1834, the first delivery of agate from Rio Grande do Sul had been made to Idar-Oberstein. The Brazilian agate exhibited very even layers, much evener that those seen in the local agates. This made them especially good for making engraved gems. Using locals’ technical knowledge of chemical dyes, the industry grew bigger than ever at the turn of the 20th century.

After the Second World War, the region had to redefine itself once more, and it developed into a leading hub in the trade of gemstones from Brazil and Africa. That in turn provided local artists with a large selection of material and the region experienced a “third boom” as a gemstone centre. More recently, however, competition from Thailand and India has hit the region hard.

Politics

Town council

The council is made up of 40 honorary council members, who were elected by proportional representation at the municipal election held on 7 June 2009, and the fulltime mayor (Oberbürgermeister) as chairman.

The municipal election held on 7 June 2009 yielded the following results[8]:

SPD CDU FDP Grüne Linke Freie Liste LUB Total 2009 12 11 7 2 2 3 3 40 seats Mayors

Ever since the state government declared the town of Idar-Oberstein a Große kreisangehörige Stadt (large town belonging to a district) on 1 April 1960, the town’s mayor has borne the official title of Oberbürgermeister.

In office from In office until Name Party Remarks 1920 1945 Ludwig Bergér Stadtbürgermeister in Oberstein 30 July 1933 Otto Schmidt Stadtbürgermeister in Idar 10 May 1945 29 April 1947 Walter Rommel Stadtdirektor (arrested and removed from office by French occupational forces) 22 September 1946 4 February 1949 Emil Lorenz Honorary Bürgermeister 5 February 1949 1953 Ernst Herrmann Fulltime Bürgermeister 15 December 1953 31 March 1960 Leberecht Hoberg CDU Bürgermeister 1 April 1960 8 April 1968 Leberecht Hoberg CDU Oberbürgermeister 1968 26 September 1974 Wilfried Wittmann SPD Voted out of office. 1977 28 February 1991 Erwin Korb SPD 1 March 1991 28 February 2001 Otto Dickenschied SPD 1 March 2001 28 February 2007 Hans Jürgen Machwirth CDU First directly elected Oberbürgermeister after the 1994 electoral reform. Machwirth resigned when he reached the maximum age allowed for elected municipal officials, 68, before his 8-year term had ended. 1 March 2007 28 February 2015 Bruno Zimmer SPD Directly elected on 5 November 2006. Idar-Oberstein’s chief mayor (Oberbürgermeister) is Bruno Zimmer.[9] He has a deputy mayor (Bürgermeister) named Frank Frühauf,[10] and their deputy (Beigeordneter) is Friedrich Marx.[11]

Coat of arms

The German blazon reads: Im halbrunden silbernen Schild befindet sich ein aufgerichteter roter Forsthaken, begleitet im rechten Obereck von einer sechsblättrigen roten Rose mit goldenem Kelch und grünen Kelchblättern, links unten von einer roten Eichel.

The town’s arms might in English heraldic language be described thus: Argent a cramp palewise sinister with a crossbar gules between in dexter chief a rose foiled of six of the second barbed and seeded proper and in sinister base an acorn slipped palewise of the second.

The charges are drawn from coats of arms formerly borne by both Idar and Oberstein before the two towns were merged in 1933. The current arms were approved by the Oldenburg Ministry of State for the Interior. The arms have been borne since 10 July 1934.[12]

Town partnerships

Idar-Oberstein fosters partnerships with the following places[13]:

Achicourt, Pas-de-Calais, France since 1966 (began in 1963 with outlying centre of Kirchenbollenbach)

Achicourt, Pas-de-Calais, France since 1966 (began in 1963 with outlying centre of Kirchenbollenbach) Les Mureaux, Yvelines, France since 1971

Les Mureaux, Yvelines, France since 1971 Margate, Kent, England, United Kingdom since 1981

Margate, Kent, England, United Kingdom since 1981

Culture and sightseeing

Buildings

The following are listed buildings or sites in Rhineland-Palatinate’s Directory of Cultural Monuments:[14]

Idar-Oberstein (main centre)

- Burg Oberstein, so-called Neues Schloss (“New Palatial Castle”; see also below) – first mention 1336, expansion in the 15th and 16th centuries; 1855 roof frame and interior destroyed by fire; originally a triangular complex; in the centre remnants of dwellings, among others the so-called Kaminbau (“Fireplace Building”) and the Esel-bück-dich-Turm (“Ass-stoop-down Tower”), both Gothic; of the bailey, possibly built later, remnants of the three towers

- Burg Stein or Bosselstein, so-called Altes Schloss (“Old Palatial Castle”), above the Felsenkirche (see also below) – first mention 1197, from the 15th century incorporated into the town fortifications, a ruin no later than the 18th century; in the northwest at the entrance and in the southwest of the girding wall remnants of dwellings, round keep

- Former Evangelical parish church, so-called Felsenkirche (“Crag Church”), Kirchweg (see also below) – on an irregular floor plan, built into a crag in 1482-1484, renovation of the Late Gothic vaulting with barrel vaulting, 1742, alteration to the tower roof, 1858, master builder Weyer, thorough renovation, 1927–1929, architect Wilhelm Heilig, Langen; polyptych altar from late 14th century, ascribed to the Master of the Mainz Mocking

- Evangelical parish church, Hauptstraße (see also below) – formerly St. Peter and Paul, cross-shaped aisleless church, 1751, expansion with transept 1894-1894, conversion 1955/1956, architect Hans Rost, Würzburg; Romanesque west tower (1114?), Baroque roof, possibly from 1712; gravestone M. C. Hauth, about 1742; in the graveyard a memorial to those who fell in the First World War

- Town fortifications – walling of Oberstein, incorporating the Felsenkirche, built of coarse volcanic rock, on the inside supported by buttresses, arose in 15th and 16th centuries; preserved parts: on the church hill halfway up to the Felsenkirche, tower Im Gebück (a lane) above Hauptstraße 476

- At Alte Gasse 5 – coat of arms of the former Imperial post office, 19th century

- Amtsstraße 2 – hospital and convent; three-floor Gothic Revival brick building, side risalto with chapel, 1900

- Austraße 6 – villa-style house with mansard roof, Renaissance Revival, two-floor conservatory, late 19th century

- Bahnhofstraße 1 – former “Centralhotel”; three-floor Historicist Revival corner building, echoes of Art Nouveau, 1905–1907, architects Gerhards & Hassert

- Bahnhofstraße 3 – sophisticated corner house, three-floor Baroque Revival building with mansard roof, echoes of Art Nouveau, 1908/1909, architect Hans Best, Kreuznach

- Klotzbergkaserne (“Klotzberg Barracks”), Berliner Straße, Bleidornplatz, Juterbogstraße, Klotzbergstraße, Ostpreußenstraße, Pestmüllerring, Pommernstraße (monumental zone) – barracks for two infantry battalions built in the course of Idar-Oberstein’s expansion into a garrison town during the Third Reich, buildings on terraced lands grouped about several yards and stairwells with staff buildings, houses for men, riding hall, partly quarrystone, 1936–1938; characterizes town’s appearance

- At Bismarckstraße 12 – stucco decoration on a residential and commercial house, about 1905

- Bismarckstraße 53 – Baroque Revival villa with mansard roof, 1910

- Dietzenstraße 30 – villa-style house with hipped roof, about 1910; characterizes town’s appearance

- Dietzenstraße 34 – picturesque-rustic villa, early 20th century

- Dietzenstraße 55 – residential and commercial house with several floors, Classicist Revival-Baroque Revival building with mansard roof, 1926

- Dr.-Liesegang-Straße 1 – former commercial hall; building of red brick framed with yellow sandstone, 1894/1895

- Dr.-Liesegang-Straße 3 – representative house, Art Nouveau motifs, about 1905; characterizes streetscape’s appearance together with no. 5

- Dr.-Liesegang-Straße 4 – cube-shaped villa with hipped roof, 1924

- Finsterheckstraße – water cistern, two-floor tower-type housing, rusticated, 1900

- Forststraße – memorial cross for Anne Freiin (Baroness) von Schorlemer, about 1905 (?); memorial stone, 1930

- Forststraße 26 – former hunting lodge; sophisticated country house in alternating materials typical of the time, last fourth of the 19th century

- Friedrich-Ebert-Ring 8 – picturesque-representative villa, 1903

- Friedrich-Ebert-Ring 10 – sophisticated villa, begun 1911, architect Julius Schneider

- Friedrich-Ebert-Ring 12–18 (monumental zone) – three sophisticated apartment blocks for French officers, 1922–1924, government master builder Metz; middle building, flanked by buildings with gable fronts that penetrate each other

- Friedrich-Ebert-Ring 59–65 (monumental zone) – four similar multi-family dwellings; three-floor cube-shaped buildings with hipped roofs on a retaining wall, 1924

- Georg-Maus-Straße 2 – former Schillerschule; mighty Baroque Revival housing, towards the back open like a cour d'honneur, 1908–1911, town master builder Müller; characterizes town’s appearance

- Hasenklopp 6 – palatial castle-type complex, Baroque Revival building with mansard roof, garden pavilion, swung retaining wall, 1921–1923, architect Paul Schultze-Naumburg

- Hauptstraße 260–274 (even numbers), Naßheckstraße 1, 3 (monumental zone) – group of villas, individually characterized buildings, some with great garden complexes, towards Naßheck smaller houses, many original enclosing fences, about 1905

- Hauptstraße 48 – corner residential and commercial house, iron framing with brickwork outside, Burbach Ironworks; characterizes streetscape’s appearance

- Hauptstraße 70 – former schoolhouse; three-floor cube-shaped building with hipped roof, so-called Oldenburg Late Classicism, 1856/1857, architect Peter Reinhard Casten, Birkenfeld; triangular gable after 1900, portal with balcony after 1933; characterizes town’s appearance

- At Hauptstraße 71 – stuccoed façade, 1922, of a three-floor residential and commercial house from 1888

- Hauptstraße 72 – representative three-floor house, Renaissance Revival motifs, in the back stable and barn, 1863/1864

- Hauptstraße 76 – four-floor residential and commercial house, New Objectivity, 1931, architect Johannes Weiler, Cologne

- Hauptstraße 78 – representative Historicist residential and commercial house, 1900, architect Hubert Himmes, Idar-Oberstein

- Hauptstraße 103 and 105 – house with mansard roof, 1852, remodellings in 1890 and 1905; in the back commercial building, 1912; whole complex in subdued Baroque Revival forms

- Hauptstraße 108 – lordly villa, Renaissance Revival motifs with Classicist tendencies, French country house style, 1870/1871, architect Louis Purper, Paris; in the back commercial buildings

- Hauptstraße 118 (see also below) – representative Renaissance Revival villa, 1894; nowadays the Deutsches Edelsteinmuseum (German Gemstone Museum)

- Hauptstraße 123 – representative villa with hipped roof, Art Nouveau décor, 1901, architect Hans Weszkalnys, Saarbrücken

- Hauptstraße 126 – representative residential and commercial house, possibly from the 1890s; in the gateway clay reliefs

- At Hauptstraße 129 – stately Gothic Revival entrance gate

- Hauptstraße 135 – villalike house, building of red brick framed with yellow sandstone, Renaissance Revival and Baroque Revival motifs, possibly about 1890

- Hauptstraße 143 – mighty three-floor house with mansard roof, 1910; characterizes town’s appearance

- Hauptstraße 145 – three-floor Historicist house, building of red brick framed with yellow sandstone, Renaissance Revival and Art Nouveau motifs

- Hauptstraße 147 – three-floor representative house, Baroque Revival, Louis XVI (early French Neoclassical) and Art Nouveau motifs, 1908

- Hauptstraße 148 – three-floor sophisticated house, Baroque Revival building with mansard roof, about 1900; whole complex with factory building and a further house in the back from 1910/1911

- Hauptstraße 149 – former “Hotel Fürstenhof”; red-brick building with plastered areas, Art Nouveau décor; 1904

- Hauptstraße 150 – small, elaborately shaped house, third fourth of the 19th century

- Hauptstraße 151 – house with entrance loggia, mansard roof, about 1910

- Hauptstraße 153 – picturesque-rustic villa, Gothic Revival motifs, about 1900

- Hauptstraße 155 – representative Renaissance Revival villa, 1894/1895, architect Massing, Trier

- Hauptstraße 156 – two-and-a-half-floor representative house, 1870/1871 and 1889

- Hauptstraße 162 – villalike house, 1893, architect Wilhelm Müller, Frankfurt; conversion 1929, architect Johannes Weiler, Cologne; wooden gazebo, lookout tower

- Hauptstraße 163 – Art Nouveau house, marked 1902, architect Hubert Himmes, Idar-Oberstein

- Hauptstraße 177 – house, Expressionistically varied Art Nouveau motifs, marked 1927/1928, architect Johannes Weiler, Cologne

- Hauptstraße 185 – bungalow, Expressionist motifs, 1923, architect Johannes Weiler, Cologne

- Hauptstraße 192 – picturesque-rustic villa, 1905; characterizes town’s appearance

- Hauptstraße 194 – villa with mansard roof, 1911, architect Paul Schultze-Naumburg; characterizes town’s appearance

- Hauptstraße 248 – country-house-style house with mansard roof, 1911, architect Georg Küchler, Darmstadt

- Near Hauptstraße 260 – unusual Art Nouveau fencing, 1904

- Hauptstraße 264 – sandstone villa with asymmetrical floor plan, Gothic Revival and Art Nouveau motifs, about 1905; décor

- Hauptstraße 270 – rustic villa, volcanic rock, sandstone, timber-frame, glazed brick, about 1905

- Hauptstraße 274 – villalike house, picturesquely nested plastered building with knee wall, 1905

- Hauptstraße 289 – meeting building of the lodge at the Felsentempel; symmetrically divided plastered building, Art Nouveau décor, 1906

- Hauptstraße 291 – house, sandstone-framed brick building with timber-frame parts, towards late 19th century, architect possibly Max Jager; conversion 1909 and 1914

- Hauptstraße 313 – bungalow with mansard roof, rustic and Expressionist motifs, 1923/1924, architect Julius Schneider; décor

- Hauptstraße 330 – corner house, 1882, architect R. Goering; décor

- Hauptstraße 332 – corner house, Classicist and Renaissance Revival motifs, third fourth of the 19th century

- Hauptstraße 337/339 – three-floor double house with mansard roofs, 1910/1911, architect Johannes Ranly, Oberstein

- Hauptstraße 338 – former Imperial post office, so-called Alte Post; mighty, three- and four-floor three-winged building with bell-shaped and timber-frame gables, 1910–1912, architect Postal Building Adviser Neufeldt; characterizes square’s appearance

- Hauptstraße 342/344 – double house, red sandstone building with mansard roof, Late Gothic and Art Nouveau motifs, 1900, architect Hubert Himmes, Idar-Oberstein

- Hauptstraße 385 – plastered building, echoes of Swiss chalet style with Baroque elements, 1950, architect Julius Schneider; built-in shop from time of building

- Hauptstraße 386 – former Pielmeyer department store; three-floor building with mansard roof, Louis XVI and Art Nouveau motifs, about 1905, architects Gerhards & Hassert; characterizes streetscape’s appearance

- Hauptstraße 391 – Renaissance Revival façade of a residential and commercial house, 1890; characterizes streetscape’s appearance

- Hauptstraße 412/414 – Baroque double house with timber-frame gable, marked 1702

- Hauptstraße 417 – three-floor residential and commercial house, Art Nouveau motifs, 1906, architect Max Jager; characterizes square’s appearance

- (an) Hauptstraße 418 – elaborate façade décor, Art Nouveau with Baroque elements, about 1905

- Hauptstraße 432 – three-floor timber-frame building, partly solid, late 16th century, conversion 1717

- Hauptstraße 434 – three-floor residential and commercial house with mansard roof, Renaissance Revival motifs, 1895; characterizes town’s appearance

- Hauptstraße 468/470 – mighty three-floor balloon frame building, earlier half of the 15th century

- Hauptstraße 499 – house with mansard roof, Baroque Revival plaster décor, late 19th century

- Hauptstraße 281–309 (odd numbers) (monumental zone) – mostly two-floor residential and commercial buildings in an almost closed row giving the effect of a unified streetscape, 19th and early 20th centuries; brick with sandstonework parts, plastered, timber-frame, in parts of the back factory buildings; pattern broken somewhat by two villalike houses (no. 303 Baroque Revival, 1905; no. 309, possibly from 1890)

- Höckelböschstraße 1 – three-floor Baroque Revival corner residential and commercial house, about 1908; décor; characterizes town’s appearance

- Höckelböschstraße 2 – row house with mansard roof, early 20th century

- Höckelböschstraße 8 – house, Renaissance Revival motifs, about 1877

- Hoher Weg 1/3 – double house, three-floor building with mansard roof on a retaining wall, 1912, architect Johannes Ranly; characterizes town’s appearance

- Kasinostraße 7 – building of the former Hermann Leyser cardboard packaging factory; brick building, partly timber-frame, filigree wood details, late 19th century; house 1896, wing joining the two 1911

- Keltenstraße – water cistern; representative front building with brickwork walls, 1894

- Kobachstraße 4 – sophisticated residential and commercial house, Louis-XVI-style, 1912

- Luisenstraße 9 – rustic villa, bungalow with mansard roof on an irregular floor plan, 1908, architect Georg Küchler, Darmstadt

- Mainzer Straße 64 – villa, Art Nouveau décor, 1907

- Mainzer Straße 66 – representative Art Nouveau villa, 1905, architects Hubert Himmes and Adrian Wehrli, Idar-Oberstein

- Mainzer Straße 69 – representative Art Nouveau villa with mansard roof, about 1905

- Mainzer Straße 73 – representative villa on an asymmetrical floor plan, Art Nouveau décor with Baroque elements, 1905/1906, architect Hans Weszkalnys, Saarbrücken

- Mainzer Straße 75 – plastered villa on an asymmetrical floor, hipped roofs, 1901, architect Hubert Himmes, Idar-Oberstein

- Mainzer Straße 224 – Villa Wolff, sophisticated rustic villa, bungalow with mansard roof, 1923/1924, architect Julius Schneider

- Mainzer Straße 56/58, 60, 64, 66, 69, 73, 75, 77, Dr.-Liesegang-Straße 1, Hauptstraße 123 (monumental zone) – Idar-Oberstein’s only mainly closed villa neighbourhood, villas in gardens, about 1900 to the 1920s; partly with sprightly roof profiles, Late Historicism, Art Nouveau, architecture of the 1920s; on the squarelike widening at the south end of Mainzer Straße the commercial hall (Dr.-Liesegang-Straße 1, see above)

- Otto-Decker-Straße 6 – three-floor Gothic Revival residential and commercial house with mansard roof, 1900, architect Hubert Himmes, Idar-Oberstein

- Otto-Decker-Straße 12 – villalike corner house, Renaissance Revival motifs, 1895–1896, architect Heinrich Güth, Saarbrücken

- Otto-Decker-Straße 16 – Historicist residential and commercial house with mansard roof, 1905

- Pappelstraße 1, 2, 3 (monumental zone) – so-called Franzosenhäuser (“Frenchman’s Houses”), group of three houses built by the town for French officers in the occupational forces; buildings with tent roofs, Expressionist motifs, begun in 1920, architect Wilhelm Heilig, Langen

- Ritterstraße 11 – house, after 1882, Baroque Revival expansion 1912

- Ritterstraße 31 – row house with mansard roof, Renaissance Revival motifs, marked 1906

- Schönlautenbach 6 – representative house, three-sloped hipped roof, 1924/1925, architect Johannes Weiler, Cologne

- Schönlautenbach 27 – house with mansard roof, timber-frame bungalow on terracelike stone lower floor, 1928

- Oberstein Jewish graveyard, Seitzenbachstraße (monumental zone) – laid out possibly in the 17th century, expanded in 1820, older part dissolved in 1945; gravestones placed since the mid 19th century in the newer section’s wall; memorials mainly sandstone or granite, obelisks, steles; behind Kirchhofshübel 14 further gravestone fragments and wall settings; originally belonging to the graveyard the former Jewish mortuary (Seitzenbachstraße – no number – today a workshop), central building with pyramid roof, built in 1914

- Seitzenbachstraße/Hauptstraße, Niederau Christian graveyard (monumental zone) – three-part parklike complex, laid out from 1836 to 1916; soldiers’ graveyard 1914/1918; warriors’ memorial 1914/1918 and 1939/1945, memorial stone for Jewish fellow inhabitants placed after 1945; hereditary gravesites: no. 1 crypt with Egyptian-style entrance; no. 3 polygonal Gothic Revival column; nos. 7 and 8 several gravestones, granite slabs, granite steles, bronze urns; no. 29 complex of Kessler & Röhl, Berlin, sculpture by H. Pohlmann, Berlin; no. 32 angel with anchor by P. Völker; no. 33: marble angel

- Tiefensteiner Straße, Idar Christian graveyard (monumental zone) – laid out in 1869 in “Mittelstweiler”, first documented in 1871, enlarged several times; since 1969 newer main graveyard to the west “Im Schmalzgewann”; warriors’ memorial 1870/1871: roofed stele with relief, surrounded by eight limetrees; fencing with Baroque Revival entrance possibly from about 1900; graveyard chapel, yellow sandstone building, towards 1908; warriors’ memorial in graveyard of honour for those who fell in 1914/1918, 1920; graveyard for those who fell in 1939/1945 by Max Rupp, Idar-Oberstein, and Theodor Siegle, Saarbrücken, 1961; several elaborate hereditary gravesites

- Tiefensteiner Straße 20 – country-house-style house, bungalow with half-hipped roof, 1920s

- Wasenstraße 1 – three-floor residential and commercial house with Historicist elements, partly decorative timber-frame, conversion 1924/1925

- Wilhelmstraße 23 – representative manufacturer’s villa with mansard roof, Baroque Revival motifs with Classicist elements, begun in 1909, architect Julius Schneider

- Wilhelmstraße 44 – manufacturer’s house with garden; sandstone-framed volcanic rock building, Art Nouveau décor, 1910, architect Max Jager; décor

- Wilhelmstraße 48 – three-floor Historicist residential and commercial house, sandstone-framed brick building, 1903, in the back factory building; characterizes town’s appearance

- Wilhelmstraße 40/42, 44, 46, 48, 49–51 (monumental zone) – complex of dwelling and manufacturing buildings around the Jakob Bengel metalware factory (long, two- and three-floor commercial buildings, entrepreneur’s villa (no. 44), 1873 to 1906

- Bismarckturm (Bismarck Tower), east of Idar on the Wartehübel – monumental complex built out of volcanic rock, 1907, architect Hans Weszkalnys, Saarbrücken (design by Wilhelm Kreis, Dresden)

- Railway bridge on the Rhine-Nahe Railway, on the east side of the Altenberg – three-arch bridge in the Nahe valley at the Altenberg

- Railway bridges on the Rhine-Nahe Railway, west of the railway station – two brick-framed sandstone-block structures over a bend in the Nahe

- Railway bridge on the Rhine-Nahe Railway, at the Wüstlautenbach – partly heavily renovated three-arch, brick-framed sandstone-block structure over the valley of the Wüstlautenbach

Algenrodt

- Im Stäbel – entrance relief at the Straßburgkaserne (“Strasbourg Barracks”) – forms characterized by National Socialism, 1936–1938; on the corner of Saarstraße a memorial, 1958

- Im Stäbel, graveyard – memorial for those who fell in the First World War by Wilhelm Heilig, about 1920

Enzweiler

- Railway bridge and tunnel on the Rhine-Nahe Railway, east of Enzweiler – two-arch bridge, volcanic rock and brick, over the Nahe, impressive sequence of Hommericher Tunnel, bridge and Enzweiler Tunnel

Georg-Weierbach

- Former Evangelical parish church, Auf der Burr – formerly Saint George’s, stepped Romanesque building, west tower, quire Late Gothic altered (possibly in the 14th century), aisleless nave remodelled in Baroque; Marienglocke (“Mary’s Bell”) from 1350; in the graveyard gravestones about 1900

- Near Auf der Burr 13 – lift pump, cast-iron, brass, Gothic Revival, firm of Gebrüder Zilken, Koblenz, possibly from the last fourth of the 19th century

- Before Buchengasse 2 and 4 – two wrought-iron wells

Göttschied

- Evangelical church, Göttschieder Straße 43 – aisleless church with ridge turret, portal marked 1620, remodellings in 1775, 1864/1865 and 1933

Hammerstein

- Evangelical church, Hammersteiner Straße 39 – Baroque Revival aisleless church with ridge turret, 1904–1909, architect August Senz, Düsseldorf; characterizes town’s appearance

- Railway bridge and tunnel on the Rhine-Nahe Railway, northwest of Hammerstein – two-arch brick-framed sandstone-block structure over the Nahe, tunnel through the so-called Hammersteiner Kipp

Kirchenbollenbach

- Former Catholic Parish Church of John of Nepomuk (Pfarrkirche St. Johann Nepomuk), Am Kirchberg 3 – two-naved Late Historicist quarrystone building, flanking tower, 1895–1898, architect Ludwig Becker, Mainz; spolia (18th century); rich décor

- Evangelical parish church, Am Kirchberg 6 – plain Baroque aisleless church, ridge turret with helmed roof, 1755, architect Johann Thomas Petri, Kirn; décor

- Am Kirchberg 8 – former Catholic rectory; one- and two-floor Baroque building with hipped roof, 1770, architect possibly Johann Thomas Petri; characterizes town’s appearance

- Am Kirchberg 3, 6, 8 (monumental zone) – group made up of the Catholic Church (Am Kirchberg 3) and the Evangelical church (Am Kirchberg 6) with the former rectory (Am Kirchberg 8), forecourt with altars (made of spolia), across the street, documents the village’s ecclesiastical development

- Auf dem Rain 21 – former school; nested Swiss chalet style building with Expressionist details, 1926/27

- At Im Brühl 1 – wooden door, Zopf style, 18th century

Mittelbollenbach

- Im Schützenrech 57 – school; sandstone-framed plastered building penetrated by gable risalti, 1912, expansion 1962

- In der Gaß 3 – former bull shed; one-floor solid building with timber-frame knee wall, possibly from about 1910; equipment

Nahbollenbach

- Jewish graveyard, Sonnehofstraße (monumental zone) – ten mostly stele-shaped stones, 1900 to about 1933, in fenced area

Tiefenstein

- Bachweg 6 – Quereinhaus (a combination residential and commercial house divided for these two purposes down the middle, perpendicularly to the street), partly timber-frame (plastered), possibly from the earlier half of the 19th century

- Granatweg – warriors’ memorial; sandstone relief, 1920s, concrete stele inserted after 1945

- Tiefensteiner Straße 87 – Kallwiesweiherschleife; water-driven gemstone-cutting mill; squat building with gable roof and great iron-bar windows, 18th century, converted or renovated several times; equipment; pond

- Tiefensteiner Straße 178 – Hettsteiner Schleife or Schleife zwischen den Mühlen; former water-driven gemstone-cutting mill; quarrystone building with great iron-bar windows, 1846; equipment

- Near Tiefensteiner Straße 232 – former filling station, filling station building with sales room and workshop, mushroom-column construction with broad overlying roof, 1950s

- Tiefensteiner Straße 275 – villalike house with contemporary details, 1920s

- Tiefensteiner Straße 296 – avant-garde house, 1930/1932, architect Julius Schneider

- Tiefensteiner Straße 322 – villalike house with mansard roof, Louis XVI and Art Nouveau motifs, shortly after 1900

Weierbach

- Evangelical parish church, Obere Kirchstraße – formerly Saint Martin’s, Early Classicist aisleless church, architect Wilhelm Frommel, 1792/1793; late mediaeval tower altered in the 17th century; retaining wall possibly mediaeval

- Saint Martin’s Catholic Parish Church (Pfarrkirche St. Martin), Obere Kirchstraße – Gothic Revival red sandstone building, 1896/1897, architect Lambert von Fisenne, Gelsenkirchen; décor; characterizes town’s appearance

- Across from Dorfstraße 1 – so-called Hessenstein; former border stone; Tuscan column with inscription and heraldic escutcheon, after 1815

- Dorfstraße 32 – former Evangelical rectory; building with half-hipped roof, Swiss chalet style, 1930/1931, architect Friedrich Otto, Kirn; characterizes streetscape’s appearance

- Weierbacher Straße 12 – house, used partly commercially, with mansard roof, Expressionist motifs, 1920s

- Weierbacher Straße 22 – railway station; reception and administration building with employee dwellings, goods hall and side building, 1913/1914, architect Schenck; one- and two-floor main building, Art Nouveau décor with Classicist elements, monumental roof profile

- Weierbacher Straße 75 – former Amtsbürgermeisterei; asymmetrically divided plastered building, Renaissance Revival motifs, 1910/1911

- Jewish graveyard, east of the village on the hilltop “Am Winnenberg” (monumental zone) – seven stelelike stones or pedestals

- Niederreidenbacher Hof, northeast of the village (monumental zone) – first mention of a castle in the 13th century, in the 19th century an estate, from 1904 a deaconess’s establishment, with dwelling and commercial buildings, mill and distillery, about 1840 and thereafter; crag cellar under the estate; conversions and expansions 1904 and thereafter; chapel, 1658 or older, expansion 1931; Imperial Baron Friedrich Kasimir Boxheim’s (d. 1743) gravestone; remnants of the graveyard belonging to the establishment; two water cisterns, 1930s; park and garden facilities, characterizes landscape’s appearance

Mediaeval buildings

Felsenkirche

The famous Felsenkirche (“Crag Church”) is the town’s defining landmark. It came to be through efforts by Wirich IV of Daun-Oberstein (about 1415–1501), who in 1482 built the now Protestant church on the foundations of the Burg im Loch (“Castle in the Hole”).

As far as is now known, this castle was the first defensive position held by the Lords of Stein and a refuge castle for the dwellers of the village down below that was built into the great cave in the crag, the “Upper Stone” (or in German, Oberer Stein) on the river Nahe. This, of course, explains the origin of the name “Oberstein”.

The “Castle in the Hole” was the only cave castle on the Upper Nahe. The Felsenkirche can nowadays be reached by visitors through a tunnel that was built in modern times.

Castle Bosselstein

Up above the small church, on a knoll (Bossel) stands Castle Bosselstein, or rather what is left of it. The whole complex was forsaken in 1600, and all that stands now is a tower stump and remnants of the castle wall. In the Middle Ages, it was a stronghold to be reckoned with, with its two crescent moats and its two baileys.

Somewhat farther up, not far from Castle Bosselstein, the third castle arose about 1325, the one now known as Schloss Oberstein. Until 1624, it was the residence of the Counts of Daun-Oberstein. In 1855 it burnt down. In the years 1926 to 1956, the castle was used as a youth hostel, and thereafter as an inn.

In 1961, part of the east wall fell in. The castle club, Schloss Oberstein e. V., that was founded shortly thereafter, in 1963, has been worrying ever since about maintaining the acutely endangered building materials that make up this former four-tower complex. In 1998, the town of Idar-Oberstein became the castle’s owner. Today there is once again a small inn, the Wyrich-Stube, and there are also now a few rooms restored by the castle club, which can be hired for festive occasions or cultural events.

St. Peter und Paul

St. Peter und Paul is the Catholic Church in the constituent community of Idar. It was built in 1925 as a wooden church for the then town of Idar. Since the 17th century, the town’s Catholics had had to make do with ecclesiastical services from Oberstein. By 1951, the church had fallen into such disrepair that it was extensively converted and expanded with stone.

Theatre

Besides the Town Theatre in the constituent community of Oberstein, there is also a cabaret stage. With Schloss Oberstein as the backdrop, the Theatersommer Schloss Oberstein (“Schloss Oberstein Theatre Summer”) is held each year.

Museums

Since the early 1960s tourism has grown in importance for Idar-Oberstein. Today it boasts a number of modern facilities such as the Steinkaulenberg, a gemstone mine open to visitors, and the German Gemstone Museum, as well as several recreational resorts. Nationally known is the Deutsches Edelsteinmuseum (German Gemstone Museum) in the constituent community of Idar, which boasts many gemstone exhibits.

The Museum Idar-Oberstein in the constituent community of Oberstein right below the famous Felsenkirche devotes itself to the specialized theme of “minerals”, and accordingly shows not only local places where gems were discovered, but also worldwide discovery places. The Idar-Oberstein jewellery industry and gemstone processing, too, and especially the agate-cutting operation, are presented in an impressive way.

Insights into the production of Art Deco jewellery as it was done about the turn of the 20th century are offered by the Industriemuseum Jakob Bengel in the constituent community of Oberstein. It is open the year round.

At the Steinkaulenberg gemstone mines, the only gemstone mine in Europe open to visitors, and at the Historische Weiherschleife – a gemstone-grinding mill – one can learn a few things about gemstone processing and Idar-Oberstein’s history. Jasper is also featured there, for Idar-Oberstein is also an important centre for that semiprecious stone.

Sport

The town’s best known sport club is SC 07 Idar-Oberstein.

Idar-Oberstein has an indoor swimming pool and, since September 2005 an outdoor swimming pool fed by natural water. On the town’s outskirts, a Friends of Nature house has been established, offering cyclists, hikers and tourists meals and lodging. Also, in nearby Kirschweiler is a golf course.

The Schleiferweg (Schleifer is German for “grinder” or “polisher”, a reference to the town’s fame as a gem-processing centre; Weg simply means “way”) is a 22 km-long signposted hiking trail round Idar. The path leads around the constituent communities of Idar, Oberstein, Göttschied, Algenrodt and Tiefenstein. Especially for sophisticated hikers, the Schleiferweg offers a special hiking experience with a high section of path through thick forest. The trail leads by various tourist attractions, such as the Weiherschleife, the Steinkaulenberg, the Kammerwoog (lake) or even the Wäschertskaulen spit roast house. With the good links to the town transport network, the trail can be broken up into as many shorter stretches as the hiker chooses.

Regular events

- The New Year’s Gala Concert of the Symphonisches Blasorchester Obere Nahe e. V. (wind orchestra) has been seeing the town into the New Year culturally since 1991.

- The International Trade Fair for Gemstones, Gemstone Jewellery and Gemstone Objects is held yearly in September and October (see also below).

- The regional consumer fair, better known as Idar-Obersteiner Wirtschaftstage, was created by the Wirtschaftsjunioren Idar-Oberstein 2003, and is growing into a true success story. It was organized and staged from 2003 to 2005 by the Wirtschaftsjunioren.

- The Deutsche Edelsteinkönigin (“German Gemstone Queen”) is chosen every other year from the region of the Deutsche Edelsteinstraße (“German Gem Road”).

- The Spießbratenfest (“Spit Roast Festival”) has been held since 1967 each year from the Friday to Tuesday that includes the last Sunday in June. It is said to be the biggest folk festival on the Upper Nahe.

- The Kinderkulturtage (“Children’s Cultural Days”) have been being held for several years now as a successor festival to the Kinderliederfestival (“Children’s Song Festival”). There are 15 to 20 events for children, youth and those who are young at heart.

- Each year in early June, the Jazztage (“Jazz Days”) are held. Appearing here are regional and national jazz greats on several stages in the Idar pedestrian precinct.

- Diamond grinders, facet and surface grinders and agate grinders demonstrate the most varied working techniques within the framework of the Deutscher Edelsteinschleifer- und Goldschmiedemarkt (“German Gemstone Grinders’ and Goldsmiths’ Market”). Goldsmiths and jewellery designers allow a look at their creative work in Oberstein’s historic town centre below the Felsenkirche.

- The Kama Festival was held from 1991 to 2007 on the lands of the Kammerwoog Conservation Area at Whitsun. It was the biggest open-air festival in Idar-Oberstein. The last festival took place in much reduced form in 2008.

Culinary specialities

Spießbraten (spit roast)

A distinction is made between Idarer Spießbraten and Obersteiner Spießbraten. The former is a kind of Schwenkbraten, whereas the latter is a kind of rolled roast. Spießbraten is rooted fast among Idar-Oberstein’s and the surrounding region’s culinary and cultural customs

When making the more often consumed Idarer Spießbraten, the meat – originally prime rib, today often also roast beef or pork neck – is laid the day before cooking in raw onions, salt and pepper. The onions are good to eat while cooking at the fire with a beer. Locals favour beechwood for the fire, to give the roast its traditional flavour.

The variations on the Spießbraten recipe is also the subject of the town’s slogan, which bears witness to a patronizing cosmopolitanism: Rossbeff fa die Irader, Kamm fa die Uwersteener und Brot für die Welt – dialectal German for “Roast beef for the Idarers, pork neck for the Obersteiners and bread for the world.”

Fillsel

This is toast, minced meat, diced bacon, leek, eggs, salt and pepper.

Gefillte Klees (filled dumplings)

This is coarse potato dumplings (made from raw potatoes) filled with Fillsel with a bacon sauce.

Kartoffelwurst (potato sausage)

Also dialectally called Krumbierewurscht, this was formerly “poor people’s food”, but today it is a speciality. Potatoes, pork, beef and onions are put through the mincer and seasoned with savoury, pepper and salt. It can be fed into the traditional gut, preserved in a jar or even eaten straightaway.

Murde on Klees (carrots and dumplings)

This is raw potato dumplings cooked and served together with carrots (sometimes known in German as Mohrrüben, or dialectally in Idar-Oberstein as Murde) and pickled or smoked pork.

Riewe on Draehurjel

This is beetroots with roast blood sausage.

Dibbelabbes

This is made by roasting Kartoffelmasse (potatoes, bacon, eggs, flour, salt and pepper) in a Dibbe (cast-iron roasting pan).

Schaales

This is Kartoffelmasse (the same as for Dibbelabbes) baked in a Dibbe in the oven with dried meat.

Economy and infrastructure

All together, Idar-Oberstein has roughly 219.3 ha of land given over to commerce. Three other areas in town, Dickesbacher Straße, Finkenberg Nord and Am Kreuz, hold a further 28 ha in reserve for economic expansion. The town also has at its disposal the rezoning area Gewerbepark Nahetal in the outlying centre of Nahbollenbach, comprising 23 ha.

The Bundesverband der Diamant- und Edelsteinindustrie e. V. (“Federal Association of the Diamond and Gemstone Industry”) has its seat in Idar-Oberstein. It represents the industry’s interests in dealings with lawmakers as well as federal, state and municipal representatives. It advises members in areas such as environmental protection, problems in competition, questions of nomenclature and so forth, and makes the necessary contacts as needed. To promote the designing and quality of jewellery and gemstones, the Association created the international competition revolving about the German Jewellery and Gemstone Prize.

The Deutsche Diamant- und Edelsteinbörse e. V. (“German Diamond and Gemstone Exchange”) was opened in 1974 as the world’s first combined exchange for diamonds as well as coloured gemstones. It is one of the 25 exchanges in the World Federation of Diamond Bourses.

The firm Klein & Quenzer was among the best known producers of costume jewellery before it rose to become the biggest manufacturer of German medals and decorations during the two world wars.

The Wirtschaftsjunioren Idar-Oberstein were founded in 1972. Entrepreneurs and senior management join in this organization for economic, cultural and social purposes in the region.

The cookware manufacturer Fissler has its headquarters in town. The company became well known for its invention of the mobile field kitchen in 1892. Giloy und Söhne, one of Europe’s biggest diamond jewellery manufacturers, has its headquarters here, too.

For more than 20 years now, the International Trade Fair for Gemstones, Gemstone Jewellery and Gemstone Objects (“Intergem”) has been held in Idar-Oberstein. Some 130 exhibitors present exquisite gemstones in modern and classical cuts, flawless jewellery, artistic engravings, sophisticated chokers with coloured gemstones, uncut gems, the whole gamut of cultured pearls and all that goes with them. The fair takes place at the Jahnhaus in the constituent community of Algenrodt, although as of 2008, a move to the planned exhibition hall in the new Nahetal commercial park (US Army storage depot) was being considered.

The Idar-Obersteiner Wirtschaftstage (“Economy Days”), initiated by the Idar-Oberstein Economic Promotional Association, are regarded in and around Idar-Oberstein as a regional fair.

Natural gemstone deposits

Gemstones from throughout the world are to be found in Idar-Oberstein, but the whole industry was begun by finds in the local area. These include agate, jasper and rock crystal.

Garrison

Since 1938, Idar-Oberstein has been a garrison town. During the 19th and 20th centuries, French and German soldiers in turn were stationed here. With the coming of the Wehrmacht, new barracks were built. After the Second World War, the Straßburgkaserne (“Strasbourg Barracks”) were at first used by the United States Army. French troops were stationed at the Klotzbergkaserne, and then as of 1956, the Bundeswehr artillery school. This moved in the late 1960s to the newly built Rilchenbergkaserne. Since that time, thousands of artillerymen have undergone their basic and advanced military training here. In September 2003, new boarding school buildings and teaching rooms were dedicated so that today’s artillery school has at its disposal both up-to-date lodging capacity and a training centre with all the modern equipment. Included among the teaching methods are audio, video and simulation techniques. Stationed at the Klotzbergkaserne until 31 March 2003 was the Beobachtungspanzerartillerielehrbataillon (“Observational Armoured Artillery Teaching Battalion”) 51, after whose dissolution in the course of Bundeswehr reform, the language training centre for officer cadets moved in. For businesses in Idar-Oberstein and environs, the Bundeswehr is a major economic factor as both an employer and a client. Since 1988, there has been a “sponsorship” between the town of Idar-Oberstein and the artillery school, and to highlight the relationship, town council decided in 1988 to put up a second roadsign that read “Hauptstadt der deutschen Artillerie” (“German Artillery Capital”). After objections from local business, among others the local chamber of commerce, and from some of the townsfolk, too, it was decided that the town would not go to the trouble of installing such signs after all.[15] In 2006, the officer cadet battalion was disbanded.

Transport

Idar-Oberstein’s railway station, as a Regional-Express and Regionalbahn stop, is linked by way of the Nahe Valley Railway (Bingen–Saarbrücken) to the Saarland and the Frankfurt Rhine Main Region. The Rhein-Nahe-Express running the Mainz-Saarbrücken route serves the station hourly. Every other one of these trains goes through to the main railway station in Frankfurt with a stop at Frankfurt Airport. Formerly, fast trains on the Frankfurt-Paris route had a stop at Idar-Oberstein.

Local transport in Idar-Oberstein was run from 1900 to 1956 by trams, and from 1932 to 1969 by trolleybuses. Today’s network is made up of six bus routes run by the Verkehrsgesellschaft Idar-Oberstein GmbH, which belongs to the Rhenus Veniro Group. Furthermore, Idar-Oberstein is the starting point for Regio bus routes to Baumholder and Birkenfeld. There is also a direct bus link to Frankfurt-Hahn Airport. The most important road link in town is Bundesstraße 41; although there is no direct Autobahn link, the A 62 (Kaiserslautern–Trier) can be reached through interchanges at Birkenfeld (B 41) or Freisen.

Highway over the Nahe

In the 1980s, the river Nahe was covered over with a four-lane highway, Bundesstraße 41, mentioned above, putting the river underground, beneath the town. This is unique in Germany and has greatly changed the town’s appearance in this area. The first plans for this development (officially the Nahehochstraße) lay before planners as early as 1958, but they set off a wave of criticism that was felt far beyond the town’s limits. On the theme of “Highway over the Nahe – yes or no”, Südwestfunk broadcast a talk show in the 1980s. The project was meant to relieve traffic congestion in the inner town on the B 41, which at the time ran through what is now a narrow pedestrian precinct through the middle of the Old Town. Work on the project began in 1980, and lasted five years, after which the Nahehochstraße was at last completed. The Nahe had thus been channelled into a two-kilometre-long tunnel. A timber-frame house nearby, the Sachsenhaus, was torn down and put into storage, its pieces numbered. Its reconstruction has been indefinitely postponed. In 1986, the Naheüberbauung, as it is commonly known, was opened to traffic. For its 20th anniversary, there was an exhibition at the Idar-Oberstein Stadthaus (civic centre) with photo galleries about the planning, building and completion of the project.

For its efforts, Idar-Oberstein won an award in 1988 in a contest staged by German town planners: First Prize for Most Consequential Blighting of an Historic Townscape.[16]

I-O/Göttschied Airfield

Idar-Oberstein/Göttschied Airfield lies north of the town between the constituent community of Göttschied and the municipalities of Gerach and Hintertiefenbach at an elevation of 480 m above sea level (1,575 feet). Its ICAO location indicator is EDRG. The grass landing strip’s orientation is 06/24, and it is 650 m long and 50 m wide. The allowable landing weight is 2 000 kg; however, with PPR (“prior permission required”), aircraft of up to 3 700 kg may land. The airport is designed for helicopters, motor gliders, gliders, ultralights and, also with PPR, skydivers.

Offered here on weekends are sightseeing flights by motorized aircraft, motor glider, glider and ultralight.

Media

- Nahe-Zeitung (Rhein-Zeitung, newspaper)

- Wochenspiegel Idar-Oberstein (weekly advertising paper)

- Stadtfacette Idar-Oberstein (newspaper)

- Radio Idar-Oberstein 87.6

- SWR Studio Idar-Oberstein

- FAN (music magazine)

- Idar-Oberstein/Herrstein public-access channel

- Transmission facilities: SWR Nahetal Transmitter, Idar-Oberstein-Hillschied Transmitter

Public institutions

- Klinikum Idar-Oberstein

- The KMT-Klinik is a clinic for bone marrow transplants and haematology.

The University of Mainz specialist and teaching hospital, which grew out of the former Municipal Hospitals, is part of the Saarland Heilstätten (a group of hospitals) – even though it is not in the Saarland – and has some 500 beds and 1,000 employees, as well as departments for general, abdominal and vascular surgery, gynaecology with obstetrics, internal medicine with gastroenterology, nephrology, diabetology and dialysis, diagnostic and interventional radiology, cardiology, bone marrow transplantation and haematology/oncology, neurology with a stroke unit and neurosurgery, psychiatry with child and adolescent psychiatry and psychotherapy, paediatrics with neonatology, radiation therapy, trauma surgery and urology as well as wards for ophthalmology and otorhinolaryngology. Excluded from this is a geriatric rehabilitation clinic in Baumholder. There is also no nursing school.

Education

Idar-Oberstein is home to every kind of educational institution, and since 1986, it has been a Hochschule location. The internationally renowned programme of Gemstone and Jewellery Design of the Faculty of Design at the University of Applied Sciences Trier is the only place in Europe where artistically-scientifically oriented studies in design in the field of gemstones and jewellery can be undertaken. It is found together with the professional school centre and the town’s only Realschule at the Schulzentrum Vollmersbachtal. There are several Hauptschulen throughout the town. There are moreover four Gymnasien: the Göttenbach-Gymnasium and the Gymnasium an der Heinzenwies can be attended beginning at the fifth class, while the Technisches Gymnasium and the Wirtschaftsgymnasium only admit students beginning in the eleventh class.

- The University of Mainz maintains the Institut für Edelsteinforschung (Institute for Gemstone Research) in Idar-Oberstein. The Gemstone Research Department belongs to the subject area of mineralogy in the Faculty of Earth Sciences.

- The University of Applied Sciences Trier offers at its Idar-Oberstein location a programme in Gemstone and Jewellery Design.

- The Deutsche Gemmologische Gesellschaft e. V. (“DGemG”, German Gemological Association) was founded in 1932 and developed into an internationally renowned institution of technical-scientific gemmology. Successful participation in the DGemG courses in gemmology and diamond studies leads to diploma certification of performance on examinations that qualify the graduate to apply for membership in the DGemG (F. G. G. – the F is for the German word Fachmitgliedschaft, or “professional membership”). Thus far, more than 30,000 participants from 75 countries have attended the DGemG programme, which is designed with the demands of the gemstone and jewellery industry in mind.

- The Forschungsinstitut für mineralische und metallische Werkstoffe Edelsteine/Edelmetalle GmbH (FEE; Research Institute for Mineral and Metallic Materials Gemstones/Precious Metals), too, has its seat in Idar-Oberstein. The FEE specializes in growing crystals and manufacturing optical elements for lasers.

- The Deutsche Diamantprüflabor GmbH (DPL; German Diamond Testing Laboratory) has been assessing since 1970 the quality of cut diamonds. As the first laboratory of its kind in Germany (and second in the world), the DPL has been officially certified by the German Testing Accreditation System in Berlin as being able to carry out competent quality assessment of diamonds with regards to colour, size, cut and proportion in accordance with internationally recognized standards.

Sundry

In 1997, a Lufthansa Airbus A319-114 (registration number D-AILN) was christened “Idar-Oberstein”. It came into service on 12 September of that year. The aircraft was for a time leased to the firm Germanwings, but has since been reincorporated into Lufthansa’s fleet.

Famous people

Honorary citizens

- Otto Decker, since 22 December 1947

- Harald Fissler, since 27 January 1995