- Italian Fascism

-

Part of a series on Fascism  Core tenetsNationalism · Totalitarianism · Single party state · Dictatorship · Collectivism · Social Darwinism · Militarism · Mixed economy · Class collaboration · Third PositionTopicsWorksThe Doctrine of Fascism · Fascist manifesto · Mein Kampf · My Autobiography · The Myth of the Twentieth Century · Zaveshchanie russkogo fashistaInternational organizationsHistoryListsRelated topicsAnti-fascism · Clerical fascism · Fascist (epithet) · Glossary of Fascist Italy · Neo-Fascism · Racism · Social fascism · Palingenetic ultranationalism

Core tenetsNationalism · Totalitarianism · Single party state · Dictatorship · Collectivism · Social Darwinism · Militarism · Mixed economy · Class collaboration · Third PositionTopicsWorksThe Doctrine of Fascism · Fascist manifesto · Mein Kampf · My Autobiography · The Myth of the Twentieth Century · Zaveshchanie russkogo fashistaInternational organizationsHistoryListsRelated topicsAnti-fascism · Clerical fascism · Fascist (epithet) · Glossary of Fascist Italy · Neo-Fascism · Racism · Social fascism · Palingenetic ultranationalismFascism portal

Politics portalItalian Fascism also known as Fascism (Italian: Fascismo) with a capital "F" refers to the original fascist ideology in Italy. This ideology is associated with the National Fascist Party which under Benito Mussolini ruled the Kingdom of Italy from 1922 until 1943, the Republican Fascist Party which ruled the Italian Social Republic from 1943 to 1945, the post-war Italian Social Movement, and subsequent Italian neo-fascist movements.

Italian Fascism is based upon Italian nationalism and the restoration of "Italia Irredenta" (claimed unredeemed Italian territories) to Italy and territorial expansionism.[1] Italian Fascists claim that modern Italy is the heir to the Roman Empire and its territorial legacy, and support the creation of "vital space" for colonization by Italian settlers and establishing control over the Mediterranean Sea as Italy's Mare Nostrum as it had been under the Roman Empire.[2]

Italian Fascism promotes a corporatist economic system whereby employer and employee syndicates are linked together in a corporative associations to collectively represent the nation's economic producers and work alongside the state to set national economic policy.[3] Italian Fascists claim that this economic system resolves and ends class conflict by creating class collaboration.[4]

The ideology was founded during World War I by Italian national syndicalists who combined left-wing and right-wing political views, but fascism gravitated to the right in the early 1920s.[5][6] Italian Fascists described fascism as a right-wing ideology in the political program The Doctrine of Fascism: "We are free to believe that this is the century of authority, a century tending to the 'right,' a fascist century."[7][8] However they also officially declared that although they were "sitting on the right" they were generally indifferent to their position on the left-right spectrum, as being a conclusion of their combination of views rather than an objective, and considering it insignificant to their basis of their views that they claimed could just as easily be associated with "the mountain of the center" as with the right.[9]

Etymologically, Fascismo (Fascism) derives from the Italian fascio (league), derived from the Latin fasces (bundles); the ancient Roman Symbol of Authority. It dates from Mussolini’s January 1915 and the 1921 establishment of the National Fascist Party begun as the fasci di combattimento (combat leagues) popular movement.[10][11][12] The English fascism denotes the league connotation of the Italian fascio (fagot); in the Italian language, in denoting the political philosophy, the proper noun Fascismo (Italian pronunciation: [faʃˈʃizmo]) is upper-case, and the generic, common noun fascismo (fascism) is lower-case.

Contents

Doctrine

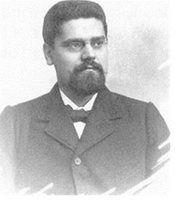

Giovanni Gentile: Philosophic father of Italian Fascism.

Giovanni Gentile: Philosophic father of Italian Fascism.

The Doctrine of Fascism (La dottrina del fascismo, 1932), by the Actualist philosopher Giovanni Gentile, is the official formulation of Italian Fascism, published under Benito Mussolini’s name in 1933.[13] Gentile was intellectually influenced by Hegel, Plato, Benedetto Croce, and Giambattista Vico, as such, his Actual Idealism philosophy was the basis for Fascism.[13] Hence, the Doctrine’s Weltanschauung proposes the world as action in the realm of Humanity — beyond the quotidian constrictions of contemporary political trend, by rejecting “perpetual peace” as fantastical, and accepting Man as a species continually at war; those who meet the challenge, achieve nobility.[13] To wit, Actual Idealism generally accepted that conquerors were the men of historical consequence, e.g. the Roman Julius Caesar, the Greek Alexander the Great, the German Charlemagne, and the French (Corsican) Napoleon; the philosopher–intellectual Gentile was especially inspired by the Roman Empire (27 BC – AD 476, 1453), from whence derives Fascism, thus:[13]

“ The Fascist accepts and loves life; he rejects and despises suicide as cowardly. Life as he understands it means duty, elevation, conquest; life must be lofty and full, it must be lived for oneself but above all for others, both near bye and far off, present and future. ” —Benito Mussolini, The Doctrine of Fascism, 1933.[14]

Therefore, in 1925, Benito Mussolini assumed the title Duce (Leader), derived from the Latin dux (leader), a Roman Republic military-command title. Moreover, although Fascist Italy (1922–43) is historically considered an authoritarian–totalitarian dictatorship, it retained the original “liberal democratic” government façade: the Grand Council of Fascism remained active as administrators; and King Victor Emmanuel III of Italy could — at his Crown’s risk — discretionarily dismiss Mussolini as Italian Prime Minister, as, in the event, he did.[15]

La dottrina del fascismo proposed an Italy of greater living standards under a single-party Fascist system, than under the multi-party liberal democratic government of 1920.[16] As the Leader of the National Fascist Party (PNF — Partito Nazionale Fascista), Benito Mussolini said that democracy is “beautiful in theory; in practice, it is a fallacy”,[17] and spoke of celebrating the burial of the “putrid corpse of liberty”.[16] In 1923, to give Deputy Mussolini control of the pluralist parliamentary government of the Kingdom of Italy (1861–1946), an economist, the Baron Giacomo Acerbo proposed — and the Italian Parliament approved — the Acerbo Law, changing the electoral system from proportional representation to majority representation. The party who received the most votes (provided they possessed at least 25 per cent of cast votes), won two-thirds of the parliament; the remaining third was proportionately shared among the other parties — thus the Fascist manipulation of liberal democratic law that rendered Italy a single-party State.

In 1924, the National Fascist Party won the election with 65 per cent of the votes;[18] yet the United Socialist Party of Italy refused to accept such a defeat — especially Deputy Giacomo Matteotti who, on 30 May 1924, in Parliament formally accused the PNF of electoral fraud, and reiterated his denunciations of PNF Blackshirt political violence, and was publishing The Fascisti Exposed: A Year of Fascist Domination, a book substantiating his accusations.[18][19] Consequently, on 24 June 1924, the Ceka (PNF secret police) assassinated the Parliament Deputy; of the five men arrested, Amerigo Dumini, aka Il Sicario del Duce (The Leader’s Assassin), was sentenced to five years’ imprisonment, yet served only eleven months, and was freed under amnesty from King Victor Emmanuel III. Moreover, when the King supported Prime Minister Mussolini, the socialists cried “Foul!”, and unwisely quit Parliament in protest — leaving the Fascists to govern Italy.[20] In that time, assassination was not yet the modus operandi norm; the Italian Fascist Duce usually disposed of opponents in the Imperial Roman way: political arrest punished with island banishment.[21]

Conditions precipitating Fascism

Nationalist discontent

After the First World War (1914–18), despite the Kingdom of Italy (1861–1946) being a full-partner Allied Power against the Central Powers, Italian nationalism claimed Italy was cheated in the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye (1919), thus the Allies had impeded Italy’s progress to becoming a “Great Power”.[20] Thenceforth, the National Fascist Party (PNF — Partito Nazionale Fascista) successfully exploited that “slight” to Italian nationalism, in presenting Fascism as best-suited for governing the country, by successfully claiming that democracy, socialism, and liberalism were failed systems. The PNF assumed Italian government in 1922, consequent to the Fascist Leader Mussolini’s oratory and Blackshirt paramilitary political violence.

In 1919, at the Paris Peace Conference, the Allies compelled the Kingdom of Italy to yield to Yugoslavia the Croatian seaport of Fiume (Rijeka), a mostly-Italian city of little nationalist significance, until early 1919. Moreover, elsewhere, Italy then was excluded from the wartime secret Treaty of London (1915) it had concorded with the Triple Entente;[22] wherein Italy was to leave the Triple Alliance and join the enemy, by declaring war against the German Empire and Austria-Hungary, in exchange for territories, at war’s end, upon which the Kingdom of Italy held claims. (see Italia irredenta)

In September 1919, the nationalist response of outraged war hero Gabriele d'Annunzio was declaring the establishment of the Italian Regency of Carnaro.[23] To his independent Italian state, he installed himself as the Regent Duce (Leader), and promulgated the Carta del Carnaro (Charter of Carnaro, 8 September 1920 ), a politically-syncretic constitutional amalgamation of right-wing and left-wing anarchist, proto-fascist, and democratic republican politics, which much influenced the politico-philosophic development of early Italian Fascism. Consequent to the Treaty of Rapallo (1920) the metropolitan Italian military deposed the Regency of Duce D’Annunzio on Christmas 1920. In the development of the fascist model of government, Gabriele d’ Annunzio was a nationalist, not a fascist, whose legacy of political–praxis (“Politics as Theatre”) was stylistic (ceremony, uniform, harangue, chanting), not substantive, which Italian Fascism artfully developed as a government model.[23][24]

Labor unrest

Given Italian Fascism’s pragmatic political amalgamations of left-wing and right-wing socio-economic policies, discontented workers and peasants proved an abundant source of popular political power, especially because of peasant opposition to socialist agricultural collectivism. Thus armed, the former socialist Benito Mussolini oratorically inspired and mobilized country and working-class people: “We declare war on socialism, not because it is socialist, but because it has opposed nationalism. . . . ” Moreover, for campaign financing, in the 1920–21 period, the National Fascist Party also courted the industrialists and (historically-feudal) landowners, by appealing to their fears of left-wing socialist and Bolshevik labor politics and urban and rural strikes; the Fascists promised a good business climate of cost-effective labor, wage, and political stability; the Fascist Party was en route to power; the historian Charles F. Delzell reports:

At first, the Fascists [PNF] were concentrated in Milan and a few other cities. They gained ground quite slowly, between 1919 and 1920; not until after the scare, brought about by the workers “occupation of the factories” in the late summer of 1920 did fascism become really widespread. The industrialists began to throw their financial support to it. Moreover, toward the end of 1920, fascism began to spread into the countryside, bidding for the support of large landowners, particularly in the area between Bologna and Ferrara, a traditional stronghold of the Left, and scene of frequent violence. Socialist and Catholic organizer of farm hands in that region, Venezia Giulia, Tuscany, and even distant Apulia, were soon attacked by [Black Shirt] squads of Fascists, armed with castor oil, blackjacks, and more lethal weapons. The era of Squadrismo, and nightly expeditions to burn Socialist and Catholic labor headquarters had begun.

Fascism empowered

The First World War (1914–18) inflated Italy’s economy with great debts, unemployment (aggravated by thousands of demobilised soldiers), social discontent featuring strikes, organised crime,[20] and anarchist, Socialist, and Communist insurrections.[25] When the elected Italian Liberal Party Government could not control Italy, the Fascist Revolutionary Party (FRP) Leader Benito Mussolini took matters in hand, combating those societal ills with the Blackshirts, paramilitary squads of Great War veterans and ex-socialists; Prime Ministers such as Giovanni Giolitti allowed the Fascist’s taking the law in hand.[26] The Liberal Government preferred Fascist class collaboration to the Communist Party of Italy’s bloody class conflict, should they assume government, as had Lenin’s Bolsheviks in the recent Russian Revolution of 1917.[26] The Manifesto of the Fascist Struggle (June 1919) of the FRP presented the politico-philosophic tenets of Fascism; it included women's suffrage, a minimum wage, an eight-hour workday, and reorganisation of public transport.[27] Appeasing its initially strong feminist wing, the Fascist party actually bowed in November 1925, allowing the introduction of limited women's suffrage, much to the dismay of Fascist feminists.[28]

The March on Rome coup d’ État: Mussolini and the PNF paramilitary Blackshirts, October 1922.

The March on Rome coup d’ État: Mussolini and the PNF paramilitary Blackshirts, October 1922.

By the early 1920s, popular support for the Fascist Revolutionary Party’s fight against Bolshevism numbered some 250,000 people. In 1921, the Fascisti (Fascists) metamorphosed into the National Fascist Party, and achieved political legitimacy when Benito Mussolini was elected to the Chamber of Deputies in 1922.[20] Although the Liberal Party retained power, the governing prime ministries proved ephemeral, especially that of the fifth Prime Minister Luigi Facta, whose government proved vacillating.[20] To depose the weak parliamentary democracy, Deputy Mussolini (with military, business, and liberal right-wing support) launched the PNF March on Rome (27–29 October 1922) coup d’État, to oust Prime Minister Facta, and assume the government of Italy, to restore nationalist pride, re-start the economy, increase productivity with labor controls, remove economic business controls, and impose law and order.[20] On 28 October, whilst the “March” occurred, King Victor Emmanuel III withdrew his support of Prime Minister Facta, and appointed PNF Leader Benito Mussolini as the Sixth Prime Minister of Italy. the March on Rome became a victory parade, the Fascists believed their success was revolutionary and traditionalist.[29][30]

Economy

Main article: Economy of Italy under Fascism, 1922–1943Until 1925, when the liberal economist Alberto de Stefani ended his tenure as Minister of Economics (1922–25), after having re-started the economy and balanced the national budget, the Italian Fascist Government’s economic policies were aligned with classical liberalism principles; inheritance, luxury, and foreign capital taxes were abolished;[31] life insurance (1923),[32] and the state communications monopolies were privatised, et cetera. Yet such pro-business enterprise policies apparently did not contradict the State’s financing of banks and industry.

Privatisation — One of Prime Minister Mussolini’s first acts was the 400-million-Lira financing of Gio. Ansaldo & C., one of the country’s most important engineering companies. Subsequent to the 1926 deflation crisis, banks such as the Banco di Roma (Bank of Rome), the Banco di Napoli (Bank of Naples), and the Banco di Sicilia (Bank of Sicily) also were state-financed.[33] In 1924, a private business enterprise established the Unione Radiofonica Italiana (URI — Italian Radiophonic Union), as part of the Marconi group, to which the Italian Fascist Government granted official radio-broadcast monopoly; after the Second World War, URI became the Radio Audizioni Italiane (RAI — Italian Radio Audience, 1954–54), then the Radiotelevisione Italiana (RAI — Italian Radiotelevision).

Agriculture — To strengthen the domestic Italian production of grain, in 1925, the Fascist Government established protectionist policies that ultimately failed (see: the Battle for Grain); historian Denis Mack Smith reports that: “Success in this battle was . . . another illusory propaganda victory, won at the expense of the Italian economy in general, and consumers in particular. . . Those who gained were the owners of the Latifondia, and the propertied classes in general . . . [Mussolini’s] policy conferred a heavy subsidy on the Latifondisti.”[34]

Industry — The Fascist Government countered the Great Depression with public works programs, such as the draining of the Pontine Marshes, hydroelectricity development, railway improvement, and rearmament.[35] In 1933, the Istituto per la Ricostruzione Industriale (IRI — Institute for Industrial Reconstruction) was established to subsidize failing companies, and soon controlled important portions of the national economy via government-linked companies, among them Alfa Romeo. The Italian economy’s Gross National Product increased 2 per cent; automobile production was increased, especially that of the Fiat motor company,[36] and the aeronautical industry was developing.[20] Prime Minister Mussolini also advocated agrarianism as part of the battles for Land, the Lira, and Grain. As Prime Minister, Benito Mussolini physically participated with the workers in doing the work; the “politics as theatre” legacy of Gabriele D’ Anunzio yielded great propaganda images of Il Duce as “Man of the People”.[37][38]

Internal relations

In 1929, as Italian Head of State, Benito Mussolini concluded the unresolved Church–State conflict of the Roman Question (La Questione romana, pending since the Risorgimento, 1815–71) with the Lateran Treaty (February 1929), between the Kingdom of Italy and the Holy See, establishing the Vatican City microstate in Rome. In exchange for diplomatic recognition of the Vatican City and compensated territorial losses, the Fascist Government established Roman Catholic religious education in every education level; the Vatican would diplomatically recognize the Italian Fascist State.[16][39]

Moreover, to render the Italian people cosmopolitan, the Fascist Government applied every cultural artefact — from postage stamps to monumental architecture to sculpture — in making every social class conscious of Italy's cultural heritage, namely the Roman, Mediæval, Renaissance, and Baroque periods, and the Modern age.[40] The Fascist Government combated organised crime and the Mafia with violence and vendetta (honour).[41] Mussolini’s establishment of law and order to Italy and its society was praised by Winston Churchill,[42] Sigmund Freud,[43] George Bernard Shaw,[44] and Thomas Edison.[45]

Nationalism and Empire

Influenced by the Roman Empire, Il Duce, Prime Minister Benito Mussolini, perceived himself as a contemporary Roman Emperor, and set to establishing a new Italian Empire.[46] With an expansionist and militarian agenda, Italian colonialism penetrated Africa in competition with the British and French empires.[47] The first Italian Fascist colony was Eritrea, in East Africa; then Libya, Somalia, and Ethiopia.[47] The Fascists ruled via authoritarian government, especially in combating insurgents and guerrillas attempting to expel the Italians from their colonized countries; Omar Mukhtar was a notable Libyan example.

International Fascism: The Italian Empire in 1939.

International Fascism: The Italian Empire in 1939.

Moreover, Italian Fascism was (officially) neither atheist nor racist — provided the colonized folk agreed to Italianisation and swore fealty to Il Duce, (See: Racial classification).[46] Just as Italian Jews were allowed membership in the National Fascist Party, in metropolitan Italy,[48][49] in the Libyan colony, Muslims were Fascist Party members via the Muslim Association of the Lictor.[50] In a unity ceremony, a Libyan chief awarded Prime Minister Mussolini an ancient Yemeni Sword of Islam artefact.[51] East Africans were allowed to serve with Italians in the MVSN Colonial Militia.[52]

To fulfil Italian unification, Fascist imperialism included the Italia irredenta (Irredentist Italy) demand of Italian ethnic integrity — recovering all lands previously annexed to the states incorporated to Italy.[53] Said revanchism included the County of Nice, part of the Kingdom of Sardinia until 1860, the Duchy of Savoy,[54] Corsica, part of the Republic of Genoa until 1768,[55] Dalmatia, part of the Republic of Venice until 1797, and the island of Malta, part of the Kingdom of Sicily until 1530.[56]

To prepare the Italians for military conquest, Mussolini's agenda became radical in the 1930s; seeking a physically fit and psychologically tough imperialist people to establish a modern Italian Empire, like the Roman Empire, he advocated discarding formalities of language, thought, and action; a coarse mind and hard body suited for aggressive war. The radical social change to Italian society signalled greater ideologic affinity with Nazi Germany in international diplomacy, given Nazi approval of Italian Fascist imperial ambitions. Moreover, whilst in Germany, on 27 January 1938, an impressed Mussolini observed Wehrmacht soldiers march in goose-step. Upon returning to Italy, he adopted that marching style for his military, and also promulgated legal Anti-Semitism in the Manifesto of Race in July 1938, stripping Jews of Italian citizenship and with it any position in the government or previously held professions. The changes were partly unwelcome, because the Italians were not especially hateful of Jews, and thus were wary of such a cultural imposition, because of a strong German Nazi–Italian Fascist relations.[citation needed] Despite parallels between Nazi Germany’s racist domestic and foreign policies with those of Italy, Il Duce Mussolini was inconsistent about the application of racism in society. Despite, in the 1920s, having emphasized the importance of “race”, speaking in racialist terms about white–coloured relations, stating that the races are in continual competition:

“ [When the] city dies, the nation — deprived of the young life, [the] blood of new generations — is now made up of people who are old and degenerate and cannot defend itself against a younger people which launches an attack on the now unguarded frontiers. . . . This will happen, and not just to cities and nations, but on an infinitely greater scale: the whole White race, the Western race can be submerged by other coloured races which are multiplying at a rate unknown in our race. ” —Benito Mussolini, 1928.[57]

Yet in the 1933–34 period, when political tensions between Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany occurred over Austrian independence, PM Mussolini opportunistically contradicted his earlier claims about the importance of race, by dismissing it as insignificant:

“ Race! It is a feeling, not a reality: ninety-five percent, at least, is a feeling. Nothing will ever make me believe that biologically pure races can be shown to exist today. . . . National pride has no need of the delirium of race. ” —Benito Mussolini, 1933.[58]

External influence

The Italian Fascism government model was very influential beyond Italy; in the twenty-one-year intermarium of the First and Second world wars, many political scientists and philosophers sought ideologic inspiration from Italy. Italian Fascism was copied by Adolf Hitler's Nazi Party, the Russian Fascist Organization, the Romanian National Fascist Movement (the National Romanian Fascia, National Italo-Romanian Cultural and Economic Movement), the Dutch fascists based upon the Verbond van Actualisten journal of H. A. Sinclair de Rochemont and Alfred Haighton. The Sammarinese Fascist Party established an early Fascist government in San Marino, their politico-philosophic basis essentially was Italian Fascism.

Switzerland — pro-Nazi Colonel Arthur Fonjallaz of the National Front, became an ardent Mussolini admirer after visiting Italy in 1932. He advocated the Italian annexation of Switzerland, whilst receiving Fascist foreign aid.[59] The country was host for two Italian politico-cultural activities: the International Centre for Fascist Studies (CINEF — Centre International d’ Études Fascistes), and the 1934 congress of the Action Committee for the Universality of Rome (CAUR — Comitato d’ Azione della Università de Roma).[60]

Spain — The writer Ernesto Giménez Caballero, in Genio de España (The Genius of Spain, 1932) called for the Italian annexation of Spain, led by Mussolini presiding an international Latin Roman Catholic empire. He then progressed to close associated with Falangism, leading to discarding the Spanish annexation to Italy.[61]

Italian Fascist mnemonics

Fascist propaganda, 1933: “Book and Musket make the Perfect Fascist, by loving God, the Motherland, and the Family”. After 1929, the Cross of Lorraine and fasces represent the innate connection between Christianity and Fascism. Anno XI E.F. (Year Eleven of the Fascist Elevation).

Fascist propaganda, 1933: “Book and Musket make the Perfect Fascist, by loving God, the Motherland, and the Family”. After 1929, the Cross of Lorraine and fasces represent the innate connection between Christianity and Fascism. Anno XI E.F. (Year Eleven of the Fascist Elevation).

Some Italian Fascism mottoes and slogans that taught the fascist citizen to abide[clarification needed] responsibility to the State[citation needed]:

- Me ne frego (“I don’t give a damn!”): the Italian Fascist motto.

- Libro e moschetto — fascista perfetto (“Book and Musket — Perfect Fascist”)

- Viva la Morte (“Long live Death!”): sacrifice.

- Tutto nello Stato, niente al di fuori dello Stato, nulla contro lo Stato (“Everything in the State, nothing outside the State, nothing against the State”).[62]

- Credere, Obbedire, Combattere (“Believe, Obey, Fight”)

- Se avanzo, seguitemi. Se indietreggio, uccidetemi. Se muoio, vendicatemi (“If I advance, follow me. If I retreat, kill me. If I die, avenge me”) Borrowed from French Royalist Gen. Henri de la Rochejaquelein.

- Viva Il Duce (“Long live the Leader”)

- 'War is to Man as Motherhood is to Woman.[63]

- Boia chi molla (“who abandons the struggle is a hangman/executioner”), leaving the fight is seen as killing your own comrades. "Boia" was commonly used as an insult in Italy for centuries.

- Molti nemici. Molto onore (“Many enemies. Much Honor”)

- E' l'aratro che traccia il solco, ma è la spada che lo difende ("The plough cuts the furrow, but the sword defends it")

See also

History of Italy

This article is part of a seriesAncient history Prehistoric Italy Etruscan civilization (12th–6th c. BC) Magna Graecia (8th–7th c. BC) Ancient Rome (8th c. BC–5th c. AD) Ostrogothic domination (5th–6th c.) Middle Ages Italy in the Middle Ages Byzantine reconquest of Italy (6th–8th c.) Lombard domination (6th–8th c.) Italy in the Carolingian Empire and HRE Islam and Normans in southern Italy Maritime Republics and Italian city-states Early modern period Italian Renaissance (14th–16th c.) Italian Wars (1494–1559) Foreign domination (1559–1814) Italian unification (1815–1861) Modern history Monarchy (1861–1945) Italy in World War I (1914–1918) Fascism and Colonial Empire (1918–1945) Italy in World War II (1940–1945) Republic (1945–present) Years of lead (1970s–1980s) Topics Historical states Military history Economic history Genetic history Citizenship history Fashion history Postal history Railway history Currency history Musical history

Italy Portal

- Fascism

- Definitions of fascism

- Propaganda of Fascist Italy

- Economy of Italy under Fascism, 1922–1943

- National Fascist Party

- Italian fascist states:

- Kingdom of Italy (1861–1946) (1922–1943, as a fascist state)

- Italian Social Republic (1943–1945)

- Cesare Mori

- Model of masculinity under fascist Italy

- Patriot movement

Notes

- ^ Aristotle A. Kallis. Fascist ideology: territory and expansionism in Italy and Germany, 1922-1945. London, England, UK; New York, New York, USA: Routledge, 2000. Pp. 41.

- ^ Aristotle A. Kallis. Fascist ideology: territory and expansionism in Italy and Germany, 1922-1945. London, England, UK; New York, New York, USA: Routledge, 2000. Pp. 50.

- ^ Andrew Vincent. Modern Political Ideologies. Third edition. Malden, Massaschussetts, USA; Oxford, England, UK; West Sussex, England, UK: Blackwell Publishers Ltd., 2010. Pp. 160.

- ^ John Whittam. Fascist Italy. Manchester, England, UK; New York, New York, USA: Manchester University Press, 1995. Pp. 160.

- ^ Sternhell, Zeev, Mario Sznajder and Maia Ashéri, The Birth of Fascist Ideology: From Cultural Rebellion to Political Revolution (Princeton University Press, 1994) p. 161.

- ^ Borsella, Cristogianni and Adolph Caso. Fascist Italy: A Concise Historical Narrative (Wellesley, Massachusetts: Branden Books, 2007) p. 76.

- ^ Schnapp, Jeffrey Thompson, Olivia E. Sears, Maria G. Stampino, A Primer of Italian Fascism (University of Nebraska Press, 2000. p. 57). Quote: "We are free to believe that this is the century of authority, a century tending to the 'right,' a fascist century,"

- ^ Benito Mussolini. Fascism: Dctrine and Institutions. (Rome, Italy: Ardita Publishers, 1935) p. 26. Quote from the Doctrine of Fascism: "We are free to believe that this is the century of authority, a century tending to the 'right,' a fascist century."

- ^ Mussolini quoted in: Gentile, Emilio. The origins of Fascist ideology, 1918-1925. Enigma Books, 2005. p. 205

- ^ Laqueuer, Walter." Comparative Study of Fascism" by Juan J. Linz. Fascism, A Reader's Guide: Analyses, interpretations, Bibliography. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1976. p. 15 "Fascism is above all a nationalist movement and therefore wherever the nation and the state are strongly identified."

- ^ Laqueur, Walter. Fascism: Past, Present, Future. Oxford University Press, 1997. p. 90. "the common belief in nationalism, hierarchical structures, and the leader principle."

- ^ Koln, Hans; Calhoun, Craig. The Idea of Nationalism: A Study in its Origins and Background. Transaction Publishers. Pp 20.

University of California. 1942. Journal of Central European Affairs. Volume 2. - ^ a b c d Gregor, A. James. Giovanni Gentile: Philosopher Of Fascism. Transaction Pub. ISBN 0765805936. http://books.google.com/books?id=xQEjHAAACAAJ&dq=giovanni+gentile.

- ^ "The Doctrine of Fascism - Benito Mussolini (1932)". WorldFutureFund.org. 8 January 2008. http://www.worldfuturefund.org/wffmaster/Reading/Germany/mussolini.htm.

- ^ Moseley, Ray. Mussolini: The Last 600 Days of Il Duce. Taylor Trade. ISBN 1589790952. http://books.google.com/books?id=UmxaWvOL_IgC&pg=PA7&lpg=PA7&dq=Campo+Imperatore+abruzzo+mussolini&source=web&ots=LhKonN8yB9&sig=Z2HGLGJ_ldFqh6r8ElzmuqUs7c4&hl=en.

- ^ a b c Heater, Derek Benjamin. Our World this Century. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0199133247. http://books.google.com/books?id=94oMyEWGnXYC&pg=PA47&dq=Lateran+Treaty+mussolini&sig=ACfU3U22an9Yd029LbC-gI1OMBFsJZ3OHQ.

- ^ Spignesi, Stephen J. The Italian 100: A Ranking of the Most Influential, Cultural, Scientific, and Political Figures,Past and Present. CITADEL PR. ISBN 0806523999. http://books.google.com/books?id=ufXPKUqorS8C&dq=%22Democracy+is+beautiful+in+theory%22.

- ^ a b "So Long Ago". Time.com. 8 January 2008. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,797902,00.html.

- ^ Speech of the 30th of May 1924 the last speech of Matteotti, from it.wikisource

- ^ a b c d e f g "Mussolini and Fascism in Italy". FSmitha.com. 8 January 2008. http://www.fsmitha.com/h2/ch12.htm.

- ^ Farrell, Nicholas Burgess. Mussolini: A New Life. Orion Publishing Group. ISBN 1842121235. http://books.google.com/books?id=aSlIzmsxU8oC&dq=new+life+mussolini.

- ^ The Fascist Experience by Edward R. Tannenbaum, p. 22

- ^ a b Macdonald, Hamish. Mussolini and Italian Fascism. Nelson Thornes. ISBN 0748733868. http://books.google.com/books?id=221W9vKkWrcC&pg=PT16&dq=Gabriele+d%27Annunzio+paris+peace&sig=ACfU3U1BTr2IQkCU7gfZKyLAg2TRbp6a8g.

- ^ Roger Eatwell, Fascism: A History (1995)p. 49

- ^ "March on Rome". Encyclopedia Britannica. 8 January 2008. http://original.britannica.com/eb/article-9083848/March-on-Rome.

- ^ a b De Grand, Alexander J. The Hunchback's Tailor: Giovanni Giolitti and Liberal Italy from the Challenge of Mass Politics to the Rise of Fascism, 1882-1922. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 027596874X. http://books.google.com/books?id=Y5x7hE8hp1UC&printsec=frontcover&dq=Giovanni+Giolitti++mussolini&source=gbs_summary_r&cad=0.

- ^ "Flunking Fascism 101". WND.com. 8 January 2008. http://www.wnd.com/news/article.asp?ARTICLE_ID=39164.

- ^ Kevin Passmore, Women, Gender and Fascism in Europe, p. 16

- ^ Fascist Modernization in Italy: Traditional or Revolutionary. Roland Sarti. 8 January 2008. JSTOR 1852268.

- ^ "Mussolini's Italy". Appstate.edu. 8 January 2008. http://www.appstate.edu/~brantzrw/history3134/mussolini.html.

- ^ Daniel Guérin, Fascism and Big Business Chapter IX, Second section, p.193 in the 1999 Syllepse Editions

- ^ Daniel Guérin Fascism and Big Business, Chapter IX, First section, p.191 in the 1999 Syllepse Editions

- ^ Daniel Guérin, Fascism and Big Business, Chapter IX, Fifth section, p.197 in the 1999 Syllepse Editions

- ^ Denis Mack Smith (1981), Mussolini.

- ^ Warwick Palmer, Alan. Who's Who in World Politics: From 1860 to the Present Day. Routledge. ISBN 0415131618. http://books.google.com/books?id=YdMWTvXhVlUC&pg=PA259&lpg=PA259&dq=mussolini's+achievements&source=web&ots=ZIUrvUaAs2&sig=fkqzJNT_g6GFZIm3ILbn43_HDhI.

- ^ Tolliday, Steven. The Power to Manage?: Employers and Industrial Relations in Comparative. Routledge. ISBN 0415026253. http://books.google.com/books?id=UQGKReSZtWsC&pg=PA205&lpg=PA205&dq=fiat+fascism&source=web&ots=MIJ8JzxuR2&sig=a38wr4u2z6bey5JTxo_VFiz84WA&hl=en&sa=X&oi=book_result&resnum=3&ct=result.

- ^ "Anno 1925". Cronologia.it. 8 January 2008. http://cronologia.leonardo.it/storia/a1925b.htm.

- ^ "The Economy in Fascist Italy". HistoryLearningSite.co.uk. 8 January 2008. http://www.historylearningsite.co.uk/economy_in_fascist_italy.htm.

- ^ Chambers Dictionary of World History (2000), pp. 464–65.

- ^ "Donatello Among the Blackshirts". CornellPress.edu. 8 January 2008. http://www.cornellpress.cornell.edu/cup_detail.taf?ti_id=4199.

- ^ "Mussolini Takes On the Mafia". AmericanMafia.com. 8 January 2008. http://www.americanmafia.com/Feature_Articles_267.html.

- ^ "Top Ten Facts About Mussolini". RonterPening.com. 27 January 2008. http://www.ronterpening.com/extras/league_ex.htm.

- ^ Falasca-Zamponi, Simonetta. Fascist Spectacle: The Aesthetics of Power in Mussolini's Italy. University of California Press. ISBN 0520226771. http://books.google.com/books?id=_vcFQTOsRXgC&pg=PA53&lpg=PA53&dq=%22the+Hero+of+Culture%22+Sigmund+Freud&source=web&ots=vAAFHhS7Ve&sig=j-EwhKibadnYTatZcNJmr5FZCR8&hl=en.

- ^ Matthews Gibbs, Anthony. A Bernard Shaw Chronology. Palgrave. ISBN 0312231636. http://books.google.com/books?id=3x8_4LyMyT4C&dq=George+Bernard+Shaw+mussolini.

- ^ "Pound in Purgatory". Leon Surette. 27 January 2008. http://books.google.com/books?id=My2rlb0bnx0C&pg=PA71&lpg=PA71&dq=%22I+am+no+superman+like+Mussolini%22&source=web&ots=UlaTM7Nm67&sig=YW9AV1oyMNjUgc96AgDvJtup2sM&hl=en.

- ^ a b "Mussolini's Cultural Revolution: Fascist or Nationalist?". jch.sagepub.com. 8 January 2008. http://jch.sagepub.com/cgi/reprint/7/3/115.

- ^ a b Copinger, Stewart. The rise and fall of Western colonialism. F.A.Praeger. http://books.google.com/books?id=8tZBAAAAIAAJ&q=italian+empire+colonial+british+french&dq=italian+empire+colonial+british+french&pgis=1.

- ^ "The Italian Holocaust: The Story of an Assimilated Jewish Community". ACJNA.org. 8 January 2008. http://www.acjna.org/acjna/articles_detail.aspx?id=300.

- ^ Hollander, Ethan J (PDF). Italian Fascism and the Jews. University of California. ISBN 0803946481. http://weber.ucsd.edu/~ejhollan/Haaretz%20-%20Ital%20fascism%20-%20English.PDF.

- ^ Segrè, Claudio G. Italo Balbo a fascist life: a Fascist life. University of California Press. ISBN 0520071999. http://books.google.com/books?id=221W9vKkWrcC&pg=PT16&dq=Gabriele+d%27Annunzio+paris+peace&sig=ACfU3U1BTr2IQkCU7gfZKyLAg2TRbp6a8g.

- ^ Galaty, Michael L. Archaeology under dictatorship. Springer. ISBN 0306485087. http://books.google.com/books?id=E0U104S4msoC&pg=PA85&lpg=PA85&dq=%22sword+of+islam%22+mussolini&source=web&ots=Cx7W7waHJS&sig=M1TRQcmwMppSgWzBLjvlKMM0ZHg&hl=en&sa=X&oi=book_result&resnum=3&ct=result.

- ^ Jowett, Philip S. The Italian Army 1940-45 (2): Africa 1940-43. Nelson Thornes. ISBN 1855328658. http://books.google.com/books?id=vrVJAToL35QC&pg=PT21&dq=MVSN+Colonial+Militia&sig=ACfU3U2bwRPGtfE3pHFM-MQFZTS8VM78MA#PPT21,M1.

- ^ Lowe, CJ. Italian Foreign Policy 1870-1940. Routledge. ISBN 0415265975. http://books.google.com/books?id=5Cfuax6XHF0C&pg=PA11&lpg=PA11&dq=irredentism&source=web&ots=Kg9o1ECiRf&sig=9LHnE17Ryi3BqmFRgGuCgT0sNKc&hl=en.

- ^ "Kingdom of Sardinia". Britannica.com. 8 January 2008. http://www.britannica.com/eb/topic-524132/Sardinia.

- ^ "Pasquale Paoli & Corsican Independence from Genoa". Age-of-the-Sage.org. 8 January 2008. http://www.age-of-the-sage.org/historical/biography/paoli_corsica.html.

- ^ "The Order of Saint John and the Kingdom of Sicily". Regalis.com. 8 January 2008. http://www.regalis.com/malta/maltasicily.htm.

- ^ Griffen, Roger (ed.). Fascism. Oxford University Press, 1995. Pp. 59.

- ^ Montagu, Ashley. Man's Most Dangerous Myth: The Fallacy of Race. Rowman Altamira. ISBN 0803946481. http://books.google.com/books?id=tkHqP3vgYi4C&pg=PA187&lpg=PA187&dq=%22+Nothing+will+ever+make+me+believe+that+biologically+pure+races+can+be+shown+to+exist+today%22&source=web&ots=ao7O_J0vr8&sig=22zZBSKlbcxbrBF1PXP3_PJygj0&hl=en.

- ^ Alan Morris Schom, A Survey of Nazi and Pro-Nazi Groups in Switzerland: 1930-1945 for the Simon Wiesenthal Center

- ^ R. Griffin, The Nature of Fascism, London: Routledge, 1993, p. 129

- ^ Philip Rees, Biographical Dictionary of the Extreme Right Since 1890, p. 148

- ^ Used by Musolini in a speech before the Chamber of Deputies on 26 May 1927, Discorsi del 1927, Milano, Alpes, 1928, p. 157

- ^ Sarti, Roland. 1974. The Ax Within: Italian Fascism in Action, New York: New Viewpoints. p.187.

Further reading

References

- "Labor Charter" (1927–1934)

- Mussolini, Benito. Doctrine of Fascism which was published as part of the entry for fascismo in the Enciclopedia Italiana 1932.

- Sorel, Georges. Reflections on Violence.

General

- De Felice, Renzo Interpretations of Fascism, translated by Brenda Huff Everett, Cambridge ; London : Harvard University Press, 1977 ISBN 0-674-45962-8.

- Eatwell, Roger. 1996. Fascism: A History. New York: Allen Lane.

- Hughes, H. Stuart. 1953. The United States and Italy. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Mises, Ludwig von. 1944. Omnipotent Government: The Rise of the Total State and Total War. Grove City: Libertarian Press.

- Paxton, Robert O. 2004. The Anatomy of Fascism. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, ISBN 1-4000-4094-9

- Payne, Stanley G. 1995. A History of Fascism, 1914-45. Madison, Wisc.: University of Wisconsin Press ISBN 0-299-14874-2

- Reich, Wilhelm. 1970. The Mass Psychology of Fascism. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux.

- Seldes, George. 1935. Sawdust Caesar: The Untold History of Mussolini and Fascism. New York and London: Harper and Brothers.

- Alfred Sohn-Rethel Economy and Class Structure of German Fascism,London, CSE Bks, 1978 ISBN 0-906336-00-7

- Adler, Frank, and Danilo Breschi, eds., Special Issue on Italian Fascism, TELOS 133 (Winter 2005).

Fascist ideology

- De Felice, Renzo Fascism : an informal introduction to its theory and practice, an interview with Michael Ledeen, New Brunswick, N.J. : Transaction Books, 1976 ISBN 0-87855-190-5.

- Fritzsche, Peter. 1990. Rehearsals for Fascism: Populism and Political Mobilization in Weimar Germany. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-505780-5

- Griffin, Roger. 2000. "Revolution from the Right: Fascism," chapter in David Parker (ed.) Revolutions and the Revolutionary Tradition in the West 1560-1991, Routledge, London.

- Laqueur, Walter. 1966. Fascism: Past, Present, Future, New York: Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997.

- Schapiro, J. Salwyn. 1949. Liberalism and The Challenge of Fascism, Social Forces in England and France (1815–1870). New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Laclau, Ernesto. 1977. Politics and Ideology in Marxist Theory: Capitalism, Fascism, Populism. London: NLB/Atlantic Highlands Humanities Press.

- Sternhell, Zeev with Mario Sznajder and Maia Asheri. [1989] 1994. The Birth of Fascist Ideology, From Cultural Rebellion to Political Revolution., Trans. David Maisei. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

International fascism

- Coogan, Kevin. 1999. Dreamer of the Day: Francis Parker Yockey and the Postwar Fascist International. Brooklyn, N.Y.: Autonomedia.

- Griffin, Roger. 1991. The Nature of Fascism. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

- Paxton, Robert O. 2004. The Anatomy of Fascism. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

- Weber, Eugen. [1964] 1985. Varieties of Fascism: Doctrines of Revolution in the Twentieth Century, New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold Company, (Contains chapters on fascist movements in different countries.)

- Wallace, Henry. "The Dangers of American Fascism". The New York Times, Sunday, 9 April 1944.

- Trotsky, Leon. 1944 "Fascism, What it is and how to fight it" Pioneer Publishers (pamphlet)

External links

- Fascism Part I - Understanding Fascism and Anti-Semitism

- The Functions of Fascism a radio lecture by Michael Parenti

- Italian Fascism

Categories:- Fascism

- Italian fascism

- Politics of Italy

- Political movements

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.