- Benedetto Croce

-

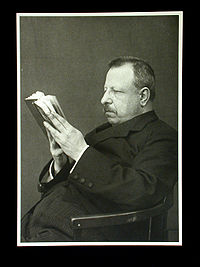

Benedetto Croce

Full name Benedetto Croce Born February 25, 1866

Pescasseroli, ItalyDied November 20, 1952 (aged 86)

Naples, ItalyEra 20th-century Region Western philosophy School Hegelianism, Idealism, Liberalism Main interests History, aesthetics, politics Notable ideas Art is expression Influenced by- Giambattista Vico, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Kant, Fichte, Schelling, G.W.F. Hegel, Karl Marx, Antonio Labriola, Georges Sorel

InfluencedBenedetto Croce (Italian pronunciation: [beneˈdetto ˈkroːtʃe]; February 25, 1866 – November 20, 1952) was an Italian idealist philosopher, and occasionally also politician. He wrote on numerous topics, including philosophy, history, methodology of history writing and aesthetics, and was a prominent liberal, although he opposed laissez-faire free trade. He had considerable influence on other prominent Italian intellectuals including both marxist Antonio Gramsci and fascist Giovanni Gentile.

Contents

Biography

Croce was born in Pescasseroli in the Abruzzo region of Italy. He came from an influential and wealthy family, and was raised in a very strict Catholic environment. Around the age of 16, he turned away from Catholicism and developed a personal view of spiritual life, in which religion cannot be anything but an historical institution where the creative strength of mankind can be expressed. He kept this position for the rest of his life.

In 1883, an earthquake hit the village of Casamicciola, Ischia island, near Naples, where he was on holiday with his family, destroying the home they lived in. His mother, father, and only sister were all killed, while he was buried for a very long time and barely survived. After the incident he inherited his family's fortune and much like Schopenhauer before him was able to live the rest of his life in relative leisure, enabling him to devote a great deal of time to philosophy as an independent intellectual writing from his palazzo in Naples. (Ryn, 2000:xi[1]).

There, he graduated in law at the University of Naples, reading extensively the historic materialism works and news spread at Rome University towards the ends of the 1890s by Professor Antonio Labriola, very much acquainted with and sympathetic to the European socialist thought developments of Filippo Turati, Anna Kuliscioff, Wilhelm Liebknecht, August Bebel, Friedrich Engels, Karl Kautsky and Paul Lafargue.

Under the influence of Neapolitan born Gianbattista Vico's thoughts about art and history he turned to philosophy in 1893. Croce also purchased the house in which Vico had lived. His friend, the philosopher Giovanni Gentile encouraged him to read Hegel. Croce's famous commentary on Hegel, What is Living and What is Dead in the Philosophy of Hegel, appeared in 1907.

As his fame increased, Croce was pushed, against his wishes, to go into politics. He was made Minister of Public Education for a year, and later, in 1910, moved to the Italian Senate, a lifelong position. (Ryn, 2000:xi[1]). He was an open critic of Italy's participation in World War I, feeling that it was a suicidal trade war. Though this made him initially unpopular, his reputation was restored after the war and he became a well-loved public figure. He was also instrumental in the Biblioteca Nazionale Vittorio Emanuele III's move to the Palazzo Reale in 1923.

When the government that made him Minister of Public Education, under Giovanni Giolitti, he was ousted from power by Benito Mussolini, being replaced by the fascist Giovanni Gentile as the new Minister, with whom Croce had earlier cooperated in philosophical polemic against positivism. Though Croce initially supported Mussolini's Fascist government (1922–24),[2] eventually he openly opposed the Fascist Party,[3] while he also distanced himself from his former philosophical partner, Gentile.

Croce was seriously threatened by Mussolini's regime, and his home and library were raided by the fascist troopers. Although he managed to stay outside prison thanks to his status, he was under surveillance, and his academic work was kept in obscurity by the government, to the extent that no mainstream newspaper or academic publication ever referred to him. In 1944, when democracy was restored, Croce, as an "icon of liberal anti-fascism", was again made minister of the new government. (Ryn, 2000:xi-xii[1]). He later left the government and remained president of the Liberal Party until 1947. (Ryn, 2000:xii[1]).

His most interesting philosophical ideas are divided into three works: Aesthetic (1902), Logic (1908), and Philosophy of the practical (1908), but his complete work is spread over 80 books and 40 years worth of publications in his own bimonthly literary magazine, La Critica. (Ryn, 2000:xi[1])

The Philosophy of Spirit

Heavily influenced by Hegel and other German Idealists such as Fichte, Croce produced what was called, by him, the Philosophy of Spirit. His preferred designations were "Absolute Idealism" or "Absolute Historicism". Croce's work can be seen as a second attempt (contra Kant) to resolve the problems and conflicts between empiricism and rationalism (or transcendentalism and sensationalism, respectively). He calls his way immanentism, and concentrates on the lived human experience, as it happens in specific places and times. Since the root of reality is this immanent existence in concrete experience, Croce places aesthetics at the foundation of his philosophy.

The Domains of Mind

Croce's methodological approach to philosophy is expressed in his divisions of the spirit, or mind. He divides mental activity first into the theoretical, and then the practical. The theoretical division splits between aesthetic and logic. This theoretical aesthetic includes most importantly: intuitions and history. The logical includes concepts and relations. Practical spirit is concerned with economics and ethics. Economics is here to be understood as an exhaustive term for all utilitarian matters.

Each of these divisions have an underlying structure that colors, or dictates, the sort of thinking that goes on within them. While Aesthetic is driven by beauty, Logic is subject to truth, Economics is concerned with what is useful, and the moral, or Ethics, is bound to the good. This schema is descriptive in that it attempts to elucidate the logic of human thought; however, it is prescriptive as well, in that these ideas form the basis for epistemological claims and confidence.

History

Croce also held great esteem for Vico, and shared his view that history should be written by philosophers. Croce's On History sets forth the view of history as "philosophy in motion", that there is no greater "cosmic design" or ultimate plan in history, and that the "science of history" was a farce.

Beauty

Croce's work Breviario di estetica (The Essence of Aesthetic) appears in the form of four lessons (quattro lezioni), as he was asked to write and deliver them at the inauguration of Rice University in 1912. He declined the invitation to attend the event; however, he wrote the lessons and submitted them for translation, so that they could be read in his absence.

In this brief, but dense, work, Croce sets forth his theory of art. He claimed that art is more important than science or metaphysics, since only the former edifies us. He felt that all we know can be reduced to logical and imaginative knowledge. Art springs from the latter, making it at its heart, pure imagery. All thought is based in part on this, and it precedes all other thought. The task of an artist is then to put forth the perfect image that they can produce for their viewer, since this is what beauty fundamentally is – the formation of inward, mental images in their ideal state. Our intuition is the basis of forming these concepts within us.

This theory was later heavily debated by such contemporary Italian thinkers as Umberto Eco, who locates the aesthetic within a semiotic construction.[4]

Contributions to liberal political theory

Croce's liberalism is unique when compared to the standard Angloamerican definitions of liberal politics: while Croce theorises that the individual is the centre of society, he rejects social atomism, and while Croce accepts limited government, he refuses that the government should have fixed legitimate powers.

Croce disagrees with John Locke in the nature of liberty, in the sense that he believes that liberty is not a natural right but an earned right that arises out of continuing historical struggle for its maintenance.

Croce defined civilization as the "continual vigilance" against barbarism, and liberty fit into his ideal for civilization as it allows one to experience the full potential of life.

Croce also rejects egalitarianism as absurd. In short, his variety of liberalism is aristocratic, as he views society being led by the few who can create the goodness of truth, civilization, and beauty, with the great mass of citizens simply benefiting from them but unable to fully comprehend their creations. (Ryn, 2000:xii[1]).

Selected quotations

- All history is contemporary history.

Selected bibliography

- Materialismo storico ed economia marxistica (1900).# English edition: Historical Materialism and the Economics of Karl Marx. Whitefish, MT: Kessinger, 2004. See also: http://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/croce/

- L'Estetica come scienza dell'espressione e linguistica generale (1902), commonly referred to as Aesthetic in English.

- Logica come scienza del concetto puro (1909)

- Breviario di estetica (1912)

- Saggio sul Hegel (1907), (1912)# English edition: What is Living and What is Dead in the Philosophy of Hegel, transl. by Douglas Ainslie. London: Macmillan, 1915. See also: http://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/croce/

- Teoria e storia della storiografia (1916). English edition: Theory and history of Historiography, translation by Douglas Ainslie, Editor: George G. Harrap. London (1921).

- Racconto degli racconti (first translation into Italian from Neapolitan of Giambattista Basile's Pentamerone, Lo cunto de li cunti, 1925)

- "Manifesto of the Anti-Fascist Intellectuals" (1 May 1925 in La Critica)

- Ultimi saggi (1935)

- La poesia (1936)

- La storia come pensiero e come azione (meaning History as thought and as action[1]) (1938), translated in English by Sylvia Sprigge as History as the story of liberty in 1941 in London by George Allen & Unwin and in USA by W.W. Norton. The most recent edited translation based on that of Sprigge is Liberty Fund Inc. in 2000. The 1941 English translation is accessible online through Questia.

- Il carattere della filosofia moderna (1941)

- Filosofia e storiografia (1949)

Further reading

- Parente, Alfredo. Il pensiero politico di Benedetto Croce e il nuovo liberalismo (1944).

- Myra E. Moss, Benedetto Croce reconsidered: Truth and Error in Theories of Art, Literature, and History ,(1987). Hanover, NH: UP of New England, 1987.

- Ernesto Paolozzi, Science and Philosophy in Benedetto Croce, in "Rivista di Studi Italiani", University of Toronto, 2002.

- Janos Keleman, A Paradoxical Truth. Croce's Thesis of Contemporary History, in "Rivista di Studi Italiani, University of Toronto, 2002.

- Giuseppe Gembillo, Croce and the Theorists of Complexity, in "Rivista di Studi Italiani, University of Toronto, 2002.

- Fabio Fernando Rizi, Benedetto Croce and Italian Fascism, University of Toronto Press, 2003

- Ernesto Paolozzi, Benedetto Croce, Cassitto, Naples, 1998 (translated by M. Verdicchio (2008) www.ernestopaolozzi.it)

- Carlo Schirru, Per un’analisi interlinguistica d’epoca: Grazia Deledda e contemporanei, Rivista Italiana di Linguistica e di Dialettologia, Fabrizio Serra editore, Pisa-Roma, Anno XI, 2009, pp. 9–32

- Matteo Veronesi, Il critico come artista dall'estetismo agli ermetici. D'Annunzio, Croce, Serra, Luzi e altri, Bologna, Azeta Fastpress, 2006, ISBN 8889982055

- Roberts, David D. Benedetto Croce and the Uses of Historicism. Berkeley: U of California Press, (1987).

- Claes G. Ryn, Will, Imagination and Reason: Babbitt, Croce and the Problem of Reality (1997; 1986).

- R. G. Collingwood, Croce's Philosophy of History in The Hibbert Journal, XIX: 263-278 (1921), collected in Collingwood, Essays on a Philosophy of History (University of Texas 1965) at 3-22.

- Roberts, Jeremy, Benito Mussolini, Twenty-First Century Books, 2005. ISBN 978-0-8225-2648-3.

See also

- Liberalism

- Contributions to liberal theory

Footnotes

- ^ a b c d e f g History as the story of liberty: English translation of Croce's 1938 collection of essays originally in Italian; translation published by Liberty Fun Inc. in the USA in 2000 with a foreword by Claes G. Ryn. ISBN 0-86597-268-0 (hardback).

- ^ Denis Mack Smith, "Benedetto Croce: History and Politics", Journal of Contemporary History Vol 8(1) Jan 1973 pg 47.

- ^ . This can be tracked down to after the assassination of Giacomo Matteotti in June 1924. He coined the term onagrocracy (literally "government by braying asses") to describe the style of rule by the Italian Fascist movement and its leader Benito Mussolini's type of government. It is a disdainful term for misgovernment, a late and satirical addition to Aristotle's famous three: tyranny, oligarchy, and democracy.

- ^ Umberto Eco, "A Theory of Semiotics" (Indiana University Press. 1976)

External links

Categories:- 1866 births

- 1952 deaths

- People from the Province of L'Aquila

- Continental philosophers

- 20th-century Italian philosophers

- Italian anti-fascists

- Italian Liberal Party politicians

- Philosophers of history

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.