- Honey badger

-

"Ratel" redirects here. For other uses, see Ratel (disambiguation).

Honey badger

Temporal range: middle Pliocene – Recent

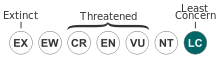

Conservation status Scientific classification Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Class: Mammalia Order: Carnivora Family: Mustelidae Subfamily: Mellivorinae[2] Genus: Mellivora

(Storr, 1780)Species: M. capensis

Geographic distribution The honey badger (Mellivora capensis), also known as the ratel, is a species of mustelid native to Africa, the Middle East and the Indian Subcontinent. Despite its name, the honey badger does not closely resemble other badger species, instead bearing more anatomical similarities to weasels. It is classed as Least Concern by the IUCN due to its extensive range and general environmental adaptations. It is a primarily carnivorous species, and has few natural predators due to its thick skin and ferocious defensive abilities.

Contents

Etymology

Ratel is an Afrikaans word, possibly derived from the Middle Dutch word for rattle, honeycomb (either because of its cry or its taste for honey). In English it is accented on the first syllable, with the "a" pronounced either as in "rate" (/ˈreɪtəl/) or as "father" (/ˈrɑːtəl/).[3]

Taxonomy

Skeleton from the Muséum national d'histoire naturelle

Skeleton from the Muséum national d'histoire naturelle

The honey badger is the only member of the genus Mellivora. Although it was initially assigned to the badger group in the 1860s, it is now generally accepted that they bear very few similarities to the subfamily Melinae, instead being much closer to the marten family. Differences between Mellivora and Melinae include a different dentition. Though not related to the wolverine, which is a large-sized deviant of the marten family, the honey badger can be considered an analogous form of weasel (polecat). The species first appeared during the middle Pliocene in Asia. Its closest relation was the extinct genus Eomellivora, which is known from the upper Miocene, and evolved into several different species throughout the whole Pliocene in both the Old and New World.[4]

Subspecies

As of 2005[update], 12 subspecies are recognised.[5] Points taken into consideration in assigning different subspecies include size and the extent of whiteness or greyness on the back.[6]

Subspecies Trinomial authority Description Range Synonyms Cape ratel

Mellivora capensis capensisSchreber, 1776 South and southwestern Africa mellivorus (G. [Baron] Cuvier, 1798)

ratel (Sparrman, 1777)

typicus (A. Smith, 1833)

vernayi (Roberts, 1932)Ethiopian ratel

Mellivora capensis abyssinicaHollister, 1910 Ethiopia Turkmenian ratel

Mellivora capensis buechneriBaryshnikov, 2000 Similar to the subspecies indica and inaurita, but is distinguished by its larger size and narrower postorbital constriction[7] Turkmenia Lake Chad ratel

Mellivora capensis concisaThomas and Wroughton, 1907 The coat on the back consists largely of very long, pure white bristle-hairs amongst long, fine, black underfur. Its distinguishing feature is the fact that unlike other subspecies, it lacks the usual white bristle-hairs in the lumbar area[8] Sahel and Sudan zones, as far as Somaliland brockmani (Wroughton and Cheesman, 1920)

buchanani (Thomas, 1925)

Black ratel

Mellivora capensis cottoniLydekker, 1906 The fur is typically entirely black, with thin and harsh hairs[8] Ghana, northeastern Congo sagulata (Hollister, 1910) Nepalese ratel

Mellivora capensis inauritaHodgson, 1836 Distinguished from indica by its longer, much woollier coat and having overgrown hair on its heels[9] Nepal and contiguous areas east of it Indian ratel

Mellivora capensis indicaKerr, 1792 Distinguished from capensis by its smaller size, paler fur and having a less distinct lateral white band separating the upper white and lower black areas of the body[10] Western Middle Asia northward to the Ustyurt Plateau and eastward to Amu Darya. Outside the former Soviet Union, its range includes Afghanistan, Iran (except the southwestern part), western Pakistan and western India mellivorus (Bennett, 1830)

ratel (Horsfield, 1851)

ratelus (Fraser, 1862)White-backed ratel

Mellivora capensis leuconotaSclater, 1867 The entire upper side from the face to half-way along the tail is pure creamy white with little admixture of black hairs[8] West Africa, southern Morocco, former French Congo Kenyan ratel

Mellivora capensis maxwelliThomas, 1923 Kenya Arabian ratel

Mellivora capensis pumilioPocock, 1946 Hadhramaut, southern Arabia Speckled ratel

Mellivora capensis signataPocock, 1909 Although its pelage is the normal dense white over the crown, this pale colour starts to thin out over the neck and sholders, continuing to the rump where it fades into black. It possesses an extra lower molar on the left side of the jaw[8] Sierra Leone Persian ratel

Mellivora capensis wilsoniCheesman, 1920 Southwestern Iran and Iraq Physical description

The honey badger has a fairly long body, but is distinctly thick set and broad across the back. Its skin is remarkably loose, and allows it to turn and twist freely within it.[11] The skin around the neck is 6 millimetres (0.24 in) thick, an adaptation to fighting conspecifics.[12] The head is small and flat, with a short muzzle. The eyes are small, and the ears are little more than ridges on the skin,[11] another possible adaptation to avoiding damage while fighting.[12]

The honey badger has short and sturdy legs, with five toes on each foot. The feet are armed with very strong claws, which are short on the hind legs and remarkably long on the forelimbs. It is a partially plantigrade animal whose soles are thickly padded and naked up to the wrists. The tail is short and is covered in long hairs, save for below the base.

Adults measure 23 to 28 centimetres (9.1 to 11 in) in shoulder height and 68–75 cm in body length, with females being smaller than males.[11] Males weigh 12 to 16 kilograms (26 to 35 lb) while females weigh 9.1 kg. Skull length is 13.9–14.5 cm in males and 13 cm for females.[13]

There are two pairs of mammae.[14] The honey badger possesses an anal pouch which, unusually among mustelids, is reversible, a trait shared with hyenas. The smell of the pouch is reportedly "suffocating", and may assist in calming bees when raiding beehives.[15]

The skull bears little similarity to that of the European badger, and greatly resembles a larger version of a marbled polecat skull.[16] The skull is very solidly built, with that of adults having no trace of an independent bone structure. The braincase is broader than that of dogs.

The dental formula is:

. The teeth often display signs of irregular development, with some teeth being exceptionally small, set at unusual angles or are absent altogether. Honey badgers of the subspecies signata have a second lower molar on the left side of their jaw, but not the right. Although it feeds predominantly on soft foods, the honey badger's cheek teeth are often extensively worn. The canine teeth are exceptionally short for carnivores.[17] The tongue has sharp, backward-pointing papillae which assist it in processing tough foods.[18]

. The teeth often display signs of irregular development, with some teeth being exceptionally small, set at unusual angles or are absent altogether. Honey badgers of the subspecies signata have a second lower molar on the left side of their jaw, but not the right. Although it feeds predominantly on soft foods, the honey badger's cheek teeth are often extensively worn. The canine teeth are exceptionally short for carnivores.[17] The tongue has sharp, backward-pointing papillae which assist it in processing tough foods.[18]The winter fur is long (being 40–50 mm long on the lower back), and consists of sparse, coarse, bristle-like hairs lacking underfur. Hairs are even sparser on the flanks, belly and groin. The summer fur is shorter (being only 15 mm long on the back) and even sparser, with the belly being half bare. The sides of the heads and lower body are pure black in colour. A large white band covers their upper bodies, beginning from the top of their heads down to the base of their tails.[19] Honey badgers of the cottoni subspecies are unique in being completely black in colour.[8]

Behavior

Habits

Although mostly solitary, honey badgers may hunt together in pairs during the May breeding season.[18] Little is known of the honey badger's breeding habits. It is thought that its gestation period lasts six months, usually resulting in two cubs, which are born blind. They vocalise through plaintive whines. Their lifespan in the wild is unknown, though captive individuals have been known to live for approximately 24 years.[6]

Honey badgers live alone in self-dug holes. They are skilled diggers, being able to dig tunnels into hard ground in 10 minutes. These burrows usually only have one passage and a nesting chamber and are usually not large, being only 1–3 metres in length. They do not place bedding into the nesting chamber.[20] Although they usually dig their own burrows, they may take over disused aardvark and warthog holes or termite mounds.[18]

Honey badgers are intelligent animals and are one of few species capable of using tools. In the 1997 documentary series Land of the Tiger, a honey badger in India was filmed making use of a tool; the animal rolled a log and stood on it to reach a kingfisher fledgling stuck up in the roots coming from the ceiling in an underground cave.[21]

Honey badgers are notoriously fearless and tough animals, having been known to savagely attack their enemies when escape is impossible. They are tireless in combat and can wear out much larger animals in physical confrontations.[17] The aversion of most predators toward hunting honey badgers has led to the theory that the countershaded coats of cheetah kittens evolved in imitation of the honey badger's colouration in order to ward off predators.[22]

The voice of the honey badger is a hoarse "khrya-ya-ya-ya" sound. When mating, males emit loud grunting sounds.[4] Cubs vocalise through plaintive whines.[6] When attacked by dogs, honey badgers scream like bear cubs.[23]

Diet

Honey badgers have the least specialised diet among mustelids.[12] In undeveloped areas, honey badgers may hunt at any time of the day, though they become nocturnal in places with high human populations. When hunting, honey badgers trot with their fore-toes turned in, moving at the same speed as a young man. Despite their name, honey badgers are primarily carnivorous animals, and will take any sort of animal food at hand, including carrion, small rodents, scorpions, birds, eggs, insects, lizards, snakes, tortoises and frogs. They will eat fruit and vegetables such as berries, roots and bulbs.[18]

They may hunt frogs and rodents such as gerbils and ground squirrels by digging them out of their burrows. Honey badgers are able to feed on tortoises without difficulty, due to their powerful jaws. They kill and eat snakes, even highly venomous or large ones such as cobras. They have been known to dig up human corpses in India.[24] They devour all parts of their prey, including skin, hair, feathers, flesh and bones, holding their food down with their forepaws.[25] When seeking vegetable food, they lift stones or tear bark from trees.[18]

Range

The species ranges through most of Sub-Saharan Africa from the Western Cape, South Africa, to southern Morocco and southwestern Algeria and outside Africa through Arabia, Iran and western Asia to Turkmenistan and the Indian Peninsula. It is known to range from sea level to as much as 2,600 m asl in the Moroccan High Atlas and 4,000 m asl in Ethiopia's Bale Mountains.[1]

Relationships with humans

Honey badgers often become serious poultry predators. Because of their strength and persistence, they are difficult to deter. They are known to rip thick planks from hen-houses or burrow underneath stone foundations. Surplus killing is common during these events, with one incident resulting in the death of 17 Muscovy ducks and 36 pullets.[18]

Because of the toughness and looseness of their skin, honey badgers are very difficult to kill with dogs. Their skin is hard to penetrate, and its looseness allows them to twist and turn on their attackers when held. The only safe grip on a honey badger is on the back of the neck. The skin is also tough enough to resist several machete blows. The only sure way of killing them quickly is through a blow to the skull with a club or a shot to the head with a powerful rifle, as their skin is almost impervious to arrows and spears.[26]

The "Killer badger" is a creature found in a number of modern urban myths from Basra (Al Basrah) province, Iraq, where it was said to have attacked both people and livestock. It has since been identified as the honey badger, inflated by rumour.[27][28][29][30]

In many parts of North India honey badgers are reported to have been living in the close vicinity of human dwellings, leading to many instances of attacks on poultry, small livestock animals and sometimes even children.[citation needed] As they are known to be animals which retaliate fiercely when attacked, ratels are reviled in North India.

In popular culture

A honey badger appears in a running gag in the 1989 film The Gods Must Be Crazy II.[31]

In 2011 a video called "The Crazy Nastyass Honey Badger" became a popular Internet meme, achieving over 20 million views on YouTube as of October 2011.[32] The video features footage from the National Geographic Channel of honey badgers fighting jackals, invading beehives and eating cobras with voiceover by a character named Randall in a vulgar, effeminate, and sometimes exasperated narration, including the popular line that the honey badger "doesn't give a shit".[33] The video has been referenced in an episode of the popular television series Glee and commercials for the video game Madden NFL 12 and Wonderful Pistachios.[34]

LSU Tigers' football player Tyrann Mathieu's nickname is "The Honey Badger". The nickname became popular during the 2011 college football season, when it's often referenced in the national media.[35]

Notes

- ^ a b Begg, K., Begg, C. & Abramov, A. (2008). Mellivora capensis. In: IUCN 2008. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Downloaded on 21 March 2009. Database entry includes a brief justification of why this species is of least concern

- ^ Steve Jackson. "Honey Badger...". http://www.badgers.org.uk/badgerpages/honey-badger-02.html. Retrieved 6 July 2011.

- ^ "ratel, n.2". The Oxford English Dictionary Online. Oxford University Press. March 2009. http://dictionary.oed.com/cgi/entry/50197723. Retrieved 9 November 2010.

- ^ a b Heptner & Sludskii 2002, pp. 1209–1210

- ^ Wozencraft, W. Christopher (16 November 2005). "Order Carnivora (pp. 532-628)". In Wilson, Don E., and Reeder, DeeAnn M., eds. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2 vols. (2142 pp.). p. 612. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494. http://www.bucknell.edu/msw3/browse.asp?id=14001293.

- ^ a b c Rosevear 1974, p. 123

- ^ Baryshnikov G. (2000). "A new subspecies of the honey badger Mellivora capensis from Central Asia". Acta theriologica 45(1): 45–55. abstract.

- ^ a b c d e Rosevear 1974, pp. 126–127

- ^ Pocock 1941, p. 462

- ^ Pocock 1941, p. 458

- ^ a b c Rosevear 1974, p. 113

- ^ a b c Kingdon 1989, p. 87

- ^ Heptner & Sludskii 2002, pp. 1216–1217

- ^ Pocock 1941, p. 456

- ^ Kingdon 1989, p. 89

- ^ Pocock 1941, p. 1214

- ^ a b Rosevear 1974, pp. 114–16

- ^ a b c d e f Rosevear 1974, pp. 117–18

- ^ Heptner & Sludskii 2002, p. 1213

- ^ Heptner & Sludskii 2002, p. 1225

- ^ India Land of the Tiger பாகம் 4 – ஆங்கிலம். Video.google.com. Retrieved on 2011-11-07.

- ^ EATON, R. L. 1976. A possible case of mimicry in larger mammals. Evolution 30:853–856.

- ^ Pocock 1941, p. 465

- ^ Pocock 1941, p. 464

- ^ Rosevear 1974, p. 120

- ^ Rosevear 1974, p. 116

- ^ Weaver, Matthew (2007-07-12), "Basra badger rumour mill", The Guardian

- ^ Philp, Catherine (2007-07-12), Bombs, guns, gangs – now Basra falls prey to the monster badger, The Times

- ^ Baker, Graeme (2007-07-13), British troops blamed for badger plague The Telegraph

- ^ BBC News (2007-07-12) British blamed for Basra badgers, BBC

- ^ Howe, Desson (13 April 1990). "‘The Gods Must Be Crazy II’ (PG)". The Washington Post. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/style/longterm/movies/videos/thegodsmustbecrazyiipghowe_a0b263.htm. Retrieved 22 October 2011.

- ^ The Crazy Nastyass Honey Badger (original narration by Randall). YouTube (2011-01-18). Retrieved on 2011-11-07.

- ^ A Chat With Randall: On Nasty Honey Badgers, Bernie Madoff And Fame. Forbes (2011-04-21). Retrieved on 2011-11-07.

- ^ Jensen, Jeff. (2011-09-30) Honey Badger sure likes pistachios | PopWatch | EW.com. Popwatch.ew.com. Retrieved on 2011-11-07.

- ^ Tyrann Mathieu talks a good game – SEC Blog – ESPN. Espn.go.com. Retrieved on 2011-11-07.

References

- Heptner, V. G.; Sludskii, A. A. (2002). Mammals of the Soviet Union. Vol. II, part 1b, Carnivores (Mustelidae). Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Libraries and National Science Foundation. ISBN 90-04-08876-8. http://ia360707.us.archive.org/18/items/mammalsofsov212001gept/mammalsofsov212001gept.pdf.

- Kingdon, Jonathan (1989). East African mammals, Volume 3 : an atlas of evolution in Africa. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226437213. http://books.google.com/?id=bQjh35ER6ggC&pg=PR7.

- Pocock, R. I. (1941). Fauna of British India: Mammals Volume 2. London: Taylor and Francis. http://ia341313.us.archive.org/0/items/PocockMammalia2/pocock2.pdf.

- Rosevear, Donovan Reginald (1974). The Carnivores of West Africa. London: Trustees of the British Museum (Natural History). ISBN 056500723x. http://ia341037.us.archive.org/1/items/carnivoresofwest00rose/carnivoresofwest00rose.pdf.

External links

- Vanderhaar, Jane M. ; Hwang, Yeen Ten, Mellivora capensis, Published 30 July 2003 by the American Society of Mammalogists

Categories:- IUCN Red List least concern species

- Badgers

- Carnivorans of Africa

- Mammals of Africa

- Mammals of India

- Mammals of Pakistan

- Mammals of Southwest Asia

- Monotypic mammal genera

- Tool-using species

- Animals described in 1776

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.