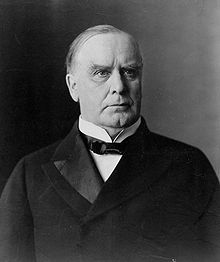

- William McKinley

-

This article is about the 25th President of the United States. For other people with the same name, see William McKinley (disambiguation).

William McKinley

25th President of the United States In office

March 4, 1897 – September 14, 1901Vice President Garret Hobart

Theodore RooseveltPreceded by Grover Cleveland Succeeded by Theodore Roosevelt 39th Governor of Ohio In office

January 11, 1892 – January 13, 1896Lieutenant Andrew Harris Preceded by James Campbell Succeeded by Asa Bushnell Member of the U.S. House of Representatives

from Ohio's 18th districtIn office

March 4, 1887 – March 4, 1891Preceded by Isaac Taylor Succeeded by Joseph Taylor In office

March 4, 1883 – March 4, 1885Preceded by Addison McClure Succeeded by Jonathan Wallace Member of the U.S. House of Representatives

from Ohio's 20th districtIn office

March 4, 1885 – March 4, 1887Preceded by David Paige Succeeded by George Crouse Member of the U.S. House of Representatives

from Ohio's 17th districtIn office

March 4, 1881 – March 4, 1883Preceded by James Monroe Succeeded by Joseph Taylor In office

March 4, 1877 – March 4, 1879Preceded by Laurin Woodworth Succeeded by James Monroe Member of the U.S. House of Representatives

from Ohio's 16th districtIn office

March 4, 1879 – March 4, 1881Preceded by Lorenzo Danford Succeeded by Jonathan Updegraff Personal details Born January 29, 1843

Niles, Ohio, U.S.Died September 14, 1901 (aged 58)

Buffalo, New York, U.S.Political party Republican Spouse(s) Ida Saxton Children Katherine

IdaAlma mater Allegheny College

Albany Law SchoolProfession Lawyer Religion Methodism Signature

Military service Allegiance United States

UnionService/branch United States Army

Union ArmyYears of service 1861–1865 Rank Captain

Brevet majorUnit 23rd Ohio Infantry Battles/wars American Civil War William McKinley, Jr. (January 29, 1843 – September 14, 1901) was the 25th President of the United States (1897–1901). He is best known for winning fiercely fought elections, while supporting the gold standard and high tariffs; he succeeded in forging a Republican coalition that for the most part dominated national politics until the 1930s. He also led the nation to victory in 100 days in the Spanish–American War.

McKinley, a native of Ohio, was of Scots-Irish and English descent, born into a large family, and served with distinction in the Civil War. He became an able lawyer, joined the Ohio Republican party ranks, was married by age 28 and became a father briefly before early suffering the deaths of his two daughters. Wife Ida's health suddenly diminished in 1873 as a result of the proximate deaths of her own mother and a child, and McKinley thereafter assumed an earnest and acclaimed role of caregiving for her, which eventually enabled her to serve as First Lady; it was his need for a diversion from these duties which prompted him to launch his political career.[1]

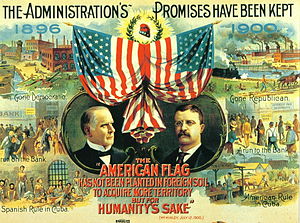

By the late 1870s, McKinley had become a national Republican leader. He served in Congress as Representative of Ohio, and also was elected Governor of Ohio. His signature issue was high tariffs on imports as a formula for prosperity, as typified by his McKinley Tariff of 1890. As the Republican candidate in the 1896 presidential election, opposing Democrat William Jennings Bryan, he promoted pluralism among ethnic groups. His campaign, designed by Mark Hanna, introduced revolutionary advertising techniques, and defeated the crusade of archrival Bryan.

McKinley presided over a return to prosperity after the Panic of 1893, with the gold standard as a keystone. He demanded that Spain end its atrocities in Cuba, which were angering Americans;[2] Spain resisted the interference and the Spanish-American War began in 1898. The U.S. victory was quick and decisive, as the weak Spanish fleets were sunk and both Cuba and the Philippines were captured within a few months. As a result of the 1898 Treaty of Paris, the former Spanish colonies of Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines were annexed by the United States as unincorporated territories, and U.S occupation of Cuba began; this occurred in the face of opposition from Democrats and anti-imperialists who feared a loss of republican values. McKinley also annexed the independent Republic of Hawaii in 1898, with all its inhabitants becoming American citizens.

McKinley was reelected in the 1900 presidential election following another intense campaign against Bryan, which focused on foreign policy and the return of prosperity. President McKinley was assassinated by anarchist Leon Czolgosz in September of the following year in Buffalo, and was succeeded by his Vice President, Theodore Roosevelt. McKinley's presidency receives an aggregate rating of 20th among the presidents in the historical rankings of Presidents of the United States.

Early life and military service

The McKinley clan arrived in Pennsylvania in the 1740s as part of a large migration of Scotch Irish. McKinley's great-grandfather David McKinley, a veteran of the American Revolution, settled in Ohio in the 1790s.[3] David's son James McKinley engaged in the mining and manufacturing of pig iron, as did his son William (the future President's father).[3] William McKinley, Jr., was born in Niles, Ohio, on January 29, 1843, the seventh of nine children. His parents, William Sr. (November 15, 1807 – November 24, 1892) and Nancy (Allison) McKinley (April 22, 1809 – December 12, 1897), were of Scots-Irish and English ancestry.[4] William's siblings included David, James, Anna, Mary, Sarah Elizabeth, Helen, and Abner. One younger sibling died in infancy.[5] When McKinley was ten years old, the family moved to Poland, Ohio.[6] Known as "Wobbly Willie", he graduated from Poland Academy and attended Allegheny College in Pennsylvania for one term in 1860, when he was forced to return home because of illness and was then only able to continue his studies part time while working to pay tuition.[5]

At the start of the American Civil War, he enlisted in the Union Army in June 1861 as a private in the 23rd Ohio Infantry.[7] His superior officer, another future U.S. president, Rutherford B. Hayes, promoted McKinley to commissary sergeant for his bravery in battle while serving the regiment in western Virginia; while not overly ambitious for promotion, McKinley possessed the self respect to request recognition when overdue.[7] Later, for driving a mule team delivering rations under enemy fire at Antietam, Hayes promoted him to first lieutenant.[8] This pattern repeated several times during the war; McKinley eventually made captain, was commissioned a brevet major by Lincoln, and mustered out in September 1865.[8] Hayes is quoted as referring to McKinley as "a handsome, bright, gallant boy and one of the bravest and finest officers in the army."[8] As a result of gallantry demonstrated in his army service in Winchester, Va. he was invited and joined the Masonic lodge there, and eventually rose to become a Knight Templar with the Masons.[9]

Law practice, local politics and marriage

McKinley attended Albany Law School in New York and was admitted to the bar in 1867.[10] That year he decided, with the introduction of his older sister and schoolteacher Anna, to become a resident of Canton, Ohio, and there establish his law practice.[11] He began his practice with a senior judge in Canton who soon thereafter died.[11] That same year he stumped for Hayes as Governor of Ohio and became Chairman of the county Republican committee. McKinley became a local leader of the temperance movement and served as President of the Y.M.C.A.[12] The following year he campaigned for Grant in his presidential bid and was himself elected Stark County prosecutor from 1869 to 1871.[13] His most notable legal case was in June 1876, when 33 striking miners in the employ of the industrialist Mark Hanna were imprisoned for rioting when Hanna brought in strikebreakers to do the work. McKinley defended the miners in court, got all but one of them set free, but refused payment from the group when offered.[14] As a businessman, McKinley has been described by biographer Leech as intelligent and ethical but not financially ambitious.[10]

In 1869 McKinley met and began courting his future wife, Ida Saxton, who was working as a cashier at the bank of her father, James A. Saxton. Ida had graduated from Brooke Hall, predominantly a finishing school. They were married in the local Presbyterian church in January 1871 when she was 23 and he was 27.The following Christmas Day, Ida gave birth to their daughter Katherine.[15] The first two years of their marriage were the happiest of McKinley's life, but proved to be short-lived. In the spring of 1873, Ida was near the delivery of their second child when her mother died, to which she reacted with severe depression. The ensuing delivery of their daughter came only after a very difficult labor, and the child, named Ida, died at five months.[16] Mrs. McKinley began suffering crippling phlebitis and epileptic seizures among other disorders. She became compulsively protective of daughter Katie, who nevertheless also died three years later in 1876.[16]

McKinley responded to his wife's maladies with unprecedented devotion and love. He is said to have practically assumed a second vocation as caretaker for her physical and psychiatric disorders. McKinley became adept at recognizing the onset of seizures and headaches and acting to preserve Ida's comfort and dignity, in all settings, private and public. Inquiring minds were met with tight but discreet lips as to her condition, with not the slightest sign of embarrassment on the part of her spouse.[1] McKinley's constant scrutiny of Ida's condition and needs facilitated her ability to assume and embrace the grandeur required of a governor's wife and First Lady.[1]

U. S. Congressman and Governor of Ohio

With the help of Rutherford Hayes, McKinley was elected as a Republican to the United States House of Representatives for Ohio, first serving from 1877 to 1882, and again from 1885 to 1891. McKinley quickly achieved a strong reputation in the Congress; after just three years he was placed on the powerful Committee on Ways and Means.[17] In the last few days of the 48th Congress he was unseated by Jonathan H. Wallace, a Democrat who successfully contested his narrow election victory, and won on a party vote.[18] McKinley was again elected to the House and served from March 4, 1885, to March 4, 1891. He made a strong impression on party leaders at the 1888 Republican national convention, and that year competed for, but lost, election as Speaker of the House to the more senior Thomas B. Reed. He was however voted Chairman of the Committee on Ways and Means.[19] In 1890, he authored the McKinley Tariff, which raised rates to their highest in history. The political backlash devastated the GOP in the off-year Democratic landslide of 1890. He lost his seat by the narrow margin of 300 votes, partly due to the unpopular tariff bill and partly due to gerrymandering.

McKinley's aggressive promotion of the protective tariff was a by-product of his allegiance to his native rural Ohio, where the economy and livelihoods very much depended upon the production of iron, coal, farm machinery and wool.[20] He became expert at the art of bill drafting, could navigate easily through buried loopholes in the tariff rate schedule, and learned the subtlety of writing a law that appeared to moderate tariff rates while in fact increasing them.[17] But, while McKinley was one-sided on the tariff issue, he most often sought the most practical of solutions to the nation's, and his district's, problems. Rep. Robert La Follette of Wisconsin, who served with him on the Ways and Means Committee, said of him: "Of course McKinley was a high protectionist, but on the great new questions as they arose he was generally on the side of the public against private interests."[21]

After leaving Congress, McKinley ran for and was elected Governor of Ohio in 1891, defeating Democrat James E. Campbell, with the help of Mark Hanna. His campaign emphasized the use of the gold standard, though he later was a proponent of bimetallism, which led to shifts of emphasis and inconsistent statements, resulting in an image of expediency on currency issues.[22] He was reelected in 1893 when opposed by Lawrence T. Neal. As governor, he took a keen interest in industrial arbitration legislation which provided a non mandatory process for the peaceful settlement of labor disputes, and aided in facilitating a few settlements with McKinley's support.[23] In one strike against a railroad, however, he was required to call out the national guard, which quickly restored peace.[24] At the Republican national convention in 1892, he received a few votes as nominee for president while campaigning for the reelection of President Benjamin Harrison, and established himself as a probable candidate for president in 1896.[25]

In 1893, McKinley came close to declaring bankruptcy due to his liability on loans he had endorsed for Robert L. Walker. McKinley had made his endorsements on blank notes, which Walker increased as needed, eventually totaling over $130,000. Due to the fundraising efforts of Hanna on behalf of the victimized, though negligent, McKinley, the obligations were satisfied, bankruptcy (and resignation as Governor) was avoided, and McKinley was able to quickly regain his political poise.[26]

The off-year elections of 1894 found McKinley in very high demand, and had him traversing sixteen states to make over 350 speeches on behalf of various Republicans. He succeeded in bolstering various factions, including farmers, industrialists and union members. Due in part to his efforts, the Democratic majority in the House of Representatives was reversed.[27]

In 1895, a community of severely impoverished miners in Hocking Valley telegraphed Governor McKinley to report their plight, writing, "Immediate relief needed." Within five hours McKinley had paid out of his own pocket for a railroad car full of food and other supplies to be sent to the miners. He then proceeded to contact the Chambers of Commerce in every major city in the state, instructing them to investigate the number of citizens living below poverty level. When reports returned revealing large numbers of starving Ohioans, the governor headed a charity drive and raised enough money to feed, clothe, and supply more than 10,000 people.

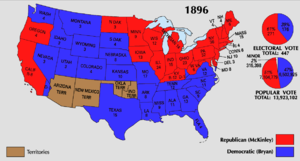

1896 presidential election

Governor McKinley left office in early 1896 and, on the recommendation of his friend and campaign manager Mark Hanna, began actively campaigning for the Republican party's presidential nomination. After sweeping the 1894 congressional elections, Republican prospects appeared bright at the start of 1896. The Democratic Party was split on the issue of silver and many voters blamed the nation's economic woes on incumbent Grover Cleveland. McKinley's well-known expertise on the tariff issue, his successful record as governor, and genial personality appealed to many Republican voters. His major opponent for the nomination, House Speaker Thomas B. Reed of Maine, had acquired too many enemies within the party over his political career and his supporters could not compete with Hanna's organization on behalf of McKinley, who thereby won the nomination on the first ballot; Garret A. Hobart received the nomination as Vice-President.[28] Biographer Leech observed that Hanna and McKinley complemented each other very well, the former being the practical businessman, unclouded by idealistic thinking, the clever organizer and fund raiser, while the latter was the zealous party protagonist, inspiring speaker and diplomat.[29]

After winning the nomination he went home and conducted his campaign exclusively from his front porch, addressing hundreds of thousands of voters, including organizations ranging from traveling salesmen to bicycle clubs. Many of these voters campaigned for McKinley after returning home. McKinley left Canton only twice during the campaign, and his home town took on quite a carnival atmosphere.[30] The Republican National Committee raised an unprecedented $3.5 million.[31]

McKinley's opponent was William Jennings Bryan, who ran on a single issue of "free silver" and money policy. In his letter formally accepting his nomination, McKinley issued a dissertation on the currency question of primary concern, saying "Good money never made times hard", and his remarks eminently satisfied the sound money men, from goldbugs to bimetallists, and also made clear his support of tariffs.[32] McKinley promised that he would promote industry and banking, and guarantee prosperity for every group in a pluralistic nation. A Democratic cartoon ridiculed the promise, saying it would rock the boat. McKinley replied that the protective tariff would bring prosperity to all groups, city and country alike, while Bryan's free silver would create inflation but no new jobs, would bankrupt railroads, and would permanently damage the economy.

McKinley succeeded in getting votes from the urban areas and ethnic labor groups. Campaign manager Hanna adopted new advertising techniques to spread McKinley's message.[33] Although Bryan was ahead in August, McKinley's counter-crusade put him on the defensive and gigantic parades for McKinley in every major city a few days before the election undercut Bryan's allegations that workers were coerced to vote for McKinley. He defeated Bryan by a large margin. His appeal to all classes is thought by many to have marked a realignment of American politics and initiated the progressive era. His success in industrial cities gave the Republican party a grip on the North comparable to that of the Democrats in the South.

Presidency 1897–1901

Domestic policies

McKinley, then aged 54, became the nation's chief executive at a salary of $50,000. The family became regular attendees at the Metropolitan Methodist Church and Mrs. McKinley appeared quite ready and able, with some assistance, to assume her duties as the White House hostess.[34] When he had initially filled all of his cabinet positions, all but two were over the age of 60, and only three would continue in office for more than two years.[35] His inauguration marked the beginning of the greatest consolidation in American business that had ever been seen.[36] The administration did not aggressively enforce the Sherman Antitrust Act, as Theodore Roosevelt later would, and therefore business trusts were allowed to expand.

McKinley's claim as the "advance agent of prosperity" was confirmed when 1897 brought a revival of business, agriculture, and general prosperity, ending the Panic of 1893 which dated back to the Civil War and was marked by persistent underconsumption.[37] The end of the deflationary period resulted largely from a gradual adoption of gold, culminating in passage of the Gold Standard Act of 1900, which set the value of the dollar and alleviated monetary concerns that had plagued the United States since the 1870s.[38] This wave of prosperity, bolstered by US victory in the Spanish-American War, continued into the 20th century until the Panic of 1907, and ensured McKinley's reelection in 1900.

In civil service administration, McKinley reformed the system to make it more flexible in critical areas. The Republican platform, adopted after President Cleveland's extension of the merit system, emphatically endorsed this, as did McKinley himself. Against extreme pressure, particularly in the Department of War, the President resisted until May 29, 1899. His order of that date withdrew from the classified service 4,000 or more positions, removed 3,500 from the class theretofore filled through competitive examination or an orderly practice of promotion, and placed 6,416 more under a system drafted by the Secretary of War. The order declared as permanent a large number of temporary appointments made without examination, including thousands who had served during the Spanish War. In the way of patronage, McKinley adeptly employed appointments to cultivate the favor of members of the Senate, but also made appointments which flowed to his singular benefit. While many suspected otherwise, newly appointed Senator Mark Hanna was not allowed to assume an insider's role in McKinley's appointments.[39] The President had earlier offered Hanna the patronage-dispensing position of Postmaster General, which Hanna refused.

Republicans pointed to the deficit under the Wilson Law of 1894, which had reduced the McKinley tariff, with much the same concern manifested by President Grover Cleveland in 1888 over the surplus. A new tariff law had to be passed, if possible before a new Congressional election. An extra session of Congress was therefore summoned for March 15, 1897. The Ways and Means Committee reported through Chairman Nelson Dingley the bill which bore his name, the House passed the bill and it reached the Senate the last day of March. The Senate passed the bill after toning up its schedules with some 870 amendments, most of which pleased the Conference Committee and it became law. The President signed the act July 24, 1897. The Dingley Act was estimated by its author to advance the average rate from the 40 percent of the Wilson Bill to approximately 50 percent or a shade higher than the McKinley rate. As proportioned to consumption the tax imposed by, it was probably heavier than that under either of its predecessors.

Reciprocity, a feature of the McKinley Tariff, had been suspended by the Wilson Act. The Republican platform of 1896 declared protection and reciprocity twin measures of Republican policy. Clauses graced the Dingley Act allowing reciprocity treaties to be made, "duly ratified" by the Senate and "approved" by Congress. Under the third section of the Act some concessions were given and received, but the treaties negotiated under the fourth section, which involved lowering of strictly protective duties, met summary defeat when submitted to the Senate.

George B. Cortelyou served as the first presidential press secretary of sorts. He was the first individual in the president's office who regularly called for correspondents when an announcement was to be made, provided them with workspace in the White House, and also prepared and distributed statements to the press.[40]

Civil rights

As part of a Methodist family, McKinley was raised an abolitionist by his mother in Poland, Ohio. He was sympathetic to African Americans who struggled under the "Jim Crow" system of second class citizenship in the South. McKinley did not try to reverse Jim Crow (which had won Supreme Court approval in 1896)[41], but he did name some blacks to federal office in the South, including George B. Jackson, a former slave (to the post of customs collector in Presidio) and Walter L. Cohen of New Orleans, a leader of the Black and Tan Republican faction, as a customs inspector.[42]

McKinley made several speeches on African American equality and justice:

“ It must not be equality and justice in the written law only. It must be equality and justice in the law's administration everywhere, and alike administered in every part of the Republic to every citizen thereof. It must not be the cold formality of constitutional enactment. It must be a living birthright.[43] ” “ Our black allies must neither be forsaken nor deserted. I weigh my words. This is the great question not only of the present, but is the great question of the future; and this question will never be settled until it is settled upon principles of justice, recognizing the sanctity of the Constitution of the United States.[43] ” “ Nothing can be permanently settled until the right of every citizen to participate equally in our State and National affairs is unalterably fixed. Tariff, finance, civil service, and all other political and party questions should remain open and unsettled until every citizen who has a constitutional right to share in the determination is free to enjoy it.[43] ” Despite McKinley's laudatory rhetoric, the political realities prevented any real action on the part of his administration in regards to race relations. McKinley did little to alleviate the backwards situation of black Americans because he was "unwilling to alienate the white South."[38] During the Spanish-American War, McKinley made certain that black soldiers served, and even countermanded army orders preventing recruitment of African-American soldiers. Such efforts, as Gerald Bahles points out, however, did little to "stem the deteriorating position of blacks in American society."[38]

Foreign policies

McKinley strove to advance the interests of American producers in world markets, and so his administration promoted the opening of foreign markets, especially in China. While serving as a Congressman, McKinley supported annexation of Hawaii because he wanted to Americanize it and establish a naval base, but Senate resistance previously proved insurmountable as domestic sugar producers and committed anti-expansionists blocked any action. One notable observer of the time, Henry Adams, declared that the nation at this time was ruled by "McKinleyism", a "system of combinations, consolidations, and trusts realized at home and abroad." Although many of his diplomatic appointments went to political friends such as former Carnegie Steel president John George Alexander Leishman (minister to Switzerland and Turkey), professional diplomats such as Andrew Dickson White, John W. Foster, and John Hay also capably served. John Bassett Moore, the nation's leading scholar of international law, frequently advised the administration on the technical legal issues in its foreign relations.

Discussions of the possible annexation of Hawaii by the United States began during the Harrison administration, but had been tabled by Grover Cleveland. McKinley immediately reopened negotiations and on June 16, 1897, an annex treaty was signed.[44] The Government of Hawaii speedily ratified this, and the Japanese protested it, but it lacked the necessary two-thirds vote in the U.S. Senate. The solution was to annex Hawaii by joint resolution. The resolution provided for the assumption by the United States of the Hawaiian debt up to $4,000,000. The Chinese Exclusion Act (1882) was extended to the islands, and Chinese immigration from Hawaii to the mainland was prohibited. The joint resolution passed on July 6, 1898, a majority of the Democrats with several Republicans, among these Speaker Reed, opposing. Shelby M. Cullom, John T. Morgan, Robert R. Hitt, Sanford B. Dole, and Walter F. Frear, made commissioners by its authority, drafted a territorial form of government, which became law April 30, 1900.

The President's selection of leadership in the State Department was a mélange. First, McKinley's appointment of aging Ohio Senator John Sherman to head the State Department was questioned from the outset. While McKinley genuinely hoped Sherman's reputation and experience would bolster the integrity of his Cabinet, it quickly became apparent that Sherman was too old to function in his role.[45] (McKinley's first choice for the State Department, Senator William Allison of Iowa, declined the offer.) Sherman, who previously served as Secretary of the Treasury, initially appeared to be a strong selection. Although Sherman was indeed an experienced statesman, he was too advanced in years, but succeeded for a time in obscuring his increased senility. McKinley named longtime friend William Rufus Day as First Assistant to Sherman, to serve as the de-facto department head, even though Day lacked any experience as a diplomat, and demonstrated it.[45] McKinley further relied on the deaf career diplomat, Alvey A. Adee, as Second Assistant to Sherman, to mentor Day in his role. This lineup was thus often maligned: "The Secretary knows nothing, the First Assistant says nothing, and the Second Assistant hears nothing."[45]

Spanish-American War

The seminal endeavor of McKinley's presidency was the Spanish-American War. The conflict between the two countries stemmed from Spanish atrocities in Cuba, spearheaded by Governor General Weyler in attempts to curb a rebellion by the people.[46] The Spanish repeatedly promised, and then postponed new reforms. Some historians believe that Democrats and the sensationalist yellow journalism of William Randolph Hearst's newspapers were primarily responsible for the American public opinion against Spain, but according to biographer Leech, the newspapers did not create the frenzy, but solidified the public belief that intervention was required based on the situation in Cuba.[46] McKinley and the business community, as well as House Speaker Reed, did not share the public's preference for war.[47][48] While McKinley understood the public's anger toward Spanish atrocities, he was slow in engaging the Spanish, initially by delay in getting his minister to Spain, General Stewart L. Woodford, to assume the post.[46] Spain's new Premier, Praxedas Mateo Sagasta, then replaced General Weyler with Gen. Ramon y Arenas in Cuba to allay the fear of continued atrocities, allowed the U.S. to send food and medicine to Cuba, and all U.S. citizens held in Cuba were released. In the wake of these actions, McKinley asked the country to exercise patience.[49]

Nevertheless, to demonstrate continued American resolve for immediate reform, a warship, the U.S.S. Maine, was dispatched to Havana harbor and placed on call for the U.S. consul general Fitzhugh Lee, to be later joined by the Montgomery.[50] The Department of the Navy, led by Secretary John D, Long, was to be more directly envolved in the Cuban problems than any other department, except for State. Long, recently well recovered from a nervous breakdown, was an ambitious member of the cabinet, while also yearning for the peace and quiet of his farm at home. With the rank of admiral having lapsed, this civilian boss dealt directly with line officers in running the department. Notably at his right hand was a younger, irrepressible and energetic Assistant Secretary, Theodore Roosevelt, anxious to modernize and enlarge the fleet.[51] Long initially succeeded in reining in his junior, at least as concerned increasing the fleet – one additional battleship and accompanying torpedo boats were approved in the Pacific.[52]

On February 15, 1898, the Maine mysteriously exploded and sank in the Havanna harbor, causing the deaths of 250 men, along with a hew and cry from the public for war against Spain; at the same time the State Dept. began intense efforts at negotiations with Spain. The Navy named a board of inquiry to investigate, and McKinley asked the public to withhold judgment until the inquiry, as well as diplomatic negotiations, were complete.[53] The President received a report of the investigation on a Friday, which concluded the explosion was caused by a submarine mine of unknown origin. McKinley immediately prepared a message for Congress, which included a key request for its "deliberate consideration" as well as forbearance while negotiations for peace continued. A copy of the report was leaked that weekend, and significant Congressional and public support for war was emboldened.[54] The President's message was then delayed by another 5 days, to allow for military preparations and evacuation of American citizens from Cuba.[55]

When the President finalized his message to Congress, he softened his stance of preference for negotiation, in favor of a policy of "neutral intervention".[56] Congress initially passed a joint resolution, recognizing Cuban independence (but not a free standing republic), demanding Spanish withdrawal from Cuba, and directing the President to use armed forces for enforcement.[57] The Maine tragedy also led to a sudden realization of naval ill-preparedness, and Congress quickly passed an appropriation bill for $50 million for defense.[58] The onus of Navy purchases fell to Assistant Secretary Roosevelt, who burned to launch the Atlantic Squadron full tilt against Havanna, and who viewed the more sanguine McKinley as "having no more backbone than a chocolate éclair."[58] Nevertheless, Mckinley had promptly issued an ultimatum to Spain to cease and desist, and also ordered a blockade of Cuba.[59] A few days later Congress voted to declare war against Spain, effective with the blockade.[60]

A week after the President's ultimatum, the Navy Department pressed for authority to immediately begin offensives against the Spanish fleet in the Philippines, in light of Britain's declared neutrality and presence in the area. The President responded with authorization to Asiatic Squadron commander George Dewey.[60] Dewey's victory in the Philippines was quick and decisive, and the President promoted him to Rear Admiral for his efforts.[61] McKinley assigned Major General Wesley Merritt the role of military governor in the Philippines, with orders to establish military rule, but to avoid severity upon civilians, and to disown any intent to make war or to ally with any faction.[62] Merritt's mission temporarily stalled in California, for lack of personnel and transportation.[63]

Expeditious victory despite missteps

At the outset of the war, in many respects the War Department was thus not well prepared, under the leadership of Secretary Russell A. Alger. McKinley was also forced to suspend his initial order for an attack on Havana, due to inadequate supplies and troops to proceed. Alger placed unsupported blame on the President for restricting expenditures to coastline defenses.[64] The Navy Department as well was not without its own difficulties in its initial offensive operations in the Caribbean. While the Spanish naval commander Pascual Cervera idled in port at Santiago, U.S. commander Winfield Scott Schley refused to carry out orders to pursue the Spanish fleet, claiming a shortage of coal. Shley also refused to recognize rival William T. Sampson as the top commander in the Cuba operation.[65]

It was only after multiple false starts and chaotic supply management and transportation problems that the Army succeeded in dispatching 17,000 troops (the largest force in U.S. history at the time) from Tampa en route to Santiago under the leadership of William R. Shafter.[66] Once in transit, Shafter consistently directed the campaign of the ground war with minimal consultation or even communication with Sampson and the Navy, shunning use of the marines or the benefit of Naval bombardment.[67] By his own admission, Shafter commented, "there was no strategy about it – just to do it quick."[68] Once unloaded, the troops' orders were first and foremost to move rapidly on Las Gasimas; the offensive was a success, except for the fact that due to continued inefficiencies in the Quartermaster Corps., Shafter had outrun his supplies.[69]

The President was very much aware of the inefficiencies of waging war, and worked mightily to reduce the problems; nevertheless, he had witnessed first hand much worse, in fresh memories of the Civil War. There was a fair amount of finger pointing inherent in the midst of military missteps; McKinley was reluctant to react precipitously, assuming that some of these problems would be experienced regardless of who was in place. Nevertheless, he was quick to point out shortcomings when frustrated, as when Shafter delayed in finishing the campaign in Santiago, when he said to Shafter, "What you went to Santiago for was the Spanish army. If you allow it to evacuate with its arms you must meet it somewhere else. This is not war."[70] While the war was still in its infancy though, McKinley had already begun to focus on the terms of peace, saying, "We must be certain to keep what we have worked to acquire."[71] The President did ultimately ask for Secretary Alger's resignation in the wake of the War Department's many inefficiencies; many thought the action came later than warranted.[72]

Volunteer militia and national guard units indeed rushed to the colors, including Roosevelt and his "Rough Riders".[73] The famous Battle of Las Gisamas and Battle of San Juan Hill were pivotal successes in the war effort, though they came at an inordinate number of casualties equal to ten percent of Shafter's forces.[74] The naval war in Cuba was ultimately also a success, the shortest war in U.S. history. Secretary of State John Hay called it a "splendid little war."

Peace, annexation and criticism of the War Department

McKinley's main conditions for peace in negotiating with the Spanish were 1) relinquishment of Spanish sovereignty over Cuba; 2) cession of Porto Rico and other islands in the West Indies; and 3) relinquishment of the Philippines including Manila and additional territory.[75] At the Peace Conference, which grew out of an initial armistice agreement, Spain sold its rights to the Philippines to the U.S., which took control of the islands and suppressed local rebellions, over the objection of the Democrats and the newly formed Anti-Imperialist League.The President included three senators on the U.S negotiating team so as to facilitate ratification of the resulting treaty.[76] He made the following statement on the negotiations: "We took up arms...in the fulfillment of high public and moral obligations. We had no...ambition of conquest. The United States in making peace should follow the same high rule of conduct...and not ulterior designs which might tempt us into excessive demands."[77] Ratification was assured after conflict erupted on the island of Luzon so as to allow the administration to respond to the emergency there.[78]

McKinley sent William Howard Taft to the Philippines and then to Rome to settle the long-standing dispute over lands owned by the Catholic Church. By 1901 the Philippines were peaceful again after a decade of turmoil.[79] The United States also gained possession of Guam and Puerto Rico from Spain, and political and economic control over Cuba through the Platt Amendment.[80] According to many historians, the United States had thus begun to display attributes of strong imperialism.[81] Hawaii, which for years had tried to join the U.S., was annexed.[79]

In the wake of the combat in Cuba came a scandal over the evacuation of ill and injured troops on two private ships, the Seneca and the Concho, chartered by the Army. Allegations included severe overcrowding on board as well as profiteering in the chartering arrangements. Secretary Alger was said to have acted as an intermediary on behalf of the charter companies which resulted in the premature conclusion of the investigation ordered by the President.[82] Indeed, the rapid victory could not overshadow many areas of mismanagement found in the War Department, including supply management problems by the Quartermaster, food poisoning found throughout the Commissary, and incompetence within the Medical Corps.[83] By the time of the mid-term elections, the President was under pressure from the press, emboldened by public comments critical of the Army from General Nelson Miles; McKinley formed a commission, lead by Granville M. Dodge, to investigate the various issues within the War Department.[84] Miles' testimony was discounted as politically motivated, and the final report of the commission, viewed with considerable skepticism, found deplorable lapses in war preparations but no corruption.[85]

There is a disputed recollection by one person who said McKinley told him in 1899," ... one night it came to me this way...(1) That we could not give them [the Philippines] back to Spain – that would be cowardly and dishonorable; (2) that we could not turn them over to France or Germany – our commercial rivals in the Orient – that would be bad business and discreditable; (3) that we could not leave them to themselves – they were unfit for self-government – and they would soon have anarchy and misrule over there worse than Spain's was; and (4) that there was nothing left for us to do but to take them all, and to educate the Filipinos, and uplift and civilize and Christianize them."[86] The above recollection is not corroborated, according to biographer Gould, who rejects the quotation as unlikely to have been made.[87]

Historians Schweikart and Allen indicate that the "Christianize" point represented a minor factor in the President's policy, though Protestant American missionaries had a presence on the islands. Other historians have dismissed the missionary element as an excuse for sheer secular expansionism.[88] Leech points out that the Fillipinos represented the largest group of Catholics in the Far East.[89] McKinley's policy in favor of annexation was in large part based on the inability of the U.S. to defend the various islands from a limited position in Manila. Great Britain was in favor of the policy and Spain was financially unable to sustain the islands. Annexation was a difficult position for the President, as he had previously denounced "the greed of conquest" and "the criminal aggression of annexation".[90]

Election of 1900 and second term

The President was nominated by his party with Theodore Roosevelt as his running mate. He was publicly silent on the V.P. choice, but privately preferred Sen. William B. Allison, the "father of the Senate" as the V.P. nominee, who declined the offer; McKinley thought Roosevelt should head the War Department.[91] He was re-elected in 1900, this time with economic prosperity in hand and an ebullient national mood after the successful war. Foreign policy was the paramount issue, with the Democrats denouncing the colonialism of the Republicans and insisting the Constitution should follow the flag to annexed territories.[92] William Jennings Bryan, again the Democratic candidate, also reprised the silver issue. McKinley easily won re-election, giving Republicans the largest electoral margin since 1872.[93][94]

All of McKinley's cabinet at the time of the election continued in service with the exception of the Attorney General.[95] In early 1901 the President pressed for settlement of the constitutional and governmental questions in Cuba so that the focus could be turned to the Philippines. He also lead negotiations with Congress on the Spooner bill authorizing establishment of a civil government in the Philippines.[96] Taft was made provisional governor there to demonstrate the nation's resolve to emphasize civil versus military solutions.[97]

The President and Mrs. McKinley took a trip west to California in May 1901. She became quite ill on the trip, and McKinley spent most of his time with his wife, but he was able to deliver a speech in San Jose, California on May 13 and to attend his parade in San Francisco on May 14. The president went to Oakland without his wife, to speak on May 17. The President visited the Union Iron Works of San Francisco to observe the launching of the battleship, USS Ohio (BB-12). Mrs. William McKinley attended the ceremony, but the First Lady became critically (though temporarily) ill in San Francisco and a planned tour of the Northwest was cancelled.[98]

Assassination

The President and Mrs. McKinley spent the summer of 1901 at home in Clinton, Ohio and then attended the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York beginning in late August.[99] He delivered a speech about his positions on tariffs and foreign trade on September 5, 1901. The following morning, McKinley visited Niagara Falls before returning to the Exposition. That afternoon McKinley had an engagement to greet the public at the Temple of Music. Standing in line, Leon Frank Czolgosz waited with a .32 caliber pistol in his right hand concealed by a handkerchief. At 4:07 pm Czolgosz fired twice at the president. The first bullet grazed his shoulder, but the second went through his stomach, pancreas, and kidney, and finally lodged in the muscles of his back. McKinley whispered to his secretary, George Cortelyou, “My wife, Cortelyou, be careful how you tell her, oh be careful.”[100] Czolgosz would have fired again, but he was struck by a bystander and then subdued by an enraged crowd. The wounded McKinley reportedly called out, "Boys! Don't let them hurt him!"[101] because the angry crowd beat Czolgosz so severely it looked as if they might kill him on the spot.

One bullet was easily found and extracted, but doctors were unable to locate the second bullet. It was feared that the search for the bullet might cause more harm than good. In addition, McKinley appeared to be recovering, so doctors decided to leave the bullet where it was.[102]

The newly developed x-ray machine was displayed at the fair, but doctors were reluctant to use it on McKinley to search for the bullet because they did not know what side effects it might have on him. The operating room at the exposition's emergency hospital did not have any electric lighting, even though the exteriors of many of the buildings at the extravagant exposition were covered with thousands of light bulbs. The surgeons were unable to operate by candlelight because of the danger created by the flammable ether used to keep the president unconscious, so doctors were forced to use pans instead to reflect sunlight onto the operating table while they treated McKinley's wounds.

McKinley's doctors believed he would recover, and he convalesced for more than a week in Buffalo at the home of the exposition's director. On the morning of September 12, he felt strong enough to receive his first food orally since the shooting – toast and a small cup of coffee.[103] However, by afternoon he began to experience discomfort and his condition rapidly worsened. McKinley began to go into shock. At 2:15 am on September 14, 1901, eight days after he was shot, he died at age 58 from gangrene surrounding his wounds.[104] His last words were, "It is God's way; His will be done, not ours."[105] He was originally buried in the receiving vault of West Lawn Cemetery in Canton, Ohio. His remains were later reinterred in the McKinley Memorial, also in Canton.

The scene of the assassination, the Temple of Music, was demolished in November 1901, along with the rest of the Exposition grounds. A stone marker in the middle of Fordham Drive, a residential street in Buffalo, marks the approximate spot where the shooting occurred. Czolgosz's revolver is on display in the Pan-American Exposition exhibit at the Buffalo and Erie County Historical Society in Buffalo.

McKinley was the last veteran of the American Civil War in the White House; he was the last president of the 19th century and the first of the 20th.

-

McKinley entering the Temple of Music shortly before his assassination.

-

Leon Czolgosz shoots President McKinley with a concealed revolver.

-

McKinley's coffin passing the Treasury building.

Administration and appointments

The McKinley Cabinet Office Name Term President William McKinley 1897–1901 Vice President Garret A. Hobart 1897–1899 None 1899–1901 Theodore Roosevelt 1901 Secretary of State John Sherman 1897–1898 William R. Day 1898 John Hay 1898–1901 Secretary of Treasury Lyman J. Gage 1897–1901 Secretary of War Russell A. Alger 1897–1899 Elihu Root 1899–1901 Attorney General Joseph McKenna 1897–1898 John W. Griggs 1898–1901 Philander C. Knox 1901 Postmaster General James A. Gary 1897–1898 Charles E. Smith 1898–1901 Secretary of the Navy John D. Long 1897–1901 Secretary of the Interior Cornelius N. Bliss 1897–1899 Ethan A. Hitchcock 1899–1901 Secretary of Agriculture James Wilson 1897–1901 Judicial appointments

Supreme Court

McKinley appointed the following Justice to the Supreme Court of the United States:

- Joseph McKenna – 1898

Other judges

Main article: William McKinley judicial appointmentsAlong with his Supreme Court appointment, McKinley appointed six judges to the United States Courts of Appeals, and 28 judges to the United States district courts.

Monuments and memorials

A funeral was held at the Milburn Mansion in Buffalo, after which the body was removed to Buffalo City Hall where it lay in-state for a public viewing. It was taken later to the White House, United States Capitol and finally to the late President's home in Canton for a memorial. Memorials for the President were held in London, England at Westminster Abbey and St Paul's Cathedral.[106][107]

- William McKinley Presidential Library and Museum, Canton, Ohio.

- McKinley Memorial Mausoleum, Canton, Ohio, his final resting place.

- National McKinley Birthplace Memorial Library and Museum, Niles, Ohio, designed by McKim, Mead and White, dedicated October 5, 1917.[108]

- McKinley Birthplace Home and Research Center, Niles, Ohio, a reconstruction on the site where he was born.

- The statue of McKinley in Muskegon, Michigan is believed to be the first raised in his honor in the country, put in place on May 23, 1902.[109] It was sculpted by Charles Henry Niehaus.

- At Bluff Point, near Plattsburgh, New York, a small monument topped with a memorial urn was erected following the assassination at the site of a large pine tree, known locally as the "McKinley Pine." Beneath this tree, the President would often relax while summering at the nearby Hotel Champlain. One year after the assassination, the tree was struck by lightning and destroyed. Little remains of the monument today.

- McKinley Classical Junior Academy, middle school in St. Louis, Missouri

- McKinley Monument, Buffalo, New York

- McKinley Monument, Springfield, Massachusetts

- McKinley Monument, Scranton, Pennsylvania

- McKinley Statue, Adams, Massachusetts

- William McKinley Monument, Panhandle park and McKinley Square Park, Potrero Hill (dates to 1870, renamed for McKinley), San Francisco, California

- William McKinley Monument, Antietam National Battlefield, Sharpsburg, Maryland (dedicated October 13, 1903)[110]

- Statue of McKinley [Arcata Plaza, Arcata, California]

Film of McKinley's inauguration

McKinley was the first President to appear on film extensively. His inauguration was also the first Presidential inauguration to be filmed. Most of the films were recorded by the Edison Company.

Video clip of the "Black Horse Cavalry" leading the presidential delegation down Pennsylvania Ave. in Washington D.C. for the inauguration of McKinley

See also

- History of the United States (1865-1918)

- List of assassinated American politicians

- List of Presidents of the United States

- U.S. presidential election, 1896

- U.S. presidential election, 1900

- U.S. Presidents on U.S. postage stamps

Notes

- ^ a b c Leech, p. 19.

- ^ Leech, p. 99.

- ^ a b Leech, p. 4.

- ^ "McKinley Family Tree". RootsWeb.com. http://wc.rootsweb.com/cgi-bin/igm.cgi?op=PED&db=:3242853&id=I1812. Retrieved July 18, 2011.

- ^ a b Leech, p. 5.

- ^ "Ohio Fundamental Documents - William McKinley". Ohio History Center. http://www.ohiohistory.org/onlinedoc/ohgovernment/governors/mckinley.html. Retrieved July 18, 2011.

- ^ a b Leech, p. 6.

- ^ a b c Leech, p. 7.

- ^ Leech, pp. 7, 10.

- ^ a b Leech, p. 9.

- ^ a b Leech, p. 10.

- ^ Leech, p. 11.

- ^ Leech, p. 13.

- ^ Leech, p. 12.

- ^ Leech, p. 16.

- ^ a b Leech, p. 17.

- ^ a b Leech, p. 38.

- ^ Leech, p. 37.

- ^ Leech, pp. 42–43.

- ^ Leech, p. 36.

- ^ Leech, p. 35.

- ^ Leech, pp. 50–51.

- ^ Leech, p. 53.

- ^ Leech, p. 54.

- ^ Leech, pp. 55–56.

- ^ Leech, p. 58.

- ^ Leech, p. 61.

- ^ Leech, pp. 75, 82.

- ^ Leech, p. 69.

- ^ Leech, p. 93.

- ^ Leech, p. 89.

- ^ Leech, p. 92.

- ^ Jensen (1971) ch. 10.

- ^ Leech, p. 132.

- ^ Leech, p. 110.

- ^ Josephson, Matthew (1979 (reprint of 1840 version)). The President Makers. New York, New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons. p. 9. ISBN 0-399-50387-0.

- ^ Whitten, David. The Depression of 1893. Eh.net. 2010

- ^ a b c Bahles, Gerald. American President: William McKinley. Miller Center of Public Affairs. 2010

- ^ Leech, p. 135.

- ^ Leech, p. 231.

- ^ Lewis L. Gould, The Presidency of William McKinley (1980) p. 154

- ^ "Walter l. Cohen". Louisiana Historical Assoc.. http://www.lahistory.org/site20.php. Retrieved December 21, 2010.

- ^ a b c McKinley, William (1893). Speeches and addresses of William McKinley: from his election to Congress to the present time. D. Appleton and Company. http://books.google.com/?id=Qe5gk4hoJXAC.

- ^ Leech, p. 146.

- ^ a b c Leech, p. 152.

- ^ a b c Leech, p. 148.

- ^ Lewis Gould, The Spanish–American War and President McKinley (1982)

- ^ Richard Hamilton, President McKinley, War, and Empire (2006)

- ^ Leech, p. 149.

- ^ Leech, p. 163.

- ^ Leech, pp. 156–157.

- ^ Leech, p. 158.

- ^ Leech, pp. 166–168.

- ^ Leech, p. 173.

- ^ Leech, p. 185.

- ^ Leech, p. 182.

- ^ Leech, p. 188.

- ^ a b Leech, p. 169.

- ^ Leech, p. 190.

- ^ a b Leech, p. 191.

- ^ Leech, p. 206.

- ^ Leech, pp. 210–211.

- ^ Leech, p. 213.

- ^ Leech, p. 214.

- ^ Leech, pp. 220–222.

- ^ Leech, pp. 226–227.

- ^ Leech, pp. 244–248.

- ^ Leech, p. 248.

- ^ Leech, p. 245.

- ^ Leech, p. 266.

- ^ Leech, p. 250.

- ^ Leech, p. 369.

- ^ Leech, p. 249

- ^ Leech, p. 251.

- ^ Leech, p. 283.

- ^ Leech, p.330.

- ^ Leech, p.331.

- ^ Leech, p.357.

- ^ a b Gould, The Spanish–American War and President McKinley (1982)

- ^ Louis A. Pérez Jr., "The War of 1898: The United States and Cuba in History and Historiography" (1998)

- ^ Paul Boyer, American Nation in the Modern Era, p. 336.

- ^ Leech, p. 292.

- ^ Leech, pp. 293–309.

- ^ Leech, p. 315.

- ^ Leech, pp. 315-319.

- ^ Schweikart and Allen, p. 470.

- ^ Gould, p.141

- ^ Schweikart and Allen, p. 471.

- ^ Leech, p. 234.

- ^ Leech, p.328.

- ^ Leech, pp. 530–531.

- ^ Leech, pp. 542-543.

- ^ Walter Lafeber, "Election of 1900" in Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., ed. History of American Presidential Elections 1789-1968 (1971) vol. 3.

- ^ Leech, p.559

- ^ Leech, p.567.

- ^ Leech, pp.569–572.

- ^ Leech, p.572

- ^ "Mrs. McKinley in a Critical Condition". The New York Times. May 16, 1901. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=9405E4DB1030E132A25755C1A9639C946097D6CF. Retrieved January 19, 2010.

- ^ Leech, pp.582–583.

- ^ Leech, p. 595.

- ^ truTV.com

- ^ "Biography of William McKinley". http://www.mckinley.lib.oh.us/McKinley/biography.htm. Retrieved December 4, 2006.

- ^ William McKinley: Post-Shooting Medical Course at Medical History of American Presidents

- ^ Rixey P. M., Mann M. D., Mynter H., Park R., Wasdin E., McBurney C., Stockton C. G.: The official report on the case of President McKinley. JAMA 1901; 37: 1029–1059.

- ^ 1920 World Book, Volume VI, p. 3575

- ^ “The McKinley-Roosevelt Administration”, McKinleydeath.com.

- ^ When Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom died on January 22, 1901, flags in the United States were lowered to half-mast in her honor by order of President William McKinley, one which was repaid by Britain when McKinley was assassinated later that year.

- ^ LIB.oh.us

- ^ "Charles Henry Niehaus". 1911Encyclopedia.org. http://www.1911encyclopedia.org/Charles_Henry_Niehaus.

- ^ "Monument to William McKinley". Antietam National Battlefield. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. http://www.nps.gov/anti/historyculture/mnt-mckinley.htm. Retrieved 20 October 2011.

Bibliography

Works cited

- Gould, Lewis L. "McKinley, William"; American National Biography Online (2000)

- Gould, Lewis L. (1981). The Presidency of William McKinley. Regents Press.

- Gould, Lewis L. The Spanish–American War and President McKinley (1982)

- Hamilton, Richard. President McKinley, War, and Empire (2006).

- Jensen, Richard. The Winning of the Midwest: Social and Political Conflict, 1888-1896 (1971)

- Leech, Margaret (1986). In the Days of McKinley. The Easton Press.

- McKinley, William. Speeches and Addresses of William McKinley: from his election to Congress to the present time (1893)

- Morgan, H. Wayne. William McKinley and His America. (1963). biography by scholar

- Olcott, Charles S. The Life of William McKinley. (1916), online at Google

- Schweikart, Larry; Michael Allen (2004). A Patriot's History of the United States. Easton Press.

Other sources

Domestic policy

- Faulkner, Harold U. Politics, Reform, and Expansion, 1890-1900 (1959). standard scholarly survey online edition

- Glad, Paul W. McKinley, Bryan, and the People (1964). short history of 1896 election

- Jones, Stanley L. The Presidential Election of 1896. the standard history.

- Josephson, Matthew. The Politicos: 1865-1896 (1938) a leftist perspective

- Morgan, H. Wayne. From Hayes to McKinley: National Party Politics, 1877-1896 (1969), online edition

- Rhodes, James Ford. The McKinley and Roosevelt Administrations, 1897-1909 (1922), early scholarly history full text online

- Williams, R. Hal. Years of Decision: American Politics in the 1890s (1993) survey by scholar

Foreign policy

- Dobson, John M. Reticient Expansionism: The Foreign Policy of William McKinley. (1988).

- Fry Joseph A. "William McKinley and the Coming of the Spanish-American War: A Study of the Besmirching and Redemption of an Historical Image," Diplomatic History 3 (Winter 1979): 77-97

- Harrington, Fred H. "The Anti-Imperialist Movement in the United States, 1898-1900," Mississippi Valley Historical Review, Vol. 22, No. 2 (Sept. 1935), pp. 211–230 in JSTOR

- Holbo, Paul S. "Presidential Leadership in Foreign Affairs: William McKinley and the Turpie-Foraker Amendment," The American Historical Review 1967 72 (4): 1321-1335. in JSTOR

- May, Ernest. Imperial Democracy: The Emergence of America as a Great Power (1961)

- Offner, John L. "McKinley and the Spanish-American War," Presidential Studies Quarterly Vol. 34#1 (2004) pp 50+. online edition

- Offner, John L. An Unwanted War: The Diplomacy of the United States and Spain over Cuba, 1895-1898 (1992) online edition

- Paterson. Thomas G. "United States Intervention in Cuba, 1898: Interpretations of the Spanish-American-Cuban-Filipino War," The History Teacher, Vol. 29, No. 3 (May 1996), pp. 341–361 in JSTOR

- Trask, David. The War with Spain in 1898. (1981).

Yearbooks

- Appletons' annual cyclopaedia and register of important events...1900 (1901), elaborate compendium of data and some primary sources online edition

Speeches and manuscripts

- McKinley, William. Abraham Lincoln. An Address by William McKinley of Ohio. Before the Marquette Club. Chicago. February 12, 1896(1896)

- McKinley, William. Speeches and Addresses of William McKinley: from March 1, 1897, to May 30, 1900 (1900)

- McKinley, William. The Tariff; a Review of the Tariff Legislation of the United States from 1812 to 1896 (1904)

External links

- William McKinley at the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress Retrieved on 2008-10-19

- William McKinley: A Resource Guide from the Library of Congress

- 1st State of the Union Address

- 2nd State of the Union Address

- 3rd State of the Union Address

- 4th State of the Union Address

- Assassination Site

- Audio clips of McKinley's speeches

- Biography of William McKinley

- Encyclopedia Americana: William McKinley

- First Inaugural Address

- Internet Public Library: William McKinley

- Library of Congress films of McKinley

- Presidential Biography by Stanley L. Klos

- Second Inaugural Address

- McKinley Assassination Ink: A Documentary History

- William McKinley Presidential Library and Memorial

- White House biography

- Works by William McKinley at Project Gutenberg

- Essay on William McKinley and shorter essays on each member of his cabinet and First Lady from the Miller Center of Public Affairs

- "President McKinley is Dead" Macon Telegraph, September 14, 1901, from the Macon Telegraph Archive

- A film clip of William McKinley's inauguration is available for free download at the Internet Archive [more]

- Q&A interview with Scott Miller on The President and the Assassin, June 22, 2011

Articles and topics related to William McKinley Presidents of the United States

- George Washington

- John Adams

- Thomas Jefferson

- James Madison

- James Monroe

- John Quincy Adams

- Andrew Jackson

- Martin Van Buren

- William Henry Harrison

- John Tyler

- James K. Polk

- Zachary Taylor

- Millard Fillmore

- Franklin Pierce

- James Buchanan

- Abraham Lincoln

- Andrew Johnson

- Ulysses S. Grant

- Rutherford B. Hayes

- James A. Garfield

- Chester A. Arthur

- Grover Cleveland

- Benjamin Harrison

- Grover Cleveland

- William McKinley

- Theodore Roosevelt

- William Howard Taft

- Woodrow Wilson

- Warren G. Harding

- Calvin Coolidge

- Herbert Hoover

- Franklin D. Roosevelt

- Harry S. Truman

- Dwight D. Eisenhower

- John F. Kennedy

- Lyndon B. Johnson

- Richard Nixon

- Gerald Ford

- Jimmy Carter

- Ronald Reagan

- George H. W. Bush

- Bill Clinton

- George W. Bush

- Barack Obama

Republican Party Chairpersons

of the RNCMorgan · Raymond · Ward · Claflin · Morgan · Chandler · Cameron · Jewell · Sabin · Jones · Quay · Clarkson · Carter · Hanna · Payne · Cortelyou · New · Hitchcock · Hill · Rosewater · Hilles · Wilcox · Hays · Adams · Butler · Work · Huston · Fess · Sanders · Fletcher · Hamilton · Martin · Walsh · Spangler · Brownell · Reece · Scott · Gabrielson · Summerfield · Roberts · Hall · Alcorn · T. B. Morton · Miller · Burch · Bliss · R. Morton · Dole · Bush · Smith · Brock · Richards · Fahrenkopf · Atwater · Yeutter · Bond · Barbour · Nicholson · Gilmore · Racicot · Gillespie · Mehlman · Martinez · Duncan · Steele · Priebus

Presidential tickets Frémont/Dayton · Lincoln/Hamlin · Lincoln/Johnson · Grant/Colfax · Grant/Wilson · Hayes/Wheeler · Garfield/Arthur · Blaine/Logan · Harrison/Morton · Harrison/Reid · McKinley/Hobart · McKinley/Roosevelt · Roosevelt/Fairbanks · Taft/Sherman/Butler · Hughes/Fairbanks · Harding/Coolidge · Coolidge/Dawes · Hoover/Curtis · Landon/Knox · Willkie/McNary · Dewey/Bricker · Dewey/Warren · Eisenhower/Nixon · Nixon/Lodge · Goldwater/Miller · Nixon/Agnew · Ford/Dole · Reagan/G. H. W. Bush · G. H. W. Bush/Quayle · Dole/Kemp · G. W. Bush/Cheney · McCain/Palin

Parties by state

and territoryStateAlabama · Alaska · Arizona · Arkansas · California · Colorado · Connecticut · Delaware · Florida · Georgia · Hawaii · Idaho · Illinois · Indiana · Iowa · Kansas · Kentucky · Louisiana · Maine · Maryland · Massachusetts · Michigan · Minnesota · Mississippi · Missouri · Montana · Nebraska · Nevada · New Hampshire · New Jersey · New Mexico · New York · North Carolina · North Dakota · Ohio · Oklahoma · Oregon · Pennsylvania · Rhode Island · South Carolina · South Dakota · Tennessee · Texas · Utah · Vermont · Virginia · Washington · West Virginia · Wisconsin · Wyoming

TerritoryDistrict of Columbia · Guam · Northern Mariana Islands · Puerto Rico · Virgin Islands

Conventions

(List)1856 (Philadelphia) · 1860 (Chicago) · 1864 (Baltimore) · 1868 (Chicago) · 1872 (Philadelphia) · 1876 (Cincinnati) · 1880 (Chicago) · 1884 (Chicago) · 1888 (Chicago) · 1892 (Minneapolis) · 1896 (Saint Louis) · 1900 (Philadelphia) · 1904 (Chicago) · 1908 (Chicago) · 1912 (Chicago) · 1916 (Chicago) · 1920 (Chicago) · 1924 (Cleveland) · 1928 (Kansas City) · 1932 (Chicago) · 1936 (Cleveland) · 1940 (Philadelphia) · 1944 (Chicago) · 1948 (Philadelphia) · 1952 (Chicago) · 1956 (San Francisco) · 1960 (Chicago) · 1964 (San Francisco) · 1968 (Miami Beach) · 1972 (Miami Beach) · 1976 (Kansas City) · 1980 (Detroit) · 1984 (Dallas) · 1988 (New Orleans) · 1992 (Houston) · 1996 (San Diego) · 2000 (Philadelphia) · 2004 (New York) · 2008 (St. Paul) · 2012 (Tampa)

Affiliated

organizationsCollege Republicans · Congressional Hispanic Conference · International Democrat Union · Log Cabin Republicans · National Republican Congressional Committee · National Republican Senatorial Committee · Republican Conference of the United States House of Representatives · Republican Conference of the United States Senate · Republican Governors Association · Republican Jewish Coalition · Republican Liberty Caucus · Republican Main Street Partnership · Republican Majority for Choice · Republican National Coalition for Life · Republican National Hispanic Assembly · Republican Study Committee · Republicans Abroad · Republicans for Environmental Protection · The Ripon Society · The Wish List · Young Republicans

Related articles History · 2009 chairmanship election · 2011 chairmanship election · Bibliography · Timeline of modern American conservatism

Governors and Lieutenant Governors of Ohio

Governors Tiffin · Kirker · Huntington · Meigs · Looker · Worthington · E. Brown · Trimble · Morrow · Trimble · McArthur · Lucas · Vance · Shannon · Corwin · Shannon · T. Bartley · M. Bartley · Bebb · Ford · Wood · Medill · Chase · Dennison · Tod · Brough · Anderson · J. D. Cox · Hayes · Noyes · Allen · Hayes · Young · Bishop · Foster · Hoadly · Foraker · Campbell · McKinley · Bushnell · Nash · Herrick · Pattison · Harris · Harmon · J. M. Cox · Willis · J. M. Cox · Davis · Donahey · Cooper · White · Davey · Bricker · Lausche · Herbert · Lausche · J. Brown · O'Neill · DiSalle · Rhodes · Gilligan · Rhodes · Celeste · Voinovich · Hollister · Taft · Strickland · KasichLieutenant

GovernorsMedill · Myers · Ford · Welker · Kirk · Stanton · Anderson · McBurney · Lee · Mueller · Hart · Young · Curtiss · Fitch · Hickenlooper · Richards · Warwick · Kennedy · Conrad · Lyon · Lampson · Marquis · Harris · Jones · Caldwell · Nippert · Gordon · Harding · Harris · Treadway · Pomerene · Nichols · Greenlund · Arnold · Bloom · C. Brown · Bloom · Lewis · Bloom · Pickrel · Braden · J. T. Brown · Pickrel • Sawyer · Mosier · Yoder · Herbert · Nye · Herbert · Nye · J. W. Brown · Herbert · Donahey · J. W. Brown · Celeste · Voinovich · Shoemaker · Leonard · DeWine · Hollister · O'Connor · Bradley · Johnson · Fisher · TaylorCabinet of President William McKinley (1897–1901) Vice President

Secretary of State Secretary of the Treasury Secretary of War Attorney General Postmaster General Secretary of the Navy Secretary of the Interior Secretary of Agriculture  Philippine Revolution (1896–1898)

Philippine Revolution (1896–1898)

Events PreludeGomburza · Cry of Pugad Lawin · Katagalugan (Bonifacio) · Tejeros Convention · Republic of Biak-na-Bato · Biak-na-Bato Elections · Pact of Biak-na-Bato · Spanish-American War · Declaration of Independence · Malolos Congress · República Filipina · Negros Revolution · Treaty of Paris · Philippine–American War · Katagalugan (Sacay) · Republic of Zamboanga · Moro Rebellion ·EpilogueOrganizations American Anti-Imperialist League · Aglipayan Church · Katipunan · La Liga Filipina · La Solidaridad · Magdalo faction · Magdiwang faction · Philippine Constabulary · Philippine Revolutionary Army · Pulajanes · Propaganda Movement · Republic of NegrosObjects People Juan Abad · Gregorio Aglipay · Baldomero Aguinaldo · Emilio Aguinaldo · Vicente Alvarez · Melchora Aquino · Juan Araneta · Bonifacio Flores Arevalo · Andrés Bonifacio · Josephine Bracken · Dios Buhawi · Francisco Carreón · Ladislao Diwa · Gregoria de Jesús · Gregorio del Pilar · Marcelo H. del Pilar · George Dewey · Papa Isio · Emilio Jacinto · Antonio Ledesma Jayme · León Kilat · Aniceto Lacson · Francisco Tongio Liongson · Graciano López Jaena · Vicente Lukbán · Antonio Luna · Juan Luna · Apolinario Mabini · Sultan of Maguindanao · Miguel Malvar · Arcadio Maxilom · William McKinley · Patricio Montojo · Simeón Ola · José Palma · Pedro Paterno · Mariano Ponce · Artemio Ricarte · José Rizal · Paciano Rizal · Macario Sakay · Sultan of Sulu · Martin Teofilo Delgado · Manuel Tinio · Mariano Trías · Trece MartiresCategories:- 1843 births

- 1901 deaths

- Albany Law School alumni

- Allegheny College alumni

- American Methodists

- American people of English descent

- American people of Scotch-Irish descent

- Assassinated United States Presidents

- Deaths by firearm in New York

- Deaths from gangrene

- Governors of Ohio

- History of the United States (1865–1918)

- Members of the United States House of Representatives from Ohio

- Ohio Republicans

- People from Canton, Ohio

- People from Niles, Ohio

- People murdered in New York

- People of the Spanish–American War

- Presidents of the United States

- Progressive Era in the United States

- Republican Party Presidents of the United States

- Republican Party state governors of the United States

- Republican Party (United States) presidential nominees

- Union Army officers

- United States Army officers

- United States presidential candidates, 1892

- United States presidential candidates, 1896

- United States presidential candidates, 1900

- University of Mount Union alumni

- William McKinley

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.