- Thomas Brackett Reed

-

For other people named Thomas Reed, see Thomas Reed (disambiguation).

Thomas Brackett Reed

38th Speaker of the United States House of Representatives In office

December 2, 1895 – March 4, 1899President Grover Cleveland

William McKinleyPreceded by Charles F. Crisp Succeeded by David B. Henderson 36th Speaker of the United States House of Representatives In office

December 4, 1889 – March 4, 1891President Benjamin Harrison Preceded by John G. Carlisle Succeeded by Charles F. Crisp Member of U.S. House of Representatives

from Maine's 1st districtIn office

March 4, 1877 – September 4, 1899Preceded by John H. Burleigh Succeeded by Amos L. Allen Personal details Born October 18, 1839

Portland, MaineDied December 7, 1902 (aged 63)

Washington, D.C.Political party Republican Alma mater Bowdoin College Profession Law Thomas Brackett Reed, (October 18, 1839 – December 7, 1902), occasionally ridiculed as Czar Reed, was a U.S. Representative from Maine, and Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives from 1889–1891 and from 1895–1899. He was a powerful leader of the Republican Party, and during his tenure as Speaker of the House, he served with greater influence than any Speaker who came before, and he forever increased its power and influence for those who succeeded him in the position.

Contents

Political life

Born in Portland, Maine, Reed attended public school, including Portland High School, before graduating from Bowdoin College in 1860. He studied law. After college, he went on to become acting assistant paymaster, United States Navy, from April 1864, to November 1865, and was admitted to the bar in 1865. He practiced in Portland, and was elected to the Maine House of Representatives, in 1868 and 1869. He served in the Maine Senate in 1870 but left to serve as the state's Attorney General 1870–72. Reed became city solicitor of Portland 1874–1877, before being elected as a Republican to the Forty-fifth and to the eleven succeeding Congresses, serving from 1877, to September 4, 1899, when he resigned.[1]

In the House of Representatives

Early service

Acerbic wit

He was known for his acerbic wit (asked if his party might nominate him for President, he noted "They could do worse, and they probably will"). His size, standing at over 6 feet in height and weighing over 300 lbs (136 kg), was also a distinguishing factor for him. Reed was a member of the social circle that included intellectuals and politicians Sen. Henry Cabot Lodge, Theodore Roosevelt, Henry Adams, John Hay and Mark Twain.

As a House freshman, Reed was appointed to the Potter Commission, which was to investigate voting irregularities in the presidential election of 1876, where his skill at cross examination forced Democrat Samuel J. Tilden to personally appear to defend his reputation. He chaired of the Committee on the Judiciary (Forty-seventh Congress) and chaired the Rules Committee (Fifty-first, Fifty-fourth, and Fifty-fifth Congresses).

As the Speaker of the House

Reed was first elected Speaker after an intense fight with William McKinley of Ohio. Reed gained the support of young Theodore Roosevelt, whose influence as the newly appointed Civil Service Commissioner was the decisive factor. Reed served as the Speaker of the United States House of Representatives from 1889 to 1891 and then from 1895 to 1899, as well as being Chairman of the powerful Rules Committee.

Rules

During his time as Speaker, Reed assiduously and dramatically increased the power of the Speaker over the House; although the power of the Speaker had always waxed (most notably during Henry Clay's tenure) and waned, the position had previously commanded influence rather than outright power. Reed set out to put into practical effect his dictum that "The best system is to have one party govern and the other party watch"; this was accomplished by carefully studying the existing procedures of the U.S. House, most dating to the original designs written by Thomas Jefferson. In particular, Reed sought to circumscribe the ability of the minority party to block business by way of its members refusing to answer a quorum call — which, under the rules, prevented a member from being counted as present even if they were physically in the chamber — thus forcing the House to suspend business. This is popularly called the disappearing quorum.

Reed's solution was enacted on January 28, 1890, in what has popularly been called the "Battle of the Reed Rules".[2] This came about when Democrats attempted to block the inclusion of a newly elected Republican from West Virginia, Charles Brooks Smith.[3] The motion to seat him passed by a tally of 162–1; however, at the time a quorum consisted of 165 votes, and when voting closed Democrats shouted "No quorum," triggering a formal House quorum count. Speaker Reed began the roll call; when members who were present in the chamber refused to answer, Reed directed the Clerk to count them as present anyway.[4] Startled Democrats protested heatedly, issuing screams, threats, and insults at the Speaker. James B. McCreary, a Democrat from Kentucky, challenged Reed's authority to count him as present; Reed replied, "The Chair is making a statement of fact that the gentleman from Kentucky is present. Does he deny it?"[4]

Unable to deny their presence in the chamber, Democrats then tried to flee the chamber, but Reed ordered the doors locked. (Texas Representative "Buck" Kilgore was able to flee by kicking his way through a door.) [5] Trapped, the Democrats tried to hide under their desks and chairs; Reed marked them present anyway.

The conflict over parliamentary procedure lasted three days, with Democrats delaying consideration of the bill by introducing points of order to challenge the maneuver, then appealing the Reed's rulings to the floor. Democrats finally dropped their objections on January 31, and Smith was seated on February 3 by a vote of 166–0. Six days later, with Smith seated, Reed successfully won a vote on his new "Reed Rules," eliminating the disappearing quorum and lowering the quorum to 100 members. Though Democrats reinstated the disappearing quorum when they took control of the House the following year, Reed as minority leader proved so adroit at using the tactic against them that Democrats reinstated Reed Rules in 1894.[6]

Civil Rights

In 1889–90, Republicans undertook one last stand in favor of federal enforcement of the Fifteenth Amendment to protect the voting rights of blacks in the Solid South. Reed took a special interest in the project. Using his new rules vigorously, he won passage of the Lodge Fair Elections Bill in the House in 1890. The bill was later defeated in a filibuster in the Senate when Silver Republicans in the West traded it away for the Sherman Silver Purchase Act.[7]

Presidential aspirations and departure from Congress

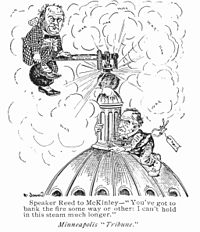

Reed tried to obtain the Republican nomination for President in 1896, but Ohio Governor McKinley's campaign manager, Mark Hanna, blocked his efforts.

In 1898 Reed supported McKinley in efforts to head off war with Spain. When McKinley switched to support for the war, Reed disagreed. He resigned from the speakership and from his seat in Congress in 1899 to enter private law practice.[8]

On a nostalgic trip to Washington in 1902 he had a sudden heart attack and died; Henry Cabot Lodge eulogized him as "a good hater, who detested shams, humbugs and pretense above all else." He was buried in Evergreen Cemetery in Portland, Maine. His will was executed by his good friend Augustus G. Paine, Sr. from New York.[9]

Landmarks

Statue of Reed on Portland, Maine's Western Promenade in September 2011

Statue of Reed on Portland, Maine's Western Promenade in September 2011

The coastal town of Reed, Oregon, was named after him.[10] There is a Reed House at Bowdoin College.[11]

His home town of Portland, Maine, erected a statue of him at the corner of Western Promenade and Pine St[12] in a ceremony on August 31, 1910.[13]

In 1894, he published his handbook on parliamentary procedure, titled Reed's Rules: A Manual of General Parliamentary Law, which was, at the time, a very popular text on the subject and is still in use in the legislature of the State of Washington.

Biographies

Biographies of the life of Thomas Brackett Reed have been written by Richard Stanley Offenberg, in 1963, and by Mead Dodd in 1930. Most recently, finance writer James Grant wrote the biography entitled, "Mr. Speaker! The Life and Times of Thomas B. Reed: the Man who Broke the Filibuster."

References

- ^ Samuel W. McCall, Thomas B. Reed (1914) ch 1–3

- ^ Samuel W. McCall, Thomas B. Reed (1914) pp 152–72

- ^ Price, Douglas H. ``The Congressional Career—Then and Now, in Nelson Polsby, ed., Congressional Behavior (New York: Random House, 1971), p. 19.

- ^ a b Representative Thomas B. Reed, remarks in the House, Congressional Record, vol. 61, Jan. 29, 1890, p. 948.

- ^ Roger Place Butterfield, The American Past (1966) p. 254

- ^ House Document No. 108-204: The Cannon Centenary Conference: The Changing Nature of the Speakership

- ^ Wendy Hazard, "Thomas Brackett Reed, Civil Rights, and the Fight for Fair Elections," Maine History, March 2004, Vol. 42 Issue 1, pp 1–23

- ^ Samuel W. McCall, Thomas B. Reed (1914) pp 231–39

- ^ "Obituary Augustus G. Paine". New York Times. March 27, 1915. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F60815F9395C13738DDDAE0A94DB405B858DF1D3&scp=2&sq=augustus%20g.%20paine&st=cse. Retrieved November 15, 2010.

- ^ Bob Welch. "Of cranes with trees and bands on knees". Register-Guard. Dec 16, 2007. http://blogs.registerguard.com/cms/index.php/close-to-home/comments/qa_dec_16/ Accessed April 21, 2009.

- ^ "Reed (Bowdoin, Residential Life)". Bowdoin College. Archived from the original on December 24, 2010. http://www.webcitation.org/5vDvGF5jF. Retrieved December 24, 2010. "Reed House formerly Alpha Eta of Chi Psi was dedicated on September 28, 2007 in memory of Thomas Brackett Reed (1839–1902)"

- ^ Robert Klotz. "Portland Locations with National Political Significance". Portland Political Trail. Accessed April 21. http://www.usm.maine.edu/~rklotz/exhibits/revtrail.htm

- ^ Anon.. Exercises at the Unveiling of the Statue of Thomas Brackett Reed, at Portland, Maine, August Thirty-First, Nineteen Hundred and Ten. Read Books. p. 10. ISBN 9781408669211. http://books.google.com/books?id=bxsQ3U3FmHAC&pg=PA6#v=onepage&q=&f=false.

Bibliography

- Hazard, Wendy. "Thomas Brackett Reed, Civil Rights, and the Fight for Fair Elections," Maine History, March 2004, Vol. 42 Issue 1, pp 1–23

- McCall, Samuel W. Thomas B. Reed (1914) excerpt and text search

- Strahan, Randall (2007). Leading Representatives: The Agency of Leaders in the Politics of the U.S. House. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-8691-0.

- Tuchman, Barbara Wertheim (1996). The proud tower: a portrait of the world before the war, 1890–1914. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-345-40501-2.

Primary sources

- Roosevelt, Theodore; Reed, Thomas B. "'Dear Tom,' 'Dear Theodore': The Letters of Theodore Roosevelt and Thomas B. Reed," edited by R. Hal Williams, Theodore Roosevelt Association Journal, July 1994, Vol. 20 Issue 3/4, pp3–22, 20p. 23 letters from 1888–1902 discuss the Republican Party and its leaders, foreign policy, the gold and silver issues, New York State politics, and TR's activity as police commissioner of New York City.

External links

- Thomas Brackett Reed at the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress

- Works by Thomas Brackett Reed at Project Gutenberg

- Reed's Rules, a manual of general parliamentary law (1894) http://www.leg.wa.gov/documents/legislature/reedsrules/reeds.htm

- Political cartoon, NY Times/Harper's Weekly, December 21, 1895 Our American Czar and His Do-Nothing Policy

- Thomas Brackett Reed at Find a Grave

- Mr. Speaker! The Life and Times of Thomas B Reed The Man Who Broke The Filibuster

Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). "Reed, Thomas Brackett". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). "Reed, Thomas Brackett". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

United States House of Representatives Preceded by

John H. BurleighMember of the U.S. House of Representatives

from Maine's 1st congressional district

March 4, 1877 – September 4, 1899Succeeded by

Amos L. AllenPolitical offices Preceded by

John G. CarlisleSpeaker of the U.S. House of Representatives

December 2, 1889 – March 4, 1891Succeeded by

Charles F. CrispPreceded by

Charles F. CrispSpeaker of the U.S. House of Representatives

December 2, 1895 – March 4, 1897;

March 15, 1897 – March 4, 1899Succeeded by

David B. HendersonSpeakers of the United States House of Representatives Muhlenberg · Trumbull · Muhlenberg · Dayton · Sedgwick · Macon · Varnum · Clay · Cheves · Clay · Taylor · Barbour · Clay · Taylor · Stevenson · Bell · Polk · Hunter · White · Jones · Davis · Winthrop · Cobb · Boyd · Banks · Orr · Pennington · Grow · Colfax · Pomeroy · Blaine · Kerr · Randall · Keifer · Carlisle · Reed · Crisp · Reed · Henderson · Cannon · Clark · Gillett · Longworth · Garner · Rainey · Byrns · Bankhead · Rayburn · Martin · Rayburn · Martin · Rayburn · McCormack · Albert · O'Neill · Wright · Foley · Gingrich · Hastert · Pelosi · BoehnerCategories:- 1839 births

- 1902 deaths

- Speakers of the United States House of Representatives

- Bowdoin College alumni

- Paymasters

- Members of the United States House of Representatives from Maine

- Maine Attorneys General

- Members of the Maine House of Representatives

- Portland, Maine politicians

- Maine Republicans

- Burials at Evergreen Cemetery (Portland, Maine)

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.