- OK Computer

-

OK Computer

Studio album by Radiohead Released - 21 May 1997 (Japan)

- 16 June 1997 (UK)

- 1 July 1997 (US)

Recorded - July 1996 at Canned Applause in Didcot

- September 1996 – March 1997 at St Catherine's Court in Bath

Genre Alternative rock Length 53:27 Label Parlophone (UK), Capitol (US) Producer Radiohead, Nigel Godrich Radiohead chronology The Bends

(1995)OK Computer

(1997)Kid A

(2000)Singles from OK Computer - "Paranoid Android"

Released: May 1997 - "Karma Police"

Released: August 1997 - "No Surprises"

Released: January 1998

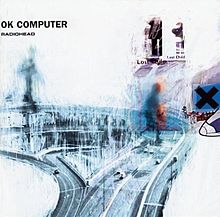

OK Computer is the third studio album by the English alternative rock band Radiohead, released on 16 June 1997 on Parlophone in the UK and 1 July 1997 by Capitol Records in the US. It marks a deliberate attempt by the band to move away from the introspective guitar-oriented sound of their previous album The Bends. Its layered sound and wide range of influences set it apart from many of the Britpop and alternative rock bands popular at the time and laid the groundwork for Radiohead's later, more experimental work.

OK Computer was the first self-produced Radiohead album, with assistance from Nigel Godrich. Radiohead recorded the album in Oxfordshire and Bath between 1996 and early 1997, with most of the recording completed in the historic mansion St. Catherine's Court. On delivery to Capitol, the label lowered its sales estimates due to the album's unconventional, unmarketable sound. Nevertheless, OK Computer reached number one on the UK Albums Chart and became Radiohead's highest album entry on the American charts at the time, debuting at number 21 on the Billboard 200. Three singles—"Paranoid Android", "Karma Police" and "No Surprises"—were released in promotion of the album.

The album built on the band's worldwide popularity and has to date sold over 4.5 million copies. It received considerable acclaim at release, and is frequently cited by critics as one of the greatest albums ever recorded. Its influence on later musicians marks the transition from Britpop to the more melancholic and atmospheric style of latter-day alternative rock. Critics and fans often remark on the underlying themes found in the lyrics and artwork emphasising views on rampant consumerism, social disconnection, political stagnation and malaise. An LP reissue in 2008 contributed to a popular revival of vinyl records, and an expanded CD reissue in 2009, released without the band's foreknowledge or permission, brought renewed attention to the album and its legacy.

Contents

Background

Thom Yorke (pictured in 2005) and the band sought a less melancholy direction than previous album The Bends.

Thom Yorke (pictured in 2005) and the band sought a less melancholy direction than previous album The Bends.

In 1995, Radiohead—singer Thom Yorke, guitarists Jonny Greenwood and Ed O'Brien, bassist Colin Greenwood and drummer Phil Selway—were touring in support of their highly acclaimed second album The Bends. Midway through the tour, Brian Eno requested that Radiohead contribute a song to The Help Album, a charity compilation organized by War Child to benefit children affected by the Bosnian War. The Help Album sessions were to take place over the course of only a single day, 4 September 1995, and rush-released later that week.[1] That day the band recorded the song "Lucky", which they had written while on tour, in five hours.[2] The song was released on The Help Album and as the lead track on a promotional Help EP, but BBC Radio 1 chose not to play the track and the EP only reached 51 on the UK Charts.[3] Yorke was disappointed with the song's commercial performance,[3] but later said that "Lucky" crucially shaped the nascent sound and mood of their upcoming record:[2] "'Lucky' was indicative of what we wanted to do. It was like the first mark on the wall."[4] The song would eventually be included on OK Computer.

Radiohead found the tour to be stressful and draining and took a break in January 1996.[5] In the aftermath, Radiohead sought to distance their new material from the musical style of The Bends. Selway said, "The Bends was an introspective album ... There was an awful lot of soul searching. To do that again on another album would be excruciatingly boring."[6] Yorke, the band's primary lyricist, said, "The big thing for me is that we could really fall back on just doing another miserable, morbid and negative record lyrically, but I don't really want to, at all. And I'm deliberately just writing down all the positive things that I hear or see. I'm not able to put them into music yet and I don't want to just force it."[7]

The critical and commercial success of The Bends gave the band the self confidence to self-produce their third album.[2] A number of producers, including major figures like Scott Litt, were offered the job,[8] but the band were encouraged by recording sessions with engineer Nigel Godrich, who had assisted John Leckie with The Bends and had produced several Radiohead B-sides.[9] Greenwood said "the only concept that we had for this album was that we wanted to record it away from the city and that we wanted to record it ourselves."[10] The group prepared for the recording sessions by buying their own recording equipment, including a plate reverberator purchased from Jona Lewie.[2] Radiohead consulted Godrich for advice on what equipment to use.[11] Although Godrich sought to shift the focus of his production work away from rock music and to electronic dance music,[12] he outgrew his role as advisor and became co-producer on the album.[11]

Recording

In early 1996, Radiohead started rehearsing and recording OK Computer in the Canned Applause studio, a converted shed near Didcot, Oxfordshire. It was the band's first attempt to work outside a conventional studio environment. Colin Greenwood said, "We had this mobile-studio type of thing going where we could take it all into studios to capture those environments. We recorded about 35% of the album in our rehearsal space. You had to piss around the corner because there were no toilets or no running water. It was in the middle of the countryside. You had to drive to town to find something to eat."[10]

To avoid the tension that accompanied the recording sessions for The Bends, EMI did not impose a production deadline on Radiohead.[13] The band still ran into problems which Selway blamed on their choice to self-produce the album. All five members had differing opinions and equal production roles, with Yorke having "the loudest voice", according to O'Brien. Radiohead eventually decided that Canned Applause was an unsatisfactory recording location. Yorke attributed the discontent to its proximity to the band members' homes, while Jonny Greenwood cited its lack of dining and bathroom facilities.[14] In spite of these difficulties, the group had nearly completed recording four songs—"Electioneering", "No Surprises", "Subterranean Homesick Alien" and "The Tourist"—when they left Canned Applause.[15]

At their label's request, the band took a break from recording to embark on a 13-date American tour, opening for Alanis Morissette, where they performed early versions of several of their new songs. During the summer 1996 tour one of the new songs, "Paranoid Android", evolved from a fourteen-minute song featuring long organ solos to one closer to the six-minute album version.[16] During the tour, filmmaker Baz Luhrmann commissioned Radiohead to write a song for his upcoming film Romeo + Juliet. Luhrman gave the band footage of the final 30 minutes of the film, and Yorke said "When we saw the scene in which Claire Danes holds the Colt 45 against her head, we started working on the song immediately."[17] Soon afterwards, the band wrote and recorded "Exit Music (For a Film)"; the track plays over the film's end credits but was not included on the soundtrack at the band's request.[18] Yorke later said that the song helped shape the direction of the rest of the album, and that it "was the first performance we'd ever recorded where every note of it made my head spin – something I was proud of, something I could turn up really, really loud and not wince at any moment."[2]

Most of OK Computer was recorded between September and October 1996 at St Catherine's Court (pictured), a rural mansion near Bath, Somerset.

Most of OK Computer was recorded between September and October 1996 at St Catherine's Court (pictured), a rural mansion near Bath, Somerset.

Radiohead resumed their recording sessions in September 1996 at St Catherine's Court, a historic mansion near Bath owned by actress Jane Seymour.[19] The group made much use of the different rooms and atmospheres throughout the house: the vocals on "Exit Music (For a Film)" featured an echo effect achieved by recording on a stone staircase, and "Let Down" was recorded at 3 AM in a ballroom.[20] The isolation from the outside world allowed the band to work at a different pace, with more flexible and spontaneous working hours. O'Brien said that "the biggest pressure was actually completing [the recording]. We weren't given any deadlines and we had complete freedom to do what we wanted. We were delaying it because we were a bit frightened of actually finishing stuff."[21] Yorke was ultimately satisfied with the quality of the recordings made at the location, and later said "In a big country house, you don't have that dreadful '80s 'separation'. ... There wasn't a desire for everything to be completely steady and each instrument recorded separately."[22] O'Brien was similarly pleased with the recordings, estimating that 80 per cent of the album was recorded live. He noted, "I hate doing overdubs, because it just doesn't feel natural. ... Something special happens when you're playing live; a lot of it is just looking at one another and knowing there are four other people making it happen."[22]

Radiohead returned to Canned Applause in October for rehearsals,[23] and completed most of the album during further sessions at St. Catherine's Court. By Christmas, they had narrowed the track listing down to 14 songs.[24] The album's string parts were recorded at Abbey Road Studios in London in January 1997. The album was mastered at the same location, and mixed over the next two months at various studios around the city.[25]

Music and lyrics

Yorke explained that the starting point for the record was the "incredibly dense and terrifying sound" of Bitches Brew, a 1969 avant-garde jazz fusion album by Miles Davis.[26] He described the sound of Bitches Brew to Q: "It was building something up and watching it fall apart, that’s the beauty of it. It was at the core of what we were trying to do with OK Computer."[27] Yorke has identified "I'll Wear It Proudly" by Elvis Costello, "Fall on Me" by R.E.M., "Dress" by PJ Harvey and "A Day in the Life" by The Beatles as being particularly influential on the album's songwriting.[2] Radiohead drew further inspiration from the film soundtrack composer Ennio Morricone and the krautrock band Can, musicians Yorke described as motivated by "abusing the recording process".[2] According to Yorke, the band hoped to achieve an "atmosphere that's perhaps a bit shocking when you first hear it, but only as shocking as the atmosphere on The Beach Boys' Pet Sounds."[26]

Jonny Greenwood (pictured in concert in 2006) used a broader range of instruments on OK Computer than on previous releases, including glockenspiel.[28]

Jonny Greenwood (pictured in concert in 2006) used a broader range of instruments on OK Computer than on previous releases, including glockenspiel.[28]

The band expanded their instrumentation to include electric piano, Mellotron, cello and other strings, glockenspiel and electronic effects. The band's more exploratory approach to instruments was summarized by Jonny Greenwood as "when we’ve got what we suspect to be an amazing song, but nobody knows what they’re gonna play on it."[28] One reviewer characterised OK Computer as sounding like "a DIY electronica album made with guitars".[29] Many of Yorke's vocals were first takes; he felt that if he made other attempts he would "start to think about it and it would sound really lame."[27]

Yorke's lyrics on the album are more abstract compared to his personal, emotional lyrics for The Bends. He said, "On this album, the outside world became all there was... I'm just taking Polaroids of things around me moving too fast."[30] He explained that "It was like there's a secret camera in a room and it's watching the character who walks in—a different character for each song. The camera's not quite me. It's neutral, emotionless. But not emotionless at all. In fact, the very opposite."[31] Many of Yorke's lyrics were inspired by books he read at the time, including Noam Chomsky's writings,[32] Eric Hobsbawm's The Age of Extremes, Will Hutton's The State We’re In, Jonathan Coe's What a Carve Up! and Phillip K. Dick's VALIS.[33] Themes that pervade the album include transport, technology, insanity, death, modern life in the UK, globalisation and political objection to capitalism.[34] Although the songs have common themes, any clear story is unintentional and Radiohead do not deem OK Computer to be a concept album.[35] However, the album was meant to be heard as a whole; O'Brien said, "We spent two weeks track-listing the album. The context of each song is really important... It's not a concept album but there is a continuity there."[35]

Tracks 1-6

Opening track "Airbag" was inspired by DJ Shadow and is underpinned by an electronic drum beat programmed from a seconds-long recording of Selway's drumming. The band sampled the drum track with an Akai S3000XL and edited it with a Macintosh, but admitted to making approximations in emulating Shadow's style due to their programming inexperience.[36][37] The bassline in "Airbag" stops and starts unexpectedly, and according to Colin Greenwood "I thought I'd probably think of something to put in the gaps later, but I never got around to it."[38] The song's references to automobile accidents and reincarnation, were inspired by a magazine article titled "An Airbag Saved My Life" and The Tibetan Book of the Dead. Yorke wrote "Airbag" about "the idea that whenever you go out on the road you could be killed."[39]

"Paranoid Android" is the band's second-longest recorded studio track as of 2011 at 6:23. The unconventional multi-section structure of the song was inspired by similarly structured rock songs, such as The Beatles' "Happiness Is a Warm Gun" and Queen's "Bohemian Rhapsody".[40] The song's musical style was also inspired by the music of the Pixies.[41] Colin Greenwood said that the song is "just a joke, a laugh, getting wasted together over a couple of evenings and putting some different pieces together."[42] The song was written by Yorke after an unpleasant night at a Los Angeles bar, particularly a woman who reacted violently after someone spilled a drink on her.[31] Its title and lyrics reference Marvin the Paranoid Android from Douglas Adams's The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy.[41]

The use of electric keyboards in "Subterranean Homesick Alien" is an example of the band's attempts to emulate the atmosphere of Bitches Brew.[43] The title is a reference to the Bob Dylan song "Subterranean Homesick Blues", and the song has a science fiction-theme in which the isolated narrator longs to be abducted by extraterrestrials to see "the world as I'd love to see it". Upon returning to Earth, the narrator speculates that his friends would not believe his story and he would remain a misfit.[44] The lyrics were inspired by a school assignment from Yorke's time at Abingdon School to write a piece of "Martian poetry", a British literary movement of works that humorously recontextualizes mundane aspects of human life from an alien "Martian" perspective.[45] Yorke says the song explores his fascination with "the idea of someone observing how we live from the outside ... and sitting there pissing themselves laughing at how humans go about their daily business."[46]

William Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet, particularly the 1968 film adaptation,[47] inspired the lyrics for "Exit Music (For a Film)".[41] Initially Yorke had wanted to incorporate lines from the play into the lyrics, but ultimately the lyrics became a broad summary of the narrative.[48] Yorke compared the opening of the song, which mostly features his singing paired with acoustic guitar, to Johnny Cash's At Folsom Prison.[49] The synthesized sound of a choir and other electronic voices are used throughout the track.[50] The climax of the song opens with drumming[50] and prominently features distorted bass run through a fuzz pedal,[51] which Yorke called "the most significant thing in 'Exit Music' ... It’s incredibly brutal."[52] The second portion of the song is an attempted emulation of the sound of trip hop group Portishead but is, according to Colin Greenwood, more "stilted and leaden and mechanical".[53]

"Let Down" contains multilayered arpeggiated guitars and electric piano. Jonny Greenwood plays a guitar part in a different time signature to the other instruments.[54] O’Brien said the song was influenced by Phil Spector, a producer best known for his reverberating "Wall of Sound" production style.[36] Music journalist Tim Footman described the style of the song as a mix of the jangling 1980s indie pop aesthetic, exemplified by the C86 compilation, and the keyboard intro to The Who's "Baba O'Riley".[55] The song's lyrics are, Yorke says, "about that feeling that you get when you're in transit but you're not in control of it—you just go past thousands of places and thousands of people and you're completely removed from it."[41] Commenting on one of the song's lines, "Don't get sentimental/It always ends up drivel", Yorke said: "Sentimentality is being emotional for the sake of it. We're bombarded with sentiment, people emoting. That's the Let Down. Feeling every emotion is fake. Or rather every emotion is on the same plane whether it's a car advert or a pop song."[27] Yorke felt that this skepticism toward emotion was pervasive in Generation X and said that it informed not just "Let Down" but the overall approach to the album.[56]

Critic Steve Huey says the structure of "Karma Police" is "somewhat unorthodox, since there doesn't seem to be a true chorus section; the main verse alternates with a short, subdued break ... and after two cycles, the song builds to a completely different ending section."[57] The first portion is centered primarily around acoustic guitar and piano,[57] with a chord progression indebted to The Beatles' "Sexy Sadie".[3][58][59] Starting at 2:10, the song transitions into a more orchestrated section with the repeated line "Phew, for a minute there, I lost myself".[57] After this the song ends with Ed O'Brien playing guitar feedback[58] using an AMS digital delay pedal.[36] The title and lyrics to "Karma Police" originate from a band in-joke during The Bends tour. Jonny Greenwood said "whenever someone was behaving in a particularly shitty way, we'd say 'The karma police will catch up with him sooner or later.'"[41] Yorke said the song "is dedicated to everyone who works for a big firm. It's a song against bosses."[17]

Tracks 7-12

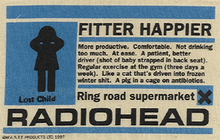

"Fitter Happier", which begins the second half of the album, consists of sampled musical and background sound and lyrics recited by a synthesised voice from the Macintosh SimpleText application.[60] Written after a period of writer's block, "Fitter Happier" was described by Yorke as a checklist of slogans for the 1990s, which he considered "the most upsetting thing I've ever written".[41][61]

"Electioneering", featuring cowbell and a distorted guitar solo, has been compared to the band's more rock-oriented style on their debut, Pablo Honey.[60][62] Yorke likened its lyrics, which focus on political and artistic compromise, to "a preacher ranting in front of a bank of microphones."[35][63]

The next track, "Climbing Up the Walls", is marked by ambient insect-like noises and "metallic" drums. The song's string section, composed by Jonny Greenwood and written for 16 instruments, was inspired by modern classical composer Krzysztof Penderecki's Threnody to the Victims of Hiroshima; Greenwood said of the song that "I got very excited at the prospect of doing string parts that didn't sound like 'Eleanor Rigby', which is what all string parts have sounded like for the past 30 years."[64] The song is about "the monster in the closet", with Yorke drawing on a brief job as an orderly in a mental hospital, and an article in The New York Times about serial killers, in writing it.[17]

"No Surprises", one of the album's most melodic tracks, is layered with electric guitar inspired by the Beach Boys "Wouldn't It Be Nice",[65] acoustic guitar, glockenspiel and vocal harmonies.[66] With "No Surprises", the band strove to replicate the atmosphere of Marvin Gaye's music and the 1968 Louis Armstrong recording of "What a Wonderful World".[17] The lyrics seem to portray a suicide or an unfulfilled life, and dissatisfaction with contemporary social and political order.[67]

"Lucky" depicts a man who survives an aeroplane crash in a lake and becomes a "superhero"; the song is thematically linked to "Airbag", and Yorke has described the song in interviews as having "positive", upbeat lyrics.[68] The track is similar to the early-1970s music of Pink Floyd, a major influence on Jonny Greenwood.[4]

The album ends with Jonny Greenwood's "The Tourist", which he wrote as an unusually staid piece where something "doesn't have to happen...every 3 seconds." He said, "'The Tourist' doesn't sound like Radiohead at all. It has become a song with space."[17] Yorke said it was chosen as the closing track song because, "a lot of the album was about background noise and everything moving too fast and not being able to keep up. It was really obvious to have 'Tourist' as the last song. That song was written to me from me, saying, 'Idiot, slow down.' Because at that point, I needed to. So that was the only resolution there could be: to slow down."[26]

Title and artwork

"OK Computer" was the original title for the song "Palo Alto", which had been considered for inclusion on the album.[69] Although the song was abandoned, its first title stuck with the band; according to Jonny Greenwood, "[it] started attaching itself and creating all these weird resonances with what we were trying to do."[32] Yorke said it "refers to embracing the future, it refers to being terrified of the future, of our future, of everyone else's. It's to do with standing in a room where all these appliances are going off and all these machines and computers and so on [...] and the sound it makes."[70] Yorke described the title as "a really resigned, terrified phrase", to him similar to the Coca-Cola advertisement "I'd Like to Teach the World to Sing".[32] Wired writer Leander Kahney suggests that it is an homage to Macintosh computers, as "The Mac's built-in speech recognition software responds to the command 'OK Computer,' as an alternative to hitting an OK button onscreen."[71] Other titles considered were Ones and Zeroes—a reference to the binary numeral system—and Your Home May Be at Risk If You Do Not Keep Up Payments.[69]

The album's artwork is a collage of images and text created by Stanley Donwood and Yorke, credited under the pseudonym "The White Chocolate Farm".[72] Donwood was commissioned by Yorke to work on the artwork alongside the recording sessions.[33] Yorke explained, "If I'm shown some kind of visual representation of the music, only then do I feel confident. Up until that point, I'm a bit of a whirlwind."[33] The colour palette is predominantly white and blue,[73], according to Donwood, the result of "trying to make something the color of bleached bone."[74] Used twice on the artwork, once in the booklet and once on the compact disc itself, is the image of two stick figures shaking hands. Yorke explained the image as emblematic of exploitation, saying, "Someone's being sold something they don't really want, and someone's being friendly because they're trying to sell something. That's what it means to me."[21] Explaining the artwork's themes, Yorke said, "It's quite sad, and quite funny as well. All the artwork and so on ... It was all the things that I hadn't said in the songs."[21]

Visual motifs in the artwork include motorways, aeroplanes, families with children, corporate logos and cityscapes.[75] The words "Lost Child" feature prominently on the cover, and the booklet artwork contains phrases in the constructed language Esperanto and health-related instructions in both English and Greek. The use of disconnected phrases led a critic for Uncut to say, "The non-sequiturs created an effect akin to being lifestyle-coached by a lunatic."[76] White scribbles, Donwood's method of correcting mistakes rather than using the computer function undo,[74] are present everywhere in the collages.[77] The liner notes contain the full lyrics, rendered with atypical syntax, alternate spelling[78] and small annotations; for example, the line "in a deep deep sleep of the innocent" from "Airbag" is shown as ">in a deep deep sssleep of tHe inno$ent/

completely terrified".[79] The lyrics are also arranged and spaced in shapes that resemble hidden images.[80] In keeping with the band's then emergent anti-corporate stance, the production credits contain the ironic copyright notice; "Lyrics reproduced by kind permission even though we wrote them."[81]Release and promotion

Selway admitted that when the band delivered the album, the band's American label Capitol saw "more or less, 'commercial suicide'. They weren't really into it. At that point, we got the fear. How is this going to be received?"[6] Capitol lowered its estimates from two million units to a half a million.[82] In O'Brien's view only Parlophone, the band's British label, was optimistic as global distributers dramatically reduced their sales estimates.[83] Label representatives were reportedly disappointed with the lack of potential marketable singles, especially the absence of anything resembling their initial hit, "Creep".[84]

The lyrics to "Fitter Happier" and images adapted from the album artwork were used on advertisements in music magazines, signs in the London Underground and shirts (shirt design pictured).

The lyrics to "Fitter Happier" and images adapted from the album artwork were used on advertisements in music magazines, signs in the London Underground and shirts (shirt design pictured).

Parlophone's advertising campaign was unorthodox. The label took full-page advertisements in high-profile British newspapers and tube stations with lyrics for "Fitter Happier" pitched in large black letters against white backgrounds.[6] The same lyrics, and artwork adapted from the album, were repurposed for shirt designs.[21] Yorke said, "We actively chose to pursue the 'Fitter Happier' thing" in linking what a critic called "a coherent set of concerns" between the album artwork and its promotional material.[21] More unconventional merchandise included a floppy disk with Radiohead screensavers and an FM radio in the shape of a desktop computer.[85] In America, Capitol sent 1,000 cassette players to prominent members of the press and music industry, each with a copy of the album permanently glued inside.[86] Capitol president Gary Gersh, when asked about the campaign after the album's release, said "Our job is just to take them as a left-of-center band and bring the center to them. That's our focus, and we won’t let up until they’re the biggest band in the world."[87]

OK Computer was released in Japan on 21 May, in the UK on 16 June and in the US on 1 July.[88] In addition to the dominant CD format, the album was released as a double-LP vinyl record, cassette and MiniDisc.[89] That month, Radiohead embarked on a world tour in promotion of OK Computer called the "Against Demons" tour.[90]

Radiohead chose "Paranoid Android" to be released as the lead single, despite being considered uncommercial for its unusually long running time and lack of a catchy chorus.[59][91] Colin Greenwood admitted the song was "hardly the radio-friendly, breakthrough, buzz bin unit shifter [radio stations] can have been expecting," but said that Capitol was supportive of the band's choice.[91] On the strength of frequent radio play on Radio 1[91] and rotation of the song's music video on MTV,[92] "Paranoid Android" reached number three in the U.K. giving Radiohead their highest chart position to date[93] and their highest overall as of 2011.[94] The album debuted at number one on the U.K., where it held for two weeks. It stayed in the top 10 for weeks and became the country's eighth-best selling record of the year.[95] When "Karma Police" and "No Surprises" were released as singles, both charted in the UK top 10; additionally, "Karma Police" peaked at number 14 on the Billboard Modern Rock Tracks chart.[94][96] "Lucky" was released as a promotional single in France but did not chart.[97] "Let Down", considered for release as the lead single,[55] charted on the Modern Rock Tracks chart at number 29.[96]

The band planned to produce a video for every song on the album to be released as a whole, but the project was abandoned due to financial and time constraints.[98] Also considered, but ultimately scrapped, were plans for trip hop group Massive Attack to remix the entire album.[99] Meeting People Is Easy, a rockumentary following the band on its OK Computer world tour, premiered in 1998.[100] By February 1998, the album had sold at least half a million copies in the UK and 2 million worldwide.[52] To date, at least 1.2 million copies have been sold in the US,[101] 3 million across Europe[102] and a total of 4.5 million worldwide.[101] OK Computer has been certified triple platinum in the UK,[103] double platinum in the US[104] and platinum in Australia.[105]

Critical reception

Upon its release, OK Computer received almost unanimously positive reviews. Consensus among critics was that the album was a landmark of its time and would have far-reaching impact and importance.[106][107] NME gave the album a ten out of ten score, and reviewer James Oldham wrote "Here are 12 tracks crammed with towering lyrical ambition and musical exploration; that refuse to retread the successful formulas of before and instead opt for innovation and surprise; and that vividly articulate both the dreams and anxieties of one man without ever considering sacrifice or surrender. In short, here is a landmark record of the 1990s, and one that deserves your attention more than any other released this year."[108] Taylor Parkes of Melody Maker connected the album's release to the era's feeling of paranoia and alienation about millenarianism, and said "It's as pained and as slow-moving as the emotions that inspired it. ... In one way or another, Radiohead have excelled themselves."[109] Q awarded the album five out of five stars, with writer David Cavanagh stating that "the majority of OK Computer's 12 songs ... takes place in a queer old landscape: unfamiliar and ominous, but also beautiful and unspoiled. ... It's a huge, mysterious album for the head and soul."[110] Nick Kent wrote in Mojo that "Others may end up selling more, but in 20 years time I'm betting OK Computer will be seen as the key record of 1997, the one to take rock forward instead of artfully revamping images and song-structures from an earlier era."[59] In a four-out-of-five-stars review, Caroline Sullivan of The Guardian wrote that the album "is surprising and sometimes inspiring but its intensity makes for a demanding listen."[111]

OK Computer was also favourably received by critics in North America. Rolling Stone gave the album four out of five stars. Reviewer Mark Kemp wrote that the album is "a stunning art-rock tour de force ... On OK Computer, Radiohead take the ideas they had begun toying with on The Bends into the stratosphere. ... OK Computer is evidence that [Radiohead] are one rock band still willing to look the devil square in the eyes", but warned "OK Computer is not an easy listen."[112] In a review scored at eight out of ten, Spin reviewer Barry Walters praised "the embattled musicianship, the tightly wound arrangements, the whacked out but tangible humanity" of the band's playing and Yorke's "vocal performance that radiates major drama without grandstanding", calling the album "an achievement few mainstream guitar bands can claim."[29] In an article for The New Yorker, writer Alex Ross praised OK Computer for its progressiveness, and contrasted Radiohead's risk-taking with the more musically conservative "dadrock" of their contemporaries Oasis. Ross wrote that "Throughout the album, contrasts of mood and style are extreme [...] This band has pulled off one of the great art-pop balancing acts in the history of rock."[113] Ryan Schreiber wrote, in a highly enthusiastic review in his online music magazine Pitchfork Media, that "Radiohead's third piece of incredible work, OK Computer, is not only their best yet, but one of the year's greatest releases. The record is brimming with genuine emotion, beautiful and complex imagery and music, and lyrics that are at once passive and fire-breathing."[114]

Some reviews were mixed or contained qualified praise. Robert Christgau of The Village Voice gave OK Computer a B− rating and ranked it as the "Dud of the Month" in his consumer guide. Christgau commented that the album lacked "soul", calling it "arid" and "ridiculous", and compared it unfavourably to Pink Floyd.[115] An Entertainment Weekly review by David Browne gave the album a B+, and wrote that "When the arrangements and lyrics meander or sprout pretensions, the album grows ponderous and soggy. For all of Radiohead's growing pains, though, their aim — to take British pop to a heavenly new level — is true."[116] Andy Gill wrote for The Independent in an otherwise positive review, "For all its ambition, OK Computer is not, finally, as impressive as The Bends, which covered much the same sort of emotional knots, but with better tunes. It is easy to be impressed by, but ultimately hard to love, an album that so luxuriates in its despondency."[117] While a review in Time was largely positive, particularly praising the songs "Airbag", "Paranoid Android", and "Let Down", reviewer Christopher John Farley criticised the second half of the album. Farley said, "While the first half-dozen tracks reward repeated listenings with melodies that grow and bloom with familiarity, there is often no structure to be found in the remaining half-dozen numbers."[118] Greg Kot, writing for the Chicago Tribune, gave the album three and a half stars and said, "Long gone is the concise neo-grunge of the group's breakthrough single, "Creep." In its place are serpentine arrangements, psychedelic orchestrations and haunting melodies that belie the wretchedness detailed in the lyrics. ... Rarely has a tantrum sounded so seductive."[119]

The nearly universally positive reception to the album overwhelmed the band, and some members thought the press was excessively congratulatory. Particularly irksome to the band were comparisons to progressive rock and "art rock", with Yorke saying "We write pop songs ... there was no intention of it being 'art'. It's a reflection of all the disparate things we were listening to when we recorded it."[70] Yorke was nevertheless pleasantly surprised that many listeners identified some of the album's musical influences, saying "What really blew my head off was the fact that people got all the things, all the textures and the sounds and the atmospheres we were trying to create."[120] Jonny Greenwood responded to the album's reception by saying "In England, I think a lot of the reviews have been slightly over-the-top, because the last album [The Bends] was somewhat under-reviewed possibly and under-received."[26]

Legacy

Retrospective acclaim

OK Computer appeared in many 1997 critics' lists and listener polls for best album of the year. It topped the year-end polls of Mojo, Vox, Entertainment Weekly, Hot Press, Muziekkrant OOR, HUMO, Eye Weekly and Inpress, and tied for first place with Daft Punk's Homework in The Face. The album came second in NME, Melody Maker, Rolling Stone, Village Voice, Spin and Uncut. Q and Les Inrockuptibles both listed the album in their unranked year-end polls.[121] It was a nominee for the 1997 Mercury Prize, a prestigious award recognising the best British or Irish album of the year.[122] The album was nominated in the Album of the Year and Best Alternative Music Performance categories at the 1998 Grammy Awards, ultimately winning the latter.[123]

OK Computer has appeared frequently in professional lists of greatest albums. A number of publications, including NME, Melody Maker, Alternative Press,[124] Spin,[125] Pitchfork,[126] Time[127] and Slant[128] placed OK Computer prominently in lists of best albums of the 1990s or of all time. In 2003, the album was ranked number 162 on Rolling Stone magazine's list of the 500 greatest albums of all time.[129] Retrospective reviews from BBC Music,[130] The A.V. Club[131] Slant[132] and Paste[133] have received the album favourably; likewise, Rolling Stone gave the album five stars in the 2004 Rolling Stone Album Guide, with critic Rob Sheffield saying "Radiohead was claiming the high ground abandoned by Nirvana, Pearl Jam, U2, R.E.M., everybody; and fans around the world loved them for trying too hard at a time when nobody else was even bothering."[134]

OK Computer has been cited by some as undeserving of its acclaim, while others assert that Radiohead's career was negatively impacted by the album's critical success. In a poll surveying thousands conducted by BBC 6 Music, OK Computer was named the sixth most overrated album "in the world".[135] David H. Green of The Daily Telegraph called the album "self-indulgent whingeing" and maintains that the positive critical consensus toward OK Computer is an indication of "a 20th-century delusion that rock is the bastion of serious commentary on popular music" to the detriment of electronic and dance music.[136] The album was selected as an entry in "Sacred Cows", an NME column questioning the critical status of "revered albums", in which Henry Yates said of the album "There’s no defiance, gallows humour or chink of light beneath the curtain, just a sense of meek, resigned despondency," and further criticized the record as "the moment when Radiohead stopped being 'good' [compared to The Bends] and started being 'important'."[137] In a Spin article on the "myth" that "Radiohead Can Do No Wrong", Chris Norris argues that the acclaim for OK Computer created an inflated set of expectations for each successive Radiohead release.[138]

Cultural response

In interviews, Thom Yorke criticized recently elected Tony Blair (pictured in 1998) and his "New Labour" government. Critics have interpreted undertones of political dissatisfaction in the music and lyrics on OK Computer.

In interviews, Thom Yorke criticized recently elected Tony Blair (pictured in 1998) and his "New Labour" government. Critics have interpreted undertones of political dissatisfaction in the music and lyrics on OK Computer.

OK Computer was recorded in the lead up to the 1997 general election. It was thus seen by critics as encompassing public opinion through its "despairing-yet-hopeful tone" and themes of alienation.[130] Yorke said in an interview that his lyrics had been affected by reading a book about the two decades of Conservative government which were just coming to an end in 1997, as well as about factory farming and globalisation. However, Yorke expressed little hope things would change under the corporate-controlled "New Labour" government of Tony Blair.[21] David Stubbs said that, where punk rock had been a rebellion against a time of deficit and poverty, OK Computer protested the "mechanistic convenience" of contemporary surplus and excess.[139] Jon Pareles of The New York Times found precedents in Radiohead's concerns "about a culture of numbness, building docile workers and enforced by self-help regimes and anti-depressants" in the work of Pink Floyd and Madness.[140] The band's distaste with the commercialized promotion of OK Computer reinforced their anti-capitalist political viewpoint, which would be further explored on their subsequent releases.[141]

With the year 2000 approaching, many felt the tone of the album was millennial[142] or futuristic.[143] According to The A.V. Club writer Steven Hyden in the feature "Whatever Happened to Alternative Nation", "Radiohead appeared to be ahead of the curve, forecasting the paranoia, media-driven insanity, and omnipresent sense of impending doom that’s subsequently come to characterize everyday life in the 21st century."[144] In 1000 Recordings to Hear Before You Die, Tom Moon described OK Computer as a "prescient ... dystopian essay on the darker implications of technology ... oozing [with] a vague sense of dread, and a touch of Big Brother foreboding that bears strong resemblance to the constant disquiet of life on Security Level Orange, post-9/11."[145] Chris Martin of Coldplay remarked that, "It would be interesting to see how the world would be different if Dick Cheney really listened to Radiohead's OK Computer. I think the world would probably improve. That album is fucking brilliant. It changed my life, so why wouldn't it change his?"[146]

Musical influence

"OK Computer is Radiohead really stretching and pushing the boundaries of what they think they're capable of doing and what their audience think they're capable of doing and it is a classic, brilliant record."

"OK Computer is pretty much a landmark record. As time goes on and we get away from when it was released, more and more it would be seen as the important record it is."

"The whole sound of it and the emotional experience crossed a lot of boundaries. It tapped into a lot of buried emotions that people hadn't wanted to explore or talk about."

The release of OK Computer coincided with the decline of Britpop.[130] Britpop, which reached its peak popularity in the mid-1990s and was led by bands such as Oasis and Blur, typically emphasized traditionalist homage to British rock of the 1960s and 1970s. The genre was a key element of the broader cultural movement Cool Britannia. Starting in 1997, a number of events marked the end of the genre's heyday; these included Blur spurning the conventional Britpop sound on Blur and Oasis' Be Here Now failing to live up to audience expectations.[148] Through OK Computer's influence, the dominant style of UK guitar pop shifted toward an approximation of "Radiohead's paranoid but confessional, slurry but catchy approach".[149] Many newer British acts used similarly complex, atmospheric arrangements. "Post-Britpop" band Travis worked with Godrich to create the languid pop texture of The Man Who, which became the biggest-selling album of 1999 in the UK.[150] Some in the British press accused Travis of appropriating Radiohead's sound.[151]

John Harris writes that OK Computer was among several "fleeting signs that British rock music might [have been] returning to its inventive traditions" in the wake of Britpop's demise.[152] However, Footman says the "Radiohead Lite" bands that followed were "missing [OK Computer's] sonic inventiveness, not to mention the lyrical substance".[153] Radiohead described the prevalence of bands that "sound like us" as one reason to break with the style of OK Computer for their next album, Kid A.[154] When asked by MTV interviewer Gideon Yago what the band thought of "bands like Travis, Coldplay, and Muse ... making a career sounding exactly like [Radiohead] did in 1997", Yorke replied "Good luck with Kid A!"[155] While Harris concludes that British rock ultimately developed an "altogether more conservative tendency", he says that with OK Computer and their subsequent material, Radiohead provided a "clarion call" to fill the void left by Britpop.[152]

OK Computer triggered a minor revival of progressive rock and ambitious concept albums, paving the way for prog-influenced bands such as Dungen, Mew, Mystery Jets, The Secret Machines and Pure Reason Revolution. Brandon Curtis of The Secret Machines said "Songs like 'Paranoid Android' made it OK to write music differently, to be more experimental. OK Computer was important because it reintroduced unconventional writing and song structures."[156] However, the band has rejected any affiliation with the genre and denies having attempted to make a coherent concept album.[70] Jonny Greenwood dismissed such claims by saying "I think one album title and one computer voice do not make a concept album. That's a bit of a red herring."[70]

Several rock bands which later became popular, including Coldplay,[146][157] Bloc Party[158] and TV on the Radio,[159] have said they were formatively influenced by OK Computer—TV on the Radio's debut album, for instance, was titled OK Calculator. Additionally, the album's popularity paved the way for British alternative rock bands such as Muse, Snow Patrol, Keane,[157] Travis, Doves, Badly Drawn Boy,[160] Editors and Elbow.[161] Established musicians such as R.E.M. frontman Michael Stipe, former Smiths guitarist Johnny Marr,[147] Mo' Wax label owner James Lavelle[125] and Depeche Mode and Recoil member Alan Wilder[162] are fans of the album. Classical and jazz musicians such as Christopher O'Riley and Brad Mehldau have performed material from OK Computer, and composer Esa-Pekka Salonen said "When I heard OK Computer, after five minutes I said, 'I actually get this. I understand what these people are trying to do.' And what they were trying was not so drastically different from what I was trying to do."[163]

Reissues

Radiohead left EMI, parent company of Parlophone, in 2007 after failed contract negotiations. EMI retained the copyright to Radiohead's back catalogue of material recorded while signed to the label.[164] After a period of being out of print on vinyl, EMI reissued a double-LP of OK Computer on 19 August 2008, along with later albums Kid A, Amnesiac and Hail to the Thief as part of the "From the Capitol Vaults" series.[165] OK Computer became the year's tenth best-selling vinyl record, shifting just under 10,000 units.[166] The reissue was connected in the press to a general upswing in vinyl sales and cultural appreciation of records as a format.[166][167][168][169]

OK Computer was reissued again on 24 March 2009 simultaneously with Pablo Honey and The Bends, without Radiohead's involvement. The reissue came in two editions: a 2-CD "Collector's Edition" and a 2-CD 1-DVD "Special Collector's Edition". The first disc contains the original studio album, the second disc contains B-sides collected from OK Computer singles and live recording sessions, and the DVD contains a collection of music videos and a live television performance.[170] All material on the reissue had been previously released[74] and the music was not remastered.[171]

In a March 2009 interview, O'Brien claimed that EMI had not notified the band members of the reissue and said "I think the fans have got most of [the material on the reissues], it's all the stuff up on YouTube. This is just a company who are trying to squeeze every bit of lost money, it's not about [an] artistic statement."[172] Press reaction to the reissue announcement reflected the concern that EMI was exploiting Radiohead's back catalogue. Larry Fitzmaurice of Spin accused EMI of planning to "issue and re-issue [Radiohead's] discography until the cash stops rolling in",[170] and Pitchfork's Ryan Dombal said it was "hard to look at these reissues as anything other than a cash-grab for EMI/Capitol—an old media company that got dumped by their most forward-thinking band."[74] Daniel Kreps of Rolling Stone defended EMI, saying "While it's easy to accuse Capitol of milking the cash cow once again, these sets are pretty comprehensive."[173]

Reception to the reissue was mixed, especially regarding the value of the bonus material. A Pitchfork review written by Scott Plagenhoef awarded the reissue a perfect score, arguing that it was worth buying for fans who did not already own the rare material. Plagenhoef said, "That the band had nothing to do with these is beside the point: This is the final word on these records, if for no other reason that the Beatles' September 9 remaster campaign is, arguably, the end of the CD era."[174] Stephen Thomas Erlewine of Allmusic said that "While none of this material is bad—and much is quite good—this isn't a disc that's necessary to the appreciation of OK Computer. It's not revelatory; it's a good set of footnotes carrying some mildly interesting supplemental material."[175] Sam Richards of Uncut praised the bonus disc material for providing "fresh angles" on Radiohead's sound, but called the accompanying DVD "flimsy" and said it was a "shame" that EMI did not acquire footage of Radiohead's "legendary 1997 Glastonbury performance".[161]

Will Hermes said in his review for Rolling Stone that while the reissue demonstrates that the "cream" of the band's output was on the original album, the bonus tracks better foreshadow the sound of Radiohead's later material.[176] PopMatters included the release in its list of the best reissues of the year, but criticized the "inexcusable" absence of expanded liner notes; Sean McCarthy wrote "at least Capitol could have hired a few notable critics to write about the enormous impact" of the album.[171] The A.V. Club writer Josh Modell praised both the bonus disc and the DVD, and said of the album, "And what can be said about 1997’s OK Computer that hasn’t been said before? It really is the perfect synthesis of Radiohead’s seemingly conflicted impulses."[177]

Track listing

All songs written by Thom Yorke, Jonny Greenwood, Ed O'Brien, Colin Greenwood and Phil Selway, except where noted.

- "Airbag" – 4:44

- "Paranoid Android" – 6:23

- "Subterranean Homesick Alien" – 4:27

- "Exit Music (For a Film)" – 4:24

- "Let Down" – 4:59

- "Karma Police" – 4:21

- "Fitter Happier" – 1:57

- "Electioneering" – 3:50

- "Climbing Up the Walls" – 4:45

- "No Surprises" – 3:48

- "Lucky" – 4:19

- "The Tourist" – 5:24

"Collector's Edition" disc 2

- "Paranoid Android" B-sides

- "Polyethylene (Parts 1 & 2)" – 4:23

- "Pearly*" – 3:37

- "A Reminder" – 3:53

- "Melatonin" (Thom Yorke) – 2:09

- "Karma Police" B-sides

- "Meeting in the Aisle" – 3:09

- "Lull" – 2:29

- "Climbing Up the Walls" (Zero 7 mix) – 5:19

- "Climbing Up the Walls" (Fila Brazillia mix) – 6:25

- "No Surprises" B-sides

- "Palo Alto" – 3:44

- "How I Made My Millions" – 3:09

- "Airbag" (Live in Berlin) – 4:49

- "Lucky" (Live in Florence) – 4:36

- BBC Radio One Evening Session (28 May 1997)

- "Climbing Up the Walls" – 4:20

- "Exit Music (For a Film)" – 4:35

- "No Surprises" – 3:58

"Special Collector's Edition" DVD

- Music videos

- "Paranoid Android"

- "Karma Police"

- "No Surprises"

- Later... with Jools Holland live performance (31 May 1997)

- "Paranoid Android"

- "No Surprises"

- "Airbag"

Personnel

- Radiohead

- Thom Yorke – vocals, guitar, piano, laptop

- Jonny Greenwood – guitar, keyboards, piano, organ, glockenspiel, string arrangements

- Ed O'Brien – guitar, backing vocals

- Colin Greenwood – bass guitar, keyboards

- Phil Selway – drums

- Additional personnel

- Nigel Godrich – production, engineering

- Jim Warren – production, engineering

- Chris Blair – mastering

- Stanley Donwood and "The White Chocolate Farm" – illustrations

- Nick Ingman – conducting

Charts

Album

Chart (1997) Peak

positionAustralian Albums Chart[178] 7 Austrian Albums Chart[179] 17 Belgian Albums Chart (Flanders)[180] 1 Belgian Albums Chart (Wallonia)[180] 3 Canadian Albums Chart[181] 3 Dutch Albums Chart[182] 2 French Albums Chart[183] 3 German Albums Chart[184] 27 New Zealand Albums Chart[185] 1 Spanish Albums Chart[186] 42 Swedish Albums Chart[187] 3 Swiss Albums Chart[188] 40 UK Albums Chart[94] 1 US Billboard 200[189] 21 Singles

Year Song Peak positions UK

[94]US Modern Rock

[96]NZ

[190]AUS

[191]SWE

[192]NL

[193]1997 "Paranoid Android" 3 — — 29 53 61 1997 "Karma Police" 8 14 32 — — 50 1998 "No Surprises" 4 — 23 47 — 58 "—" denotes releases that did not chart. References

- Footnotes

- ^ Footman 2007, p. 113.

- ^ a b c d e f g Irvin, Jim (July 1997), "Thom Yorke tells Jim Irvin how OK Computer was done", Mojo

- ^ a b c Lowe, Steve (December 1999), "Back to Save the Universe", Select

- ^ a b Randall 2000, p. 161.

- ^ Footman 2007, p. 33.

- ^ a b c Cantin, Paul (19 October 1997), "Radiohead's OK Computer confounds expectations", Ottawa Sun

- ^ Richardson, Andy (9 December 1995), "Boom! Shake the Gloom!", NME

- ^ Footman 2007, p. 34.

- ^ Randall 2000, p. 189.

- ^ a b Glover, Arian (1 August 1998), "Radiohead—Getting More Respect.", Circus

- ^ a b Randall 2000, pp. 190–191.

- ^ Beauvallet, JD (25 January 2000), "Nigel the Nihilist", Les Inrockuptibles

- ^ Randall 2000, p. 194.

- ^ Randall 2000, p. 195.

- ^ Footman 2007, p. 25.

- ^ "Thom Yorke loves to skank", Q, 12 August 2002

- ^ a b c d e "Radiohead: The Album, Song by Song, of the Year", HUMO, 22 July 1997

- ^ Footman 2007, p. 67.

- ^ Randall 2000, p. 196.

- ^ Footman 2007, p. 35.

- ^ a b c d e f g Harris, John (January 1998), "Renaissance Men", Select

- ^ a b Vaziri, Aidin (October 1997), "British Pop Aesthetes", Guitar Player

- ^ Randall 2000, p. 198.

- ^ Randall 2000, p. 199.

- ^ Randall 2000, p. 200.

- ^ a b c d DiMartino, Dave (2 May 1997), "Give Radiohead Your Computer", LAUNCH, archived from the original on 14 August 2007, http://web.archive.org/web/20070814183856/http://music.yahoo.com/read/interview/12048024, retrieved 2 June 2009

- ^ a b c Sutcliffe, Phil (October 1999), "Radiohead: An Interview With Thom Yorke", Q

- ^ a b Bailie, Stuart (21 June 1997), "Viva la Megabytes!", NME

- ^ a b Walters, Barry (August 1997), "Radiohead: OK Computer: Capitol", Spin: 112–113

- ^ Sutherland, Mark (24 May 1997), "Rounding the Bends", Melody Maker

- ^ a b Sutcliffe, Phil (1 October 1997), "Death is all around", Q

- ^ a b c Sakamoto, John (2 June 1997), "Radiohead talk about their new video", Jam!

- ^ a b c Lynskey, Dorian (February 2011), "Welcome to the Machine", Q: 82–85

- ^ Footman 2007, pp. 142-150.

- ^ a b c Wadsworth, Tony (20 December 1997), "The Making of OK Computer", The Guardian

- ^ a b c Randall, Mac (1 April 1998). "Radiohead interview: The Golden Age of Radiohead". p. 4. Archived from the original on 05 August 2011. http://www.webcitation.org/60imxcDom. Retrieved 5 August 2011.

- ^ Footman 2007, p. 42.

- ^ Randall 2000, pp. 213–214.

- ^ Footman 2007, pp. 44-45.

- ^ Randall 2000, pp. 214–215.

- ^ a b c d e f Sutherland, Mark (31 May 1997), "Return of the Mac!", Melody Maker

- ^ Jabba (February 1998). "Interview with Colin Greenwood". Channel V.

- ^ Footman 2007, p. 62.

- ^ Footman 2007, pp. 60-61.

- ^ Footman 2007, pp. 59-60.

- ^ Appleford, Steve (January-February 1998), "Under Pressure: Just What Do You Want From Radiohead?", Option

- ^ Footman 2007, p. 65.

- ^ Footman 67.

- ^ Randall 2000, p. 154.

- ^ a b Footman 66.

- ^ Wylie, Harry (November 1997), "Radiohead", Total Guitar

- ^ a b "The 100 Greatest Albums in the Universe", Q, February 1998

- ^ Dalton, Stephen (September 1997), "The Dour & The Glory", Vox

- ^ Footman 2007, p. 73.

- ^ a b Footman 2007, p. 74.

- ^ Gaitskill, Mary (April 1998), "Radiohead: Alarms and Surprises", Alternative Press

- ^ a b c Huey, Steve, "Karma Police", AllMusic, archived from the original on 10 December 2010, http://web.archive.org/web/20101210235903/http://allmusic.com/song/karma-police-t1416670, retrieved 13 October 2008

- ^ a b Footman 2007, p. 79.

- ^ a b c Kent, Nick (July 1997), "Press your space next to mine, love", Mojo

- ^ a b Randall 2000, pp. 158–159.

- ^ Randall 2000, pp. 224–225.

- ^ Footman 2007, pp. 93-94.

- ^ Randall 2000, p. 226.

- ^ Footman 2007, pp. 99-102.

- ^ Footman 2007, p. 110.

- ^ Bill, Janovitz, "No Surprises", AllMusic, archived from the original on 10 December 2010, http://web.archive.org/web/20101210230041/http://allmusic.com/song/no-surprises-t1416673, retrieved 18 October 2008

- ^ Footman 2007, pp. 108-109.

- ^ Randall 2000, p. 230.

- ^ a b Footman 2007, pp. 36–37.

- ^ a b c d Clarke 2010, p. 124.

- ^ Kahney, Leander (1 February 2002), "He Writes the Songs: Mac Songs", Wired, archived from the original on 26 August 2011, http://www.webcitation.org/61EowCFPD, retrieved 26 August 2011

- ^ Krüger, Sascha (July 2008), "Exit Music" (in German), Visions

- ^ Griffiths 2004, p. 79.

- ^ a b c d Dombal, Ryan (15 September 2010), "Take Cover: Radiohead Artist Stanley Donwood", Pitchfork Media, archived from the original on 19 September 2011, http://www.webcitation.org/61pgKUYvb, retrieved 19 September 2011

- ^ Footman 2007, pp. 127–130.

- ^ Cavanagh, David (February 2007), "Communication Breakdown", Uncut

- ^ Griffiths 2004, p. 81.

- ^ Kuipers, Dean (March 1998), "Fridge Buzz Now", Ray Gun

- ^ Footman 2007, pp. 45.

- ^ Arminio, Mark (26 June 2009), "Between the Liner Notes: 6 Things You Can Learn By Obsessing Over Album Artwork", Mental floss, archived from the original on 26 August 2011, http://www.webcitation.org/61EhZg91r, retrieved 26 August 2011

- ^ Odell, Michael (September 2003), "Inside the Mind of Radiohead's Mad Genius!", Blender

- ^ Randall 2000, p. 202.

- ^ Randall 2000, p. 242.

- ^ Blashill, Pat (January 1998), "Band of the Year: Radiohead", Spin: 64–67

- ^ Martins, Chris (29 March 2011). "Radiohead Gives Out Free Newspaper in LA: Here's a Top Eight List of the Band's Most Peculiar Swag". p. 2. Archived from the original on 30 September 2011. http://www.webcitation.org/625T4qiY1. Retrieved 30 September 2011.

- ^ Randall 2000, p. 243.

- ^ Hoskyns, Barney (October 2000), "Exit Music: Can Radiohead save rock music as we (don’t) know it?", GQ

- ^ Footman 2007, p. 38.

- ^ Footman 2007, p. 126.

- ^ Clarke 2010, pp. 202–203.

- ^ a b c Sutherland, Mark (4 March 1998), "Rounding the Bends", Melody Maker

- ^ Gulla, Bob (October 1997), "Radiohead: At Long Last, a Future for Rock Guitar", Guitar World

- ^ Randall 2000, pp. 242–243.

- ^ a b c d "everyHit.com - UK Top 40 Chart Archive, British Singles & Album Charts". http://www.everyhit.com/. Retrieved 30 September 2008.

- ^ Randall 2000, p. 247.

- ^ a b c "Artist Chart History - Radiohead". Billboard. Archived from the original on 16 June 2009. http://web.archive.org/web/20090616164309/http://www.billboard.com/bbcom/retrieve_chart_history.do?model.vnuArtistId=33472&model.vnuAlbumId=1089621. Retrieved 30 September 2008.

- ^ Footman 2007, p. 116.

- ^ Clarke 2010, p. 113.

- ^ "Massive Attack Drops Plans To Remix Radiohead, Teams With Cocteau Twins". MTV.com. 4 March 1998. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. http://www.webcitation.org/621Qgc6EE. Retrieved 27 September 2011.

- ^ Clarke 2010, p. 134.

- ^ a b Sexton, Paul (16 September 2000), "Radiohead won't play by rules", Billboard: 5

- ^ "James Blunt album sales pass 5m". BBC News Online. 8 April 2006. Archived from the original on 10 August 2011. http://www.webcitation.org/60qSY2B1U. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- ^ "Radiohead memorabilia goes under the hammer", Oxford Mail, 17 June 2009, archived from the original on 5 August 2011, http://www.webcitation.org/60ixyQ1Nc, retrieved 2 July 2011

- ^ "Gold and Platinum Database Search". RIAA. http://www.riaa.com/goldandplatinumdata.php. Retrieved 28 September 2008.

- ^ "ARIA Charts - Accreditations - 1998 Albums". ARIA. Archived from the original on 5 August 2011. http://www.webcitation.org/60izgulVU. Retrieved 5 August 2011.

- ^ Footman 2007, pp. 181-182.

- ^ Clarke 2010, p. 121.

- ^ Oldham, James (14 June 1997), "The Rise and Rise of the ROM Empire", NME

- ^ Parkes, Taylor (14 June 1997), "Review of OK Computer", Melody Maker

- ^ Cavanagh, David (July 1997), "Moonstruck", Q

- ^ Sullivan, Caroline (13 June 1997), "Aching Heads", The Guardian

- ^ Kemp, Mark (10 July 1997), "OK Computer : Radiohead : Review", Rolling Stone, http://www.rollingstone.com/music/albumreviews/ok-computer-19970710, retrieved 29 September 2008

- ^ Ross, Alex (29 September 1997), "Dadrock: Revisiting the Sixties with Oasis and Radiohead", The New Yorker: 88, http://www.newyorker.com/archive/1997/09/29/1997_09_29_088_TNY_CARDS_000378726, retrieved 29 September 2008

- ^ Schreiber, Ryan (31 December 1997), "Radiohead: OK Computer: Pitchfork Review", Pitchfork Media, archived from the original on 30 October 2001, http://web.archive.org/web/20010303103405/www.pitchforkmedia.com/record-reviews/r/radiohead/ok-computer.shtml, retrieved 16 May 2009

- ^ Christgau, Robert (23 September 1997), "Consumer Guide Sept. 1997", The Village Voice, archived from the original on 5 August 2011, http://www.webcitation.org/60j0hhTxA, retrieved 5 August 2011

- ^ Browne, David (11 July 1997), "OK Computer Review", Entertainment Weekly, archived from the original on 5 August 2011, http://www.webcitation.org/60j02Y2ke, retrieved 5 August 2011

- ^ Gill, Andy (13 June 1997), "First Impression: 'OK Computer' by Radiohead", The Independent, archived from the original on 12 October 2007, http://web.archive.org/web/20071012144627/http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_qn4158/is_20050429/ai_n14605169, retrieved 2 June 2009

- ^ Farley, Christopher John (25 August 1997), "Lost in Space", Time, archived from the original on 5 August 2011, http://www.webcitation.org/60j9j1Rrw, retrieved 11 October 2008

- ^ Kot, Greg (4 July 1997), "Radiohead OK Computer (Capitol)", Chicago Tribune, archived from the original on 30 September 2011, http://www.webcitation.org/625jfGwvc, retrieved 30 September 2011

- ^ Gill, Andy (5 October 2007), "Ok computer: Why the record industry is terrified of Radiohead's new album", The Independent, archived from the original on 5 August 2011, http://www.webcitation.org/60j0H2Z9t, retrieved 5 August 2011

- ^ Footman 2007, pp. 183-184.

- ^ "Mercury Prize 2008: The nominees". BBC News Online. 22 July 2008. Archived from the original on 5 August 2011. http://www.webcitation.org/60j3jj3kL. Retrieved 28 September 2008.

- ^ Randall 2000, p. 251, 255.

- ^ Footman 2007, p. 185.

- ^ a b c Smith, RJ (September 1999), "09: Radiohead: OK Computer", Spin: 122–123

- ^ DiCrescenzo, Brent (17 November 2003), "Top 100 Albums of the 1990s", Pitchfork Media, archived from the original on 22 June 2009, http://web.archive.org/web/20090622023306/http://pitchfork.com/features/staff-lists/5923-top-100-albums-of-the-1990s/10/, retrieved 2 June 2009

- ^ Tyrangiel, Josh (2 November 2006), "OK Computer - The ALL-TIME 100 Albums", Time, archived from the original on 5 August 2011, http://www.webcitation.org/60jAEuqVb, retrieved 5 August 2011

- ^ "Best Albums of the '90s". 14 February 2011. Archived from the original on 5 August 2011. http://www.webcitation.org/60jCbwEwZ. Retrieved 5 August 2011.

- ^ "162 OK Computer - Radiohead". 2004. Archived from the original on 5 August 2011. http://www.webcitation.org/60jBI6KG9. Retrieved 5 August 2011.

- ^ a b c Lusk, Jon (5 August 2011). "Radiohead: OK Computer". BBC. Archived from the original on 5 August 2011. http://www.webcitation.org/60jCnyTH7. Retrieved 23 May 2007.

- ^ Thompson, Stephen (29 March 2002), "Radiohead: OK Computer", The A.V. Club, archived from the original on 5 August 2011, http://www.webcitation.org/60jBOpl1v, retrieved 5 August 2011

- ^ Cinquemani, Sal (27 March 2007), "Radiohead: OK Computer", Slant, archived from the original on 5 August 2011, http://www.webcitation.org/60jBikMR8, retrieved 5 August 2011

- ^ Kemp, Mark (27 March 2009), "Radiohead: Pablo Honey, The Bends, OK Computer (reissues)", Paste, archived from the original on 29 August 2011, http://www.webcitation.org/61JEAzSsm, retrieved 29 August 2011

- ^ Brackett, Nathan; Hoard, Christian (2 November 2004), Rolling Stone Album Guide, New York City: Fireside, p. 671, ISBN 0-7432-0169-8

- ^ "Most Overrated Album in the World". BBC 6 Music. October 2005. Archived from the original on 9 August 2011. http://www.webcitation.org/60owcdZtT. Retrieved 9 August 2011.

- ^ Green, David H. (18 March 2009). "OK Computer Box Set: Not OK Computer". Archived from the original on 9 August 2011. http://www.webcitation.org/60owfm5xG. Retrieved 9 August 2011.

- ^ Yates, Henry (3 April 2011). "Sacred Cows - Is Radiohead's 'OK Computer' Overrated?". Archived from the original on 9 August 2011. http://www.webcitation.org/60owZfdWF. Retrieved 9 August 2011.

- ^ Norris, Chris (9 November 2009). "Myth No. 1: Radiohead Can Do No Wrong". Archived from the original on 10 August 2011. http://www.webcitation.org/60qD8YzED. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- ^ Radiohead: OK Computer - A Classic Album Under Review (DVD). Sexy Intellectual. 10 October 2006.

- ^ Pareles, Jon (28 August 1997). "Miserable and Loving It: It's Just So Very Good to Feel So Very, Very Bad". Archived from the original on 7 September 2011. http://www.webcitation.org/61WxbrsbL. Retrieved 7 September 2011.

- ^ Clarke 2010, p. 142.

- ^ "Is OK Computer the Greatest Album of the 1990s?", Uncut, 1 January 2007, archived from the original on 5 August 2011, http://www.webcitation.org/60jD6Jrug, retrieved 30 September 2008

- ^ Dwyer, Michael (14 March 1998), "OK Kangaroo", Melody Maker

- ^ Hyden, Steven (25 January 2011), "Whatever Happened to Alternative Nation? Part 8: 1997: The ballad of Oasis and Radiohead", The A.V. Club, archived from the original on 7 August 2011, http://www.webcitation.org/60lsruJcu, retrieved 7 August 2011

- ^ Moon 2008, pp. 627–628.

- ^ a b McLean, Craig (27 May 2005), "The importance of being earnest", The Guardian, archived from the original on 30 September 2011, http://www.webcitation.org/625ArFdCw, retrieved 30 September 2011

- ^ a b c Tapper, James (17 April 2005), "Radiohead's album best of all time - OK?", Daily Mail, archived from the original on 10 August 2011, http://www.webcitation.org/60qPsXaAx, retrieved 10 August 2011

- ^ Footman 2007, pp. 177–178.

- ^ "The 50 Greatest Bands: 15", Spin: 68, February 2002

- ^ Gulla, Bob (April 2000), "A Marriage Made in Song", College Music Journal

- ^ Sullivan, Kate (May 2000), "Travis", Spin: 62

- ^ a b Harris 2004, p. 369.

- ^ Footman, p. 219.

- ^ Murphy, Peter (11 October 2001), "How I learned to stop worrying and loathe the bomb", Hot Press, archived from the original on 5 August 2011, http://www.webcitation.org/60jDXlbkf, retrieved 5 August 2011

- ^ Ross, Alex (20 August 2001), "The Searchers: Radiohead's unquiet revolution", The New Yorker

- ^ Allen, Matt (14 June 2007), "Prog's progeny", The Guardian, archived from the original on 5 August 2011, http://www.webcitation.org/60jDNMrnd, retrieved 5 August 2011

- ^ a b Aza, Bharat (15 June 2007), "Ten years of OK Computer and what have we got?", The Guardian, archived from the original on 5 August 2011, http://www.webcitation.org/60jE5qiBg, retrieved 5 August 2011

- ^ Nunn, Adie (4 December 2003), "Introducing Bloc Party", Drowned in Sound, http://drownedinsound.com/in_depth/8568-introducing-bloc-party, retrieved 2 June 2009

- ^ Harrington, Richard (13 April 2007), "TV on the Radio: Coming in Loud and Clear", Washington Post: WE06, archived from the original on 5 August 2011, http://www.webcitation.org/60jEX6jr3, retrieved 30 September 2008

- ^ Eisenbeis, Hans (July 2001), "The Empire Strikes Back", Spin: 102–104

- ^ a b Richards, Sam (8 April 2009), "Album review: Radiohead Reissues - Collectors Editions", Uncut, archived from the original on 29 August 2011, http://www.webcitation.org/61JJm67dr, retrieved 29 August 2011

- ^ Turner, Luke (9 May 2011), "Alan Wilder Of Recoil & Depeche Mode's 13 Favourite LPs - Page 8", The Quietus, archived from the original on 6 September 2011, http://www.webcitation.org/61VQGlUlk, retrieved 6 September 2011

- ^ Timberg, Scott (28 January 2003), "The maestro rocks", Los Angeles Times, archived from the original on 5 August 2011, http://www.webcitation.org/60jEeH0tI, retrieved 5 August 2011

- ^ Sherwin, Adam (28 December 2007), "EMI accuses Radiohead after group’s demands for more fell on deaf ears", The Times, archived from the original on 29 August 2011, http://www.webcitation.org/61IRP9Pgi, retrieved 29 August 2011

- ^ "Coldplay, Radiohead to be reissued on vinyl", NME, 10 July 2008, archived from the original on 2 November 2011, http://www.webcitation.org/62tCi1PLC, retrieved 2 November 2011

- ^ a b V, Petey (9 January 2009), "Animal Collective Rides Vinyl Wave into '09, Massive 2008 Vinyl Sales Figures Confuse Everyone but B-52s Fans", Tiny Mix Tapes, archived from the original on 1 November 2011, http://www.webcitation.org/62ssMlAPK, retrieved 1 November 2011

- ^ Kreps, Daniel (8 January 2009), "Radiohead, Neutral Milk Hotel Help Vinyl Sales Almost Double In 2008", Rolling Stone, archived from the original on 1 November 2011, http://www.webcitation.org/62stMS5DA, retrieved 1 November 2011

- ^ Kot, Greg (4 October 2008), "Vinyl revival: How a dead format came back for another spin", Chicago Tribune, archived from the original on 6 November 2011, http://www.webcitation.org/630f8hDm4, retrieved 6 November 2011

- ^ "The 7in. revival - fans get back in the groove", The Independent, 18 July 2008, archived from the original on 1 November 2010, http://web.archive.org/web/20101101063232/http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/music/features/the-7in-revival--fans-get-back-in-the-groove-870493.html, retrieved 1 November 2010

- ^ a b Fitzmaurice, Larry (15 January 2009), "Radiohead's First Three Albums Reissued with Extras", Spin, archived from the original on 29 August 2011, http://www.webcitation.org/61JMFAB6A, retrieved 29 August 2011

- ^ a b McCarthy, Sean (18 December 2009), "The Best Re-Issues of 2009: 18: Radiohead: Pablo Honey / The Bends / OK Computer / Kid A / Amnesiac / Hail to the Thief", PopMatters, archived from the original on 29 August 2011, http://www.webcitation.org/61ITIhIyI, retrieved 29 August 2011

- ^ Rossi, Italo (19 March 2009). "Breakfast with Ed O'Brien". Radioheadperu.org. Archived from the original on 29 August 2011. http://www.webcitation.org/61JFUR003. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ^ Kreps, Daniel (15 January 2009), "Radiohead's First Three Albums Reissued with Extras", Rolling Stone, archived from the original on 29 August 2011, http://www.webcitation.org/61JPY4rGt, retrieved 29 August 2011

- ^ Plagenhoef, Scott (16 April 2009), "Radiohead: Pablo Honey: Collector's Edition / The Bends: Collector's Edition / OK Computer: Collector's Edition", Pitchfork Media, archived from the original on 29 August 2011, http://www.webcitation.org/61JGUc0Co, retrieved 29 August 2011

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas, "OK Computer [Collector's Edition [2CD/1DVD]"], Allmusic, archived from the original on 29 August 2011, http://www.webcitation.org/61JQ5iWDw, retrieved 29 August 2011

- ^ Hermes, Will (30 April 2009), "OK Computer (Collector's Edition)", Rolling Stone, archived from the original on 29 August 2011, http://www.webcitation.org/61JMc0JKj, retrieved 29 August 2011

- ^ Modell, Josh (3 April 2009), "Pablo Honey / The Bends / OK Computer", The A.V. Club, archived from the original on 3 October 2011, http://www.webcitation.org/62AQoKIVi, retrieved 3 October 2011

- ^ "Radiohead - OK Computer". Australian-charts.com. Archived from the original on 6 August 2011. http://www.webcitation.org/60k8rt1Ci. Retrieved 6 August 2011.

- ^ "Radiohead - OK Computer". Austriancharts.at. Archived from the original on 6 August 2011. http://www.webcitation.org/60k9Uv02p. Retrieved 6 August 2011.

- ^ a b "Radiohead - OK Computer". Ultratop.be. Archived from the original on 6 August 2011. http://www.webcitation.org/60k9rFMPI. Retrieved 6 August 2011.

- ^ "OK Computer > Charts & Awards > Billboard Albums". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 5 August 2011. http://www.webcitation.org/60jHbL8a3. Retrieved 30 September 2008.

- ^ "Radiohead - OK Computer". Dutchcharts.nl. Archived from the original on 6 August 2011. http://www.webcitation.org/60k9FujVv. Retrieved 6 August 2011.

- ^ "Radiohead - OK Computer". Lescharts.com. Archived from the original on 5 August 2011. http://www.webcitation.org/60jHP0ZUS. Retrieved 5 August 2011.

- ^ "Chartverfolgung / Radiohead / Longplay". musicline.de. Archived from the original on 6 August 2011. http://www.webcitation.org/60k993zaK. Retrieved 6 August 2011.

- ^ "Radiohead - OK Computer". Charts.org.nz. Archived from the original on 6 August 2011. http://www.webcitation.org/60k8odJWN. Retrieved 6 August 2011.

- ^ "Radiohead - OK Computer". Spanishcharts.com. Archived from the original on 6 August 2011. http://www.webcitation.org/60k9g3dIG. Retrieved 6 August 2011.

- ^ "Radiohead - OK Computer". Swedishcharts.com. Archived from the original on 6 August 2011. http://www.webcitation.org/60k90BTpW. Retrieved 6 August 2011.

- ^ "Radiohead - OK Computer". Hitparade.ch. Archived from the original on 6 August 2011. http://www.webcitation.org/60k9dGMaJ. Retrieved 6 August 2011.

- ^ "Artist Chart History - Radiohead". Billboard. Archived from the original on 30 March 2009. http://web.archive.org/web/20090330231836/http://www.billboard.com/bbcom/retrieve_chart_history.do?model.chartFormatGroupName=Albums&model.vnuArtistId=33472&model.vnuAlbumId=1089621. Retrieved 30 September 2008.

- ^ "Search: Radiohead". Charts.org.nz. Archived from the original on 5 August 2011. http://www.webcitation.org/60jG32B39. Retrieved 30 September 2008.

- ^ "Search: Radiohead". Australian-charts.com. Archived from the original on 5 August 2011. http://www.webcitation.org/60jFubn1y. Retrieved 5 August 2011.

- ^ "Search: Radiohead". Swedishcharts.com. Archived from the original on 5 August 2011. http://www.webcitation.org/60jFk69fy. Retrieved 5 August 2011.

- ^ "Eenvoudige zoekopdracht: Radiohead". Dutchcharts.nl. Archived from the original on 5 August 2011. http://www.webcitation.org/60jFclzg8. Retrieved 5 August 2011.

- Bibliography

- Clarke, Martin (2010). Radiohead: Hysterical and Useless. London: Plexus. ISBN 0-85965-439-7.

- Footman, Tim (2007). Welcome to the Machine: OK Computer and the Death of the Classic Album. New Malden: Chrome Dreams. ISBN 1-84240-388-5.

- Griffiths, Dai (2004). Radiohead's OK Computer. 33⅓ series. New York: Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 0-8264-1663-2.

- Harris, John (2004). Britpop!: Cool Britannia and the Spectacular Demise of English Rock. Cambridge: Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-81367-X.

- Moon, Tom (2008). 1,000 Recordings to Hear Before You Die. New York: Workman. ISBN 0-85965-439-7. Archived from the original on 5 August 2011. http://www.webcitation.org/60jDH5t2v. Retrieved 5 August 2011.

- Randall, Mac (2000). Exit Music: The Radiohead Story. New York: Delta Trade Paperbacks. ISBN 0-385-33393-5.

Categories:- 1997 albums

- Albums certified multi-platinum by the Recording Industry Association of America

- Albums certified platinum by the Australian Recording Industry Association

- Albums certified triple platinum by the British Phonographic Industry

- Albums produced by Nigel Godrich

- Albums recorded at Abbey Road Studios

- Capitol Records albums

- English-language albums

- Parlophone albums

- Radiohead albums

- 21 May 1997 (Japan)

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.