- Continental Navy

-

American Revolutionary War Armed Forces United States Continental Army → Commander-in-Chief → Regional departments → Units (1775, 1776, 1777–1784) Continental Navy Continental Marines State forces → List of militia units → List of state navies → Maritime units Great Britain List of British units France List of French units Related topics List of battles Military leadership The Continental Navy was the navy of the United States during the American Revolutionary War, and was formed in 1775. Through the efforts of the Continental Navy's patron, John Adams and vigorous Congressional support in the face of stiff opposition, the fleet cumulatively became relatively substantial when considering the limitations imposed upon the Patriot supply pool.

The main goal of the navy was to intercept shipments of British matériel and generally disrupt British maritime commercial operations. Because of the lack of funding, manpower and resources, the initial fleet consisted of converted merchantmen, with exclusively-designed warships being built later in the conflict. Of the vessels that successfully made it to sea, their success was rare and the effort contributed little to the overall outcome of the rebellion.

The fleet did serve to highlight a few examples of Continental resolve, notably launching Captain John Paul Jones into the limelight. It provided needed experience for a generation of officers who would later go on to command future conflicts which involved the early American navy.

With the war over and the Federal government in need of all available capital, the final vessel of the Continental Navy was auctioned off in 1785 to a private bidder.

Contents

Congressional oversight of construction

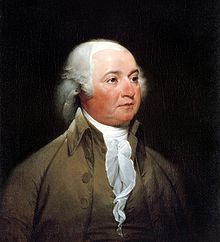

John Adams took an active role in the formation of the navy and the drafting of suitable operational regulations. Painting by John Trumbull, c. 1792-93.

John Adams took an active role in the formation of the navy and the drafting of suitable operational regulations. Painting by John Trumbull, c. 1792-93.

The original intent was to intercept the supply of arms and provisions to British soldiers, who had placed Boston under martial law. George Washington had already informed Congress that he had assumed command of several ships for this purpose, and individual governments of various colonies had outfitted their own warships. The first formal movement for a navy came from Rhode Island, whose State Assembly passed on August 26, 1775, a resolution instructing its delegates to Congress to introduce legislation calling "for building at the Continental expense a fleet of sufficient force, for the protection of these colonies, and for employing them in such a manner and places as will most effectively annoy our enemies..." The measure in the Continental Congress was met with much derision, especially on the part of Maryland delegate Samuel Chase who exclaimed it to be "the maddest idea in the world." John Adams later recalled, "The opposition...was very loud and vehement. It was...represented as the most wild, visionary, mad project that had ever been imagined. It was an infant taking a mad bull by his horns."

During this time, however, the issue arose of Quebec-bound British supply ships carrying desperately needed provisions that could otherwise benefit the Continental Army. The Continental Congress appointed John Adams, Silas Deane, and John Langdon to draft a plan to seize ships from the convoy in question.

Creation

On October 13, 1775, Congress authorized the "fitting out" of the first two armed vessels of the Continental Navy: the official birth of the US Navy. By the end of October, Congress authorized the purchase of four vessels to be outfitted as men-of-war. Soon a Marine Committee of thirteen members was formed which quickly purchased merchantmen and oversaw their proper outfitting and readying for combat. Regulations were drafted by John Adams, a simplification of the naval regulations of the Royal Navy, and adopted November 28, 1775. When it came to selecting commanders for ships, Congress tended to be split evenly between merit and patronage. Among those who were selected for political reasons were Esek Hopkins, Dudley Saltonstall, and Esek Hopkins' son, John Burroughs Hopkins. However, Abraham Whipple, Nicholas Biddle, and John Paul Jones managed to be appointed with backgrounds in marine warfare.

On December 3, the USS Alfred (24 gun), Andrew Doria (14 gun), Cabot (14 gun), and Columbus (24 gun) were commissioned. On December 22, 1775, Esek Hopkins was appointed the naval commander-in-chief, and officers of the navy were commissioned. Saltonstall, Biddle, Hopkins, and Whipple, were commissioned as captains of the Alfred, Andrew Doria, Cabot, and Columbus, respectively.

With this small fleet, complemented by the Providence (12), and Wasp (8), and Hornet (10), Hopkins led the first major naval action of the Continental Navy, in early March 1776, against Nassau, Bahamas, where stores of much-needed gunpowder were seized for the use of the Continental Army. However, success was diluted with the appearance of disease spreading from ship to ship. On April 6, 1776, the squadron, with the addition of the Fly (8) unsuccessfully encountered the 20-gun HMS Glasgow in the first major sea battle of the Continental Navy. Hopkins failed to give any substantive orders other than the order to recall the fleet from the engagement, a move which Captain Nicholas Biddle described as, "away we all went helter, skelter, one flying here, another there."

The Thirteen Frigates

By December 13, 1775, Congress had authorized the construction of 13 new frigates, rather than refitting merchantmen to increase the fleet. Five ships (Hancock, Raleigh, Randolph, Warren, and Washington) were to be rated 32 guns, five (Effingham, Montgomery, Providence, Trumble, and Virginia) 28 guns, and three (Boston, Congress, and Delaware) 24 guns. Of the eight frigates that made it to sea, all were captured or sunk.

Washington, Effingham, Congress, and Montgomery were scuttled or burned in October and November 1777 before going to sea to prevent their capture by the British. USS Virginia, commanded by Captain James Nicholson, made a number of unsuccessful attempts to break through the blockade of Chesapeake Bay. On March 31, 1778, in another attempt, she ran aground near Hampton Roads, where her captain went ashore. Shortly after, commerce raiding, which, as was the practice of the time, brought personal gain to officers and crew.

Most of the eight frigates that went to sea took multiple prizes and had semi-successful cruises before their captures, however there were exceptions. On September 27, 1777, Delaware participated in a delaying action on the Delaware River against the British army pursuing George Washington's forces. The ebb tide arrived and left the Delaware stranded, leading to her capture.

Warren was blockaded in Providence, Rhode Island, shortly after her completion, and did not break out of the blockade until March 8, 1778. After a successful cruise under Captain John Burroughs Hopkins, she was assigned to the ill-fated Penobscot Expedition under Captain Dudley Saltonstall, where she was trapped by the British and burned on August 15, 1779 to prevent her capture.

Hancock, captained by John Manley, managed to capture two merchantmen as well as the Royal Navy vessel HMS Fox. Later on July 8, 1777, however, the Hancock was captured by HMS Rainbow of a pursuing squadron, and became the British man of war Iris.

Randolph took five prizes in her early cruises. On March 7, 1778, she was escorting a convoy of merchantmen when the British 64-gun ship HMS Yarmouth bore down on the convoy. Randolph, under the command of Captain Nicholas Biddle came to the defense of the merchantmen and engaged the heavily superior foe. In the ensuing engagement, the two ships were both severely manhandled but in the course of the action, the magazine of the Randolph exploded causing the destruction of the entire vessel and all but four of her crew. The falling debris from the explosion severely damaged the Yarmouth enough that she could no longer pursue the American ships.

Raleigh, under the command of Captain John Barry, captured three prizes before being run aground in action on September 27, 1778. Her crew scuttled her, but she was raised by the British who refloated her for further use in the name of the Crown.

Boston, under the command of Captains Hector McNeill and Samuel Tucker, had captured 17 prizes in earlier cruises, and had carried John Adams to France in February and March 1778. She was captured (along with the frigate Abraham Whipple) in the fall of Charleston, South Carolina on May 12, 1780.

The final frigate to meet her end of Continental service was the Trumbull. Trumbull, which had not gone to sea until September 1779 under James Nicholson, had gained acclaim in bloody action against the Letter of Marque Watt. On August 28, 1781, she met HMS Iris and General Monk and engaged. In the action, Trumbull was forced to surrender to the former American naval vessels (the General Monk was the captured Rhode Island privateer General Washington, itself recaptured in April 1782 and placed in service with the Continental Navy).

John Paul Jones, the Continental Navy's first seaman to be appointed the rank of 1st Lieutenant. Oil painting by George Bagby Matthews, c. 1890.

John Paul Jones, the Continental Navy's first seaman to be appointed the rank of 1st Lieutenant. Oil painting by George Bagby Matthews, c. 1890.

Before the Franco-American Alliance, the royalist French government attempted to maintain a state of respectful neutrality during the Revolutionary War. That being said, the nation maintained neutrality at face value, often openly harboring Continental vessels and supplying to their needs.

With the presence of American diplomats Benjamin Franklin and Silas Deane, the Continental Navy gained a permanent link to French affairs. Through Franklin and likeminded agents, Continental officers were afforded the ability to receive commissions, survey, and purchase prospective ships for military use.

Early in the conflict, Captains Lambert Wickes and Gustavus Conyngham operated out of various French ports for the purpose of commerce raiding. The French did attempt to enforce her neutrality by seizing USS Dolphin and

The Franco-American squadron closely engages the pair of British frigates on September 23, 1779.

- Dictionary of American Fighting Ships. Naval Historical Center

- William M. Fowler, Rebels Under Sail (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1976)

- Nathan Miller, The US Navy: An Illustrated History (New York: American Heritage, 1977)

- Naval Documents of the American Revolution (Government Printing Office, 1964-). 10 volumes of primary sources.

- Bibliography of Naval Matters in the American Revolution compiled by the United States Army Center of Military History

On September 23, 1779, Jones' squadron was off Flamborough Head when the British men-of-war ship of the line built for service in the Continental Navy, the 74-gun America, was instead offered as a gift to France on September 3, 1782 in compensation for the loss of Le Magnifique in service to the American Revolution.

With the close of the war, Congress was desperate for funds to run the fledgling nation. In response to the financial crisis, Congress considered ending the Continental Navy's existence. One of the justifying factors was the insistence that an extended US Navy would only serve to involve America in foreign conflicts. Furthermore, the cost of maintaining a standing navy placed an additional drain on the limited revenues Congress was able to raise.

On August 1, 1785 the financially strapped Congress auctioned off the last remaining Continental Navy vessel, Alliance, for $26,000.

Of the approximately 65 vessels (new, converted, chartered, loaned, and captured) that served at one time or another with the Continental Navy, only 11 survived the war without having been destroyed, sunk, or captured. The Continental Navy posed no significant threat to Royal Navy supremacy and did little to alter the course of the war. The Continental Navy did, however, keep up American morale and spirit as the war dragged on, adding to the hope that one day the 13 Colonies would emerge successful from their struggle.[citation needed]

See also

References

External links

|

||||||||||||