- Eye movement (sensory)

-

For other uses, see Eye movement (disambiguation).

Eye movement is the voluntary or involuntary movement of the eyes, helping in acquiring, fixating and tracking visual stimuli. It may also compensate for a body movement, such as when moving the head. In addition, rapid eye movement occurs during REM sleep.

Contents

Introduction

Eyes are the visual organs that have the retina, a specialized type of brain tissue containing photoreceptors. These specialised cells convert light into electrochemical signals through the ganglion cell layer and travel along the optic nerve fibers to the brain.

Primates and many other invertebrates use two types of voluntary eye movement to track objects of interest: smooth pursuit and saccades.[1] These movements appear to be initiated by a small cortical region in the brain's frontal lobe.[2][3] This is corroborated by removal of the frontal lobe. In this case, the reflexes (such as reflex shifting the eyes to a moving light) are intact, though the voluntary control is obliterated.[4]

Varieties and purpose of movement

There are three main basic types of eye movements:

- Irregular movements at 30-70 per second, or irregular excursions of 20 seconds of arc

- Saccades, which are worth a few minutes of arc, moving at regular intervals about one second

- Slow irregular drifts up to 6 minutes of arc

These movements are needed to provide a new set of rods and cones, because, if it was fixed on one set, the signal would be cancelled due to adaptation of the stimulus after some time. Saccades are faster than convergence and smooth pursuit.[4]

Physiology

Types

Eye movements are typically classified as either ductions, versions, or vergences.[5][6] A duction is an eye movement involving only one eye; a version is an eye movement involving both eyes in which each eye moves in the same direction; a vergence is an eye movement involving both eyes in which each eye moves in opposite directions.

- Fixational eye movement

- Gaze-stabilizing mechanisms

- Gaze shifting mechanisms

- Saccadic movement

- Smooth pursuit

- Vergence movement

Yoked movement vs. antagonistic movement

The visual system in the brain is too slow to process that information if the images are slipping across the retina at more than a few degrees per second.[7] Thus, to be able to see while we are moving, the brain must compensate for the motion of the head by turning the eyes. Another specialisation of visual system in many vertebrate animals is the development of a small area of the retina with a very high visual acuity. This area is called the fovea, and covers about 2 degrees of visual angle in people. To get a clear view of the world, the brain must turn the eyes so that the image of the object of regard falls on the fovea. Eye movements are thus very important for visual perception, and any failure to make them correctly can lead to serious visual disabilities. To see a quick demonstration of this fact, try the following experiment: hold your hand up, about one foot (30 cm) in front of your nose. Keep your head still, and shake your hand from side to side, slowly at first, and then faster and faster. At first you will be able to see your fingers quite clearly. But as the frequency of shaking passes about 1 Hz, the fingers will become a blur. Now, keep your hand still, and shake your head (up and down or left and right). No matter how fast you shake your head, the image of your fingers remains clear. This demonstrates that the brain can move the eyes opposite to head motion much better than it can follow, or pursue, a hand movement. When your pursuit system fails to keep up with the moving hand, images slip on the retina and you see a blurred hand.

The brain must point both eyes accurately enough that the object of regard falls on corresponding points of the two retinas to avoid the perception of double vision. In primates (monkeys, apes, and humans), the movements of different body parts are controlled by striated muscles acting around joints. The movements of the eye are slightly different in that the eyes are not rigidly attached to anything, but are held in the orbit by six extraocular muscles.

Anatomy

Extraocular muscles

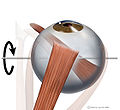

Each eye has six extraocular muscles (EOM) that bring about the various eye movements:

- Lateral rectus, (supplied by Abducens nerve)

- Medial rectus, (supplied by Oculomotor nerve)

- Inferior rectus, (supplied by Oculomotor nerve)

- Superior rectus, (supplied by Oculomotor nerve)

- Inferior oblique, (supplied by Oculomotor nerve) and

- Superior oblique (supplied by Trochlear nerve)

-

Eye movement of lateral rectus muscle, superior view

-

Eye movement of medial rectus muscle, superior view

-

Eye movement of inferior rectus muscle, superior view

-

Eye movement of superior rectus muscle, superior view

-

Eye movement of superior oblique muscle, superior view

-

Eye movement of inferior oblique muscle, superior view

credit: Patrick J. LynchWhen the muscles exert differential tensions (contractions in synergistic muscles and relaxation of antagonist muscles), a torque is exerted on the globe that causes it to turn. This is an almost pure rotation, with only about one millimeter of translation.[8] Thus, the eye can be considered as undergoing rotations about a single point in the center of the eye.

Neuroanatomy

The brain exerts ultimate control over both voluntary and involuntary eye movements. Three cranial nerves carry signals from the brain to control the extraocular muscles. They are:

- III cranial nerve: Oculomotor nerve/Oculomotor nucleus

- IV cranial nerve: Trochlear nerve/Trochlear nucleus

- VI cranial nerve: Abducens nerve/Abducens nucleus

- Brain

- Cerebral cortex

- Frontal lobe – frontal eye fields (FEF), medial eye fields (MEF), supplementary eye fields (SEF), dorsomedial frontal cortex (DMFC)

- Parietal lobe – lateral intraparietal area (LIP), middle temporal area (MT), medial superior temporal area (MST)

- Occipital lobe

- Cerebellum[9]

- Cerebral cortex

- Midbrain

- Pretectum – Pretectal nuclei

- Superior colliculus

- Brain stem

- Superior colliculus (SC)

- Premotor nuclei in the reticular formation (PMN)

- Paramedian pontine reticular formation

- Cranial nerves

- III: Oculomotor nerve/Oculomotor nucleus

- IV: Trochlear nerve/Trochlear nucleus

- VI: Abducens nerve/Abducens nucleus

- Vestibular nuclei

- Medial longitudinal fasciculus

- Nucleus prepositus hypoglossi

Disorders

Symptoms

- Patients with eye movement disorders may report diplopia, nystagmus, poor visual acuity or cosmetic blemish from squint of the eyes.

Etiology

- Innervational

- Supranuclear

- Nuclear

- Nerve

- Synapse

- Muscle anomalies

- Maldevelopment (e.g. Hypertrophy, atrophy/dystrophy)

- Malinsertion

- Scarring secondary to alignment surgery

- Muscle diseases (e.g. Myasthenia gravis)

- Orbital anomalies

- Tumor (e.g. rhabdomyosarcoma)

- Excess fat behind globe (e.g. thyroid conditions)

- Bone fracture

- Check ligament (e.g. Brown's syndrome, or Superior tendon sheath syndrome)

Selected disorders

- Congenital fourth nerve palsy

- Duane syndrome

- Internuclear ophthalmoplegia

- Nystagmus

- Ophthalmoparesis

- Opsoclonus

- Sixth (abducent) nerve palsy

See also

- Convergence micropsia

- Dissociated vertical deviation

- Eye exercises

- Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing

- Eye movement in language reading

- Eye movement in music reading

- Eye tracking

- Gaze-contingency paradigm

- Microsaccade

- Ocular tremor

- Orthoptist

- Rapid eye movement sleep

- Strabismus

- Voluntary Nystagmus

References

- ^ Krauzlis, RJ. The control of voluntary eye movements: new perspectives. The Neuroscientist. 2005 Apr;11(2):124-37. PMID 15746381.

- ^ Heinen SJ, Liu M. "Single-neuron activity in the dorsomedial frontal cortex during smooth-pursuit eye movements to predictable target motion." Vis Neurosci. 1997 Sep-Oct;14(5):853-65. PMID 9364724

- ^ Tehovnik EJ, Sommer MA, Chou IH, Slocum WM, Schiller PH. "Eye fields in the frontal lobes of primates." Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2000 Apr;32(2-3):413-48. PMID 10760550

- ^ a b "Sensory Reception: Human Vision: Structure and function of the Human Eye" Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1987

- ^ Kanski, JJ. Clinical Ophthalmology: A Systematic Approach. Boston:Butterworth-Heinemann;1989.

- ^ Awwad, S. "Motility & Binocular Vision". EyeWeb.org.

- ^ Westheimer, Gerald & McKee, Suzanne P.; "Visual acuity in the presence of retinal-image motion". Journal of the Optical Society of America 1975 65(7), 847-50.

- ^ Carpenter, Roger H.S.; Movements of the Eyes (2nd ed.). Pion Ltd, London, 1988. ISBN 0-85086-109-8.

- ^ Robinson FR, Fuchs AF. "The role of the cerebellum in voluntary eye movements." Annu Rev Neurosci. 2001;24:981-1004. PMID 11520925

External links

- eMedicine – Extraocular Muscles, Actions

- Oculomotor Control – Nystagmus and Dizziness Department of Otolaryngology – Queen's University at Kingston, Canada

- Fixation Movements of the Eyes

- An eye movement simulator, which shows changes in eye movements for any given muscle or nerve impairment.

Sensory system: Visual system and eye movement pathways Visual perception 1° (Bipolar cell of Retina) → 2° (Ganglionic cell) → 3° (Optic nerve → Optic chiasm → Optic tract → LGN of Thalamus) → 4° (Optic radiation → Cuneus and Lingual gyrus of Visual cortex → Blobs → Globs)Muscles of orbit TrackingHorizontal gazeVertical gazePupillary reflex Pupillary dilation1° (Posterior hypothalamus → Ciliospinal center) → 2° (Superior cervical ganglion) → 3° (Sympathetic root of ciliary ganglion → Nasociliary nerve → Long ciliary nerves → Iris dilator muscle)1° (Retina → Optic nerve → Optic chiasm → Optic tract → Visual cortex → Brodmann area 19 → Pretectal area) → 2° (Edinger-Westphal nucleus) → 3° (Short ciliary nerves → Ciliary ganglion → Ciliary muscle)Circadian rhythm M: EYE

anat(g/a/p)/phys/devp/prot

noco/cong/tumr, epon

proc, drug(S1A/1E/1F/1L)

Categories:

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.