- Sex differences in humans

-

Male and female anatomy. Note that these models have had body hair and male facial hair removed and head hair trimmed.

Male and female anatomy. Note that these models have had body hair and male facial hair removed and head hair trimmed.

A sex difference is a distinction of biological and/or physiological characteristics associated with either males or females of a species. These can be of several types, including direct and indirect. Direct being the direct result of differences prescribed by the Y-chromosome, and indirect being a characteristic influenced indirectly (e.g. hormonally) by the Y-chromosome. Sexual dimorphism is a term for the phenotypic difference between males and females of the same species.

Direct sex differences follow a binary distribution. Through the process of meiosis and fertilization (with rare exceptions), each individual is created with zero or one Y-chromosome. The complimentary result for the X-chromosome follows, either a double or a single X. Therefore, direct sex differences are usually binary in expression (although the deviations in complex biological processes produce a menagerie of exceptions). These include, most conspicuously, male (vs female) gonads.

Indirect sex differences are general differences in class, as quantified by empirical data and statistical analysis. Most differing characteristics will conform to a bell-curve (i.e. normal) distribution which can be broadly described by the mean (peak distribution) and standard deviation (indicator of size of range). Often only the mean or mean difference between sexes is given. This may or may not preclude overlap in distributions. For example, males are taller than females on average,[1] but an individual female may be taller than an individual male.

The most obvious differences between males and females include all the features related to reproductive role, notably the endocrine (hormonal) systems and their physiological and behavioural effects, including gonadal differentiation, internal and external genital and breast differentiation, and differentiation of muscle mass, height, and hair distribution.

Sex determination and differentiation

The Human Y Chromosome showing the SRY gene. SRY is a gene which regulates sexual differentiation.

The Human Y Chromosome showing the SRY gene. SRY is a gene which regulates sexual differentiation.

The human genome consists of two copies of each of 23 chromosomes (a total of 46). One set of 23 comes from the mother and one set comes from the father. Of these 23 pairs of chromosomes, 22 are autosomes, and one is a sex chromosome. There are two kinds of sex chromosomes–"X" and "Y". In humans and in almost all other mammals, females carry two X chromosomes, designated XX, and males carry one X and one Y, designated XY.

A human egg contains only one set of chromosomes (23) and is said to be haploid. Sperm also have only one set of 23 chromosomes and are therefore haploid. When an egg and sperm fuse at fertilization, the two sets of chromosomes come together to form a unique "diploid" individual with 46 chromosomes.

The sex chromosome in a human egg is always an X chromosome, since a female only has X sex chromosomes. In sperm, about half the sperm have an X chromosome and half have a Y chromosome. If an egg fuses with a sperm with a Y chromosome, the resulting individual is usually male. If an egg fuses with a sperm with an X chromosome, the resulting individual is usually female. An egg's sex chromosome is always an X, so it is the sperm's sex chromosome that determines an individual's sex. There are rare exceptions to this rule in which, for example, XX individuals develop as males or XY individuals develop as females.

Sexual dimorphism

- For information about how males and females develop differences throughout the lifespan, see sexual differentiation.

Sexual dimorphism (two forms) refers to the general phenomenon in which male and female forms of an organism display distinct morphological characteristics or features.

Sexual dimorphism in humans is the subject of much controversy, especially relating to mental ability and psychological gender. (For a discussion, see biology of gender, sex and intelligence, gender, and transgender.) Obvious differences between men and women include all the features related to reproductive role, notably the endocrine (hormonal) systems and their physical, psychological and behavioral effects. Although sex is a binary dichotomy, with "male" and "female" representing opposite and complementary sex categories for the purpose of reproduction, a small number of individuals have an anatomy that does not conform to either male or female standards, or contains features closely associated with both. Such individuals, described as intersexuals, are sometimes infertile but are often capable of reproducing.

Some biologists[who?] theorise that a species' degree of sexual dimorphism is inversely related to the degree of paternal investment in parenting. Species with the highest sexual dimorphism, such as the pheasant, tend to be those species in which the care and raising of offspring is done only by the mother, with no involvement of the father (low degree of paternal investment). This would also explain the moderate degree of sexual dimorphism in humans, who have a moderate degree of paternal investment compared to most other mammals.

Size, weight and body shape

See also: Secondary sex characteristics, Human body shape, and Female body shape- Externally, the most sexually dimorphic portions of the human body are the chest, the lower half of the face, and the area between the waist and the knees.[2]

- Males weigh about 15 % more than females, on average. For those older than 20 years of age, males in the US have an average weight of 86.1 kg (190 lbs), whereas females have an average weight of 74 kg (163 lbs).[3]

- On average, men are taller than women, by about 15 cm (6 inches).[1] American males who are 20 years old or older have an average height of 175.8 cm (5 ft 9 in). The average height of corresponding females is 162 cm (5 ft 4in).[3]

- On average, men have a larger waist in comparison to their hips (see waist-hip ratio) than women.

- Women have a larger hip section than men, an adaptation for giving birth to infants with large skulls.

Skeleton and muscular system

Strength, power and muscle mass

On average, males are physically stronger than females. The difference is due to females, on average, having less total muscle mass than males, and also having lower muscle mass in comparison to total body mass. While individual muscle fibers have similar strength, males have more fibers due to their greater total muscle mass. The greater muscle mass of males is in turn due to a greater capacity for muscular hypertrophy as a result of men's higher levels of testosterone. Males remain stronger than females, when adjusting for differences in total body mass. This is due to the higher male muscle-mass to body-mass ratio.[4]

As a result, gross measures of body strength suggest an average 40-50% difference in upper body strength between the sexes as a result of this difference, and a 20-30% difference in lower body strength.[5] This is supported by another study that found females are about 52-66 percent as strong as males in the upper body (34-48% difference), and about 70-80 percent as strong in the lower body (20-30% difference).[6] One study of muscle strength in the elbows and knees—in 45 and older males and females—found the strength of females to range from 42 to 63% of male strength.[7]

Comparison between a male (left) and a female pelvis (right).

Skeleton

- Males, on average, have denser, stronger bones, tendons, and ligaments.

- In men, the second digit (index finger) tends to be shorter than the fourth digit (ring finger), while in women the second digit tends to be longer than the fourth (see digit ratio).[8]

- Men have a more pronounced 'Adam's Apple' or thyroid cartilage (and deeper voices) due to larger vocal cords.[9]

- On average, men have longer canine teeth than women.

- Male skulls and head bones have a different shape than female skulls. One difference is in the roundness of the eye cavities, another is the male's bony brow, and a third difference is the shape of the jaw.

- Male and female pelvises are shaped differently. The female pelvis features a wider pelvic cavity, which is necessary when giving birth. The female pelvis has evolved to its maximum width for childbirth — an even wider pelvis would make women unable to walk. In contrast, human male pelves did not evolve to give birth and are therefore slightly more optimized for walking.[10] The female pelvis is larger and broader than the male pelvis which is taller, narrower, and more compact. The female inlet is larger and oval in shape, while the male inlet is more heart-shaped.[11]

- Contrary to popular belief, however, males and females do not differ in the number of ribs; both have twelve pairs.[12]

Respiratory system

Males typically have larger tracheae and branching bronchi, with about 56 percent greater lung volume per body mass. They also have larger hearts, 10 percent higher red blood cell count, higher haemoglobin, hence greater oxygen-carrying capacity. They also have higher circulating clotting factors (vitamin K, prothrombin and platelets). These differences lead to faster healing of wounds and higher peripheral pain tolerance.[13] []

Skin and hair

See also: Androgenic hair and Human skin According to most studies,[citation needed] Red hair is much more common and blond hair is more common in females than in males. On average females also have a lighter colored skin and are more likely to have green eyes.

According to most studies,[citation needed] Red hair is much more common and blond hair is more common in females than in males. On average females also have a lighter colored skin and are more likely to have green eyes.

Skin

Male skin is thicker (more collagen) and oilier (more sebum) than female skin.[14]

The skin of females is warmer on average than that of males.

Hair

On average, males have more body hair than females. Males have relatively more of the type of hair called terminal hair, especially on the face, chest, abdomen and back. In contrast, females have more vellus hair. Vellus hairs are smaller and therefore less visible.

Baldness is much more common in males than in females. The main cause for this is male pattern baldness or androgenic alopecia. Male pattern baldness is a condition where hair starts to get lost in a typical pattern of receding hairline and hair thinning on the crown, and is caused by hormones and genetic predisposition.[15]

Color

On average and after the end of puberty, males have darker hair than females and according to most studies they also have darker skin (male skin is also redder, but this is due to greater blood volume rather than melanin).[citation needed] Male eyes are also more likely to be one of the darker eye colors. Conversely, women are lighter-skinned than men in all human populations.[16][non-primary source needed] The differences in color are mainly caused by higher levels of melanin in the skin, hair and eyes in males.[17][18][non-primary source needed] In one study, almost twice as many females as males had red or auburn hair. A higher proportion of females were also found to have blond hair, whereas males were more likely to have black or dark brown hair.[19][non-primary source needed] Another study found green eyes, which are a result of lower melanin levels, to be much more common in women than in men, at least by a factor of two.[16][20][non-primary source needed] However, a more recent study found that while women indeed tend to have a lower frequency of black hair, men on the other hand had a higher frequency of red-blond hair, blue eyes and lighter skin. According to one theory the cause for this is a higher frequency of genetic recombination in women than in men, possibly due to sex-linked genes, and as a result women tend to show less phenotypical variation in any given population.[21][22][non-primary source needed] Also, women tend to bleach or color their hair while men tend not to, which would make the proportion of blond or red-haired women seem higher than what it is naturally.

The human sexual dimorphism in color seems to be greater in populations that are medium in skin color than in very light or very dark colored populations.[16][non-primary source needed]

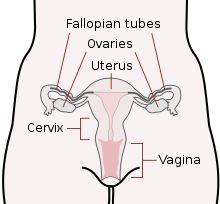

Sexual organs and reproductive systems

See also: Male reproductive system and Female reproductive systemMen and women have different sex organs. Women have two ovaries that stores the eggs, and uterus which is connected to a vagina. Men have testicles that produce sperm. The testicles are placed in the scrotum behind the penis. The male penis and scrotum are external extremities, whereas the female sex organs are placed "inside" the body.

Men's orgasm is nearly essential ("nearly" as small groups of sperm can escape the penis before orgasm is reached) for reproduction, whereas female orgasm is not. The female orgasm was believed to have no obvious function other than to be pleasurable although some evidence suggests that it may have evolved as a discriminatory advantage in regards to mate selection.[23]

Reproductive capacity and cost

Men typically produce billions of sperm each month,[24] many of which are capable of fertilization. Women typically produce one egg a month that can be fertilized into an embryo. Thus during a lifetime men are able to father a significantly greater number of children than women can give birth to. The most fertile woman, according to the Guinness Book of World Records, was the wife of Feodor Vassilyev of Russia (1707–1782) who had 67 surviving children. The most prolific father of all time is believed to be the last Sharifian Emperor of Morocco, Mulai Ismail (1646–1727) who reportedly fathered more than 800 children from a harem of 500 women.

Fertility

Female fertility declines after age 30 and ends with the menopause.[25][26] Pregnancy in the 40s or later has been correlated with increased chance of Down's Syndrome in the children.[27] Men are capable of fathering children into old age. Paternal age effects in the children include multiple sclerosis,[28] autism,[29] breast cancer [30] and schizophrenia,[31] as well as reduced intelligence.[32] Adriana Iliescu was reported as the world's oldest woman to give birth, at age 66. Her record stood until Maria del Carmen Bousada de Lara gave birth to twin sons at Sant Pau Hospital in Barcelona, Spain on December 29, 2006, at the age of 67. In both cases IVF was used. The oldest known father was former Australian miner Les Colley, who fathered a child at age 93.[33]

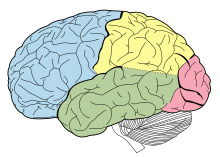

Brain and nervous system

Main article: Sex and psychologyBrain

The brains of many animals, including humans, are significantly different for males and females of the species.[34]

Brain size

Human males, on average, have larger brains than females.

In 1861, Paul Broca examined 432 human brains and found that the brains of males had an average weight of 1325 grams, while the brains of females had an average weight of 1144 grams. More recently, a 1992 study of 6,325 Army personnel found that men's brains had an average volume of 1442 cm³, while the women averaged 1332 cm³. These differences were shown to be smaller but to persist even when adjusted for body size measured as body height or body surface, such that women averaged 100 g less brain mass than men of equal size.[35]

According to another estimate, on average, male brains have approximately 4 % more cells and weigh 100 grams more than female brains do. However, both sexes have a similar brain weight to body weight ratio. Female brains are more compact than male brains in that, though smaller, they are more densely packed with neurons, particularly in the region responsible for language.[36]

In studies concerning intelligence, it has been suggested that the ratio of brain weight to body weight (rather than actual brain weight) is more predictive of IQ levels. While men's brains are an average of 10-15% larger and heavier than women's brains, some researchers propose that the ratio of brain to body size does not differ between the sexes.[37][38] However, some argue that since brain-to-body-size ratios tend to decrease as body size increases, a sex difference in brain-weight ratios still exists between men and women of the same size.[35]

Brain structure

The male and female brains show some differences in internal structure. One difference is the proportions of white matter relative to grey matter.

There are also differences in the structure of and in specific areas of the brain. For instance, two studies found that men have larger parietal lobes, though another study failed to find any statistically significant difference.[39][40] At the same time, females have larger Wernicke's and Broca's areas, areas responsible for language processing.[41] Studies using MRI scanning have shown that the auditory and language-related regions in the left hemisphere are proportionally expanded in females versus in males. Conversely, the primary visual, and visuo-spatial association areas of the parietal lobes are proportionally larger in males.[42] Evidence of a sex difference in the relative size of the corpus callosum was discussed during the 1980s and 90s.[43] However, a 1997 meta-study concluded that there is no relative size difference, and that the larger corpus callosum in males is due to generally larger brains in males on average.[44]

In total and on average, females have a higher percentage of grey matter in comparison to males, and males a higher percentage of white matter.[45][46] However, some researchers maintain that as males have larger brains on average than females, when adjusted for total brain volume, the grey matter differences between sexes is small or nonexistent. Thus, the percentage of grey matter appears to be more related to brain size than it is to gender.[47][48]

A proposed alternative way of measuring intelligence is by using grey matter or white matter volume in the brain as an indicator. The former is used for information processing, whereas the latter makes up the connections between processing centers. In 2005, Haier et al. reported that, compared with men, women show more white matter and fewer grey matter areas as related to intelligence. However, he concluded that "men and women apparently achieve similar IQ results with different brain regions, suggesting that there is no singular underlying neuroanatomical structure to general intelligence and that different types of brain designs may manifest equivalent intellectual performance." [49] Using brain mapping, it was shown that men have more than six times the amount of gray matter related to general intelligence than women, and women have nearly ten times the amount of white matter related to intelligence than men.[50] They also report that the brain areas correlated with IQ differ between the sexes. In short, men and women apparently achieve similar IQ results with different brain regions.[51]

Other differences that have been established include greater length in males of myelinated axons in their white matter (176,000 km compared to 146,000 km);[45] and 33% more synapses per mm3 of cerebral cortex.[52] Another difference is that females generally have faster blood flow to their brains and lose less brain tissue as they age than males do.[53] Additionally, depression and chronic anxiety are much more common in women than in men, and it has been speculated, by some, that this is due to differences in the brain's serotonin system).[54]

Genetic and hormonal causes

Both genes and hormones affect the formation of human brains before birth, as well as the behavior of adult individuals. Several genes that code for differences between male and female brains have been identified. In the human brain, a difference between sexes was observed in the transcription of the PCDH11X/Y gene pair, a pair unique to Homo sapiens.[55] It has been argued[by whom?] that the Y chromosome is primarily responsible for males being more susceptible to mental illnesses.

Hormones significantly affect human brain formation, as well as brain development at puberty. A 2004 review in Nature Reviews Neuroscience observed that "because it is easier to manipulate hormone levels than the expression of sex chromosome genes, the effects of hormones have been studied much more extensively, and are much better understood, than the direct actions in the brain of sex chromosome genes." It concluded that while "the differentiating effects of gonadal secretions seem to be dominant," the existing body of research "support the idea that sex differences in neural expression of X and Y genes significantly contribute to sex differences in brain functions and disease."[56]

Sensory systems

Main article: Sex Differences in Sensory Systems- Females have a more sensitive sense of smell than males, both in the differentiation of odors, and in the detection of slight or faint odors.[57]

- There is also indication that females are better at discerning differences in colours, while males are more aware of, and capable of discerning movement.[citation needed]

- Females have more pain receptors in the skin. That may contribute to the lower pain tolerance of women.[58]

Tissues and hormones

- Women generally have a higher body fat percentage than men.[1]

- Women usually have lower blood pressure than men, and women's hearts beat faster, even when they are asleep.[59]

- Men generally have more muscle tissue mass, particularly in the upper body.

- Men and women have different levels of certain hormones. Men have a higher concentration of androgens while women have a higher concentration of estrogens. The main male-associated hormone is testosterone.

- Adult men have approximately 5.2 million red blood cells per cubic millimeter of blood, whereas women have approximately 4.6 million.[60]

- Females typically have more white blood cells (stored and circulating), more granulocytes and B and T lymphocytes. Additionally, they produce more antibodies at a faster rate than males. Hence they develop fewer infectious diseases and succumb for shorter periods.[13]

Health

Life span

Females live longer than males in most countries around the world. One possible explanation is the generally more risky behavior engaged in by males. More males than females die young because of war, criminal activity, and accidents. However, the gap between males and females is decreasing in many developed countries as more women take up unhealthy practices that were once considered masculine like smoking and drinking alcohol.[61] In Russia, however, the sex-associated gap has been increasing as male life expectancy declines.[62]

Illness and injury

Sex chromosome disorders

Certain diseases and conditions are clearly sex related in that they are caused by the same chromosomes that regulate sex differentiation. Some conditions are X-linked recessive, in that the gene is carried on the X chromosome. Genetic females (XX) will show symptoms of the disease only if both their X chromosomes are defective with a similar deficiency, whereas genetic males (XY) will show symptoms of the disease if their only X chromosome is defective. (A woman may carry such a disease on one X chromosome but not show symptoms if the other X chromosome works sufficiently.) For this reason, such conditions are far more common in males than in females. Examples of X-linked recessive conditions are color blindness, hemophilia, and Duchenne muscular dystrophy.

No vital genes reside only on the Y chromosome, since roughly half of humans (females) do not have Y chromosomes. Still, there are diseases that are caused by a defective Y chromosome or of a defective number of them. One human disease linked to a defect on the Y chromosome is defective testicular development. Other conditions include Klinefelter's syndrome and XX male syndrome.

Differences not linked to sex chromosomes

The World Health Organization (WHO) has produced a number of reports on gender and health.[63] The following trends are shown:

- Overall rates of mental illness are similar for men and women. There is no significant gender difference in rates of schizophrenia and bipolar depression. Women are more likely to suffer from unipolar depression, anxiety, eating disorders, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Men are more likely to suffer from alcoholism and antisocial personality disorder, as well as developmental psychiatric disorders such as autism spectrum disorders and Tourette syndrome.

- Before menopause, women are less likely to suffer from cardiovascular disease. However, after age 60, the risk for both men and women is the same.

- Overall, men are more likely to suffer from cancer, with much of this driven by lung cancer. In most countries, more men than women smoke, although this gap is narrowing especially among young women.

- Women are twice as likely to be blind as men. In developed countries, this may be linked to higher life expectancy and age-related conditions. In developing countries, women are less likely to get timely treatments for conditions that lead to blindness such as cataracts and trachoma.

- Women are more likely to suffer from osteoarthritis and osteoporosis.

Infectious disease prevalence varies - this is largely due to cultural and exposure factors. In particular the WHO notes that:[63]

- Worldwide, more men than women are infected with HIV. The exception is sub-Saharan Africa, where more women than men are infected.

- Adult males are more likely to be diagnosed with tuberculosis.

Some other sex-related health differences include:

- Anterior cruciate ligament injuries, especially in basketball, occur more often in women than in men.

- From conception to death, but particularly before adulthood, females are generally less vulnerable than males to developmental difficulties and chronic illnesses.[64][65] This could be due to females having two x chromosomes instead of just one,[66] or in the reduced exposure to testosterone.[67]

Sex ratio

Main article: Human sex ratioThe sex ratio for the entire world population is 101 males to 100 females. However, in developed countries, there are more females than males.[68]

See also

- Gender-based medicine

- Genetics of gender

- Gender differences in coping

- Sexual dimorphism

- Sex differentiation

- Sex and intelligence

- Virilization

- List of homologues of the human reproductive system

- Man flu

References

Notes

- ^ a b Gustafsson A & Lindenfors P (2004). "Human size evolution: no allometric relationship between male and female stature". Journal of Human Evolution 47 (4): 253–266. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2004.07.004. PMID 15454336.

- ^ Gray 1918, Nowell 1926, Green 2000, et al.

- ^ a b Ogden et al (2004). Mean Body Weight, Height,and Body Mass Index, United States 1960–2002 Advance Data from Vital and Health Statistics, Number 347, October 27, 2004.[dead link]

- ^ Maughan R J, Watson J S, Weir J (1983). "Strength and cross-sectional area of human skeletal muscle". The Journal of Physiology 338 (1): 37–49. PMC 1197179. PMID 6875963. http://jp.physoc.org/content/338/1/37.abstract.

- ^ Gender Differences in Endurance Performance and Training[dead link]

- ^ Miller, AE; MacDougall, JD; Tarnopolsky, MA; Sale, DG (1993). "Gender differences in strength and muscle fiber characteristics". European journal of applied physiology and occupational physiology 66 (3): 254–62. doi:10.1007/BF00235103. PMID 8477683.

- ^ Frontera, Hughes, Lutz, Evans (1991). "A cross-sectional study of muscle strength and mass in 45- to 78-yr-old men and women". J Appl Physiol 71 (2): 644–50. PMID 1938738. http://jap.physiology.org/cgi/content/abstract/71/2/644.

- ^ Churchchill, AJG; Manning, JT; Peters, M. (2007). "The effects of sex, ethnicity, and sexual orientation on self-measured digit ratio (2D:4D)". Archives of Sexual Behavior 36 (2): 251–260. doi:10.1007/s10508-006-9166-8. PMID 17394056.

- ^ http://wiki.answers.com/Q/Why_do_men_have_Adam's_apples

- ^ Merry (2005), p 48

- ^ Thieme Atlas of Anatomy (2006), p 112

- ^ Number of Ribs

- ^ a b Glucksman, A. (1981) Sexual Dimorphism in Human and Mammalian Biology and Pathology (Academic Press, 1981), pp. 66-75

- ^ Gender-related features of skin Procter & Gamble Haircare Research Centre 1997[dead link]

- ^ Male Pattern Baldness

- ^ a b c Frost, P. (2007). Sex linkage of human skin, hair, and eye color

- ^ Frost, P. (1988). "Human skin color: A possible relationship between its sexual dimorphism and its social perception". Perspectives in Biology and Medicine 32 (1): 38–58. PMID 3059317.

- ^ Frost, P. (2006). "European hair and eye color - A case of frequency-dependent sexual selection?". Evolution and Human Behavior 27 (2): 85–103. doi:10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2005.07.002.

- ^ Duffy DL, Montgomery GW, Chen W, et al. (February 2007). "A Three–Single-Nucleotide Polymorphism Haplotype in Intron 1 of OCA2 Explains Most Human Eye-Color Variation". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 80 (2): 241–52. doi:10.1086/510885. PMC 1785344. PMID 17236130. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1785344.

- ^ Sulem, Patrick; Gudbjartsson, Daniel F; Stacey, Simon N; Helgason, Agnar; Rafnar, Thorunn; Magnusson, Kristinn P; Manolescu, Andrei; Karason, Ari et al. (2007). "Genetic determinants of hair, eye and skin pigmentation in Europeans". Nature Genetics 39 (12): 1443–52. doi:10.1038/ng.2007.13. PMID 17952075.

- ^ Branicki, Wojciech; Brudnik, Urszula; Wojas-Pelc, Anna (2009). "Interactions BetweenHERC2,OCA2andMC1RMay Influence Human Pigmentation Phenotype". Annals of Human Genetics 73 (2): 160–70. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1809.2009.00504.x. PMID 19208107.

- ^ Interaction between loci affecting human pigmentation in Poland

- ^ Psychology Today, The Orgasm Wars

- ^ MedlinePlus Encyclopedia Semen analysis

- ^ Graph @ FertilityLifelines.

- ^ Graph @ Epigee.org.

- ^ Age and Fertility: A Guide for Patients, American Society for Reproductive Medicine, 2003.

- ^ Montgomery SM, Lambe M, Olsson T, Ekbom A (November 2004). "Parental age, family size, and risk of multiple sclerosis". Epidemiology 15 (6): 717–23. doi:10.1097/01.ede.0000142138.46167.69. PMID 15475721. http://meta.wkhealth.com/pt/pt-core/template-journal/lwwgateway/media/landingpage.htm?issn=1044-3983&volume=15&issue=6&spage=717.

- ^ Reichenberg A, Gross R, Weiser M, et al. (September 2006). "Advancing paternal age and autism". Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 63 (9): 1026–32. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.63.9.1026. PMID 16953005. http://archpsyc.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/full/63/9/1026.

- ^ Choi JY, Lee KM, Park SK, et al. (2005). "Association of paternal age at birth and the risk of breast cancer in offspring: a case control study". BMC Cancer 5: 143. doi:10.1186/1471-2407-5-143. PMC 1291359. PMID 16259637. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2407/5/143.

- ^ Sipos A, Rasmussen F, Harrison G, et al. (November 2004). "Paternal age and schizophrenia: a population based cohort study". BMJ 329 (7474): 1070. doi:10.1136/bmj.38243.672396.55. PMC 526116. PMID 15501901. http://bmj.com/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=15501901.

- ^ Saha S, Barnett AG, Foldi C, et al. (March 2009). Brayne, Carol. ed. "Advanced Paternal Age Is Associated with Impaired Neurocognitive Outcomes during Infancy and Childhood". PLoS Med. 6 (3): e40. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000040. PMC 2653549. PMID 19278291. http://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000040.

- ^ oldest birth parents

- ^ Robert W Goy and Bruce S McEwen. Sexual Differentiation of the Brain: Based on a Work Session of the Neurosciences Research Program. MIT Press Classics. Boston: MIT Press, 1980.

- ^ a b Ankney, C.D. (1992). "Sex Differences in Relative Brain Size: The Mismeasure of Woman, Too?". Intelligence 16 (3–4): 329–336. doi:10.1016/0160-2896(92)90013-H.

- ^ Witelson, SF; Glezer, II; Kigar, DL (1995). "Women have greater density of neurons in posterior temporal cortex". Journal of Neuroscience 15 (5 Pt 1): 3418–28. PMID 7751921.

- ^ Kimura, Doreen (1999). Sex and Cognition. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-11236-9

- ^ Ho, K.C.; Roessmann, U.; Straumfjord, J.V.; Monroe, G. (December 1980). "Analysis of brain weight. I. Adult brain weight in relation to sex, race, and age". Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 104 (12): 635–9. PMID 6893659.

- ^ Frederikse ME, Lu A, Aylward E, Barta P, Pearlson G (December 1999). "Sex differences in the inferior parietal lobule". Cereb. Cortex 9 (8): 896–901. doi:10.1093/cercor/9.8.896. PMID 10601007. http://cercor.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=10601007.

- ^ Ellis, Lee, Sex differences: summarizing more than a century of scientific research, CRC Press, 2008, 0805859594, 9780805859591

- ^ Harasty J, Double KL, Halliday GM, Kril JJ, McRitchie DA (February 1997). "Language-associated cortical regions are proportionally larger in the female brain". Arch. Neurol. 54 (2): 171–6. PMID 9041858. http://archneur.ama-assn.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=9041858.

- ^ Brun, et al; Leporé, N; Luders, E; Chou, YY; Madsen, SK; Toga, AW; Thompson, PM (2009). "Sex differences in brain structure in auditory and cingulate regions". Neuroreport 20 (10): 930–935. doi:10.1097/WNR.0b013e32832c5e65. PMC 2773139. PMID 19562831. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2773139.

- ^ DeLacoste-Utamsing, C; Holloway, RL (1982). "Sexual dimorphism in the human corpus callosum". Science 216 (4553): 1431–1432. doi:10.1126/science.7089533. PMID 7089533.

- ^ Bishop, K; Wahlsten, D (1997). "Sex Differences in the Human Corpus Callosum: Myth or Reality?". Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 21 (5): 581–601. doi:10.1016/S0149-7634(96)00049-8. PMID 9353793.

- ^ a b Marner, L; Nyengaard, JR; Tang, Y; Pakkenberg, B. (2003). "Marked loss of myelinated nerve fibers in the human brain with age". J Comp Neurol 462 (2): 144–52. doi:10.1002/cne.10714. PMID 12794739.

- ^ Gur, Ruben C.; Bruce I. Turetsky, Mie Matsui, Michelle Yan, Warren Bilker, Paul Hughett, Raquel E. Gur (1999-05-15). "Sex Differences in Brain Gray and White Matter in Healthy Young Adults: Correlations with Cognitive Performance". The Journal of Neuroscience 19 (10): 4065–4072. PMID 10234034. http://www.jneurosci.org/cgi/content/full/19/10/4065. Retrieved 2008-05-24.

- ^ Leonard, C. M.; Towler, S.; Welcome, S.; Halderman, L. L.; Otto, R. Eckert; Chiarello, C.; Chiarello, C (2008). "Size Matters: Cerebral Volume Influences Sex Differences in Neuroanatomy". Cerebral Cortex 18 (12): 2920–2931. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhn052. PMC 2583156. PMID 18440950. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2583156.

- ^ Luders, E.; Steinmetz, H.; Jancke, L. (2002). "Brain size and grey matter volume in the healthy human brain". NeuroReport 13 (17): 2371–2374. doi:10.1097/00001756-200212030-00040. PMID 12488829.

- ^ Haier, R.J.; Jung, R.E.; Yeo, R.A.; et al. (2005). "The neuroanatomy of general intelligence: sex matters". NeuroImage 25 (1): 320–327. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.11.019. PMID 15734366.

- ^ Haier, R.J.; Jung, R.E.; Yeo, R.A.; Head, K.; Alkire, M.T. (September 2004). "Structural brain variation and general intelligence" (PDF). Neuroimage 23 (1): 425–33. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.04.025. PMID 15325390. http://www.ucihs.uci.edu/pediatrics/faculty/neurology/haier/pdf/82.pdf.

- ^ "Intelligence in men and women is a gray and white matter: Men and women use different brain areas to achieve similar IQ results, UCI study finds" University of California, Irvine. Press release. January 20, 2005.

- ^ Alonso-Nanclares, L.; Gonzalez-Soriano, J.; Rodriguez, J.R.; DeFelipe, J. (2008). "Gender differences in human cortical synaptic density". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105 (38): 14615–9. Bibcode 2008PNAS..10514615A. doi:10.1073/pnas.0803652105. PMC 2567215. PMID 18779570. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2567215.

- ^ Marano, Hara Estroff (July/August 2003). "The New Sex Scorecard". Psychology Today. http://www.psychologytoday.com/articles/PTO-20030624-000003.html.

- ^ Sex differences in the brain's serotonin system

- ^ Lopes, Alexandra M.; Ross, Norman; Close, James; Dagnall, Adam; Amorim, António; Crow, Timothy J. (2006). "Inactivation status of PCDH11X: sexual dimorphisms in gene expression levels in brain". Human Genetics 119 (3): 1–9. doi:10.1007/s00439-006-0134-0. PMID 16425037.

- ^ Arnold, A. P. (2004). "Sex chromosomes and brain gender". Nature Rev. Neurosci 5 (9): 701–708. doi:10.1038/nrn1494. PMID 15322528.

- ^ "Women nose ahead in smell tests". BBC News. 2002-02-04. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/health/1796447.stm. Retrieved 2010-05-23.

- ^ http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2005/10/051025073319.htm

- ^ Bren, Linda (July–August 2005). "Does Sex Make a Difference?". FDA Consumer magazine. http://www.fda.gov/fdac/features/2005/405_sex.html.

- ^ Howstuffworks "Red Blood Cells"

- ^ Lifestyle 'hits life length gap' BBC September 16, 2005

- ^ A Country of Widows Viktor Perevedentsev, New Times, May 2006

- ^ a b Gender, women, and health Reports from WHO 2002–2005

- ^ Marlow, Neil; Wolke, Dieter; Bracewell, Melanie A.; Samara, Muthanna; Epicure Study, Group (January 2005). "Neurologic and Developmental Disability at Six Years of Age after Extremely Preterm Birth". New England Journal of Medicine 352 (1): 9–19. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa041367. PMID 15635108.

- ^ Kraemer, S. (2000). "The fragile male : Male zygotes are often formed at suboptimal times in fertile cycle". BMJ 321 (7276): 1609–12. doi:10.1136/bmj.321.7276.1609. PMC 1119807. PMID 11124200. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1119807.

- ^ Wade, Nicholas (10 April 2007). "Pas De Deux of Sexuality is Written in the Genes". New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2007/04/10/health/10gene.html?_r=1.

- ^ Bribiescas, Richard (2008). Men: Evolutionary and Life History. ISBN 0-674-03034-6.

- ^ "Sex Ratio". The World Factbook.

Sources

- Merry, Clare V. (2005). "Pelvic Shape". Mind - Primary Cause of Human Evolution. Trafford Publishing. ISBN 1412054575. http://books.google.com/?id=mKHRUUQbt34C&pg=PA48.

- Schuenke, Michael; Schulte, Erik; Schumacher, Udo (2006). Thieme Atlas of Anatomy: General Anatomy and Musculoskeletal System. Thieme. ISBN 1-58890-419-9.

Further reading

- Geary DC (March 2006). "Sex differences in social behavior and cognition: utility of sexual selection for hypothesis generation". Horm Behav 49 (3): 273–5. doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2005.07.014. PMID 16137691. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0018-506X(05)00197-2. Full text

External links

- Brin, David (1996). "Neoteny and Two-Way Sexual Selection in Human Evolution: A Paleo-Anthropological Speculation on the Origins of Secondary-Sexual Traits, Male Nurturing and the Child as a Sexual Image". Journal of Social and Evolutionary Systems 18 (3): 257–76. doi:10.1016/1061-7361(95)90006-3. http://www.davidbrin.com/neotenyarticle1.html.: .

Human group differences Gender/Sex Gender differences | Biology of gender | Biology and sexual orientation | Sex and intelligence | Gender and crime | Sex and spatial cognition | Gender and suicide | Sex and emotion | Sex and illness | IntersexRace Other dynamics Intelligence (Neuroscience | Religiosity | Heritability of IQ | Fertility | Height | Health | Cognitive epidemiology | Blood type | Human genetic variation | Y-DNA haplogroups | Consumerism and longevity | Human penis sizeCategories:

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.