- Anterior cruciate ligament

-

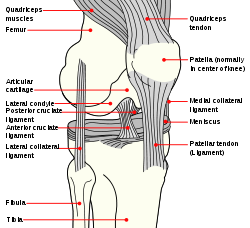

Ligament: Anterior cruciate ligament Diagram of the right knee. (Anterior cruciate ligament labeled at center left.) Latin ligamentum cruciatum anterius Gray's subject #93 342 From lateral condyle of the femur To intercondyloid eminence of the tibia Dorlands/Elsevier l_09/12492099 The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) is a cruciate ligament which is one of the four major ligaments of the human knee. In the quadruped stifle (analogous to the knee), based on its anatomical position, it is referred to as the cranial cruciate ligament.[1]

The ACL originates from deep within the notch of the distal femur. Its proximal fibers fan out along the medial wall of the lateral femoral condyle. There are two bundles of the ACL—the anteromedial and the posterolateral, named according to where the bundles insert into the tibial plateau. The ACL attaches in front of the intercondyloid eminence of the tibia, being blended with the anterior horn of the lateral meniscus. These attachments allow it to resist anterior translation and medial rotation of the tibia, in relation to the femur.

Contents

Injury

Anterior cruciate ligament injury is a common knee ligament injury, especially in athletes. Lateral rotational movements in sports like these are what cause the ACL to strain or tear. Strains can sometimes be fixed through physical therapy and muscle strengthening, though tears almost always require surgery. The most common method for repairing ACL injuries is arthroscopic surgery. Other common injuries accompanying ACL tears are meniscus, MCL, and knee cartilage tears.

Reconstructive surgery

ACL reconstructive surgery can utilize several different tendons and grafts in place of the torn ACL including the hamstring, patellar tendon, semitendinosus tendon, gracillus tendon, and the plantaris.[2] There is great controversy as to which source produces the strongest, most stable ACL replacement. Many orthopedic surgeons prefer to use tendons and grafts from cadavers; therefore the patient does not have to rehabilitate more than just their ACL. Others prefer to use tendons directly from the patient in order to counteract the potential for an immune system rejection of the cadaver tissue. Furthermore surgeons have the choice between several surgical techniques to fixate the ACL replacement to the femoral bone: staple fixation, tying sutures over buttons, and screw fixation.[3] There are several studies currently testing all the variables involved in ACL reconstructive surgery accounting for the lifestyle, age, and future goals of the ACL reconstruction patients. There are no quantitative results as to which combination of ligament and grafts work best with the different surgical techniques for every individual.

A 2010 Los Angeles Times review[4] of two seemingly conflicting medical studies discussed whether ACL reconstruction was advisable. One study found that children under 14 who had ACL reconstruction fared better after early surgery than those who underwent a delayed surgery. For adults under 35, though, patients who underwent early surgery followed by rehab fared no better than those who had rehab therapy and a later surgery.

The first report focused on children and the timing of an ACL reconstruction. ACL injuries in children, according to orthopedic surgeon Howard Luks, MD,[5] are a challenge because children have open growth plates in the bottom of the femur or thigh bone and on the top of the tibia or shin. An ACL reconstruction will typically cross the growth plates, posing a theoretical risk of injury to the growth plate, stunting leg growth or causing the leg to grow at an unusual angle.

The second study noted in the L.A. Times piece[4] focused on adults and questioned whether an ACL reconstruction was necessary when an MRI-is not merely an existing tear;[clarification needed] many patients without instability, buckling or giving way after a course of rehabilitation can be managed non-operatively. Patients involved in sports requiring significant cutting, pivoting, twisting, or rapid acceleration or deceleration may not be able to participate in these activities without ACL reconstruction, and may want to consider an early reconstruction to minimize the risk of developing common associated injuries. "You can change your knee to suit your lifestyle," says Dr. Howard Luks, "or change your lifestyle to suit your knee."

The randomized control study was also reviewed by the New York Times.[6]

The randomized control study was originally published in the New England Journal of Medicine.[7]

On Tuesday, September 13, 2011, an online article by Jim Dryden, Associate Director of Broadcast Services of the Washington University in St. Louis Newsroom Record, reviewed a Washington University School of Medicine study; the examination "looked at why second ACL surgeries often fail":

"Sports medicine specialists at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis are leading a national study analyzing why a second surgery to reconstruct a tear in the knee's anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) carries a high risk of bad outcomes.

More than 200,000 ACL reconstruction surgeries are performed each year in the united States, and 1 percent to 8 percent fail for some reason. Most of those patients then opt to have their knee ligament reconstructed a second time, but the failure rate on those subsequent surgeries is almost 14 percent.

The Washington University group has received a $2.6 million grant from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (one of the constituent institutes of the NIH, or the National Institutes of Health, which is in turn a part of the Cabinet-level U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, or USDHHS) and is leading dozens of surgeons across the nation in one of the largest orthopedic, multicenter studies ever conducted. The MARS study (Multicenter ACL Revision Study) is comparing surgical techniques and analyzing outcomes for patients undergoing ACL surgery to learn why a subsequent reconstruction is more likely to fail than an initial ACL repair."[8]

Additional images

See also

- Lateral collateral ligament

- Medial collateral ligament

- Posterior cruciate ligament

- Anterior drawer test

- Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction

References

- ^ "Canine Cranial Cruciate Ligament Disease" (pdf). Melbourne Veterinary Referral Centre. pp. 1–2. http://www.melbvet.com.au/pdf/cruciate-disease.pdf. Retrieved September 8, 2009.[dead link]

- ^ Saladin, Kenneth S. Anatomy and Physiology: The Unity of Form and Function. Boston: McGraw Hill, 2010

- ^ Kurasaka, Yoshiya, and Andrish. A biomechanical comparison of different surgical techniques of graft fixation in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. The Americancanadian Journal of Sports Medicine. June 1987

- ^ a b Stein, Jeannine (2010-07-22). "Studies on ACL surgery". The Los Angeles Times. http://www.latimes.com/news/health/boostershots/la-heb-0721-acl-20100721,0,5649792.story. Retrieved 2010-07-23.

- ^ "ACL Tears: To reconstruct or not, and if so, when?". howardluksmd.com. http://www.howardluksmd.com/journal/2010/7/23/anterior-cruciate-ligament-acl-tears-to-reconstruct-or-not-a.html. Retrieved 2010-07-23.

- ^ Reynolds, Gretchen (2010-08-04). "How much does knee surgery really help?". New York Times. http://well.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/08/04/phys-ed-how-much-does-knee-surgery-really-help/?scp=3&sq=acl&st=cse.

- ^ Frobell, Richard B.; Roos, Ewa M.; Roos, Harald P.; Ranstam, Jonas; Lohmander, L. Stefan (2010). "A Randomized Trial of Treatment for Acute Anterior Cruciate Ligament Tears". New England Journal of Medicine 363 (4): 331–342. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0907797. PMID 20660401. http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa0907797.

- ^ http://news.wustl.edu/news/Pages/22661.aspx

External links

- SUNY Labs 17:02-0701 - "Major Joints of the Lower Extremity: Knee Joint"

- SUNY Figs 17:07-08 - "Superior view of the tibia."

- SUNY Figs 17:08-03 - "Medial and lateral views of the knee joint and cruciate ligaments."

- lljoints at The Anatomy Lesson by Wesley Norman (Georgetown University) (antkneejointopenflexed)

Joints and ligaments of lower limbs (TA A03.6, GA 3.333) Coxal/hip femoral (iliofemoral, pubofemoral, ischiofemoral) · head of femur · transverse acetabular · acetabular labrum · capsule · zona orbicularisKnee-joint TibiofemoralCapsule · Anterior meniscofemoral ligament · Posterior meniscofemoral ligament

extracapsular: popliteal (oblique, arcuate) · collateral (medial/tibial, fibular/lateral)

intracapsular: cruciate (anterior, posterior) · menisci (medial, lateral) · transversePatellofemoralTibiofibular Superior tibiofibularInferior tibiofibularJoints of foot medial: medial of talocrural joint/deltoid (anterior tibiotalar, posterior tibiotalar, tibiocalcaneal, tibionavicular)

lateral: lateral collateral of ankle joint (anterior talofibular, posterior talofibular, calcaneofibular)Distal intertarsalOtherM: JNT

anat(h/c, u, t, l)/phys

noco(arth/defr/back/soft)/cong, sysi/epon, injr

proc, drug(M01C, M4)

Categories:- Ligaments of the lower limb

- Knee

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.