- Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade

-

This article is about the film. For the video games, see Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (video game).

Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade

Theatrical poster by Drew StruzanDirected by Steven Spielberg Produced by Robert Watts Screenplay by Jeffrey Boam

Uncredited:

Tom StoppardStory by George Lucas

Menno MeyjesStarring Harrison Ford

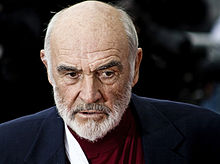

Sean Connery

Alison Doody

Denholm Elliott

Julian Glover

River Phoenix

John Rhys-DaviesMusic by John Williams Cinematography Douglas Slocombe Editing by Michael Kahn Studio Lucasfilm Ltd. Distributed by Paramount Pictures Release date(s) May 24, 1989 Running time 127 minutes Country United States Language English Budget $48,000,000 Box office $474,171,806 Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade is a 1989 American adventure film directed by Steven Spielberg, from a story co-written by executive producer George Lucas. It is the third film in the Indiana Jones franchise. Harrison Ford reprises the title role and Sean Connery plays Indiana's father, Henry Jones, Sr. Alison Doody, Denholm Elliott, Julian Glover, River Phoenix, and John Rhys-Davies also have featured roles. In the film, set largely in 1938, Indiana searches for his father, a Holy Grail scholar, who has been kidnapped by Nazis.

After the mixed reaction to the dark Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, Spielberg chose to compensate by completing the trilogy with a film lighter in tone. During the five years between Temple of Doom and Last Crusade, he and executive producer Lucas reviewed several scripts before accepting Jeffrey Boam's. Filming locations included Spain, Italy, England, Turkey and Jordan.

The film was released in North America on May 24, 1989 to mostly positive reviews. It was a financial success, earning $474,171,806 at the worldwide box office totals. It won the Academy Award for Best Sound Editing.

Contents

Plot

In 1912, 13-year-old Indiana Jones is horseback riding with his Boy Scout troop in Utah. He discovers robbers in a cave who find an ornamental cross which belonged to Coronado and steals the cross from them. As they give chase, Indiana hides in a circus train. Although he escapes, the robbers bring the sheriff, and Indiana is forced to return it. Meanwhile, his oblivious father, Henry Jones, Sr., is working on his research into the Holy Grail, keeping meticulous notes in a diary. The leader of the hired robbers, dressed very similarly to the future Indiana and impressed by the young Indiana's tenacity, gives him his fedora and some encouraging words.

In 1938, after recovering the cross and donating it to Marcus Brody's museum, Indiana is introduced to Walter Donovan, who informs him that Indiana's estranged father has vanished while searching for the Holy Grail, using an incomplete inscription as his guide. Indiana then receives a package by post which turns out to be his father's Grail diary, containing his father's research. Understanding that his father would not have sent the diary unless he was in trouble, Indiana and Marcus travel to Venice, where they meet Henry's colleague, Dr. Elsa Schneider. Beneath the library where Henry was last seen, Indiana and Elsa discover catacombs and the tomb of a knight of the First Crusade, which also contains a complete version of the inscription that Henry had used, this one revealing the location of the Grail. They flee when the catacombs are set aflame by The Brotherhood of the Cruciform Sword, a secret society. Indiana and Elsa are pursued and escape on a speedboat, and a chase through Venice ensues in which they capture the secret society's leader, Kazim. After Indiana convinces him of their legitimate intentions, Kazim explains that The Brotherhood are protecting the Grail from those with evil intentions, and that Henry was abducted to Brunwald Castle on the Austrian-German border.

Indiana infiltrates the castle and finds his father, but learns that Elsa and Donovan are working with the Nazis, hoping that Indiana would discover the location of the Grail for them. The Nazis capture Marcus, who had traveled to Hatay, Turkey with a map that Henry had drawn to show the route to the Grail's hiding place. The Joneses are able to escape and recover the diary from Elsa at a Nazi rally in Berlin while barely escaping possible arrest by Adolf Hitler. On a Zeppelin and later a plane they escape from Germany. They then meet Sallah in Hatay, where they learn of Marcus' abduction and that the Nazis are already moving to the Grail's location. With the help of The Brotherhood, the Joneses ambush the Nazi convoy and rescue Marcus. Donovan and Elsa continue on to the Canyon of the Crescent Moon, the location of the Grail.

Indiana, Henry, Marcus, and Sallah catch up and find that the Nazis are unable to pass through traps set before the Grail. After the four are discovered, Donovan shoots Henry, mortally wounding him, and thus forces Indiana ("The healing power of the grail is the only thing that can save your father now") to circumvent the traps by using the information in his father's diary, with Donovan and Elsa following. Indiana succeeds and finds himself in a room with the last Knight, kept alive with the power of the Grail, which has been hidden among dozens of other cups. Elsa selects a gilded cup encrusted in jewels for Donovan; when Donovan drinks from it, he rapidly decays and crumbles into dust. Indiana, recognizing that the Grail would be that of a humble carpenter instead of a wealthy king, selects the plainest-looking cup in the group, which turns out to be the correct vessel. He fills it with water and quickly takes it to his father and pours the holy water onto his chest, which instantly heals his gunshot wound. As they prepare to leave, the Knight warns them to not take the Grail past the great seal in the temple's floor, but Elsa disobeys, causing the temple to collapse. Elsa falls into an abyss while attempting to recover the Grail; Indiana nearly suffers the same fate until his father tells him to let it go. The Joneses, Marcus, and Sallah narrowly escape the collapsing temple. The four then ride out of the canyon, and into the sunset.

Cast

- Harrison Ford as Dr. Indiana Jones

- Sean Connery as Professor Henry Jones

- Denholm Elliott as Dr. Marcus Brody

- Alison Doody as Dr. Elsa Schneider

- John Rhys Davies as Sallah

- Julian Glover as Walter Donovan

- River Phoenix as Indiana Jones (aged 13)

- Michael Byrne as SS-Standartenführer (Colonel) Ernst Vogel

- Kevork Malikyan as Kazim

- Robert Eddison as the Grail Knight

- Vernon Dobtcheff as the Butler

Production

Development

Lucas and Spielberg had intended to make a trilogy of Indiana Jones films since Lucas had first pitched Raiders of the Lost Ark to Spielberg in 1977.[1] After the mixed critical and public reaction to Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, Spielberg decided to complete the trilogy to fulfill his promise to Lucas and "to apologize for the second one".[2] The pair had the intention of revitalizing the series by evoking the spirit and tone of Raiders of the Lost Ark.[3] Throughout development and pre-production of The Last Crusade, Spielberg admitted he was "consciously regressing" in making the film.[4] Due to his commitment to The Last Crusade, the director had to drop out of directing Big and Rain Man.[1]

Lucas initially suggested making the film "a haunted mansion movie", for which Romancing the Stone writer Diane Thomas wrote a script. Spielberg rejected the idea because of the similarity to Poltergeist, which he had co-written and produced.[4] Lucas first introduced the Holy Grail in an idea for the film's prologue, which was to be set in Scotland. He intended the Grail to have a pagan basis, with the rest of the film revolving around a separate Christian artifact in Africa. Spielberg did not care for the Grail idea, which he found too esoteric,[5] even after Lucas suggested giving it healing powers and the ability to grant immortality. In September 1984 Lucas completed an eight-page treatment titled Indiana Jones and the Monkey King, which he soon followed with an 11-page outline. The story saw Indiana battling a ghost in Scotland before finding the Fountain of Youth in Africa.[6]

Chris Columbus—who had written the Spielberg-produced Gremlins, The Goonies, and Young Sherlock Holmes—was hired to write the script. His first draft, dated May 3, 1985, changed the main plot device to a Garden of Immortal Peaches. It begins in 1937, with Indiana battling the murderous ghost of Baron Seamus Seagrove III in Scotland. Indiana travels to Mozambique to aid Dr. Clare Clarke (a Katharine Hepburn type, according to Lucas) who has found a 200-year-old pygmy. The pygmy is kidnapped by the Nazis during a boat chase, and Indiana, Clare and Scraggy Brier—an old friend of Indiana—travel up the Zambesi river to rescue him. Indiana is killed in the climactic battle but is resurrected by the Monkey King. Other characters include a cannibalistic African tribe; Nazi Sergeant Gutterbuhg, who has a mechanical arm; Betsy, a stowaway student who is suicidally in love with Indiana; and a pirate leader named Kezure (described as a Toshirō Mifune type), who dies eating a peach because he is not pure of heart. The tank is three stories high and requires Indiana to ride a rhinoceros to commandeer it.[6]

Columbus's second draft, dated August 6, 1985, removed Betsy and featured Dash — an expatriate bar owner working for the Nazis — and the Monkey King as villains. The Monkey King forces Indiana and Dash to play chess with real people and disintegrates each person who is captured. Indiana subsequently battles the undead, destroys the Monkey King's rod, and marries Clare.[6] Location scouting commenced in Africa but Spielberg and Lucas abandoned Monkey King because of its negative depiction of African natives,[7] and because the script was unrealistic.[6] Spielberg acknowledged that it made him "...feel very old, too old to direct it."[5] Columbus's script was leaked onto the Internet in 1997, and many believed it was an early draft for the fourth film because it was mistakenly dated to 1995.[8]

Unsatisfied, Spielberg suggested introducing Indiana's father, Henry Jones, Sr. Lucas was dubious, believing the Grail should be the focus of the story, but Spielberg convinced him that the father–son relationship would serve as a great metaphor in Indiana's search for the artifact.[4] Spielberg hired Menno Meyjes, who had worked on Spielberg's The Color Purple and Empire of the Sun, to begin a new script on January 1, 1986. Meyjes completed his script ten months later. It depicted Indiana searching for his father in Montségur, where he meets a nun named Chantal. Indiana travels to Venice, takes the Orient Express to Istanbul, and continues by train to Petra, where he meets Sallah and reunites with his father. In the denouement, the Nazis touch the Grail and explode; when Henry touches it, he ascends a staircase into Heaven. Chantal chooses to stay on Earth and marries Indiana. In a revised draft dated two months later, Indiana finds his father in Krak des Chevaliers, the Nazi leader is a woman named Greta von Grimm, and Indiana battles a demon at the Grail site, which he defeats with a dagger inscribed with "God is King". The prologue in both drafts has Indiana in Mexico battling for possession of Montezuma[disambiguation needed

]'s mask with a man who owns gorillas as pets.[6]

]'s mask with a man who owns gorillas as pets.[6] Indiana Jones (River Phoenix) finds the Cross of Coronado as a 13-year-old Boy Scout. Spielberg suggested making Indiana a Boy Scout as both he and Harrison Ford were former Scouts.

Indiana Jones (River Phoenix) finds the Cross of Coronado as a 13-year-old Boy Scout. Spielberg suggested making Indiana a Boy Scout as both he and Harrison Ford were former Scouts.

Spielberg suggested Innerspace writer Jeffrey Boam perform the next rewrite. Boam spent two weeks reworking the story with Lucas.[6] Boam told Lucas that Indiana should find his father in the middle of the story. "Given the fact that it's the third film in the series, you couldn't just end with them obtaining the object. That's how the first two films ended," he said, "So I thought, let them lose the Grail, and let the father–son relationship be the main point. It's an archaeological search for Indy's own identity and coming to accept his father is more what it's about [than the quest for the Grail]."[4] Boam said he felt there was not enough character development in the previous films.[5] In Boam's first draft, dated September 1987, the film is set in 1939. The prologue has Indiana retrieving an Aztec relic for a professor in Mexico and features the circus train. The leader of the Brotherhood of the Cruciform Sword is Kemal, a Hatayan secret agent who allies with the Nazis because he wants the Grail for the glory of his country. He shoots Henry and dies drinking from the wrong chalice. Henry and Elsa (who is described as having dark hair) were searching for the Grail on behalf of the Chandler Foundation. The Grail Knight battles Indiana on horseback, while Vogel is crushed by a boulder when stealing the Grail.[6]

Boam's February 1988 rewrite utilized many of Connery's comic suggestions. It included the prologue that was eventually filmed; Lucas had to convince Spielberg to show Indiana as a boy because of the mixed response to Empire of the Sun, which was about a young boy.[5] Spielberg—who was later awarded the Distinguished Eagle Scout Award—had the idea of making Indiana a Boy Scout.[1] Indiana's mother, named Margaret in this version, dismisses Indiana when he returns home with the Cross of Coronado, while his father is on a long distance call. Walter Chandler of the Chandler Foundation features, but is not the main villain; he plunges to his death in the tank. Elsa shoots Henry, then dies drinking from the wrong Grail, and Indiana rescues his father from falling into the chasm while grasping for the Grail. Vogel is beheaded by the traps guarding the Grail, while Kemal tries to blow up the temple during a comic fight in which gunpowder is repeatedly lit and extinguished. Leni Riefenstahl appears at the Nazi rally.[6] Boam's revision the following month showed Henry causing the seagulls to strike the plane. Tom Stoppard rewrote the script by May 8, 1988 under the pen name Barry Watson.[6] He polished much of the dialogue,[9] and created the "Panama Hat" character to link the segments of the prologue featuring the young and adult Indianas. Stoppard also renamed Kemal to Kazim and Chandler to Donovan, and made Donovan shoot Henry.[6]

Filming

Principal photography began on May 16, 1988 in the Tabernas Desert in the Almería province of Spain. Spielberg originally had planned the chase to be a short sequence shot over two days, but he drew up storyboards to make the scene an action-packed centerpiece.[3] Thinking he would not surpass the truck chase from Raiders of the Lost Ark (because the truck was much faster than the tank), he felt this sequence should be more story-based and needed to show Indiana and Henry helping each other. He later said he had more fun storyboarding the sequence than filming it.[10] The second unit had begun filming two weeks before.[11] After approximately ten days the production moved to Bellas Artes to film the scenes set in the Sultan of Hatay's palace. Cabo de Gata-Níjar Natural Park was used for the road, tunnel and beach sequence in which birds strike the plane. The Spanish portion of the shoot wrapped on June 2, 1988 in Guadix, Granada with filming of Brody's capture at İskenderun train station.[11] The filmmakers built a mosque near the station for atmosphere, rather than adding it as a visual effect.[10]

Filming for the castle interiors took place from June 5 to 10, 1988 at Elstree Studios, England. The fire was filmed last. On June 16, the Royal Horticultural Society was used for the airport interiors. Filming returned to Elstree the next day to capture the motorcycle escape, continuing at the studio for interior scenes until July 18. One day was spent at North Weald Airfield on June 29 to film Indiana leaving for Venice.[11] Ford and Connery acted much of the Zeppelin table conversation without trousers on because of the overheated set.[12] Spielberg, Marshall and Kennedy interrupted the shoot to make a plea to the Parliament of the United Kingdom to support the economically "depressed" British studios. July 20–22 was spent filming the temple interiors. The temple set, which took six weeks to build, was supported on 80 feet of hydraulics and ten gimbals for use during the earthquake scene. Resetting between takes took twenty minutes while the hydraulics were put to their starting positions and the cracks filled with plaster. The shot of the Grail falling to the temple floor—causing the first crack to appear—was attempted on the full-size set, but proved too difficult. Instead, crews built a separate floor section that incorporated a pre-scored crack sealed with plaster. It took several takes to throw the Grail from six feet onto the right part of the crack.[10] July 25–26 was spent on night shoots at Stowe School, Stowe, Buckinghamshire for the Nazi rally.[11]

Filming resumed two days later at Elstree, where Spielberg swiftly filmed the library, Portuguese freighter, and catacombs sequences.[11] The steamship fight in the 1938 portion of the prologue was filmed in three days on a sixty-by-forty-feet deck built on gimbals at Elstree. A dozen dump tanks—each holding three hundred imperial gallons (360 U.S. gallons; 3000 lb) of water—were used in the scene.[10] Henry's house was filmed at Mill Hill, London. Indiana and Kazim's fight in Venice in front of a ship's propeller was filmed in a water tank at Elstree. Spielberg used a long focus lens to make it appear the actors were closer to the propeller than they really were.[11] Two days later, on August 4, another portion of the boat chase using Hacker Craft sport boats, was filmed at Tilbury Docks in Essex.[11] The shot of the boats passing between two ships was achieved by first cabling the ships off so they would be safe. The ships were moved together while the boats passed between, close enough that one of the boats scraped the sides of the ships. An empty speedboat containing dummies was launched from a floating platform between the ships amid fire and smoke that helped obscure the platform. The stunt was performed twice because the boat landed too short of the camera in the first attempt.[10] The following day, filming in England wrapped at the Royal Masonic School in Rickmansworth, which doubled for Indiana's college (as it had in Raiders of the Lost Ark).[11]

Al Khazneh was used for the entrance to the temple housing the Holy Grail

Shooting in Venice took place on August 8.[11] For scenes such as Indiana and Brody greeting Elsa, shots of the boat chase, and Kazim telling Indiana where his father is,[10] Robert Watts gained control of the Grand Canal from 7 am to 1 pm, sealing off tourists for as long as possible. Cinematographer Douglas Slocombe positioned the camera to ensure no satellite dishes would be visible.[11] San Barnaba di Venezia served as the exterior to the library.[3] The next day, filming moved to the ancient city of Petra, Jordan, which stood in for the temple housing the Grail. The cast and crew became guests of King Hussein and Queen Noor. The main cast completed their scenes that week, after 63 days of filming.[11]

The second unit filmed part of the 1912 segment of the prologue from August 29 to September 3. The main unit began two days later with the circus train sequence at Alamosa, Colorado. They filmed at Pagosa Springs on September 7, and then at Cortez on September 10. From September 14 to 16, filming of Indiana falling into the train carriages took place in Los Angeles. The production then moved to Arches National Park in Utah to shoot more of the opening. A house near the park was used for the Jones family home.[11] The production had intended to film at Mesa Verde National Park, but Native American representatives had religious objections to its use.[10] When Spielberg and editor Michael Kahn viewed a rough cut of the film in late 1988, they felt it suffered from a lack of action. The motorcycle chase was shot during post-production at Mount Tamalpais and Fairfax near Skywalker Ranch. The closing shot of Indiana, Henry, Sallah and Brody riding into the sunset was filmed in Texas in early 1989.[11][13]

Design

Mechanical effects supervisor George Gibbs said The Last Crusade was the most difficult film of his career.[10] He visited a museum to negotiate renting a small French World War I tank, but decided he wanted to make one.[11] The tank was based on the Tank Mark VIII, which was 36 feet and 28 tons. Gibbs built the tank over the framework of a 28-ton excavator and added seven ton tracks that were driven by two automatic hydraulic pumps, each connected to a Range Rover V8 engine. Gibbs built the tank from steel rather than aluminum or fiberglass because it would allow the realistically suspensionless vehicle to endure the rocky surfaces. Unlike its historical counterpart—which had four side guns—the tank had a turret and two guns on its sides. It took four months to build and was transported to Almería on a Short Belfast plane and then a low loader truck.[10]

The tank broke down twice. The rotor arm in the distributor broke and a replacement had to be sourced from Madrid. Then two of the valves in the device used to cool the oil exploded, due to solder melting and mixing with the oil. It was very hot in the tank, despite the installation of ten fans, and the lack of suspension meant the driver was unable to stop shaking during filming breaks.[10] The tank only moved at ten to twelve miles per hour, which Vic Armstrong said made it difficult to film Indiana riding a horse against the tank while making it appear faster.[11] A smaller section of the tank's top made from aluminum and which used rubber tracks was used for close-ups. It was built from a searchlight trailer, weighed eight tons, and was towed by a four-wheel drive truck. It had safety nets on each end to prevent injury to those falling off.[10] A quarter-scale model by Gibbs was driven over a 50-foot (15 m) cliff on location; Industrial Light & Magic created further shots of the tank's destruction with models and miniatures.[14]

Michael Lantieri, mechanical effects supervisor for the 1912 scenes, noted the difficulty in shooting the train sequence. "You can't just stop a train," he said, "If it misses its mark, it takes blocks and blocks to stop it and back up." Lantieri hid handles for the actors and stuntmen to grab onto when leaping from carriage to carriage. The carriage interiors shot at Universal Studios Hollywood were built on tubes that inflated and deflated to create a rocking motion.[10] For the close-up of the rhinoceros that strikes at (and misses) Indiana, a foam and fiberglass animatronic was made in London. When Spielberg decided he wanted it to move, the prop was sent to John Carl Buechler in Los Angeles, who resculpted it over three days to blink, snarl, snort and wiggle its ears. The giraffes were also created in London. Because steam locomotives are very loud, Lantieri's crew would respond to first assistant director David Tomblin's radioed directions by making the giraffes nod or shake their heads to his questions, which amused the crew.[14] For the villains' cars, Lantieri selected a 1912 Ford Model A and a 1914 Saxon, fitting each with a Ford Pinto V6 engine. Sacks of dust were hung under the cars to create a dustier environment.[10]

Spielberg used doves for the seagulls that Henry scares into striking the German plane because the real gulls used in the first take did not fly.[3] In December 1988, Lucasfilm ordered 1000 disease-free gray rats for the catacombs scenes from the company that supplied the snakes and bugs for the previous films. Within five months, 5000 rats had been bred for the sequence;[3] 1000 mechanical rats stood in for those that were set on fire. Several thousand snakes of five breeds—including a boa constrictor—were used for the train scene, in addition to rubber ones onto which Phoenix could fall. The snakes would slither from their crates, requiring the crew to dig through sawdust after filming to find and return them. Two lions were used, which became nervous because of the rocking motion and flickering lights.[10]

Costume designer Anthony Powell found it a challenge to create Connery's costume because the script required the character to wear the same clothes throughout. Powell thought about his own grandfather and incorporated tweed suits and fishing hats. Powell felt it necessary for Henry to wear glasses, but did not want to hide Connery's eyes, so chose rimless ones. He could not find any suitable, so he had them specially made. The Nazi costumes were genuine and were found in Eastern Europe by Powell's co-designer Joanna Johnston, to whom he gave research pictures and drawings for reference.[11]

Gibbs used Swiss army training planes for the German planes. He built a device based on an internal combustion engine to simulate gunfire, which was safer and less expensive than firing blanks.[14] Baking soda was applied to Connery to create Henry's bullet wound. Vinegar was applied to create the foaming effect as the water from the Grail washes it away.[14]

Effects

Industrial Light & Magic (ILM) built an eight-foot foam model of the Zeppelin to complement shots of Ford and Connery climbing into the biplane. A biplane model with a two-foot wingspan was used for the shot of the biplane detaching. Stop motion animation was used for the shot of the German fighter's wings breaking off as it crashes through the tunnel. The tunnel was a 210 feet model that occupied 14 of ILM's parking spaces for two months. It was built in eight-foot sections, with hinges allowing each section to be opened to film through. Ford and Connery were filmed against bluescreen; the sequence required their car to have a dirty windscreen, but to make the integration easier this was removed and later composited into the shot. Dust and shadows were animated onto shots of the plane miniature to make it appear as if it disturbed rocks and dirt before it exploded. Several hundred tim-birds were used in the background shots of the seagulls striking the other plane; for the closer shots, ILM dropped feather-coated crosses onto the camera. These only looked convincing because the scene's quick cuts merely required shapes that suggested gulls.[14]

Indiana discovers a bridge hidden by forced perspective. Ford was filmed in front of a bluescreen for the scene, which was completed by a model of the bridge filmed against a matte painting

Indiana discovers a bridge hidden by forced perspective. Ford was filmed in front of a bluescreen for the scene, which was completed by a model of the bridge filmed against a matte painting

Spielberg devised the three trials that guard the Grail.[5] For the first, the blades under which Indiana ducks like a penitent man were a mix of practical and miniature blades created by Gibbs and ILM. For the second trial, in which Indiana spells "Iehovah" on stable stepping stones, it was intended to have a tarantula crawl up Indiana after he mistakenly steps on "J". This was filmed and deemed unsatisfactory, so ILM filmed a stuntman hanging through a hole that appears in the floor, 30 feet above a cavern. As this was dark, it did not matter that the matte painting and models were rushed late in production. The third trial, the leap of faith that Indiana makes over an apparently impassable ravine after discovering a bridge hidden by forced perspective, was created with a model bridge and painted backgrounds. This was cheaper than building a full-size set. A puppet of Ford was used to create a shadow on the 9-foot-tall (2.7 m) by 13-foot-wide (4.0 m) model because Ford had filmed the scene against bluescreen, which did not incorporate the shaft of light from the entrance.[14]

Spielberg wanted Donovan's death shown in one shot, so it would not look like an actor having makeup applied between takes. Inflatable pads were applied to Julian Glover's forehead and cheeks that made his eyes seem to recede during the character's initial decomposing, as well as a mechanical wig that grew his hair. The shot of Donovan's death was created over three months by morphing together three puppets of Donovan in separate stages of decay, a technique ILM mastered on Willow (1988).[12] A fourth puppet was used for the decaying clothes, because the puppet's torso mechanics had been exposed. Complications arose because Allison Doody's double had not been filmed for the latter two elements of the scene, so the background and hair from the first shot had to be used throughout, with the other faces mapped over it. Donovan's skeleton was hung on wires like a marionette; it required several takes to film it crashing against the wall because not all the pieces released upon impact.[14]

Ben Burtt designed the sound effects. He recorded chickens for the sounds of the rats,[11] and digitally manipulated the noise made by a Styrofoam cup for the castle fire. He rode in a biplane to record the sounds for the dogfight sequence, and visited the demolition of a wind turbine for the plane crashes.[14] Burtt wanted an echoing gunshot for Donovan wounding Henry, so he fired a .357 Magnum in Skywalker Ranch's underground car park, just as Lucas drove in.[11] A rubber balloon was used for the earthquake tremors at the temple.[15] The Last Crusade was released in selected theaters in the 70 mm Full-Field Sound format, which allowed sounds to not only move from side to side, but also from the front to the rear of the theater.[14]

Matte paintings of the Austrian castle and German airport were based on real buildings; the Austrian castle was a small West German castle that was made to look larger. Rain was created by filming granulated Borax soap against black at high speed. It was only lightly double exposed into the shots so it would not resemble snow. The lightning was animated. The airport used was at San Francisco's Treasure Island, which already had appropriate art deco architecture. ILM added a control tower, Nazi banners, vintage automobiles and a sign stating "Berlin Flughafen". The establishing shot of the Hatayan city at dusk was created by filming silhouetted cutouts that were backlit and obscured by smoke. Matte paintings were used for the sky and to give the appearance of fill light in the shadows and rim light on the edges of the buildings.[14]

Themes

A son's relationship with his estranged father is a common theme in Spielberg's films, including E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial and Hook.[4]

The Last Crusade's exploration of fathers and sons coupled with its use of religious imagery is comparable to two other 1989 films, Star Trek V: The Final Frontier and Field of Dreams. Writing for The New York Times, Caryn James felt the combination in these films reflected New Age concerns, where the worship of God was equated to searching for fathers. James felt neither Indiana or his father are preoccupied with finding the Grail or defeating the evil Nazis, but finding a professional respect for one another on their boys' own adventure. James contrasted the biblical destruction of the temple with the more effective and quiet conversation between the Joneses at the end of the film. James noted Indiana's mother is not in the prologue and stated to have died by the events of the film.[16]

Cultural references

The 1912 prologue refers to events in the lives of Indiana's creators. When Indiana cracks the bullwhip to defend himself against a lion, he accidentally lashes and scars his chin. Ford gained this scar in a car accident as a young man.[3] Indiana taking his nickname from his pet Alaskan Malamute is a reference to the character being named after Lucas's dog.[12] The train carriage Indiana enters is named "Doctor Fantasy's Magic Caboose", which was the name producer Frank Marshall used when performing magic tricks. Spielberg suggested the idea, Marshall came up with the false-bottomed box through which Indiana escapes,[17] and production designer Elliott Scott suggested the trick be done in a single, uninterrupted shot.[10] Spielberg intended the shot of Henry with his umbrella—after he causes the bird strike on the German plane—to evoke Ryan's Daughter.[12]

There is also a special reference made to the Nazi book burnings when Indiana Jones Jr, along with Indiana Jones Sr, escape from the clutches of Mr. Donovan and attempt to recover the Grail Diary from Berlin. Harrison Ford also makes an appealing statement when he recovers the book from Dr. Elsa Schneider, where he states, He would rather save books than "incinerate" them. His father offers an even stronger protest. When a Nazi officer does not understand Jones' Grail Diary clues, he asks, "What does the diary tell you that it doesn't tell us?" To which the elder Jones fires back, "It tells me...that goose-stepping morons like yourself should try READING books instead of BURNING them!"

Release

Marketing

The teaser trailer for The Last Crusade debuted in November 1988 with Scrooged and The Naked Gun.[18] Rob MacGregor wrote the tie-in novelization that was released in June 1989;[19] it sold enough copies to be included on the New York Times Best Seller list.[20] MacGregor went on to write the first six Indiana Jones prequel novels during the 1990s. Following the film's release, Ford donated Indiana's fedora and jacket to the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of American History.[21]

No toys were made to promote The Last Crusade; Indiana Jones "never happened on the toy level", said Larry Carlat, senior editor of the journal Children's Business. Rather, Lucasfilm promoted Indiana as a lifestyle symbol, selling tie-in fedoras, shirts, jackets and watches.[22] Two video games based on the film were released by LucasArts in 1989: Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade: The Graphic Adventure and Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade: The Action Game. A third game was produced by Taito and released in 1991 for the Nintendo Entertainment System. Ryder Windham wrote another novelization, released in April 2008 by Scholastic, to coincide with the release of Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (2008). Hasbro released toys based on The Last Crusade in July 2008.[23]

Box office

Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade was released in North America on May 24, 1989 in 2,327 theaters, earning $29,355,021 in its opening weekend.[24] This was the third-highest opening weekend of 1989, behind Ghostbusters II and Batman.[25] Its opening day gross of $11,181,429 was the first time a film had made over $10 million on its first day. It broke the record for the best six-day performance, with almost $47 million, added another record with $77 million after twelve days, and $100 million in nineteen days. It grossed $195.7 million by the end of the year and $450 million worldwide by March 1990.[11] In France, the film broke a record by selling a million admissions within two and a half weeks.[21]

The film eventually grossed $197,171,806 in North America and $277 million internationally, for a worldwide total of $474,171,806. At the time of its release, The Last Crusade was the 11th highest-grossing film of all time.[24] Despite competition from Batman, The Last Crusade became the highest-grossing film worldwide in 1989.[26] In North America, Batman took top position.[25] Behind Kingdom of the Crystal Skull and Raiders, The Last Crusade is the third-highest grossing Indiana Jones film in North America, though it is also behind Temple of Doom when adjusting for inflation.[27]

Reviews

The Last Crusade opened to mixed reviews. It was panned by Andrew Sarris in The New York Observer, David Denby in New York magazine, Stanley Kauffmann in The New Republic and Georgia Brown in The Village Voice.[11] Jonathan Rosenbaum of the Chicago Reader called the film "soulless".[28] The Washington Post reviewed the film twice; Hal Hinson's review on the day of the film's release was negative, describing it as "nearly all chases and dull exposition". Although he praised Ford and Connery, he felt the film's exploration of Indiana's character took away his mystery and that Spielberg should not have tried to mature his storytelling.[29] Two days later, Desson Thomson published a positive review praising the film's adventure and action, as well as the thematic depth of the father–son relationship.[30] Joseph McBride of Variety observed the "Cartoonlike Nazi villains of Raiders have been replaced by more genuinely frightening Nazis led by Julian Glover and Michael Byrne," and found the moment where Indiana meets Hitler "chilling".[31] In his biography of Spielberg, McBride added the film was less "racist" than its predecessors.[4]

Peter Travers of Rolling Stone said the film was "the wildest and wittiest Indy of them all". Richard Corliss of Time and David Ansen of Newsweek praised it, as did Vincent Canby of The New York Times.[11] "Though it seems to have the manner of some magically reconstituted B-movie of an earlier era, The Last Crusade is an endearing original," Canby wrote, deeming the revelation Indiana had a father he was not proud of to be a "comic surprise". Canby believed that while the film did not match the previous two in its pacing, it still had "hilariously off-the-wall sequences" such as the circus train chase. He also said that Spielberg was maturing by focusing on the father–son relationship,[32] a call echoed by McBride in Variety.[31] Roger Ebert praised the scene depicting Indiana as a Boy Scout with the Cross of Coronado; he compared it to the "style of illustration that appeared in the boys' adventure magazines of the 1940s", saying that Spielberg "must have been paging through his old issues of Boys' Life magazine... the feeling that you can stumble over astounding adventures just by going on a hike with your Scout troop. Spielberg lights the scene in the strong, basic colors of old pulp magazines."[33] The Hollywood Reporter felt Connery and Ford deserved Academy Award nominations.[11]

The film was evaluated positively after its release. Internet reviewer James Berardinelli wrote that while the film did not reach the heights of Raiders of the Lost Ark, it "[avoided] the lows of The Temple of Doom. A fitting end to the original trilogy, Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade captures some of the sense of fun that infused the first movie while using the addition of Sean Connery to up the comedic ante and provide a father/son dynamic."[34] Neil Smith of the BBC praised the action, but said the drama and comedy between the Joneses was more memorable. He noted, "The emphasis on the Jones boys means Julian Glover's venal villain and Alison Doody's treacherous beauty are sidelined, while the climax [becomes] one booby-trapped tomb too many."[35] Based on 55 reviews listed by Rotten Tomatoes, 89% of critics praised The Last Crusade, giving it an average score of 8/10.[36] Metacritic calculated an average rating of 65/100, based on 14 reviews.[37]

Impact

The film won the Academy Award for Best Sound Editing; it had also received nominations for Best Original Score and Best Sound (Ben Burtt, Gary Summers, Shawn Murphy and Tony Dawe), but lost to The Little Mermaid and Glory respectively.[38] Sean Connery received a Golden Globe Award nomination for Best Supporting Actor.[39] Connery and the visual and sound effects teams were also nominated at the 43rd British Academy Film Awards.[40] The Last Crusade won the 1990 Hugo Award for Best Dramatic Presentation,[41] and was nominated for Best Motion Picture Drama at the Young Artist Awards.[42] John Williams' score won a BMI Award, and was nominated for a Grammy Award.[43]

The prologue depicting Indiana in his youth inspired Lucas to create The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles television show, which featured Sean Patrick Flanery as the young adult Indiana and Corey Carrier as the 8–10 year-old Indiana.[13] The 13-year-old incarnation played by Phoenix in the film was the focus of a Young Indiana Jones series of young adult novels that began in 1990;[44] by the ninth novel, the series had become a tie-in to the television show.[45] German author Wolfgang Hohlbein revisited the 1912 prologue in one of his novels, in which Indiana encounters the lead grave robber—whom Hohlbein christens Jake—in 1943.[46] The film's ending begins the 1995 comic series Indiana Jones and the Spear of Destiny, which moves forward to depict Indiana and his father searching for the Holy Lance in Ireland in 1945.[47] Spielberg intended to have Connery cameo as Henry in Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (2008), but Connery turned it down as he had retired.[48]

References

- Rinzler, J.W.; Laurent Bouzereau (2008). The Complete Making of Indiana Jones. Random House. ISBN 9780091926618. http://shop.indianajones.com/catalog/product.xml?product_id=417814;category_id=408224.

- Joseph McBride (1997). Steven Spielberg: A Biography. New York City: Faber and Faber. ISBN 0-571-19177-0.

- Douglas Brode (1995). The Films of Steven Spielberg. Citadel. ISBN 0-8065-1540-6.

- "Bibliography". TheRaider.net. http://www.theraider.net/films/crusade/making_6_bibliography.php.

- ^ a b c Susan Royal (December 1989). "Always: An Interview with Steven Spielberg". Premiere: pp. 45–56.

- ^ Nancy Griffin (June 1988). "Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade". Premiere.

- ^ a b c d e f (DVD) Indiana Jones: Making the Trilogy. Paramount Pictures. 2003.

- ^ a b c d e f McBride, "An Awfully Big Adventure", p. 379 – 413

- ^ a b c d e "The Hat Trick". TheRaider.net. http://www.theraider.net/films/crusade/making_1_thehattrick.php. Retrieved 2009-02-06.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Rinzler, Bouzereau, "The Monkey King: July 1984 to May 1988", p. 184 - 203.

- ^ McBride, p.318

- ^ David Hughes (November 2005). "The Long Strange Journey of Indiana Jones IV". Empire: p. 131.

- ^ "Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade: An Oral History". Empire. 2008-05-08. http://www.empireonline.com/indy/day17/default.asp. Retrieved 2008-05-08.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "Filming Family Bonds". TheRaider.net. http://www.theraider.net/films/crusade/making_3_production.php. Retrieved 2009-02-06.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Rinzler, Bouzereau, "The Professionals: May 1988 to May 1989", p. 204 - 229.

- ^ a b c d "Crusade: Viewing Guide". Empire: p. 101. October 2006.

- ^ a b Marcus Hearn (2005). The Cinema of George Lucas. New York City: Harry N. Abrams Inc. pp. 159–165. ISBN 0-8109-4968-7.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "A Quest's Completion". TheRaider.net. http://www.theraider.net/films/crusade/making_4_postproduction.php. Retrieved 2009-02-06.

- ^ (2003). The Sound of Indiana Jones (DVD). Paramount Pictures.

- ^ Caryn James (1989-07-09). "It's a New Age For Father–Son Relationships". The New York Times. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=950DEEDE143AF93AA35754C0A96F948260&sec=&spon=&pagewanted=all. Retrieved 2009-02-18.

- ^ "Last Crusade Opening Salvo". Empire: pp. 98–99. October 2006.

- ^ Aljean Harmetz (1989-01-18). "Makers of 'Jones' Sequel Offer Teasers and Tidbits". The New York Times.

- ^ Rob MacGregor (September 1989). Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade. Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-345-36161-5. http://www.randomhouse.com/rhpg/catalog/display.pperl?isbn=9780345361615.

- ^ Staff (1989-06-11). "Paperback Best Sellers: June 11, 1989". The New York Times.

- ^ a b "Apotheosis". TheRaider.net. http://www.theraider.net/films/crusade/making_5_apotheosis.php. Retrieved 2009-02-06.

- ^ Aljean Harmetz (1989-06-14). "Movie Merchandise: The Rush Is On". The New York Times. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=950DE2D71F31F937A25755C0A96F948260&sec=&spon=&pagewanted=all. Retrieved 2009-02-12.

- ^ Edward Douglas (2008-02-17). "Hasbro Previews G.I. Joe, Hulk, Iron Man, Indy & Clone Wars". Superhero Hype!. http://www.superherohype.com/news/topnews.php?id=6807. Retrieved 2008-02-17.

- ^ a b "Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade". Box Office Mojo. http://www.boxofficemojo.com/movies/?id=indianajonesandthelastcrusade.htm. Retrieved 2009-01-06.

- ^ a b "1989 Domestic Grosses". Box Office Mojo. http://www.boxofficemojo.com/yearly/chart/?yr=1989&p=.htm. Retrieved 2009-01-06.

- ^ "1989 Worldwide Grosses". Box Office Mojo. http://www.boxofficemojo.com/yearly/chart/?view2=worldwide&yr=1989&p=.htm. Retrieved 2009-01-06.

- ^ "Indiana Jones". Box Office Mojo. http://www.boxofficemojo.com/franchises/chart/?id=indianajones.htm. Retrieved 2009-01-06.

- ^ Jonathan Rosenbaum. "Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade". Chicago Reader. http://onfilm.chicagoreader.com/movies/capsules/4529_INDIANA_JONES_AND_THE_LAST_CRUSADE. Retrieved 2009-01-07.

- ^ Hal Hinson (1989-05-24). "Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade". The Washington Post. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/style/longterm/movies/videos/indianajonesandthelastcrusadepg13hinson_a0a93b.htm. Retrieved 2009-02-05.

- ^ Desson Thomson (1989-05-26). "Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade". The Washington Post. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/style/longterm/movies/videos/indianajonesandthelastcrusadepg13howe_a0b214.htm. Retrieved 2009-02-05.

- ^ a b Joseph McBride (1989-05-24). "Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade". Variety. http://www.variety.com/review/VE1117791934.html?categoryid=31&cs=1. Retrieved 2009-02-23.

- ^ Vincent Canby (1989-06-18). "Spielberg's Elixir Shows Signs Of Mature Magic". The New York Times. http://movies.nytimes.com/mem/movies/review.html?_r=2&res=950DEFDB1139F93BA25755C0A96F948260&scp=6&sq=Indiana%20Jones%20and%20the%20Last%20Crusade&st=cse. Retrieved 2009-02-05.

- ^ Roger Ebert (1989-05-24). "Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade". Chicago Sun-Times. http://rogerebert.suntimes.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/19890524/REVIEWS/905240301/1023. Retrieved 2008-01-06.

- ^ James Berardinelli. "Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade". ReelViews. http://www.reelviews.net/php_review_template.php?identifier=393. Retrieved 2009-01-07.

- ^ Neil Smith (2002-01-08). "Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade". bbc.co.uk. http://www.bbc.co.uk/films/2002/01/08/indiana_jones_and_the_last_crusade_1989_review.shtml. Retrieved 2009-02-05.

- ^ "Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade". Rotten Tomatoes. http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/indiana_jones_and_the_last_crusade/. Retrieved 2008-01-06.

- ^ "Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade". Metacritic. http://www.metacritic.com/video/titles/indianajoneslastcrusade. Retrieved 2008-01-06.

- ^ "The 62nd Academy Awards (1990) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. http://www.oscars.org/awards/academyawards/legacy/ceremony/62nd-winners.html. Retrieved 2011-10-17.

- ^ Tom O'Neil (2008-05-08). "Will 'Indiana Jones,' Steven Spielberg and Harrison Ford come swashbuckling back into the awards fight?". Los Angeles Times. http://goldderby.latimes.com/awards_goldderby/2008/05/will-indiana-jo.html. Retrieved 2008-05-08.

- ^ "Film Nominations 1989". British Academy of Film and Television Arts. http://www.bafta.org/awards/film/nominations/?year=1989. Retrieved 2009-02-05.

- ^ "1990 Hugo Awards". Thehugoawards.org. http://www.thehugoawards.org/?page_id=30. Retrieved 2009-02-05.

- ^ "Eleventh Annual Youth in Film Awards 1988-1989". Youngartistawards.org. http://www.youngartistawards.org/pastnoms11.htm. Retrieved 2009-02-05.

- ^ "John Williams" (PDF). The Gorfaine/Schwartz Agency, Inc. 2009-02-05. http://www.gsamusic.com/Composers/WLLMS-JN.pdf.

- ^ William McCay (1990). Young Indiana Jones and the Plantation Treasure. Random House. ISBN 0-679-80579-6.

- ^ Les Martin (1993). Young Indiana Jones and the Titanic Adventure. Random House. ISBN 0-679-84925-4.

- ^ Wolfgang Hohlbein (1991). Indiana Jones und das Verschwundene Volk. Goldmann Verlag. ISBN 3-442-41028-2.

- ^ Elaine Lee (w), Dan Spiegle (p). Indiana Jones and the Spear of Destiny 4 (April to July 1995), Dark Horse Comics

- ^ Lucasfilm (2007-06-07). "The Indiana Jones Cast Expands". IndianaJones.com. http://www.indianajones.com/site/index.html?deeplink=news/n13. Retrieved 2009-02-15.

External links

- Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade

- Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade at the Internet Movie Database

- Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade at AllRovi

- Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade at Rotten Tomatoes

- Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade at Box Office Mojo

- Review of Chris Columbus's first draft

Indiana Jones Raiders of the Lost ArkVideo game • Soundtrack Temple of DoomArcade game • Soundtrack Last CrusadeVideo game • Soundtrack Kingdom of the Crystal SkullSoundtrack Television The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles (1992–1996) (episodes)Characters Video games Revenge of the Ancients (1987) · Fate of Atlantis (1992) · Young Indiana Jones Chronicles (1992) · The Pinball Adventure (1993) · Greatest Adventures (1994) · Desktop Adventures (1996) · Infernal Machine (1999) · Emperor's Tomb (2003) · Lego Indiana Jones: The Original Adventures (2008) · Staff of Kings (2009) · Lego Indiana Jones 2: The Adventure Continues (2009)Attractions Temple of the Forbidden Eye · Temple of the Crystal Skull · Temple du Péril · Epic Stunt Spectacular!Literature Other media Role-playing game · Comics · Nuking the fridge · Lego Indiana Jones · Lego Indiana Jones and the Raiders of the Lost Brick · Indiana Jones Summer of Hidden Mysteries Category:Indiana Jones

Category:Indiana JonesSteven Spielberg filmography 1970s Duel (1971) · The Sugarland Express (1974) · Jaws (1975) · Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977) · 1941 (1979)1980s Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981) · E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (1982) · Twilight Zone: The Movie (1983; one segment) · Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (1984) · The Color Purple (1985) · Empire of the Sun (1987) · Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989) · Always (1989)1990s Hook (1991) · Jurassic Park (1993) · Schindler's List (1993) · The Lost World: Jurassic Park (1997) · Amistad (1997) · Saving Private Ryan (1998)2000s A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001) · Minority Report (2002) · Catch Me If You Can (2002) · The Terminal (2004) · War of the Worlds (2005) · Munich (2005) · Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (2008)2010s The Adventures of Tintin (2011) · War Horse (2011) · Lincoln (2012)Production

creditsI Wanna Hold Your Hand (1978) · Used Cars (1980) · Continental Divide (1981) · Poltergeist (1982) · E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (1982) · Twilight Zone: The Movie (1983) · Gremlins (1984) · Back to the Future (1985) · The Goonies (1985) · Young Sherlock Holmes (1985) · The Color Purple (1985) · An American Tail (1986) · The Money Pit (1986) · *batteries not included (1987) · Harry and the Hendersons (1987; uncredited) · Innerspace (1987) · Empire of the Sun (1987) · Three O'Clock High (1987; uncredited) · The Land Before Time (1988) · Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988) · Back to the Future Part II (1989) · Always (1989) · Dad (1989) · Arachnophobia (1990) · Back to the Future Part III (1990) · Gremlins 2: The New Batch (1990) · Joe Versus the Volcano (1990) · An American Tail: Fievel Goes West (1991) · Cape Fear (1991) · We're Back! A Dinosaur's Story (1993) · Schindler's List (1993) · The Flintstones (1994) · The Little Rascals (1994; uncredited) · Casper (1995) · Balto (1995) · Twister (1996) · Men in Black (1997) · Amistad (1997) · Deep Impact (1998) · The Mask of Zorro (1998) · Saving Private Ryan (1998) · The Last Days (1998) · The Prince of Egypt (1998; uncredited) · The Haunting (1999; uncredited) · Wakko's Wish (1999) · The Flintstones in Viva Rock Vegas (2000) · Evolution (2001; uncredited) · A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001) · Jurassic Park III (2001) · Men in Black II (2002) · Catch Me If You Can (2002) · The Terminal (2004) · The Legend of Zorro (2005) · Memoirs of a Geisha (2005) · Munich (2005) · Monster House (2006) · Flags of Our Fathers (2006) · Letters from Iwo Jima (2006) · Disturbia (2007; uncredited) · Transformers (2007) · Eagle Eye (2008) · Transformers: Revenge of the Fallen (2009) · The Lovely Bones (2009) · Hereafter (2010) · True Grit (2010) · Super 8 (2011) · Transformers: Dark of the Moon (2011) · Cowboys & Aliens (2011) · Real Steel (2011) · The Adventures of Tintin: Secret of the Unicorn (2011) · War Horse (2011) · Men in Black III (2012) · Cloud Atlas (2012)Television Night Gallery (1970) · Columbo (1971) · Amazing Stories (1985–1987) · Tiny Toon Adventures (1990–1992) · A Wish for Wings That Work (1991; uncredited) · Tiny Toon Adventures: How I Spent My Vacation (1992) · Family Dog (1993) · seaQuest DSV (1993–1995) · Animaniacs (1993–1998) · ER (1994) · Pinky and the Brain / Pinky, Elmyra & the Brain (1995–1999) · Freakazoid! (1995–1997) · High Incident (1996–1997) · Toonsylvania (1998) · Invasion America (1998) · Band of Brothers (2001) · Taken (2002) · Into the West (2005) · On the Lot (2007) · United States of Tara (2009–2011) · The Pacific (2010) · Falling Skies (2011–present) · Terra Nova (2011–present) · The River (2012–present) · Smash (2012–present)Games The Dig (1995) · Medal of Honor (1999) · Medal of Honor: Underground (2000) · Boom Blox (2008) · Boom Blox Bash Party (2009)Short films Tummy Trouble (1989; played with Honey, I Shrunk the Kids) · Roller Coaster Rabbit (1990; played with Dick Tracy) · Trail Mix-Up (1993; played with A Far Off Place) · I'm Mad (1994; played with Thumbelina)See also Firelight (1964) · Amblin' (1968) · Something Evil (1972) · "Kick the Can" (Twilight Zone: The Movie segment) (1983) · Bee Movie (2007)

Filmography · Amblin Entertainment · DreamWorks · USC Shoah Foundation Institute for Visual History and Education · AmblimationGeorge Lucas filmography Films directed THX 1138 (1971) · American Graffiti (1973) · Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope (1977) · Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace (1999) · Star Wars Episode II: Attack of the Clones (2002) · Star Wars Episode III: Revenge of the Sith (2005)Produced 1970sMore American Graffiti (1979)1980sKagemusha (1980) · Star Wars Episode V: The Empire Strikes Back (1980) · Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981) · Body Heat (1981; uncredited) · Star Wars Episode VI: Return of the Jedi (1983) · Twice Upon a Time (1983) · Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (1984) · Latino (1985; uncredited) · Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters (1985) · Howard the Duck (1986) · Labyrinth (1986) · Captain EO (1986) · Star Tours (1987) · The Land Before Time (1988) · Tucker: The Man and His Dream (1988) · Powaqqatsi (1988) · Willow (1988) · Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989)1990s2000sStar Wars: Clone Wars (TV series) (2003) · Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (2008) · Star Wars: The Clone Wars (2008) · Star Wars: The Clone Wars (TV series) (2008)2010sShorts Freiheit (1965) · Look at Life (1965) · Herbie (1966) · 1:42.08: A Man and His Car (1966) · The Emperor (1967) · Electronic Labyrinth: THX 1138 4EB (1967) · Anyone Lived in a Pretty How Town (1967) · 6-18-67 (1967) · Filmmaker (1968)Related Star Wars Episode V: The Empire Strikes Back (1981) · Raiders of the Lost Ark (1982) · Blade Runner (1983) · Star Wars Episode VI: Return of the Jedi (1984) · 2010 (1985) · Back to the Future (1986) · Aliens (1987) · The Princess Bride (1988) · Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1989) · Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1990) · Edward Scissorhands (1991) · Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1992) · "The Inner Light" (Star Trek: The Next Generation) (1993) · Jurassic Park (1994) · "All Good Things..." (Star Trek: The Next Generation) (1995) · Babylon 5: "The Coming of Shadows" (1996) · Babylon 5: "Severed Dreams" (1997) · Contact (1998) The Truman Show (1999) Galaxy Quest (2000) Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2001) The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring (2002)

Complete List · (1958–1980) · (1981–2002) · (Long form: 2003–2020) · (Short form: 2003–2020) Categories:- 1989 films

- American films

- English-language films

- 1980s action films

- 1980s adventure films

- Films set in 1912

- Films set in 1938

- American action films

- American adventure films

- Media inspired by the legend of the Holy Grail

- Hugo Award Winners for Best Dramatic Presentation

- Lucasfilm films

- Paramount Pictures films

- Sequel films

- Films set in Austria

- Films set in Berlin

- Films set in Turkey

- Films set in Venice

- Films set in Utah

- Films shot in Jordan

- Films shot in Turkey

- Films shot in Utah

- Films shot anamorphically

- Films shot in Deluxe Color

- Nazi Germany in fiction

- Films with Nazi occultism

- Adolf Hitler in fiction

- Films directed by Steven Spielberg

- Treasure hunt films

- Rail transport films

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.