- Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom

-

This article is about the film. For the soundtrack, see Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (soundtrack). For the arcade game, see Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (arcade game).

Indiana Jones and

the Temple of Doom

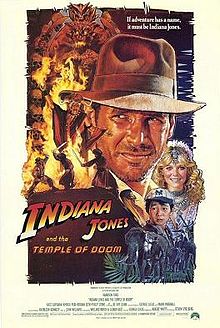

Theatrical poster by Drew StruzanDirected by Steven Spielberg Produced by George Lucas

Robert Watts

Frank Marshall

Kathleen KennedyScreenplay by Willard Huyck

Gloria KatzStory by George Lucas Starring Harrison Ford

Kate Capshaw

Jonathan Ke Quan

Amrish Puri

Roshan Seth

Philip StoneMusic by John Williams Cinematography Douglas Slocombe Editing by Michael Kahn Studio Lucasfilm Distributed by Paramount Pictures Release date(s) May 23, 1984 Running time 118 minutes Country United States Language English Budget $28.17 million[1] Box office $333,107,271 Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom is a 1984 American adventure film directed by Steven Spielberg. It is the second (chronologically the first) film in the Indiana Jones franchise and prequel to Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981). After arriving in India, Indiana Jones is asked by a desperate village to find a mystical stone. He agrees, stumbling upon a Kali Thuggee religious cult practicing child slavery, black magic and ritual human sacrifice.

Producer and co-writer George Lucas decided to make the film a prequel as he did not want the Nazis to be the villains again. The original idea was to set the film in China, with a hidden valley inhabited by dinosaurs. Other rejected plot devices included the Monkey King and a haunted castle in Scotland. Lucas then wrote a film treatment that resembled the final storyline of the film. Lawrence Kasdan, Lucas's collaborator on Raiders of the Lost Ark, turned down the offer to write the script, and Willard Huyck and Gloria Katz were hired as his replacement.

The film was released to financial success but mixed reviews, which criticized the on-screen violence, later contributing to the creation of the PG-13 rating. However, critical opinion has improved since 1984, citing the film's intensity and imagination. Some of the film's cast and crew, including Spielberg, retrospectively view the film in an unfavorable light. The film has also been the subject of controversy due to its portrayal of India and Hinduism.

Contents

Plot

In 1935, Indiana Jones narrowly escapes the clutches of Lao Che, a crime boss in Shanghai. With his eleven-year old Chinese sidekick Short Round and the gold-digging nightclub singer Willie Scott in tow, Indiana flees Shanghai on a plane that, unknown to them, is owned by Lao. The pilots leave the plane to crash over the Himalayas, though the trio narrowly manage to escape on an inflatable boat and ride down the slopes into a raging river. They come to Mayapore, a desolate village in northern India, where the poor villagers believe them to have been sent by the Hindu god Shiva and enlist their help to retrieve the sacred Sivalinga stone stolen from their shrine, as well as the community's children, from evil forces in the nearby Pankot Palace. During the journey to Pankot, Indiana hypothesizes that the stone may be one of the five fabled Sankara stones which promise fortune and glory.

The trio receive a warm welcome from the residents of Pankot Palace, who rebuff Indiana's questions about the villagers' claims and his theory that the ancient Thuggee cult is responsible for their troubles. Later that night, however, Indiana is attacked by an assassin, leading Indy, Willie, and Short Round to believe that something is amiss. From the tunnels of the palace, they travel through an underground temple where the Thuggee worship the Hindu goddess Kali with human sacrifice. The trio discover that the Thuggee, led by their evil, villainous high priest Mola Ram, are in possession of three of the five Sankara stones, and have enslaved the children to mine for the final two stones, which they hope will allow them to rule the world. As Indiana tries to retrieve the stones, he, Willie and Short Round are captured and separated. Indiana is forced to drink a potion called the "Blood of Kali", which places him in a trance-like state called the "Black Sleep of Kali Ma". As a result, he begins to mindlessly serve Mola Ram. Willie, meanwhile, is kept as a human sacrifice, while Short Round is put in the mines to labour alongside the enslaved children. Short Round breaks free and escapes back into the temple where he burns Indiana with a torch, shocking him out of the trance. While Mola Ram escapes, Indiana and Short Round rescue Willie, retrieve the three Sankara stones and free the village children.

After a mine cart chase to escape the temple, the trio emerge above ground and are again cornered by Mola Ram and his henchmen on a rope bridge on both ends over a gorge with crocodile-infested river flowing within. Using a sword stolen from one of the Thuggee warriors, Indiana cuts the rope bridge in half, leaving everyone to hang on for their lives. In one final struggle against Mola Ram for the Sankara stones, Indiana invokes an incantation to Shiva, causing the stones to glow red hot. Two of the stones fall into the river, while the last falls into and burns Mola Ram's hand. Indiana catches the now-cool stone, while Mola Ram falls into the river below, where he is eaten by crocodiles. The Thuggee across then attempt to shoot Indiana with arrows, until a company of British Indian Army riflemen from Pankot arrive, having been summoned by the palace maharajah. In the ensuing firefight, over half of the Thuggee archers are killed and the remainder are surrounded and captured. Indiana, Willie and Short Round return victoriously to the village with the missing Sivalinga stone and the children.

Cast

- Harrison Ford as Indiana Jones: An archaeologist adventurer who is asked by a desperate Indian village to retrieve a mysterious stone. Ford undertook a strict physical exercise regimen headed by Jake Steinfeld to gain more muscular tone for the part.[2]

- Kate Capshaw as Wilhelmina "Willie" Scott: An American nightclub singer working in Shanghai. Willie is unprepared for her adventure with Indy and Short Round, and appears to be a damsel in distress. She also forms a romantic relationship with Indy. Over 120 actresses auditioned for the role, including Sharon Stone.[1][3] To prepare for the role, Capshaw watched The African Queen and A Guy Named Joe. Spielberg wanted Willie to be a complete contrast to Marion Ravenwood from Raiders of the Lost Ark, so Capshaw dyed her brown hair blonde for the part. Costume designer Anthony Powell wanted the character to have red hair.[4]

- Jonathan Ke Quan as Short Round: Indiana's eleven-year old Chinese sidekick, who drives the 1936 Auburn Boat Tail Speedster which allows Indiana to escape during the opening sequence. Quan was chosen as part of a casting call in Los Angeles, California.[4] Around 6000 actors auditioned worldwide for the part: Quan was cast after his brother auditioned for the role. Spielberg liked his personality, so he and Ford improvised the scene where Short Round accuses Indiana of cheating during a card game.[3] He was credited by his birthname, Ke Huy Quan.

- Amrish Puri as Mola Ram: A demonic Thuggee priest who performs rituals of human sacrifices. The character is named after a 17th century Indian painter. Lucas wanted Mola Ram to be terrifying, so the screenwriters added elements of Aztec and Hawaiian human sacrificers, and European devil worship to the character.[5] To create his headdress, make-up artist Tom Smith based the skull on a cow, and used a latex shrunken head.[6]

- Roshan Seth as Chattar Lal: The Prime Minister of the Maharaja of Pankot. Chattar, also a Thuggee worshiper, is enchanted by Indy, Willie and Short Round's arrival, but is offended by Indy's questioning of the palace's history and the archaeologist's own dubious past.

- Philip Stone as Captain Philip Blumburtt: A British Captain in the Indian Army called to Pankot Palace for "exercises". Alongside a unit of his riflemen, Blumburtt assists Indiana towards the end in fighting off Thuggee reinforcements. David Niven was attached to the role but died before filming began.

- Raj Singh as Zalim Singh: The adolescent Maharajá of Pankot, who appears as an innocent puppet of the Thuggee faithful. In the end he helps to defeat them.

- D. R. Nanayakkara as Shaman: The leader of a small village that recruits Indiana to retrieve their stolen sacred Shiva lingam stone

- Roy Chiao as Lao Che: A Shanghai crime boss who hires Indy to recover the cremated ashes of one of his ancestors, only to attempt to cheat him out of his fee, a large diamond.

- David Yip as Wu Han: A friend of Indiana. He is killed by one of Lao Che's sons while posing as a waiter at the Club Obi Wan.

Actor Pat Roach plays the overseer in the mines. Steven Spielberg, George Lucas, Frank Marshall, Kathleen Kennedy, and Dan Aykroyd have cameos at the airport.[2]

Production

Development

When George Lucas first approached Steven Spielberg for Raiders of the Lost Ark, Spielberg recalled, "George said if I directed the first one then I would have to direct a trilogy. He had three stories in mind. It turned out George did not have three stories in mind and we had to make up subsequent stories."[7] Spielberg and Lucas attributed the film's tone, which was darker than Raiders of the Lost Ark, to their personal moods following the breakups of their relationships (Spielberg with Amy Irving, Lucas with Marcia).[8] In addition Lucas felt "it had to have been a dark film. The way Empire Strikes Back was the dark second act of the Star Wars trilogy."[4]

Lucas made the film a prequel as he did not want the Nazis to be the villains once more.[8] Spielberg originally wanted to bring Marion Ravenwood back,[7] with Abner Ravenwood being considered as a possible character.[4] Lucas created an opening chase scene that had Indiana Jones on a motorcycle on the Great Wall of China. In addition Indiana discovered a "Lost World pastiche with a hidden valley inhabited by dinosaurs". Chinese authorities refused to allow filming,[2] and Lucas considered the Monkey King as the plot device.[8] Lucas wrote a film treatment that included a haunted castle in Scotland, but Spielberg felt it was too similar to Poltergeist. The haunted castle in Scotland slowly transformed into a demonic temple in India.[4]

Lucas came up with ideas that involved a religious cult devoted to child slavery, black magic and ritual human sacrifice. Lawrence Kasdan of Raiders of the Lost Ark was asked to write the script. "I didn't want to be associated with Temple of Doom," he reflected. "I just thought it was horrible. It's so mean. There's nothing pleasant about it. I think Temple of Doom represents a chaotic period in both their [Lucas and Spielberg] lives, and the movie is very ugly and mean-spirited."[2] Lucas hired Willard Huyck and Gloria Katz to write the script because of their knowledge of Indian culture.[7] Gunga Din served as an influence for the film.[4]

Huyck and Katz spent four days at Skywalker Ranch for story discussions with Lucas and Spielberg in early-1982.[4] Lucas's initial idea for Indiana's sidekick was a virginal young princess, but Huyck, Katz and Spielberg disliked the idea.[5] Just as Indiana Jones was named after Lucas's Alaskan Malamute, Willie was named after Spielberg's Cocker Spaniel, and Short Round was named after Huyck's dog, whose name was derived from The Steel Helmet.[4] Lucas handed Huyck and Katz a 20-page treatment in May 1982 titled Indiana Jones and the Temple of Death to adapt into a screenplay.[4] Scenes such as the fight scene in Shanghai, escape from the airplane and the mine cart chase came from original scripts of Raiders of the Lost Ark.[9]

Lucas, Huyck and Katz had been developing Radioland Murders (1994) since the early 1970s. The opening music number was taken from that script and applied to Temple of Doom.[9] Spielberg reflected, "George's idea was to start the movie with a musical number. He wanted to do a Busby Berkeley dance number. At all our story meetings he would say, 'Hey, Steven, you always said you wanted to shoot musicals.' I thought, 'Yeah, that could be fun.'"[4] The first draft was delivered in early-August 1982 with a second draft in September. Captain Blumburtt, Chattar Lal and the boy Maharaja originally had more crucial roles. A dogfight was deleted, while those who drank the Kali blood turned into zombies with physical superhuman abilities. During pre-production the Temple of Death title was replaced with Temple of Doom. From March—April 1983 Huyck and Katz simultaneously performed rewrites for a final shooting script.[4]

Filming

The filmmakers were denied permission to film in North India and Amber Fort due to the government finding the script racist and offensive.[2][7][9] The government demanded many script changes, rewritings and final cut privilege.[4] As a result, location work went to Kandy, Sri Lanka, with matte paintings and scale models applied for the village, temple, and Pankot Palace. Budgetary inflation also caused Temple of Doom to cost $28.17 million, $8 million more than Raiders of the Lost Ark.[9] Filming began on 18 April 1983 in Kandy,[10] and moved to Elstree Studios in Hertfordshire, England on May 5. Producer Frank Marshall recalled, "when filming the bug scenes, crew members would go home and find bugs in their hair, clothes and shoes."[10] Eight out of the nine sound stages at Elstree housed the filming of Temple of Doom. Lucas biographer Marcus Hearn observed, "Douglas Slocombe's skillful lighting helped disguise the fact that about 80 percent of the film was shot with sound stages."[11]

Danny Daniels choreographed the opening music number "Anything Goes". Capshaw learned to sing in Mandarin and took tap dance lessons. However, when wearing her dress, which was too tight, Capshaw was not able to tap dance. One of her red dresses was eaten by an elephant during filming; a second was made by costume designer Anthony Powell.[7] Production designer Norman Reynolds could not return for Temple of Doom because of his commitment to Return of the Jedi. Elliot Scott (Labyrinth, Who Framed Roger Rabbit), Reynolds' mentor, was hired. To build the rope bridge the filmmakers found a group of British engineers working on the nearby Balfour Beatty dam.[4] Harrison Ford suffered a severe spinal disc herniation while riding elephants. A hospital bed was brought on set for Ford to rest between takes. Lucas stated, "He could barely stand up, yet he was there every day so shooting would not stop. He was in incomprehensible pain, but he was still trying to make it happen."[2] With no alternatives, Lucas shut down production while Ford was flown to Centinela Hospital on June 21 for recovery.[10] Stunt double Vic Armstrong spent five weeks as a stand-in for various shots. Wendy Leach, Armstrong's wife, served as Capshaw's stunt double.[12]

Macau was substituted for Shanghai,[9] while cinematographer Douglas Slocombe caught fever from June 24 to July 7 and could not work. Ford returned on August 8. Despite the problems during filming, Spielberg was able to complete Temple of Doom on schedule and on budget, finishing on principal photography on August 26.[10] Various pick-ups took place afterwards. This included Snake River Canyon in Idaho, Mammoth Mountain, Tuolumne and American River, Yosemite National Park, San Joaquin Valley, Hamilton Air Force Base and Arizona.[1] Producer Frank Marshall directed a second unit in Florida in January 1984, using alligators to double as crocodiles.[1][8] The mine chase was a combination of a roller coaster and scale models with dolls doubling for the actors.[9] Minor stop motion was also used for the sequence. Visual effects supervisors Dennis Muren, Joe Johnston and a crew at Industrial Light & Magic provided the visual effects work,[13] while Skywalker Sound, headed by Ben Burtt, commissioned the sound design. Burtt recorded roller coasters at Disneyland Park in Anaheim for the mine cart scene.[14]

Release

"After I showed the film to George [Lucas], at an hour and 55 minutes, we looked at each other," Spielberg remembered. "The first thing that we said was, 'Too fast'. We needed to decelerate the action. I did a few more matte shots to slow it down. We made it a little bit slower, by putting breathing room back in so there'd be a two-hour oxygen supply for the audience."[1] Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom was released on 23 May 1984 in America, accumulating a record-breaking $US45.7 million in its first week.[11] The film went on to gross $333.11 million worldwide, with $180 million in North America and the equivalent of $153.11 million in other markets.[15] Temple of Doom had the highest opening weekend of 1984, and was the third highest grossing film in North America of that year, behind Beverly Hills Cop and Ghostbusters.[16] It was also the tenth highest grossing film of all time during its release.[15]

LucasArts and Atari Games promoted the film by releasing an arcade game. Hasbro released a toy line based on the film in September 2008.[17]

Reception

The film received mixed reviews upon its release,[2] but has continued to receive critical praise over the years. American Movie Classics considers Temple of Doom to be one of the best films of 1984.[18] Based on 59 reviews collected by Rotten Tomatoes, 85% wrote positive reviews of the film, with an average score of 7.2/10.[19] Roger Ebert called Temple of Doom "the most cheerfully exciting, bizarre, goofy, romantic adventure movie since Raiders, and it is high praise to say that it's not so much a sequel as an equal. It's quite an experience."[20] Vincent Canby felt the film was "too shapeless to be the fun that Raiders is, but shape may be beside the point. Old-time, 15-part movie serials didn't have shape. They just went on and on and on, which is what Temple of Doom does with humor and technical invention."[21] Colin Covert of the Star Tribune called the film "sillier, darkly violent and a bit dumbed down, but still great fun."[22]

Dave Kehr gave a largely negative review; "The film betrays no human impulse higher than that of a ten-year-old boy trying to gross out his baby sister by dangling a dead worm in her face."[23] Ralph Novak of People complained "The ads that say 'this film may be too intense for younger children' are fraudulent. No parent should allow a young child to see this traumatizing movie; it would be a cinematic form of child abuse. Even Harrison Ford is required to slap Quan and abuse Capshaw. There are no heroes connected with the film, only two villains; their names are Steven Spielberg and George Lucas."[9]

Kate Capshaw called her character "not much more than a dumb screaming blonde."[9] Capshaw, who is a feminist, was annoyed by the criticism she received of her portrayal.[7] Steven Spielberg said in 1989, "I wasn't happy with Temple of Doom at all. It was too dark, too subterranean, and much too horrific. I thought it out-poltered Poltergeist. There's not an ounce of my own personal feeling in Temple of Doom." He later added during the "Making of Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom" documentary, "Temple of Doom is my least favorite of the trilogy. I look back and I say, 'Well the greatest thing that I got out of that was I met Kate Capshaw. We married years later and that to me was the reason I was fated to make Temple of Doom."[1]

The film's depiction of Hindus caused controversy in India, and brought it to the attention of the country's censors, who placed a temporary ban on it.[24] The inaccurate depiction of Goddess Kali as a representative of the underworld and evil met with much criticism as she is instead the Goddess of Energy (Shakti). However, it is true that the thuggee cult, who were actually robbers and nothing more, used to worship Kali and offer human sacrifices so that their venture may succeed. Nevertheless, it was nothing as compared to its depiction in Spielberg's film. The depiction of Indian cuisine was also condemned as it has no relation whatsoever with "baby snakes, eyeball soup, beetles and chilled monkey brains." Shashi Tharoor has condemned the film and pointed to numerous offensive and factually inaccurate portrayals.[25] Yvette Rosser has criticized the film for contributing to racist stereotypes of Indians in western society, writing "[it] seems to have been taken as a valid portrayal of India by many teachers, since a large number of students surveyed complained that teachers referred to the eating of monkey brains."[26]

Impact

Dennis Muren and the visual effects department at Industrial Light & Magic won the Academy Award for Visual Effects at the 57th Academy Awards. John Williams was nominated for "Original Music Score".[27] The visual effects crew won the same category at the 38th British Academy Film Awards. Cinematographer Douglas Slocombe, editor Michael Kahn, Ben Burtt and other sound designers at Skywalker Sound received nominations.[28] Spielberg, the writers, Harrison Ford, Jonathan Ke Quan, Anthony Powell and makeup designer Tom Smith were nominated for their work at the Saturn Awards. Temple of Doom was nominated for Best Fantasy Film but lost to Ghostbusters.[29]

Temple of Doom was originally released with a PG rating, but it created a huge controversy at the time. Steven Spielberg would later lobby Jack Valenti and the Motion Picture Association of America to create the PG-13 rating to fulfill the need for a film rating between PG and R.[30] Another film that influenced the PG-13 rating was the equally dark and violent family film Gremlins.

References

- ^ a b c d e f Rinzler, Bouzereau, Chapter 8: "Forward on All Fronts (August 1983—June 1984)", p. 168—183

- ^ a b c d e f g John Baxter (1999). "Snake Surprise". Mythmaker: The Life and Work of George Lucas. Avon Books. pp. 332–341. ISBN 0380978334.

- ^ a b "The People Who Were Almost Cast". Empire. http://www.empireonline.com/indy/day1/2.asp. Retrieved 2008-08-26.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m J.W. Rinzler; Laurent Bouzereau (2008). "Temple of Death: (June 1981—April 1983)". The Complete Making of Indiana Jones. Random House. pp. 129–141. ISBN 9780091926618.

- ^ a b "Adventure's New Name". TheRaider.net. http://www.theraider.net/films/todoom/making_1_newideas.php. Retrieved 2008-04-23.

- ^ "Scouting for Locations and New Faces". TheRaider.net. http://www.theraider.net/films/todoom/making_2_newfaces.php. Retrieved 2008-04-23.

- ^ a b c d e f Indiana Jones: Making the Trilogy, 2003, Paramount Pictures

- ^ a b c d "Temple of Doom: An Oral History". Empire. 2008-05-01. http://www.empireonline.com/indy/day10/. Retrieved 2008-05-01.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Joseph McBride (1997). "Ecstasy and Grief". Steven Spielberg: A Biography. New York City: Faber and Faber. pp. 323–358. ISBN 0-571-19177-0.

- ^ a b c d Rinzler, Bouzereau, Chapter 6: "Doomruners (April—August 1983, p. 142—167

- ^ a b Marcus Hearn (2005). The Cinema of George Lucas. Harry N. Abrams Inc. pp. 144–147. ISBN 0-8109-4968-7, 0-8109-4968-7 0-8109-4968-7, 0-8109-4968-7.

- ^ The Stunts of Indiana Jones, 2003, Paramount Pictures

- ^ The Light and Magic of Indiana Jones, 2003, Paramount Pictures

- ^ The Sound of Indiana Jones, 2003, Paramount Pictures

- ^ a b "Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom". Box Office Mojo. http://www.boxofficemojo.com/movies/?id=indianajonesandthetempleofdoom.htm. Retrieved 2008-08-24.

- ^ "1984 Domestic Grosses". Box Office Mojo. http://www.boxofficemojo.com/yearly/chart/?yr=1984&p=.htm. Retrieved 2008-08-24.

- ^ Edward Douglas (2008-02-17). "Hasbro Previews G.I. Joe, Hulk, Iron Man, Indy & Clone Wars". Superhero Hype!. http://www.superherohype.com/news/topnews.php?id=6807. Retrieved 2008-02-17.

- ^ "The Greatest Films of 1984". AMC Filmsite.org. http://www.filmsite.org/1984.html. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

- ^ "Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom". Rotten Tomatoes. http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/indiana_jones_and_the_temple_of_doom/. Retrieved 2008-08-24.

- ^ "Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom". Chicago Sun-Times. http://rogerebert.suntimes.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/19840101/REVIEWS/401010348/1023. Retrieved 2008-08-24.

- ^ Vincent Canby (2008-05-21). "Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom". The New York Times.

- ^ Colin Covert (2008-05-21). "Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom". Star Tribune.

- ^ Dave Kehr (2008-05-21). "Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom". Chicago Reader.

- ^ Gogoi, Pallavi (2006-11-05). "Banned Films Around the World: Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom". BusinessWeek. http://images.businessweek.com/ss/06/11/1106_banned/source/7.htm.

- ^ Tharoor, Shashi. "SHASHI ON SUNDAY: India, Jones and the template of dhoom". The Times Of India. http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/home/sunday-toi/all-that-matters/SHASHI-ON-SUNDAY-India-Jones-and-the-template-of-dhoom/articleshow/1746623.cms?flstry=1.

- ^ Yvette Rosser. "Teaching South Asia". Missouri Southern State University. Archived from the original on 2005-01-08. http://web.archive.org/web/20050108064134/http://www.mssu.edu/projectsouthasia/tsa/VIN1/Rosser.htm. Retrieved 2008-08-27.

- ^ "Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. http://awardsdatabase.oscars.org/ampas_awards/DisplayMain.jsp?curTime=1219724364138. Retrieved 2008-08-25.

- ^ "Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom". British Academy of Film and Television Arts. http://www.bafta.org/awards-database.html?sq=Indiana+Jones+and+the+Temple+of+Doom. Retrieved 2008-08-25.

- ^ "Past Saturn Awards". Saturn Awards. http://www.saturnawards.org/past.html. Retrieved 2008-08-25.

- ^ Anthony Breznican (2004-08-24). "PG-13 remade Hollywood ratings system". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. http://www.seattlepi.com/movies/187529_pg13rating24.html. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

Further reading

- Willard Huyck; Gloria Katz (October 1984). Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom: The Illustrated Screenplay. Ballantine Books. ISBN 0345318781.

- James Kahn (May 1984). Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom. novelization of the film. Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-345-31457-4.

- Rinzler, J. W.; Bouzereau, Laurent (January 1, 2008). The Complete Making of Indiana Jones. Ebury Publishing. ISBN 978-0091926618.

- Suzanne Weyn (May 2008). Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom. "junior novelization" of the film. Scholastic Corporation. ISBN 0545042550.

External links

- Official website

- Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom at AllRovi

- Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom at the Internet Movie Database

- Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom at Rotten Tomatoes

- Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom at Box Office Mojo

Indiana Jones Raiders of the Lost ArkVideo game • Soundtrack Temple of DoomArcade game • Soundtrack Last CrusadeVideo game • Soundtrack Kingdom of the Crystal SkullSoundtrack Television The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles (1992–1996) (episodes)Characters Video games Revenge of the Ancients (1987) · Fate of Atlantis (1992) · Young Indiana Jones Chronicles (1992) · The Pinball Adventure (1993) · Greatest Adventures (1994) · Desktop Adventures (1996) · Infernal Machine (1999) · Emperor's Tomb (2003) · Lego Indiana Jones: The Original Adventures (2008) · Staff of Kings (2009) · Lego Indiana Jones 2: The Adventure Continues (2009)Attractions Temple of the Forbidden Eye · Temple of the Crystal Skull · Temple du Péril · Epic Stunt Spectacular!Literature Other media Role-playing game · Comics · Nuking the fridge · Lego Indiana Jones · Lego Indiana Jones and the Raiders of the Lost Brick · Indiana Jones Summer of Hidden MysteriesGeorge Lucas filmography Films directed THX 1138 (1971) · American Graffiti (1973) · Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope (1977) · Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace (1999) · Star Wars Episode II: Attack of the Clones (2002) · Star Wars Episode III: Revenge of the Sith (2005)Produced 1970sMore American Graffiti (1979)1980sKagemusha (1980) · Star Wars Episode V: The Empire Strikes Back (1980) · Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981) · Body Heat (1981; uncredited) · Star Wars Episode VI: Return of the Jedi (1983) · Twice Upon a Time (1983) · Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (1984) · Latino (1985; uncredited) · Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters (1985) · Howard the Duck (1986) · Labyrinth (1986) · Captain EO (1986) · Star Tours (1987) · The Land Before Time (1988) · Tucker: The Man and His Dream (1988) · Powaqqatsi (1988) · Willow (1988) · Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989)1990s2000sStar Wars: Clone Wars (TV series) (2003) · Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (2008) · Star Wars: The Clone Wars (2008) · Star Wars: The Clone Wars (TV series) (2008)2010sShorts Freiheit (1965) · Look at Life (1965) · Herbie (1966) · 1:42.08: A Man and His Car (1966) · The Emperor (1967) · Electronic Labyrinth: THX 1138 4EB (1967) · Anyone Lived in a Pretty How Town (1967) · 6-18-67 (1967) · Filmmaker (1968)Related Categories:- 1984 films

- American films

- English-language films

- American adventure films

- 1980s action films

- 1980s adventure films

- Films directed by Steven Spielberg

- Films set in 1935

- Films set in India

- Films set in Shanghai

- Films shot in Deluxe Color

- Films shot anamorphically

- Films shot in China

- Films shot in Sri Lanka

- Films shot in Arizona

- Films shot in Florida

- Films shot in California

- Films shot in Washington (state)

- Films that won the Best Visual Effects Academy Award

- Lucasfilm films

- Paramount Pictures films

- Prequel films

- Treasure hunt films

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.