- Mercury in fish

-

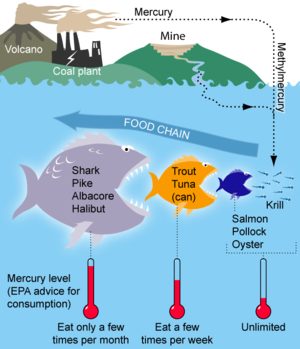

Fish and shellfish concentrate mercury in their bodies, often in the form of methylmercury, a highly toxic organic compound of mercury. Fish products have been shown to contain varying amounts of heavy metals, particularly mercury and fat-soluble pollutants from water pollution. Species of fish that are long-lived and high on the food chain, such as marlin, tuna, shark, swordfish, king mackerel, tilefish, northern pike, and lake trout contain higher concentrations of mercury than others.[1]

The presence of mercury in fish can be a health issue, particularly for women who are or may become pregnant, nursing mothers, and young children.

Contents

Biomagnification

Main article: BiomagnificationMercury and methylmercury is present in only small concentrations in seawater. However, it is absorbed, usually as methylmercury, by algae at the start of the food chain. This algae is then eaten by fish and other organisms higher in the food chain. Fish efficiently absorb methylmercury, but only very slowly excrete it.[2] Methylmercury is not soluble and therefore is not apt to be excreted. Instead, it accumulates, primarily in the viscera although also in the muscle tissue.[3] This results in the bioaccumulation of mercury, in a buildup in the adipose tissue of successive trophic levels: zooplankton, small nekton, larger fish etc. Anything which eats these fish within the food chain also consumes the higher level of mercury the fish have accumulated. This process explains why predatory fish such as swordfish and sharks or birds like osprey and eagles have higher concentrations of mercury in their tissue than could be accounted for by direct exposure alone. Species on the food chain can amass body concentrations of mercury up to ten times higher than the species they consume. This process is called biomagnification. For example, herring contains mercury levels at about 0.01 ppm while shark contains mercury levels greater than 1 ppm.[4]

Range of contamination

U.S. government scientists tested fish in 291 streams around the country for mercury contamination. They found mercury in every fish tested, according to the study by the U.S. Department of the Interior. They found mercury even in fish of isolated rural waterways. Twenty five percent of the fish tested had mercury levels above the safety levels determined by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency for people who eat the fish regularly.[5]

The table in[6] provides a list of fishes and shellfishes and their mercury content.

Sources

See also: Mercury cycleMuch of the mercury that eventually finds its way into fish originates with coal-burning power plants and chlorine production plants.[7] The largest source of mercury contamination in the United States is coal-fueled power plant emissions.[5] Chlorine chemical plants use mercury to extract chlorine from salt, which in many parts of the world is discharged as mercury compounds in waste water, though this process has been replaced for the most part by the more economically viable membrane cell process, which does not use mercury. Coal contains mercury as a natural contaminant. When it is fired for electricity generation, the mercury is released as smoke into the atmosphere. Most of this mercury pollution can be eliminated if pollution-control devices are installed.[7]

Current advice

The complexities associated with mercury transport and environmental fate are described by USEPA in their 1997 Mercury Study Report to Congress.[8] Because methylmercury and high levels of elemental mercury can be particularly toxic to a fetus or young children, organizations such as the U.S. EPA and FDA recommend that women who are pregnant or plan to become pregnant within the next one or two years, as well as young children avoid eating more than 6 ounces (one average meal) of fish per week.[9]

In the United States, the FDA has an action level for methylmercury in commercial marine and freshwater fish that is 1.0 parts per million (ppm). In Canada, the limit for the total of mercury content is 0.5 ppm. The Got Mercury? website includes a calculator for determining mercury levels in fish.[10]

Species with characteristically low levels of mercury include shrimp, tilapia, salmon, pollock, and catfish (FDA March 2004). The FDA characterizes shrimp, catfish, pollock, salmon, sardines, and canned light tuna as low-mercury seafood, although recent tests have indicated that up to 6 percent of canned light tuna may contain high levels.[11] A study published in 2008 found that mercury distribution in tuna meat is inversely related to the lipid content, suggesting that the lipid concentration within edible tuna tissues has a diluting effect on mercury content.[12] These findings suggest that choosing to consume a type of tuna that has a higher natural fat content may help reduce the amount of mercury intake, compared to consuming tuna with a low fat content. Also, many of the fish chosen for sushi contain high levels of mercury.[13]

According to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the risk from mercury by eating fish and shellfish shall not be a health concern for most people.[14] However, certain seafood might contain levels of mercury that may cause harm to an unborn baby (and especially its brain development and nervous system). In a young child, high levels of mercury can interfere with the development of the nervous system. The FDA provides three recommendations for young children, pregnant women, and women of child-bearing age:

- Do not eat shark, swordfish, king mackerel, or tilefish because they might contain high levels of mercury.

- Eat up to 12 ounces (2 average meals) a week of a variety of fish and shellfish that are lower in mercury. Five of the most commonly eaten fish and shellfish that are low in mercury are: shrimp, canned light tuna, salmon, pollock, and catfish. Another commonly eaten fish, albacore or big eye ("white") tuna depending on its origin might have more mercury than canned light tuna. So, when choosing your two meals of fish and shellfish, it is recommended that you should not eat more than up to 6 ounces (one average meal) of albacore tuna per week.

- Check local advisories about the safety of fish caught by family and friends in your local lakes, rivers, and coastal areas. If no advice is available, eat up to 6 ounces (one average meal) per week of fish you catch from local waters, but consume no other fish during that week.

Background

In the 1950s, inhabitants of the seaside town of Minamata, on Kyushu island in Japan, noticed strange behavior in animals. Cats would exhibit nervous tremors, dance and scream. Within a few years this was observed in other animals; birds would drop out of the sky. Symptoms were also observed in fish, an important component of the diet, especially for the poor. When human symptoms started to be noticed around 1956 an investigation began. Fishing was officially banned in 1957. It was found that the Chisso Corporation, a petrochemical company and maker of plastics such as vinyl chloride, had been discharging heavy metal waste into the sea. They used mercury compounds as catalysts in their syntheses. It is believed that about 5,000 people were killed and perhaps 50,000 have been to some extent poisoned by mercury. Mercury poisoning in Minamata, Japan, is now known as Minamata disease.

A book by Jane Hightower, Diagnosis Mercury: Money, Politics and Poison, published in 2008, discusses human exposure to mercury through eating large predatory fish such as swordfish, shark, king mackerel, large tuna, etc.[15][16][17]

See also

- Friend of the Sea

- Got Mercury?

- Mercury cycle

- Mercury in tuna

- Safe Harbor Certified Seafood

- Seafood Watch, sustainable consumer guide (USA)

- Sustainable seafood

Notes

- ^ Mercury Levels in Commercial Fish and Shellfish (1990-2010). United States Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved July 1, 2011.

- ^ Croteau, M., S. N. Luoma, and A. R Stewart. 2005. Trophic transfer of metals along freshwater food webs: Evidence of cadmium biomagnification in nature. Limnol. Oceanogr. 50 (5): 1511-1519.

- ^ Cocoros, G.; Cahn, P. H.; Siler, W. (1973). "Mercury concentrations in fish, plankton and water from three Western Atlantic estuaries". Journal of Fish Biology 5 (6): 641–647. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8649.1973.tb04500.x. http://www.feedmethefacts.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/04/cocoros_and_cahn_19731.pdf.

- ^ EPA (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency). 1997. Mercury Study Report to Congress. Vol. IV: An Assessment of Exposure to Mercury in the United States . EPA-452/R-97-006. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Air Quality Planning and Standards and Office of Research and Development.

- ^ a b New York Times, 2009 Aug. 19, "Mercury Found in Every Fish Tested, Scientists Say,"

- ^ FDA mercury levels in fish and shellfish [1]

- ^ a b Mercury contamination in fish: Know where it's coming from Natural Resources Defense Council. Retrieved 23 January 2010

- ^ EPA (1997). "Mercury Study Report to Congress". http://www.epa.gov/mercury/report.htm. Retrieved January 23, 2008.

- ^ FDA/EPA (2004). "What You Need to Know About Mercury in Fish and Shellfish". http://www.cfsan.fda.gov/~dms/admehg3.html. Retrieved October 25, 2006.

- ^ "Got Mercury? Online Calculator Helps Seafood Consumers Gauge Mercury Intake". Common Dreams. March 9, 2004. http://www.commondreams.org/news2004/0310-02.htm. Retrieved 2008-03-30.

- ^ "FDA tests show risk in tuna". Chicago Tribune. January 27, 2006. http://www.chicagotribune.com/features/health/chi-0601270193jan27,1,7450296.story. Retrieved 2007-05-01.

- ^ Balshaw, S.; J.W. Edwards, K.E. Ross, and B.J. Daughtry (December 2008). "Mercury distribution in the muscular tissue of farmed southern bluefin tuna (Thunnus maccoyii) is inversely related to the lipid content of tissues". Food Chemistry 111 (3): 616–621. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.04.041. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=ArticleURL&_udi=B6T6R-4SBY4YP-1&_user=10&_coverDate=12%2F01%2F2008&_rdoc=1&_fmt=high&_orig=search&_sort=d&_docanchor=&view=c&_searchStrId=1274914421&_rerunOrigin=google&_acct=C000050221&_version=1&_urlVersion=0&_userid=10&md5=47ba5949faf1e1a3fc0e071896f6eeb7. Retrieved March 30, 2010.

- ^ "NRDC: Mercury Contamination in Fish - Guide to Mercury in Sushi". http://www.nrdc.org/health/effects/mercury/sushi.asp.

- ^ What You Need to Know About Mercury in Fish and Shellfish

- ^ Jane Hightower (2008). Diagnosis Mercury: Money, Politics and Poison, Island Press, p. 250.

- ^ Review: Diagnosis: Mercury by Jane Hightower

- ^ Diagnosis Mercury: Money, Politics and Poison by Jane M. Hightower

External links

- Health policy for pregnant women The NRDC created the chart below as a guideline to how much tuna can be eaten by children, pregnant women or women wanting to conceive, based on their weight.

- Recommendations for Fish Consumption in Alaska Bulletin No. 6 June 15, 2001 Mercury and National Fish Advisories Statement from Alaska Division of Public Health

- Methylmercury in Sport Fish: Information for Fish Consumers

- FDA Tests Show Mercury in White Tuna 3 Times Higher than Can Light, Says Mercury Policy Project

- FDA - Mercury Levels in Commercial Fish and Shellfish

- Federal Study Shows Mercury In Fish Widespread, Inescapable

- Healthy Sushi selector

- Find a healthy fish for consumption

- Smart and healthy choices when consuming seafood

Marine pollution - Algal bloom

- Anoxic event

- Anoxic waters

- Aquatic toxicology

- Cultural eutrophication

- Cyanotoxin

- Environmental impact of shipping

- Eutrophication

- Fish diseases and parasites

- Fish kill

- Friendly Floatees

- Great Pacific Garbage Patch

- Hypoxia

- Invasive species

- Marine debris

- Mercury in fish

- Nonpoint source pollution

- North Atlantic Garbage Patch

- Nutrient pollution

- Ocean acidification

- Ocean deoxygenation

- Oil spill

- Particle

- Plastic particle water pollution

- Point source pollution

- Shutdown of thermohaline circulation

- Stormwater

- Surface runoff

- Upwelling

- Urban runoff

- Water pollution

Fisheries science and wild fisheries Fisheries science - Population dynamics of fisheries

- Shifting baseline

- Fish stock

- Fish mortality

- Stock assessment

- Fish measurement

- Fish counter

- Data storage tag

- Biomass

- Fisheries acoustics

- Acoustic tag

- GIS and aquatic science

- EcoSCOPE

- Age class structure

- Trophic level

- Trophic cascades

- Match/mismatch hypothesis

- Fisheries and climate change

- Marine biology

- Aquatic ecosystems

- Bioeconomics

- EconMult

- Ecopath

- FishBase

- Census of Marine Life

- OSTM

- Fisheries databases

- Institutes

- Fisheries scientists

Wild fisheries - Ocean fisheries

- Diversity of fish

- Coastal fish

- Coral reef fish

- Demersal fish

- Forage fish

- Pelagic fish

- Cod fisheries

- Crab fisheries

- Eel fisheries

- Krill fisheries

- Kelp fisheries

- Lobster fisheries

- Shrimp fisheries

- Eel ladder

- Fish ladder

- Fish screen

- Migration

- Sardine run

- Shoaling and schooling

- Marine habitats

- Marine snow

- Water column

- Upwelling

- Humboldt current

- Algal blooms

- Dead zones

- Fish kill

Fisheries management, sustainability and conservation Management

Quotas Sustainability - Sustainable fisheries

- Maximum sustainable yield

- Sustainable seafood

- Overfishing

- Environmental effects of fishing

- Fishing down the food web

- Destructive fishing practices

- Future of Marine Animal Populations

- The Sunken Billions

- End of the Line

Conservation - Marine Protected Area

- Marine reserve

- Marine conservation

- Marine conservation activism

- Salmon conservation

- Grey nurse shark conservation

- Shark sanctuary

Organisations - Marine Stewardship Council

- Friend of the Sea

- SeaChoice

- Seafood Watch

- Oceana

- Sea Around Us Project

- WorldFish Center

- Defying Ocean's End

- HERMIONE

- PROFISH

- International Seafood Sustainability Foundation

- Sea Shepherd Conservation Society

- Greenpeace

Related issues - CalCOFI

- Marine pollution

- Mercury in fish

- Shark finning

- List of fishing topics by subject

- Index of fishing articles

- Fisheries glossary

Categories:- Environmental issues with fishing

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.