- Marxism–Leninism

-

Part of a series on Marxism–Leninism  Core tenets· Central planning

Core tenets· Central planning

· Communism

· Democratic centralism

· Market socialism

· Single party state

· Socialist patriotism

· Vanguard partyTopicsWorks· Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism

· The State and Revolution

· Dialectical and Historical Materialism

· On Contradiction

· Guerrilla WarfareHistory· Soviet Union

· Comintern

· Spanish Civil War

· World War II

· Warsaw Pact

· Greek Civil War

· Chinese Revolution (1949)

· Korean War

· Cuban Revolution

· De-Stalinization

· Non-Aligned Movement

· Sino-Soviet Split

· Vietnam War

· Portuguese Colonial War

· Nicaraguan Revolution

· Revolutions of 1989

· Nepalese Civil War

· Naxalite-Maoist insurgencyLists· List of Marxist-Leninist movementsCommunism Portal

Politics portalMarxism–Leninism is a communist ideology, officially based upon the theories of Marxism and Vladimir Lenin, that promotes the development and creation of international communist society through the leadership of a vanguard party over a revolutionary socialist state that represents a dictatorship of the proletariat.[1] Marxist-Leninist society seeks to purge anything considered bourgeois, idealist, or religious from it.[2] It supports the creation of a totalitarian single-party state.[3][4] It rejects political pluralism external to communism, claiming that the proletariat need a single, able political party to represent them and exercise political leadership.[5] The Marxist-Leninist state forbids opposition to itself and its ideology.[6] Through the policy of democratic centralism, the communist party is the supreme political institution of the Marxist-Leninist state.[3]

Marxism–Leninism is a far-left ideology. It is based on principles of class conflict, egalitarianism, dialectical materialism and rationalism, as well as social progress. It is anti-bourgeois, anti-capitalist, anti-conservative, anti-fascist, anti-imperialist, anti-liberal, anti-reactionary, can be opposed to the revisionism of Marxism, and is opposed to bourgeois democracy.

The Marxism-Leninist state utilizes a centrally planned state socialist economy.[6] It supports public ownership of the economy and supports the confiscation of almost all private property that becomes public property administered by the state, while a minuscule portion of private property is allowed to remain.[7] It typically replaces the role of market in the capitalist economy with centralized state management of the economy that is known as a command economy.[7] However an alternative Marxist-Leninist economy that exists is the market socialist economy that has been used by the People's Republic of China, and historically by the People's Republic of Hungary and the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia.

Etymology

Historical usage

Within five years of Vladmir Lenin's death in 1924, Stalin completed his rise to power in the Soviet Union. According to G. Lisichkin, Marxism–Leninism as a separate ideology was compiled by Stalin in his book "The questions of Leninism".[8] During the period of Stalin's rule in the Soviet Union, Marxism–Leninism was proclaimed the official ideology of the state.[9]

Whether Stalin's practices actually followed the principles of Karl Marx and Lenin is still a subject of debate among historians and political scientists.[10] Trotskyists in particular believe that Stalinism contradicted authentic Marxism and Leninism,[11] and they initially used the term "Bolshevik–Leninism" to describe their own ideology of anti-Stalinist (and later anti-Maoist) communism. Left communists rejected "Marxism–Leninism" as an anti-Marxist current.[citation needed]

The term "Marxism–Leninism" is most often used by those who believe that Lenin's legacy was successfully carried forward by Joseph Stalin (Stalinists). However, it is also used by some who repudiate Stalin, such as the supporters of Nikita Khrushchev.[12]

After the Sino–Soviet split, communist parties of the Soviet Union and the People's Republic of China each claimed to be the sole intellectual heir to Marxism–Leninism. In China, the claim that Mao had "adapted Marxism–Leninism to Chinese conditions" evolved into the idea that he had updated it in a fundamental way applying to the world as a whole; consequently, the term "Marxism–Leninism–Mao Zedong Thought" (commonly known as Maoism) was increasingly used to describe the official Chinese state ideology as well as the ideological basis of parties around the world who sympathized with the Communist Party of China (such as the Communist Party of the Philippines, Marxist–Leninist/Mao Zedong Thought, founded by Jose Maria Sison in 1968). Following the death of Mao, Peruvian Maoists associated with the Communist Party of Peru (Sendero Luminoso) subsequently coined the term Marxism–Leninism–Maoism, arguing that Maoism was a more advanced stage of Marxism.

Following the Sino–Albanian split, a small portion of Marxist–Leninists began to downplay or repudiate the role of Mao Zedong in the International Communist Movement in favor of the Party of Labor of Albania and a stricter adherence to Stalin.

In North Korea, Marxism–Leninism was officially superseded in 1977 by Juche, in which concepts of class and class struggle, in other words Marxism itself, play no significant role. However, the government is still sometimes referred to as Marxist–Leninist—or, more commonly, Stalinist—due to its political and economic structure (see History of North Korea).

In the other four communist states existing today—Cuba, Nepal, Laos, and Vietnam—the ruling Parties hold Marxism–Leninism as their official ideology, although they give it different interpretations in terms of practical policy.

Current usage

Some contemporary communist parties continue to regard Marxism–Leninism as their basic ideology, although some have modified it to adapt to new and local political circumstances.

In party names, the appellation "Marxist–Leninist" is normally used by a communist party who wishes to distinguish itself from some other (and presumably 'revisionist') communist party in the same country.

Popular confusion abounds concerning the complex terminology describing the various schools of Marxist-derived thought. The appellation "Marxist–Leninist" is often used by those not familiar with communist ideology in any detail (e.g. many newspapers and other media) as a synonym for any kind of Marxism.

Components

Social

Social policy in Marxist-Leninist states is typically utopian, transformatory, and totalitarian.[13] Marxist-Leninist social policy has often been dedicated to promoting and reinforcing the operation of a planned socialist economy.[13] Improvements in public health and education, provision of child care, provision of state-directed social services, and provision of social benefits are deemed by Marxist-Leninists to help to raise labour productivity.[13] The historical Marxist-Leninist states of Central and Eastern Europe treated housing, education, health care, and child care as universal social entitlements.[14] The People's Republic of China has promised its citizens the right to the basic amenities of life—food, shelter, health care, and education.[15]

In the first years of the Soviet republic in Russia, the Bolshevik government enacted radical policies for that time, it overhauled family law: abortion and divorce were legalized, children born out of wedlock were given equal rights to those born to married parents; domestic servants were organized into trade unions; and social service centres, such as day care centres, were directed to promote a communal form of social existence.[13] Upon legalizing divorce, by the mid-1920s the Soviet Union had the highest divorce rate in Europe.[16] However Stalin later substantially restricted abortion and divorce to promote pronatalist policies.[13] Religious marriage was abolished and secularized civil marriage was permitted and the traditional religious marriage concept of matrimony, involving the transfer of a woman's legal and economic dependence from her family of origin to her husband's was abolished.[17] Marriage was defined as a "free and voluntary union" of two individuals enjoying equal rights.[17] Marxist-Leninist regimes that developed after World War II followed the Soviet model on family law with the goals of: the elimination of the political power of the bourgeoisie, the abolition of private property, and an education that taught citizens to abide by a disiciplined and a regulated lifestyle dictated by the norms of communism as a means to establish a new social order.[18] After the death of Stalin, the Soviet Union reduced the political ideological emphasis on family policy and focused on the national character of family.[18]

Marxism-Leninist states have advocated widespread universal social welfare programs.[19] Soviet law provided pensions for workers to retire at the age of fifty-five for women and the age of sixty for men.[14] Soviet law officially demanded sanitary housing with a norm of nine square metres per person, though very little housing achieved this until the 1960s.[14] The historical Marxist-Leninist states of Central and Eastern Europe generally followed the Soviet model of social welfare.[14]

Marxism–Leninism advocates universal education with a focus on developing the proletariat with knowledge, class consciousness, and understanding and support for communism.[20]

Marxism–Leninism supports the emancipation of women and ending the exploitation of women.[21] The advent of a classless society, the abolition of private property, society collectively assuming many of the roles traditionally assigned to mothers and wives, and women becoming integrated into industrial work has been promoted as the means to achieve women's emancipation.[22] Women's committees have been set up in in communist parties since 1920 under the influence of German communist Clara Zetkin.[23] The Soviet Union recognized the "double burden" of housework and paid employment for women.[14] Soviet law encouraged women to work outside the home and a high rate of female workforce participation was achieved in the Soviet Union.[14] However the Soviet Union continued to view housework as a woman's responsibility.[14] Data by the United Nations indicates that the Soviet Union in 1970 had the highest percentage of employed women in the world.[24]

Marxist-Leninist cultural policy has focused upon modernization and distancing society from: the past, the bourgeoisie, and the old intelligentsia.[25] Agitprop and various associations and institutions are used by the Marxist-Leninist state to indoctrinate society with the values of communism.[26] Marxist-Leninist cultural policy affects popular culture, as Soviet popular culture included "Red" comic strips and "Red" detective stories.[26] During Stalin's regime rigid requirements and restrictions were placed on art and culture to enforce conformity, obedience, and to promote the regime's ideals in what was known as Socialist Realism that promoted social harmony and portray hope of a bright future under communism.[27] De-Stalinization in the Soviet Union involved liberalization of cultural policy, including the ending Socialist Realist requirements, and public debate, discussion, and doubt over Soviet policies was allowed.[27] However these freedoms did not last long before they were revoked under Brezhnev and Soviet cultural policy returned to be restrictive until the policies of Perestroika were introduced by Mikhail Gorbachev.[28]

Both cultural and educational policy in Marxist-Leninist states have emphasized the development of a "New Man" - an ideal class conscious, knowledgible, heroic proletarian person devoted to work and collectivism as opposed to the unideal "bourgeois individualist" associated with cultural backwardness.[29] The Soviet Union under Stalin with its productivist economic orientation emphasized a New Man based upon productivity with dedicated workers being considered "heroes of labour", "heroes of socialism", or "constructors of a new world".[29] Later the Soviet Union also included its soldiers of World War II who fought against Nazi Germany as such New Men.[30]

The People's Republic of China created the Cultural Revolution in the late 1960s that continued until 1977 that called for an escalation of measures to eliminate the remains of capitalism in the country through progressive mass mobilization, cultural iconoclasm of non-communist culture, and mass violence against the bourgeoisie, including alleged bourgeois infiltrators of the Communist Party of China.[31] Mao Zedong permitted the unleashing of mass violence in the late 1960s against specific alleged enemy infiltrators within the Communist Party and the government.[31] The remainder of the Cultural Revolution was the defense by Mao and his supporters of Maoism and attacking former allies whom were deemed to be "right-wing deviationists" of Maoism, including Deng Xiaoping.[28] Following Mao's death the third and final phase of the Cultural Revolution was declared to be over in 1977.[32]

Economic

A central component of most Marxist-Leninist economics is the command economy.[33] Originally, under Lenin and later Stalin, the command economy was not initially used, with war communism and the New Economic Policy as its predecessors, until it became predominant by 1930.[34] Under a command economy, the Marxist-Leninist state owns most of the capital and the land of a territory, it is a planned economy where state planning replaces market mechanisms and price mechanisms as the guiding principle of the economy.[33] The state set long-term plans for the economy, including setting production targets and coordinated various aspects of the economy.[33] The Marxist-Leninist state's huge purchasing power in theory replaces the role of market forces, with macroeconomic equilibrium not being achieved through market forces but by government intervention.[34] State commands replace the profit motive.[34] The command economy permits a small amount of private property to remain for necessary personal use.[35] Wages are set and differentiated according to skill and intensity of work.[35] In the Soviet Union, consumer goods were only rationed between 1930–1935 and 1941–1947, otherwise consumers could freely spend their income in either the state-owned economic sector or the free market.[35] In state-owned retail trade, prices are fixed at a certain rates, though authorities seek to balance supply and demand, including through "turnover taxes".[35] In the Soviet Union, the command economy brought about massive industrialization but at the expense of agriculture that declined drastically between 1928 and 1940.[35]

The People's Republic of China officially has the command economy system and exercises major state control over the economy, however the economic reforms that began with Deng Xiaoping have opened up a major private enterprise market economy in the country.[35]

Marxism–Leninism has pursued different specific labour policies in different countries and has varied over time .[36] The system of the Soviet Union the Stalinist policies of rapid industrialization resulted in both incentives and coercion being used to bring workers in line with state policy.[36]

Marxism–Leninism since mid-1930s has advocated a socialist consumer society based upon egalitarianism, asceticism, and self-sacrifice.[37] Previous attempts to replace the consumer society as derived from capitalism with a non-consumerist society failed and in the mid-1930s permitted a consumer society, a major change from traditional Marxism's anti-market and anti-consumerist theories.[37] These reforms were promoted to encourage materialism and acquisitiveness in order to stimulate people to work better and achieve economic growth.[37] This pro-consumerist policy has been advanced on the lines of "industrial pragmatism" as it advances economic progress through bolstering industrialization.[38]

Justice and Security

The Soviet Union utilized an extensive network of secret police, agents, and informants through its intelligence agency known as the KGB (originally known as the Cheka, and later the NKVD and other organizations) whose principal duties were the prevention of counterrevolution, the prevention of sabotage, and incarceration and/or liquidation of political enemies.[39] Its original predecessor, the Cheka had been created only as a temporary institution that was supposed to be dissolved after political enemies had been liquidated and the regime had consolidated its power, however this was not done.[39] Instead the Cheka took over control of prisoners from the People's Commissariat of Justice (NKJu) and put them in labour camps.[39] The Cheka was succeeded by the NKVD and OGPU in which the later merged into the NKVD in 1934, and during their existence concentration camps that were named "work and reeducation camps" that utilized forced labour of criminals and political prisoners for state building projects.[40] The NKVD took part in the Great Terror campaign of Stalin against alleged "socially dangerous" and "counterrevolutionary" persons that resulted in the Great Purge of 1936-1938 during which 1.5 million people were arrested from 1937–1938 and 681,692 of those were executed.[41] In 1938, the Gulag system of forced labour camps was set up under the auspices of the NKVD.[41] The KGB's creation in 1954 resulted in some limitations being placed on the organization's authority and powers in which the Prosecutor's Office could oversee and correct the KGB's work and the political crimes of "enemy of the people" and "counterrevolutionary crimes" were eliminated.[42] However the KGB's powers increased in 1961, and created a new category of "economic crimes".[39]

Political structure

Marxism–Leninism supports the creation of a totalitarian single-party state led by a Marxist-Leninist communist party as a means to develop socialism and then communism.[3][4] The political structure of the Marxist-Leninist state involves the rule of a communist vanguard party over a revolutionary socialist state that represents the will and rule of the proletariat.[1] Through the policy of democratic centralism, the communist party is the supreme political institution of the Marxist-Leninist state.[3]

Elections are held in Marxist-Leninist states for all positions within the legislative structure, municipal councils, national legislatures and presidencies.[43] In most Marxist-Leninist states this has taken the form of directly electing representatiives to fill positions, though in some states; such as China, Cuba, and the former Yugoslavia; this system also included indirect elections such as deputies being elected by deputies as the next lower level of government.[43] These elections are not competitive multiparty elections and most are not multi-candidate elections; usually a single communist party candidate is chosen to run for office in which voters vote either to accept or reject the candidate.[43] Where there have been more than one candidates, all candidates are officially vetted before being able to stand for candidacy and the system has frequently been structured to give advantage to official candidates over others.[43] Marxism–Leninism asserts that society is united upon common interests represented through the Ccmmunist party and other institutions of the Marxist-Leninist state and in Marxist-Leninist states where opposition political parties have been permitted they have not been permitted to advocate political platforms significantly different from the communist party.[43] The communist party has typically exercised close control over the electoral process, involved with nomination, campaigning, and voting - including counting the ballots.[43]

International relations

Marxism–Leninism opposes colonialism and imperialism and advocates decolonization and anti-colonial forces.[44] The Soviet Union and its Eastern bloc consistently supported anticolonial movements even if such movements were not led by communist or Marxist forces because it was believed that the erosion of colonial rule would cause the erosion of capitalism.[44] Opposition to the Warsaw Pact by the more neutral Marxist-Leninist Yugoslavia resulted in Yugoslavia forming the Non-Aligned Movement of states that rejected association with either the eastern or western blocs of the Cold War and sought a neutral position.[44]

The Soviet Union accepted many of the immediate post-colonial governments as being "friendly" "national-bourgeoisie" regimes, that because of the popular "national-" prefix were tolerable bourgeois regimes that held a tendency to cut colonial or neocolonial ties.[45] The Soviet Union believed that the proletariat could not carry out a successful revolution in colonized countries and thus required an initial anti-colonial revolution supported by the bourgeoisie to allow a future communist revolution.[45] It provided weapons, logistical support, and political cover for anti-colonial revolutionaries.[46]

Marxism–Leninism supports anti-fascist international alliances and has advocated the creation of "popular fronts" between communist and non-communist anti-fascists against strong fascist movements.[47]

The People's Republic of China focused on developing an Afro-Asian anticolonial movement and accused the Soviet Union of not committing all of its resourced in favour of a global communist revolution.[45] This criticism by the PRC involves the lack of substantial Soviet aide to its Middle Eastern and African allies and by its toleration of the U.S. war in Vietnam.[45]

History

Founding of Bolshevism, 1905–1907 Russian Revolution, and World War I (1903–1917)

Vladimir Lenin. Leader of both the RSFSR and the Soviet Union from 1917 to 1924.

Vladimir Lenin. Leader of both the RSFSR and the Soviet Union from 1917 to 1924.

Marxism–Leninism is the descendant of interpretation of the theories of Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, and Vladimir Lenin. It was officially created after Lenin's death during the regime of Josef Stalin in the Soviet Union and continued to be the official ideology of the Soviet Communist Party after de-Stalinization. However the basis for elements of Marxism–Leninism predate this. Marxism–Leninism descends from the Bolshevik ("Majority") faction of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) that was founded in the RSDLP's Second Congress in 1903.[48] The Bolshevik faction led by Lenin advocated an active, politically committed vanguard party membership while opposing trade union based membership of social democratic parties.[49] The Bolsheviks supported a vanguard Marxist party composed of active militants committed to socialism who would initiate communist revolution.[49] The Bolsheviks advocated the policy of democratic centralism that would allow members to elect their leaders and decide policy but that once policy was set, members would be obligated to have complete loyalty in their leaders.[49]

Lenin attempted and failed to bring about communist revolution in Russia in the Russian Revolution of 1905-7.[50] During the revolution, Lenin advocated mass action and that the revolution "accept mass terror in its tactics".[51] During the revolution Lenin advocated militancy and violence of workers as a means to pressure the middle class to join and overthrow the Tsar.[52] Bolshevik emigres briefly poured into Russia to take part in the revolution. Prior and after the failed revolution, the Bolshevik leadership voluntarily resided in exile to evade Tsarist Russia's secret police, such as Lenin who resided in Switzerland.[53] Most importantly, the experience of this revolution caused Lenin to conceive of the means of sponsoring communist revolution, through propaganda, agitation, a well-organized and disciplined but small political party, and through psychological manipulation of aroused masses.[53]

In the aftermath of the failed revolution of 1905-7, Bolshevik revolutionaries were forced back into exile in 1908 in Switzerland as well as other anti-Tsarist revolutionaries including the Mensheviks, the Socialist Revolutionaries, and anarchists.[54] Membership in both the Bolshevik and Menshevik ranks diminished from 1907 to 1908 and the number of people taking part in strikes in 1907 was 26 percent of the figure during the year of the revolution in 1905, it dropped in 1908 to 6 percent of that figure, and in 1910 it was 2 percent of that figure.[55] The period of 1908 to 1917 was one of dissillusionment in the Bolshevik party over Lenin's leadership, with members opposing him for scandals involving his expropriations and methods of raising money for the party.[55] One important development after the events the 1905-7 revolution was Lenin's endorsement of colonial revolt as a powerful reenforcement to revolution in Europe.[56] This was an original development by Lenin, as prior to the 1900s Marxists did not pay serious attention to colonialism and colonial revolt.[56] Facing leadership challenges from the "Forward" group, Lenin usurped the all-Party Congress of the RSDLP in 1912, to seize control of it and make it an exclusively Bolshevik party loyal to his leadership.[57] Almost all the members elected to the party's Central Committee were Leninists while former RDSLP leaders not associated with Bolshevism were removed from office.[58] Lenin remained highly unpopular in the early 1910s, and was so unpopular amongst international socialist movement that by 1914 it considered censoring him.[55]

At the outset of World War I in 1914, the Bolsheviks opposed the war unlike most other socialist parties across Europe that supported their national governments.[59] Lenin and a small group of anti-war socialist leaders, including Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht, denounced established socialist leaders of having betrayed the socialist ideal via their support of the war.[59] In response to the outbreak of World War I, Lenin wrote his book Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism from 1915 to 1916 and published in 1917 in which he argued that capitalism directly leads to imperialism.[60] As a means to destabilize Russia on the Eastern Front, Germany's High Command allowed Lenin to travel across Germany and German-held territory into Russia in April 1917, anticipating him partaking in revolutionary activity.[61]

October Revolution, aftermath conflict, and the creation of the Soviet Union (1917–1924)

In March 1917, Tsar Nicholas II abdicated his throne and a Provisional Government quickly filled the vacuum, proclaiming Russia a republic months later. This was followed by the October Revolution by the Bolsheviks, who seized control in a quick coup d'état against the Provisional Government, resulting in the formation of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR), the first country in history committed to the establishment of communism. However large portions of Russia were held under the leadership of either pro-Tsarist or anti-communist military commanders who formed the White movement to oppose the Bolsheviks, resulting in civil war between the Bolsheviks' Red Army and the anti-Bolshevik White Army. Amidst civil war between the Reds and the Whites, the RSFSR inheritted the war that the Russian Empire was fighting against Germany that was ended a year later with an armistice. However this was followed by a brief Allied military intervention by the United Kingdom, the United States, France, Italy, Japan and others against the Bolsheviks.[62]

In response to the October Revolution, communist revolution broke out in Germany and Hungary from 1918 to 1920, involving creation of the Bavarian Soviet Republic, the failed Spartacist uprising in Berlin in 1919, and the creation of the Hungarian Soviet Republic. These communist forces were soon crushed by anti-communist forces and attempts to create an international communist revolution failed. However a successful communist revolution occurred in Mongolia in 1924, resulting in the creation of the Mongolian People's Republic.

Lenin making a speech to a crowd in Sverdlov Square in Moscow on 5 May 1920. Leon Trotsky stands near Lenin to the right of the podium in uniform - in the Stalinist era this picture was edited to remove Trotsky.

Lenin making a speech to a crowd in Sverdlov Square in Moscow on 5 May 1920. Leon Trotsky stands near Lenin to the right of the podium in uniform - in the Stalinist era this picture was edited to remove Trotsky.

The entrenchment of Bolshevik power began in 1918 with the expulsion of Mensheviks and Socialist Revolutionaries from the workers' soviets.[63] The Bolshevik government established the Cheka, a secret police force dedicated to confronting anti-Bolshevik elements. The Cheka was the predacessor to the NKVD and the KGB. Initially opposition to the Bolshevik regime was strong as a response to Russia's poor economic conditions, with the Cheka reporting no less than 118 uprisings, including the Kronstadt Revolt.[63] Lenin repressed opposition political parties.[63] Intense political struggle continued until 1922.[63]

Initial Bolshevik economic policies from 1917 to 1918 were cautious with limited nationalizations of private property.[64] Lenin was immediately committed to avoid antagonizing the peasantry by making efforts to coax them away from the Socialist Revolutionaries, allowing a peasant takeover of nobles' estates while no immediate nationalizations were enacted on peasants' property.[64] Beginning in mid-1918, the Bolshevik regime enacted what is known as "war communism", an economic policy that aimed to replace the free market with state control over all means of production and distribution.[64] This was done through the Decree on Nationalization that declared the nationalization of all large-scale private enterprises while requisitioning grain away from peasants and providing it to workers in cities and Red soldiers fighting the Whites.[64] The result was economic chaos as the monetary economy collapsed and was replaced by barter and black marketeering.[64] The requisitioning of grain away from the peasantry to workers resulted in peasants losing incentive to labour resulting in a drop in production, producing a food shortage crisis in the cities that provoked strikes and riots that seriously challenged the Bolshevik regime, with the most serious being the Kronstadt Revolt of 1921.[64]

The New Economic Policy was started in 1921 as a backwards step from war communism, with the restoration of a degree of capitalism and private enterprise.[64] 91 percent of industrial enterprises were returned to private ownership or trusts.[64] Importantly, Lenin declared that the development of socialism would not be able to be pursued in the manner originally thought by Marxists.[64] Lenin stated "Our poverty is so great that we cannot at one stroke restore full-scale factory, state, socialist production".[64] A key aspect that affected the Bolshevik regime was the backward economic conditions in Russia that were considered unfavourable to orthodox Marxist theory of communist revolution.[50] Orthodox Marxists claimed at the time that Russia was ripe for the development of capitalism, not yet for socialism.[65] Lenin advocated the need of the development of a large corps of technical intelligentsia to assist the industrial development of Russia and thus advance the Marxist economic stages of development, as it had too few technical experts at the time.[50] The New Economic Policy was tultmultous, economic recovery took place but alongside famine (1921—1922) and a financial crisis (1924).[66] However by 1924, considerable economic progress had been achieved and by 1926 the economy regained its 1913 production level.[66]

Stalinism and World War II (1924–1945)

Joseph Stalin, leader of the Soviet Union, 1927-1953.

Joseph Stalin, leader of the Soviet Union, 1927-1953.

As Lenin neared death after suffering strokes, he declared in his testament of December 1922 an order to remove Joseph Stalin from his post as General Secretary and replaced by "some other person who is superior to Stalin only in one respect, namely, in being more tolerant, more loyal, more polite and more attentive to comrades".[67] When Lenin died in January 1924, the testament was read out to a meeting of the Party's Central Committee.[67] However Party members believed that Stalin had improved his reputation in 1923 and ignored Lenin's order.[68] Lev Kamenev and Grigory Zinoviev believed that the real threat to the party came from Trotsky, head of the Red Army, due to his association with the army and his powerful personality.[68] Kamenev and Zinoviev collaborated with Stalin in a power-sharing triumvirate where Stalin retained his position as General Secretary.[69] The confrontation between the triumverate and Trotsky began over the debate between the policy of Permanent Revolution as advocated by Trotsky and Socialism in One Country as advocated by Stalin.[69] Trotsky's Permanent Revolution advocated rapid industrialization, elimination of private farming, and having the Soviet Union promote the spread of communist revolution abroad.[70] Stalin's Socialism in One Country stressed moderation, development of positive relations between the Soviet Union and other countries to increase trade and foreign investment.[69] Stalin was not particularly committed to these positions, but used them as a means to isolate Trotsky.[70] In 1925, Stalin's policy won the support of the 14th Party Congress while Trotsky was defeated.[70]

From 1925 to 1927, Stalin abandoned his triumverate with Kamenev and Zinoviev and formed an alliance with the most rightest elements of the Party, Nikolai Bukharin, Alexei Rykov, and Mikhail Tomsky.[70] The 1927 Party Conference gave official endorsement to the policy of Socialism in One Country, while Trotsky along with Kamenev and Zinoviev (both now allied with Trotsky against Stalin) were expelled from the Party's Politburo.[70]

In 1929, Stalin seized control of the Party.[70] Upon Stalin attaining power, Bolshevism became associated with Stalinism, whose policies included: rapid industrialization, Socialism in One Country, a centralized state, collectivization of agriculture, and subordination of interests of other communist parties to those of the Soviet party.[49] In 1929 he enacted harsh radical policy towards the wealthy peasantry (Kulaks) and turned against Bukharin, Rykov, and Tomsky who favoured a more moderate approach to the Kulaks.[70] He accused them of plotting against the Party's agreed strategy and forced them to resign from the Politburo and political office.[70] Trotsky was exiled from the Soviet Union in 1929.[70] Opposition to Stalin by Trotsky led to a dissident Bolshevik ideology called Trotskyism that was repressed under Stalin's rule.[49]

Stalin's regime was an extreme totalitarian state under his dictatorship.[71] Stalin exercised extensive personal control over the Communist Party and unleashed an unprecedented level of violence to eliminate any potential threat to his regime.[71] While Stalin exercised major control over political initiatives, their implementation was in the control of localities, often with local leaders interpreting the policies in a way that served themselves best.[71] This abuse of power by local leaders exacerbated the violent purges and terror campaigns carried out by Stalin against members of the Party deemed to be traitors.[71] The Stalinist era saw the introduction of a system of forced labour of convicts and political dissidents, the Gulag system, of that created in the early 1930s.[72]

Political developments in the Soviet Union from 1929 to 1941 included Stalin dismantling the remaining elements of democracy from the Party by extending his control over its institutions and eliminating any possible rivals.[72] The Party's ranks grew in numbers with the Party modifying its organization to include more trade unions and factories.[72] In 1936, the Soviet Union adopted a new constitution that ended weighted voting preference for workers as in its previous constitutions, and created universal suffrage for all people over the age of eighteen.[72] The 1936 Constitution also split the Soviets into two legislatures, the Soviet of the Union - representing electoral districts, and the Soviet of the Nationalities - that represented the ethnic makeup of the country as a whole.[72] By 1939, with the exception of Stalin himself, none of the original Bolsheviks of the October Revolution of 1917 remained in the Party.[72] Unquestioning loyalty to Stalin was expected by the regime of all citizens.[72]

Economic developments in the Soviet Union from 1929 to 1941 included the acceleration of collectivization of agriculture.[72] In 1930, 23.6 percent of all agriculture was collectivized, by 1941, 98 percent of all agriculture was collectivized.[73] This process of collectivization included "dekulakization", in which kulaks were forced off their land, persecuted, and killed in a wave of terror unleashed by the Soviet state against them.[74] The collectivization policies resulted in economic disaster with severe fluctuations in grain harvests, catastrophic losses in the number of livestock, a substantial drop in the food consumption of the country's citizens, and the intentional Holodomor famine in the Ukraine.[75] Modern sources estimate that between 2.4[76] and 7.5[77] million Ukrainians died in the Holodomor famine. Vast industrialization was initiated, mostly based on the basis of preparation for an offensive war against the West - with a focus on heavy industry.[78] However even at its peak, industry of the Soviet Union remained well behind that of the United States.[79] Industrialization led to a massive urbanization in the country.[80] Unemployment was virtually eliminated in country during the 1930s.[80]

Social developments in the Soviet Union from 1929 to 1941 included the relinquishment of the relaxed social control and allowance of of experimentation under Lenin to Stalin's promotion of a rigid and authoritarian society based upon discipline - mixing traditional Russian values with Stalin's interpretation of Marxism.[79] Organized religion was repressed, especially minority religious groups.[79] Education was transformed, under Lenin, the education system took allowed relaxed discipline in schools that became based upon Marxist theory, but Stalin reversed this in 1934 with a conservative approach taken with the reintroduction of formal learning, the use of examinations and grades, the assertion of full authority of the teacher, and the introduction of school uniforms.[79] Art and culture became strictly regulated under the principles of Socialist Realism, and Russian traditions that Stalin admired were allowed to continue.[79]

Foreign policy in the Soviet Union from 1929 to 1941 resulted in substantial changes in the Soviet Union's approach to its foreign policy.[81] The rise of Adolf Hitler and the Nazis in Germany in 1933 resulted in the Soviet Union initially terminating the political connections it previously had established with Germany in the 1920s and Stalin turned to accommodate Czechoslovakia and the West against Hitler.[82] The Soviet Union promoted various anti-fascist fronts across Europe and created agreements with France to challenge Germany.[82] With the Suddeten agreement in 1938, Soviet foreign policy reversed, with Stalin abandoning anti-German policies and adopting pro-German policies.[82] In 1939, the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany agreed to both a non-aggression pact and an agreement to invade and partition Poland between them, resulting in the invasion of Poland in September 1939 by Germany and the Soviet Union and the beginning of World War II, with the Allies declaring war on Germany.[83]

The German invasion of the Soviet Union resulted in the substantial realignment of multiple Soviet policies. The Soviet Union was brought into World War II and joined the Western Allies in a common front against the Axis Powers. The war brought the threat of physical disintegration of the Soviet Union, as German forces were initially welcomed as liberators by many Belarussians, Georgians, and Ukrainians.[84] Soviet forces initially faced disastrous losses from 1941 to 1942.[84] Stalin enacted total war policy in response.[84]

Communist insurrection against Axis occupation took place in severa countries. In China, the Communist Party of China led by Mao Zedong reluctantly abandoned the civil war with the Kuomintang and cooperated with it against Japanese occupation forces. In Yugoslavia, the communist Yugoslav Partisans led by Josip Broz Tito held up an effective guerilla resistance movement to the Axis occupiers. The Partisans managed to form a communist Yugoslav state called Democratic Federal Yugoslavia in liberated territories in 1943 and by 1944, with the assistance of Soviet forces, seized control of Yugoslavia, entrenching a communist regime in Yugoslavia.

Soviet forces rebounded in 1943 with the victories at the Battle of Stalingrad and the Battle of Kursk, and from 1943 to 1945 they pushed back German forces and seiged Berlin in 1945.[85] By the end of World War II, the Soviet Union had become a major military superpower.[85] With the collapse of the Axis Powers, Soviet satellite states were established throughout Eastern Europe, creating a large communist bloc of states in Europe.

Cold War, de-Stalinization, and Maoism (1945–1985)

Tensions between the Western Allies and the communist Eastern allies accelerated after the end of World War II, resulting in the Cold War between the Soviet-led communist East and the American-led capitalist West. Key events that began the Cold War included Soviet, Yugoslav, Bulgarian, and Albanian intervention in the Greek civil war on the side of the communists, and the creation of the Berlin blockade by the Soviet Union in 1948. China returned to civil war between the Western-backed Kuomintang versus Mao Zedong's Communists supported by the Soviet Union with the Communists seizing control of all of mainland China in 1949, creating the People's Republic of China (PRC). Direct conflict between the East and West erupted in the Korean War, when the United Nations Security Council, with the absence of the Soviet Union at the time of the vote, voted for international intervention in Korea to stop the civil war. The United States and other Western powers used the war to prop up South Korea against Soviet and PRC-backed communist North Korea led by Kim Il-Sung. The war ended in armistice and stalemate in 1953.

Stalin's attempts to enforce submission of its Eastern European allies to the economic and political agenda of the Soviet Union sparked opposition and rejection in Yugoslavia by Tito. Stalin denounced Tito and removed Yugoslavia from the Comintern. Tito in return rejected Stalinism and the Eastern bloc, forging a non-aligned position between East and West that developed into the Non-Aligned Movement and the development of an autonomous Marxist-Leninist ideology of Titoism.

In 1953, Stalin died of a stroke, ending his 29 years of influence and rule over the Soviet Union.

With the death of Stalin in 1953, Nikita Khrushchev gradually accended to power in the Soviet Union and announced a radical policy of de-Stalinization of the Communist Party and the country, condemning Stalin for excesses and tyranny. Gulag forced labour camps were dismantled. Anti-Stalinist figures such as Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn were allowed the freedom to criticize Stalin. The cult of personality associated with Stalin was eliminated. Stalinists were removed from office. Khrushchev ended Stalin's policy of Socialism in One Country and committed the Soviet Union to actively support communist revolution throughout the world. The policies of de-Stalinization were promoted as an attempt to restore the legacy of Lenin. The death of Stalin, however did not result in the end of the Cold War. The conflict continued and excalated.

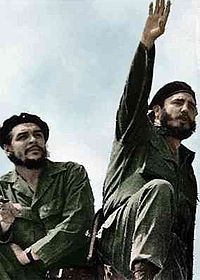

Argentine communist revolutionary Che Guevara (left) and Fidel Castro, leader of Cuba from 1959 to 2008.

Argentine communist revolutionary Che Guevara (left) and Fidel Castro, leader of Cuba from 1959 to 2008.

Communist revolution erupted in the Americas in this period, including revolutions in Bolivia, Cuba, El Salvador, Grenada, Nicaragua, Peru, and Uruguay. In Cuba in 1959, forces led by Fidel Castro and Argentine revolutionary Che Guevara overthrew the regime of Fulgencio Batista and established a communist regime there with ties to the Soviet Union. American attempts to overthrow the Castro regime with the failed Bay of Pigs Invasion by Cuban exiles supported by the CIA failed. Shortly afterwards, a diplomatic dispute erupted when the U.S. discovered Soviet nuclear missiles placed in Cuba, resulting in the Cuban Missile Crisis. The standoff between the two superpowers was resolved by the Soviet Union agreeing to remove its nuclear missiles from Cuba in exchange for the United States removing its nuclear missiles from Turkey. Bolivia faced Marxist-Leninist revolution in the 1960s that included Che Guevara as a leader until being killed there by government forces. Uruguay faced Marxist-Leninist revolution from the Tupamaros movement from the 1960s to the 1970s. A brief dramatic episode of Marxist-Leninist revolution took place in North America during the October Crisis in the province of Quebec in Canada, where the Marxist-Leninist and Quebec separatist Front de libération du Québec (FLQ) kidnapped the British Trade Commissioner in Canada, James Cross, and Quebec government minister Pierre Laporte who was later killed, it issued a manifesto condemning what it considered English Canadian imperialism in French Quebec calling for an independent, socialist Quebec. The Canadian government in response issued a crackdown on the FLQ and suspended civil liberties in Quebec, forcing the FLQ leadership to flee to exile in Cuba where the Cuban government accepted their entry. Daniel Ortega of the Marxist-Leninist movement called the Sandinista National Liberation Front seized power in Nicaragua in 1979 and faced armed opposition from the Contras supported by the United States. The United States launched military intervention in Grenada to prevent the establishment of a Marxist-Leninist regime there. The Salvadoran Civil War from 1980 to 1992 involved Marxist-Leninist rebels fighting against El Salvador's right-wing government.

Developments of Marxism–Leninism and communist revolution occurred in Asia in this period. The People's Republic of China under Mao Zedong developed its own unique brand of Marxism–Leninism known as Maoism. Tensions erupted between the PRC and the Soviet Union over a number of issues, including border disputes, resulting in the Sino-Soviet Split in the 1960s. After the split, the PRC eventually pursued detente with the United States as a means to challenge the Soviet Union. This was inaugurated with the visit of U.S. President Richard Nixon to the PRC in 1972 and the US supporting the PRC replacing the Republic of China as the representative of China at the United Nations and taking its seat at the UN Security Council. The death of Mao eventually saw the Deng Xiaoping politically outmaneuver Mao's chosen successor to power in the People's Republic of China. Deng made controversial economic reforms to the PRC's economy involving effective economic liberalization under the policy of Socialism with Chinese Characteristics. His reforms helped to gradually transform the PRC into one of the world's fastest growing economies. Another major conflict erupted between the East and West in the Cold War in Asia during the Vietnam War. French colonial forces had failed to hold back independence forces led by the communist leader Ho Chi Minh in North Vietnam. French forces retreated from Vietnam and were replaced by American forces supporting a Western-backed client regime in South Vietnam. Despite being a superpower and having a superior arsenal of weapons at its disposal, the United States was unable to make substantial gains against North Vietnam's proxy guerilla army in South Vietnam, the Viet Cong. With the direct intervention of North Vietnam in the South with the Tet Offensive of 1968, US forces suffered heavy losses. The American public turned against the war eventually resulting in a withdrawal of US troops and the seizure of Saigon by communist forces in 1975 and communist victory in Vietnam. Communist regimes were established in Vietnam's neighbour states in 1975, such as in Laos and the creation of the Khmer Rouge regime of Democratic Kampuchea (Cambodia). The Khmer Rouge regime became notorious for the mass genocide of the Cambodian population. The Khmer Rouge was overthrown in 1979 by an invasion by Vietnam that assisted the establishment of a new Marxist-Leninist regime, the People's Republic of Kampuchea, that opposed the policies of the Khmer Rouge.

A new front of Marxist-Leninist revolution erupted in Africa, with revolutions in Benin, Congo-Brazzaville, and Somalia; Marxist-Leninist liberation fronts in Angola and Mozambique revolting against Portguese colonial rule; the overthrow of Haile Selassie and the creation of the Derg communist military junta in Ethiopia; blacks led by Robert Mugabe in Rhodesia revolting against white-minority rule there. Angola, Benin, Congo-Brazzaville, Ethiopia, Mozambique, Somalia and Zimbabwe (formerly Rhodesia) all became Marxist-Leninist states between 1969 and 1979. Focus on apartheid white minority rule in South Africa brought tensions between East and West, the Soviet Union officially supported the overthrow of apartheid while the West and the US in particular maintained official neutrality on the matter. The Western position became precarious and condemned after the Soweto uprising in 1976 and the killing of black South African rights activist Steve Biko in 1977. Under US President Jimmy Carter, the West joined the Soviet Union and others in enacting sanctions against weapons trade and weapons-grade material to South Africa. However forceful actions by the US against apartheid South Africa were diminished under US President Ronald Reagan, as the Reagan administration feared the rise of communist revolution in South Africa as had happened in Zimbabwe against white minority rule.

In 1979, the Soviet Union intervened in Afghanistan to secure the communist regime there, though the act was seen as an invasion by Afghanis opposed to Afghanistan's communist regime and by the West. The West responded to the Soviet military actions by boycotting the Moscow Olympics of 1980 and providing clandestine support to the Mujahadeen, including Osama bin Laden, as a means to challenge the Soviet Union. The war became a Soviet equivelant of the Vietnam War to the United States - it remained a stalemate throughout the 1980s.

Reform and collapse of Marxist-Leninist regimes, end of the Cold War (1985–1992)

Soviet General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev in a meeting with US President Ronald Reagan. Gorbachev sought to end the Cold War between the Soviet-led Warsaw Pact and the US-led capitalist West.

Soviet General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev in a meeting with US President Ronald Reagan. Gorbachev sought to end the Cold War between the Soviet-led Warsaw Pact and the US-led capitalist West.

In 1985, Mikhail Gorbachev rose to power in the Soviet Union and began policies of radical political reform involving political liberalization, called Perestroika and Glasnost. Gorbachev's policies were designed at dismantling authoritarian elements of the state that were developed by Stalin, while aiming for a return to a supposed ideal Leninist state that retained single-party structure while allowing the democratic election of competing candidates within the Communist Party for political office. Gorbachev also aimed to seek detente with the West and end the Cold War that was no longer economically sustainable to be pursued by the Soviet Union. The Soviet Union and the United States under US President George H. W. Bush joined in pushing for the dismantlement of apartheid and oversaw the dismantlement of South African colonial rule over Namibia.

Meanwhile the eastern European communist states politically deteriorated in response to the success of the Polish Solidarity movement and the possibility of Gorbachev-style political liberalization. In 1989, revolts across Eastern Europe and China against Marxist-Leninist regimes. In China, the PRC refused to negotiate with student protestors resulting in the Tianamen Square attacks that stopped the revolts by force. The revolts culminated with the revolt in East Germany against the Stalinist regime of Erich Honecker and demands for the Berlin Wall to be torn down. The event in East Germany developed into a popular mass revolt with sections of the Berlin Wall being torn down and East and West Berliners uniting. Gorbachev's refusal to use Soviet forces based in East Germany to suppress the revolt was seen as a sign that the Cold War had ended. Honecker was pressured to resign from office and the new government committed itself to reunification with West Germany. The Stalinist regime of Nicolae Ceaușescu in Romania was forcefully overthrown in 1989 and Ceaușescu was executed. The other Warsaw Pact regimes fell in 1989 with the exception of the Socialist People's Republic of Albania that continued until 1992.

Unrest and eventual collapse of communism also occurred in Yugoslavia, though for different reasons than those of the Warsaw Pact. The death of Tito in 1980 and the subsequent vacuum of strong leadership allowed the rise of rival ethnic nationalism in the multinational country. The first leader to exploit such nationalism for political purposes was communist official Slobodan Milošević who used it to seize power as President of Serbia, and demanded concessions to Serbia and Serbs by the other republics in the Yugoslav federation. This resulted in a surge of Slovene and Croat nationalism in response and the collapse of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia in 1990, the victory of nationalists in multiparty elections in most of Yugoslavia's constituent republics, and eventually civil war between the various nationalities beginning in 1991. The SFRY was dissolved in 1992.

The Soviet Union itself collapsed between 1990 and 1991, with a rise of secessionist nationalism and a political power dispute between Gorbachev and the new non-communist leader of the Russian Federation, Boris Yeltsin. With the Soviet Union collapsing, Gorbachev prepared the country to become a loose non-communist federation of independent states called the Commonwealth of Independent States. Hardline communist leaders in the military reacted to Gorbachev's policies with the August Coup of 1991 in which hardline communist military leaders overthrew Gorbachev and seized control of the government. This regime only lasted briefly as widespread popular opposition erupted in street protests and refused to submit. Gorbachev was restored to power, but the various Soviet republics were now set for independence. On December 25, 1991, Gorbachev officially announced the dissolution of the Soviet Union, ending the existence of the world's first communist-led state.

Modern-day Marxism-Leninism and post-communist regimes (1992–present)

Since the fall of the Eastern European communist regimes, the Soviet Union, and a variety of African communist regimes, only a few remained by 1993, including: the People's Republic of China, Cuba, Vietnam, Laos, Angola, Mozambique, and Zimbabwe. Most communist parties outside those in power have faired poorly in elections. However the Communist Party of the Russian Federation has remained a significant political force. A variety of post-communist regimes whose government and cabinet members were formerly associated with Marxism–Leninism, existed in a number of countries. Post-communist regimes from 1991 to present have held power in Albania, Belarus, Croatia, Hungary, Kazakhstan, the Republic of Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia, and Slovenia.

The various post-communist regimes formed in the 1990s and 2000s, have held various positions, with no single unified position. In Belarus, Alexander Lukashenko had the country maintain much of its Marxist-Leninist command economy structure. In Slovenia, the formerly communist President Milan Kučan allowed substantial economic and political liberalization in the country, transforming the country into a capitalist market economy. In Serbia, the formerly communist President Slobodan Milošević and his Socialist Party of Serbia allowed multiparty democracy and some political and economic liberalization, however former communist officials and state authority in a number of sectors remained while utilizing nationalism to maintain popularity and substantial opposition to the regime was repressed until his overthrow in 2000. Milosevic's wife Mirjana Marković established a federal political party, the Yugoslav Left in 1994 in the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia that held substantial influence in the country that contained Marxist-Leninist ideology and official ties with the Communist Party of China, the Communist Party of Cuba, and the Workers' Party of Korea.

In Africa, many of the Marxist-Leninist regimes were dismantled in the 1990s. Only Zimbabwe maintained Marxism–Leninism though it too has been challenged with the multiparty elections in 2008 and a powersharing agreement between President Mugabe and his opponent, Prime Minsiter Morgan Tsvangirai.

In Asia, a number of Marxist-Leninist regimes and powerful movements continue to exist. The People's Republic of China has continued the agenda of Deng's reforms by initiating significant privatization of the economy. However no corresponding political liberalization has occurred as happened in eastern European countries. North Korean leader Kim Il-Sung died in 1994 and was replaced by his son, Kim Jong-il who initially pursued a policy of detente with South Korea and the West in exchange for economic support from the West. However talks broke down and the initiative failed. The Naxalite-Maoist insurgency has continued between the governments of India and Bangladesh against various Marxist-Leninist movements, unabated since the 1960s. Maoist rebels in Nepal engaged in a civil war from 1996 to 2006 that managed to topple the monarchy there and create a republic.

Alfonso Cano, who was,until his death, leader of the FARC, a Marxist-Leninist front in Columbia.

Alfonso Cano, who was,until his death, leader of the FARC, a Marxist-Leninist front in Columbia.

Cuba has allied itself with the popular radical socialist politics of Bolivarianism as supported by Hugo Chavez of Venezuela. Castro and Chavez formed a common front against American imperialism and capitalism. Unlike Marxism–Leninism, Bolivarianism accepts the existence of religion and multiparty democracy. Castro and Chavez have also been joined with the radical socialist agenda of Evo Morales of Bolivia. Marxist-Leninist leader Daniel Ortega returned to power in Nicaragua in 2007. The Marxist-Leninist paramilitary organization the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) is a significant political force in Colombia and has received political support from Chavez. In the ongoing internal conflict in Peru, the Peruvian government faces opposition from Marxist-Leninist and Maoist militants.

See also

- Fundamentals of Marxism–Leninism

References

- ^ a b Michael Albert, Robin Hahnel. Socialism today and tomorrow. Boston, Massachusetts, USA: South End Press, 1981. Pp. 24-25.

- ^ Silvo Pons (ed.) and Robert Service (ed.). A Dictionary of 20th Century Communism. Princeton, New Jersey, USA; Oxfordshire, England, UK: Princeton University Press. Pp. 526.

- ^ a b c d Ian Adams. Political ideology today. Manchester England, UK: Manchester University Press, 1993. Pp. 201.

- ^ a b Alexander Shtromas, Robert K. Faulkner, Daniel J. Mahoney. Totalitarianism and the prospects for world order: closing the door on the twentieth century. Oxford, England, UK; Lanham, Maryland, USA: Lexington Books, 2003. Pp. 18.

- ^ Michael Albert, Robin Hahnel. Socialism today and tomorrow. Boston, Massachusetts, USA: South End Press, 1981. Pp. 25.

- ^ a b Charles F. Andrain. Comparative political systems: policy performance and social change. Armonk, New York, USA: M. E. Sharpe, Inc., 1994. Pp. 140.

- ^ a b János Kornai. From socialism to capitalism: eight essays. Budapest, Hungary: Central European University Press, 2008. Pp. 54.

- ^ Г. Лисичкин (G. Lisichkin), Мифы и реальность, Новый мир (Novy Mir), 1989, № 3, p. 59 (Russian)

- ^ Александр Бутенко (Aleksandr Butenko), Социализм сегодня: опыт и новая теория// Журнал Альтернативы, №1, 1996, pp. 3–4 (Russian)

- ^ Александр Бутенко (Aleksandr Butenko), Социализм сегодня: опыт и новая теория// Журнал Альтернативы, №1, 1996, pp. 2–22 (Russian)

- ^ Лев Троцкий (Lev Trotsky), Сталинская школа фальсификаций, М. 1990, pp. 7–8 (Russian)

- ^ М. Б. Митин (M. B. Mitin). "Марксизм-ленинизм". Яндекс. http://slovari.yandex.ru/dict/bse/article/00045/73200.htm?text=%D0%BC%D0%B0%D1%80%D0%BA%D1%81%D0%B8%D0%B7%D0%BC-%D0%BB%D0%B5%D0%BD%D0%B8%D0%BD%D0%B8%D0%B7%D0%BC. Retrieved 2010-10-18. (Russian)[dead link]

- ^ a b c d e Silvo Pons (ed.) and Robert Service (ed.). A Dictionary of 20th Century Communism. Princeton, New Jersey, USA; Oxfordshire, England, UK: Princeton University Press. Pp. 721.

- ^ a b c d e f g Silvo Pons (ed.) and Robert Service (ed.). A Dictionary of 20th Century Communism. Princeton, New Jersey, USA; Oxfordshire, England, UK: Princeton University Press. Pp. 722.

- ^ Silvo Pons (ed.) and Robert Service (ed.). A Dictionary of 20th Century Communism. Princeton, New Jersey, USA; Oxfordshire, England, UK: Princeton University Press. Pp. 723.

- ^ Silvo Pons (ed.) and Robert Service (ed.). A Dictionary of 20th Century Communism. Princeton, New Jersey, USA; Oxfordshire, England, UK: Princeton University Press. Pp. 318.

- ^ a b Silvo Pons (ed.) and Robert Service (ed.). A Dictionary of 20th Century Communism. Princeton, New Jersey, USA; Oxfordshire, England, UK: Princeton University Press. Pp. 317.

- ^ a b Silvo Pons (ed.) and Robert Service (ed.). A Dictionary of 20th Century Communism. Princeton, New Jersey, USA; Oxfordshire, England, UK: Princeton University Press. Pp. 319.

- ^ Silvo Pons (ed.) and Robert Service (ed.). A Dictionary of 20th Century Communism. Princeton, New Jersey, USA; Oxfordshire, England, UK: Princeton University Press. Pp. 722-723.

- ^ Silvo Pons (ed.) and Robert Service (ed.). A Dictionary of 20th Century Communism. Princeton, New Jersey, USA; Oxfordshire, England, UK: Princeton University Press. Pp. 580.

- ^ Silvo Pons (ed.) and Robert Service (ed.). A Dictionary of 20th Century Communism. Princeton, New Jersey, USA; Oxfordshire, England, UK: Princeton University Press. Pp. 854-856.

- ^ Silvo Pons (ed.) and Robert Service (ed.). A Dictionary of 20th Century Communism. Princeton, New Jersey, USA; Oxfordshire, England, UK: Princeton University Press. Pp. 854.

- ^ Silvo Pons (ed.) and Robert Service (ed.). A Dictionary of 20th Century Communism. Princeton, New Jersey, USA; Oxfordshire, England, UK: Princeton University Press. Pp. 855.

- ^ Silvo Pons (ed.) and Robert Service (ed.). A Dictionary of 20th Century Communism. Princeton, New Jersey, USA; Oxfordshire, England, UK: Princeton University Press. Pp. 856.

- ^ Silvo Pons (ed.) and Robert Service (ed.). A Dictionary of 20th Century Communism. Princeton, New Jersey, USA; Oxfordshire, England, UK: Princeton University Press. Pp. 250.

- ^ a b Silvo Pons (ed.) and Robert Service (ed.). A Dictionary of 20th Century Communism. Princeton, New Jersey, USA; Oxfordshire, England, UK: Princeton University Press. Pp. 250-251.

- ^ a b Silvo Pons (ed.) and Robert Service (ed.). A Dictionary of 20th Century Communism. Princeton, New Jersey, USA; Oxfordshire, England, UK: Princeton University Press. Pp. 251.

- ^ a b Silvo Pons (ed.) and Robert Service (ed.). A Dictionary of 20th Century Communism. Princeton, New Jersey, USA; Oxfordshire, England, UK: Princeton University Press. Pp. 251-252.

- ^ a b Silvo Pons (ed.) and Robert Service (ed.). A Dictionary of 20th Century Communism. Princeton, New Jersey, USA; Oxfordshire, England, UK: Princeton University Press. Pp. 581.

- ^ Silvo Pons (ed.) and Robert Service (ed.). A Dictionary of 20th Century Communism. Princeton, New Jersey, USA; Oxfordshire, England, UK: Princeton University Press. Pp. 581-582.

- ^ a b Silvo Pons (ed.) and Robert Service (ed.). A Dictionary of 20th Century Communism. Princeton, New Jersey, USA; Oxfordshire, England, UK: Princeton University Press. Pp. 253.

- ^ Silvo Pons (ed.) and Robert Service (ed.). A Dictionary of 20th Century Communism. Princeton, New Jersey, USA; Oxfordshire, England, UK: Princeton University Press. Pp. 254.

- ^ a b c Silvo Pons (ed.) and Robert Service (ed.). A Dictionary of 20th Century Communism. Princeton, New Jersey, USA; Oxfordshire, England, UK: Princeton University Press. Pp. 138.

- ^ a b c Silvo Pons (ed.) and Robert Service (ed.). A Dictionary of 20th Century Communism. Princeton, New Jersey, USA; Oxfordshire, England, UK: Princeton University Press. Pp. 139.

- ^ a b c d e f Silvo Pons (ed.) and Robert Service (ed.). A Dictionary of 20th Century Communism. Princeton, New Jersey, USA; Oxfordshire, England, UK: Princeton University Press. Pp. 140.

- ^ a b Silvo Pons (ed.) and Robert Service (ed.). A Dictionary of 20th Century Communism. Princeton, New Jersey, USA; Oxfordshire, England, UK: Princeton University Press. Pp. 467.

- ^ a b c Silvo Pons (ed.) and Robert Service (ed.). A Dictionary of 20th Century Communism. Princeton, New Jersey, USA; Oxfordshire, England, UK: Princeton University Press. Pp. 731.

- ^ Silvo Pons (ed.) and Robert Service (ed.). A Dictionary of 20th Century Communism. Princeton, New Jersey, USA; Oxfordshire, England, UK: Princeton University Press. Pp. 732.

- ^ a b c d Silvo Pons (ed.) and Robert Service (ed.). A Dictionary of 20th Century Communism. Princeton, New Jersey, USA; Oxfordshire, England, UK: Princeton University Press. Pp. 446.

- ^ Silvo Pons (ed.) and Robert Service (ed.). A Dictionary of 20th Century Communism. Princeton, New Jersey, USA; Oxfordshire, England, UK: Princeton University Press. Pp. 446-447.

- ^ a b Silvo Pons (ed.) and Robert Service (ed.). A Dictionary of 20th Century Communism. Princeton, New Jersey, USA; Oxfordshire, England, UK: Princeton University Press. Pp. 447.

- ^ Silvo Pons (ed.) and Robert Service (ed.). A Dictionary of 20th Century Communism. Princeton, New Jersey, USA; Oxfordshire, England, UK: Princeton University Press. Pp. 448.

- ^ a b c d e f Silvo Pons (ed.) and Robert Service (ed.). A Dictionary of 20th Century Communism. Princeton, New Jersey, USA; Oxfordshire, England, UK: Princeton University Press. Pp. 306.

- ^ a b c Silvo Pons (ed.) and Robert Service (ed.). A Dictionary of 20th Century Communism. Princeton, New Jersey, USA; Oxfordshire, England, UK: Princeton University Press. Pp. 258.

- ^ a b c d Silvo Pons (ed.) and Robert Service (ed.). A Dictionary of 20th Century Communism. Princeton, New Jersey, USA; Oxfordshire, England, UK: Princeton University Press. Pp. 259.

- ^ Silvo Pons (ed.) and Robert Service (ed.). A Dictionary of 20th Century Communism. Princeton, New Jersey, USA; Oxfordshire, England, UK: Princeton University Press. Pp. 260.

- ^ Silvo Pons (ed.) and Robert Service (ed.). A Dictionary of 20th Century Communism. Princeton, New Jersey, USA; Oxfordshire, England, UK: Princeton University Press. Pp. 326.

- ^ T. B. Bottomore. A Dictionary of Marxist thought. Malden, Massaschussetts, USA; Oxford, England, UK; Melbourne, Victoria, Australia; Berlin, Germany: Wiley-Blackwell, 1991. Pp. 53-54.

- ^ a b c d e T. B. Bottomore. A Dictionary of Marxist thought. Malden, Massaschussetts, USA; Oxford, England, UK; Melbourne, Victoria, Australia; Berlin, Germany: Wiley-Blackwell, 1991. Pp. 54.

- ^ a b c T. B. Bottomore. A Dictionary of Marxist thought. Malden, Massaschussetts, USA; Oxford, England, UK; Melbourne, Victoria, Australia; Berlin, Germany: Wiley-Blackwell, 1991. Pp. 259.

- ^ Adam Bruno Ulam. The Bolsheviks: the intellectual and political history of the triumph of communism in Russia. Harvard University Press, 1965, 1998. Pp. 257.

- ^ Adam Bruno Ulam. The Bolsheviks: the intellectual and political history of the triumph of communism in Russia. Harvard University Press, 1965, 1998. Pp. 204.

- ^ a b Adam Bruno Ulam. The Bolsheviks: the intellectual and political history of the triumph of communism in Russia. Harvard University Press, 1965, 1998. Pp. 207.

- ^ Adam Bruno Ulam. The Bolsheviks: the intellectual and political history of the triumph of communism in Russia. Harvard University Press, 1965, 1998. Pp. 269.

- ^ a b c Adam Bruno Ulam. The Bolsheviks: the intellectual and political history of the triumph of communism in Russia. Harvard University Press, 1965, 1998. Pp. 270.

- ^ a b T. B. Bottomore. A Dictionary of Marxist thought. Malden, Massaschussetts, USA; Oxford, England, UK; Melbourne, Victoria, Australia; Berlin, Germany: Wiley-Blackwell, 1991. Pp. 98.

- ^ Adam Bruno Ulam. The Bolsheviks: the intellectual and political history of the triumph of communism in Russia. Harvard University Press, 1965, 1998. Pp. 282-283.

- ^ Adam Bruno Ulam. The Bolsheviks: the intellectual and political history of the triumph of communism in Russia. Harvard University Press, 1965, 1998. Pp. 284.

- ^ a b Kevin Anderson. Lenin, Hegel, and Western Marxism: a critical study. Chicago, Illinois, USA: University of Illinois Press, 1995. Pp. 3.

- ^ Carl Cavanagh Hodge. Encyclopedia of the Age of Imperialism, 1800-1914, Volume 2. Westport, Connecticut, USA: Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc., 2008. Pp. 415.

- ^ Ian Frederick William Beckett. 1917: beyond the Western Front. Leiden, The Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV, 2009. Pp. 1.

- ^ Stephen J. Lee. European dictatorships, 1918-1945. 2nd edition. London, England, UK; New York, New York, USA: Routledge, 2000. Pp. 31.

- ^ a b c d Stephen J. Lee. European dictatorships, 1918-1945. 2nd edition. London, England, UK; New York, New York, USA: Routledge, 2000. Pp. 37.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Stephen J. Lee. European dictatorships, 1918-1945. 2nd edition. London, England, UK; New York, New York, USA: Routledge, 2000. Pp. 38.

- ^ Adam Bruno Ulam. The Bolsheviks: the intellectual and political history of the triumph of communism in Russia. Harvard University Press, 1965, 1998. Pp. 249.

- ^ a b Stephen J. Lee. European dictatorships, 1918-1945. 2nd edition. London, England, UK; New York, New York, USA: Routledge, 2000. Pp. 39.

- ^ a b Stephen J. Lee. European dictatorships, 1918-1945. 2nd edition. London, England, UK; New York, New York, USA: Routledge, 2000. Pp. 41.

- ^ a b Stephen J. Lee. European dictatorships, 1918-1945. 2nd edition. London, England, UK; New York, New York, USA: Routledge, 2000. Pp. 41-42.

- ^ a b c Stephen J. Lee. European dictatorships, 1918-1945. 2nd edition. London, England, UK; New York, New York, USA: Routledge, 2000. Pp. 42.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Stephen J. Lee. European dictatorships, 1918-1945. 2nd edition. London, England, UK; New York, New York, USA: Routledge, 2000. Pp. 43.

- ^ a b c d Stephen J. Lee. European dictatorships, 1918-1945. 2nd edition. London, England, UK; New York, New York, USA: Routledge, 2000. Pp. 47.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Stephen J. Lee. European dictatorships, 1918-1945. 2nd edition. London, England, UK; New York, New York, USA: Routledge, 2000. Pp. 49.

- ^ Stephen J. Lee. European dictatorships, 1918-1945. 2nd edition. London, England, UK; New York, New York, USA: Routledge, 2000. Pp. 60.

- ^ Stephen J. Lee. European dictatorships, 1918-1945. 2nd edition. London, England, UK; New York, New York, USA: Routledge, 2000. Pp. 53.

- ^ Stephen J. Lee. European dictatorships, 1918-1945. 2nd edition. London, England, UK; New York, New York, USA: Routledge, 2000. Pp. 60-61.

- ^ Timothy Snyder, Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin, p.53 (he states that this figure "must be substantially low, since many deaths were not recorded.")

- ^ Anatoliy Vlasyuk, Nationalism and Holodomor, p.53 (he states that this the absolute minimum killed, by looking at the population loss would be around 4.5 million, with 7.5 million being more likely, and 10 million also being possible.")

- ^ Stephen J. Lee. European dictatorships, 1918-1945. 2nd edition. London, England, UK; New York, New York, USA: Routledge, 2000. Pp. 59.

- ^ a b c d e Stephen J. Lee. European dictatorships, 1918-1945. 2nd edition. London, England, UK; New York, New York, USA: Routledge, 2000. Pp. 63.

- ^ a b Stephen J. Lee. European dictatorships, 1918-1945. 2nd edition. London, England, UK; New York, New York, USA: Routledge, 2000. Pp. 62.

- ^ Stephen J. Lee. European dictatorships, 1918-1945. 2nd edition. London, England, UK; New York, New York, USA: Routledge, 2000. Pp. 73.

- ^ a b c Stephen J. Lee. European dictatorships, 1918-1945. 2nd edition. London, England, UK; New York, New York, USA: Routledge, 2000. Pp. 74.

- ^ Stephen J. Lee. European dictatorships, 1918-1945. 2nd edition. London, England, UK; New York, New York, USA: Routledge, 2000. Pp. 74-75.

- ^ a b c Stephen J. Lee. European dictatorships, 1918-1945. 2nd edition. London, England, UK; New York, New York, USA: Routledge, 2000. Pp. 80.

- ^ a b Stephen J. Lee. European dictatorships, 1918-1945. 2nd edition. London, England, UK; New York, New York, USA: Routledge, 2000. Pp. 81.

External links

- Definition at marxists.org

- Fundamentals of Marxism–Leninism Soviet textbook explaining Marxism–Leninism

- Leninist Ebooks

- Alexander Spirkin. Fundamentals of Philosophy. Translated from Russian by Sergei Syrovatkin. Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1990.

- Spirkin's textbook offers a systematic exposition of the foundations of dialectical and historical materialism. The book was awarded a prize[which?] at a competition of textbooks for students of higher educational establishments.

Categories:- Communism

- Political philosophy by politician

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.