- Private spaceflight

-

This article is about non-governmental spaceflight. For paying space tourists, see Space tourism. For general commercial use of space, see Commercialization of space.

Private spaceflight is flight above 100 km (62 mi) Earth altitude conducted by and paid for by an entity other than a government. In the early decades of the Space Age, the government space agencies of the Soviet Union and United States pioneered space technology augmented by collaboration with affiliated design bureaus in the USSR and private companies in the US. The European Space Agency was formed in 1975, largely following the same model of space technology development. Later on, large defense contractors began to develop and operate space launch systems, derived from government rockets and commercial satellites. Private spaceflight in Earth orbit includes communications satellites, satellite television, satellite radio, astronaut transport and sub-orbital and orbital space tourism. Recently, entrepreneurs have begun designing and deploying competitive space systems to the national-monopoly governmental systems of the early decades of the space age. Successes to date include flying suborbital spaceplanes and launching lightweight orbital rockets. Planned private spaceflights beyond Earth orbit include solar sailing prototypes,[citation needed] deep space burial[citation needed] and personal spaceflights around the Moon.[citation needed] Two private orbital habitat prototypes are already in Earth orbit, with larger versions to follow.[1]

Contents

History of commercial space transportation

During the early years of spaceflight, since the mid-twentieth century, only nation states had the resources to develop and fly spacecraft. Spaceflight was thus the monopoly province of a small group of national governments.

Both the U.S. space program and Soviet space program were operated using mainly military pilots as astronauts. During this period, no commercial space launches were available to private operators, and no private organization was able to offer space launches. Eventually, private organizations were able to both offer and purchase space launches, thus beginning the period of private spaceflight.

The first phase of private space operation was the launch of the first commercial communications satellites. The U.S. Communications Satellite Act of 1962 opened the way to commercial consortia owning and operating their own satellites, although these were still launched on state-owned launch vehicles.

History of full private space transportation includes early efforts by Germany OTRAG company in the 20th century and numerous modern projects of orbital and suborbital launch systems in the 21st century. Last ones counts the manned programs also - most famous and important of them are suborbital flights of Virgin Galactic and orbital flights of SpaceX and other COTS participants.

European state-sponsorship

On March 26, 1980, the European Space Agency created Arianespace, the world's first commercial space transportation company. Arianespace produces, operates and markets the Ariane launcher family. By 1995 Arianespace lofted its 100th satellite and by 1997 the Ariane rocket had its 100th launch.[2] Arianespace's 23 shareholders represent scientific, technical, financial and political entities from 10 different European countries.[3]

Private European

American deregulation

From the beginning of the Shuttle program until the Challenger disaster in 1986, it was the policy of the United States that NASA be the public-sector provider of U.S. launch capacity to the world market.[4] Initially NASA subsidized satellite launches with the intention of eventually pricing Shuttle service for the commercial market at long-run marginal cost.[citation needed]

On October 30, 1984, United States President Ronald Reagan signed into law the Commercial Space Launch Act.[5] This enabled an American industry of private operators of expendable launch systems. Prior to the signing of this law, all commercial satellite launches in the United States were restricted by Federal regulation to NASA's Space Shuttle.

On November 5, 1990, United States President George H. W. Bush signed into law the Launch Services Purchase Act.[6] The Act, in a complete reversal of the earlier Space Shuttle monopoly, ordered NASA to purchase launch services for its primary payloads from commercial providers whenever such services are required in the course of its activities.

Commercial launches outnumbered government launches at the Eastern Test Range in 1997.[7]

Russian privatization

In 1992, Resurs-500 capsule containing gifts was launched from Plesetsk Cosmodrome in what was a private spaceflight called Europe-America 500. The flight was conceived by the Russian Foundation for Social Inventions and Photon, a Russian rocket-building company, to increase trade between Russia and USA, and promote use of technology once reserved only for military forces. Money for the launch was raised from a collection of Russian companies. The capsule parachuted into the Pacific Ocean and was brought to Seattle by a Russian missile-tracking ship.

The Russian government sold part of its stake in RSC Energia to private investors in 1994. Energia together with Khrunichev constituted most of the Russian manned space program. In 1997, the Russian government sold off enough of its share to lose the majority position.

American subsidization

In 1996 the United States government selected Lockheed Martin and Boeing to each develop Evolved Expendable Launch Vehicles (EELV) to compete for launch contracts and provide assured access to space. The government's acquisition strategy relied on the strong commercial viability of both vehicles to lower unit costs. This anticipated market demand did not materialize, but both the Delta IV and Atlas V EELVs remain in active service.

Launch alliances

Since 1995 Khrunichev's Proton rocket is marketed through International Launch Services while the Soyuz rocket is marketed via Starsem. Energia builds the Soyuz rocket and owns part of the Sea Launch project which flies the Ukrainian Zenit rocket.

In 2003 Arianespace joined with Boeing Launch Services and Mitsubishi Heavy Industries to create the Launch Services Alliance. In 2005, continued weak commercial demand for EELV launches drove Lockheed Martin and Boeing to propose a joint venture called the United Launch Alliance to service the United States government launch market.[8]

Human spaceflight privatization

On February 1, 2010 United States President Barack Obama proposed in a speech that NASA exit the business of flying astronauts from Earth to orbit. The proposal acted on the findings of the 2009 Augustine Commission and built on the success of the Commercial Resupply Services that outsourced American cargo delivery to the International Space Station.[9]

Today many commercial space transportation companies offer launch services to satellite companies and government space organizations around the world. In 2005 there were 18 total commercial launches and 37 non-commercial launches.[10] Russia flew 44% of commercial orbital launches, while Europe had 28% and the United States had 6%.

Private spaceflight companies

Commercial launchers

The space transport business serves primarily national government and large commercial customer segments. Launches of government payloads, including military, civilian and scientific satellites, is the largest market segment at nearly $100 billion a year. This segment is dominated by domestic favorites such as the United Launch Alliance for U.S. government payloads and Arianespace for European satellites. The commercial payload segment, valued at under $3 billion a year, is dominated by Arianespace, with over 50% of the market segment,[11] followed by Russian launchers. See a complete list of launch systems.

Commercial Orbital Transportation Services

On January 18, 2006 NASA announced an opportunity for commercial providers to demonstrate orbital transportation services.[12] NASA plans to spend $500 million through 2010 to finance development of private sector capability to transport payloads to the International Space Station (ISS). This is more challenging than extant commercial space transportation because it requires precision orbit insertion, rendezvous and possibly docking with another spacecraft. The commercial vendors will compete in specific service areas.[13] NASA Administrator Michael D. Griffin has stated that without affordable commercial orbital transportation services (COTS), the agency will not have enough funds remaining to achieve the objectives of the Vision for Space Exploration.

In August 2006, NASA announced that two fledgling aerospace companies, SpaceX and Rocketplane Kistler, had been awarded $278m and $207m, respectively, under the COTS program.[14] NASA anticipates that COTS services to ISS will be necessary through at least 2015. The NASA Administrator has suggested that space transportation services procurement may be expanded to orbital fuel depots and lunar surface deliveries should the first phase of COTS prove successful.[15]

After it transpired that Rocketplane Kistler was failing to meet its deadlines, the NASA terminated their contract in August 2008, after only $32m had been spent. Several months later, in December 2008, NASA announced that they have awarded the remaining $170m to the trusted Orbital Sciences Corporation to develop resupply services to the ISS.[16]

Commercial Space Station

Main article: Bigelow Commercial Space StationBigelow Aerospace is developing the Next-Generation Commercial Space Station, a private orbital space complex. The space station will be constructed of both Sundancer and BA 330 expandable spacecraft modules as well as a central docking node, propulsion, solar arrays, and attached crew capsules. As of July 2010[update], initial launch of space station components is planned for 2014, with portions of the station projected to be available for leased use as early as 2015.[17]

Emerging personal spaceflight

Before 2004 no privately operated manned spaceflight had ever occurred. The only private individuals to journey to space went as space tourists in the Space Shuttle or on Russian Soyuz flights to Mir or the International Space Station.

All private individuals who flew to space before Dennis Tito's self-financed International Space Station visit in 2001 had been sponsored by their home governments. Those trips include US Congressman Bill Nelson's January 1986 flight on the Space Shuttle Columbia and Japanese television reporter Toyohiro Akiyama's 1990 flight to the Mir Space Station.

The Ansari X PRIZE was intended to stimulate private investment in the development of spaceflight technologies. The June 21, 2004 test flight of SpaceShipOne, a contender for the X PRIZE, was the first human spaceflight in a privately developed and operated vehicle.

On September 27, 2004, following the success of SpaceShipOne, Richard Branson, owner of Virgin and Burt Rutan, SpaceShipOne's designer, announced that Virgin Galactic had licensed the craft's technology, and were planning commercial space flights in 2.5 to 3 years. A fleet of five craft (SpaceShipTwo, launched from the WhiteKnightTwo carrier airplane) is to be constructed, and flights will be offered at around $200,000 each, although Branson has said he plans to use this money to make flights more affordable in the long term.[dated info]

XCOR Aerospace also plans to initiate a suborbital commercial spaceflight service with the Lynx rocketplane in 2012 through a partnership with RocketShip Tours. First test flights are planned for 2010.[citation needed]

In December 2004, United States President George W. Bush signed in to law the Commercial Space Launch Amendments Act.[18] The Act resolved the regulatory ambiguity surrounding private spaceflights and is designed to promote the development of the emerging U.S. commercial human space flight industry.

On July 12, 2006, Bigelow Aerospace launched the Genesis I, a subscale pathfinder of an orbital space station module. Genesis II was launched on June 28, 2007, and there are plans for additional prototypes to be launched in preparation for the production model BA 330 spacecraft.[dated info]

On September 28, 2006, Jim Benson, SpaceDev founder, announced he was founding Benson Space Company with the intention of being first to market with the safest and lowest cost suborbital personal spaceflight launches, using the vertical takeoff and horizontal landing Dream Chaser vehicle based on the NASA HL-20 Personnel Launch System vehicle.[dated info]

Failed spaceflight ventures

After earlier first effort of OTRAG, in the 1990s the projection of a significant demand for communications satellite launches attracted the development of a number of commercial space launch providers. The launch demand largely vanished when some of the largest satellite constellations, such as 288 satellite Teledesic network, were never built. The historic tendency of NASA to compete against the private sector and the Department of Defense's preference for the traditional military industrial complex has discouraged many new space launch ventures.[citation needed]

VentureStar

In 1996 NASA selected Lockheed Martin Skunk Works to build the X-33 VentureStar prototype for a single stage to orbit (SSTO) reusable launch vehicle. In 1999, the subscale X-33 prototype's composite liquid hydrogen fuel tank failed during testing. At project termination on March 31, 2001, NASA had funded $912 million of this wedge shaped spacecraft while Lockheed Martin financed $357 million of it.[19] The VentureStar was to have been a full-scale commercial space transport operated by Lockheed Martin.

Beal Aerospace

In 1997 Beal Aerospace proposed the BA-2, a low-cost heavy-lift commercial launch vehicle. On March 4, 2000, the BA-2 project tested the largest liquid rocket engine built since the Saturn V.[20] In October 2000, Beal Aerospace ceased operations citing a decision by NASA and the Department of Defense to commit themselves to the development of the competing government-financed EELV program.[21]

Rotary Rocket

In 1998 Rotary Rocket proposed the Roton, a Single Stage to Orbit (SSTO) piloted Vertical Take-off and Landing (VTOL) space transport.[22] A full scale Roton Atmospheric Test Vehicle flew three times in 1999. After spending tens of millions of dollars in development the Roton failed to secure launch contracts and Rotary Rocket ceased operations in 2001.

Future plans

Many have speculated on where private spaceflight may go in the near future. Numerous projects of orbital and suborbital launch systems for satellites and manned flights exist. Some orbital manned missions would be state-sponsored like most COTS participants. (that develop their own launch systems). Another possibility is for paid suborbital tourism on craft like those from Virgin Galactic, Space Adventures, XCOR Aerospace, RocketShip Tours, ARCASPACE, PlanetSpace-Canadian Arrow, British Starchaser Industries or non-commercial like Copenhagen Suborbitals. Additionally, suborbital spacecraft have applications for faster intercontinental package delivery and passenger flight.

Private orbital spaceflight, space stations

SpaceX's Falcon 9 rocket, first launched in 2010 with no passengers,[23] is designed to be subsequently man-rated. The Atlas V is also a contender for being man-rated.

Plans and a full-scale prototype for the SpaceX Dragon, a manned capsule carrying up to 7 passengers, were announced on March 6, 2006.[24][dated info]

In December 2010, SpaceX launched the second Falcon 9 and the first operational Dragon spacecraft. The mission was deemed fully successful, marking the first launch, atmospheric reentry and recovery of a spacecraft by a private company. Subsequent COTS missions include increasingly complex orbital tasks, culminating in Dragon docking to the ISS.

An early flight of the Falcon 9 is planned to carry Sundancer, the prototype expandable and habitable space module (based on the former NASA TransHab design) constructed by Bigelow Aerospace. Bigelow Aerospace expects modules like Sundancer and the larger BA 330 to be used for activities like microgravity research, space manufacturing, and space tourism (with modules serving as orbital hotels). To promote private manned launch efforts, Bigelow offered the US$50 million America's Space Prize for the first US-based privately funded team to launch a manned reusable spacecraft to orbit on or before January 10, 2010, though no company was able to meet this deadline.

Excalibur Almaz plans to launch a modernized TKS Spacecraft (for Almaz space station), for tourism and other uses. It will feature the largest window ever on a spacecraft. The British Government has recently partnered with the ESA to promote a possibly commercial single-stage to orbit spaceplane concept called Skylon.[25] This design was pioneered by the privately held Reaction Engines Limited,[26][27] a company founded by Alan Bond after HOTOL was canceled.[28]

On-orbit propellant depots

Main article: Propellant depotIn a presentation given November 15, 2005, to the 52nd Annual Conference of the American Astronautical Society, NASA Administrator Michael D. Griffin suggested that establishing an on-orbit propellant depot is, "Exactly the type of enterprise which should be left to industry and to the marketplace."[29] At the Space Technology and Applications International Forum in 2007, Dallas Bienhoff of Boeing made a presentation detailing the benefits of propellant depots.[30]

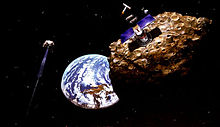

Asteroid mining

Some have speculated on the profitability of mining metal from asteroids. According to some estimates, a one kilometer-diameter asteroid would contain 30 million tons of nickel, 1.5 million tons of metal cobalt and 7,500 tons of platinum; the platinum alone would have a value of more than $150 billion at current prices.[31]

Energy from space

Future energy development may use energy sources in space and on other planets. Examples include Helium-3 extraction from the Moon, and solar power satellite systems. See space manufacturing for more on extraterrestrial economic development.

Space elevators

A space elevator system is a possible launch system, currently under investigation by at least one private venture.[32] There are concerns over cost, general feasibility and some political issues. On the plus side the potential to scale the system to accommodate traffic would (in theory) be greater than some other alternatives. Some factions contend that a space elevator — if successful — would not supplant existing launch solutions but complement them.

See also

- Commercial Spaceflight Federation

- Space Frontier Foundation

- L5 Society

- SpaceX

- Orbital Sciences Corporation

- OTRAG

- Rocketplane Kistler

- Beal Aerospace

- Rotary Rocket

- Heinlein Prize for Advances in Space Commercialization

- Masten Space Systems

- Open Source Aerospace Project

- X Prize Foundation

- Virgin Galactic

- Space Adventures

- Blue Origin

- XCOR Aerospace

- RocketShip Tours

- ARCASPACE

- PlanetSpace

- Starchaser Industries

- Armadillo Aerospace

- Copenhagen Suborbitals

Manned Spacecraft

- SpaceX Dragon - Orbital Capsule

- Boeing CST-100 - Orbital Capsule

- Excalibur Almaz - Orbital Capsule

- PlanetSpace Silver Dart - Orbital Spaceplane

- SpaceDev Dream Chaser - Orbital Spaceplane

- Reaction Engines Skylon - Single-Stage-To-Orbit Spaceplane

- Scaled Composites SpaceShipOne - Suborbital Spaceplane

- Scaled Composites/Virgin Galactic SpaceShipTwo - Suborbital Spaceplane

- XCOR Lynx - Suborbital Spaceplane

- ARCASPACE Stabilo and ORIZONT - Suborbital Capsule and Spaceplane

- Blue Origin New Shepard - Suborbital Capsule

- PlanetSpace Canadian Arrow - Suborbital Capsule

- Armadillo Aerospace Black Armadillo - Suborbital Capsule

- Starchaser Industries Thunderbird and Thunderstar - Suborbital Capsule

- Copenhagen Suborbitals HEAT1X and Tycho Brahe - Suborbital Capsule

Unmanned Spacecraft

References

- ^ "Special Announcement". bigelowaerospace.com. http://www.bigelowaerospace.com/news/?Special_Announcement. Retrieved 2008-04-01.

- ^ "Milestones". Arianespace.com. Archived from the original on 2008-01-13. http://web.archive.org/web/20080113040347/http://www.arianespace.com/site/about/milestones_sub_index.html. Retrieved 2008-02-14.

- ^ "Arianespace shareholders represent scientific, technical, financial and political entities from 10 different European countries". Arianespace.com. Archived from the original on 2008-02-06. http://web.archive.org/web/20080206075437/http://www.arianespace.com/site/about/shareholders_sub_index.html. Retrieved 2008-02-14.

- ^ "Setting Space Transportation Policy for the 1990s" (PDF). cbo.gov. http://www.cbo.gov/ftpdocs/59xx/doc5935/doc24c-Entire.pdf. Retrieved 2008-02-14.

- ^ "Statement on Signing the Commercial Space Launch Act". reagan.utexas.edu. http://www.reagan.utexas.edu/archives/speeches/1984/103084i.htm. Retrieved 2008-02-14.

- ^ "$ 2465d. Requirement of US Federal government to procure commercial launch services". space-frontier.org. http://www.space-frontier.org/commercialspace/lspalaw.txt. Retrieved 2008-02-14.

- ^ "Streamlining Space Launch Range Safety - Executive Summary". National Academy of Sciences. http://books.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=9790&page=1. Retrieved 2008-02-13.

- ^ "Boeing, Lockheed Martin to Form Launch Services Joint Venture". spaceref.com. http://www.spaceref.com/news/viewpr.html?pid=16790. Retrieved 2008-02-13.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (2010-02-02). "Obama Calls for End to NASA’s Moon Program" (PDF). nytimes.com. http://www.nytimes.com/2010/02/02/science/space/02nasa.html. Retrieved 2010-02-01.

- ^ "Commercial Space Transportation: 2005 Year In Review" (PDF). faa.gov. http://www.faa.gov/about/office_org/headquarters_offices/ast/media/2005_YIR_FAA_AST_0206.pdf. Retrieved 2008-02-13.

- ^ "Changing Trajectory: French Firms Vaults Ahead in Civilian Rocket Market". The Wall Street Journal (Dow Jones & Company, Inc.): A1. June 25, 2007.

- ^ "NASA Seeks Proposals for Crew and Cargo Transportation to Orbit". spaceref.com. http://www.spaceref.com/news/viewpr.html?pid=18791. Retrieved 2008-02-11.

- ^ "GUIDANCE_FOR_THE_PREPARATION_AND_SUBMISSION_OF_UNSOLICITED_PROPOSALS". nasa.gov. http://ec.msfc.nasa.gov/hq/library/unSol-Prop.html. Retrieved 2008-02-13.[dead link]

- ^ "NASA Invests in Private Sector Space Flight with SpaceX, Rocketplane-Kistler". nasa.gov. http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/exploration/news/COTS_selection.html. Retrieved 2008-02-14.

- ^ "Human_Space_Flight_Transition_Plan" (PDF). nasa.gov. Archived from the original on 2008-02-27. http://web.archive.org/web/20080227051121/http://spaceoperations.nasa.gov/tran_plan.pdf. Retrieved 2008-02-14.

- ^ "NASA Awards Space Station Commercial Resupply Services Contracts". nasa.gov. http://www.nasa.gov/home/hqnews/2008/dec/HQ_C08-069_ISS_Resupply.html. Retrieved 2008-12-24.

- ^ Bigelow Aerospace — Next-Generation Commercial Space Stations: Orbital Complex Construction, Bigelow Aerospace, accessed 2010-07-15.

- ^ "House Approves H.R. 3752, The Commercial Space Launch Amendments Act of 2004". spaceref.com. http://www.spaceref.com/news/viewpr.html?pid=13774. Retrieved 2008-02-14.

- ^ "NASA Reaches Milestone in Space Launch Initiative Program". nasa.gov. http://www.hq.nasa.gov/office/pao/History/x-33/01-31.htm. Retrieved 2008-02-14.

- ^ "Beal BA-2". astronautix.com. http://www.astronautix.com/lvs/bealba2.htm. Retrieved 2008-02-14.

- ^ "Beal Aerospace regrets to announce that it is ceasing all business operations effective October 23, 2000" (Press release). spaceprojects.com. 2000-03-23. http://www.spaceprojects.com/Beal/. Retrieved 2007-06-21.

- ^ "Roton". astronautix.com. http://www.astronautix.com/craft/roton.htm. Retrieved 2008-02-14.

- ^ "Falcon 9 booster rockets into orbit on dramatic first launch". SpaceflightNOW. June 4, 2010. http://spaceflightnow.com/falcon9/001/100604launch/index.html. Retrieved June 4, 2010.

- ^ Cowing, Keith (2006-03-06). "The SpaceX Dragon: America's First Privately Financed Manned Orbital Spacecraft?". SpaceRef.com. http://www.spaceref.com/news/viewnews.html?id=1095. Retrieved 2008-02-12.

- ^ [1]

- ^ Reaction Engines Limited FAQ

- ^ [2]

- ^ Reaction Engines Ltd 2006

- ^ "NASA and the Business of Space" (PDF). NASA. http://www.nasa.gov/pdf/138033main_griffin_aas1.pdf. Retrieved 2008-02-12.

- ^ "The Potential Impact of a LEO Propellant Depot on the NASA ESAS Architecture" (PDF). Boeing. http://www.boeing.com/defense-space/space/constellation/references/presentations/Potential_Impact_of_LEO_Propellant_on_NASA_ESAS_Architecture.pdf. Retrieved 2008-02-12.

- ^ "How Asteroid Mining Will Work". howstuffworks.com. http://science.howstuffworks.com/asteroid-mining1.htm. Retrieved 2008-02-12.

- ^ "The LiftPort Space Elevator". liftport.com. http://www.liftport.com/. Retrieved 2008-02-11.

- Belfiore, Michael. Rocketeers: How a Visionary Band of Business Leaders, Engineers, and Pilots is Boldly Privatizing Space. Harper Paperbacks, 2008.

- Bizony, Piers. How to Build Your Own Spaceship: The Science of Personal Space Travel. Plume, 2009.

External links

- Climbing a Commercial Stairway to Space: A Plausible Timeline RLV News, February 2, 2006

- An Introduction to Private Spaceflight Space Liberates Us!, March 20, 2007

- Study defining personal spaceflight industry Space Fellowship, May 29, 2008

Government

Corporate ventures

- C&SPACE

- Starchaser Industries

- Space Services, Inc.

- Commercial Space Companies at the Space Frontier Foundation

Media coverage

- A Word from the Know-Nothing Bureaucrats NASA union viewpoint on private spaceflight

- Private Industry Can Help NASA Open the Space Frontier Space Frontier Foundation, February 14, 2005

Space tourism Companies Armadillo Aerospace · Bigelow Aerospace · Blue Origin · EADS Astrium · Mojave Aerospace Ventures · Orbital Sciences Corporation · RocketShip Tours · Scaled Composites · Space Adventures · SpaceX · Virgin Galactic · XCOR Aerospace

Organizations Successful spacecraft Living in space Space competitions Spaceflight General

Applications Earth observation satellites (Spy satellites · Weather satellites) · Private spaceflight · Satellite navigation · Space archaeology · Space architecture · Space colonization · Space exploration · Space medicine · Space tourismHuman spaceflight GeneralHazardsMajor projectsApollo · Constellation · Gemini · International Space Station · Mercury · Mir · Shenzhou · Soyuz · Space Shuttle · Voskhod · VostokSpacecraft Destinations Space launch Space agencies Spaceflight lists and timelines General - All spaceflights

- Rocket and missile technology

- Space exploration

- milestones 1957–1969

Human spaceflight General- Manned spacecraft

- (timeline)

- Spaceflights

- 1961–1970

- 1971–1980

- 1981–1990

- 1991–2000

- 2001–2010

- 2011–present

- by program

- Soviet

- Russian

- Mercury

- Gemini

- Apollo

- Shenzhou

- Expeditions

- Spaceflights (manned

- unmanned)

- Spacewalks

- Visitors

- Expeditions

- Spaceflights (manned

- unmanned)

- Spacewalks

- Visitors

- Astronauts (Apollo

- by name

- by year of selection)

- Cosmonauts

- Married couples among space travelers

- Space travelers by name

- Space travelers by nationality

- (timeline)

- Spacewalks and moonwalks (1965–1999

- 2000–present)

- Cumulative spacewalk records

- Spacewalkers

Solar System exploration Earth-orbiting satellites - Climate research

- Communications satellite firsts

- CubeSats

- Earth observation satellites

- (timeline)

- Geosynchronous orbit

- GOES

- Kosmos

- Magnetospheric

- NRO

- TDRS

- USA

Vehicles - Orbital launch systems

- comparison of small lift launch systems

- comparison of medium lift launch systems

- comparison of orbital launch systems

- Sounding rockets

- Spacecraft (unmanned

- manned)

- Upper stages

Launches by rocket type - Ariane

- Atlas

- Black Brant

- Long March

- Proton

- R-7

- Thor and Delta

- Titan

- V-2 tests

Agencies, companies

and facilitiesOther mission lists

and timelinesCategories:- Private spaceflight

- Space applications

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.