- Parallel universe (fiction)

-

A parallel universe or alternative reality is a hypothetical self-contained separate reality coexisting with one's own. A specific group of parallel universes is called a "multiverse", although this term can also be used to describe the possible parallel universes that constitute reality. While the terms "parallel universe" and "alternative reality" are generally synonymous and can be used interchangeably in most cases, there is sometimes an additional connotation implied with the term "alternative reality" that implies that the reality is a variant of our own. The term "parallel universe" is more general, without any connotations implying a relationship, or lack of relationship, with our own universe. A universe where the very laws of nature are different – for example, one in which there are no relativistic limitations and the speed of light can be exceeded – would in general count as a parallel universe but not an alternative reality. The correct quantum mechanical definition of parallel universes is "universes that are separated from each other by a single quantum event."

Jorge Luis Borges' 1941 story "The Garden of Forking Paths" used the concept of parallel universes before the many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics had been developed.

Jorge Luis Borges' 1941 story "The Garden of Forking Paths" used the concept of parallel universes before the many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics had been developed.

Contents

Introduction

Fantasy has long borrowed the idea of "another world" from myth, legend and religion. Heaven, Hell, Olympus, Valhalla are all “alternative universes” different from the familiar material realm. Modern fantasy often presents the concept as a series of planes of existence where the laws of nature differ, allowing magical phenomena of some sort on some planes. This concept was also found in ancient Hindu mythology, in texts such as the Puranas, which expressed an infinite number of universes, each with its own gods.[1] Similarly in Persian literature, "The Adventures of Bulukiya", a tale in the One Thousand and One Nights, describes the protagonist Bulukiya learning of alternative worlds/universes that are similar to but still distinct from his own.[2] In other cases, in both fantasy and science fiction, a parallel universe is a single other material reality, and its co-existence with ours is a rationale to bring a protagonist from the author's reality into the fantasy's reality, such as in The Chronicles of Narnia by C. S. Lewis or even the beyond-the-reflection travel in the two main works of Lewis Carroll. Or this single other reality can invade our own, as when Margaret Cavendish's English heroine sends submarines and "birdmen" armed with "fire stones" back through the portal from The Blazing World to Earth and wreaks havoc on England's enemies. In dark fantasy or horror the parallel world is often a hiding place for unpleasant things, and often the protagonist is forced to confront effects of this other world leaking into his own, as in most of the work of H. P. Lovecraft and the Doom computer game series, or Warhammer/40K miniature and computer games. In such stories, the nature of this other reality is often left mysterious, known only by its effect on our own world.

The concept also arises outside the framework of quantum mechanics, as is found in Jorge Luis Borges short story El jardín de senderos que se bifurcan ("The Garden of Forking Paths"), published in 1941 before the many-worlds interpretation had been invented. In the story, a Sinologist discovers a manuscript by a Chinese writer where the same tale is recounted in several ways, often contradictory, and then explains to his visitor (the writer's grandson) that his relative conceived time as a "garden of forking paths", where things happen in parallel in infinitely branching ways. One of the first Sci-Fi examples is John Wyndham's Random Quest about a man who, on awaking after a laboratory accident, finds himself in a parallel universe where World War II never happened with consequences for his professional and personal life, giving him information he can use on return to his own universe.

While this is a common treatment in Sci-Fi, it is by no means the only presentation of the idea, even in hard science fiction. Sometimes the parallel universe bears no historical relationship to any other world; instead, the laws of nature are simply different than those in our own, as in the novel Raft by Stephen Baxter, which posits a reality where the gravitational constant is much larger than in our universe. (Note, however, that Baxter explains later in Vacuum Diagrams that the protagonists in Raft are descended from people who came from the Xeelee Sequence universe.)

One motif is that the way time flows in a parallel universe may be very different, so that a character returning to one might find the time passed very differently for those he left behind. This is found in folklore: King Herla visited Fairy and returned three centuries later; although only some of his men crumbled to dust on dismounting, Herla and his men who did not dismount were trapped on horseback, this being one folkloric account of the origin of the Wild Hunt.[3] C. S. Lewis made use of this in the Chronicles of Narnia; indeed, a character points out to two skeptics that there is no need for the time between the worlds to match up, but it would be very odd for the girl who claims to have visited a parallel universe to have dreamed up such a different time flow.[4]

The division between science fiction and fantasy becomes fuzzier than usual when dealing with stories that explicitly leave the universe we are familiar with, especially when our familiar universe is portrayed as a subset of a multiverse. Picking a genre becomes less a matter of setting, and more a matter of theme and emphasis; the parts of the story the author wishes to explain and how they are explained. Narnia is clearly a fantasy, and the TV series Sliders is clearly science fiction, but works like the World of Tiers series or Glory Road tend to occupy a much broader middle ground.

Parallel universes are considered parallel because there is no way of reaching them. All other dimensions are not parallel, but more than likely most of them are. An Einstein Rosen bridge, or Wormhole, can take you to a different dimension. Note that the journey through space-time continuum could backwards age you, or wipe you from existence. More than likely, if you managed to get to the alternate dimension, then you would have no memory of how you got there. The dangers of time-space travel are still being investigated, and possibilities are growing.

Typically, parallel universes fall into two classifications. The first may be more accurately called a "diverging universe" whereby two versions of Earth share a common history up to a point of divergence. At this point, the outcome of some even happens differently on the two Earths and the histories continue to become more different as time elapses since that point. (E.g. Parallels (Star Trek: The Next Generation). The second type is where despite certain, often large, difference between the two Earths history and/or culture, they maintain strong similarities. In such cases, it is common that every person in one universe will have a counterpart in the other universe with the same name, ancestry, appearance, and frequently occupation but often a very different personality. (e.g. Mirror, Mirror (Star Trek: The Original Series).

Science fiction

While technically incorrect, and looked down upon by hard science-fiction fans and authors, the idea of another “dimension” has become synonymous with the term “parallel universe”. The usage is particularly common in movies, television and comic books and much less so in modern prose science fiction. The idea of a parallel world was first introduced in comic books with the publication of Flash #123 - "Flash of Two Worlds".

In written science fiction, “new dimensions” more commonly — and more accurately — refer to additional coordinate axes, beyond the three spatial axes with which we are familiar. By proposing travel along these extra axes, which are not normally perceptible, the traveler can reach worlds that are otherwise unreachable and invisible.

Edwin A. Abbott's Flatland is set in a world of two dimensions.

Edwin A. Abbott's Flatland is set in a world of two dimensions.

In 1884, Edwin A. Abbott wrote the seminal novel exploring this concept called Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions. It describes a world of two dimensions inhabited by living squares, triangles, and circles, called Flatland, as well as Pointland (0 dimensions), Lineland (1 dimension), and Spaceland (three dimensions) and finally posits the possibilities of even greater dimensions. Isaac Asimov, in his foreword to the Signet Classics 1984 edition, described Flatland as "The best introduction one can find into the manner of perceiving dimensions."

In 1895, The Time Machine by H. G. Wells used time as an additional “dimension” in this sense, taking the four-dimensional model of classical physics and interpreting time as a space-like dimension in which humans could travel with the right equipment. Wells also used the concept of parallel universes as a consequence of time as the fourth dimension in stories like The Wonderful Visit and Men Like Gods, an idea proposed by the astronomer Simon Newcomb, who talked about both time and parallel universes; "Add a fourth dimension to space, and there is room for an indefinite number of universes, all alongside of each other, as there is for an indefinite number of sheets of paper when we pile them upon each other".[5]

There are many examples where authors have explicitly created additional spatial dimensions for their characters to travel in, to reach parallel universes. In Doctor Who, the Doctor accidentally enters a parallel universe while attempting to repair the TARDIS console in Inferno. The parallel universe was similar to the real universe but with some different aspects. Douglas Adams, in the last book of the Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy series, Mostly Harmless, uses the idea of probability as an extra axis in addition to the classical four dimensions of space and time similar to the many-worlds interpretation of quantum physics. Though, according to the novel, they're not really parallel universes at all but only a model to capture the continuity of space, time and probability. Robert A. Heinlein, in The Number of the Beast, postulated a six-dimensional universe. In addition to the three spatial dimensions, he invoked symmetry to add two new temporal dimensions, so there would be two sets of three. Like the fourth dimension of H. G. Wells’ "Time Traveller", these extra dimensions can be traveled by persons using the right equipment.

Hyperspace

Main article: Hyperspace (science fiction)Perhaps the most common use of the concept of a parallel universe in science fiction is the concept of hyperspace. Used in science fiction, the concept of “hyperspace” often refers to a parallel universe that can be used as a faster-than-light shortcut for interstellar travel. Rationales for this form of hyperspace vary from work to work, but the two common elements are:

- at least some (if not all) locations in the hyperspace universe map to locations in our universe, providing the "entry" and "exit" points for travellers.

- the travel time between two points in the hyperspace universe is much shorter than the time to travel to the analogous points in our universe. This can be because of a different speed of light, different speed at which time passes, or the analogous points in the hyperspace universe are just much closer to each other.

Sometimes "hyperspace" is used to refer to the concept of additional coordinate axes. In this model, the universe is thought to be "crumpled" in some higher spatial dimension and that traveling in this higher spatial dimension, a ship can move vast distances in the common spatial dimensions. An analogy is to crumple a newspaper into a ball and stick a needle straight through, the needle will make widely spaced holes in the two-dimensional surface of the paper. While this idea invokes a "new dimension", it is not an example of a parallel universe. It is a more scientifically plausible use of hyperspace. (See wormhole.)

Hyperspace may also refer to the entry and exit of subspace, an unproven area of the universe that lies below our own time-space and allows speeds exceeding light speed (not to be confused with faster-than-light travel).

While use of hyperspace is common, it is mostly used as a plot device and thus of secondary importance. While a parallel universe may be invoked by the concept, the nature of the universe is not often explored. So, while stories involving hyperspace might be the most common use of the parallel universe concept in fiction, it is not the most common source of fiction about parallel universes.

Time travel and alternate history

British author H. G. Wells' 1895 novel The Time Machine is an early example of time travel in modern fiction.

British author H. G. Wells' 1895 novel The Time Machine is an early example of time travel in modern fiction. Main articles: Time travel and Alternate history

Main articles: Time travel and Alternate historyThe most common use of parallel universes in science fiction, when the concept is central to the story, is as a backdrop and/or consequence of time travel. A seminal example of this idea is in Fritz Leiber’s novel, The Big Time where there’s a war across time between two alternate futures each side manipulating history to create a timeline that results into their own world.

Time-travelers in fiction often accidentally or deliberately create alternate histories, such as in The Guns of the South by Harry Turtledove where the Confederate Army is given the technology to produce AK-47 rifles and ends up winning the American Civil War. (However, Ward Moore reversed this staple of alternate history fiction in his Bring the Jubilee (1953), where an alternative world where the Confederate States of America won the Battle of Gettysburg and the American Civil War is destroyed after a historian and time traveller from the defeated United States of that world travels back to the scene of the battle and inadvertently changes the result so that the North wins that battle.) The alternate history novel 1632 by Eric Flint explicitly states, albeit briefly in a prologue, that the time travelers in the novel (an entire town from West Virginia) have created a new and separate universe when they're transported into the midst of the Thirty Years War in 17th century Germany. (This sort of thing is known as an ISOT among alternate history fans, after S.M. Stirling's Island in the Sea of Time: an ISOT is when territory or a large group of people is transported back in time to another historical period or place.[citation needed]

Typically, alternate histories are not technically parallel universes. Though the concepts are similar, there are significant differences. In cases where characters travel to the past, they may cause changes in the timeline (creating a point of divergence) that result in changes to the present. The alternate present will be similar in different degrees to the original present as would be the case with a parallel universe. The main difference is that parallel universes co-exist whereas only one history or alternate history can exist at any one moment. Another difference is that travelling to a parallel universe involves some type of inter-dimensional travel whereas alternative histories involve some type of time travel. (However, since the future is only potential and not actual, it is often conceived that more than one future may exist simultaneously.)

The concept of "sidewise" time travel, a term taken from Murray Leinster's "Sidewise in Time", is often used to allow characters to pass through many different alternate histories, all descendant from some common branch point. Often worlds that are similar to each other are considered closer to each other in terms of this sidewise travel. For example, a universe where World War II ended differently would be “closer” to us than one where Imperial China colonized the New World in the 15th century. H. Beam Piper used this concept, naming it "paratime" and writing a series of stories involving the Paratime Police who regulated travel between these alternative realities as well as the technology to do so. Keith Laumer used the same concept of "sideways" time travel in his 1962 novel Worlds of the Imperium. More recently, novels such as Frederik Pohl's The Coming of the Quantum Cats and Neal Stephenson's Anathem explore human-scale readings of the "many worlds" interpretation of quantum mechanics, postulating that historical events or human consciousness spawns or allows "travel" among alternate universes.

Frequent 'types' of universe explored in sidewise and alternative history works include worlds in which the Nazis won the Second World War, such as in The Man in the High Castle by Philip K. Dick, SS-GB by Len Deighton and Fatherland by Robert Harris, and worlds in which the Roman Empire never fell, such as in Roma Eterna by Robert Silverberg and Romanitas by Sophia McDougall. In his novel Warlords of Utopia, part of the loosely linked Faction Paradox series, Lance Parkin explored a multiverse in which every universe in which Rome never fell goes to war with every universe in which the Nazis won WWII. The series was created by Lawrence Miles, whose earlier work Dead Romance featured the concept of an artificially created universe existing within another -specifically, within a bottle - and explored the consequences of inhabitants of the 'real' universe entering the Universe-in-a-Bottle.

In the His Dark Materials trilogy, the universe the protagonist starts in is a Victorian counterpart to ours, although it takes place at the same time. It also appears that the Protestant Reformation never happened.

In his short story, Rumfuddle, Jack Vance invents a doorway to an infinite number of universes at any given time, so that everyone on the planet can have their own private world. Some are inhabited by humans. On some, man doesn't exist. The trouble comes when some of the Rumfuddlers (a term given to an annual gathering to see who can best mess around with what should be) play pranks on parallel world, such as switching the infant Adolf Hitler with a baby from a Jewish couple, or putting together a football team made up of all of the great men in history.

Counter-Earth

The concept of Counter-Earth is typically similar to that of parallel universes but is actually a distinct idea. A counter-earth is a planet that shares Earth's orbit but is on the opposite side of the Sun and therefore cannot be seen from Earth. There would be no necessity that such a planet would be like Earth in any way though typically in fiction, it is usually nearly identical to Earth. Since counter-earth is always within our own universe (and our own solar system), travel to it can be accomplished with ordinary space travel.

See Counter-Earth for literary and film examples.

Convergent evolution

Convergent evolution is a biological concept whereby unrelated species acquire similar traits because they adapted to a similar environment and/or played similar roles in their ecosystems. In fiction, the concept is extended whereby similar planets will result in races with similar cultures and/or histories.

Technically this is not a type of parallel universe since such planets can be reached via ordinary space travel, but the stories are similar in some respects.

In "Bread and Circuses (Star Trek: The Original Series)", the enterprise encounters a planet called Magna Roma which has many physical resemblances to Earth such as its atmosphere, land to ocean ratio, and size. The landing party discovers that the planet is at roughly a late 20th-century level of technology but its society is similar to the Roman Empire. It was as if the Roman Empire had not fallen but had continued to that time. There is also a reference to the Roman god Jupiter. At the end of the episode, it is discovered that their own version Jesus, referred simply as "the son".

In The Omega Glory (Star Trek), the crew visit a planet on which there is a conflict between two peoples called the Yangs and the Kohms. They discover that the Yangs are like Earth's Yankees (i.e. Americans) and the Kohms are like Earth's communists. The Yangs had a constitution that was word for word identical to the American constitution but at some point in the past the Kohms had taken over.

In Miri (Star Trek: The Original Series), the Enterprise crew encounter a planet (later called Onlies) that is physically identical to Earth. History on the two planets were apparently identical until the 20th centuries when scientists on Onlies had accidentally created a deadly virus that killed all the adults but extended the lives of the children.

Convergent Evolution due to contamination

As similar concept in biology is gene flow. In this case, a planet may start as different from Earth, but due to the influence of Earth culture, the planet come to resemble Earth in some way.

Technically this is not a type of parallel universe since such planets can be reached via ordinary space travel, but the stories are similar in some respects.

In Patterns of Force (Star Trek: The Original Series), a planet is discovered that has become very similar to Nazi Germany due to the influence of a professor that came to reside there. In A Piece of the Action (Star Trek: The Original Series), the Enterprise crew visits a planet that resembles mob ruled cities of Earth in the 1920's due to a book titled "Chicago Mobs of the Twenties" that had been left behind by previous Earth craft.

Fantasy

Stranger in a strange land

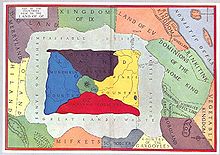

Oz and its surroundings.

Oz and its surroundings.

Fantasy authors often want to bring characters from the author's (and the reader's) reality into their created world. Before the mid-20th century, this was most often done by hiding fantastic worlds within hidden parts of the author's own universe. Peasants who seldom if ever traveled far from their villages could not conclusively say that it was impossible that an ogre or other fantastical beings could live an hour away, but increasing geographical knowledge meant that such locations had to be farther and farther off.[6] Characters in the author's world could board a ship and find themselves on a fantastic island, as Jonathan Swift does in Gulliver's Travels or in the 1949 novel Silverlock by John Myers Myers, or be sucked up into a tornado and land in Oz. These "lost world" stories can be seen as geographic equivalents of a "parallel universe", as the worlds portrayed are separate from our own, and hidden to everyone except those who take the difficult journey there. The geographic "lost world" can blur into a more explicit "parallel universe" when the fantasy realm overlaps a section of the "real" world, but is much larger inside than out, as in Robert Holdstock's novel Mythago Wood.

After the mid-20th century, perhaps influenced by ideas from science fiction, perhaps because exploration had made many places on the map too clear to write "Here there be dragons", many fantasy worlds became completely separate from the author's world.[6] A common trope is a portal or artifact that connects worlds together, prototypical examples being the wardrobe in C. S. Lewis' The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, or the sigil in James Branch Cabell's The Cream of the Jest. In Hayao Miyazaki's Spirited Away, Chihiro Ogino and her parents climb over a small stream into the spirit world. The main difference between this type of story and the "lost world" above, is that the fantasy realm can only be reached by certain people, or at certain times, or after following certain rituals, or with the proper artifact.

In some cases, physical travel is not even possible, and the character in our reality travels in a dream or some other altered state of consciousness. Examples include the Dream Cycle stories by H. P. Lovecraft or the Thomas Covenant stories of Stephen R. Donaldson. Often, stories of this type have as a major theme the nature of reality itself, questioning if the dream-world can have the same "reality" as the waking world. Science fiction often employs this theme (usually without the dream-world being "another" universe) in the ideas of cyberspace and virtual reality.

Between the worlds

Most stories in this mold simply transport a character from the real world into the fantasy world where the bulk of the action takes place. Whatever gate is used – such as the tollbooth in The Phantom Tollbooth by Norton Juster, or the mirror in Lewis Carroll's Through the Looking-Glass – is left behind for the duration of the story, until the end, and then only if the protagonists will return.

However, in a few cases the interaction between the worlds is an important element, so that the focus is not on one world or the other, but on both, and their interaction. After Rick Cook introduced a computer programmer into a high fantasy world, his wizardry series steadily acquired more interactions between this world and ours. In Aaron Allston's Doc Sidhe our "grim world" is paralleled by a "fair world" where the elves live and history echoes ours. A major portion of the plot deals with preventing a change in interactions between the worlds. Margaret Ball, in No Earthly Sunne, depicts the interaction of our world with Faerie, and the efforts of the Queen of Faerie to deal with the slow drifting apart of Earth and Faerie. Poul Anderson depicts Hell as a parallel universe in Operation Chaos, and the need to transfer equivalent amounts of mass between the worlds explains why a changeling is left for a kidnapped child. Interactions between magical and scientific universes, and the protagonists' attempts to restore and maintain the balance between them, are major plot points in Piers Anthony's Apprentice Adept series; he depicts two worlds, the "SF" planet Proton and the fantasy-based Phaze, such that every person born in either world has a physical duplicate on the other world. Only when one duplicate has died can the other cross between the worlds. Several of his Xanth novels also revolve around interactions between the magical realm of Xanth and "Mundania".

Multiple worlds, rather than a pair, increase the importance of the relationships. In The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, there are only our world and Narnia, but in other of C. S. Lewis's works, there are hints of other worlds, and in The Magician's Nephew, the Wood between the Worlds shows many possibilities, and the plot is governed by transportation between worlds, and the effort to right problems stemming from them. In His Dark Materials, the two protagonist Lyra and Will find themselves lost amongst many worlds, and travel them looking for the other. In Andre Norton's Witch World, begun with a man from Earth being transported to this world, gates frequently lead to other worlds — or come from them. While an abundance of illusions, disguises, and magic that repels attention make certain parts of Witch World look like parallel worlds, some are clearly parallel in that time runs differently in them, and such gates pose a repeated problem in Witch World. In the radio sitcom Undone, the main character, Edna Turner, prevents people from a parallel version of London called "Undone" from moving to London and making the city too weird. There are other parallel versions of London, and one of the main plots in the series is the attempt by The Prince to unite all versions of London together.

Linking rooms of various types (not all actual rooms) can hook together any number of worlds. The characters may chose only one, but the choice is all important in determining the worlds.

Fantasy multiverses

The idea of a multiverse is as fertile a subject for fantasy as it is for science fiction, allowing for epic settings and godlike protagonists. Among the most epic and far-ranging fantasy "multiverses" is that of Michael Moorcock. Like many authors after him, Moorcock was inspired by the many worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics, saying:

It was an idea in the air, as most of these are, and I would have come across a reference to it in New Scientist (one of my best friends was then editor) ... [or] physicist friends would have been talking about it. ... Sometimes what happens is that you are imagining these things in the context of fiction while the physicists and mathematicians are imagining them in terms of science. I suspect it is the romantic imagination working, as it often does, perfectly efficiently in both the arts and the sciences.[citation needed]

Unlike many science-fiction interpretations, Moorcock's Eternal Champion stories go far beyond alternate history to include mythic and sword and sorcery settings as well as some worlds more similar to our own. However, the Eternal Champion himself is incarnate in all of them.

Roger Zelazny used a mythic cosmology in his Chronicles of Amber series. His protagonist is a member of the royal family of Amber, whose members represent a godlike pantheon ruling over a prototypical universe that represents Order. All other universes are increasingly distorted "shadows" of it, ending finally at the other extreme, Chaos, which is the complete negation of the prototype. Travel between these "shadow" universes is only possible by beings descended from the blood of this pantheon. Those "of the blood" can walk through Shadow, imagining any possible reality and then walk to it, making their environment more similar to their desire as they go. It is argued between the characters whether these "shadows" even exist before they're imagined by a member of the royal family of Amber, or if the "shadows'" existence can be seen as an act of godlike creation.

In the World of Tiers novels by Philip José Farmer, the idea of godlike protagonists is even more explicit. The background of the stories is a multiverse where godlike beings have created a number of pocket universes that represent their own desires. Our own world is part of this series, but interestingly our own universe is revealed to be much smaller than it appears, ending at the edge of the solar system.

The term 'polycosmos' was coined as an alternative to 'multiverse' by the author and editor Paul le Page Barnett, best known by the pseudonym John Grant, and is built from Greek rather than Latin morphemes. It is used by Barnett to describe a concept binding together a number of his works, its nature meaning that "all characters, real or fictional [...] have to co-exist in all possible real, created or dreamt worlds; [...] they're playing hugely different roles in their various manifestations, and the relationships between them can vary quite dramatically, but the essence of them remains the same."[7]

There are multiverses also in the Warcraft universe, The Chronicles of Narnia, Terry Pratchett's Discworld series, and Diana Wynne Jones's Chrestomanci, Howl's Moving Castle and Deep Secret books and standalone book A Sudden Wild Magic.

Fictional universe as alternative universe

Main article: Fictional universeThere are many examples of the meta-fictional idea of having the author's created universe (or any author's universe) rise to the same level of "reality" as the universe we're familiar with. The theme is present in works as diverse as Myers' Silverlock and Heinlein’s Number of the Beast. Fletcher Pratt and L. Sprague de Camp took the protagonist of the Harold Shea series through the worlds of Norse myth, Edmund Spenser's Faerie Queene, Ludovico Ariosto's Orlando Furioso, and the Kalevala[8]— without ever quite settling whether writers created these parallel worlds by writing these works, or received impressions from the worlds and wrote them down. In an interlude set in "Xanadu", a character claims that the universe is dangerous because the poem went unfinished, but whether this was his misapprehension or not is not established.

Some fictional approaches definitively establish the independence of the parallel world, sometimes by having the world differ from the book's account; other approaches have works of fiction create and affect the parallel world: L. Sprague de Camp's Solomon's Stone, taking place on an astral plane, is populated by the daydreams of mundane people, and in Rebecca Lickiss's Eccentric Circles, an elf is grateful to Tolkien for transforming elves from dainty little creatures. These stories often place the author, or authors in general, in the same position as Zelazny's characters in Amber. Questioning, in a literal fashion, if writing is an act of creating a new world, or an act of discovery of a pre-existing world.

Occasionally, this approach becomes self-referential, treating the literary universe of the work itself as explicitly parallel to the universe where the work was created. Stephen King's seven-volume Dark Tower series hinges upon the existence of multiple parallel worlds, many of which are King's own literary creations. Ultimately the characters become aware that they are only "real" in King's literary universe (this can be debated as an example of breaking the fourth wall), and even travel to a world — twice — in which (again, within the novel) they meet Stephen King and alter events in the real Stephen King's world outside of the books. An early instance of this was in works by Gardner Fox for DC Comics in the 1960s, in which characters from the Golden Age (which was supposed to be a series of comic books within the DC Comics universe) would cross over into the main DC Comics universe. One comic book did provide an explanation for a fictional universe existing as a parallel universe. The parallel world does "exist" and it resonates into the "real world." Some people in the "real world" pick up on this resonance, gaining information about the parallel world which they then use to write stories.

Elfland

Main article: ÁlfheimElfland, or Faerie, the otherworldly home not only of elves and fairies but goblins, trolls, and other folkloric creatures, has an ambiguous appearance in folklore.

On one hand, the land often appears to be contiguous with 'ordinary' land. Thomas the Rhymer might, on being taken by the Queen of Faerie, be taken on a road like one leading to Heaven or Hell.

This is not exclusive to English or French folklore. In Norse mythology, Elfland (Alfheim) was also the name of what today is the Swedish province of Bohuslän. In the sagas, it said that the people of this petty kingdom were more beautiful than other people, as they were related to the elves, showing that not only the territory was associated with elves, but also the race of its people.

While sometimes folklore seems to show fairy intrusion into human lands — "Tam Lin" does not show any otherworldly aspects about the land in which the confrontation takes place — at other times the otherworldly aspects are clear. Most frequently, time can flow differently for those trapped by the fairy dance than in the lands they come from; although, in an additional complication, it may only be an appearance, as many returning from Faerie, such as Oisín, have found that time "catches up" with them as soon as they have contact with ordinary lands.

Fantasy writers have taken up the ambiguity. Some writers depict the land of the elves as a full-blown parallel universe, with portals the only entry — as in Josepha Sherman's Prince of the Sidhe series or Esther Friesner's Elf Defense — and others have depicted it as the next land over, possibly difficult to reach for magical reasons — Hope Mirrlees's Lud-in-the-Mist, or Lord Dunsany's The King of Elfland's Daughter. In some cases, the boundary between Elfland and more ordinary lands is not fixed. Not only the inhabitants but Faerie itself can pour into more mundane regions. Terry Pratchett's Discworld series proposes that the world of the Elves is a "parasite" universe, that drifts between and latches onto others such as Discworld and our own world (referred to as "Roundworld" in the novels).

Films

In Frank Capra's It's A Wonderful Life (1946), George Bailey (center, played by James Stewart) is shown by his guardian angel how the world would have been radically different for the worse if Bailey had never existed.

In Frank Capra's It's A Wonderful Life (1946), George Bailey (center, played by James Stewart) is shown by his guardian angel how the world would have been radically different for the worse if Bailey had never existed.

The most famous treatment of the alternative universe concept in film could be considered The Wizard of Oz, which portrays a parallel world, famously separating the magical realm of the Land of Oz from the mundane world by filming it in Technicolor while filming the scenes set in Kansas in sepia.

A later example is the Frank Capra movie, It's a Wonderful Life where the main character George Bailey is shown by a guardian angel the city of Pottersville, which was George Bailey's hometown of Bedford Falls as it would have been if he had never existed. Another notable depiction of a parallel universe in movies is in Back to the Future Part II by Robert Zemeckis, starring Michael J. Fox and Christopher Lloyd, showing an accidentally created alternative present and future. Like It's a Wonderful Life, The Big Time, and many other time travel stories using this concept, it is clear that these alternative presents/futures are mutually exclusive with the protagonists' own — so, strictly speaking, the universes are not parallel in that they cannot co-exist, rather they oscillate between one or the other.

Another common use of the theme is as a prison for villains or demons. The idea is used in the first two Superman movies starring Christopher Reeve where Kryptonian villains were sentenced to the Phantom Zone from where they eventually escaped. An almost exactly parallel use of the idea is presented in the campy cult film The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai Across the 8th Dimension, where the "8th dimension" is essentially a "phantom zone" used to imprison the villainous Red Lectroids. Uses in horror films include the 1986 film From Beyond (based on the H. P. Lovecraft story of the same name) where a scientific experiment induces the experimenters to perceive aliens from a parallel universe, with bad results. The 1987 John Carpenter film Prince of Darkness is based on the premise that the essence of a being described as Satan, trapped in a glass canister and found in an abandoned church in Los Angeles, is actually an alien being that is the 'son' of something even more evil and powerful, trapped in another universe. The protagonists accidentally free the creature, who then attempts to release his "father" by reaching in through a reflective glass, or mirror.

Some films present parallel realities that are actually different contrasting versions of the narrative itself. Commonly this motif is presented as different points of view revolving around a central (but sometimes unknowable) "truth", the seminal example being Akira Kurosawa's Rashomon. Conversely, often in film noir and crime dramas, the alternative narrative is a fiction created by a central character, intentionally — as in The Usual Suspects — or unintentionally — as in Angel Heart. Less often, the alternative narratives are given equal weight in the story, making them truly alternative universes, such as in the German film Run Lola Run, the short-lived British West End musical Our House and the British film Sliding Doors.

More recent films that have explicitly explored parallel universes are: the 2000 film The Family Man, the 2001 cult movie Donnie Darko, which deals with what it terms a "tangent universe" that erupts from our own universe; Super Mario Bros. (1993) has the eponymous heroes cross over into a parallel universe ruled by humanoids who evolved from dinosaurs; The One (2001) starring Jet Li, in which there is a complex system of realities in which Jet Li's character is a police officer in one universe and a serial killer in another, who travels to other universes to destroy versions of himself, so that he can take their energy; and FAQ: Frequently Asked Questions (2004), the main character runs away from a totalitarian nightmare, and he enters into a cyber-afterlife alternative reality. The most recent Star Trek film (2009) had a character create an alternate reality by traveling back in time, thereby rebooting the series' complicated continuity.

The film director and screenwriter Quentin Tarentino has been known to create his own brand of reality for each of his movies and for his subjects. In his 2009 film Inglorious Basterds, he created his most effective story in showcasing this kind of creation. At the climax of this film his soldiers trap, surround, and then assassinate both Nazi leader Adolf Hitler and all of his entire High Command (the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht) in a burning Paris, France movie theater in an alternate 1944, theoretically ending the war.

Television

The idea of parallel universes have received treatment in a number of television series, usually as a single story or episode in a more general science fiction or fantasy storyline.

One of the earliest television plots to feature parallel time was a 1970 storyline on soap opera Dark Shadows. Vampire Barnabas Collins found a room in Collinwood which served as a portal to parallel time, and he entered the room in order to escape from his current problems. A year later, the show again traveled to parallel time, the setting this time being 1841.

A well known and often imitated example is the original Star Trek episode entitled "Mirror, Mirror". The episode introduced an alternative version of the Star Trek universe where the main characters were barbaric and cruel to the point of being evil. When the parallel universe concept is parodied, the allusion is often to this Star Trek episode. A previous episode for the Trek series first hinted at the potential of differing reality planes (and their occupants) -titled "The Alternative Factor". A mad scientist from "our" universe, named Lazarus B., hunts down the sane Lazarus A.; resident of an antimatter-comprised continuum. His counterpart, in a state of paranoia, claims the double threatens his and the very cosmos' existence. With help from Captain Kirk, A traps B along with him in a "anti"-universe, for eternity, thus bringing balance to both matter oriented realms. A similar plot was used in the Codename: Kids Next Door episode Operation: P.O.O.L..

Multiple episodes of Red Dwarf use the concept. In "Parallel Universe" the crew meet alternative versions of themselves: the analogues of Lister, Rimmer and Holly are female, while the Cat's alternate is a dog. "Dimension Jump" introduces a heroic alternate Rimmer, a version of whom reappears in "Stoke Me a Clipper". The next episode, "Ouroboros", makes contact with a timeline in which Kochanski, rather than Lister, was the sole survivor of the original disaster; this alternate Kochanski then joins the crew for the remaining episodes.

Another example is "Spookyfish", an episode of South Park, in which the "evil" universe double of Cartman (who is pleasant and agreeable, unlike the home universe's obnoxious Cartman) sports a goatee, like the "mirror" version of Mr. Spock.

Buffy the Vampire Slayer experienced a Parallel universe where she was a mental patient in Normal Again and not really "The Slayer" at all. In the end, she has to choose between a universe where her mother and father are together and alive (mother) or one with her friends and sister in it where she has to fight for her life daily.

The animated series, Futurama, had an episode where the characters travel between "Universe A" and "Universe 1" via boxes containing each universe; and one of the major jokes is an extended argument between the two sets of characters over which set were the "evil" ones.

Doctor Who often features parallel universes as the basis of a plotline. In the episode "Inferno", from Doctor Who the Doctor accidentally travels to a parallel universe where Great Britain is a republic under a fascist leader. In "Rise of the Cybermen", the TARDIS falls out of the Time-Space Continuum, and dies, with the Doctor and his companions inside it. The Doctor believes them to be in the Void, the infinite empty-space between the universes, where no time, space or energy exists. It turns out, however, they fell into another universe; a much more desirable option. In this universe, Britain is a lot more technically advanced, with blimps almost replacing cars. They find a way to revive the TARDIS and travel back to their own universe. According to the Doctor in "Doomsday", a new parallel universe is created by every decision made.

The OC had an episode where two main characters fell into a coma, and into an alternate/parallel universe.

Friends had an episode in which the characters wonder how different their lives would be with different choices.

Parallel universes/alternate futures are also featured in Heroes.

The idea of a parallel universe and the concept of deja vu was a major plot line of the first season finale of Fringe, guest-starring Leonard Nimoy of Star Trek. The show has gone on to feature the parallel universe prominently.

In the 2010 season of Lost, the result of characters traveling back in time to prevent the crash of Oceanic Flight 815 apparently creates a parallel reality in which the Flight never crashed, rather than resetting time itself in the characters' original timeline. The show continued to show two "sets" of the characters following different destinies, until it was revealed in the series finale that there was really only one reality created by the characters themselves to assist themselves in leaving behind the physical world and passing on to an afterlife after their respective deaths.

The anime Turn A Gundam attempted to combine all the parallel Gundam universes (other incarnations of the series, with similar themes but differing stories and characters, that had played out at different times since the debut of the concept in the 1970s) of the metaseries in to one single reality.

The anime Neon Genesis Evangelion features a parallel world in one of the final episodes. This parallel world is a sharp contrast to the harsh, dark "reality" of the show and presents a world where all the characters enjoy a much happier life. This parallel world would become the basis for the new Evangelion manga series Angelic Days.

The anime Bakugan series in season 2 & 3 features another unverses where Dan and his team saves the day.They goes to another dimension or universe through a path way . Another universe has also other life forms and other types of technology.

In another anime Digimon series there is parallel universe called "digital world". The show's child protagonists meet digital monsters, or digimon, from this world and becomes partners and friends.

In the animated Disney series Darkwing Duck, the title character's archenemy, Negaduck, comes from a parallel dimension called the Negaverse (not to be confused with the similarly named dimension in the Sailor Moon series).

In the Family Guy episode, "Road to the Multiverse", Brian and Stewie get a look at life in other universes that are at the same time and place as Quahog, but under different conditions.

In the Star Trek: The Next Generation episode "Parallels", Lt. Worf traveled to several parallel universes when his shuttlecraft went through a time space fissure.

The movie for Phineas and Ferb involves Phineas, Ferb, and Perry going to an alternate dimension of the Tri-state area.

As an ongoing subplot

Sometimes a television series will use parallel universes as an ongoing subplot. Star Trek: Deep Space Nine and Star Trek: Enterprise elaborated on the premise of the original series' "Mirror" universe and developed multi-episode story arcs based on the premise. Other examples are the science fiction series Stargate SG-1, the fantasy/horror series Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Supernatural and the romance/fantasy Lois & Clark: The New Adventures of Superman.

Following the precedent set by Star Trek, these story arcs show alternative universes that have turned out "worse" than the "original" universe: in Stargate SG-1 the first two encountered parallel realities featured Earth being overwhelmed by an unstoppable Goa'uld onslaught; in Buffy, two episodes concern a timeline in which Buffy came to Sunnydale too late to stop the vampires from taking control; Lois & Clark repeatedly visits an alternative universe where Clark Kent's adoptive parents, Jonathan and Martha Kent, died when he was ten years of age, and Lois Lane is also apparently dead. Clark eventually becomes Superman, with help from the "original" Lois Lane, but he is immediately revealed as Clark Kent and so has no life of his own.

In addition to following Star Trek's lead, showing the "evil" variants of the main storyline gives the writers an opportunity to show what is at stake by portraying the worst that could happen and the consequences if the protagonists fail or the importance of a character's presence. The latter could also be seen as the point of the alternative reality portrayed in the movie It's a Wonderful Life.

Parallel universe-based series

There have been a few series where parallel universes were central to the series itself. Two examples are:

- Sliders, where a young man invents a worm-hole generator that allows travel to "alternative" Earths. Several characters travel across a series of "alternative" Earths, trying to get back to their home universe;

- Charlie Jade, in which the titular character is accidentally thrown into our universe and is looking for a way back to his own. The series features three universes - alpha, beta and gamma.

In 1986, Disney produced a pilot episode for an animated children's show about interdimensional travel called Fluppy Dogs.

In the TV series Fringe, an ongoing subplot of the series is the loss of balance and the eventual collision of two universes and the moral ramifications of it.

Comic books

Parallel universes in modern comics have become particularly rich and complex, in large part due to the continual problem of continuity faced by the major two publishers, Marvel Comics and DC Comics. The two publishers have used the multiverse concept to fix problems arising from integrating characters from other publishers into their own canon, and from having major serial protagonists having continuous histories lasting, as in the case of Superman, over 70 years. Additionally, both publishers have used new alternative universes to re-imagine their own characters. (See Multiverse (DC Comics) and Multiverse (Marvel Comics))

Because of this, comic books in general are one of the few entertainment mediums where the concept of parallel universes are a major and ongoing theme. DC in particular periodically revisits the idea in major crossover storylines, such as Crisis on Infinite Earths and Infinite Crisis, where Marvel has a series called What If... that's devoted to exploring alternative realities, which sometimes impact the "main" universe's continuity. DC's version of "What If..." is the Elseworlds imprint.

Recently DC Comics series 52 heralded the return of the Multiverse. 52 was a mega-crossover event tied to Infinite Crisis which was the sequel to the 1980s Crisis on Infinite Earths. The aim was to yet again address many of the problems and confusions brought on by the Multiverse in the DCU. Now 52 Earths exist and including some Elseworld tales such as Kingdom Come, DC's imprint Wildstorm Comics and an Earth devoted to the Charlton Comics heroes of DC. Countdown and Countdown Presents: The Search for Ray Palmer and the upcoming Tales of the Multiverse stories expand upon this new Multiverse.

Marvel has also had many large crossover events which depicted an alternative universe, many springing from events in the X-Men books, such as Days of Future Past, the seminal Age Of Apocalypse, and 2006's House Of M. In addition the Squadron Supreme is a DC inspired Marvel Universe that has been used several times, often crossing over into the mainstream Universe in the Avengers comic. Exiles is an offshoot of the X-Men franchsie that allows characters to hop from one alternative reality to another, leaving the original, main Marvel Universe intact. The Marvel UK line has long had multiverse stories including the Jaspers' Warp storyline of Captain Britain's first series (it was here that the designation Earth-616 was first applied to the mainstream Marvel Universe).

Marvel Comics, as of 2000, launched their most popular parallel universe, the Ultimate Universe. It is a smaller subline to the mainstream titles and features Ultimate Spider-Man, Ultimate X-Men, Ultimate Fantastic Four and the Ultimates (their "Avengers"). The line in many ways both inspired and was inspired by aspects of the new movie franchises in addition to creating younger versions of the modern heroes.

The graphic novel Watchmen is set in an alternate history in 1985 where superheroes exist, the Vietnam War was won by the United States, and Richard Nixon is in his fifth term as President of the United States. The Soviet Union and the United States are still in a "Cold War" with a threat of a Nuclear War impending.

In 1973 Tammy published The Clock and Cluny Jones, where a mysterious grandfather clock hurls bully Cluny Jones into a harsh alternate reality where she becomes the bullied. This story was reprinted in Misty annual 1985 as Grandfather's Clock.

In 1978 Misty published The Sentinels. The Sentinels were two crumbling apartment blocks that connected the mainstream world with an alternate reality where Hitler conquered Britain in 1940.

In 1981 Jinty published Worlds Apart. Six girls experience alternate worlds ruled by greed, sports-mania, vanity, crime, intellectualism, and fear. These are in fact their dream worlds becoming real after they are knocked out by a mysterious gas from a chemical tanker that crashed into their school. In 1977 Jinty also published Land of No Tears where a lame girl travels to a future world where people with things wrong with them are cruelly treated, and emotions are banned.

Video games

In the 1999 role-playing game Outcast where a probe is sent to a parallel universe and is attacked by an "entity". Cutter Slade must escort a team of scientists across to the other world to retrieve and repair the damaged probe before the earth is consumed by a black hole.

In the survival horror video game series Silent Hill, the town of Silent Hill fluctuates between the normal world, a foggy version of the town and a dark and dilapidated version of the town called the "Other World".

In the 1993 adventure PC game Myst, the unnamed protagonist travels to multiple alternate worlds through the use of special books, which describe a world within and transport the user to that world when a window on the front page is touched.

In the 1996 adventure PC game 9: The Last Resort, after resolving several mind-blowing and unique puzzles, the player gets past "The Tiki Guards" and a door to "The Void" opens up - actually a room to another universe which houses the entirety of space.

Both titles of the When They Cry Visual Novel series (Higurashi and Umineko for short) contain the concept of parallel worlds. These series both involve some kind of murder mystery occurring. As soon as the main character has 'lost', another parallel world, called a Fragment, is chosen to be observed. This continues until the entire mystery is solved.

The video game The Legend of Cheese: A Link to the Past features a dark and twisted parallel version of Hyrule called the "Dark World".

The story of Chrono Cross centers around travel between two alternate timelines, the original or "Home" universe and "Another World" which is a branch created by the actions of the heroes of the game's predecessor, Chrono Trigger.

The video game series Legacy of Kain is played through several realms and timelines.

The video game Sudeki is set in a realm of light and a parallel realm of darkness.

The video game The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion features an alternative hellish world called "Oblivion", as well as a painting you can climb into and a quest where you enter a dream world.

The video game The Legend of Zelda: Majora's Mask takes place in Termina, a parallel world to Hyrule.

The video game The Darkness pivots around a world of darkness you travel to when you die, which is occupied by World War 1 soldiers.

The video game Metroid Prime 2: Echoes involves a world, "Aether", having an alternate self in the, "Dark" realm, universe, or dimension. The protagonist, Samus, finds out that she just dropped in to a hopeless war for the Luminoth, the dominant species of Light Aether against the Ing, the dominant species of Dark Aether. She also finds her counterpart, Dark Samus or Metroid Prime's essence inside Samus's Phazon Suit.

The video game Crash Twinsanity features Crash,Cortex,and Nina traveling to the "10th dimension" which could also be a parelell universe (suggesting by the theme and how everything seems to be opposite)

The video game Minecraft features an alternate dimension called "The Nether", that includes a 'hell' like theme.

The video game Persona 2: Eternal Punishment (The second part of the Persona 2) takes place in an alternate universe called "This Side" where in the events of Innocent Sin did not take place and the characters have never met in the past.

In the video game Epic Mickey you travel through old Mickey Mouse movie reels.

See also

- Alternative universe (fan fiction)

- Imaginary world

- List of fiction employing parallel universes

- World as Myth

- Multiverse

References

Notes

- ^ Carl Sagan, Placido P D'Souza (1980s). Hindu cosmology's time-scale for the universe is in consonance with modern science.; Dick Teresi (2002). Lost Discoveries : The Ancient Roots of Modern Science - from the Babylonians to the Maya.

- ^ Irwin, Robert (2003). The Arabian Nights: A Companion. Tauris Parke Paperbacks. p. 209. ISBN 1860649831.

- ^ Briggs (1967) p.50-1

- ^ Gareth Matthews, "Plato in Narnia" p 171 Gregory Bassham ed. and Jerry L. Walls, ed. The Chronicles of Narnia and Philosophy ISBN 0-8126-9588-7

- ^ Stephen Baxter Speech

- ^ a b C. S. Lewis, "On Science Fiction", Of Other Worlds, p68 ISBN 0-15-667897-7

- ^ "John Grant" interviewed by Lou Anders, accessed 24 October 2009

- ^ Michael Moorcock, Wizardry & Wild Romance: A Study of Epic Fantasy p 88 ISBN 1-932265-07-4

Further reading

- Clifford A. Pickover (August 2005). Sex, Drugs, Einstein, and Elves: Sushi, Psychedelics, Parallel Universes, and the Quest for Transcendence (Discusses parallel universes in a variety of settings, from physics to psychedelic visions to Proust parallel worlds to Bonnet syndrome). Smart Publications. ISBN 1-890572-17-9.

- Michio Kaku (2004). Parallel Worlds: A Journey Through Creation, Higher Dimensions, and the Future of the Cosmos. Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-50986-3.

External links

- Max Tegmark's Parallel Universes paper, University of Pennsylvania

- Comic book universes explained simply

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.