- Attic Greek

-

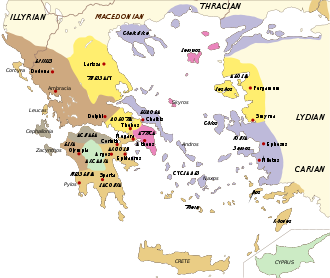

Distribution of Greek dialects in the classical period.[1]

Distribution of Greek dialects in the classical period.[1]

Western group: Central group: Eastern group: AtticAchaean Doric GreekHistory of the

Greek language

(see also: Greek alphabet)

Proto-Greek (c. 3000–1600 BC) Mycenaean (c. 1600–1100 BC) Ancient Greek (c. 800–330 BC)

Dialects:

Aeolic, Arcadocypriot, Attic-Ionic,

Doric, Locrian, Pamphylian,

Homeric Greek,

Macedonian (?)Koine Greek (c. 330 BC–330) Medieval Greek (330–1453) Modern Greek (from 1453)

Dialects:

Calabrian, Cappadocian, Cheimarriotika, Cretan,

Cypriot, Demotic, Griko, Katharevousa,

Pontic, Tsakonian, Maniot, Yevanic

*Dates (beginning with Ancient Greek) from Wallace, D. B. (1996). Greek Grammar Beyond the Basics: An Exegetical Syntax of the New Testament. Grand Rapids: Zondervan. p. 12. ISBN 0310218950.Attic Greek is the prestige dialect of Ancient Greek that was spoken in Attica, which includes Athens. Of the ancient dialects, it is the most similar to later Greek, and is the standard form of the language studied in courses of "Ancient Greek". It is sometimes included in Ionic.

Contents

Origin and range

Greek is a branch of the Indo-European language family, which includes English. In historical times, it already existed in several dialects (see article on Greek dialects), one of which was Attic.

The earliest written records in Greek date from the 16th to 11th centuries BC and exist in an archaic writing system, Linear B, belonging to the Mycenaean Greeks. The distinction between Eastern and Western Greek is believed to have arisen by Mycenaean times or before. Mycenaean Greek represents an early form of Eastern Greek, a main branching to which Attic also belongs. Because of the gap in the written record between the disappearance around 1200 BC of Linear B and the earliest inscriptions in the later Greek alphabet around 750 BC,[2] the further development of dialects remains opaque. Later Greek literature wrote of three main dialect divisions: Aeolic, Doric and Ionic. Attic was part of the Ionic dialect group. "Old Attic" is a term used for the dialect of Thucydides (460-400 BC) and the dramatists of Athens' remarkable 5th century; "New Attic" is used for the language of later writers.[3]

Attic Greek persisted until the 3rd century BC, when it was replaced by its similar but more universal offspring, Koine Greek, or "the Common Dialect" (ἡ κοινὴ διάλεκτος). The cultural dominance of the Athenian Empire and the later adoption of Attic Greek by king Philip II of Macedon (382-336 BC), father of the conqueror Alexander the Great, were the two keys that ensured the eventual victory of Attic over other Greek dialects and the spread of its descendant, Koine, throughout Alexander's Hellenic empire. The rise of Koine is conventionally marked by the accession in 285 BC of (Greek-speaking) Ptolemy II, who ruled from Alexandria, Egypt and launched the "Alexandrian period", when the city of Alexandria and its expatriate Greek-medium scholars flourished.[4]

In its day, the original range of the spoken Attic dialect included Attica, Euboea, some of the central Cyclades islands, and northern Aegean coastal areas of Thrace (i.e. Chalcidice). The closely related dialect called "Ionian" was spoken along the western and northwestern coasts of Asia Minor (modern Turkey) on the east side of the Aegean Sea. Eventually, literary Attic (and the classic texts written in it) came to be widely studied far beyond its original homeland, first in the Classical civilizations of the Mediterranean (Ancient Rome and the Hellenistic world), and later in the Muslim world, Europe, and wherever European civilization spread to other parts of the world.

Literature

The earliest recorded Greek literature, that attributed to Homer and dated to the 8th or 7th centuries BC, was not written in the Attic dialect, but in "Old Ionic". Athens and its dialect remained relatively obscure until its constitutional changes led to democracy in 594 BC, the start of the classical period and the rise of Athenian influence.

The first extensive works of literature in Attica are the plays of the dramatists Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides and Aristophanes in the 5th century BC. The military exploits of the Athenians led to some universally read and admired history, the works of Thucydides and Xenophon. Slightly less known because they are more technical and legal are the orations by Antiphon, Demosthenes, Lysias, Isocrates and many others. The Attic Greek of the philosopher Aristotle (384-322 BC), whose mentor was Plato, dates from the period of transition from Classical Attic to koine.

Students learning Ancient Greek today usually start with the Attic dialect, proceeding, depending on their interest, to the koine of the New Testament and other early Christian writings, or Homeric Greek to read the works of Homer and Hesiod, or Ionic Greek to read the histories of Herodotus and the medical texts of Hippocrates.

Alphabet

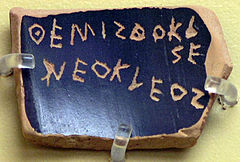

A ballot voting against Themistocles son of Neocles under the Athenian Democracy (see ostracism). Note the last two letters of Themistocles are written boustrophedon and E is used for both long and short e; that is, this is the epichoric alphabet.

A ballot voting against Themistocles son of Neocles under the Athenian Democracy (see ostracism). Note the last two letters of Themistocles are written boustrophedon and E is used for both long and short e; that is, this is the epichoric alphabet.

The classic Attic Alphabet is made up of the familiar 24 (capital) Greek letters: Α, Β, Γ, Δ, Ε, Ζ, Η, Θ, Ι, Κ, Λ, Μ, Ν, Ξ, Ο, Π, Ρ, Σ, Τ, Υ, Φ, Χ, Ψ, Ω.

It has seven vowels: Α, Ε, Η (long e), Ι, Ο, Υ, Ω (long o). The rest are consonants.

The first form of written Greek was not the Greek alphabet as it later became known, but the syllabary known as Linear B, in which one character stood for the combination of a consonant and a vowel.

The first use of what became the classic Greek alphabet remains unknown. By the time it was attested for in general use in the 8th century BC[5] it was already divided into a western and eastern variety, from which the Etruscan/Latin alphabets and the later Greek alphabet came respectively. What is today referred to as the Greek alphabet was originally the Phoenician alphabet borrowed to spell Greek words, with some originally Semitic consonantal letters – such as aleph (Greek Alpha = A), he (Greek Epsilon = E), and 'ayin (Greek Omicron = O) – used to represent Greek vowels. The creation of true vowel letters was the most revolutionary linguistic contribution of the Greeks to the development of the alphabet. (For the early forms of the letters, the full complement of letters, and the first inscriptions, see the article Greek alphabet.)

As the utility of an alphabet became evident, local varieties (sometimes called "epichoric"[6]) came into use. The early Attic alphabet still did not distinguish between long and short vowels (i.e. ε and η, ο and ω). It lacked the letters Ψ (psi) and Ξ (xi), using ΦΣ and ΧΣ instead. Lower case letters (α, β, γ, etc.) and iota subscript (a mediaeval invention) were still far in the future. Digamma (no longer in use in the Classical period) stood for a W.

Meanwhile in Ionia across the Aegean, a new Ionic form of the Attic alphabet was coming into being. It distinguished between long and short o (Ω and Ο) and stopped using Η (eta) to mark the rough breathing (i.e. H sound). Instead it created a sign for a long e with it, keeping the letter Ε for the short e. The digamma dropped out, and Ψ and Ξ came into existence, bringing the Attic alphabet to its classic 24-letter form. By 403 BCE, the by now internationally experienced city-state of Athens had perceived a need to standardize the alphabet, so it officially adopted the Ionic alphabet in that year. Many other cities had already adopted it.[citation needed]

When the ordinary citizen of Ancient Greece read inscriptions and the educated Greek read literature, what they saw was an all upper case Ionic alphabet: Α, Β, Γ, Δ, etc. By the time lower case letters, iota subscripts, accent marks, rough or smooth breathing marks over letters, and punctuation appeared in written Greek in the Middle Ages, Attic Greek writings had not been produced by native speakers for some centuries. Ancient Attic literature as published today thus makes use of a number of such non-ancient features. Uninformed modern readers might think that what they see on the page is the writing system exactly as the ancient Greeks used it in Classical Greece, but it is really Ancient Greek as transcribed by mediaeval Byzantine scribes.

Phonology

Vowels

Long a

Proto-Greek long ā → Attic long ē, but ā before e, i, r. ~ Ionic ē in all positions. ~ Doric and Aeolic ā in all positions.

- Proto-Greek and Doric mātēr → Attic mētēr "mother"

- Attic chōrā ~ Ionic chōrē "place", "country"

But Proto-Greek long ā → Attic ē after w (digamma), deleted by Classical Period.[7]

- Proto-Greek korwā[8] → early Attic-Ionic *korwē → Attic korē (Ionic kourē)

Short a

Proto-Greek short ă → Attic short ě. ~ Doric: short ă remains.

- Doric Artamis ~ Attic Artemis

Sonorant clusters

Compensatory lengthening of vowel before cluster of sonorant (r, l, n, m, w, sometimes y) and s, after deletion of s. ~ Aeolic: compensatory lengthening of sonorant.[9]

- Proto-Indo-European *es-mi (athematic verb) → Attic-Ionic ēmi (= εἰμί) ~ Aeolic emmi "I am"

Upsilon

Proto-Greek and other dialects' /u/ (English food) became Attic /y/ (pronounced as German ü, French u), represented by y in Latin transliteration of Greek names.

- Boeotian kourios ~ Attic kyrios "lord"

In the diphthongs eu and au, upsilon continued to be pronounced [u].

Long diphthongs

In the original long diphthongs with i, the i stopped being pronounced: āi, ēi, ōi → ā, ē, ō. The mediaeval iota subscript indicates this fact.

Contraction

Attic contracts more than Ionic. a + e → long ā.

- nika-e → nikā "conquer (thou)!"

e + e → ē (written ει: spurious diphthong)

- PIE *trey-es → Proto-Greek trehes → Attic trēs = τρεῖς "three"

e + o → ō (written ου: spurious diphthong)

- early *genes-os → Ionic geneos → Attic genous "of a kind" (genitive singular; Latin generis with r from rhotacism)

Vowel shortening

Attic ē (from long e-grade of ablaut or Proto-Greek ā) is sometimes shortened to e:

- when followed by a short vowel, with lengthening of the short vowel (quantitative metathesis): ēo → eō

- when followed by a long vowel: ēō → eō

- when followed by u and s: ēus → eus

- basilēos → basileōs "of a king" (genitive singular)

- basilēōn → basileōn (genitive plural)

- basilēusi → basileusi (dative plural)

Hyphaeresis

Attic deletes of one of two vowels in a row.

- Homeric boē-tho-os → Attic boēthos "running to a cry", "helper in battle"

Consonants

Palatalization

PIE *ky or *chy → Proto-Greek ts (palatalization) → Attic tt. — Ionic and Koine ss.

- Proto-Greek *glōkh-ya → Attic glōtta — Ionic glōssa "tongue"

Sometimes Proto-Greek *ty and *tw → Attic tt. — Ionic and Koine ss.

- PIE *kwetwores → Attic tettares — Ionic tesseres "four" (Latin quattuor)

Proto-Greek and Doric t before i or y → Attic-Ionic s (palatalization).

- Doric ti-the-nti → Attic tithēsi = τίθεισι "he places" (compensatory lengthening of e → ē = spurious diphthong ει)

Shortening of ss

Early Attic-Ionic ss → Classical Attic s.

- PIE *medh-yos → Homeric messos (palatalization) → Attic mesos "middle"

Loss of w

Proto-Greek w (digamma) was lost in Attic before historical times.

- Proto-Greek korwā[11] → Attic korē "girl"

Retention of h

Attic retained Proto-Greek h- (from Proto-Indo-European initial s- or y-), but certain other dialects lost it (psilosis "stripping", "de-aspiration").

- Proto-Indo-European *si-sta-mes → Attic histamen — Cretan istamen "we stand"

Movable n

Attic-Ionic places an n (movable nu) at the end of some words that would ordinarily end in a vowel, when the next word starts with a vowel, to prevent hiatus (two vowels in a row).

- pāsin élegon "they spoke to everyone" vs. pāsi legousi

- pāsi(n) dative plural of "all"

- legousi(n) "they speak" (3rd person plural, present indicative active)

- elege(n) "he was speaking" (3rd person singular, imperfect indicative active)

- titheisi(n) "he places", "makes" (3rd person singular, present indicative active: athematic verb)

Morphology

Morphology as used here means "word formation." It can also include inflection, the formation of the forms of declension or conjugation by suffixing endings, but that topic is presented under Ancient Greek grammar.

- Attic tends to replace the -ter "doer of" suffix with -tes: dikastes for dikaster "judge".

- The Attic adjectival ending -eios and corresponding noun ending, both two-syllable with the diphthong ei, stand in place of ēios, with three syllables, in other dialects: politeia, Cretan politēia, "constitution", both from politewia, where the w drops out.

Grammar

Attic Greek grammar is to a large extent ancient Greek grammar, or at least when the latter topic is presented it is with the peculiarities of the Attic dialect. This section only mentions some of the Attic peculiarities.

Number

In addition to singular and plural numbers, Attic Greek had the dual number. This was used if only two nouns were involved and was present as inflection in noun, adjectives, pronouns and verbs (any categories inflected for number). Attic Greek was the last dialect to retain this from older forms of Greek and the dual number had died out by the end of the fifth century before Christ.

Declension

With regard to declension, the stem is the part of the declined word to which case endings are suffixed. In the a-, alpha- or first declension feminines, the stem ends in long a, parallel to the Latin first declesion. In Attic-Ionic the stem vowel has changed to long e (eta) in the singular, except (in Attic only) after e, i, r: gnome, gnomes, gnome(i), gnomen, etc., "opinion", but thea, theas, thea(i), thean, etc., "goddess."

The plural is the same in both cases: gnomai and theai, but other sound changes were more important in its formation. For example, original -as in the nominative plural was replaced by the diphthong, -ai, which did not undergo the change of a to e. In the few a-stem masculines, the genitive singular follows the o-declension: stratiotēs, stratiotou, stratiotēi, etc.

In the o-, omicron- or second declension, mainly masculines (but some feminines), the stem ends in o or e, which is composed in turn of a root plus the thematic vowel, an o or e in Indo-European ablaut series parallel to similar formations of the verb. It is the equivalent of the Latin second declension. The alternation of Greek -os and Latin -us in the nominative singular is familiar to readers of Greek and Latin.

In Attic Greek an original genitive singular ending *-osyo after losing the s (as happens in all the dialects) lengthens the stem o to the spurious diphthong -ou (see above under Phonology, Vowels): logos "the word", logou from *logosyo, "of the word". The dative plural of Attic-Ionic had -oisi, which appears in early Attic but simplifies to -ois in later": anthropois "to or for the men".

Classical Attic

See also Classical Athens and Classical Latin

Classical Attic may refer either to the varieties of Attic Greek spoken, and written in Greek majuscule[12] during the 5th and 4th centuries BC (Classical-era Attic) or to the Hellenistic and Roman[13] era standardized Attic Greek, mainly on the language of Attic orators, and written in Greek uncial (good Attic and vehement rival of vulgar or Koine Greek)

Varieties

The varieties of Classical-era Attic are:

- The vernacular and poetic dialect of Aristophanes

- The dialect of Thucydides (mixed Old Attic with neologisms)

- The dialect and orthography of Old Attic inscriptions in Attic alphabet before 403 BC (Ionic alphabet-reform by archon Eucleides). Thucydidean orthography, albeit transmitted, is close to them.

- The conventionalized and poetic dialect of the Attic tragic poets, mixed with Epic and Ionic Greek and used in the episodes. (In the choral odes conventional Doric is used).

- Formal Attic of Attic orators, Plato,[14] Xenophon and Aristotle, imitated by the Atticists or Neo-Attic writers. It is considered good or standard Attic.

See also

- Ancient Greek

- Ancient Greek dialects

- Ancient Greek grammar

- Ancient Greek phonology

- Attic numerals

- Greek Alphabet

- Greek language

Notes

- ^ Roger D. Woodard (2008), "Greek dialects", in: The Ancient Languages of Europe, ed. R. D. Woodard, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 51.

- ^ See the summary by Susan Shelmerdine, Greek Alphabet, the section in the Indo-European Database on the Greek Alphabet and the ancientscripts.com site

- ^ From Goodwin and Gulick's classic text "Greek Grammar" (1930)

- ^ Goodwin and Gulick in "Greek Grammar"

- ^ The Encyclopedia Britannica mentions the Dipylon vase from Athens as the first, giving a date of 725

- ^ Buck, Greek Dialects, uses this term.

- ^ Smyth, par. 30 and note, 31: long a in Attic and dialects

- ^ Liddell and Scott, κόρη.

- ^ Paul Kiparsky, "Sonorant Clusters in Greek" (Language, Vol. 43, No. 3, Part 1, pp. 619-635: Sep. 1967) on JSTOR.

- ^ V = vowel, R = sonorant, s is itself. VV = long vowel, RR = doubled or long sonorant.

- ^ Liddell and Scott, κόρη.

- ^ Only the excavated inscriptions of the era. The Classical Attic works are transmitted in uncial manuscripts

- ^ Including the Byzantine Atticists

- ^ Platonic style is poetic

References

- Goodwin, William W. (1879). Greek Grammar. Macmillan Education. ISBN 0-89241-118-X.

- Smyth, Herbert Weir (1920). Greek Grammar. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-36250-0.

- Buck, Carl Darling (1955). The Greek Dialects. The University of Chicago Press.

External links

- Greek Grammar on the Web

- Ancient Greek Tutorials - provides attic Greek audio pronunciations of letters and words

- Smyth's Greek Grammar

- Classical (Attic) Greek Online

Ancient Greece Periods Geography Politics Rulers - Kings of Sparta

- Kings of Athens

- Archons of Athens

- Kings of Macedon

- Kings of Pontus

- Kings of Paionia

- Roman Emperors

- Kings of Kommagene

- Kings of Lydia

- Attalid Kings of Pergamon

- Diadochi

- Kings of Argos

- Tyrants of Syracuse

Life - Agriculture

- Clothing

- Cuisine

- Democracy

- Economy

- Education

- Festivals

- Homosexuality

- Law

- Marriage

- Mourning ritual

- Olympic Games

- Pederasty

- Philosophy

- Prostitution

- Religion

- Slavery

- Warfare

- Wine

Military - Wars

- Army of Macedon

- Antigonid Macedonian army

- Pezhetairoi

- Hoplite

- Seleucid army

- Hellenistic armies

- Phalanx formation

- Peltast

- Sarissa

- Xyston

- Sacred Band of Thebes

People OthersGroups- Playwrights

- Poets

- Philosophers

- Tyrants

- Mythological figures

CulturesBuildings Arts Sciences Language Writing Lists - Cities in Epirus

- Theatres

- Cities

- Place names

Greek language · Eλληνική γλώσσα History Proto-Greek (c. 3000–1600 BC) · Mycenaean (c. 1600–1000 BC) · Ancient Greek (c. 1000–330 BC) · Koine Greek (c. 330 BC–330) · Medieval Greek (330–1453) · Modern Greek (from 1453)

Alphabet Letters Phonology Grammar Dialects Cappadocian · Cretan · Cypriot · Chalkidiki · Demotic · Greek-Calabrian · Griko · Katharevousa · Macedonian · Misthiotica · Pontic · Tsakonian · YevanicLiterature Related Topics Promotion and Study Ages of Greek c. 3rd millenium BC c. 1600–1100 BC c. 800–300 BC c. 300 BC – AD 330 c. 330–1453 since 1453 Categories:- Ancient Greek language

- Varieties of Ancient Greek

- Classical languages

- Ancient languages

- Languages of ancient Macedonia

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.