- Balloon (aircraft)

-

"Ballooning" redirects here. For the behavior of spiders and other arthropods, see Ballooning (spider).

Balloon Part of a series on

Categories of aircraftSupported by lighter-than-air gases (aerostats) Unpowered Powered - Balloon

Supported by LTA gases + aerodynamic lift Unpowered Powered - Hybrid moored balloon

- Kytoon

Supported by aerodynamic lift (aerodynes) Unpowered Powered Unpowered fixed-wing Powered fixed-wing - Glider

- Hang gliders

- Paraglider

- Kite

- Airplane (aeroplane)

- Powered paraglider

- Flettner airplane

- Ground-effect vehicle

Powered hybrid fixed/rotary wing Unpowered rotary-wing Powered rotary-wing - Autogyro

- Gyrodyne ("Heliplane")

- Helicopter

Powered aircraft driven by flapping Other means of lift Unpowered Powered A balloon is a type of aircraft that remains aloft due to its buoyancy. A balloon travels by moving with the wind. It is distinct from an airship, which is a buoyant aircraft that can be propelled through the air in a controlled manner.

The "basket" or capsule that is suspended by cables beneath a balloon and carries people, animals, or automatic equipment (including cameras and telescopes, and flight-control mechanisms) may also be called the gondola.

Contents

Types

There are three main types of balloon aircraft:

- Hot air balloons obtain their buoyancy by heating the air inside the balloon. They are the most common type of balloon aircraft. "Hot air balloon" is sometimes used incorrectly to denote any balloon that carries people.

- Gas balloons are inflated with a gas of lower molecular weight than the ambient atmosphere. Most gas balloons operate with the internal pressure of the gas being the same as the pressure of the surrounding atmosphere. There is a type of gas balloon, called a superpressure balloon, that can operate with the lifting gas at pressure that exceeds the pressure of the surrounding air, with the objective of limiting or eliminating the loss of gas from day-time heating. Gas balloons are filled with gases such as:

- hydrogen - not widely used for aircraft since the Hindenburg disaster because of high flammability (except for some sport balloons as well as nearly all unmanned scientific and weather balloons).

- helium - the gas used today for all airships and most manned balloons.

- ammonia - used infrequently due to its caustic qualities and limited lift.

- coal gas - used in the early days of ballooning; it is highly flammable.

- methane - used as a lower cost lifting gas, but offering less lift than helium or hydrogen.[1]

- Rozière balloons use both heated and unheated lifting gases. The most common modern use of this type of balloon is for long-distance record flights such as the recent circumnavigations.

History

Unmanned hot air balloons are popular in Chinese history. Zhuge Liang of the Shu Han kingdom, in the Three Kingdoms era (220-280 AD) used airborne lanterns for military signaling. These lanterns are known as Kongming lanterns (孔明灯).[2][3]

There is also some speculation, from a demonstration led by British modern hot air balloonist Julian Nott in the late 1970s[4] and again in 2003,[5] that hot air balloons could have been used by people of the Nazca culture of Peru some 1500 to 2000 years ago, as a tool for designing the famous Nazca ground figures and lines.[4]

In 1709 Brazilian cleric Bartolomeu de Gusmão made a balloon filled with heated air rise inside a room in Lisbon. He also built a balloon named Passarola (English: Big bird) and attempted to lift himself from Saint George Castle in Lisbon, but only managed to harmlessly fall about one kilometre away.[6][7][8][9][10][11] This claim is not generally recognized by aviation historians outside the Portuguese speaking community, in particular the FAI.[12][13]

Following Henry Cavendish's 1766 work on hydrogen, Joseph Black proposed that a balloon filled with hydrogen would be able to rise in the air.

The first recorded manned flight was made in a hot air balloon built by the Montgolfier brothers on November 21, 1783.[12][14] The flight started in Paris and reached a height of 500 feet or so. The pilots, Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier and François Laurent d'Arlandes, covered about 5½ miles in 25 minutes.

Only a few days later, on December 1, 1783, Professor Jacques Charles and Nicholas Louis Robert made the first gas balloon flight, also from Paris. Their hydrogen-filled balloon flew to almost 2,000 feet (600 m), stayed aloft for over 2 hours and covered a distance of 27 miles (43 km), landing in the small town of Nesles-la-Vallée.

The first aircraft disaster occurred in May 1785 when the town of Tullamore, County Offaly, Ireland was seriously damaged when the crash of a balloon resulted in a fire that burned down about 100 houses, making the town home to the world's first aviation disaster. To this day, the town shield depicts a phoenix rising from the ashes.

Balloon landing in Mashgh square, Iran (Persia), at the time of Nasser al-Din Shah Qajar, around 1850.

Balloon landing in Mashgh square, Iran (Persia), at the time of Nasser al-Din Shah Qajar, around 1850.

Jean-Pierre Blanchard went on to make the first manned flight of a balloon in America on January 9, 1793, after touring Europe to set the record for the first balloon flight in countries including Belgium, Germany, the Netherlands and Poland. His hydrogen filled balloon took off from a prison yard in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The flight reached 5,800 feet (1,770 m) and landed in Gloucester County, New Jersey. President George Washington was among the guests observing the takeoff.

On September 29, 1804, Abraham Hopman became the first Dutchman to make a successful balloon flight in the Netherlands.[15]

Gas balloons became the most common type from the 1790s until the 1960s. The French military observation balloon L'Intrépide of 1795 is the oldest preserved aircraft in Europe; it is on display in the Heeresgeschichtliches Museum in Vienna.

The first steerable balloon (also known as a dirigible) was flown by Henri Giffard in 1852. Powered by a steam engine, it was too slow to be effective. As it did with heavier-than-air flight, the internal combustion engine made dirigibles – especially blimps – practical, starting in the late 19th century. In 1857 balloonist American John Steiner attempted an ambitious flight across Lake Erie:[16]

“ He arose to the height of about three miles, and started off at a slow but steady rate ... The lake could be seen from one end to the other nearly ... At one time Mr. Steiner counted 38 sail vessels, all in sight, and far below him. The hands on board several of the vessels saw him, and rightly apprehending that he was an aeronaut, cheered him heartily ... He neared the Canada shore a little below Long Point ... he was accordingly driven towards Buffalo ... Night was drawing on and it became apparent that he could not, with this current, get away from the water before dark, and after nightfall it would not be safe to come down. Seeing a propeller ... the Mary Stewart ... He first struck the water about 25 miles below Long Point ... During this time Mr. Steiner says he thinks his balloon bounded from the water at least twenty times. It would strike and then rebound, like a ball, going into the air from twenty to fifty feet, and still rushing down the lake at railroad speed ... Mr. Steiner then abandoned the balloon, leaping into the water and swimming towards the boat, which speedily reached him... -- New York Times, July 23, 1857[16] ” In 1872 Paul Haenlein flew the first (tethered) internal combustion motor powered balloon. The first to fly in an untethered airship powered by an internal combustion engine was Alberto Santos Dumont in 1898.

Henri Giffardalso developed a tethered balloon for passengers in 1878 in the Tuileries Garden in Paris. The first tethered balloon in modern times was made in France at Chantilly Castle in 1994 by Aerophile SA.

Ed Yost redesigned the hot air balloon in the late 1950s using rip-stop nylon fabrics and high-powered propane burners to create the modern hot air balloon. His first flight of such a balloon, lasting 25 minutes and covering 3 miles (5 km), occurred on October 22, 1960 in Bruning, Nebraska. Yost's improved design for hot air balloons triggered the modern sport balloon movement. Today, hot air balloons are much more common than gas balloons.

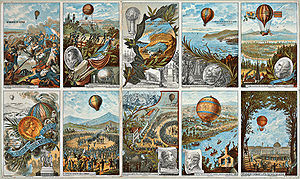

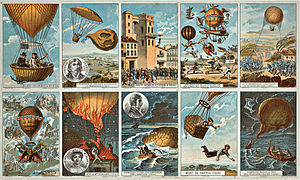

Events in the early history of ballooning; collecting cards from the late 19th century. As flying machines

A balloon is conceptually the simplest of all flying machines. The balloon is a fabric envelope filled with a gas that is lighter than the surrounding atmosphere. As the entire balloon is less dense than its surroundings, it rises, taking along with it a basket, attached underneath, that carries passengers or payload. Although a balloon has no propulsion system, a degree of directional control is possible through making the balloon rise or sink in altitude to find favorable wind directions.

The first balloons capable of carrying passengers used hot air to obtain buoyancy and were built by the brothers Josef and Etienne Montgolfier in Annonay, France.

Balloons using the light gas hydrogen for buoyancy were flown less than a month later. They were invented by Professor Jacques Charles and first flown on December 1, 1783. Gas balloons have greater lift and can be flown much longer than hot air, so gas balloons dominated ballooning for the next 200 years. In the 19th century, it was common to use town gas to fill balloons; it was not as light as pure hydrogen gas, but was much cheaper and readily available.

The third balloon type was invented by Pilâtre de Rozier and is a hybrid of a hot air and a gas balloon. Gas balloons have an advantage of being able to fly for a long time, and hot air balloons have an advantage of being able to easily change altitude, so the Rozier balloon was a hydrogen balloon with a separate hot air balloon attached. In 1785, Pilâtre de Rozier took off in an attempt to fly across the English Channel, but the balloon exploded a half-hour into the flight. This accident earned de Rozier the title "The First to Fly and the First to Die". It wasn't until the 1980s that technology once again allowed the Rozier balloons to become feasible.

Both the hot air, or Montgolfière, balloon and the gas balloon are still in common use. Montgolfière balloons are relatively inexpensive as they do not require high-grade materials for their envelopes, and they are popular for balloonist sport activity.

In addition to free flight, a balloon may be tethered to allow reliable take off and landing at the same location. This can be done with hot air and gas balloon. Tethered gas balloons have been installed as amusement rides in Paris since 1999, in Berlin since 2000, in Disneyland Resort Paris since 2005, in the San Diego Wild Animal Park since 2005, in Walt Disney World in Orlando since 2009, and the DHL Balloon in Singapore since 2006. Modern tethered gas balloons are made by Aerophile SA.

Light gas balloons are predominant in scientific applications, as they are capable of reaching much higher altitudes for much longer periods of time. They are generally filled with helium. Although hydrogen has more lifting power, it is explosive in an atmosphere rich in oxygen. With a few exceptions, scientific balloon missions are unmanned.

There are two types of light-gas balloons: zero-pressure and superpressure. Zero-pressure balloons are the traditional form of light-gas balloon. They are partially inflated with the light gas before launch, with the gas pressure the same both inside and outside the balloon. As the zero-pressure balloon rises, its gas expands to maintain the zero pressure difference, and the balloon's envelope swells.

At night, the gas in a zero-pressure balloon cools and contracts, causing the balloon to sink. A zero-pressure balloon can only maintain altitude by releasing gas when it goes too high, where the expanding gas can threaten to rupture the envelope, or releasing ballast when it sinks too low. Loss of gas and ballast limits the endurance of zero-pressure balloons to a few days.

A superpressure balloon, in contrast, has a tough and inelastic envelope that is filled with light gas to pressure higher than that of the external atmosphere, and then sealed. The superpressure balloon cannot change size greatly, and so maintains a generally constant volume. The superpressure balloon maintains an altitude of constant density in the atmosphere, and can maintain flight until gas leakage gradually brings it down.[17]

Superpressure balloons offer flight endurance of months, rather than days. In fact, in typical operation an Earth-based superpressure balloon mission is ended by a command from ground control to open the envelope, rather than by natural leakage of gas.

For air transport balloons must contain a gas lighter than the surrounding air. There are two types:

- Hot air balloon: filled with hot air, which by heating becomes lighter than the surrounding air; they have been used to carry human passengers since the 1790s;

- Balloons filled with:

- hydrogen - highly flammable (see Hindenburg disaster)

- helium - safe if used properly, but very expensive.

Large helium balloons are used as high flying vessels to carry scientific instruments (as do weather balloons), or even human passengers with a tether like in İstanbul, Paris, Berlin, Hong Kong or Singapore.

Cluster ballooning uses many smaller gas-filled balloons for flight (see An Introduction to Cluster Ballooning).

Military use

The first military use of a balloon was at the Battle of Fleurus in 1794, when L'Entreprenant was used by the French Aerostatic Corps to watch the movements of the enemy. On April 2, 1794, an aeronauts corps was created in the French army; however, given the logistical problems linked with the production of hydrogen on the battlefield (it required constructing ovens and pouring water on white-hot iron), the corps was disbanded in 1799.

American Civil War

The first major-scale use of balloons in the military occurred during the American Civil War with the Union Army Balloon Corps established and organized by Prof. Thaddeus S. C. Lowe in the summer of 1861. Originally, the balloons were inflated with coal gas from municipal services and then walked out to the battlefield, an arduous and inefficient operation as the balloons had to be returned to the city every four days for re-inflation. Eventually hydrogen gas generators, a compact system of tanks and copper plumbing, were constructed which converted the combining of iron filings and sulfuric acid to hydrogen. The generators were easily transported with the uninflated balloons to the field on a standard buckboard. However, this method shortened the life of the balloons, because traces of the sulfuric acid often entered the balloons along with the hydrogen.[18] In all, Lowe built seven balloons that were fit for military service.

The first application thought useful for balloons was map-making from aerial vantage points, thus Lowe's first assignment was with the Topographical Engineers. General Irvin McDowell, commander of the Army of the Potomac, realized their value in aerial reconnaissance and had Lowe, who at the time was using his personal balloon the Enterprise, called up to the First Battle of Bull Run. Lowe also worked as a Forward Artillery Observer (FAO) by directing artillery fire via flag signals. This enabled gunners on the ground to fire accurately at targets they could not see, a military first.

Lowe's first military balloon, the Eagle was ready by October 1, 1861. It was called into service immediately to be towed to Lewinsville, Virginia, without any gas generator which took longer to build. The trip began after inflation in Washington, D.C. and turned into a 12 mile (19 km), 12-hour excursion that was upended by a gale force wind which ripped the aerostat from its netting and sent it sailing to the coast. Balloon activities were suspended until all balloons and gas generators were completed.

With his ability to inflate balloons from remote stations, Lowe, his new balloon the Washington and two gas generators were loaded onto a converted coal barge the George Washington Parke Custis. As he was towed down the Potomac, Lowe was able to ascend and observe the battlefield as it moved inward on the heavily forested peninsula. This would be the military's first claim of an aircraft carrier.

The Union Army Balloon Corps enjoyed more success in the battles of the Peninsula Campaign than the Army of the Potomac it sought to support. The general military attitude toward the use of balloons deteriorated, and by August 1863 the Balloon Corps was disbanded.

The Confederate Army also made use of balloons, but they were gravely hampered by supplies due to the embargoes. They were forced to fashion their balloons from colored silk dress-making material, and their use was limited by the infrequent supply of gas in Richmond, Virginia. By the summer of 1863, all balloon reconnaissance of the Civil War had ceased.

After the American Civil War

Close-up view of an American major in the basket of an observation balloon flying over territory near front lines during World War I.

In Britain during July 1863, experimental balloon ascents for reconnaissance purposes were conducted by the Royal Engineers on behalf of the British Army, but although the experiments were successful it was considered not worth pursuing further because it was too expensive. However by 1888 a School of Ballooning was established at Chatham, Medway, Kent.

During the Paraguayan War of the Triple Alliance (1864–70), balloons were also used for observation by the Brazilian Army.

Balloons were used by the Royal Engineers for reconnaissance and observation purposes during the Bechuanaland Expedition (1885), the Sudan Expedition (1885) and during the Anglo-Boer War (1899–1902). A 11,500 cubic feet (330 m3) balloon was kept inflated for 22 days and marched 165 miles into the Transvaal with the British forces.[19]

Hydrogen-filled balloons were also widely used during World War I (1914–1918) to detect enemy troop movements and to direct artillery fire. Observers phoned their reports to officers on the ground who then relayed the information to those who needed it. Balloons were frequently targets of opposing aircraft. Planes assigned to attack enemy balloons were often equipped with incendiary bullets, for the purpose of igniting the hydrogen.

The Aeronaut Badge was established by the United States Army in World War I to denote service members who were qualified balloon pilots. Observation balloons were retained well after the Great War, being used in the Russo-Finnish Wars, the Winter War of 1939-40, and the Continuation War of 1941-45.

During World War II the Japanese launched thousands of helium "fire balloons" against the United States and Canada. In Operation Outward the British used balloons to carry incendiaries to Nazi Germany.

Large helium balloons are used by the South Korean government and private activists advocating freedom in North Korea. They float hundreds of kilometers across the border carrying news from the outside world, illegal radios, foreign currency and gifts of personal hygiene supplies. A North Korean military official has described it as "psychological warfare" and threatened to attack South Korea if their release continued.[20][21]

Records

On May 27, 1931, Auguste Piccard and Paul Kipfer became the first to reach the stratosphere in a balloon.[22]

On March 1, 1999 Bertrand Piccard and Brian Jones set off in the balloon Breitling Orbiter 3 from Château d'Oex in Switzerland on the first non-stop balloon circumnavigation around the globe. They landed in Egypt after a 45,755 kilometers flight lasting 19 days, 21 hours and 47 minutes (95.77 km/h / 59.47 mph).

On August 31, 1933, Alexander Dahl took the first picture of the Earth's curvature in an open hydrogen gas balloon.

The altitude record for a manned balloon was set at 34,668 meters (113,739 ft) on May 4, 1961 by Malcolm Ross and Victor Prather in the Stratolab V balloon payload launched from the deck of the USS Antietam in the Gulf of Mexico.

The altitude record for an unmanned balloon is 53.0 kilometres (173,882 ft), reached with a volume of 60,000 cubic metres. The balloon was launched by JAXA on May 25, 2002 from Iwate Prefecture, Japan.[23] This is the greatest height ever obtained by an atmospheric vehicle. Only rockets, rocket planes, and ballistic projectiles have flown higher.

In space

The Echo satellite was a balloon launched into Earth orbit in 1960 and used for passive relay of radio communication. PAGEOS was another "satelloon" launched in 1966 for worldwide satellite triangulation, allowing for greater precision in the calculation of different locations on the planet's surface.

In 1984 the Soviet space probes Vega 1 and Vega 2 released two balloons with scientific experiments in the atmosphere of Venus. They transmitted signals for two days to Earth.

In literature

Jules Verne wrote a non fiction story about being stranded in a hydrogen balloon, see [24]

Sports

See also

- Balloon Flight Contest

- Balloon-carried light effect

- Blimp

- Cluster ballooning

- First flying machine

- Gas balloon

- High-altitude balloon

- Hopper balloon

- Hot air balloon

- Hot air ballooning

- Lane hydrogen producer

- List of altitude records reached by different aircraft types

- List of civil aviation authorities

- List of early flying machines

- List of firsts in aviation

- Observation balloon

References

- ^ "Balloon Lift with Lighter than Air Gases: Methane". UH Manoa Chemistry Department. http://www.chem.hawaii.edu/uham/lift.html. Retrieved 2010-05-24.

- ^ Ancient Chinese Inventions

- ^ The Ten Thousand Infallible Arts of the Prince of Huai-Nan

- ^ a b "The Extraordinary Nazca Prehistoric Balloon". Julian Nott. http://www.nott.com/Pages/projects.php. Retrieved 2011-10-15.

- ^ Julian Nott (March/April 2003). "History Revisited: Julian Nott Reprises his Flight over the Plains of Nazca". Ballooning. http://www.nott.com/Pages/Nazca_BFA-1.pdf. Retrieved 2011-10-15.

- ^ AMEIDA, L. Ferrand de, "Gusmão, Bartolomeu Lourenço de", in SERRÃO, Joel, Dicionário de História de Portugal, Porto, Figueirinhas, 1981, vol. III, pp. 184–185

- ^ CARVALHO, História dos Balões, Lisboa, Relógio d'Agua, 1991

- ^ CRUZ FILHO, F. Murillo, Bartolomeu Lourenço de Gusmão: Sua Obra e o Significado Fáustico de Sua Vida, Rio de Janeiro, Biblioteca Reprográfica Xerox, 1985

- ^ SILVA, Inocencio da, ARANHA, Brito, Diccionario Bibliographico Portuguez, Lisboa, Imprensa Nacional, T. I, pp. 332–334

- ^ TAUNAY, Affonso d'Escragnolle, Bartolomeu de Gusmão: inventor do aerostato: a vida e a obra do primeiro inventor americano, S. Paulo, Leia, 1942

- ^ TAUNAY, Affonso d'Escragnolle, Bartholomeu de Gusmão e a sua prioridade aerostatica, S. Paulo: Escolas Profissionaes Salesianas, 1935, Sep. do Annuario da Escola Polytechnica da Univ. de São Paulo, 1935

- ^ a b "FAI Ballooning Commission Achievements". Fédération Aéronautique Internationale. http://www.fai.org/ballooning/achieve.asp. Retrieved 2010-04-11. "A list of notable balloon and airship flights has been assembled by Hans Åkerstedt from Sweden. The list has been compiled with much help from Troy Bradley, USA and Norman Pritchard, UK. Information from many other sources have also been used - FAI record files, personal log books and commercially available literature."

- ^ "CIA Notable flights and performances: Part 01, 0000-1785". Svenska Ballong Federationen. http://www.ballong.org/notable/rpt00.php?num=01&period=0000-1785. Retrieved 2010-04-11. "Date 1709-08-08 Pilot: Bartholomeu Lourenço de Gusmão, Earliest recorded model balloon flight."

- ^ "CIA Notable flights and performances: Part 01, 0000-1785". Svenska Ballong Federationen. http://www.ballong.org/notable/rpt00.php?num=01&period=0000-1785. Retrieved 2010-04-11. "Date 1783-11-21 Pilot: Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier, First recorded manned flight."

- ^ Nabben, Han (2011). Lichter dan Lucht, los van de aarde. Barneveld, Netherlands: BDU Boeken. ISBN 978-90-8788-151-1. http://ballonboek.nl. Retrieved 2011-11-12.

- ^ a b "Perilous Balloon Ascension--The Eronaut in Lake Erie.". The New York Times. July 23, 1857. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=9A0CEFD91238EE3BBC4B51DFB066838C649FDE. Retrieved 2010-01-25.

- ^ "Successful Flight Of NASA Prototype Super-Pressure Balloon In Antarctica". Space-travel.com. http://www.space-travel.com/reports/Successful_Flight_Of_NASA_Prototype_Super_Pressure_Balloon_In_Antarctica_999.html. Retrieved 2011-06-18.

- ^ "Encyclopedia of War Machines" edited by Daniel Bowen.

- ^ Bruce, Eric Stuart (1914). Aircraft in war. London: Hodder and Stoughton. p. 8. http://www.archive.org/stream/aircraftinwar00brucuoft#page/8/mode/1up. Retrieved 2009-11-04.

- ^ "Balloon launches breach North Korea's bubble - science-in-society - 01 March 2011". New Scientist. http://www.newscientist.com/article/dn20180-balloon-launches-breach-north-koreas-bubble.html. Retrieved 2011-06-18.

- ^ "Helium balloons float propaganda into North Korea". Articles.cnn.com. 2010-05-31. http://articles.cnn.com/2010-05-31/world/south.korea.message_1_north-koreans-defectors-south-korean-warship. Retrieved 2011-06-18.

- ^ Tripod

- ^ Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency. "Research on Balloons to Float Over 50km Altitude". Isas.jaxa.jp. http://www.isas.jaxa.jp/e/special/2003/yamagami/. Retrieved 2011-06-18.

- ^ "A Voyage in a Balloon by Jules Verne - Free eBook". Manybooks.net. 2005-06-18. http://manybooks.net/titles/vernejul16081608516085-8.html. Retrieved 2011-06-18.

External links

- The Early Years of Sport Ballooning

- Hot Air Balloon Simulator - learn the dynamics of a hot air balloon on the Internet based simulator.

- Stratocat Historical recompilation project on the use of stratospheric balloons in the scientific research, the military field and the aerospace activity

- Royal Engineers Museum Royal Engineers and Aeronautics

- Royal Engineers Museum Early British Military Ballooning (1863)

- Balloon fabrics made of Goldbeater's skins by Chollet, L. Technical Section of Aeronautics. December 1922

- Tripod

Categories:- Balloons (aircraft)

- Ballooning

- Airship technology

- Hydrogen technologies

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.