- Chiang Ching-kuo

-

Chiang Ching-kuo

蔣經國

6th/7th-term President of the Republic of China In office

20 May 1978 – 13 January 1988Vice President Hsieh Tung-min

Lee Teng-huiPreceded by Yen Chia-kan Succeeded by Lee Teng-hui 21st Premier of the Republic of China In office

29 May 1972 – 20 May 1978President Chiang Kai-shek

Yen Chia-kanPreceded by Yen Chia-kan Succeeded by Sun Yun-suan 1st Chairman of the Kuomintang In office

5 April 1975 – 13 January 1988Preceded by Chiang Kai-shek (Director-General of the Kuomintang) Succeeded by Lee Teng-hui Personal details Born 27 April 1910

Fenghua, Zhejiang, Qing EmpireDied 13 January 1988 (aged 77)

Taipei, Republic of ChinaNationality Chinese Political party Kuomintang Spouse(s) Chiang Fang-liang (m.1935-1988) Children Chiang Hsiao-wen

(1935-1989)

Chiang Hsiao-chang

(1936-)

Chang Hsiao-tzu

(1941-1996)

Chiang Hsiao-yen

(1941-)

Chiang Hsiao-wu

(1945-1991)

Chiang Hsiao-yung

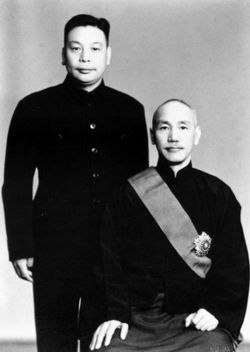

(1948-1996)Alma mater Moscow Sun Yat-sen University Occupation Politician Religion Methodist[1] Chiang Ching-kuo Traditional Chinese 蔣經國 Simplified Chinese 蒋经国 Transcriptions Mandarin - Hanyu Pinyin Jiǎng Jīngguó - Wade–Giles Chiang Ching-kuo Min - Hokkien POJ ChiúⁿKeng-kok Wu - Romanization [tɕiã.tɕiŋ.koʔ] Chiang Ching-kuo (traditional Chinese: 蔣經國; simplified Chinese: 蒋经国; pinyin: Jiǎng Jīngguó; Wade–Giles: Chiang Ching-kuo; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Chiúⁿ Keng-kok; Shanghai/Ningbo dialect: [tɕiã.tɕiŋ.koʔ]) (April 27,1 1910 – January 13, 1988), Kuomintang (KMT) politician and leader, was the son of President Chiang Kai-shek and held numerous posts in the government of the Republic of China (ROC). He succeeded his father to serve as Premier of the Republic of China between 1972 and 1978, and was the 6th and 7th-term President of the Republic of China from 1978 until his death in 1988. Under his tenure, the government of the Republic of China, while authoritarian, became more open and tolerant of political dissent. Towards the end of his life, Chiang relaxed government controls on the media and speech and allowed native Taiwanese into positions of power, including his successor Lee Teng-hui.

Contents

Early life

The son of President Chiang Kai-shek and his first wife Mao Fumei, Chiang Ching-kuo was born in Fenghua, Zhejiang, with the courtesy name of Jiànfēng (建豐). He had an adopted brother, Chiang Wei-kuo. "Ching" literally means "longitude" while "kuo" means "nation"; in his brother's name, "wei" literally means "parallel (of latitude)". The names are inspired by the references in Chinese classics such as the Guoyu, in which "to draw the longitudes and latitudes of the world" is used as a metaphor for a person with great abilities, especially in managing a country.

While the young Chiang Ching-kuo had a peaceable relationship with his mother and grandmother (who were deeply rooted to their Buddhist faith), his relationship with his father was strict, utilitarian and often rocky. Chiang Kai-shek appeared to his son as an authoritarian figure, sometimes indifferent to his problems. Even in personal letters between the two, Chiang Kai-shek would sternly order his son to improve his Chinese calligraphy.

From 1916 until 1919 Chiang Ching-kuo attended the "Grammar School" in Wushan in Hsikou. Then, in 1920, his father hired tutors to teach him the four books, considered the basis of all Chinese culture. On June 4, 1921, Ching-kuo's grandmother died. What might have been an immense emotional loss was compensated for by Chiang Kai-shek moving his family to Shanghai. Chiang Ching-Kuo's stepmother, historically known as the Chiang family's "Shanghai Mother", went with them. During this period, Chiang Kai-shek concluded that Chiang Ching-kuo was a son to be taught, while Chiang Wei-Kuo was a son to be loved.

During his time in Shanghai, Ching-kuo was supervised by his father by being made to write a weekly letter containing 200-300 Chinese characters. Chiang Kai-shek also underlined the importance of classical books and of learning English, two areas he was hardly proficient in himself.[2] On March 20, 1924, Ching-kuo was able to present to his now-nationally famous father a proposal concerning the grass-roots organization of the rural population in Hsikou.[3] Chiang Ching-kuo planned to provide free education in order to allow people to read and to write at least 1000 characters. In his own words:

I have a suggestion to make about the Wushan School, although I do not know if you can agree to it. My suggestion is that the school establish a night school for common people who cannot afford to go to the regular school. My school established a night school with great success. I can tell you something about the night school: Name: Wuschua School for the Common People Tuition fee: Free of charge with stationery supplied Class hours: 7 pm to 9 pm Age limit: 14 or older Schooling protocol: 16 or 20 weeks. At the time of the graduation, the trainees will be able to write simple letters and keep simple accounts. They will be issued a diploma if they pass the examinations. The textbooks they used were published by the Commercial Press and were entitled "One thousand characters for the common people." I do not know whether you will accept my suggestion. If a night school is established at Wushan, it will greatly benefit the local people.

His father's reply was negative; Kai-shek stating that rural peasants were not interested in, nor needed, a formal education.

In early 1925, Chiang Ching-kuo entered the Shanghai's Pudong college, but immediately afterwards Chiang Kai-shek decided to send him on to Beijing because of warlord action and spontaneous riots in Shanghai. In Beijing he attended the school organized by a friend of his father, Wu Chih-hui (吳稚暉), a renowned scholar and linguist. The school combined classical and modern approaches to education. While there, Ching-kuo started to identify himself as a progressive revolutionary and participated in the flourishing social scene inside the young Communist community. The idea of studying in Moscow now seized his imagination.[4] Within the help program provided by the Soviet Union to the countries of East Asia there was a training school that later became the Moscow Sun Yat-sen University. The participants to the university were selected by the CPSU and KMT members, with a participation of CPC Central Committee.[5]

Chiang Ching-kuo asked his teacher Wu Chih-hui to name him as a KMT candidate. Though Wu Chih-hui did not try to dissuade him, Wu was a key figure of the right-leaning and anti-Communist "Western Hills Group" of the Kuomintang, which help to realize the purge of the Communist and the KMT break with Moscow. In the summer of 1925, Chiang Ching-kuo traveled to Whampoa to discuss with his father about the plans to go to Moscow.

Chiang Kai-shek was not keen on sending his son to the USSR, but after a discussion with Ch'en Kuo-fu (陳果夫) he finally agreed. In a 1996 interview, Ch'en's brother, Li-fu, claimed that the reason behind Chiang Kai-shek acceptance was the need to have Soviet support during a period when his hold over the KMT was not guaranteed.[6]

Moscow

In 1925, Chiang Ching-Kuo went on to Moscow to study at a Communist school. While in Moscow, Ching-kuo was given the Russian name Nikolai Vladimirovich Elizarov (Николай Владимирович Елизаров) and put under the tutelage of Karl Radek at the Communist University of the Toilers of the East. Noted for having an exceptional grasp of international politics, his classmates included other children of influential Chinese families, most notably the future Chinese Communist party leader, Deng Xiaoping. Soon Ching-kuo was an enthusiastic student of Communist ideology, particularly Trotskyism; though following the Great Purge, Joseph Stalin privately met with him and ordered him to publicly denounce Trotskyism. Chiang even applied to be a member of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, although his request was denied.

In April 1927, however, Chiang Kai-Shek purged the KMT leftists and Communists from the Central Government and expelled his Soviet advisers. Following this, Chiang Ching-kuo wrote an editorial that harshly criticized his father's actions and was detained as a "guest" of the Soviet Union as a practical hostage. Debate still continues as to whether he had been forced to write it, and it is known that some years beforehand he had seen many of his Trotskyist friends arrested and killed by the Russian secret police. It is possible that Chiang Ching-kuo has been held to be used by Stalin as leverage in Sino-Soviet relationships. Nevertheless, the Soviet government sent Chiang Ching-kuo to work in the Ural Heavy Machinery Plant, a steel factory in the Urals, Yekaterinburg, where he met Faina Ipat'evna Vakhreva, a native Belarusian. They married on March 15, 1935, and she would later become known as Chiang Fang-liang. In December of that year, a son, Hsiao-wen was born. A daughter, Hsiao-chang, was born the next year.

Chiang Kai-shek wrote about the situation in his diary, "It is not worth it to sacrifice the interest of the country for the sake of my son."[7][8] Chiang even refused to negotiate a prisoner swap for his son in exchange for the Chinese Communist Party leader.[9] His attitude remained consistent, and he continued to maintain, by 1937, that "I would rather have no offspring than sacrifice our nation's interests." Chiang had absolutely no intention of stopping the war against the Communists.[10]

Stalin allowed Chiang Ching-kuo to return to China with his Belarusian wife and two children in April 1937 after living in the USSR for 12 years. By then, the Nationalists under Chiang Kai-shek and the Communists under Mao Zedong had signed a ceasefire to create the Second United Front and fight the Japanese invasion of China, which began in July. Stalin hoped the Chinese would keep Japan from invading the Soviet Pacific coast, and he hoped to form an anti-Japanese alliance with the senior Chiang.

On his return, his father assigned a tutor, Hsu Dau-lin, to assist with his readjustment to China.[11] Chiang Ching-Kuo was appointed as a specialist in remote districts of Jiangxi where he was credited with training of cadres and fighting corruption, opium consumption, and illiteracy. Chiang Ching-kuo was appointed as commissioner of Gannan Prefecture (Chinese: 贛南) between 1939 and 1945; there he banned smoking, gambling and prostitution, studied governmental management, allowed for economic expansion and a change in social outlook. His efforts were hailed as a miracle in the political war in China, then coined as the "Gannan New Deal" (贛南新政). During his time in Gannan, from 1940 he implemented a "public information desk" where ordinary people could visit him if they had problems, and according to records, Chiang Ching-kuo received a total of 1,023 people during such sessions in 1942. In regards to the ban on prostitution and closing of brothels, Chiang implemented a policy where former prostitutes became employed in factories. Due to the large number of refugees in Ganzhou as a result from the ongoing war, thousands of orphans lived on the street; in June 1942, Chiang Ching-kuo formally established the Chinese Children's Village (中華兒童新村) in the outskirts of Ganzhou, with facilities such as a nursery, kindergarten, primary school, hospital and gymnasium. During the last years of the 1930s, he met Wang Sheng, with whom he would remain close for the next 50 years.

The paramilitary "Sanman Zhuyi Youth Corps" was under Chiang's control. Chiang used the term "big bourgeoisie", in a disparaging manner to call H.H. Kung and T.V. Soong.[12]

Chiang and his wife had two more sons, Hsiao-wu, born in Chungking, and Hsiao-yung, born in Shanghai. Out of his affair with Chang Ya-juo, Chiang also had twin sons in 1941: Chang Hsiao-tz'u and Chang Hsiao-yen. (Note the identical generation name of Hsiao between all sons, legitimate or not.)

Hostage claim

Jung Chang and Jon Halliday claim that Chiang Kai-shek allowed the Communists to escape on the Long March, allegedly because he wanted his son Chiang Ching-kuo who was being held hostage by Joseph Stalin back.[13] This is contradicted by Chiang Kai-shek himself, who wrote in his diary, "It is not worth is to sacrifice the interest of the country for the sake of my son." [14][15] Chiang even refused to negotiate for a prisoner swap, of his son in exchange of the Chinese Communist Party leader.[16] Again in 1937 he stated about his son- "I would rather have no offspring than sacrifice our nation's interests." Chiang had absolutely no intention of stopping the war against the Communists.[17] Chiang Kaishek urged the Ma warlords of northwest China to hammer away at the communists, including allowing the governor of Qinghai to stay in office since he wiped out an entire communist army.[18]

Chang and Halliday also made another claim asserting Chiang Ching-kuo was "kidnapped", however evidence shows that he went to study in the Soviet Union with Chiang Kai-shek's own approval.[13]

Economic policies in Shanghai

After the Second Sino-Japanese War and during the Chinese Civil War, Chiang Ching-kuo briefly served as a liaison administrator in Shanghai, trying to eradicate the corruption and hyperinflation that plagued the city. He was determined to do this because of the fears arising from the Nationalists' increasing lack of popularity during the Civil War. Given the task of arresting dishonest businessmen who hoarded supplies for profit during the inflationary spiral, he attempted to assuage the business community by explaining that his team would only go after big war profiteers.

Ching-kuo copied Soviet methods, which he learned during his stay in the Soviet Union, to start a social revolution by attacking middle class merchants. He also enforced low prices on all goods to raise support from the Proletariat.[19]

As riots broke out and savings were ruined, bankrupting shopowners, Ching-kuo began to attack the wealthy, seizing assets and placing them under arrest. The son of the gangster Du Yuesheng was arrested by him. Ching-kuo ordered Kuomintang agents to raid the Yangtze Development Corporation's warehouses, which was privately owned by H.H. Kung and his family, as the company was accused of hoarding supplies. H.H. Kung's wife was Soong Ai-ling, the sister of Soong May-ling who was Ching-kuo's stepmother. H.H. Kung's son David was arrested, the Kung's responded by blackmailing the Chiang's, threatening to release information about them, eventually he was freed after negotiations, and Ching-kuo resigned, ending the terror on the Shanghainese merchants.[20]

Political career in Taiwan

After the Nationalists lost control of mainland China to the Communists in the Chinese Civil War, Chiang Ching-kuo followed his father and the retreating Nationalist forces to Taiwan. On December 8, 1949, the Nationalist capital was moved from Chengdu to Taipei, and early on December 10, 1949, Communist troops laid siege to Chengdu, the last KMT controlled city on mainland China. Here Chiang Kai-shek and his son Chiang Ching-kuo directed the city's defense from the Chengdu Central Military Academy, before the aircraft May-ling evacuated them to Taiwan; they would never return to mainland China.

In 1950, Chiang's father appointed him director of the secret police, which he remained until 1965. An enemy of the Chiang family, Wu Kuo-chen, was kicked out of his position of governor of Taiwan by Chiang Ching-kuo and fled to America in 1953.[21] Chiang Ching-kuo, educated in the Soviet Union, initiated Soviet style military organization in the Republic of China Military, reorganizing and Sovietizing the political officer corps, surveillance, and Kuomintang party activities were propagated throughout the military. Opposed to this was Sun Li-jen, who was educated at the American Virginia Military Institute.[22] Chiang orchestrated the controversial court-martial and arrest of General Sun Li-jen in August 1955, allegedly for plotting a coup d'état with the American CIA against his father.[23][24] General Sun was a popular Chinese war hero from the Burma Campaign against the Japanese and remained under house arrest until Chiang Ching-kuo's death in 1988. Ching-kuo also approved the arbitrary arrest and torture of prisoners.[25] Chiang Ching-kuo's activities as director of the secret police remained widely criticized as heralding a long era of human rights abuses in Taiwan.

From 1955 to 1960, Chiang administered the construction and completion of Taiwan's highway system. Chiang's father elevated him to high office when he was appointed as the ROC Defense Minister from 1965 until 1969. He was the nation's Vice Premier between 1969 and 1972, during which he survived an assassination attempt while visiting the U.S. in 1970. Afterwards he was appointed the nation's Premier between 1972 and 1978. As Chiang Kai-shek entered his final years, he gradually gave more responsibilities to his son, and when he died in April 1975, the presidency was turned over to Yen Chia-kan and Chiang Ching-kuo succeeded to the leadership of the Kuomintang (he opted for the title "Chairman" rather than the elder Chiang's title of "Director-General").

Presidency

Chiang was officially elected President of the Republic of China by the National Assembly after the term of President Yen Chia-kan on May 20, 1978. He was reelected to another term in 1984. At that time, the National Assembly consisted mostly of "thousand year" legislators, men who had been elected in 1947-48 before the fall of mainland China and who would hold their seats indefinitely.

During the early years of his term in office Chiang maintained many of his father's autocratic policies, continuing to rule Taiwan as a military state under martial law as it had been since the Nationalists established its capital there.

In a move that broke from his father's domineering industrial and economic policies, Ching-kuo launched the "Fourteen Major Construction Projects", the "Ten Major Construction Projects" and the "Twelve New Development Projects" which contributed to the "Taiwan Miracle." Among his accomplishments were accelerating the process of economic modernization to give Taiwan a 13% growth rate, $4,600 per capita income, and the world's second largest foreign exchange reserves.

However, in December 1978, U.S. President, Jimmy Carter announced that the United States would no longer recognize the ROC as the legitimate government of China. Under the Taiwan Relations Act, the United States would continue to sell weapons to Taiwan, but the TRA was purposely vague in any promise of defending Taiwan in the event of an invasion. The United States would now end all official contact with the Chiang's government and withdraw its troops from the island.

In an effort of bringing more Taiwan-born citizens into government services, Chiang Ching-kuo "exiled" his over-ambitious chief of General Political Warfare Department, General Wang Sheng, to Paraguay as an ambassador (November 1983),[26] and hand-picked Lee Teng-hui as vice-president of the Republic of China (formally elected May 1984), first-in-the-line of succession to the presidency.

In 1987, Chiang finally ended martial law and allowed family visits to the Mainland China. His administration saw a gradual loosening of political controls and opponents of the Nationalists were no longer forbidden to hold meetings or publish papers. Opposition political parties, though still illegal, were allowed to form without harassment or arrest. When the Democratic Progressive Party was established in 1986, President Chiang decided against dissolving the group or persecuting its leaders, but its candidates officially ran in elections as independents in the Tangwai movement.

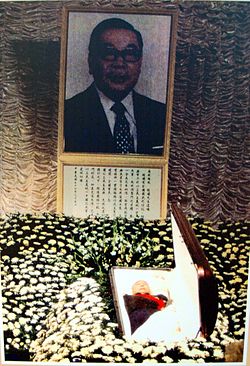

Death and legacy

Chiang died of heart failure and hemorrhage in Taipei at the age of 78. Like his father, he was interred temporarily in Daxi (Tahsi) Township, Taoyuan County, but in a separate mausoleum in Touliao, a mile down the road from his father's burial place. The hope was to have both buried at their birthplace in Fenghua once mainland China was recovered. Chinese music composer Hwang Yau-tai or Huang Youdi, Huang Yu-ti (黃友棣) wrote the Chiang Ching-kuo Memorial Song in 1988. In January 2004, Chiang Fang-liang asked that both father and son be buried at Wuchih Mountain Military Cemetery in Hsichih, Taipei County (now New Taipei City). The state funeral ceremony was initially planned for Spring 2005, but was eventually delayed to winter 2005. It may be further delayed due to the recent death of Chiang Ching-kuo's oldest daughter-in-law, who had served as the de-facto head of the household since Chiang Fang-liang's death in 2004. Chiang Fang-liang and Soong May-ling had agreed in 1997 that the former leaders be first buried, but still be moved to mainland China.

Unlike his father Chiang Kai-shek, Chiang Ching-kuo built himself a folk reputation that remains generally known even among local Taiwanese electorate. Both his memory and image are frequently invoked by the Kuomintang, which is unable to base their electoral campaign on Chiang's successor, President and KMT Chairman Lee Teng-hui because of Lee's support of Taiwan for Taiwanese. Chiang Ching-kuo, however, did admit he had become "Taiwanese" after fleeing mainland China in 1949.

Among the Tangwai and later the Pan-Green Coalition, opinions toward Chiang Ching-kuo are more reserved. While long-time supporters of political liberalization do give Chiang Ching-kuo credit for relaxing authoritarian rule, they point out that Taiwan remained authoritarian throughout the early years of his rule, and only liberalized in his twilight years. Nonetheless, as with Pan-Blue followers, he is recognized for his efforts and openness in economic developments.

Under President Chen Shui-bian, pictures of Chiang Ching-kuo and his father gradually disappeared from public buildings. The AIDC, the ROC's air defense company, has nicknamed its AIDC F-CK Indigenous Defense Fighter the Ching Kuo in his memory.

All of his legitimate children studied abroad and two of his children married in the United States. Only two remain living: John Chiang is a prominent KMT politician, while Chiang Hsiao-chang, her children and grandchildren reside in the United States.

See also

- Seven Seas Residence

- Chiang Kai-shek

- Madame Chiang Kai-shek

- History of the Republic of China

- Military of the Republic of China

- President of the Republic of China

- Politics of the Republic of China

- Second Sino-Japanese War

- National Revolutionary Army

- Kuomintang

- Sino-German cooperation

- Chiang Ching-kuo Foundation

Notes

- Many sources, even Taiwanese official ones, give March 18, 1910 as his birthday, but this actually refers to the traditional Chinese lunar calendar

References

- ^ [1]

- ^ letter of August 4, 1922

- ^ Wang Shun-ch'i, unpublished article, 1995. The letter is in the Nanking archive

- ^ Cline, Chiang Ching-kuo remembered, p. 148

- ^ Aleksander Pantsov, "From Students to dissidents. The Chinese Troskyites in Soviet Russia (Part 1)", in issues & Studies, 30/3 (March 1994), Institute of international relations, Taipei, pp. 113-114

- ^ Ch'en Li-fu, interview, Taipei, May 29, 1996

- ^ Jay Taylor (2000). The Generalissimo's son: Chiang Ching-kuo and the revolutions in China and Taiwan. Harvard University Press. p. 59. ISBN 0674002873. http://books.google.com/books?id=_5R2fnVZXiwC&pg=PA59&dq=It+is+not+worth+it+to+sacrifice+the+interest+of+the+country+for+the+sake+of+my+son&hl=en&ei=vwe9TIvGF8L78Aa81ZzGDw&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CCUQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=It%20is%20not%20worth%20it%20to%20sacrifice%20the%20interest%20of%20the%20country%20for%20the%20sake%20of%20my%20son&f=false. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Jonathan Fenby (2005). Chiang Kai Shek: China's Generalissimo and the Nation He Lost. Carroll & Graf Publishers. p. 205. ISBN 0786714840. http://books.google.com/books?id=YkREps9oGR4C&pg=PA205&dq=It+is+not+worth+it+to+sacrifice+the+interests+of+the+country+for+the+sake+of+my+son&hl=en&ei=MgW9TNvcKsP78Abztqi1Dw&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=2&ved=0CCoQ6AEwAQ#v=onepage&q=It%20is%20not%20worth%20it%20to%20sacrifice%20the%20interests%20of%20the%20country%20for%20the%20sake%20of%20my%20son&f=false. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Hannah Pakula (2009). The last empress: Madame Chiang Kai-shek and the birth of modern China. Simon and Schuster. p. 247. ISBN 1439148937. http://books.google.com/books?id=4ZpVntUTZfkC&pg=PA247&dq=It+is+not+worth+it+to+sacrifice+the+interest+of+the+country+for+the+sake+of+my+son&hl=en&ei=vAi9TLi0M8H68Ab-hJjsDg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=2&ved=0CC0Q6AEwAQ#v=onepage&q=It%20is%20not%20worth%20it%20to%20sacrifice%20the%20interest%20of%20the%20country%20for%20the%20sake%20of%20my%20son&f=false. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Jay Taylor (2000). The Generalissimo's son: Chiang Ching-kuo and the revolutions in China and Taiwan. Harvard University Press. p. 74. ISBN 0674002873. http://books.google.com/books?id=_5R2fnVZXiwC&pg=PA59&dq=chiang+sacrifice+son&hl=en&ei=nQW9TLK5MoT68Aaw9uAC&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CCUQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=chiang%20son%20i%20would%20rather%20have%20no%20offspring%20than%20sacrifice%20our%20%20interests&f=false. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Taylor, Jay. 2000. The Generalissimo’s son: Chiang Ching-kuo and the revolutions in China and Taiwan. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts

- ^ Laura Tyson Li (2007). Madame Chiang Kai-Shek: China's Eternal First Lady (reprint, illustrated ed.). Grove Press. p. 148. ISBN 0802143229. http://books.google.com/books?id=FRY0v7AH2ngC&pg=PA148&lpg=PA148&dq=h+h+kung+hitler&source=bl&ots=4_9e6yO6vT&sig=_2IqNEAzXn8_eXdVgadVZzUuLWI&hl=en&ei=OBbYTZO9GqLx0gGs2Mn8Aw&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=9&ved=0CEQQ6AEwCDge#v=onepage&q=big%20bourgeoisie&f=false. Retrieved 2011-05-21.

- ^ a b "A swan's little book of ire". The Sydney Morning Herald. 2005-10-08. http://www.smh.com.au/news/world/a-swans-little-book-of-ire/2005/10/07/1128563003642.html. Retrieved 2007-12-08.

- ^ Jay Taylor (2000). The Generalissimo's son: Chiang Ching-kuo and the revolutions in China and Taiwan. Harvard University Press. p. 59. ISBN 0674002873. http://books.google.com/books?id=_5R2fnVZXiwC&pg=PA59&dq=It+is+not+worth+it+to+sacrifice+the+interest+of+the+country+for+the+sake+of+my+son&hl=en&ei=vwe9TIvGF8L78Aa81ZzGDw&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CCUQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=It%20is%20not%20worth%20it%20to%20sacrifice%20the%20interest%20of%20the%20country%20for%20the%20sake%20of%20my%20son&f=false. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Jonathan Fenby (2005). Chiang Kai Shek: China's Generalissimo and the Nation He Lost. Carroll & Graf Publishers. p. 205. ISBN 0786714840. http://books.google.com/books?id=YkREps9oGR4C&pg=PA205&dq=It+is+not+worth+it+to+sacrifice+the+interests+of+the+country+for+the+sake+of+my+son&hl=en&ei=MgW9TNvcKsP78Abztqi1Dw&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=2&ved=0CCoQ6AEwAQ#v=onepage&q=It%20is%20not%20worth%20it%20to%20sacrifice%20the%20interests%20of%20the%20country%20for%20the%20sake%20of%20my%20son&f=false. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Hannah Pakula (2009). The last empress: Madame Chiang Kai-Shek and the birth of modern China. Simon and Schuster. p. 247. ISBN 1439148937. http://books.google.com/books?id=4ZpVntUTZfkC&pg=PA247&dq=It+is+not+worth+it+to+sacrifice+the+interest+of+the+country+for+the+sake+of+my+son&hl=en&ei=vAi9TLi0M8H68Ab-hJjsDg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=2&ved=0CC0Q6AEwAQ#v=onepage&q=It%20is%20not%20worth%20it%20to%20sacrifice%20the%20interest%20of%20the%20country%20for%20the%20sake%20of%20my%20son&f=false. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Jay Taylor (2000). The Generalissimo's son: Chiang Ching-kuo and the revolutions in China and Taiwan. Harvard University Press. p. 74. ISBN 0674002873. http://books.google.com/books?id=_5R2fnVZXiwC&pg=PA59&dq=chiang+sacrifice+son&hl=en&ei=nQW9TLK5MoT68Aaw9uAC&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CCUQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=chiang%20son%20i%20would%20rather%20have%20no%20offspring%20than%20sacrifice%20our%20%20interests&f=false. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Uradyn Erden Bulag (2002). Dilemmas The Mongols at China's edge: history and the politics of national unity. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 50. ISBN 0742511448. http://books.google.com/books?id=g3C2B9oXVbQC&printsec=frontcover&dq=mongols+at+china's+edge&hl=en&src=bmrr&ei=SXO4Td7ILI-C0QGLkfD8Dw&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CDEQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=ma%20bufang%20resign&f=false. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Jonathan Fenby (2005). Chiang Kai Shek: China's Generalissimo and the Nation He Lost. Carroll & Graf Publishers. p. 485. ISBN 0786714840. http://books.google.com/books?id=YkREps9oGR4C&dq=soong+slap+chiang&q=chiang+middle+class+social+revolution+soviet#v=snippet&q=middle%20class%20social%20revolution%20soviet&f=false. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Jonathan Fenby (2005). Chiang Kai Shek: China's Generalissimo and the Nation He Lost. Carroll & Graf Publishers. p. 486. ISBN 0786714840. http://books.google.com/books?id=YkREps9oGR4C&pg=PA339&dq=soong+slap+chiang&hl=en&ei=r4SmTLqoMoSKlwemtZQY&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=2&ved=0CDAQ6AEwAQ#v=onepage&q=ching-kuo%20turned%20on%20rich%20assets%20agents%20raided&f=false. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Peter R. Moody (1977). Opposition and dissent in contemporary China. Hoover Press. p. 302. ISBN 0817967710. http://books.google.com/books?id=AW9yrtekFRkC&pg=PA302&dq=sun+li+jen+americans+chiang&hl=en&ei=I679TJ2CMcKqlAfOu6WACQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=7&ved=0CEAQ6AEwBg#v=onepage&q=sun%20li%20jen%20americans%20chiang&f=false. Retrieved 2010-11-30.

- ^ Jay Taylor (2000). The Generalissimo's son: Chiang Ching-kuo and the revolutions in China and Taiwan. Harvard University Press. p. 195. ISBN 0674002873. http://books.google.com/books?id=_5R2fnVZXiwC&pg=PA195&dq=sun+li+jen+americans+chiang&hl=en&ei=I679TJ2CMcKqlAfOu6WACQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=2&ved=0CCcQ6AEwAQ#v=onepage&q=sun%20li%20jen%20americans%20chiang&f=false. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Peter R. Moody (1977). Opposition and dissent in contemporary China. Hoover Press. p. 302. ISBN 0817967710. http://books.google.com/books?id=AW9yrtekFRkC&pg=PA302&dq=sun+li+jen+americans+chiang&hl=en&ei=I679TJ2CMcKqlAfOu6WACQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=7&ved=0CEAQ6AEwBg#v=onepage&q=sun%20li%20jen%20americans%20chiang&f=false. Retrieved 2010-11-30.

- ^ Nançy Bernkopf Tucker (1983). Patterns in the dust: Chinese-American relations and the recognition controversy, 1949-1950. Columbia University Press. p. 181. ISBN 0231053622. http://books.google.com/books?id=YoB35f6HD9gC&pg=PA181&dq=sun+li+jen+americans+chiang&hl=en&ei=I679TJ2CMcKqlAfOu6WACQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=10&ved=0CFEQ6AEwCQ#v=onepage&q=sun%20li%20jen%20americans%20chiang&f=false. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ John W. Garver (1997). The Sino-American alliance: Nationalist China and American Cold War strategy in Asia. M.E. Sharpe. p. 243. ISBN 0765600250. http://books.google.com/books?id=ZNCghCIbyVAC&pg=PA243&dq=sun+li+jen+americans+chiang&hl=en&ei=PrP9TMTUMoWKlwfV59z0CA&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=4&ved=0CDEQ6AEwAw#v=onepage&q&f=false. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Roy, Denny (2003). Taiwan: a political history. Cornell University Press. pp. 179–180. ISBN 0801488052. http://books.google.com/books?id=DNqasVI-gWMC.

- Taylor, Jay. The Generalissimo's Son: Chiang Ching-Kuo and the Revolutions in China and Taiwan. ISBN 0-674-00287-3

External links

- ROC Government biography

- Remembering Chiang Ching-kuo

- 1981 GIO video: Hello, Mr. President-Chiang Ching-kuo and His People

- Kuomintang Official Website

Government offices Preceded by

Yu DaweiMinister of National Defence of the Republic of China

1965 – 1969Succeeded by

Huang ChiehPreceded by

Yen Chia-kanPremier of the Republic of China

1972 – 1978Succeeded by

Sun Yun-suanPolitical offices Preceded by

Yen Chia-kanPresident of the Republic of China

1978 – 1988Succeeded by

Lee Teng-huiParty political offices Preceded by

Chiang Kai-shek

Director-General of the KuomintangChairman of the Kuomintang

1975–1988Succeeded by

Lee Teng-huiPresidents of the Republic of China Provisional Government

(1912–1913)

Beiyang Government

(1913–1928)Yuan Shikai · Li Yuanhong · Feng Guozhang · Xu Shichang · Zhou Ziqi · Li Yuanhong · Gao Lingwei · Cao Kun · Huang Fu · Hu Weide · Yan Huiqing · Du Xigui · Gu WeijunNationalist Government

(1928–1948)Constitutional Government

(since 1948)Chiang Kai-shek · Li Zongren · Chiang Kai-shek · Yen Chia-kan · Chiang Ching-kuo · Lee Teng-hui · Chen Shui-bian · Ma Ying-jeouItalics indicates acting President Heads of government of the Republic of China Premiers of Cabinet

Secretaries of State Premiers of State Council Prime Minister of Restored

Qing Imperial GovernmentPremiers of State Council Duan Qirui · Wang Daxie* · Wang Shizhen* · Qian Nengxun* · Gong Xinzhan* · Jin Yunpeng · Sa Zhenbing · Yan Huiqing* · Liang Shiyi · Zhou Ziqi* · Wang Chonghui* · Wang Zhengting* · Zhang Shaozeng · Gao Lingwei · Sun Baoqi · V.K. Wellington Koo (Vi-kyuin)* · Huang Fu* · Xu Shiying · Jia Deyao* · Hu Weide* · Du Xigui* · Pan FuPresidents of Executive Yuan Tan Yankai · T. V. Soong (Tse-ven) · Chiang Kai-shek · Chen Mingshu · Sun Fo · Wang Jingwei · H. H. Kung (Hsiang-hsi) · Chang Ch'ün · Weng Wenhao · Sun Fo · He Yingqin · Yan Xishan · Chen Cheng · Yu Hung-Chun · Yen Chia-kan · Chiang Ching-kuo · Sun Yun-suan · Yu Kuo-hwa · Lee Huan · Hau Pei-tsun · Lien Chan · Vincent Siew Wan-chang · Tang Fei · Chang Chun-hsiung · Yu Shyi-kun · Frank Hsieh Chang-ting · Su Tseng-chang · Liu Chao-shiuan · Wu Den-yih* actingLeaders of the Kuomintang Song Jiaoren • Sun Yat-sen • Zhang Renji • Hu Hanmin • Wang Jingwei • Chiang Kai-shek • Chiang Ching-kuo • Lee Teng-hui • Lien Chan • Ma Ying-jeou • Chiang Pin-kung (acting) • Wu Po-hsiung • Ma Ying-jeou

Chinese Civil War Main events pre-1945 Main events post-1945 Specific articles - Sino-Soviet conflict (1929)

- Encirclement Campaigns (1930–1934)

- Chinese Soviet Republic (1931–1934)

- Long March (1934–1936)

- Xi'an Incident (1936)

- Second United Front (1937–1946)

Part of the Cold War

- Full-scale Civil War (1946–1949)

- Kuomintang Islamic Insurgency in China (1950–1958)

- Campaign at the China–Burma Border (1960-1961)

- First Taiwan Strait Crisis (1955)

- Second Taiwan Strait Crisis (1958)

- Third Taiwan Strait Crisis (1996)

- Pan-Blue visits to mainland China (2005-)

- Political status of Taiwan

- Legal status of Taiwan

- Chinese reunification

- Taiwan independence

- Cross-Strait relations

Primary participants

Notable figures of the Cold WarSoviet Union Joseph Stalin · Vyacheslav Molotov · Andrei Gromyko · Nikita Khrushchev · Anatoly Dobrynin · Leonid Brezhnev · Alexei Kosygin · Yuri Andropov · Konstantin Chernenko · Mikhail Gorbachev · Nikolai Ryzhkov · Eduard Shevardnadze · Gennady Yanayev · Boris YeltsinUnited States People's Republic of China Japan West Germany United Kingdom Italy France Finland Spain People's Republic of Poland Canada Philippines Africa José Eduardo dos Santos · Jonas Savimbi (Angola) · Patrice Lumumba · Mobutu Sese Seko (Congo/Zaire) · Agostinho Neto · Mengistu Haile Mariam (Ethiopia) · Kwame Nkrumah (Ghana) · Julius Nyerere (Tanzania) · Idi Amin (Uganda) · Muammar Gaddafi (Libya)Eastern Bloc Enver Hoxha (Albania) · Todor Zhivkov (Bulgaria) · Alexander Dubček (Czechoslovakia) · Walter Ulbricht · Erich Honecker (East Germany) · Mátyás Rákosi · Imre Nagy · János Kádár (Hungary) · Nicolae Ceauşescu (Romania) · Josip Broz Tito (Yugoslavia)Latin America Juan Domingo Perón · Jorge Rafael Videla · Leopoldo Galtieri (Argentina) · Getúlio Vargas · Luís Prestes · Leonel Brizola · João Goulart · Castelo Branco (Brazil) · Salvador Allende · Augusto Pinochet (Chile) · Fidel Castro · Che Guevara (Cuba) · Daniel Ortega (Nicaragua) · Rómulo Betancourt (Venezuela)Middle East Mohammad Najibullah · Ahmad Shah Massoud (Afghanistan) · Gamal Abdel Nasser · Anwar Sadat (Egypt) · Mohammad Reza Pahlavi · Mohammad Mosaddegh · Ayatollah Khomeini (Iran) · Saddam Hussein (Iraq) · Menachem Begin (Israel)South and East Asia Sheikh Mujibur Rahman (Bangladesh) · U Nu · Ne Win (Burma) · Pol Pot (Cambodia) · Indira Gandhi · Jawaharlal Nehru (India) · Sukarno · Suharto · Mohammad Hatta · Adam Malik (Indonesia) · Kim Il-sung (North Korea) · Syngman Rhee · Park Chung-hee (South Korea) · Muhammad Ayub Khan · Zulfikar Ali Bhutto · Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq (Pakistan) · Chiang Kai-shek · Chiang Ching-kuo (Taiwan) · Ho Chi Minh (North Vietnam) · Ngo Dinh Diem (South Vietnam)Category · Portal · Timeline of events Categories:- Presidents of the Republic of China on Taiwan

- Chinese anti-communists

- Chinese people of World War II

- Chiang Kai-shek family

- Cardiovascular disease deaths in Taiwan

- 1910 births

- 1988 deaths

- Cold War leaders

- Attempted assassination survivors

- People from Ningbo (birthplace)

- Premiers of the Republic of China on Taiwan

- Taiwanese Christians

- Taiwanese Methodists

- Chinese Nationalist heads of state

- Chairpersons of the Kuomintang

- Republic of China politicians from Zhejiang

- Taiwanese Ministers of Defense

- Chinese expatriates in the Soviet Union

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.