- Catechol-O-methyl transferase

-

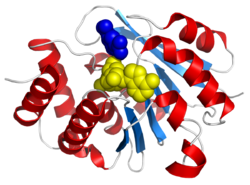

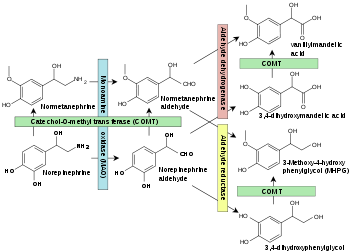

catechol-O-methyltransferase Identifiers EC number 2.1.1.6 CAS number 9012-25-3 Databases IntEnz IntEnz view BRENDA BRENDA entry ExPASy NiceZyme view KEGG KEGG entry MetaCyc metabolic pathway PRIAM profile PDB structures RCSB PDB PDBe PDBsum Gene Ontology AmiGO / EGO Search PMC articles PubMed articles  Norepinephrine degradation. Catechol-O-methyltransferase is shown in green boxes.[1]

Norepinephrine degradation. Catechol-O-methyltransferase is shown in green boxes.[1]

Catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT; EC 2.1.1.6) is one of several enzymes that degrade catecholamines such as dopamine, epinephrine, and norepinephrine. In humans, catechol-O-methyltransferase protein is encoded by the COMT gene.[2] As the regulation of catecholamines is impaired in a number of medical conditions, several pharmaceutical drugs target COMT to alter its activity and therefore the availability of catecholamines.[3] COMT was first discovered by the biochemist Julius Axelrod in 1957.[4]

Contents

Function

Catechol-O-methyltransferase is involved in the inactivation of the catecholamine neurotransmitters (dopamine, epinephrine, and norepinephrine). The enzyme introduces a methyl group to the catecholamine, which is donated by S-adenosyl methionine (SAM). Any compound having a catechol structure, like catecholestrogens and catechol-containing flavonoids, are substrates of COMT.

Levodopa, a precursor of catecholamines, is an important substrate of COMT. COMT inhibitors, like entacapone, save levodopa from COMT and prolong the action of levodopa. Entacapone is a widely-used adjunct drug of levodopa therapy. When given with an inhibitor of dopa decarboxylase (carbidopa or benserazide), levodopa is optimally saved. This "triple therapy" is becoming a standard in the treatment of Parkinson's disease.

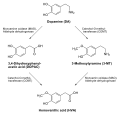

Specific reactions catalyzed by COMT include:

- Dopamine → 3-Methoxytyramine

- DOPAC → HVA (homovanillic acid)

- Norepinephrine → Normetanephrine

- Epinephrine → Metanephrine

- Dihydroxyphenylethylene glycol (DOPEG) → Methoxyhydroxyphenylglycol (MOPEG)

- 3,4-Dihydroxymandelic acid (DOMA) → Vanillylmandelic acid (VMA)

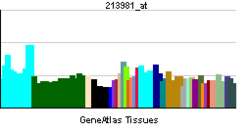

In the brain, COMT-dependent dopamine degradation is of particular importance in brain regions with low expression of the presynaptic dopamine transporter (DAT), such as the prefrontal cortex.[5][6] This process is supposed to take place in postsynaptic neurons as COMT is generally located intracellularly in the CNS [7][8].

COMT can also be found extracellularly, although extracellular COMT plays a less significant role in the CNS than it does peripherally.[9] Despite its importance in neurons, COMT is actually primarily expressed in the liver.[10]

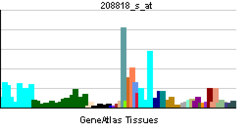

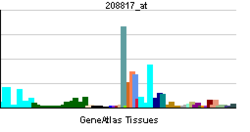

Genetics

The COMT protein is coded by the gene COMT. The gene is associated with allelic variants. The best-studied is Val158Met. Others are rs737865 and rs165599 that have been studied, e.g., for association with personality traits.[11]

The Val158Met polymorphism

A functional single-nucleotide polymorphism (a common normal variant) of the gene for catechol-O-methyltransferase results in a valine to methionine mutation at position 158 (Val158Met) rs4680 [12] The Val variant catabolizes dopamine at up to four times the rate of its methionine counterpart, resulting in significant lower synaptic dopamine levels following neurotransmitter release, ultimately reducing dopaminergic stimulation of the post-synaptic neuron. Given the preferential role of COMT in prefrontal dopamine degradation, the Val158Met polymorphism is thought to exert its effects on cognition by modulating dopamine signaling in the frontal lobes.

The gene variant has been shown to affect cognitive tasks broadly related to executive function, such as set shifting, response inhibition, abstract thought, and the acquisition of rules or task structure.[13][citation needed]

Comparable effects on similar cognitive tasks, the frontal lobes, and the neurotransmitter dopamine have also all been linked to schizophrenia. It has been proposed that an inherited variant of COMT is one of the genetic factors that may predispose someone to developing schizophrenia later in life, naturally or due to adolescent-onset cannabis use.[14] However, a more recent study cast doubt on the proposed connection between this gene and the effects of cannabis on schizophrenia development.[15]

It is increasingly recognised that allelic variation at the COMT gene are also relevant for emotional processing, as they seem to influence the interaction between prefrontal and limbic regions. Research conducted at the Section of Neurobiology of Psychosis, Institute of Psychiatry, King's College London has demonstrated an effect of COMT both in patients with bipolar disorder and in their relatives (Lelli-Chiesa et al., 2010)

The COMT Val158Met polymorphism also has a pleiotropic effect on emotional processing.[16][17] Furthermore, the polymorphism has been shown to affect ratings of subjective well-being. When 621 women were measured with experience sample monitoring, which is similar to mood assessment as response to beeping watch, the met/met form confers double the subjective mental sensation of well-being from a wide variety of daily events. The ability to experience reward increased with the number of ‘Met’ alleles.[18] Also, the effect of different genotype was greater for events that were felt as more pleasant. The effect size of genotypic moderation was quite large: Subjects with the val/val genotype generated almost similar amounts of subjective well-being from a ‘very pleasant event’ as met/met subjects did from a ‘bit pleasant event’. Genetic variation with functional impact on cortical dopamine tone has a strong influence on reward experience in the flow of daily life.[18] Persons with the met/met phenotype describe events as very pleasant or pleasant with twice the numeric amplitude of those absent the met/met genetic polymorphism.[18]

Nomenclature

COMT is the name given to the gene that codes for this enzyme. The O in the name stands for oxygen, not for ortho.

COMT inhibitors

COMT inhibitors include tolcapone and entacapone, which are commonly used in the treatment of Parkinson disease.[19]

See also

Additional images

References

- ^ Figure 11-4 in: Rod Flower; Humphrey P. Rang; Maureen M. Dale; Ritter, James M. (2007). Rang & Dale's pharmacology. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. ISBN 0-443-06911-5.

- ^ Grossman MH, Emanuel BS, Budarf ML (April 1992). "Chromosomal mapping of the human catechol-O-methyltransferase gene to 22q11.1-q11.2". Genomics 12 (4): s = 822–5. doi:10.1016/0888-7543(92)90316-K. PMID 1572656.

- ^ Tai CH, Wu RM (February 2002). "Catechol-O-methyltransferase and Parkinson's disease". Acta Med. Okayama 56 (1): 1–6. PMID 11873938.

- ^ Axelrod J (August 1957). "O-Methylation of Epinephrine and Other Catechols in vitro and in vivo". Science 126 (3270): 400–1. doi:10.1126/science.126.3270.400. PMID 13467217.

- ^ Matsumoto et al., 2003 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0306-4522(02)00556-0

- ^ Karoum et al., 1994 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.63030972.x/abstract

- ^ Ulmanen et al., 1997 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.0452a.x/abstract

- ^ Schott et al., 2010 http://www.frontiersin.org/molecular_psychiatry/10.3389/fpsyt.2010.00142/abstract

- ^ Golan, David E.; Armen H. Tashjian Jr.. Principles of pharmacology (3rd ed. ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health. pp. 210. ISBN 1-60831-270-4.

- ^ Golan, David E.; Armen H. Tashjian Jr.. Principles of pharmacology (3rd ed. ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health. pp. 135. ISBN 1-60831-270-4.

- ^ Stein MB, Fallin MD, Schork NJ, Gelernter J (November 2005). "COMT polymorphisms and anxiety-related personality traits". Neuropsychopharmacology 30 (11): 2092–102. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1300787. PMID 15956988.

- ^ Lotta T, Vidgren J, Tilgmann C, Ulmanen I, Melén K, Julkunen I, Taskinen J. (04-04-1995). "Kinetics of human soluble and membrane-bound catechol O-methyltransferase: a revised mechanism and description of the thermolabile variant of the enzyme.". Orion Research, Orion-Farmos, Orion Corporation, Espoo, Finland. PMID pmid7703232. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7703232.

- ^ Bruder GE, Keilp JG, Xu H, Shikhman M, Schori E, Gorman JM, Gilliam TC (December 2005). "Catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) genotypes and working memory: associations with differing cognitive operations". Biol. Psychiatry 58 (11): 901–7. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.05.010. PMID 16043133.

- ^ Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Cannon M, McClay J, Murray R, Harrington H, Taylor A, Arseneault L, Williams B, Braithwaite A, Poulton R, Craig IW (May 2005). "Moderation of the effect of adolescent-onset cannabis use on adult psychosis by a functional polymorphism in the catechol-O-methyltransferase gene: longitudinal evidence of a gene X environment interaction". Biol. Psychiatry 57 (10): 1117–27. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.01.026. PMID 15866551.

- ^ Zammit S, Spurlock G, Williams H, Norton N, Williams N, O'Donovan MC, Owen MJ (November 2007). "Genotype effects of CHRNA7, CNR1 and COMT in schizophrenia: interactions with tobacco and cannabis use". Br J Psychiatry 191: 402–7. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.107.036129. PMID 17978319. Lay summary – MedWireNews.

- ^ Lelli-Chiesa G, Kempton MJ, Jogia J, Tatarelli R, Girardi P, Powell J, Collier DA, Frangou S (July 2010). "The impact of the Val158Met catechol- O-methyltransferase genotype on neural correlates of sad facial affect processing in patients with bipolar disorder and their relatives". Psychol Med: 1–10. doi:10.1017/S0033291710001431. PMID 20667170.

- ^ Kempton MJ, Haldane M, Jogia J, Christodoulou T, Powell J, Collier D, Williams SC, Frangou S (April 2009). "The effects of gender and COMT Val158Met polymorphism on fearful facial affect recognition: a fMRI study". Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 12 (3): 371–81. doi:10.1017/S1461145708009395. PMID 18796186.

- ^ a b c Wichers M, Aguilera M, Kenis G, Krabbendam L, Myin-Germeys I, Jacobs N, Peeters F, Derom C, Vlietinck R, Mengelers R, Delespaul P, van Os J (December 2008). "The catechol-O-methyl transferase Val158Met polymorphism and experience of reward in the flow of daily life". Neuropsychopharmacology 33 (13): 3030–6. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1301520. PMID 17687265.

- ^ Bonifácio MJ, Palma PN, Almeida L, Soares-da-Silva P (2007). "Catechol-O-methyltransferase and its inhibitors in Parkinson's disease". CNS Drug Rev 13 (3): 352–79. doi:10.1111/j.1527-3458.2007.00020.x. PMID 17894650.

Further reading

- M. Wichers; Aguilera, M; Kenis, G; Krabbendam, L; Myin-Germeys, I; Jacobs, N; Peeters, F; Derom, C et al. (2008). "The Catechol-O-Methyl Transferase Val158Met Polymorphism and Experience of Reward in the Flow of Daily Life". Neuropsychopharmacology 33 ((2008) 33, 3030–3036): 3030–6. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1301520. PMID 17687265.http://www.nature.com/npp/journal/v33/n13/full/1301520a.html

- Trendelenburg U (1991). "The interaction of transport mechanisms and intracellular enzymes in metabolizing systems". J. Neural Transm. Suppl. 32: 3–18. PMID 2089098.

- Tai CH, Wu RM (2002). "Catechol-O-methyltransferase and Parkinson's disease". Acta Med. Okayama 56 (1): 1–6. PMID 11873938.

- Zhu BT (2003). "On the mechanism of homocysteine pathophysiology and pathogenesis: a unifying hypothesis". Histol. Histopathol. 17 (4): 1283–91. PMID 12371153.

- Oroszi G, Goldman D (2005). "Alcoholism: genes and mechanisms". Pharmacogenomics 5 (8): 1037–48. doi:10.1517/14622416.5.8.1037. PMID 15584875.

- Fan JB, Zhang CS, Gu NF, et al. (2005). "Catechol-O-methyltransferase gene Val/Met functional polymorphism and risk of schizophrenia: a large-scale association study plus meta-analysis". Biol. Psychiatry 57 (2): 139–44. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.10.018. PMID 15652872.

- Tunbridge EM, Harrison PJ, Weinberger DR (2006). "Catechol-o-methyltransferase, cognition, and psychosis: Val158Met and beyond". Biol. Psychiatry 60 (2): 141–51. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.10.024. PMID 16476412.

- Diaz-Asper CM, Weinberger DR, Goldberg TE (2006). "Catechol-O-methyltransferase polymorphisms and some implications for cognitive therapeutics". NeuroRx : the journal of the American Society for Experimental NeuroTherapeutics 3 (1): 97–105. doi:10.1016/j.nurx.2005.12.010. PMID 16490416.

- Craddock N, Owen MJ, O'Donovan MC (2006). "The catechol-O-methyl transferase (COMT) gene as a candidate for psychiatric phenotypes: evidence and lessons". Mol. Psychiatry 11 (5): 446–58. doi:10.1038/sj.mp.4001808. PMID 16505837.

- Frank MJ, Moustafa AA, Haughey H, Curran T, Hutchison KE (2007). "Genetic triple dissociation reveals multiple roles for dopamine in reinforcement learning". Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104 (41): 16311–6. doi:10.1073/pnas.0706111104. PMC 2042203. PMID 17913879. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2042203.

External links

Transferase: one carbon transferases (EC 2.1) 2.1.1: Methyl- N-O-5-hydroxyindole-O-methyltransferase/Acetylserotonin O-methyltransferase - Catechol-O-methyl transferaseOther2.1.2: Hydroxymethyl-,

Formyl- and RelatedHydroxymethyltransferaseFormyltransferaseOther2.1.3: Carboxy- and Carbamoyl CarboxyCarbamoyl2.1.4: Amidino Arginine:glycine amidinotransferasemonoamine anabolism: Tyrosine hydroxylase · Aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase · Dopamine beta hydroxylase · Phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase

catabolism: Catechol-O-methyl transferase · Monoamine oxidaseglutamate→GABAanabolism: Glutamate decarboxylase

catabolism: 4-aminobutyrate aminotransferase · 4-aminobutyrate transaminasearginine→NO choline→Acetylcholine anabolism: Choline acetyltransferase

catabolism: Cholinesterase (Acetylcholinesterase, Butyrylcholinesterase)Categories:- Human proteins

- EC 2.1.1

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.