- Japanese dialects

-

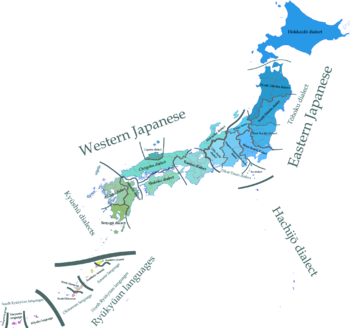

Japanese Geographic

distribution:Japan Linguistic classification: Japonic - Japanese

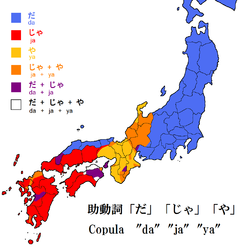

Subdivisions: HachijōEastern JapaneseWestern JapaneseKyūshūSatsugū Map of copula "da" "ja" "ya".

Map of copula "da" "ja" "ya".

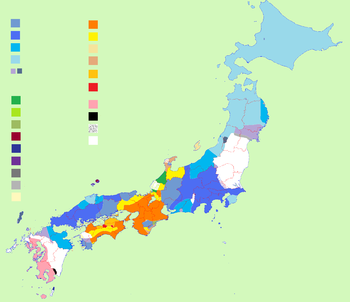

Map of Japanese pitch accent types.

Map of Japanese pitch accent types.

The Japanese dialects (方言 hōgen) comprise many regional variants. The lingua franca of Japan is called hyōjungo (標準語, lit. "standard language") or kyōtsūgo (共通語, lit. "common language"), and while it was based initially on the Tokyo dialect, the language of Japan's capital has since gone in its own direction to become one of Japan's many dialects. Dialects are commonly called -ben (弁, 辯, ex. "Osaka-ben", lit. "Osaka speech"), sometimes also called -kotoba (言葉, ことば, ex. "Edo-kotoba", lit. "Edo language") and -namari (訛り, なまり, ex. "Tōhoku-namari", lit. "Tōhoku accent").[1]

Contents

History

Regional variants of Japanese have been confirmed since the Old Japanese era. Man'yōshū, the oldest existing collection of Japanese poetry includes poems written in eastern dialects (See also Old Japanese#Dialects). From the Nara period to the Edo period, the dialect of Kinai (now central Kansai) had been the de facto standard Japanese, and the one of Edo (now Tokyo) took over in the late Edo period.

With modernization in the late 19th century, the government and the intellectuals promoted establishment and spread of the standard language. The regional languages and dialects were slighted and suppressed, and so locals had an inferiority complex about their "bad" and "shameful" languages. The language of instruction was standard Japanese, and some teachers administered punishments for using non-standard languages particularly in Okinawa and Tohoku regions (See also Ryukyuan languages#Modern history). In the years of 1940s to 1960s, the period of Shōwa nationalism and post-war economic miracle, the push for the standardization of regional languages/dialects reached its peak.

Now the standard Japanese spread throughout the nation and traditional regional languages/dialects are declining because of education, popularization of television, expansion of traffic and depopulation of countries. However, regional languages/dialects are not completely replaced with the standard Japanese. The spread of standard Japanese brings the regional languages/dialects to the scarcity value and many locals gradually conquer the inferiority complex about their languages/dialects. The contact between regional languages/dialects and standard Japanese invents new regional speech by young people.[2]

History of Japanese dialects[3] Before modern times Meiji to Showa Today (Future) Use of dialects active decline more decline Standardization start progress more progress Social value of dialects low extremely low high Activity over dialects extermination protection, promotion preservation as cultural property Character of dialects system style Function of dialects transmission of thinking confirmation of partner, expression of utterance attitude Classification

The classification of Japanese dialects has various theories. Misao Tōjō classified mainland Japanese dialects into three groups: Eastern, Western and Kyushu dialects as you can see below paragraphs. Toshio Tsuzuku included dialects in Gifu and Aichi prefectures to Western Japanese. Mitsuo Okumura classified Kyushu dialects as a subclass of Western Japanese. These theories are mainly based on grammatical differences between east and west, but Haruhiko Kindaichi classified mainland Japanese into concentric circlar three groups: inside (orange areas in the right map), middle (deep blue, Hokuriku, Kumano and southern Ehime areas) and outside (light blue, white, Hachijō, part of Noto, Izumo and Kyushu areas) based on systems of accent, phoneme and conjugation.

Eastern Japanese

Hokkaidō dialect

The residents of Hokkaidō are (relatively) recent arrivals from all parts of Japan, and this combination of influences has resulted in a set of regionalisms sometimes called Hokkaidō dialect (北海道弁 Hokkaidō-ben). The Hokkaidō dialect appears to have been influenced most significantly by the Tōhoku dialect, not surprising due to Hokkaidō's geographic proximity to northeastern Honshū. Overall, the Hokkaidō dialect is not dramatically different from what is called standard Japanese. However, the Hokkaidō dialect is different enough that it can be hard to understand on first hearing.

Ainu language is the language which used to be spoken by the native people of the Hokkaidō region before Japanese settled there from Heian era to Meiji era. The influence of Ainu language to Hokkaido dialect is very little.

Tōhoku dialect

The Tōhoku dialect is spoken in Tōhoku Region, the northeastern region of Honshū. Toward the northern part of Honshū, the Tōhoku dialect can differ so dramatically from standard Japanese that it is sometimes rendered with subtitles.

A notable linguistic feature of the Tōhoku dialect is its neutralization of the high vowels "i" and "u", so that the words sushi, susu (soot), and shishi (lion) are rendered homophonous, where they would have been distinct in other dialects. So Tōhoku dialect is sometimes referred to as "Zūzū-ben".

In addition, all unvoiced stops become voiced intervocalically, rendering the pronunciation of the word "kato" (trained rabbit) as [kado]. However, unlike the high vowel neutralization, this does not result in new homophones, as all voiced stops are pre-nasalized, meaning that the word "kado" (corner) is roughly pronounced [kando]. This is particularly noticeable with the "g" sound, which is nasalized sufficiently that it sounds very much like the English "ng" as in "thing", with the stop of the hard "g" almost entirely lost, so that ichigo 'strawberry' is pronounced [ɨzɨŋo].

The types of Tōhoku dialect can be broken down geographically:

- Northern Tohoku

- Tsugaru dialect (western Aomori Prefecture, around the former Tsugaru Domain)

- Nambu dialect (eastern Aomori Prefecture and northern Iwate Prefecture, around the former Nanbu Domain)

- Iwate dialect (northern Iwate Prefecture)

- Morioka dialect (around Morioka city)

- Shimokita dialect (Shimokita Peninsula, northeastern Aomori Prefecture)

- Akita dialect (Akita Prefecture)

- Shōnai dialect (northwestern Yamagata Prefecture, around the former Shonai Domain)

- Southern Tohoku

- Sendai dialect (Miyagi Prefecture especially Sendai)

- Iwate dialect (southern Iwate Prefecture)

- Kesen dialect (Kesen district, southeastern Iwate Prefecture)

- Yamagata dialect or Murayama dialect (central Yamagata Prefecture, around Yamagata city)

- Yonezawa dialect or Okitama dialect (southern Yamagata Prefecture, around Yonezawa city)

- Shinjō dialect or Mogami dialect (northeastern Yamagata Prefecture, around Shinjō city)

- Fukushima dialect (central Fukushima Prefecture)

- Aizu dialect (Aizu region in Fukushima Prefecture)

Kantō dialect

The Kantō dialect has some common features to the Tōhoku dialect, such as "-be" and "-nbe" being used to end sentences especially Eastern Kantō dialect. Tokyo and the suburbs' traditional dialects are steadily declining because standard Japanese started spreading in Kantō earlier than in other areas.

Types of Kanto dialect include:

- Western Kantō

- Tokyo dialect (Tokyo)

- Yamanote dialect (old upper-class dialect)

- Shitamachi dialect or Edo dialect (old working-class dialect)

- Tama dialect (Western Tokyo)

- Saitama dialect (Saitama Prefecture)

- Chichibu dialect (around Chichibu)

- Gunma dialect or Jōshū dialect (Gunma Prefecture)

- Kanagawa dialect (Kanagawa Prefecture)

- Bōshū dialect (southern Chiba Prefecture)

- Tokyo dialect (Tokyo)

- Eastern Kantō

- Ibaraki dialect (Ibaraki Prefecture)

- Tochigi dialect (Tochigi Prefecture)

- Chiba dialect (Chiba Prefecture)

Tōkai-Tōsan dialect

The Tōkai-Tōsan dialect is separated into three groups: Nagano-Yamanashi-Shizuoka, Echigo and Gifu-Aichi.

Nagano-Yamanashi-Shizuoka

- Nagano dialect or Shinshū dialect (Nagano Prefecture)

- Okushin dialect (northernmost area)

- Hokushin dialect (northern area)

- Tōshin dialect (eastern area)

- Chūshin dialect (central area)

- Nanshin dialect (southern area)

- Izu dialect (eastern Shizuoka Prefecture around the Izu Peninsula)

- Shizuoka dialect (central Shizuoka Prefecture)

- Enshū dialect (western Shizuoka Prefecture, formaly known as Tōtōmi Province)

- Kōshū dialect or Yamanashi dialect (Yamanashi Prefecture especially western area)

Echigo

- Niigata dialect (Niigata city)

- Nagaoka dialect (central Niigata Prefecture, around Nagaoka city)

- Jōetsu dialect (western Niigata Prefecture, around Jōetsu city)

- Uonuma dialect (southern Niigata Prefecture)

Gifu-Aichi

- Mino dialect (southern Gifu Prefecture, formaly known as Mino Province)

- Hida dialect (northern Gifu Prefecture, formaly known as Hida Province)

- Owari dialect (western Aichi Prefecture, formaly known as Owari Province)

- Chita dialect (along the Chita Peninsula)

- Nagoya dialect (centered around Nagoya)

- Mikawa dialect (eastern Aichi Prefecture, formaly known as Mikawa Province)

- West Mikawa

- East Mikawa

Western Japanese

The dialects of western Japan have some common features that are markedly different from Eastern Japanese including the standard Tokyo dialect; for example, "exist [human/animals]" oru instead of iru, the copula ja or ya instead of da, and the negative form -n as in ikan ("don't go") instead of -nai as in ikanai. Western Japanese was the prestige dialect when Kyoto was the capital, so some features are used in literary language and archaic expressions of modern standard Japanese.

Hokuriku dialect

Main article: Hokuriku dialectTypes of Hokuriku dialect:

- Kaga dialect (southern Ishikawa Prefecture, formerly known as Kaga Province)

- Kanazawa dialect (Kanazawa, Ishikawa)

- Noto dialect (northern Ishikawa Prefecture, formerly known as Noto Province)

- Toyama dialect or Etchū dialect (Toyama Prefecture)

- Fukui dialect (northern Fukui Prefecture)

- Sado dialect (Sado Island, Niigata Prefecture)

Kinki (Kansai) dialect

Main article: Kansai dialectKansai is the second most populated region in Japan after Kanto and the center of Japanese comedy, making Kansai dialect, especially that of Osaka, the most widely known non-standard dialect of Japanese. Kansai dialect is characterized as Kyoto-Osaka-type accent, strong vowel, copula ya, negative form -hen, etc.

- Kyoto dialect (southern Kyoto Prefecture, especially the city of Kyoto)

- Gosho dialect (old Kyoto Gosho dialect)

- Muromachi dialect (old merchant dialect in central area of the city of Kyoto)

- Gion dialect (geiko dialect of Gion)

- Osaka dialect (Osaka Prefecture, especially the city of Osaka)

- Semba dialect (old merchant dialect in the central area of the city of Osaka)

- Kawachi dialect (eastern Osaka Prefecture, formerly known as Kawachi Province)

- Senshū dialect (southern Osaka Prefecture, formerly known as Izumi Province)

- Kobe dialect (city of Kobe)

- Nara dialect or Yamato dialect (Nara Prefecture)

- Oku-yoshino dialect or Totsukawa dialect (southernmost Nara Prefecture such as Totsukawa village)

- Tamba dialect (central of Kyoto Prefecture, and eastern Hyōgo Prefecture, formerly known as Tamba Province)

- Maizuru dialect (city of Maizuru, Kyoto Prefecture)

- Banshū dialect (southwestern Hyōgo Prefecture, formerly known as Harima Province)

- Shiga dialect or Ōmi dialect (Shiga Prefecture)

- Wakayama dialect or Kishū dialect (Wakayama Prefecture and southern Mie Prefecture, formerly known as Kii Province)

- Mie dialect (mainly Mie Prefecture)

- Ise dialect (mid-northern Mie Prefecture, formerly known as Ise Province)

- Shima dialect (eastern Mie Prefecture, formerly known as Shima Province)

- Iga dialect (western Mie Prefecture, formerly known as Iga Province)

- Wakasa dialect (southern Fukui Prefecture, formerly known as Wakasa Province)

Chūgoku dialect

Chūgoku dialect is separated into two groups by copula.

- copula ja (じゃ) group (San'yō region)

- Aki dialect or Hiroshima dialect (western Hiroshima Prefecture, formerly known as Aki Province)

- Bingo dialect (eastern Hiroshima Prefecture, formerly known as Bingo Province)

- Fukuyama dialect (Fukuyama, Hiroshima)

- Okayama dialect (Okayama Prefecture)

- Yamaguchi dialect (Yamaguchi Prefecture)

- copula da (だ) group (eastern and western San'in region)

- Iwami dialect (western Shimane Prefecture, formerly known as Iwami Province)

- Inshū dialect or Tottori dialect (eastern Tottori Prefecture, formerly known as Inaba Province)

- Tajima dialect (northern Hyōgo Prefecture, formaly known as Tajima Province)

- Tango dialect (northernmost of Kyoto Prefecture, formerly known as Tango Province except Maizuru)

Although Kansai dialect uses copula ya (や), Chūgoku dialect uses ja (じゃ) or da (だ). Chūgoku dialect uses ken (けん) or kee (けえ) instead of kara (から) meaning because. ken is also used in Umpaku dialect, Shikoku dialect and some Kyūshū dialect. In addition, Chūgoku dialect uses -yoru (よる) in progressive aspect and -toru (とる) or -choru (ちょる) in perfect. For example, "Tarō wa benkyō shiyoru" (太郎は勉強しよる) means "Taro is studying", and "Tarō wa benkyō shitoru" (太郎は勉強しとる) means "Taro has studied" while standard Japanese speakers say "Tarō wa benkyō shiteiru" (太郎は勉強している) in both situations. -Choru is used mostly in Yamaguchi dialect.

Umpaku dialect

"Umpaku" means "Izumo and Hōki", central San'in region.

Types of Umpaku dialect include:

- Izumo dialect (eastern Shimane Prefecture, formaly known as Izumo Province)

- Yonago dialect (western Tottori Prefecture, formaly known as Hōki Province)

- Oki dialect (Oki islands of Shimane Prefecture)

Umpaku dialect, unique from other dialects of Chugoku region, is superficially resembles Tohoku dialects and is thus also called "Zuu zuu ben". It has neutralization of the high vowels "i" and "u".

The most representative expressions from Izumo-ben include dandan (だんだん) to mean thank you, chonboshi (ちょんぼし) or chokkoshi (ちょっこし) in place of sukoshi (少し), banjimashite (晩じまして) as a evening greeting and gosu (ごす) in place of kureru (くれる).

Shikoku dialect

Types of Shikoku dialect:

- Awa dialect or Tokushima dialect (Tokushima Prefecture)

- Sanuki dialect (Kagawa Prefecture)

- Iyo dialect (Ehime Prefecture)

- Tosa dialect or Kōchi dialect (Kōchi Prefecture)

- Hata Dialect (Hata district, westernmost of Kochi)

Shikoku dialect has many similarities to Chūgoku dialect in grammar. Shikoku dialect uses ken (けん) instead of kara (から), and よる in progressive aspect and とる or ちょる in the perfect. Some people in Kōchi Prefecture uses kin (きん),kini (きに), or ki (き) instead of けん, yoo (よー) or yuu(ゆう) instead of よる, and choo (ちょー) or chuu (ちゅう) instead of とる or ちょる.

The largest difference between Shikoku dialect and Chūgoku dialect is in pitch accent. Many dialects in Shikoku uses Kyoto-Osaka-type accent and similar to Kansai dialect, but Chūgoku dialect uses Tokyo-type accent.

Kyūshū

Hōnichi dialect

"Hōnichi" means "Buzen (eastern Fukuoka and northern Oita), Bungo (southern Oita) and Hyūga (Miyazaki)" in eastern Kyushu.

Sub-dialects of Hōnichi dialect include:

- Kitakyūshū dialect (Kitakyūshū, Fukuoka Prefecture)

- Ōita dialect (Ōita Prefecture except Hita)

- Miyazaki dialect (Miyazaki Prefecture)

Miyazaki dialect is most noted for its intonation, which is very different from that of Standard Japanese and other Hōnichi dialect. At times it can employ a pattern of intonation seemingly inverse to that of Standard Japanese. Miyazaki dialect shares with Hichiku and Satsugū dialects similarities such as: と (to) replacing the question particle の (no).

Hichiku dialect

"Hichiku" means "Hizen (Saga and Nagasaki), Higo (Kumamoto), Chikuzen (western Fukuoka) and Chikugo (southern Fukuoka)" in Northwestern Kyushu.

Types of Hichiku dialect include:

- Hakata dialect (western Fukuoka Prefecture, formaly known as Chikuzen Province, especially Hakatain Fukuoka City)

- Chikugo dialect (southern Fukuoka Prefecture, formaly known as Chikugo Province)

- Ōmuta dialect (Ōmuta city)

- Yanagawa dialect (Yanagawa city)

- Chikuhō dialect (central Fukuoka Prefecture such as Iizuka)

- Saga dialect (Saga Prefecture)

- Nagasaki dialect (Nagasaki Prefecture)

- Sasebo dialect (northern Nagasaki Prefecture around Sasebo)

- Hirado dialect (Hirado Island, west of Nagasaki Prefecture)

- Kumamoto dialect (Kumamoto Prefecture)

- Hita dialect (Hita, southwestern Oita Prefecture)

- Iki dialect (Iki Island of Nagasaki Prefecture)

- Tsushima dialect (Tsushima Island of Nagasaki Prefecture)

Hakata-ben is the dialect of the Hakata of Fukuoka City. Throughout Japan, Hakata-ben is famous, amongst many other idiosyncrasies, for its use of "-to?" as a question, e.g., "What are you doing?", realized in Standard Japanese as "nani o shite iru no?", is "nan ba shiyotto?" or "nan shitōtō?" in Hakata. Hakata-ben is also being used more often in Fukuoka in television interviews, where previously standard Japanese was expected.

Tsushima-ben is a Kyūshū dialect spoken within the Tsushima Island of Nagasaki Prefecture. Tsushima dialect includes several words unintelligible to speakers from the other parts of Japan because Tsushima-ben has borrowed several words from Korean due to historical international exchanges and the geographical proximity of Korea. However Tsushima-ben shares most of its basic words with those of other Kyushu dialects.

Korean loanwords in Tsushima dialect Tsushima dialect Korean derivation Standard Japanese English gloss ヤンバン

yanban양반(兩班)

yangban金持ち

kanemochiRich person

(Note that in Korean yangban is a Korean elite class)チング, チングィ

chingu, chingui친구(親舊)

chingu友達

tomodachiFriend トーマンカッタ

tōmankatta도망(逃亡)갔다

tomang gatta夜逃げ

yonigeEscaping at night (or running from debt)

(Note that the Korean source, tomang gatta, is actually a verbal phrase meaning "ran away; escaped")ハンガチ

hangachi한가지

hangajiひとつ

hitotsuOne (item)

(Note that the Korean word actually means "one kind, one type, a sort (of)")チョコマン

chokoman조그만

jogeuman小さい

chiisaiSmall バッチ

batchi바지

bajiズボン

zubonPants Satsugū dialect

"Satsugū" means "Satsuma (Western of Kagoshima) and Osumi (Eastern of Kagoshima)" in Southern Kyushu.

Types of Satsugū dialect include:

- Satsuma dialect

- Osumi dialect

- Morokata dialect (Southwesternmost of Miyazaki)

Satsuma-ben, the dialect of Satsuma area of Kagoshima prefecture, is often called "unintelligible" because of distinct conjugations of words, significantly different vocabulary and pronunciation. As the farthest place from Kyoto, it is likely that divergences in dialect were accumulated in Satsuma making it sound relatively distinct. For example, the yotsugana (ジ, ヂ, ズ, ヅ), which are pronounced as 2 different phonemes in most dialects, are 4 separate phonemes in the Kagoshima dialect. There are several different dialect regions within Kagoshima prefecture.

Hachijō Island

A small group of dialects are spoken in Hachijōjima and Aogashima, islands south of Tokyo.

Usually Hachijō Dialect is regarded as an independent "root branch" itself for its unique characteristics, especially the abundance of inherited ancient Eastern Japanese features, in spite of its small population. The dialect has quite a lot of phrases that have been otherwise lost in the rest of Japan. Such phrases include まぐれる "magureru" instead of the modern 気絶する "kizetsu suru".

Instead of referring to inanimate and animate objects differently with aru and iru respectively like the majority of the mainland, the Hachijō Dialect does not distinguish between the two and uses aru for both cases.

There are quite a few words that the dialect has that differ in meaning than what they are normally used for in the rest of Japan. Below are some of these words.[4]

Hachijō Dialect Standard Japanese Meaning yama hatake field¹ ureshi naru byōki ga naotte kuru to heal from an illness² kowai tsukareru to be tired³ gomi takigi firewood - ¹ Cf. standard yama "mountain"

- ² Cf. standard ureshiku naru "become happy"

- ³ Cf. standard kowai "to be tough/hard, to be stubborn"

Ryūkyū

Main article: Ryukyuan languagesThere is general agreement among linguists that the speech varieties of the Ryukyu Islands (the islands of Okinawa Prefecture and some of the islands of Kagoshima Prefecture) form a separate branch of the Japonic family known as the Ryukyuan languages.

There is great diversity within Japanese, and even greater diversity among the Ryukyuan languages. Many native speakers from one area of Japan can find the speech of another area virtually unintelligible. There has also developed in the Ryūkyūs a dialect called Okinawan Japanese which is close to standard Japanese, but which is influenced by Ryukyuan languages. For example, "deeji" may be said sometimes instead of "taihen", or "haisai" instead of "konnichiwa".

See also

- Yotsugana, the differing pronunciation of the ジ, ヂ, ズ, and ヅ kana in different regions of Japan.

References

- ^ Johnston, Eric, "Dialect-rife Japan can be tongue-twisting", FYI, The Japan Times, 13 November 2007, p. 3, retrieved 24 December 2010.

- ^ Satoh Kazuyuki (佐藤和之); Yoneda Masato (米田正人) (1999) (in Japanese). Dōnaru Nihon no Kotoba, Hōgen to Kyōtsūgo no Yukue. Tōkyō: The Taishūkan Shoten (大修館書店). ISBN 978-4469212440.

- ^ Takashi Kobayashi (小林隆); Kōichi Shinozaki (篠崎晃一), Takuichirō Ōnishi (大西拓一郎) (1996) (in Japanese). Hōgen no Genzai. Tōkyō: The Meiji Shoin (明治書院). ISBN 978-4625420979.

- ^ http://www008.upp.so-net.ne.jp/ohwaki/hougen.htm/

External links

- 日本語情報資料館 (The Japanese information library) (Japanese)

- 日本言語地図 (The linguistic maps of Japan)

- 全国方言談話データベース (The conversation database of dialects in all Japan)

- 方言談話資料 (The conversation data of dialects)

- 方言録音資料シリーズ (The recording data series of dialects)

- Dialectological Circle of Japan (English)

- Daniel Long's Japanese Linguistics Research Site (English)

- 方言研究の部屋 (The room of dialect) (Japanese)

- ふるさとの方言 (The dialects of Hometown) (Japanese)

- 全国方言WEB ほべりぐ (All Japan Dialects WEB HOBERIGU) (Japanese)

- Kansai Dialect Self-study Site for Japanese Language Learner (English)

- Japanese Dialects (English)

Japanese language Stages Old Japanese · Early Middle Japanese · Late Middle Japanese · Early Modern Japanese · Modern JapaneseDialects Literature Writing system OrthographyGrammar and

vocabularyJapanese grammar · Verb conjugations and adjective declensions · Consonant and vowel verbs · Pronouns · Adjectives · Possessives · Particles · Topic marker · Counter words · Numerals · Native words (yamato kotoba) · Sino-Japanese vocabulary · Loan words (gairaigo) · Honorific speech · Honorifics · Gender differencesPhonology Romanization Categories:

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.