- Conan the Barbarian (1982 film)

-

Conan the Barbarian

Main promotional art by Renato Casaro for the filmDirected by John Milius Produced by Buzz Feitshans

Raffaella De LaurentiisWritten by John Milius

Oliver StoneBased on Conan the Barbarian stories by

Robert E. HowardStarring Arnold Schwarzenegger

James Earl JonesMusic by Basil Poledouris Distributed by Universal Pictures (United States)

20th Century Fox (others)Release date(s) March 16, 1982 (Spain)

May 14, 1982 (United States)Running time 129 minutes Country United States Language English Budget $17.5–20 million Box office $100 million Conan the Barbarian is a 1982 fantasy film. It is based on the stories by Robert E. Howard, a pulp fiction writer of the 1930s, about the adventures of the eponymous character in a fictional pre-historic world of dark magic and savagery. The film adaptation was written and directed by John Milius, and produced by Raffaella De Laurentiis and Buzz Feitshans. Basil Poledouris provided the music. The film stars Arnold Schwarzenegger, and tells the story of a young barbarian who seeks vengeance for the death of his parents. The target of his hatred is Thulsa Doom, the leader of a snake cult.

Ideas for a film about Conan were proposed as early as 1970. A concerted effort by Edward R. Pressman and Edward Summer to produce the film started in 1975. It took them two years to obtain the film rights, after which they recruited Schwarzenegger for the lead role and Oliver Stone to draft a script. Pressman lacked capital for the endeavor, and in 1979, after having his proposals for investments rejected by the major studios, he sold the project to Raffaella's father, Dino. Milius was appointed as director and he rewrote Stone's script. The final screenplay integrated scenes from Howard's stories and from films such as Kwaidan and Seven Samurai.

Filming took place in Spain over five months, in the regions around Madrid and Almería. The sets, designed by Ron Cobb, were based on Dark Age cultures and Frank Frazetta's paintings of Conan. Milius eschewed optical effects, preferring to realize his ideas with mechanical constructs and optical illusions. Schwarzenegger performed most of his own stunts and two types of swords, costing $10,000 each, were forged for his character. The editing process took over a year and several violent scenes were cut.

Conan was a commercial success for its backers, grossing more than $100 million at box-offices around the world, though the revenue fell short of the level that would qualify the film as a blockbuster. Academics and critics interpreted the film as advancing the themes of fascism or individualism, and the fascist angle featured in most of the criticisms of the film. Critics also panned Schwarzenegger's acting and the film's violent scenes. Despite the criticisms, Conan was popular with young males. The film earned Schwarzenegger worldwide recognition. Conan has been frequently released on home media, the sales of which had increased the film's gross to more than $300 million by 2007.

Contents

Plot

Opening narrationBetween the time when the oceans drank Atlantis and the rise of the sons of Aryus, there was an age undreamed-of. And unto this Conan, destined to bear the jeweled crown of Aquilonia upon a troubled brow. It is I, his chronicler, who alone can tell thee of his saga. Let me tell you of the days of high adventure.

Wizard of the Mounds[1]Conan the Barbarian is a film about a young barbarian's quest to avenge his parents' deaths. The story is set in the fictional Hyborian Age, thousands of years before the rise of modern civilization.[2] The film opens with the words, "That which does not kill us makes us stronger", a paraphrasing of Friedrich Nietzsche,[nb 1] on a black screen followed by a voice-over that establishes the film as the story of Conan's origin.[1][4] "A burst of drums and trumpets" accompanies the forging of a sword,[2][nb 2] after which the scene shifts to a mountain top, where the swordsmith tells his young son Conan about the Riddle of Steel, an aphorism on the importance of the metal to their people,[6][7] the Cimmerians.[8]

The Cimmerians are massacred by a band of warriors led by Thulsa Doom. Conan's father is killed by dogs, and his sword is taken by Doom to decapitate Conan's mother. The children are taken into slavery; Conan is chained to a large mill, the Wheel of Pain. Years of pushing the huge grindstone build up his muscles. His master trains him to be a gladiator, and after winning many pit fights, Conan is freed. As he wanders the world, he encounters a witch and befriends Subotai, a thief and archer.[9][10]

Following the witch's advice, Conan and Subotai go to Shadizar, in the land of Zamora, to seek out Doom.[11] They meet Valeria, a female brigand, who becomes Conan's lover. They burgle the Tower of Serpents, stealing a large jewel—the Eye of the Serpent—and other valuables from Doom's snake cult. After escaping with their loot, the thieves celebrate and end up in a drunken stupor. The city guards capture them and bring them to King Osric. He requests they rescue his daughter, who has joined Doom's cult. Subotai and Valeria do not want to take up the quest; Conan, motivated by his hatred for Doom, sets off alone to the villain's Temple of Set.[12]

Disguised as a priest, Conan infiltrates the temple, but he is discovered, captured, and tortured. Doom lectures him on the power of flesh, which he demonstrates by compelling a girl to leap to her death. He then orders Conan crucified on the Tree of Woe. The barbarian is on the verge of death when he is discovered by Subotai and brought to the Wizard of the Mounds, who lives on a burial site for warriors and kings.[13][14] The wizard summons spirits to heal Conan[15] and warns that they will "extract a heavy toll", which Valeria is willing to pay. These spirits also try to abduct Conan, but he is restored to health after Valeria and Subotai fend them off.[13]

Subotai and Valeria agree to complete Osric's quest with Conan and they infiltrate the Temple of Set. As the cult indulges in a cannibalistic orgy, the thieves attack and flee with the princess. Valeria is mortally wounded by Doom after he shoots a stiffened snake at her. She dies in Conan's arms and is cremated at the Mounds, where Conan prepares with Subotai and the wizard to battle Doom. By using booby-traps and exploiting the terrain, they manage to kill Doom's soldiers. Valeria reappears for a brief moment as a Valkyrie to save Conan from a mortal blow.[7][16] Conan recovers his father's sword during the fight, although its blade is broken. After losing his men, Doom shoots a stiffened snake at the princess. Subotai blocks the shot and the villain flees to his temple.[17]

Conan sneaks back into the temple where Doom stands at the top of a long stairway, addressing the members of his cult. Conan confronts Doom, who attempts to mesmerize him, but the barbarian resists and uses his father's sword to behead his nemesis. After throwing Doom's head down the stairs, Conan burns down the temple.[17] He returns the princess, and the final scene shows him as an old king; the narration says his road to the throne is another tale.[18]

Characters

The character, Conan, and the world of Hyboria were based on the creations of pulp-fiction writer Robert E. Howard from the 1930s. Published in Weird Tales, his series about the barbarian was popular with the readership; the barbarian's adventures in a savage and mystical world, replete with gore and brutal slayings, satisfied the reader's fantasies of being a "powerful giant who lives by no rules but his own".[19] From the 1960s, Conan gained a wider audience as novels about him, written in imitation of Howard's style by L. Sprague de Camp and Lin Carter, were published. Frank Frazetta's cover art for these novels cemented Conan's image as a "virile, axe-wielding, fur-bearing, cranium-smashing barbarian".[20] John Milius, the film's director, intended the film's Conan to be "a Northern European mythic hero".[21] Danny Peary described Conan as "muscular, majestic, brainy, yet with ambivalent scruples".[22] Don Herron, a scholar on Howard and his stories, disagreed, noting that the personality of Conan in the film differs greatly from that of the literature. The Conan in the books detests restrictions to his freedom and would have resisted slavery in a violent fashion, whereas the film version accepts his fate and has to be freed.[23] Robert Garcia's review of the film in his American Fantasy magazine states that "this Conan is less powerful, less talkative, and less educated than Howard's".[1]

The female lead, Valeria, has her roots in two strong female characters from Howard's Conan stories.[24] Her namesake was Conan's companion in "Red Nails", while her personality and fate were based on those of Bêlit, the pirate queen in "Queen of the Black Coast".[25] According to Kristina Passman, an assistant professor of classical languages and literature, the film's Valeria is a perfect archetype of the "good" Amazon character, a fierce but domesticated female warrior, in cinema.[26][27] Rikke Schubart, a film scholar, said Valeria is a "good" Amazon because she is tamed by love and not because of any altruistic tendencies.[28] Valeria's prowess in battle matches that of Conan and she is also depicted as his equal in behavior and status. The loyalty and love she displays for Conan makes her more than a dear companion to him;[29] she represents his "possibilities of human happiness".[30] Her sacrifice for Conan and her brief return from death act out the heroic code, illustrating that self-sacrificing heroism brings "undying fame".[29] Valeria's name is not spoken in the film; the only scene where she was named, her self-introduction, was cut.[31]

Milius based Conan's other companion, Subotai, on Genghis Khan's main general, Subotai, rather than on any of Howard's characters.[32] According to film critic Roger Ebert, Subotai fulfills the role of a "classic literary type—the Best Pal."[33] He helps the barbarian to kill a giant snake and cuts him down from crucifixion; the thief also cries for his companion during Valeria's cremation, with the explanation that "being a Cimmerian, [Conan] will not cry for himself."[34]

Conan's enemy, Thulsa Doom, is an amalgamation of two of Howard's creations. He takes his name from the villain in Howard's Kull of Atlantis series of stories, but is closer in character to Thoth-Amon, Conan's nemesis in "The Phoenix on the Sword".[21] The Doom in the film reminded critics of Jim Jones, a cult leader whose hold on his followers was such that hundreds of them obeyed his orders to commit suicide.[33][35] Milius said his research on the ancient orders of the Hashishim and the Thuggee was the inspiration for Doom's snake cult.[36]

Production

From the 1970s, licensing issues had stood in the way of producing film versions of the Conan stories. Lancer Books, which had acquired the rights in 1966,[37][38] went into receivership, and there were legal disputes over their disposition of the publishing rights, which ultimately led to them being frozen under injunction.[37][39] Edward Summer suggested Conan as a potential project to Edward R. Pressman in 1975, and after being shown the comics and Frazetta's artwork, Pressman was convinced.[40] It took two years to secure the film rights.[37] The two main parties involved in the lawsuit, Glenn Lord and de Camp, formed Conan Properties Incorporated to handle all licensing of Conan-related material, and Pressman was awarded the film rights shortly afterwards.[41] He spent more than $100,000 in legal fees to help resolve the lawsuit, and the rights cost him another $7,500.[42]

The success of Star Wars in 1977 increased Hollywood's interest in producing films that portray "heroic adventures in supernatural lands of fables".[43] The film industry's attention was drawn to the popularity of Conan among young male Americans, who were buying reprints of the stories with Frazetta's art and adaptations by Marvel Comics.[44] John Milius first expressed interest in directing a film about Conan in 1978 after completing the filming of Big Wednesday, according to Buzz Feitshans, a producer who frequently worked with Milius.[45] Milius and Feitshans approached Pressman, but differences over several issues stopped discussions from going further.[45]

Oliver Stone joined the Conan project after Paramount Pictures offered to fund the film's initial $2.5 million budget if a "name screenwriter" was on the team.[46] After securing Stone's services, Pressman approached Frank Frazetta to be a "visual consultant" but they failed to come to terms.[47] The producer then engaged Ron Cobb, who had just completed a set design job on Alien (1979).[48] Cobb made a series of paintings and drawings for Pressman before leaving to join Milius on another project.[49]

The estimates to realize Stone's finished script ran to $40 million; Pressman, Summer, and Stone could not convince a studio to finance their project.[46] Pressman's production company was in financial difficulties and to keep it afloat, he borrowed money from the bank.[50] The failure to find a suitable director was also a problem for the project. Stone and Joe Alves, who was the second unit director for Jaws, were considered as possible co-directors, but Pressman said it "was a pretty crazy idea and [they] didn't get anywhere with it".[51] Stone also said that he asked Ridley Scott, who had finished directing Alien, to take up the task but was rejected.[52]

Cobb showed Milius his work for Conan and Stone's script which, according to him, re-ignited Milius's interest; the director contacted Pressman,[49] and they came to an agreement: Milius would direct the film if he was allowed to modify the script.[53] Milius was known in the film industry for his macho screenplays for Dirty Harry (1971) and Magnum Force (1973).[54][55] He was, however, contracted to direct his next film for Dino De Laurentiis,[45] an influential producer in the fantasy film industry.[56] Milius raised the idea of taking on Conan with Laurentiis,[45] and, after a year of negotiations, Pressman and Laurentiis agreed to co-produce.[42] Laurentiis took over the financing and production and Pressman gave up all claims to the film's profits, though he retained approval over changes to the script, cast and director.[42] Laurentiis assigned the responsibility for production to his daughter, Raffaella, and Feitshans.[37] Milius was formally appointed as director in early 1979, and Cobb was named as the production designer.[57] Laurentiis convinced Universal Pictures to become the film's distributor for the United States.[58] The studio also contributed to the production budget of $17.5 million and prepared $12 million to advertise the film.[59]

Casting

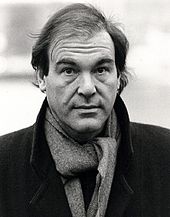

Ed Pressman and his associates considered Arnold Schwarzenegger (1984 photograph) the embodiment of Conan the Barbarian.

Ed Pressman and his associates considered Arnold Schwarzenegger (1984 photograph) the embodiment of Conan the Barbarian.

While they were working to secure the film rights, Pressman and Summer were also contemplating the lead role. Summer said they considered Charles Bronson, Sylvester Stallone, and William Smith—all of whom had played tough figures,[60] but in 1976, the two producers watched a rough cut of the bodybuilding film Pumping Iron, and agreed Arnold Schwarzenegger was perfect for the role of Conan.[61] According to Schwarzenegger, Pressman's "low-key" approach and "great inner strength" convinced him to join the project.[62] Paul Sammon, writer for Cinefantastique, said that the former champion bodybuilder was practically the "living incarnation of one of Frazetta's paperback illustrations".[47] Schwarzenegger was paid $250,000 and placed on retainer;[63] the terms of the contract restricted him from starring in other sword and sorcery films.[64] Schwarzenegger said Conan was his biggest opportunity to establish himself in the entertainment industry.[65]

Thanks to Pressman's firm belief in him, Schwarzenegger retained the role of Conan even after the project was effectively sold to Laurentiis.[42] Milius wanted a more athletic look on his lead actor, so Schwarzenegger undertook an 18 month training regime before shooting began; aside from running and lifting weights, his routines included rope climbing, horseback riding, and swimming. He slimmed down from 240 to 210 pounds (110 to 95 kg).[66] Aside from Conan, two other substantial roles were also played by novice actors. Subotai was Gerry Lopez, a champion surfer, whose only major acting experience was playing himself in Milius's Big Wednesday.[25] Schwarzenegger stayed at Lopez's home for over a month before the start of filming so they could rehearse their roles and build a rapport.[67] Sandahl Bergman, a dancer who had bit parts in several theater productions and films, played Valeria. She was recommended to Milius by Bob Fosse, who had directed her in All That Jazz (1979), and was accepted after reading for the part.[68][69]

Milius said the actors were chosen because their appearances and personae fitted their roles.[70] He wanted actors who would not have any preconceived notions to project into their roles.[71] Although Milius had reservations when he witnessed the first few takes of the novices at work, he put faith in them improving their skills on the job and altered the script to fit their abilities.[72] Schwarzenegger had studied for weeks in 1980 under Robert Easton, a voice coach for several Hollywood stars, to improve his speech.[73] His first line in the film was a paraphrasing of Mongol emperor Genghis Khan's speech about the good things in life and the actor delivered it with a heavy Austrian-accent; critics later described what they heard as "to crush your enemies—see dem [them] driven before you, and to hear the lamentations of dair vimen [their women]".[2][73][74][nb 3] Subsequently, Schwarzenegger underwent intensive speech training with Milius. Each of his later longer speeches was rehearsed at least forty times.[74] Lopez's lines were also an issue: although Milius was satisfied with Lopez's work, the surfer's lines were redubbed by stage actor Sab Shimono for the final cut. A source close to the production said this was done because Lopez failed to "[maintain] a certain quality to his voice."[77]

Sean Connery and John Huston were considered for the other roles.[25][78] James Earl Jones and Max von Sydow were, according to Milius, hired with the hope that they would inspire Schwarzenegger, Bergman, and Lopez.[71] Jones was an award-winning veteran of numerous theater and cinema productions.[79] Von Sydow was a Swedish actor of international renown.[80] The role of Thulsa Doom was offered to Jones while he was considering applying for the role of Grendel in an upcoming feature based on James Gardner's eponymous novel; after learning it was an animation, Jones read Conan's script and accepted the part of Doom.[81] When filming started on Conan, Jones was also starring in a Broadway play—Athol Fugard's A Lesson to Aloes. He and the film crew coordinated their schedules to allow him to join the play's remaining performances.[82] Jones took an interest in Schwarzenegger's acting, often giving him pointers on how to deliver his lines.[74]

The Japanese actor Mako Iwamatsu, known professionally as "Mako", was brought onto the project by Milius for his experience;[71] he had played roles in many plays and films and had been nominated for an Academy and a Tony Award.[83] In Conan, Mako played the Wizard of the Mounds and voiced the film's opening speech.[1] William Smith, although passed over for the lead role, was hired to play the barbarian's father.[25] Doom's two lieutenants were played by Sven-Ole Thorsen, a Danish bodybuilder and karate master, and Ben Davidson, a former American-football player with the Oakland Raiders.[68] Milius hired more than 1,500 extras in Spain.[14] Professional actors from the European film industry were also hired: Valerie Quennessen was chosen to play Osric's daughter, Jorge Sanz acted as the nine-year-old version of Conan, and Nadiuska played his mother.[84]

Script writing

The drafting of a story for a Conan film started in 1976; Summer conceived a script with the help of Roy Thomas,[46] a writer who had created and edited several storylines for Marvel's Conan comic series.[44] Summer and Thomas's tale, in which Conan would be employed by a "dodgy priest to kill an evil wizard", was largely based on Howard's "Rogues in the House". Their script was abandoned when Oliver Stone joined the project.[85] Stone was, at this time, going through a period of addiction to cocaine and depressants. His screenplay was written under the influence of the drugs[86] and the result was what Milius called a "total drug fever dream", albeit an inspirational one.[87] According to Schwarzenegger, Stone completed a draft by early 1978.[88] Taking inspiration from Howard's "Black Colossus" and "A Witch Shall be Born", Stone proposed a story, four hours long,[89] in which the hero champions the defense of a princess's kingdom. Instead of taking place in the distant past, Stone's story is set in a post-apocalyptic future where Conan leads an army in a massive battle against a horde of 10,000 mutants.[54]

When Milius was appointed as director, he took over the task of writing the screenplay.[90] Although listed as a co-writer, Stone said Milius did not incorporate any of his suggestions into the final story.[91] Milius discarded the latter half of Stone's story.[92] He retained several scenes from the first half, such as Conan's crucifixion ordeal, which was taken straight out of "A Witch Shall be Born", and the climbing of the Tower of Serpents, which was derived from "The Tower of the Elephant".[93] One of Milius' original changes was to extend Stone's brief exposition of Conan's youth—the raid on the Cimmerian village—into his teens with the barbarian's enslavement at the Wheel of Pain and training as a gladiator.[55] Milius also added ideas gleaned from other films. The Japanese supernatural tale of "Hoichi the Earless", as portrayed in Masaki Kobayashi's Kwaidan (1965), inspired the painting of symbols on Conan's body and the swarm of ghosts during the barbarian's resurrection,[15] and Akira Kurosawa's Seven Samurai (1954) influenced Milius's vision of Conan's final battle against Doom's men.[19] Milius also included scenes from post-Howard stories about Conan; the barbarian's discovery of a tomb during his initial wanderings and acquisition of a sword within were based on de Camp and Carter's "The Thing in the Crypt".[21] According to Derek Elley, Variety's resident film critic, Milius's script, with its original ideas and references to the pulp stories, was faithful to Howard's ideals of Conan.[94]

Filming

Original introduction in the filmKnow, O Prince; that between the years when the oceans drank Atlantis and the rise of the Sons of Aryas, there was an Age undreamed of ... Hither came I, Conan, a thief, a reaver, a slayer, to tread jeweled thrones of the earth beneath my feet. But now my eyes are dim. Sit on the ground with me, for you are but the leavings of my age. Let me tell you of the days of high adventure.

King Conan[95]Filming started at England's Shepperton Studios in October 1980, with Schwarzenegger, made up to look like Conan as a king in his old age, reading an excerpt from "The Nemedian Chronicles", which Howard had penned to introduce his Conan stories. This footage was initially intended to be a trailer but Milius decided to use it as the opening sequence of the film instead.[96] According to Cobb, Laurentiis and Universal Pictures were concerned about Schwarzenegger's accent, so Milius compromised by moving the sequence to the end.[97][18]

The initial location for principal photography was Yugoslavia, but because of concerns over the country's stability after the death of its head of state, Josip Broz Tito, and the fact that the Yugoslavian film industry proved ill-equipped for large-scale film production, the producers elected to move the project to Spain, which was cheaper and where resources were more easily available. It took several months to relocate;[98] the crew and equipment arrived in September,[99] and filming started on January 7, 1981.[57] The producers allocated $11 million for production in Spain,[100] of which approximately $3 million was spent on building 49 sets.[101] The construction workforce numbered from 50 to 200; artists from England, Italy, and Spain were also recruited.[102]

A large warehouse 20 miles (32 km) outside Madrid served as the production's headquarters,[98] and it also housed most of the interior sets for the Tower of Serpents and Doom's temple;[103] a smaller warehouse was leased for other interior sets.[84] The remaining interiors for the Tower of Serpents were constructed in an abandoned hangar at Torrejón Air Base.[14] A full-scale, 40 feet (12 m) version of the tower was built in the hangar; this model was used to film Conan and his companion's climb up the structure.[14]

The crew filmed several exterior scenes in the countryside near Madrid;[84] the Cimmerian village was built in a forest near the Valsaín ski resort, south of Segovia. Approximately one million pesetas ($12,084)[nb 4] worth of marble shavings were scattered on the ground to simulate snow.[105] Conan's encounter with the witch and Subotai was shot among the Ciudad Encantada rock formations in the province of Cuenca.[11] Most outdoor scenes were shot in the province of Almería,[84] which offered a semi-arid climate, diverse terrain (deserts, beaches, mountains), and Roman and Moorish structures that could be adapted for many settings.[106]

Conan's crucifixion was filmed in March 1981 among the sand dunes on the southeastern coast of Almería. The Tree of Woe was layers of plaster and Styrofoam applied onto a skeleton of wood and steel. It was mounted on a turntable, allowing it to be rotated to ensure the angle of the shadows remained consistent throughout three days of filming. Schwarzenegger sat on a bicycle seat mounted in the tree while fake nails were affixed to his wrists and feet.[107] The scene in which Valeria and Subotai fought off ghosts to save Conan and the final battle with Doom's forces were filmed in the salt marshes of Almerimar. "Stonehenge-like ruins" were erected and sand piled into mounds that reached 9 meters (30 ft).[108] The changes to the landscape attracted protests from environmentalists and the producers promised to restore the site after filming was completed.[109]

The Temple of Set was built in the mountains, more than 12 kilometers (7.5 mi) west of the city of Almería. The structure was 50 meters (160 ft) long and 22 meters (72 ft) high. It was the most expensive of the sets, costing $350,000, and built out of various woods, lacquers, and tons of concrete. Its stairway had 120 steps.[110] Milius and his crew also filmed at historical sites and on sets from previous films. Scenes of a bazaar were filmed at the Moorish Alcazaba of Almería, which was dressed to give it a fictional Hyborian look.[11][111] Shadizar was realized at a pre-existing film set in the Almerían desert; the fort used for the filming of El Condor (1970) refurbished as an ancient city.[11]

It was expensive to build large sets,[112] and Milius did not want to rely on optical effects and matte paintings (painted landscapes). The crew instead adopted miniature effect techniques (playing on perspective) to achieve the illusion of size and grandeur for several scenes. Scale models of structures were constructed by Emilio Ruiz and positioned in front of the cameras so that they appeared as full-sized structures on film; using this technique the Shadizar set was extended to appear more than double its size.[113] Ruiz built eight major miniature models,[114] including a 4 feet (1.2 m) high palace and a representation of the entire city of Shadizar that spanned 120 square feet (11 m2).[14]

An academic commented that the Tree of Woe resembled a prop from a 1876 staging of Richard Wagner's Die Walküre.

An academic commented that the Tree of Woe resembled a prop from a 1876 staging of Richard Wagner's Die Walküre.

Cobb's direction for the sets was to "undo history", "to invent [their] own fantasy history", and yet maintain a "realistic, historical look".[115] Eschewing the Greco-Roman imagery used heavily in the sword-and-sandal films of the 1960s,[57] he realized a world that was an amalgamation of Dark Age cultures, such as the Mongols and the Vikings.[94] Several scenarios paid homage to Frazetta's paintings of Conan, such as the "half-naked slave girl chained to a pillar, with a snarling leopard at her feet," at the snake cult's orgy.[116] David Huckvale, a lecturer at the Open University and broadcaster for BBC Radio, said the designs of the Tree of Woe and the costumes appeared very similar to those used in Richard Wagner's Ring of the Nibelung operas at the Bayreuth Festspielhaus in 1876.[117] Principal photography was completed in the middle of May 1981.[118] The film crews burned down the Cimmerian village and the Temple of Set after completing filming on each set.[71][119]

Stunts and swords

Several action scenes in Conan were filmed with a "mini-jib" (a remote-controlled electronic camera mounted on a motorized lightweight crane) that Nick Allder, the special effects supervisor, had devised when he worked on Dragonslayer (1981).[120] The stunts were coordinated by Terry Leonard, who had worked on many films, including Milius's previous projects and Steven Spielberg's Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981).[49][121] Leonard said that Schwarzenegger, Bergman, and Lopez performed most of their own stunts, including the fights.[101]

The three actors were given martial arts training ahead of filming. From August 1980,[98] they were tutored by Kiyoshi Yamazaki, a karate black belt and master swordsman,[122] who drilled them in sword-fighting styles that were meant to make them look proficient in using their weapons.[123] They practiced each move in a fight at least 15 times before filming.[124] Yamazaki advised Leonard on the choreography of the sword fights and had a cameo role as one of Conan's instructors.[98]

Tim Huchthausen, the prop maker, worked with swordsmith Jody Samson to create the sturdy weapons Milius thought necessary.[125] Particular attention was paid to two swords wielded by Conan: his father's sword ("Master's sword") and the blade he finds in a tomb ("Atlantean sword"). Both weapons were realized from Cobb's drawings. Their blades were hand ground from carbon steel and heat treated and left unsharpened.[126] The hilts and pommels were sculpted and cast through the lost-wax process; inscriptions were added to the blades via electrical discharge machining.[127] Samson and Huchthausen made four Master's and four Atlantean swords, at a cost of $10,000 per weapon.[5][125] Copies of the Atlantean sword were struck and given to members of the production.[125]

Samson and Huchthausen agreed the weapons were heavy and unbalanced, and thus unsuitable for actual combat;[5][125] Lighter versions made of aluminum, fiberglass, and steel were struck in Madrid; these 3 pounds (1.4 kg) copies were used in the fight scenes.[31][125] According to Schwarzenegger, the heavy swords were used in close-up shots.[128] The other weapons used in the film were not as elaborate; Valeria's tulwar was ground out from an aluminum sheet.[129]

The copious amounts of blood spilled in the fight scenes came from bags of fake blood strapped to the performers' bodies. Animal blood gathered from slaughterhouses was poured onto the floor to simulate puddles of human blood.[130] Most of the times trick swords made from fiberglass were used when the scene called for a killing blow.[131] Designed by Allder, these swords could also retract their blades, and several sprayed blood from their tips.[101] Although the swords were intended to be safer alternatives to metal weapons, they could still be dangerous: in one of the fights, Bergman sparred with an extra who failed to follow the choreography and sliced open her finger.[131]

Accidents also happened in stunts that did not involve weapons. A stuntman smashed his face into a camera while riding a horse at full gallop,[132] and Schwarzenegger was attacked by one of the trained dogs.[133] The use of live animals also raised concerns about cruelty; the American Humane Association placed the film on its "unacceptable list". The transgressions listed by the association included the kicking of a dog, the striking of a camel, and the tripping of horses.[134]

Mechanical effects

Carlo De Marchis, the special make-up effects supervisor, and Colin Arthur, former Studio Head of Madame Tussauds, were responsible for the human dummies and fake body parts used in the film.[11][135] The dummies inflated crowd numbers and stood in as dead bodies,[101] while the body parts were used in scenes showing the aftermath of fights and the cult's cannibalistic feast.[136] In Thulsa Doom's beheading scene Schwarzenegger hacked at a dummy and pulled a concealed chain to detach its head.[77] The decapitation of Conan's mother was more complex: a Plexiglas shield between Jones and Nadiuska stopped his sword as he swung at her and an artificial head then dropped into the camera's view. A more elaborate head was used for the close-up shots; this prop spurted blood and the movements of its eyes, mouth, and tongue were controlled by cables hidden beneath the snow.[137]

Allder created a $20,000 36 feet (11 m) mechanical snake for the fight scene in the Tower of Serpents. The snake's body had a diameter of 2.5 feet (0.76 m), and its head was 2.5 feet (0.76 m) long and 2 feet (0.61 m) wide. Its skeleton was made from duralumin (an alloy used in aircraft frames) and its skin was vulcanized foam rubber. Controlled by steel cables and hydraulics, the snake could exert a force between 3.5 and 9 tons. Another two snakes of the same dimensions were made: one for stationary shots and one for decapitation by Schwarzenegger.[138] To create the scene at the Tree of Woe the crew tethered live vultures to the branches, and created a mechanical bird for Schwarzenegger to bite. The dummy bird's feathers and wings were from a dead vulture, and its control mechanisms were routed inside the false tree.[139]

According to Sammon, "one of the greatest special effects in the film [was] Thulsa Doom's onscreen transformation into a giant snake".[101] It involved footage of fake body parts, live and dummy snakes, miniatures, and other camera tricks combined into a flowing sequence with lap dissolve. After Jones was filmed in position, he was replaced by a hollow framework with a rubber mask that was pushed from behind by a snake head-shaped puppet to give the illusion of Doom's facial bones changing. The head was then replaced with a 6 feet (1.8 m) mechanical snake; as it moved outwards, a crew member pressed a foot pedal to collapse the framework. For the final part of the sequence, a real snake was filmed on a miniature set.[140]

Optical effects

There were few optical effects in Conan the Barbarian. Milius professed ambivalence to fantasy elements, preferring a story that showcases accomplishments realized through one's own efforts without reliance on the supernatural. He also said that he followed the advice of Cobb and other production members on the matters of special effects.[70][141] Peter Kuran's Visual Concepts Engineering (VCE) effects company was engaged in October 1981 to handle post-production optical effects for Conan. VCE had previously worked on films such as Raiders of the Lost Ark and Dragonslayer. Among their tasks for Conan were adding glint and sparkle to The Eye of the Serpent and Valeria's Valkyrie armor.[142] Not all of VCE's work made it to the final print: the flames of Valeria's funeral pyre were originally enhanced by the company but were later restored to the original version.[132]

For the scene in which Valeria and Subotai had to fend off ghosts to save Conan's life, the "boiling clouds" were created by George Lucas's Industrial Light and Magic, while VCE was given the task of creating the ghosts. Their first attempt—filming strips of film emulsion suspended in a vat of a viscous solution—elicited complaints from the producers who thought the resulting spirits looked too much like those in a scene from Raiders of the Lost Ark, so VCE turned to animation to complete the task. First, they drew muscular warriors in ghostly forms onto cels and printed the images onto film with an Oxberry animation stand and contact printer. The Oxberry was fitted with a used lens that introduced lens flares to the prints; VCE's intention with using the old lens was to make the resultant images of the ghosts seem as if they were of real-life objects filmed with a camera. The final composite was produced by passing the reels of film for the effects and the live-action sequences through a two-headed optical printer and capturing the results with a camera.[142]

Music

Milius recruited his friend, Basil Poledouris, to produce the score for Conan; they had a successful collaboration on Big Wednesday.[143][144] The film industry's usual practice was to contract a composer to start work after the main scenes had been filmed, but Milius hired Poledouris before principal photography had started; the composer was given the opportunity to compose the film's music based on the initial storyboards and to modify it throughout filming before recording the score near the end of production.[145] Poledouris made extensive use of Musync, a music-editing software, to modify the tempo of his compositions and synchronize them with the action in the film. The software helped make his job easier and faster; it could automatically adjust the tempo when the user changed the positioning of a beat. Poledouris would, otherwise, have had to conduct the orchestra and adjust his compositions on the fly.[146] Conan is the first film to list Musync in its credits.[147]

Milius and Poledouris exchanged ideas throughout production, working out themes and "emotional tones" for each scene.[148] According to Poledouris, Milius envisioned Conan as an opera with little or no dialog;[149] Poledouris composed enough musical pieces for most (approximately two hours) of the film.[150] This was his first large-scale orchestral score,[150] and a characteristic of his work here was that he frequently slowed down the tempo of the last two bars (segments of beats) before switching to the next piece of music.[151] Poledouris said the score uses a lot of fifths as its most primitive interval; thirds and sixths are introduced as the story progresses.[152] The composer visited the film sets several times during filming to see the imagery his music would accompany. After principal photography was completed, Milius sent him two copies of the edited film: one without music, and the other with its scenes set to works by Richard Wagner, Igor Stravinsky, and Sergei Prokofiev, to illustrate the emotional overtones he wanted.[153]

Poledouris said he started working on the score by developing the melodic line—a pattern of musical ideas supported by rhythms. The first draft was a poem sung to the strumming of a guitar, composed as if Poledouris was a bard for the barbarian.[154] This draft became the "Riddle of Steel",[155] a composition played with "massive brass, strings, and percussion",[156] which also serves as Conan's personal theme.[149] The music is first played when Conan's father explains the riddle to him. Laurence E. MacDonald, Professor of Music at Mott Community College, said the theme stirs up the appropriate emotions when it is repeated during Conan's vow to avenge his parents.[149] The film's main musical theme, the "Anvil of Crom",[156] which opens the film with "the brassy sound of twenty-four French horns in a dramatic intonation of the melody, while pounding drums add an incessantly driven rhythmic propulsion" is played again in several later scenes.[149]

Poledouris completed the music that accompanies the attack on Conan's village at the beginning of the film in October 1981.[157] Milius initially wanted a chorus based on Carl Orff's Carmina Burana to herald the appearance of Doom and his warriors in this sequence. After learning that Excalibur (1981) had used Orff's work, he changed his mind and asked his composer for an original creation. Poledouris's theme for Doom consists of "energetic choral passages",[156] chanted by the villain's followers to salute their leader and their actions in his name. The lyrics were composed in English and roughly translated into Latin;[158] Poledouris was "more concerned about the way the Latin words sounded than with the sense they actually made."[159] He set these words to a melody adapted from the 13th-century Gregorian hymn, Dies Irae,[160] which was chosen to "communicate the tragic aspects of the cruelty wrought by Thulsa Doom."[156]

The film's music mostly conveys a sense of power, energy, and brutality, yet there are tender moments.[161] The sounds of oboes and string instruments accompany Conan and Valeria's intimate scenes, imbuing them with a sense of lush romance and an emotional intensity. According to MacDonald, Poledouris deviated from the practice of scoring love scenes with tunes reminiscent of Romantic period pieces; instead, Poledouris made Conan and Valeria's melancholic love theme unique through his use of "minor-key harmony".[158] David Morgan, a film journalist, heard Eastern influences in the "lilting romantic melodies".[161] Page Cook, audio critic for Films in Review, describes Conan the Barbarian's score as "a large canvas daubed with a colorful yet highly sensitive brush. There is innate intelligence behind Poledouris's scheme, and the pinnacles reached are often eloquent with haunting intensity."[148]

From late November 1981, Poledouris spent three weeks recording his score in Rome.[77][162] He engaged a 90-instrument orchestra and a 24-member choir from Santa Cecilia,[163] and conducted them personally.[162] The pieces of music were orchestrated by Greg McRitchie, Poledouris's frequent collaborator.[148] The chorus and orchestra were recorded separately.[164] The 24 tracks of sound effects, music, and dialog were downmixed into a single-channel,[165] making Conan the Barbarian the last film released by a major studio with a mono soundtrack.[166] According to Poledouris, Raffaella De Laurentiis balked at the cost ($30,000) of a stereo soundtrack and was worried over the paucity of theaters equipped with stereo sound systems.[167]

Themes

Riddle of SteelThe secret of steel has always carried with it a mystery. You must learn its riddle, little Conan. You must learn its discipline. For no one, no one in this world can you trust. Not men, not women, not beasts. [Points to sword] This you can trust.

Conan's fatherThe central theme in the film is the Riddle of Steel. At the start of the film, Conan's father tells his son to learn the secret of steel and to trust only it. Initially believing in the power of steel, Thulsa Doom raids Conan's village to steal the Master's sword. Subsequently, the story centers on Conan's quest to recover the weapon in which his father has told him to trust.[168] Weaponry fetish is a device long established in literature; Carl James Grindley, an assistant professor of English, said ancient works such as Homer's Iliad, the Old English poem Beowulf, and the 14th-century tale of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight pay detailed attention to the arsenal of their heroes.[169] Grindley further said that Conan the Barbarian, like most other contemporary action films, uses weapons as convenient plot devices rather than as symbols that mark the qualities of the hero.[170] James Whitlark, an associate professor of English, said the Riddle of Steel makes the film's emphasis on the swords ironic; it gives the allusion that the weapons have powers of their own, but later reveals them to be useless and dependent on the strength of their wielders.[171] In the later part of the film, Doom mocks steel, proclaiming the power of flesh to be stronger. When Conan recovers his father's sword, it is after he has broken it in the hands of Doom's lieutenant during their duel. According to Grindley, that moment—Conan's breaking of his father's sword—"[fulfills] a snickering spectrum of Oedipal conjecture" and asserts Homer's view that "the sword does not make the hero, but the hero makes the sword."[172] The film, as Whitlark says, "offers a fantasy of human power raised beyond mortal limits."[171] Passman agrees, stating the film suggests that the human mind and emotions are stronger than physical might.[7]

Another established literary trope found in the plot of Conan the Barbarian is the concept of death, followed by a journey into the underworld, and rebirth. Donald E. Palumbo, the Language and Humanities Chair at Lorain County Community College, noted that like most other sword and sorcery films, Conan used the motif of underground journeys to reinforce the themes of death and rebirth.[173] According to him, the first scene to involve all three is after Conan's liberation: his flight from wild dogs sends him tumbling into a tomb where he finds a sword that lets him cut off his chains and stand with new found power. In the later parts of the film, Conan experiences two underground journeys where death abounds: in the bowels of the Tower of Serpents where he has to fight a giant snake and in the depths of the Temple of Set where the cultists feast on human flesh while Doom transforms himself into a large serpent. Whereas Valeria dies and comes back from the dead (albeit briefly), Conan's ordeal from his crucifixion was symbolic. Although the barbarian's crucifixion might evoke Christian imagery,[174] associations of the film with the religion are roundly rejected. Milius stated his film is full of pagan ideas, a sentiment supported by film critics such as Elley[94] and Jack Kroll.[35] George Aichele, Professor Emeritus of Philosophy and Religion at Adrian College, suggested the filmmaker's intent with the crucifixion scene was pure marketing: to tease the audience with religious connotations.[175] He, however, suggested that Conan's story can be viewed as an analogy of Christ's life and vice versa.[176] Nigel Andrews, a film critic, saw any connections to Christianity related more to the making of the film.[177]

Milius's concept of Conan the Barbarian as an opera was picked up by the critics; Elley and Huckvale saw connections to Wagner's operas.[94][117] According to Huckvale, the film's opening sequence closely mirrors a sword forging scene in Siegfried. Conan's adventures and ordeals seem to be inspired by the trials of the opera's titular hero: witnessing his parents' deaths, growing up as a slave, and slaying a giant serpent—dragon. Furthermore, Schwarzenegger's appearance in the role of Conan evoked images of Siegfried, the role model of the "Aryan blonde beast", in the lecturer's mind.[117] The notion of racial superiority, symbolized by this Aryan hero, was a criticism given by J. Hoberman and James Wolcott; they highlighted the film's Nietzschean epigraph and labeled its protagonist as Nietzsche's übermensch.[178][179] Ebert was disturbed by the depiction of a "Nordic superman confronting a black", in which the "muscular blond" slices off the black man's head and "contemptuously [throws it] down the flight of stairs".[33] His sentiment was shared by Adam Roberts, an Arthurian scholar, who also said Conan was an exemplar of the sword and sorcery films of the early 1980s that were permeated in various degrees with fascist ideology. According to Roberts, the films were following the ideas and aesthetics laid down in Leni Riefenstahl's directorial efforts for Nazi Germany. Roberts cautioned that any political readings into these sword and sorcery films with regards to fascism is subjective.[180] Film critic Richard Dyer said that such associations with Conan were inaccurate and influenced by misconceptions of Nietzschean philosophies,[181] and scholars of philosophy said that the film industry has often misinterpreted the ideas behind the übermensch.[182][183]

Conan is also seen as a product of its time: the themes of the film reflect the political climate of the United States in the 1980s. Ronald Reagan was the country's president and the ideals of individualism were promoted during his two terms in office. He stressed on the moral worth of the individual in his speeches, encouraging his fellow Americans to make the country successful and to stand up against the Soviet Union during the Cold War.[184][185] Dr. Dave Saunders, a film writer and lecturer at South Essex College of Further and Higher Education, linked facets of Conan the Barbarian to aspects of Reaganism[186]—the conservative ideology that surrounded the president's policies.[187] Saunders likened Conan's quest against Doom to the Americans' crusades,[186] his choice of weaponry—swords—to Reagan's and Milius's fondness of resisting the Soviets with only spirit and simple weapons,[188] and Doom's base of operations to the Kremlin.[189] Conan, in Saunder's interpretation, is portrayed as the American hero who draws strength from his trials and tribulations to slay the evil oppressors—the Soviets—and crush their un-American ways.[190] Kellner and his fellow academic Michael Ryan proposed another enemy for the American individual: an overly domineering federal government.[191] The film's association with individualism was not confined to the United States; Jeffrey Richards, a cultural historian, noticed the film's popularity among the youths of the United Kingdom.[192] Robin Wood, a film critic, suggests that in most cases, there is only a thin veneer between individualism and fascism; he also said that Conan is the only film in that era to dispense with the disguise, openly celebrating its fascist ideals in a manner that would delight Riefenstahl.[193]

Conan shows a world where there are two kinds of men—one of which has long hair and gorgeous tits.[194]

F. X. Feeney, "Conan: Primordial Postcards," L.A. Weekly, May 14–20, 1982.[195]Sexual politics were also examined in thematic studies of the film. The feminist movement experienced a backlash during the opening years of the 1980s and action films then were helping to promote the notions of masculinity.[196][197] Women in these films were portrayed as whores, handmaidens, or warriors and clad in flesh-revealing outfits.[187][198] Conan gave its male audience a manly hero that overcame all odds and adversity, delivering them a fantasy that offered escape from the invasion of radical "strong feminist women" in their lives.[199][200] Renato Casaro's promotional artwork for the film's release in the United States presents a sexualized portrayal of the two main characters, Conan and Valeria.[201][202] Scantily clad in costumes cut in the styles of underwear, they wear long boots and sport their hair loose. While Conan strides forth in the picture with his sword held high, Valeria "squats in an impossible pose with her leather body-suit [in the shape of a teddy] forming a dark shape between her thighs".[203] According to Schubart, critics did not accept Valeria as a strong female figure, but viewed her as a "sexual spectacle"; to them, she was the traditional male warrior buddy in a sexy female body.[194]

Release

In 1980, the producers began advertising to publicize the film. Teaser posters were put up in theaters across the United States. The posters reused Frazetta's artwork that was commissioned for the cover of Conan the Adventurer (1966).[204][205] Laurentiis wanted Conan the Barbarian to start playing in cinemas at Christmas, 1981,[206] but Universal executives requested further editing after they previewed a preliminary version of the film in August. A Hollywood insider said the executives were concerned about the film's portrayal of violence. The premiere was delayed until the following year so changes could be made.[207] Many scenes were excised from Thulsa Doom's attack on Conan's village, including the close-up shots on the decapitated head of Conan's mother;[77] the late notice of the changes forced Poledouris to quickly adjust his score before recording music for the sequence.[157] Other scenes of violence that were cut included Subotai's slaying of a monster at the top of the Tower of Serpents and Conan chopping off a pickpocket's arm in a bazaar.[208] Milius intended to show a 140-minute story; the final release ran 129 minutes.[4] According to Cobb, the total production expenses approached $20 million by the time the film was released.[97]

The United States' public were offered a sneak preview on February 19, 1982, in Houston, Texas. In the following month, previews were held in 30 cities across the country. In Washington D.C., the mass of moviegoers formed long lines that spanned streets, causing traffic jams. Tickets were quickly sold out in Denver, and 1,000 people had to be turned away in Houston. The majority of those in the lines were male; a moviegoer in Los Angeles said, "The audience was mostly white, clean-cut and high-school or college age. It was not the punk or heavy-leather crowd, but an awful lot of them had bulging muscles."[209] On March 16, Conan the Barbarian had its worldwide premiere at Fotogramas de Plata, an annual cinema awards ceremony in Madrid,[210] and began its general release in Spain and France a month later.[211][212] Twentieth Century Fox handled the foreign distribution of the film.[213] Universal originally scheduled Conan's official release in the United States for the weekend before Memorial Day[214]—the start of the film industry's summer season when schools close for a month-long holiday.[215] To avoid competition with other big-budget, high-profile films, the studio advanced the release of Conan the Barbarian and on May 14, 1982, the film officially opened in 1,400 theaters across North America.[214]

Reception

Critical response

The media's reactions toward Conan were polarized. Aspects of the film heavily criticized by one side were regarded in a positive light by the other; Professor Gunden pointed out that "for every positive review the film garnered, it received two negative ones."[216] The opinions of Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times and Richard Schickel of Time magazine illustrate their colleagues' divided views. Ebert called Conan the Barbarian "a perfect fantasy for the alienated preadolescent"[33] whereas Schickel said, "Conan is a sort of psychopathic Star Wars, stupid and stupefying."[217]

At the time Conan was released, the media were inclined to condemn Hollywood's portrayals of violence; typical action films showed the hero attaining his goals by killing all who stood in his way.[4][218] Conan was particularly condemned for its violent scenes,[213][218] which Newsweek's Jack Kroll called "cheerless and styleless".[35] In one of his articles for the San Francisco Chronicle, Stu Schreiberg counted 50 people killed in various scenes.[219] Other film critics differed over the film's portrayal of violence. David Denby wrote in his review for New York magazine that the action scenes were one of the film's few positive features; however, exciting as the scenes were, those such as the decapitation of Conan's mother seemed inane.[2] On the other hand, Vincent Canby, Carlos Clarens, and Pascal Mérigeau were unanimous in their opinion that the film's depicted violence failed to meet their expectations: the film's pacing and Howard's stories suggested more gory material.[212][220][221] According to Paul Sammon, Milius's cuts to assuage concerns over the violence made the scenes "cartoon-like".[4]

Comparison with the source material also produced varying reactions among the critics. Danny Peary and Schickel expected a film based on pulp stories and comic books to be light-hearted or corny, and Milius's introduction of Nietzschean themes and ideology did not sit well with them.[22][217] Others were not impressed with Milius's handling of his ideas; James Wolcott called it heavy-handed and Kroll said the material lacked substance in its implementation.[35][179] The themes of individualism and paganism, however, resonated with many in the audience; the concept of a warrior who relies only on his own prowess and will to conquer the obstacles in his way found favor with young males.[222] Wolcott wrote in Texas Monthly that these themes appeal to "98-pound weaklings who want to kick sand into bullies' faces and win the panting adoration of a well-oiled beach bunny".[179] Kroll's opinion was that the audience loved the violence and carnage but were cynical about the "philosophical bombast."[35] While popular with audiences, the theatrical treatment of the barbarian was rejected by hardcore fans and scholars of Howard's stories. A particular point of contention was the film's version of Conan's origin, which is at odds with Howard's hints about the character's youth.[223] Their point of view is supported by Kerry Brougher,[224] but Derek Elley, Clarens, and Sammon said Milius was faithful to the ideology behind Howard's work.[94][116][225]

Arnold Schwarzenegger's performance was frequently mentioned in the critiques.[213] Clarens, Peary, Gunden and Nigel Andrews were among those who gave positive assessments of the former bodybuilder's acting: to them, he was physically convincing as the barbarian in his body movements and appearance.[22][221][226][227] Andrews added that Schwarzenegger exuded a certain charm—with his accent mangling his dialog—that made the film appealing to his fans.[228] Fanfare's Royal S. Brown disagreed and was grateful that the actor's dialog amounted to "2 pages of typescript."[229] Schickel summed up Schwarzenegger's acting as "flat",[217] while Knoll was more verbose, characterizing the actor's portrayal as "a dull clod with a sharp sword, a human collage of pectorals and latissimi who's got less style and wit than Lassie."[35] While Sandahl Bergman earned acclaim for injecting grace and dynamism into the film,[35][221] the film's more experienced thespians were not spared criticisms. Gunden said von Sydow showed little dedication to his role,[68] and Clarens judged Jones's portrayal of Thulsa Doom to be worse than camp.[221] Brougher faulted none of the actors for their performances, laying the blame on Milius's script instead.[224]

Box office and other media

According to Rentrak Theatrical, a firm of media analysts, Conan debuted at the top spot at the US box office, taking $9,479,373 over the opening weekend.[230][nb 5] Rentrak's data on Conan covered 8 weeks after the film's release; during that period, Conan grossed $38,513,085 at the box office in the United States.[232] Universal Pictures received $22.5 million after deducting the amounts due to the cinema owners.[1] This sum—the rental[233]—was more than the money Universal had invested in making the film, thus qualifying Conan as a commercial success; any further income from the film was pure profit for the studio.[1] Marian Christy, interviewer for the Boston Globe, mentioned that the film was a box office success in Europe and Japan as well.[234] Worldwide, Conan the Barbarian grossed more than $100 million in ticket sales.[235]

David A. Cook, Professor of Film Studies at Emory University, wrote that Conan's North American performance fell short of the amount returned by blockbusters;[236] the rentals of such films from their release in the continent were supposed to be least $50 million.[237] Conan's rental was the thirteenth highest for 1982[1] and when combined with those for E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (the most successful film in that year with a rental of $187 million),[233] On Golden Pond, and The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas—all distributed by Universal Pictures—constituted 30 percent of the year's total film rental. According to Arthur D. Murphy, a film-industry analyst, it was the first time that a single distributor captured such a substantial share of the film market.[237]

The videocassette version of the film was released on October 2, 1982. Sales and rental figures of the videocassette were high; from its launch, the title was listed in Billboard's Videocassette Top 40 (Sales and Rental categories) for 23 weeks.[238][239] According to Sammon, sales of the film through frequent home video releases increased the film's gross earnings to more than $300 million by 2007.[240] Conan the Barbarian was novelized by Lin Carter and the de Camps (L. Sprague and his wife, Catherine).[220][241] It was also adapted by Marvel in comic form;[nb 6] scripted by Michael Fleisher, the comic was one of the rarest paperbacks published by the company.[242]

Accolades

Conan the Barbarian did not receive any film awards, but the Hollywood Foreign Press Association noted Bergman's performance as Valeria and awarded her a Golden Globe Award for New Star of the Year—Actress.[243] Poledouris's score was judged by Films in Review's Page Cook as the second best sound track of the films released in 1982[148] and nominated by the American Film Institute (AFI) for its 100 Years of Film Scores in 2005.[244] The film was one of the nominees for AFI's Top 10 Fantasy Films in 2008 and its protagonist similarly nominated for AFI's 100 Heroes and Villains in 2003.[245][246]

Legacy and impact

Whereas most comic book and pulp adaptations were box office failures in the 1980s, Conan the Barbarian was one of the few that made a profit.[247] According to Sammon, it became the standard against which sword and sorcery films were measured until the debut of Peter Jackson's The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring in 2001;[240] several contemporary films of the same genre were judged by critics to be clones of Conan,[236] such as The Beastmaster (1982).[248][249] Conan's success inspired low-budget copycats, such as Ator, the Fighting Eagle (1982) and Deathstalker (1983).[250][251][252] Its sequel, Conan the Destroyer, was produced and released in 1984; only a few of those involved in the first film, such as Schwarzenegger, Mako, and Poledouris, returned.[156][235] Later big- and small-screen adaptations of Robert E. Howard's stories were considered by Sammon to be inferior to the film that started the trend.[116] A spinoff from Conan was a 20-minute live-action show, The Adventures of Conan: A Sword and Sorcery Spectacular, that ran from 1983 to 1993 at Universal Studios Hollywood. Produced at a cost of $5 million, the show featured action scenes executed to music composed by Poledouris.[163][253] The show's highlights were pyrotechnics, lasers, and an 18 feet (5.5 m) tall animatronic dragon that breathed fire.[254][255]

Several of those involved in the film reaped short-term benefits. Sandahl Bergman's Golden Globe for her role as Valeria marks her greatest achievement in the film industry; her later roles failed to gain her further recognition.[256] Dino De Laurentiis had produced a string of box office failures since the success of King Kong in 1976; it appeared Conan the Barbarian might be a turning point in his fortunes. The sequel was also profitable, but many of Laurentiis' later big-budget projects did not recoup their production costs and he was forced to declare bankruptcy in 1988.[257] For John Milius, Conan the Barbarian is his "biggest directorial success" to date;[258] his subsequent endeavors failed to equal its success and popularity.[259]

Pressman did not receive any money from Conan's box office takings, but he sold the film rights for the Conan franchise to Laurentiis for $4.5 million and 10 percent of the gross of any sequel to Conan the Barbarian.[42] The sale more than paid off his company's debts incurred from producing Old Boyfriends, saving him from financial ruin;[50] Pressman said this deal "made [him] more money by selling out, by not making a movie, than [he] ever have made by making one."[260] He also arranged for Mattel to obtain the rights to produce a range of toys for the film. Although the toy company abandoned the license after its executives decided Conan was "too violent" for children, Pressman convinced them to let him produce a film based on their new Masters of the Universe toy line.[50] The eponymous film cost $20 million to produce and grossed $17 million at the United States box office in 1987.[261][262]

Those who benefited most from the project were Basil Poledouris and Arnold Schwarzenegger. Poledouris's reputation in the film industry increased with the critical acclaim his score received;[263] MacDonald noted Poledouris's work on Conan as "one of the most spectacular film music achievements of the decade",[150] and Page Cook named it as the only reason to watch the film and as the second best film sound track (after E.T.'s) for 1982.[148] After hearing Conan's music, Paul Verhoeven engaged Poledouris to score his films, Flesh and Blood (1985) and RoboCop (1987).[264][265] The music in Verhoeven's Total Recall (1990) also bore the influence of Conan's score; its composer, Jerry Goldsmith, used Poledouris's work as the model for his compositions.[266]

Conan brought Schwarzenegger worldwide recognition as an action star[258] and established the model for most of his film roles: "icy, brawny, and inexpressive—yet somehow endearing."[267] The image of him as the barbarian was an enduring one; when he campaigned for George H. W. Bush to be president, he was introduced as "Conan the Republican"[268]—a moniker that stuck with him throughout his political career and was often repeated by the media during his term as Governor of California.[269] Schwarzenegger was aware of the benefits the film had brought to him, acknowledging the role of Conan as "God's gift to [his] career."[270] He embraced the image: when he was Governor of California, he displayed his copy of the Atlantean sword in his office, occasionally flourishing the weapon at visitors and letting them play with it.[269][271] More than once, he spiced up his speeches with Conan's "crush your enemies, see them driven before you and hear the lamentations of their women".[272][273]

Notes and references

Notes

- ^ The film quotes a paraphrasing by G. Gordon Liddy, former assistant to United States President Richard Nixon. The original line is from Nietzsche's Twilight of the Idols, "From life's school of war: what does not kill me makes me stronger."[3]

- ^ According to Jody Samson, the swordsmith who made the swords used in the film, while the depicted forging is possible in real life, the quenching (cooling the sword after heating it up) by thrusting the weapon into the snow would likely shatter the blade.[5]

- ^ The original English quote, as translated by Sir Henry Hoyle Howorth in 1876 from Abraham Constantin Mouradgea d'Ohsson's French version of Genghis Khan's speech: "The greatest pleasure is to vanquish your enemies, to chase them before you, to rob them of their wealth, to see those dear to them bathed in tears, to ride their horses, to clasp to your bosom their wives and daughters."[75][76]

- ^ The US dollar figure is derived from the exchange rate (82.7500) between the currency and the peseta on January 31, 1981.[104]

- ^ The average price for a movie ticket in 1982 was $2.94.[231]

- ^ Further details of the comic: Fleisher, Michael (Summer 1982). "Conan the Barbarian". Marvel Super Special (New York, United States: Marvel Comics Group) 1 (21). ISBN 0-939766-07-8.

References

- ^ a b c d e f g Gunden 1989, p. 14.

- ^ a b c d Denby 1982, p. 68.

- ^ Whitaker 2003.

- ^ a b c d Sammon 1982b.

- ^ a b c Waterman & Samson 2002.

- ^ Gunden 1989, p. 16.

- ^ a b c Passman 1991, p. 92.

- ^ Gunden 1989, pp. 14, 20.

- ^ Gunden 1989, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Flynn 1996, p. 40.

- ^ a b c d e Sammon 1982a, p. 47.

- ^ Gunden 1989, p. 17.

- ^ a b Gunden 1989, pp. 17–18.

- ^ a b c d e Sammon 1982a, p. 50.

- ^ a b Sammon 1982a, p. 55.

- ^ Gunden 1989, pp. 18–19.

- ^ a b Gunden 1989, p. 19.

- ^ a b Saunders 2009, p. 58.

- ^ a b Gunden 1989, p. 28.

- ^ Helman 2003, p. 276.

- ^ a b c Williams 2010, p. 116.

- ^ a b c Peary 1986.

- ^ Herron 2000, p. 177.

- ^ Herron 2000, pp. 125, 173.

- ^ a b c d Sammon 1982a, p. 37.

- ^ Passman 1991, pp. 90, 93.

- ^ Schubart 2007, p. 36.

- ^ Schubart 2007, p. 232.

- ^ a b Passman 1991, pp. 91–93.

- ^ Passman 1991, p. 104.

- ^ a b Sammon 2007, p. 105.

- ^ Sammon 1981, p. 33.

- ^ a b c d Ebert 1982.

- ^ Gunden 1989, pp. 17–19.

- ^ a b c d e f g Kroll 1982.

- ^ Gallagher & Milius 1989, pp. 177–178.

- ^ a b c d Sammon 1982a, p. 31.

- ^ Ashley 2007, p. 138.

- ^ Turan 1980, pp. 60–61.

- ^ Sammon 2007, pp. 98–100.

- ^ Sammon 2007, pp. 100–101.

- ^ a b c d e Carney 1987, p. 72.

- ^ Hunter 2007, p. 156.

- ^ a b Turan 1980, p. 62.

- ^ a b c d Sammon 1981, p. 25.

- ^ a b c Sammon 1982a, p. 32.

- ^ a b Sammon 1982a, p. 30.

- ^ Sammon & Cobb 1982, p. 65.

- ^ a b c Sammon 1981, p. 26.

- ^ a b c Carney 1987, p. 74.

- ^ Riordan 1994, p. 99.

- ^ McGilligan & Stone 2001, p. 18.

- ^ Gunden 1989, p. 20.

- ^ a b Beaver 1994, p. 50.

- ^ a b Gunden 1989, p. 21.

- ^ Nicholls 1984, pp. 86–88.

- ^ a b c Bruzenak 1981, p. 53.

- ^ Sammon 2007, p. 103.

- ^ Flynn 1996, p. 45.

- ^ Sammon 2007, p. 100.

- ^ Sammon 2007, p. 101.

- ^ Turan 1980, p. 63.

- ^ Andrews 1995, p. 101.

- ^ Gallagher & Milius 1989, p. 26.

- ^ Turan 1980, pp. 63, 66.

- ^ Gunden 1989, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Western Empire 1980.

- ^ a b c Gunden 1989, p. 24.

- ^ Steranko & Bergman 1982, p. 41.

- ^ a b Sammon & Milius 1982, p. 26.

- ^ a b c d Gallagher & Milius 1989, p. 178.

- ^ Steranko & Milius 1982.

- ^ a b Andrews 1995, p. 107.

- ^ a b c Gunden 1989, p. 26.

- ^ Irwin 2007, p. 19.

- ^ Howorth 1876, p. 110.

- ^ a b c d Sammon 1982a, p. 62.

- ^ Turan 1980, p. 66.

- ^ Bebenek 2004.

- ^ Marklund 2010, p. 309.

- ^ Sammon 1981, p. 20.

- ^ Sammon 1981, p. 19.

- ^ Kurohashi 1999, pp. 27, 118.

- ^ a b c d Sammon 1982a, p. 42.

- ^ Williams 2010, p. 115.

- ^ Riordan 1994, p. 126.

- ^ Riordan 1994, p. 102.

- ^ Steranko & Schwarzenegger 1982, p. 26.

- ^ Williams 2010, pp. 115–116.

- ^ Beaver 1994, p. 51.

- ^ McGilligan & Stone 2001, p. 19.

- ^ Riordan 1994, p. 101.

- ^ Gunden 1989, p. 22.

- ^ a b c d e Elley 1984, p. 151.

- ^ Sammon 1982a, p. 29.

- ^ Sammon 1982a, p. 40.

- ^ a b Mitchell, Ferguson & Cobb 1982, p. 20.

- ^ a b c d Sammon 1982a, p. 38.

- ^ Sammon 1981, p. 32.

- ^ Galindo 1981.

- ^ a b c d e Sammon 1982a, p. 56.

- ^ Sammon & Cobb 1982, p. 67.

- ^ Sammon 1981, p. 22.

- ^ Federal Reserve 1989.

- ^ Sammon 1981, p. 34.

- ^ Capella-Miternique 2002, pp. 272, 273, 277–280.

- ^ Sammon 1982a, p. 51.

- ^ Sammon 1982a, p. 71.

- ^ Moya 1999, pp. 212, 218.

- ^ Sammon 1982a, pp. 53–54.

- ^ Sammon 1982a, p. 69.

- ^ Sammon & Cobb 1982, pp. 70–71.

- ^ Sammon 1982a, pp. 47–48.

- ^ Sammon 1981, p. 31.

- ^ Sammon 2007, p. 104.

- ^ a b c Sammon 2007, p. 108.

- ^ a b c Huckvale 1994, p. 133.

- ^ Sammon 1981, p. 37.

- ^ Sammon 1982a, p. 54.

- ^ Sammon 1982a, p. 59.

- ^ Sammon 1981, pp. 37–38.

- ^ Franck 1985, p. 20.

- ^ Franck 1985, pp. 20, 22, 24, 90.

- ^ Franck 1985, p. 24.

- ^ a b c d e Sammon 1982a, p. 35.

- ^ Sammon 1982a, pp. 35, 39.

- ^ Sammon 1982a, p. 39.

- ^ Steranko & Schwarzenegger 1982, p. 31.

- ^ Sammon 1982a, pp. 35–36.

- ^ Sammon 1982a, pp. 56, 60.

- ^ a b Sammon 1981, p. 23.

- ^ a b Sammon 1982a, p. 60.

- ^ Steranko & Schwarzenegger 1982, p. 32.

- ^ Robb 1994, p. 6.

- ^ Sammon 1981, pp. 24, 31.

- ^ Sammon 1981, p. 24.

- ^ Sammon 1982a, pp. 42, 45.

- ^ Sammon 1982a, p. 46.

- ^ Sammon 1982a, pp. 51, 55.

- ^ Sammon 1982a, pp. 57, 59.

- ^ Sammon 1981, p. 36.

- ^ a b Sammon 1982a, pp. 55, 63.

- ^ MacDonald 1998, pp. 291–292.

- ^ Thomas 1997, pp. 324–325.

- ^ Thomas 1997, p. 328.

- ^ ASC 1982.

- ^ ASC 1982, p. 783.

- ^ a b c d e Cook 1983, p. 120.

- ^ a b c d MacDonald 1998, p. 292.

- ^ a b c MacDonald 1998, p. 294.

- ^ ASC 1982, p. 785.

- ^ Morgan 2000, pp. 171–172.

- ^ MacDonald 1998, pp. 292–293.

- ^ Morgan 2000, p. 171.

- ^ Larson 2006.

- ^ a b c d e Thomas 1997, p. 326.

- ^ a b ASC 1982, p. 786.

- ^ a b MacDonald 1998, p. 293.

- ^ Morgan 2000, pp. 170–171.

- ^ Larson 1985, p. 349.

- ^ a b Morgan 2000, p. 167.

- ^ a b Morgan 2000, p. 228.

- ^ a b Koppl & Poledouris 2009.

- ^ Morgan 2000, p. 175.

- ^ Morgan 2000, pp. 172–173.

- ^ Morgan 2000, pp. 167–168.

- ^ Morgan 2000, pp. 173–174.

- ^ Grindley 2004, p. 159.

- ^ Grindley 2004, pp. 151–155.

- ^ Grindley 2004, pp. 155, 159.

- ^ a b Whitlark 1988, p. 115.

- ^ Grindley 2004, p. 160.

- ^ Palumbo 1987, p. 212.

- ^ Palumbo 1987, pp. 213–214.

- ^ Aichele 2002, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Aichele 2002, p. 8.

- ^ Andrews 1995, p. 104.

- ^ Hoberman 2000, p. 30.

- ^ a b c Wolcott 1982, p. 160.

- ^ Roberts 1998, pp. 110–111.

- ^ Dyer 2002, p. 265.

- ^ Jovanovski 2008, p. 105.

- ^ Solomon 2003, p. 33.

- ^ Shaw 2007, pp. 267–269.

- ^ Saunders 2009, pp. 48–49.

- ^ a b Saunders 2009, p. 51.

- ^ a b Kellner 2004, p. 73.

- ^ Saunders 2009, pp. 51–52.

- ^ Saunders 2009, p. 57.

- ^ Saunders 2009, pp. 53–58.

- ^ Ryan & Kellner 1990, p. 226.

- ^ Richards 1997, pp. 23, 170.

- ^ Wood 2003, p. 152.

- ^ a b Schubart 2007, p. 18.

- ^ Schubart 2007, p. 326.

- ^ Cross 2008, p. 191.

- ^ Thompson 2007, pp. 103–104.

- ^ Passman 1991, p. 91.

- ^ Cross 2008, pp. 155–156.

- ^ Wood 2003, p. xxxvi.

- ^ Sammon 2007, pp. 96–97.

- ^ Schubart 2007, p. 224.

- ^ Schubart 2007, pp. 224–225.

- ^ Heritage Auctions 2010, p. 118.

- ^ Sammon 2007, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Segaloff 1981.

- ^ Churcher 1981, p. 12.

- ^ Gunden 1989, p. 27.

- ^ Harmetz 1982.

- ^ ABC 1982b.

- ^ ABC 1982a.

- ^ a b Mérigeau 1982.

- ^ a b c Flynn 1996, p. 48.

- ^ a b BusinessWeek 1982.

- ^ Kilday 1999, pp. 40, 42.

- ^ Gunden 1989, p. 15.

- ^ a b c Schickel 1982.

- ^ a b Andrews 1995, pp. 108–109.

- ^ Andrews 1995, p. 141.

- ^ a b Canby 1982a.

- ^ a b c d Clarens 1982, p. 28.

- ^ Richards 1997, p. 170.

- ^ Sammon 2007, pp. 103–104, 108.

- ^ a b Brougher 1982, p. 103.

- ^ Clarens 1982, p. 27.

- ^ Gunden 1989, pp. 15–16, 26.

- ^ Andrews 1995, pp. 100, 105–106.

- ^ Andrews 1995, p. 106.

- ^ Brown 1982, p. 486.

- ^ Rentrak Corporation 2011a.

- ^ Vogel 2011, p. 91.

- ^ Rentrak Corporation 2011b.

- ^ a b Prince 2000, p. 3.

- ^ Christy 1982.

- ^ a b Sammon 1984, p. 5.

- ^ a b Cook 1999, p. 32.

- ^ a b Harmetz 1983.

- ^ Billboard 1982.

- ^ Billboard 1983.

- ^ a b Sammon 2007, p. 107.

- ^ Canby 1982b.

- ^ Weiner 2008, p. 216.

- ^ HFPA 2011.

- ^ AFI 2005, p. 3.

- ^ AFI 2008, p. 18.

- ^ AFI 2003, p. 12.

- ^ Rossen 2008, p. 127.

- ^ Gunden 1989, p. 247.

- ^ Maltin 2008, p. 97.

- ^ McDonagh 2008, p. 135.

- ^ Andrews 2006, p. 101.

- ^ Falicov 2003, p. 26.

- ^ Sammon 2007, pp. 114, 117.

- ^ Universal Studios 1983.

- ^ Moleski 1985.

- ^ Flynn 1996, pp. 79–80.

- ^ Behar 1990.

- ^ a b Kendrick 2009, p. 87.

- ^ Cook 1999, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Pulleine 1986.

- ^ Twitchell 1992, p. 248.

- ^ Rossen 2008, p. 169.

- ^ Thomas 1997, p. 325.

- ^ Larson & Poledouris 2008.

- ^ Morgan 2000, p. 55.

- ^ Karlin 1994, p. 6.

- ^ Rees 1992, p. 1992.

- ^ Popadiuk 2009, p. 96.

- ^ a b Grover & Palmeri 2004.

- ^ Geringer 1987, pp. 89–90.

- ^ Brenner 2005, p. 3.

- ^ LeDuff & Broder 2004, p. 1.

- ^ Fox 2011.

Bibliography

- Books

- Aichele, George (2002). "Foreword". In Kreitzer, Larry Joseph. Gospel Images in Fiction and Film: On Reversing the Hermeneutical Flow. Biblical Seminar. 84. Sheffield, United Kingdom: Sheffield Academic Press. pp. 7–10. ISBN 1-841-27343-0.

- Andrews, David (2006). "Spicy, but Not Obscene". Soft in the Middle: The Contemporary Softcore Feature in its Contexts. Ohio, United States: Ohio State University Press. pp. 77–109. ISBN 0-8142-1022-8.

- Andrews, Nigel (1995). True Myths: The Life and Times of Arnold Schwarzenegger. London, United Kingdom: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 0-7475-2126-3.

- Ashley, Michael (2007). "The Depths of Infinity". Gateways to Forever: The Story of the Science-Fiction Magazines from 1970 to 1980. Liverpool, United Kingdom: Liverpool University Press. pp. 135–139. ISBN 978-1-84631-002-7. http://books.google.com/books?id=2qkmF8HvP_gC&pg=PA135.

- Beaver, Frank (1994). "Writing for the Establishment: Conan the Barbarian, Scarface, Year of the Dragon, 8 Million Ways to Die". Oliver Stone: Wakeup Cinema. Twayne's Filmmakers Series. New York, United States: Twayne Publishers. pp. 48–66. ISBN 0-8057-9332-1.

- Bebenek, Chris (2004). "Jones, James Earl". In Gates, Henry Louis; Higginbotham, Evelyn Brooks. African American Lives. New York, United States: Oxford University Press. pp. 473–474. ISBN 0-19-516024-X. http://books.google.com/books?id=3dXw6gR2GgkC&pg=PA473.

- Cross, Gary (2008). Men to Boys: The Making of Modern Immaturity. New York, United States: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-14430-8.

- Dyer, Richard (2002). "The White Man's Muscles". In Adams, Rachel; Savran, David. The Masculinity Studies Reader. Oxford, United Kingdom: Blackwell Publishers. pp. 262–273. ISBN 0-631-22660-5. This was originally printed in White. London, United Kingdom: Routledge. 1997. pp. 145–153, 155–165, 230–231. ISBN 0-415-09537-9.

- Elley, Derek (1984). "Early Medieval: Norsemen, Saxons, and the Cid". The Epic Film: Myth and History. Cinema and Society. London, United Kingdom: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 136–159. ISBN 0-7100-9656-9.

- Flynn, John L. (1996) [1993]. The Films of Arnold Schwarzenegger. Citadel Press Book (Revised and updated ed.). New York, United States: Carol Publishing Group. ISBN 0-8065-1645-3.