- Alamo Mission in San Antonio

-

The Alamo

The chapel of the Alamo Mission is known as the "Shrine of Texas Liberty"[2]

The chapel of the Alamo Mission is known as the "Shrine of Texas Liberty"[2]Location: San Antonio, Texas Coordinates: 29°25′33″N 98°29′10″W / 29.42583°N 98.48611°WCoordinates: 29°25′33″N 98°29′10″W / 29.42583°N 98.48611°W Built: 1744 Governing body: Daughters of the Republic of Texas Part of: Alamo Plaza Historic District (#77001425) NRHP Reference#: 66000808[1] Significant dates Added to NRHP: October 15, 1966 Designated NHL: December 19, 1960[3] Designated CP: July 13, 1977[4] The Alamo, originally known as Mission San Antonio de Valero, is a former Roman Catholic mission and fortress compound, site of the Battle of the Alamo in 1836, and now a museum, in San Antonio, Texas.

The compound, which originally comprised a sanctuary and surrounding buildings, was built by the Spanish Empire in the 18th century for the education of local Native Americans after their conversion to Christianity. In 1793, the mission was secularized and soon abandoned. Ten years later, it became a fortress housing the Mexican Army group the Second Flying Company of San Carlos de Parras, who likely gave the mission the name "Alamo."

Mexican soldiers held the mission until December 1835, when General Martin Perfecto de Cos surrendered it to the Texian Army following the siege of Bexar. A relatively small number of Texian soldiers then occupied the compound. Texian General Sam Houston believed the Texians did not have the manpower to hold the fort and ordered Colonel James Bowie to destroy it. Bowie chose to disregard those orders and instead worked with Colonel James C. Neill to fortify the mission. On February 23, Mexican General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna led a large force of Mexican soldiers into San Antonio de Bexar and promptly initiated a siege. The siege ended on March 6, when the Mexican army attacked the Alamo; by the end of the Battle of the Alamo all or almost all of the defenders were killed. When the Mexican army retreated from Texas at the end of the Texas Revolution, they tore down many of the Alamo walls and burned some of the buildings.

For the next five years, the Alamo was periodically used to garrison soldiers, both Texian and Mexican, but was ultimately abandoned. In 1849, several years after Texas was annexed to the United States, the US Army began renting the facility for use as a quartermaster's depot. The US Army abandoned the mission in 1876 after nearby Fort Sam Houston was established. The Alamo chapel was sold to the state of Texas, which conducted occasional tours but made no effort to restore it. The remaining buildings were sold to a mercantile company which operated them as a wholesale grocery store.

After forming in 1892, the Daughters of the Republic of Texas (DRT) began trying to preserve the Alamo. In 1905, Adina Emilia de Zavala and Clara Driscoll successfully convinced the legislature to purchase the buildings and to name the DRT permanent custodians of the site. For the next six years, de Zavala and Driscoll quarrelled over how to best restore the mission, culminating in a court case to decide which of their competing DRT chapters controlled the Alamo. As a result of the feud, Texas governor Oscar B. Colquitt briefly took the complex under state control and began restorations in 1912; the site was given back to the DRT later that year. The legislature took steps in 1988 and again in 1994 to transfer control of the Alamo to the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department but the attempt failed after then-governor George W. Bush vowed to veto any bill removing the DRT's authority.

Contents

Mission

In 1716, the Spanish government established several Roman Catholic missions in East Texas. The isolation of the missions—the nearest Spanish settlement, San Juan Bautista, Coahuila was over 400 miles (644 km) away—made it difficult to keep them adequately provisioned.[5] To assist the missionaries, the new governor of Spanish Texas, Martín de Alarcón, wished to establish a way station between the settlements along the Rio Grande and the new missions in East Texas.[6] In April 1718, Alarcón led an expedition to found a new community in Texas.[7] On May 1, the group erected a temporary mud, brush, and straw structure near the headwaters of the San Antonio River.[6][7] This building would serve as a new mission, San Antonio de Valero, named after Saint Anthony of Padua and the viceroy of New Spain, Baltasar de Zúñiga y Guzmán Sotomayor y Sarmiento, Marquess of Valero. The mission, headed by Father Antonio de San Buenaventura y Olivares, was located near a community of Coahuiltecans and was initially populated by three to five Indian converts from Mission San Francisco Solano near San Juan Bautista.[7][8] One mile (two km) north of the mission, Alarcón built a presidio (fort), the Presidio San Antonio de Bexar. Close by, he founded the first civilian community in Texas, San Antonio de Bexar (now San Antonio, Texas).[6][7]

Within a year, the mission moved to the western bank of the river, where it was less likely to flood.[8] Over the next several years, a chain of missions were established nearby.[9] In 1724, after remants of a Gulf Coast hurricane destroyed the existing structures at Mission San Antonio de Valero, the mission was moved to its current location.[10] At the time, the new location was just across the San Antonio River from the town of San Antonio de Bexar, and just north of a group of huts known as La Villita.[11]

Over the next several decades, the mission complex expanded to cover 3 acres (1.2 ha).[11] The first permanent building was likely the two-story, L-shaped stone residence for the priests. The building served as parts of the west and south edges of an inner courtyard.[12] A series of adobe barracks buildings were constructed to house the mission Indians and a textile workshop was erected. By 1744, over 300 Indian converts resided at San Antonio de Valero. The mission was largely self-sufficient, relying on its 2000 head of cattle and 1300 sheep for food and clothing. Each year, the mission's farmland produced up to 2000 bushels of corn and 100 bushels of bean; cotton was also grown.[10]

The first stones were laid for a more permanent church building in 1744.[10] The church, its tower and the sacristy fell down in the late 1750s.[13] Construction began again in 1758. The new chapel was located at the south end of the inner courtyard. Constructed of 4 feet (1.2 m) thick limestone blocks, it was intended to be three stories high, topped by a dome, with bell towers on either side.[11] Its shape was a traditional cross, with a long nave and short transept.[13] Although the first two levels were completed, the bell towers and third story were never begun.[11] Four stone arches were erected to support the planned dome, but the dome itself was not built.[14] As the church was never completed, it is unlikely that is was ever used for religious services.[13]

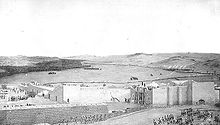

This is one of the first drawings depicting Mission San Antonio de Valero. It was created in 1838 by Mary Maverick and clearly shows statues within the niches.

This is one of the first drawings depicting Mission San Antonio de Valero. It was created in 1838 by Mary Maverick and clearly shows statues within the niches.

The chapel was intended to be highly decorated. Niches were carved on either side of the door to hold statues. The lower-level niches displayed Saint Francis and Saint Dominic, while the second-level niches contained statues of Saint Clare and Saint Margaret of Cortona. Carvings were also completed around the chapel's door.[11]

Up to 30 adobe or mud buildings were constructed to serve as workrooms, storerooms, and homes for the Indian residents. As the nearby presidio was perpetually understaffed, the mission was built to withstand attacks by Apache and Comanche raiders.[12] In 1745, 100 mission Indians successfully drove off a band of 300 Apaches which had surrounded the presidio. Their actions saved the presidio, the mission, and likely the town from destruction.[9] Walls were erected around the Indian homes in 1758, likely in response to a massacre at the San Saba mission.[12] The convent and church were not fully enclosed within the 8 feet (2.4 m) walls. The walls were built 2 feet (0.61 m) thick and enclosed an area 480 feet (150 m) long (north-south) and 160 feet (49 m) wide (east-west). For additional protection, a turret housing three cannon was added near the main gate in 1762. By 1793 an additional one-pounder cannon had been placed on a rampart near the convent.[15]

The population of Indians fluctuated, from a high of 328 in 1756 to a low of 44 in 1777.[12] The new commandant general of the interior provinces, Teodoro de Croix, thought the missions were largely a liability and began taking actions to decrease their influence. In 1778, he ruled that all unbranded cattle belonged to the government. Raiding Apache tribes had stolen most of the mission's horses, making it extremely difficult to round up and brand the cattle. As a result, when the ruling took effect, the mission lost a great deal of its wealth and was unable to support a larger population of converts.[16] By 1793, only 12 Indians remained.[12][Note 1] By this point, few of the hunting and gathering tribes in Texas had not been Christianized. In 1793, Mission San Antonio de Valero was secularized.[17]

The mission was soon abandoned. Most locals were uninterested in the buildings.[18] Visitors were often more impressed. In 1828, French naturalist Jean Louis Berlandier visited the area. He mentioned the Alamo complex: "An enormous battlement and some barracks are found there, as well as the ruins of a church which could pass for one of the loveliest monuments of the area, even if its architecture is overloaded with ornamentation like all the ecclesiastical buildings of the Spanish colonies."[19]

Military

In the 19th century, the mission complex became known as "the Alamo". The name may have been derived from the grove of nearby cottonwood trees, known in Spanish as álamo. Alternatively, the complex may have taken the nickname of a company of Spanish soldiers. In 1803, the abandoned compound was occupied by the Second Flying Company of San Carlos de Parras, from Álamo de Parras in Coahuila. Locals often called them simply the "Alamo Company".[14]

During the Mexican War of Independence, parts of the mission frequently served as a prison for those whose political beliefs did not match the current authority.[20] Between 1806 and 1812 it also served as San Antonio's first hospital. Spanish records indicate that some renovations were made for this purpose, but no details are provided.[18]

The buildings were transferred from Spanish to Mexican control in 1821 after Mexico received its independence. Soldiers continued to garrison in the complex until December 1835, when General Martín Perfecto de Cos surrendered to Texian forces during the Texas Revolution. In the few months that Cos supervised the troops garrisoned in San Antonio, he had ordered many improvements to the Alamo.[21] Cos's men likely demolished the four stone arches that were to support a future chapel dome. The debris from these was used to build a ramp to the apse of the chapel building. There, the Mexican soldiers placed three cannon, which could fire over the walls of the roofless building.[22] To close a gap between the church and the barracks (formerly the convent building) and the south wall, the soldiers built a palisade.[22] When Cos retreated, he left behind 19 cannon, including an 18-pounder.[23]

Battle of the Alamo

Main article: Battle of the AlamoYou can plainly see that the Alamo never was built by a military people for a fortress.

Letter, dated January 18, 1836, from engineer Green B. Jameson to Sam Houston, commander of the Texian forces.[24]With Cos's departure, there was no longer an organized garrison of Mexican troops in Texas,[25] and many Texians believed the war was over.[26] Colonel James C. Neill assumed command of the 100 soldiers who remained. Neill requested that an additional 200 men be sent to fortify the Alamo,[27] and expressed fear that his garrison could be starved out of the Alamo after a four-day siege.[28] However, the Texian government was in turmoil and unable to provide much assistance.[29] Determined to make the best of the situation, Neill and engineer Green B. Jameson began working to fortify the Alamo. Jameson installed the cannons that Cos had left along the walls.[23]

Heeding Neill's warnings, General Sam Houston ordered Colonel James Bowie to take 35–50 men to Bexar to help Neill move all of the artillery and destroy the Alamo.[29] There were not enough oxen to move the artillery someplace safer, and most of the men believed the complex was of strategic importance to protecting the settlements to the east. On January 26 the Texian soldiers passed a resolution in favor of holding the Alamo.[30] On February 11, Neill went on furlough, likely to pursue additional reinforcements and supplies for the garrison. William Travis and Bowie agreed to share command of the Alamo.[31][32]

On February 23 the Mexican army, under the command of General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna, arrived in San Antonio de Bexar.[33] For the next thirteen days, the Mexican Army laid siege to the Alamo. During the siege, work continued on the interior of the Alamo. After Mexican soldiers tried to block the irrigation ditch leading into the Alamo, Jameson supervised the digging of a well at the south end of the plaza. Although the men hit water, they weakened an earth and timber parapet by the low barracks; the mound collapsed, leaving no way to fire safely over that wall.[34]

The siege ended in a fierce battle on March 6. As the Mexican army overran the walls and began gathering in the interior of the Alamo compound, most of the Texians fell back to the long barracks (convent) and the chapel. During the siege, Texians had carved holes in many of the walls of these rooms so that they would be able to fire.[35] Each room had only one door which led into the courtyard[36] and which had been "buttressed by semicircular parapets of dirt secured with cowhides".[37] Some of the rooms even had trenches dug into the floor to provide some cover for the defenders.[38] Mexican soldiers used the abandoned Texian cannon to blow off the doors of the rooms, allowing Mexican soldiers to enter and defeat the Texians.[37]

The last of the Texians to die were the eleven men manning the two 12 lb (5.4 kg) cannon in the chapel.[39][40] The entrance to the church had been barricaded with sandbags, which the Texians were able to fire over. A shot from the 18 lb (8.2 kg) cannon destroyed the barricades, and Mexican soldiers entered the building after firing an initial musket volley. With no time to reload, the Texians, including Dickinson, Gregorio Esparza, and Bonham, grabbed rifles and fired before being bayoneted to death.[41] Texian Robert Evans was master of ordnance and had been tasked with keeping the gunpowder from falling into Mexican hands. Wounded, he crawled towards the powder magazine but was killed by a musket ball with his torch only inches from the powder.[41] If he had succeeded, the blast would have destroyed the church.[42]

Santa Anna ordered that the Texian bodies be stacked and burned.[43][Note 2] All or almost all of the Texian defenders were killed, although some historians believe that at least one Texian, Henry Warnell, successfully escaped from the battle. Warnell died several months later of wounds incurred either during the final battle or during his escape as a courier.[44][45] Most Alamo historians agree that 400–600 Mexicans were killed or wounded.[46][47][48] This would represent about one-third of the Mexican soldiers involved in the final assault, which Todish remarks is "a tremendous casualty rate by any standards".[46]

Further military use

Following the battle of the Alamo, one thousand Mexican soldiers, under General Juan Andrade, remained at the mission. For the next two months they repaired and fortified the complex, so that it could continue to serve as a major Mexican fort within Texas. No records remain of what improvements they made to the structure.[49] After the Mexican army's defeat at the Battle of San Jacinto and the capture of Santa Anna, the Mexican army agreed to leave Texas, effectively ending the Texas Revolution. As Andrade and his garrison joined the retreat on May 24, they spiked the cannons, tore down many of the Alamo walls, and set fires throughout the complex.[50] Only a few buildings survived their efforts—the chapel was left in ruins, most of the Long Barracks was still standing, and the building that had contained the south wall gate and several rooms was mostly intact.[22]

The Texians briefly used the Alamo as a fortress in December 1836 and again in January 1839. The Mexican army regained control in March 1841 and September 1842 as they briefly took San Antonio de Bexar. According to historians Roberts and Olson, "both groups carved names in the Alamo's walls, dug musket rounds out of the holds, and knocked off stone carvings".[50] Pieces of the debris were sold to tourists, and in 1840 the San Antonio town council passed a resolution allowing local citizens to take stone from the Alamo at a cost of $5 per wagonload.[50] By the late 1840s, even the four statues located on the front wall of the chapel had been removed.[51]

On January 13, 1841, the Republic of Texas passed an act returning the sanctuary of the Alamo to the Roman Catholic Church.[52] By 1845, when Texas was annexed to the United States, a colony of bats occupied the abandoned complex and weeds and grass covered many of the walls.[53]

As the Mexican-American War loomed in 1846, 2000 United States Army soldiers were sent to San Antonio under Brigadier General John Wool. By the end of the year, they had appropriated part of the Alamo complex for the Quartermaster's Department. Within eighteen months, the convent building had been restored to serve as offices and storerooms. The chapel remained vacant, however, as the army, the Roman Catholic Church, and the city of San Antonio bickered over its ownership. An 1855 decision by the Texas Supreme Court reaffirmed that the Catholic Church was the rightful owner of the chapel.[52] Even while litigation was ongoing, the army rented the chapel from the Catholic Church for $150 per month.[53]

Under the army's oversight, the Alamo was greatly repaired. Soldiers cleared the grounds and rebuilt the old convent and the mission walls, primarily from original stone which was strewn along the ground. During the renovations, a new wooden roof was added to the chapel and the campanulate, or bell-shaped facade, was added to the front wall of the chapel. At the time, reports suggested that the soldiers found several skeletons while clearing the rubble from the chapel floor. The new chapel roof was destroyed in a fire in 1861.[53] The army also cut additional windows into the chapel, adding two on the upper level of the facade as well as additional windows on the other three sides of the building.[51] The complex eventually contained a supply depot, offices, storage facilities, a blacksmith shop, and stables.[54]

During the American Civil War, Texas joined the Confederacy, and the Alamo complex was taken over by the Confederate Army.[55] In February 1861, the Texan Militia, under direction from the Texas Secession Convention and led by Ben McCullough and Sam Maverick, confronted General Twiggs, commander of all US Forces in Texas and headquartered at the Alamo. Twiggs elected to surrender and all supplies were turned over to the Texans.[56] Following the Confederacy's defeat, the United States Army again maintained control over the Alamo.[54] Shortly after the war ended, however, the Catholic Church requested that the army vacate the premises so that the Alamo could become a place of worship for local German Catholics. The army refused, and the church made no further attempts at retaking the complex.[55]

Mercantile

The army abandoned the Alamo in 1876, when Fort Sam Houston was established in San Antonio. At about that time, the Church sold the convent to Honore Grenet, who added a new two-story wood building to the complex. Grenet used the convent and the new building for a wholesale grocery business.[53] After Grenet's death in 1882, his business was purchased by mercantile firm Hugo & Schmeltzer, which continued to operate the store.[57]

San Antonio's first rail service began in 1877, and the city's tourism industry began to grow. The city heavily advertised the Alamo, using photographs or drawings that showed only the chapel, not the city surrounding it. Many of the visitors were disappointed with their visit; in 1877 tourist Harrier P. Spofford wrote that the chapel was "a reproach to all San Antonio. Its wall is overthrown and removed, its dormitories are piled with military stores, its battle-scarred front has been revamped and repainted and market carts roll to and fro on the spot where flames ascended ... over the funeral pyre of heroes".[58]

Ownership transfer

In 1883, the Catholic Church sold the chapel to the State of Texas for $20,000. The state hired Tom Rife to manage the building. He gave tours but did not make any efforts to restore the chapel, to the annoyance of many. In the past decades, soldiers and members of the local Masonic lodge, which had used the building for meetings, had inscribed various graffiti on the walls and statues. In May 1887 a devout Catholic who was incensed that Masonic emblems had been inscribed on a statue of Saint Theresa was arrested after breaking into the building and smashing statues with a sledgehammer.[57]

The 50th anniversary of the fall of the Alamo received little attention. In an editorial after the fact, the San Antonio Express called for the formation of a new society that would help recognize important historical events. The Daughters of the Republic of Texas (DRT) finally organized in 1892; one of their main goals was to preserve the Alamo.[59] Among its early members was Adina Emilia De Zavala, granddaughter of Republic of Texas Vice-President Lorenzo de Zavala. Shortly before the turn of the century, Adina de Zavala convinced Gustav Schmeltzer, owner of the convent, to give the DRT first option in purchasing the building if it was ever sold. In 1903, Schmeltzer announced that he wanted to sell the convent building to a developer so that it could be turned into a hotel. He offered to sell the building to the DRT for $75,000, which they did not have. De Zavala decided to ask for a donation from the owners of the Menger Hotel, hoping that they would be willing to pay so as not to have competition. On the day of her impromptu visit, however, the owners were away and de Zavala struck up a conversation with a hotel patron, Clara Driscoll. Driscoll was an heiress who was very interested in Texas history and especially the Alamo.[60]

Clara Driscoll in 1903

After their conversation, Driscoll joined the DRT and was almost immediately appointed chair of the San Antonio chapter's fund-raising committee. The DRT was able to negotiate a 30-day option on the property. The group would pay $500 up front, with an additional $4,500 due at the conclusion of the 30 days. On February 10, 1904, the group would owe $20,000, and the remainder of the cost would be paid in five annual installments of $10,000 each. On March 17, 1903, Driscoll paid the initial $500 deposit out of her personal funds. To raise the rest of the money, Driscoll's fund-raising committee sent tens of thousands of letters to Texas residents, asking each person to donate 50 cents. By the end of the 30-day option, the group had collected only $1,021.75 in donations.[61]

On April 17, Driscoll paid the remainder of the $4,500 from her own pocket. At the urging of both Driscoll and de Zavala, the Texas Legislature approved $5,000 for the committee to use as part of the next payment. The appropriation was vetoed by Governor S. W. T. Lanham, who said it was "not a justifiable expenditure of the taxpayers' money".[62] Undeterred, DRT members set up a collection booth outside of the Alamo and held several fundraising activities. Through these activities, they raised $5,662.23. Driscoll again agreed to make up the difference, and also agreed to pay the final $50,000. After hearing of her generosity, various newspapers in Texas dubbed her the "Savior of the Alamo".[62] As news of her donation spread, many groups throughout the state began to petition the legislature to reimburse Driscoll. In January 1905, de Zavala drafted a bill to that effect that was sponsored by representative Samuel Ealy Johnson, Jr. (father of future US President Lyndon Baines Johnson). The bill was passed, and Driscoll received all of her money back. The bill also named the DRT custodian of the Alamo and convent, and they received official control on September 5, 1905.[62]

Soon after the San Antonio chapter of the DRT gained custody of the Alamo, Driscoll and de Zavala began arguing over how best to preserve the building. De Zavala wished to restore the exterior of the buildings to a state similar to its 1836 appearance. As most of the defenders of the battle of the Alamo who died indoors had died in the convent (then called the long barracks), she wished to make that building a focal point of the site. She envisioned a museum and library on the ground floor, and a tribute to the defenders on the second floor. Driscoll, on the other hand, wanted to tear down the long barracks. According to Roberts and Olson, Driscoll wanted to create a monument similar to those she had seen in Europe, "a city center opened by a large plaza and anchored by an ancient chapel".[63]

Unable to convince de Zavala and her supporters to agree to tear down the convent, Driscoll and several other women seceded from the San Antonio chapter of the DRT and formed a competing chapter they named the Alamo Mission chapter. The two chapters promptly began arguing over which had oversight of the Alamo. Unable to quickly resolve the dispute, in February 1908 the executive committee of the DRT decided to lease out the building.[64] Angry with that decision, on February 10 de Zavala held a press conference and announced that a syndicate wanted to buy the chapel and tear it down.[64] She then barricaded herself in the Hugo and Schmetlzer building for three days.[65]

In response to the drama that de Zavala created, on February 12, Governor Thomas Mitchell Campbell ordered that the superintendent of public building and grounds take control of the property. The two DRT chapters took their dispute to the courts, which eventually named Driscoll's chapter the official custodians of the Alamo.[66] The DRT later expelled de Zavala and her followers.[67]

Restoration

Theodore Roosevelt giving a speech at the Alamo, April 7, 1905. The picture shows the building that had been added by Hugo and Schmeltzer.

Theodore Roosevelt giving a speech at the Alamo, April 7, 1905. The picture shows the building that had been added by Hugo and Schmeltzer.

Driscoll offered to donate the money required to tear down the convent, build a stone wall around the Alamo complex, and convert the interior into a park.[67] The legislature was asked to make the final determination of what should be done with the convent. Many members of the legislature saw no good way to end the battle; Robert and Olson commented that "regardless of what they decided, they were going to end up having a group of very angry, very politically active women aligned against them".[68] The legislature thus postponed a decision until after the 1910 elections. Those elections gave the state a new governor, Oscar Branch Colquitt. On December 28, 1911, Colquitt held a meeting for "all persons interested, and who had any information they could give me, about the Alamo as it stood at the time of the butchery of Travis and his men".[68] Both de Zavala and Driscoll spoke, and Colquitt toured the property. Three months after his visit, Colquitt removed the DRT as official custodians of the Alamo, citing the fact that they had done nothing to restore the property since gaining control. He also announced an intent to rebuild the convent. Shortly thereafter, the legislature paid to demolish the building that had been added by Hugo and Schmeltzer and authorized $5000 to restore the rest of the complex. The restorations were begun but could not be finished as the appropriation was not large enough to cover all of the costs.[68]

Driscoll was livid over Colquitt's decisions and used her influence as a major donor to the Democratic Party to undermine him. At the time, Colquitt was considered running for U.S. Senate. Driscoll told the New York Herald Tribune that "the Daughters desire to have a Spanish garden on the site of the old mission, but the governor will not consider it. Therefore, we are going to fight him from the stump. ... We are also going to make speeches in the districts of State Senators who voted against and killed the amendment" to return control of the mission to the DRT.[69] In a compromise and to save face, Colquitt left the state, ostensibly on state business. This left Lieutenant Governor William Harding Mayes in authority. In 1913, Mayes agreed to allow the upper-story walls to be removed from the convent, leaving only the one-story walls of the west and south portions of the building. The conflict over what to do with the buildings became known as the Second Battle of the Alamo.[69]

Over the next several decades, Driscoll continued to work towards creating a plaza with the chapel as its centerpiece. In 1931, she convinced the state legislature to purchase two tracts of land between the chapel and Crockett street. The legislature appropriated most of the money necessary to buy the land, and Driscoll paid the remainder out of her own pocket. The legislature was later convinced to repay her.[70] In 1935, she convinced the city of San Antonio not to place a fire station in a building near the Alamo; the DRT later purchased that building and made it the DRT library.[71]

During the Great Depression, money from the Works Progress Administration and the National Youth Administration was used to construct a wall around the Alamo, to build a museum, and to raze several old buildings that were left on the Alamo property.[72]

As recognition for their efforts in trying to preserve the Alamo, when Driscoll died in July 1945 and de Zavala died in March 1955, their bodies were laid in state in the Alamo Chapel.[73]

The Alamo was designated a National Historic Landmark on December 19, 1960, was documented by the Historic American Buildings Survey in 1961,[74] was added to the National Register of Historic Places when they were founded in 1966, and is a contributing propertly to the Alamo Plaza Historic District, which was designated in 1977. As San Antonio prepared to host the Hemisfair in 1968, the long barracks was roofed and turned into a museum. Few structural changes have taken place since then.[75]

According to Herbert Malloy Mason's Spanish Missions of Texas, the Alamo is one of "the finest examples of Spanish ecclesiastical building on the North American continent".[76][Note 3] The mission, along with the others located in San Antonio, is at risk from environmental factors, however. The limestone used to construct the buildings was taken from the banks of the San Antonio River. It expands when confronted with moisture and then contracts when temperatures drop, shedding small pieces of limestone with each cycle. Measures have been taken to partially combat the problem.[77]

Ownership dispute

In 1988, a theater near the Alamo unveiled a new movie, Alamo ... the Price of Freedom. The 40-minute long film would be screened several times each day. The movie attracted much protest from Mexican American activists, who decried the anti-Mexican comments and complained that it ignored Tejano contributions to the battle. The movie was re-edited in response to the complaints, but the controversy grew to the point that many activists began pressuring the legislature to move control of the Alamo to the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC).[78] In response to pressure from Hispanic groups, state representative Orlando Garcia of San Antonio began legislative hearings into DRT finances. The DRT agreed to make their financial records more open, and the hearings were canceled.[79]

[The Alamo is] one of the most important history structures in the state. It belongs to everyone, or at least it should. ... [It] shouldn't be managed by any private group–I don't care if it is the Daughters of the Republic of Texas, the Elks, the Muslims, or the Water Buffalo Club.

Texas legislator Ron Wilson, who wished to transfer oversight of the Alamo to the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.[80]Shortly after that, San Antonio representative Jerry Beauchamp proposed that the Alamo be transferred from the DRT and to the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. Many minority legislators agreed with him.[80] However, the San Antonio mayor, Henry Cisneros, advocated that control remain with the DRT, and the legislature shelved the bill.[80]

Several years later, Carlos Guerra, a reporter for the San Antonio Express-News, began writing columns attacking the DRT for their care of the Alamo. According to him, the DRT had kept the temperature too low within the chapel, causing water vapor to form. The water vapor would then mix with car exhaust fumes and damage the limestone walls. These allegations prompted the legislature in 1993 to again attempt to transfer control of the Alamo to the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. At the same time, State Senator Gregory Luna filed a competing bill to transfer oversight of the Alamo to the Texas Historical Commission.[81]

By the following year, some advocacy groups in San Antonio had begun pressing for the mission to be turned into a larger historical park. They wished to restore the chapel to its 18th century appearance and focus the complex on its mission days rather than the activities of the Texas Revolution.[81] The DRT was outraged. The head of the group's Alamo Committee, Ana Hartman, claimed that the dispute was gender based. According to her, " "There's something macho about it. Some of the men who are attacking us just resent what has been a successful female venture since 1905."[82]

The dispute was mostly resolved in 1994, when then-governor George W. Bush vowed to veto any legislation that would displace the DRT as caretakers of the Alamo.[83] Later that year, the DRT erected a marker on the mission grounds recognizing that they had once served as Indian burial grounds.[84]

Modern use

As of 2002, the Alamo welcomed over four million visitors each year, making it one of the most popular historic sites in the United States.[85] Visitors may tour the chapel, as well as the Long Barracks, which contains a small museum with paintings, weapons, and other artifacts from the era of the Texas Revolution.[86] Additional artifacts are displayed in another complex building, alongside a large diorama that recreates the compound as it existed in 1836. A large mural, known as the Wall of History, portrays the history of the Alamo complex from its mission days to modern times.[2]

Although the governor's office receives annual audits of the site's financial records, for at least a decade under Rick Perry the audits have not been examined. The site has an annual budget of $5 million, primarily funded through sales in the gift store.[87]

In 2009 DRT commissioned the first land survey of the Alamo by Westar Alamo Land Surveyors, Inc. which was signed by Registered Professional Land Surveyor Jose A. Trevino in November 2009.[88]

See also

Notes

- ^ Mason lists the number as 52. Mason (1974), p. 56.

- ^ The only exception was the body of Gregorio Esparza, whose brother, Francisco Esparza, served in Santa Anna's army and received permission to give Gregorio a proper burial. Edmondson (2000), p. 374.

- ^ Mason believes that the remaining missions in San Antonio, as well as Presidio la Bahia in Goliad, Texas, are in a similar category to the Alamo building. Mason (1974), p. 71.

References

- ^ ["National[dead link]][dead link] Register Information System"], National Register of Historic Places (National Park Service), 2006-03-15, [http://www.nr.nps.gov/, retrieved 2009-02-20

- ^ a b Thompson (2002), p. 119.

- ^ Heintzelman (May, 1975) (PDF), National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination: Spanish Governor's Palace, National Park Service, http://pdfhost.focus.nps.gov/docs/NHLS/Text/66000808.pdf, retrieved 2009-06-22 and [1]PDF (852 KB)

- ^ Texas Historic Atlas

- ^ Chipman (1992), pp. 113, 116.

- ^ a b c Webet (1992), p. 163.

- ^ a b c d Chipman (1992), p. 117.

- ^ a b Mason (1974), p. 43.

- ^ a b Mason (1974, p. 45.

- ^ a b c Mason (1974), p. 44.

- ^ a b c d e Thompson (2002), p 18.

- ^ a b c d e Schoelwer (1985), p. 23.

- ^ a b c Schoelwer (1985), p. 22.

- ^ a b Thompson (2002), p. 19.

- ^ Schoelwer (1985), p. 24.

- ^ Mason (1974), p. 58.

- ^ Chipman (1992), p. 202.

- ^ a b Schoelwer (1985), p. 29.

- ^ Schoelwer (1985), p. 26.

- ^ Mason (1974), p. 61.

- ^ Todish et al. (1998), p. 10.

- ^ a b c Thompson (2002), p. 20.

- ^ a b Hardin (1994), p. 111.

- ^ Lord (1961), p. 59.

- ^ Barr (1990), p. 64.

- ^ Hardin (1994), p. 91.

- ^ Todish et al. (1998), p. 29.

- ^ Todish et al. (1998), p. 30.

- ^ a b Todish et al. (1998), p. 31.

- ^ Hopewell (1994), p. 114.

- ^ Todish et al. (1998), p. 32.

- ^ Hardin (1994), p. 120.

- ^ Todish et al. (1998), p. 40.

- ^ Nofi (1992), p. 102.

- ^ Todish et al. (1998), p. 53.

- ^ Edmondson (2000), p. 370.

- ^ a b Hardin (1994), p. 147.

- ^ Petite (1998), p. 114.

- ^ Todish et al. (1998), p. 54.

- ^ Petite (1998), p. 115.

- ^ a b Edmondson (2000), p. 371.

- ^ Tinkle (1985), p. 216.

- ^ Edmondson (2000), p. 374.

- ^ Edmondson (2000), p. 407.

- ^ Groneman (1990), p. 119.

- ^ a b Todish et al. (1998), p. 55.

- ^ Hardin (1961), p. 155.

- ^ Nofi (1992), p. 136.

- ^ Thompson (2002), p. 102.

- ^ a b c Roberts and Olson (2001), p. 200.

- ^ a b Thompson (2002), p. 103.

- ^ a b Schoelwer (1985), p. 32.

- ^ a b c d Roberts and Olson (2001), p. 201.

- ^ a b Thompson (2002), p. 104.

- ^ a b Schoelwer (1985), p. 38.

- ^ March 23, 1861 issue, Harpers Weekly

- ^ a b Roberts and Olson (2001), p. 202.

- ^ Schoelwer (1985), p. 40.

- ^ Roberts and Olson (2001), p. 206.

- ^ Roberts and Olson (2001), p. 207.

- ^ Roberts and Olson (2001), p. 208.

- ^ a b c Roberts and Olson (2001), p. 209.

- ^ Roberts and Olson (2001), p. 210.

- ^ a b Roberts and Olson (2001), p. 211.

- ^ Roberts and Olson (2001), p. 198.

- ^ Roberts and Olson (2001), p. 197.

- ^ a b Roberts and Olson (2001), p. 212.

- ^ a b c Roberts and Olson (2001), p. 213.

- ^ a b Roberts and Olson (2001), p. 214.

- ^ Roberts and Olson (2001), p. 221.

- ^ Roberts and Olson (222).

- ^ Roberts and Olson (2001), p. 225.

- ^ Roberts and Olson (2001), pp. 227, 229.

- ^ "Walter Eugene George, Jr. Collection: 1951-2007", Alexander Architectural Archive, University of Texas at Austin Libraries. Retrieved 2010-11-29.

- ^ Schoelwer (1985), p. 59.

- ^ Mason (1974), p. 71.

- ^ Mason (1974), p. 78.

- ^ Roberts and Olson (2001), p. 301.

- ^ Roberts and Olson (2001), pp. 303–4.

- ^ a b c Roberts and Olson (2001), p. 304.

- ^ a b Roberts and Olson (2001), p. 307.

- ^ Roberts and Olson (2001), p. 308.

- ^ Roberts and Olson (2001), p. 309.

- ^ Roberts and Olson (2001), p. 310.

- ^ Thompson (2002), p. 108.

- ^ Thompson (2002), p. 121.

- ^ Korn, Marjorie (August 24, 2009), "Hutchison wants more state oversight over Alamo", Houston Chronicle: Section B, pp. 2–3, http://www.chron.com/CDA/archives/archive.mpl?id=2009_4780432, retrieved 2009-09-07

- ^ 86

Sources

- Barr, Alwyn (1996), Black Texans: A history of African Americans in Texas, 1528–1995 (2nd ed.), Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, ISBN 0-8061-2878-X, OCLC 34742519

- Chipman, Donald E. (1992), Spanish Texas, 1519–1821, Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, ISBN 0-292-77659-4, OCLC 25411908

- Edmondson, J.R. (2000), The Alamo Story-From History to Current Conflicts, Plano, TX: Republic of Texas Press, ISBN 1-55622-678-0, OCLC 42842410

- Groneman, Bill (1990), Alamo Defenders, A Genealogy: The People and Their Words, Austin, TX: Eakin Press, ISBN 0-89015-757-X, OCLC 20670456

- Hardin, Stephen L. (1999), Texian Iliad, Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, ISBN 0-292-73086-1, OCLC 29704011

- Hopewell, Clifford (1994), James Bowie Texas Fighting Man: A Biography, Austin, TX: Eakin Press, ISBN 0-89015-881-9, OCLC 27223654

- Lord, Walter (1978), A Time to Stand, Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, ISBN 0-8032-7902-7, OCLC 3893089

- Mason, Herbert Molloy, Jr. (1974), Missions of Texas, Birmingham, AL: Southern Living Books

- Nofi, Albert A. (1992), The Alamo and the Texas War of Independence, September 30, 1835 to April 21, 1836: Heroes, Myths, and History, Conshohocken, PA: Combined Books, Inc., ISBN 0-938289-10-1, OCLC 25833554

- Petite, Mary Deborah (1999), 1836 Facts about the Alamo and the Texas War for Independence, Mason City, IA: Savas Publishing Company, ISBN 1-882810-35-X, OCLC 41545196

- Roberts, Randy; Olson, James S. (2001), A Line in the Sand: The Alamo in Blood and Memory, The Free Press, ISBN 0-684-83544-4, OCLC 223395265

- Schoelwer, Susan Prendergast (1985), Alamo Images: Changing Perceptions of a Texas Experience, Dallas, TX: The DeGlolyer Library and Southern Methodist University Press, ISBN 0-87074-213-2, OCLC 12419738

- Thompson, Frank (2005), The Alamo, Denton, TX: University of North Texas Press, ISBN 1-57441-194-2, OCLC 58480792

- Todish, Timothy J.; Todish, Terry; Spring, Ted (1997), Alamo Sourcebook, 1836: A Comprehensive Guide to the Battle of the Alamo and the Texas Revolution, Austin, TX: Eakin Press, ISBN 978-1-57168-152-2, OCLC 36783795

- Weber, David J. (1992), The Spanish Frontier in North America, Yale Western Americana Series, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-05198-0, OCLC 185691787

Further reading

- Thompson, Frank (2001), The Alamo: A Cultural History, Taylor Publishing, ISBN 978-0-87833-254-0, OCLC 45463410

External links

- Daughters of the Republic of Texas: Welcome to the Alamo

- Alamo Handbook of Texas Online

- National Historic Landmarks Program: Alamo

Battle of the Alamo Siege Legacy Remember the Alamo (song) · The Alamo: Shrine of Texas Liberty (1938) · Davy Crockett, King of the Wild Frontier (1954) · The Last Command (1955) · The Alamo (1960) · The Alamo: Thirteen Days to Glory (1987) · The Alamo (2004)Defenders Texian survivors Mexican commanders See also Alamo MissionU.S. National Register of Historic Places Topics Lists by states Alabama • Alaska • Arizona • Arkansas • California • Colorado • Connecticut • Delaware • Florida • Georgia • Hawaii • Idaho • Illinois • Indiana • Iowa • Kansas • Kentucky • Louisiana • Maine • Maryland • Massachusetts • Michigan • Minnesota • Mississippi • Missouri • Montana • Nebraska • Nevada • New Hampshire • New Jersey • New Mexico • New York • North Carolina • North Dakota • Ohio • Oklahoma • Oregon • Pennsylvania • Rhode Island • South Carolina • South Dakota • Tennessee • Texas • Utah • Vermont • Virginia • Washington • West Virginia • Wisconsin • WyomingLists by territories Lists by associated states Other  Category:National Register of Historic Places •

Category:National Register of Historic Places •  Portal:National Register of Historic PlacesCategories:

Portal:National Register of Historic PlacesCategories:- NRHP articles with dead external links

- Historic district contributing properties

- Buildings and structures in San Antonio, Texas

- National Historic Landmarks in Texas

- History of San Antonio, Texas

- Shrines

- Spanish missions in Texas

- Texas Revolution

- Mexican-American War forts

- Visitor attractions in San Antonio, Texas

- Buildings and structures completed in 1744

- Buildings of religious function on the National Register of Historic Places in Texas

- Museums in San Antonio, Texas

- History museums in Texas

- Individually listed contributing properties to historic districts on the National Register

- Works Progress Administration in Texas

- Spanish Colonial architecture in Texas

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.