- History of coal mining

-

Due to its abundance, coal has been mined in various parts of the world throughout history and continues to be an important economic activity today. Compared to wood fuels, coal yields a higher amount of energy per mass and could be obtained in areas where wood is not readily available. Though historically used as a means of household heating, coal is now mostly used in industry, especially in smelting and alloy production, as well as electricity generation.

Large-scale coal mining developed during the Industrial Revolution, and coal provided the main source of primary energy for industry and transportation in the West from the 18th century to the 1950s. Coal remains an important energy source, due to its low cost and abundance when compared to other fuels, particularly for electricity generation.[1] However, coal is also mined today on a large scale by open pit methods wherever the coal strata strike the surface and is relatively shallow.

Britain developed the main techniques of underground coal mining from the late 18th century onward with further progress being driven by 19th century and early 20th century progress.[1]

However oil and its associated fuels began to be used as alternative from this time onward. By the late 20th century coal was for the most part replaced in domestic as well as industrial and transportation usage by oil, natural gas or electricity produced from oil, gas, nuclear power or renewable energy sources.

Since 1890, coal mining has also been a political and social issue. Coal miners' labour and trade unions became powerful in many countries in the 20th century, and often the miners were leaders of the Left or Socialist movements (as in Britain, Germany, Poland, Japan, Canada and the U.S.)[2] Since 1970, environmental issues have been increasingly important, including the health of miners, destruction of the landscape from strip mines and mountaintop removal, air pollution, and coal combustion's contribution to global warming.

Contents

Early history

Early coal extraction was small-scale, the coal lying either on the surface, or very close to it. Typical methods for extraction included drift mining and bell pits. As well as drift mines, small scale shaft mining was used. This took the form of a bell pit, the extraction working outward from a central shaft, or a technique called room and pillar in which 'rooms' of coal were extracted with pillars left to support the roofs. Both of these techniques however left considerable amount of usable coal behind.

The earliest reference to the use of coal in metalworking is found in the geological treatise On stones (Lap. 16) by the Greek scientist Theophrastus (c. 371–287 BC):

The earliest known use of coal in the Americas was by the Aztecs who used coal for fuel and jet (a type of lignite) for ornaments.[4]

In Roman Britain, the Romans were exploiting all major coalfields (save those of North and South Staffordshire) by the late 2nd century AD.[5] While much of its use remained local, a lively trade developed along the North Sea coast supplying coal to Yorkshire and London.[5] This also extended to the continental Rhineland, where bituminous coal was already used for the smelting of iron ore.[5] It was used in hypocausts to heat public baths, the baths in military forts, and the villas of wealthy individuals. Excavation has revealed coal stores at many forts along Hadrian's Wall, as well as the remains of a smelting industry at forts such as Longovicium nearby.[citation needed]

After the Romans left Britain, in AD 410, there are no records of coal being used in the country until the end of the 12th century. Shortly after the signing of the Magna Carta, in 1215, coal began to be traded in areas of Scotland and the north-east England, where the carboniferous strata where exposed on the sea shore, and thus became known as "sea coal". This commodity, however, was not suitable for use in the type of domestic hearths then in use, and was mainly used by artisans for lime burning, metal working and smelting. As early as 1228, sea coal from the north-east was being taken to London.[6]:5 During the 13th century, the trading of coal increased across Britain and by the end of the century most of the coalfields in England, Scotland and Wales were being worked on a small scale.[6]:8 As the use of coal amongst the artisans became more widespread, it became clear that coal smoke was detrimental to health and the increasing pollution in London led to much unrest and agitation. As a result of this, a Royal proclamation was issued in 1306 prohibiting artificers of London from using sea coal in their furnaces and commanding them to return to the traditional fuels of wood and charcoal.[6]:10 During the first half of the 14th century coal began to be used for domestic heating in coal producing areas of Britain, as improvements were made in the design of domestic hearths.[6]:13 Edward III was the first king to take an interest in the coal trade of the north east, issuing a number of writs to regulate the trade and allowing the export of coal to Calais.[6]:15 The demand for coal steadily increased in Britain during the 15th century, but it was still mainly being used in the mining districts, in coastal towns or being exported to continental Europe.[6]:19 However, by the middle of the 16th century supplies of wood were beginning to fail in Britain and the use of coal as a domestic fuel rapidly expanded.[6]:22

In 1575, Sir George Bruce of Carnock of Culross, Scotland, opened the first coal mine to extract coal from a "moat pit" under the sea on the Firth of Forth. He constructed an artificial loading island into which he sank a 40 ft shaft that connected to another two shafts for drainage and improved ventilation. The technology was far in advance of any coal mining method in the late medieval period and was considered one of the industrial wonders of the age.[7]

During the 17th century a number of advances in mining techniques were made, such the use of test boring to find suitable deposits and chain pumps, driven by water wheels, to drain the collieries.[6]:57–9

Coal deposits were discovered by colonists in Eastern North America in the 18th century.[4]

The Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution, which began in Britain in the 18th century, and later spread to continental Europe, North America, and Japan, was based on the availability of coal to power steam engines. International trade expanded exponentially when coal-fed steam engines were built for the railways and steamships in the 1810-1840 Victorian era. Coal was cheaper and much more efficient than wood fuel in most steam engines. As central and Northern England contains an abundance of coal, many mines were situated in these areas as well as the South Wales coalfield and Scotland. The small-scale techniques were unsuited to the increasing demand, with extraction moving away from surface extraction to deep shaft mining as the Industrial Revolution progressed.[8]

Beginning of the 20th century

Coal Production of the World, around 1905[9] Country Year Short Tons Europe United Kingdom 1905 236,128,936 Germany (coal) 121,298,167 Germany (lignite) 52,498,507 France 35,869,497 Belgium 21,775,280 Austria (coal) 12,585,263 Austria (lignite) 22,692,076 Hungary (coal) 1904 1,031,501 Hungary (lignite) 5,447,283 Spain 1905 3,202,911 Russia 1904 19,318,000 Netherlands 466,997 Bosnia (lignite) 540,237 Romania 110,000 Serbia 1904 183,204 Italy (coal and lignite) 1905 412,916 Sweden 322,384 Greece (lignite) 1904 466,997 Asia India 1905 8,417,739 Japan 1903 10,088,845 Sumatra 1904 207,280 Africa Transvaal 1904 2,409,033 Natal 1905 1,129,407 Cape Colony 1904 154,272 America United States 1905 350,821,000 Canada 1904 7,509,860 Mexico 700,000 Peru 1905 72,665 Australasia New South Wales 1905 6,632,138 Queensland 529,326 Victoria 153,135 Western Australia 127,364 Tasmania 51,993 New Zealand 1,585,756 United Kingdom

Pre 1900

Although some deep mining took place as early as the late Tudor period (in the North East, and along the Firth of Forth coast)[10][11] deep shaft mining in the UK began to develop extensively in the late 18th century, with rapid expansion throughout the 19th century and early 20th century when the industry peaked. The location of the coalfields helped to make the prosperity of Lancashire, of Yorkshire, and of South Wales; the Yorkshire pits which supplied Sheffield were only about 300 feet deep. Northumberland and Durham were the leading coal producers and they were the sites of the first deep pits. In much of Britain coal was worked from drift mines, or scraped off when it outcropped on the surface. Small groups of part-time miners used shovels and primitive equipment.

Scottish miners had been bonded to their "maisters" by a 1606 Act "Anent Coalyers and Salters". A Colliers and Salters (Scotland) Act 1775, recognised this to be "a state of slavery and bondage" and formally abolished it; this was made effective by a further Colliers (Scotland) Act 1799.[12][13]

Before 1800 a great deal of coal was left in places as extraction was still primitive. As a result in the deep Tyneside pits (300 to 1,000 ft deep) only about 40 percent of the coal could be extracted. The use of wooden pit props to support the roof was an innovation first introduced about 1800. The critical factor was circulation of air and control of dangerous explosive gases. At first fires were burned to create air currents and circulate air, but replaced by fans driven by steam engines. Protection for miners came with the invention of the Davy lamp and Geordie lamp, where any firedamp (or methane) burnt harmlessly within the lamp. It was achieved by restricting the ingress of air with either metal gauze or fine tubes, but the illumination from such lamps was very poor. Great efforts were made to develop better safe lamps, such as the Mueseler lamp produced in the Belgian pits near Liège.

Coal was so abundant in Britain that the supply could be stepped up to meet the rapidly rising demand. About 1770-1780 the annual output of coal was some 6¼ million long tons (or about the output of a week and a half in the 20th century). After 1790 output soared, reaching 16 million long tons by 1815 at the height of the Napoleonic War. The miners, less menaced by imported labour or machines than were the cotton mill workers, had begun to form trade unions and fight their grim battle for wages against the coal owners and royalty-lessees.[14]

Post-1900

Coal mining passed into Government control in 1947, although coal had been a political issue since the early part of the 20th century. The need to maintain coal supplies (a primary energy source) had figured in both world wars.[15] As well as energy supply, coal in the UK became a very political issue, due to conditions under which colliers worked and the way they were treated by colliery owners. Much of the 'old Left' of British politics can trace its origins to coal-mining areas, with the main labour union being the Miners' Federation of Great Britain, founded in 1888. The MFGB claimed 600,000 members in 1908. (The MFGB later became the more centralised National Union of Mineworkers).

Although other factors were involved, one cause of the UK General Strike of 1926 was concerns colliers had over very dangerous working conditions, reduced pay and longer shifts.

Technological development throughout the 19th and 20th centuries helped both to improve the safety of colliers and the productive capacity of collieries they worked. In the late 20th century, improved integration of coal extraction with bulk industries such as electrical generation helped coal maintain its position despite the emergence of alternative energies supplies such as oil, natural gas and, from the late 1950s, nuclear power used for electricity. More recently coal has faced competition from renewable energy sources and bio-fuels.

After World War II, the coal industry in Britain was nationalised, and remained in public ownership until the 1980s and the decline of the industry after the UK miners' strike (1984-1985). The 1980s and 1990s saw much change in the UK coal industry, with the industry contracting, in some areas quite drastically. Many pits were considered uneconomic[16] to work at then current wage rates compared to cheap North Sea oil and gas, and in comparison to subsidy levels in Europe. The Miners' Strike of 1984 failed to stop the Conservative government's plans under Margaret Thatcher to shrink the industry. The National Coal Board (by then British Coal), was privatised by selling off a large number of pits to private concerns through the mid 1990s, and the mining industry disappeared almost completely.[17]

In January 2008, the South Wales Valleys last deep pit mine, Tower Colliery in Hirwaun, Rhondda Cynon Taff closed with the loss of 120 jobs. The coal was exhausted.[18]

However, coal is still mined extensively at a number of deep pits in the Midlands and the North, and is extracted at several very large opencast pits in South Wales and elsewhere. There are proposals to re-open several deep pits with Russian capital[citation needed], owing to the soaring price of the commodity.

United States

Main article: History of coal mining in the United StatesAnthracite (or "hard" coal), clean and smokeless, became the preferred fuel in cities, replacing wood by about 1850. Bituminous (or "soft coal") mining came later. In the mid-century Pittsburgh was the principal market. After 1850 soft coal, which is cheaper but dirtier, came into demand for railway locomotives and stationary steam engines, and was used to make coke for steel after 1870.[19]

Total coal output soared until 1918; before 1890, it doubled every ten years, going from 8.4 million short tons in 1850 to 40 million in 1870, 270 million in 1900, and peaking at 680 million short tons in 1918. New soft coal fields opened in Ohio, Indiana and Illinois, as well as West Virginia, Kentucky and Alabama. The Great Depression of the 1930s lowered the demand to 360 million short tons in 1932.[20]

Under John L. Lewis, the United Mine Workers (UMW) became the dominant force in the coal fields in the 1930s and 1940s, producing high wages and benefits.[21] In 1914 at the peak there were 180,000 anthracite miners; by 1970 only 6,000 remained. At the same time steam engines were phased out in railways and factories, and bituminous was used primarily for the generation of electricity. Employment in bituminous peaked at 705,000 men in 1923, falling to 140,000 by 1970 and 70,000 in 2003. UMW membership among active miners fell from 160,000 in 1980 to only 16,000 in 2005, as coal mining became more mechanized and non-union miners predominated in the new coal fields.

In the 1960s a series of mergers saw coal production shift from small, independent coal companies to large, more diversified firms. Several oil companies and electricity producers acquired coal companies or leased Federal coal reserves in the west of the United States. Concerns that competition in the coal industry could decline as a result of these changes were heightened by a sharp rise in coal prices in the wake of the 1973 oil crisis. Coal prices fell in the 1980s, partly in response to oil price movements, but primarily in response to the large increase in supply worldwide which was brought about by the earlier price surge. During this period, the industry in the U.S. was characterized by a move towards low-sulfur coal.[22]

In 2008, competition was intense in the US coal mining industry with some U.S. mines approaching the end of their useful life mine closure. Other coal-producing countries also stepped up production to win a share of traditional US export markets.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the coal mining industry in the US in 2008 consisted of firms that mine bituminous coal, anthracite (both are types of black coal) and lignite (brown coal). Mining may be undertaken in a number of ways, including: underground mining (also known as bord and pillar mining), auger mining (where coal is extracted using a horizontal drilling technique), strip mining, culm bank (coal refuse pile) mining, and other surface mining. Census also classifies coal mining firms as those that also develop coal mine sites and prepare the coal for sale by washing, screening and sizing it.[23]

West Virginia

In 1883, thousands of European immigrants and a large number of African Americans migrated to southern West Virginia to work in coal mines. These coal miners worked in company mines with company tools and equipment, which they were required to lease. Along with these expenses, the miners were deducted pay for housing rent and items they purchased from company stores. Furthermore, the coal companies went as far as creating their own monetary system so the miners could only shop at company owned stores.[24]

In addition with the poor economic condition, safety in the mines was a great concern. West Virginia fell behind other states in regulating mining conditions. Between 1890 and 1912, West Virginia had a higher mine death rate than any other state. In fact, West Virginia is the site of the worst coal mining disaster to date. With the Monongah Mine disaster of Monongah, West Virginia 6 December 1907. This explosion was caused by the ignition of methane gas (also called "firedamp"), which in turn ignited the coal dust. The lives of 362 men were lost in the underground explosion. As a result, this disaster impelled the United States Congress to create the Bureau of Mines.[25]

As a result to the poor working conditions and low wages, the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) was formed in Columbus, Ohio in 1890. Finally in 1902, the UMWA achieved recognition in West Virginia. Consequently by 1912, the union had lost control of this area. So when the UMWA miners on Paint Creek in Kanawha County demanded wages equal to those of other area mines, they were rejected. As a result, the miners walked off the job on April 18, 1912 beginning one of the most violent strikes in the nation’s history. After the Cabin Creek miners joined the Paint Creek miners it started the mining war of West Virginia.[24]

Australia

In 1984 Australia surpassed the US as the world's largest coal exporter. One-third of Australia's coal exports were shipped from the Hunter River region of New South Wales, where coal mining and transport had begun nearly two centuries earlier. Coal River was the first name given by British settlers to the Hunter River after coal was found there in 1795. In 1804 the Sydney-based administration established a permanent convict settlement near the mouth of the Hunter River to mine and load the coal, predetermining the town's future as a coal port by naming it Newcastle. Today, Newcastle, NSW, is the largest coal port in the world.

Canada

Canadian coal mining has been centred in Nova Scotia and Alberta, although the United States has been a major supplier for the industrial regions of Ontario. By 2000 about 19% of Canada's energy was supplied by coal, much of it imported from the U.S while Eastern Canadian ports import considerable coal from Venezuela.

Nova Scotia

The first coal mining in Canada began in the 18th century with small hand-dug mines close to the sea at Joggins, Nova Scotia and in the Sydney area of Cape Breton Island. Large scale coal mining began in the late 1830s when the General Mining Association (GMA), a group of English mining investors, obtained a coal mining monopoly in Nova Scotia. They imported the latest in mining technology including steam water pumps and railways to develop large mines in the Stellarton area of Pictou County, Nova Scotia, including the Foord Pit which was by 1866 was the deepest coal mine in the world.[26] Coal mining also developed in Springhill and Joggins in Cumberland County, Nova Scotia. After the GMA monoploy expired, the largest and longest lasting mines developed at Cape Breton in Nova Scotia. Nova Scotia was the major supplier of Canadian coal until 1945.[27] At its peak in 1949 25,000 miners dug 17 million metric tons of coal from Nova Scotian mines. The miners, who lived in company towns, became politically active in left-wing politics during labour struggles for safety and fair wages. Westray Mine near Stellarton closed in 1992 after an explosion killed 26 miners. All the subsurface mines were closed by 2001, although some open pit coal mining continues near Stellarton. The Nova Scotia Museum of Industry at Stellarton explores the history of mining in the province from its location on the site of the Foord Pit.

Alberta

Coal was easy to find in, what is now, Drumheller, Alberta, Canada. The Atlas Coal Mine National Historic Site has turned this coalfield into a museum. This museum interprets how the Blackfoot and Cree knew about the “black rock that burned.” After many explorers reported coal in the area, a handful of ranchers and homesteaders dug out the coal for their homes. Sam Drumheller started the coal rush in this area when he bought the land from a local rancher, which he then sold to the Canadian National Railway. Sam Drumheller also registered a coal mine. However, before his mine opened Jesse Gouge and Garnet Coyle beat him to it by opening the Newcastle Mine. Once the railroad was built thousands of people came to mine this area.

By the end of 1912, there were nine working coal mines: Newcastle, Drumheller, Midland, Rosedale, and Wayne. In years to follow more mines sprang up: Nacmine, Cambria, Willow Creek, Lehigh, and East Coulee. The timing of the Drumheller mine industry was “lucky” according to the Atlas National Historical Site. The miners union of North America had won the right for better working conditions. As a result, child labor laws were passed to prvent boys under 14 years old working underground.

Miner camps in this area were called “hell’s hole” because miners lived in tents and shacks. These camps were filled with drinking, gambling and watching fistfights as forms of recreation. As living conditions improved to little houses, more women joined the men and started families, improving life. With new activities such as hockey, baseball and theatre the camps were no longer “hell’s hole” but became “the wonder town of the west.”

Between 1911 and 1979, 139 mines were registered in the Drumheller Valley, only 34 were productive for many years. Unfortunately, the beginning of the end for the Drumheller’s mining industry was the Leduc Oil Strike of 1948. After this, natural gas was how family heated their homes in western Canada. As the demand for coal dropped, mines closed and communities suffered. Some communities, Willow Creek for example, completely vanished while others went from boomtowns to ghost towns.

Atlas#4 Mine shipped its last load of coal in 1979, after which the Atlas Coal Mine National Historic Site has preserved the last of the Drumheller mines. Also nearby East Coulee School Museum interprets the life of family in mine towns for its visitors.[28]

Germany

The first important mines appeared in the 1750s, in the valleys of the rivers Ruhr, Inde and Wurm where coal seams outcropped and horizontal adit mining was possible. In 1782 the Krupp family began operations near Essen. After 1815 entrepreneurs in the Ruhr Area, which then became part of Prussia took advantage of the tariff zone (Zollverein) to open new mines and associated iron smelters. New railroads were built by British [engineers around 1850. Numerous small industrial centres sprang up, focused on ironworks, using local coal. The iron and steel works typically bought mines, and erected coking ovens to supply their own requirements in coke and gas. These integrated coal-iron firms ("Huettenzechen") became numerous after 1854; after 1900 they became mixed firms called "Konzern."

The average output of a mine in 1850 was about 8,500 short tons; its employment about 64. By 1900, the average mine's output had risen to 280,000 and the employment to about 1,400. Total Ruhr coal output rose from 2.0 million short tons in 1850 to 22 in 1880, 60 in 1900, and 114 in 1913, on the verge of war. In 1932 output was down to 73 million short tons, growing to 130 in 1940. Output peaked in 1957 (at 123 million), declining to 78 million short tons in 1974.[29] End of 2010 five coal mines were producing in Germany.

Belgium

By 1830 when iron and later steel became important in Wallonia the Belgian coal industry had long been established, and used steam engines for pumping. The Belgian coalfield lay near the navigable River Meuse, so coal was shipped downstream to the ports and cities of the Rhine-Meuse-Scheldt delta. The opening of the Saint-Quentin Canal allowed coal to go by barge to Paris. The Belgian coalfield outcrops over most of its area, and the highly folded nature of the coal seams meant that surface occurrences of the coal were very abundant. Deep mines were not required at first so there were a large number of small operations. There was a complex legal system for concessions, often multiple layers had different owners. Entrepreneurs started going deeper and deeper (thanks to the good pumping system). In 1790, the maximum depth of mines was 220 meters (720 ft). By 1856, the average depth in the Borinage was 361 meters (1,184 ft), and in 1866, 437 meters (1,434 ft) and some pits had reached down 700 to 900 meters (2,300 to 3,000 ft); one was 1,065 meters (3,494 ft) deep, probably the deepest coal mine in Europe at this time. Gas explosions were a serious problem, and Belgium had high coal miner fatality rates. By the late 19th century the seams were becoming exhausted and the steel industry was importing some coal from the Ruhr.[30] The discovery of coal in 1900 by Andre Dumont in the Campine basin in the Belgian Province Limburg, prompted entepreneurs from Liege to open coal mines, mainly producing coal for the steel industry. An announced reorganisation of the Belgian coal mines in 1965 resulted in strikes and a revolt which lead to the death of two coal miners in 1966 at the Zwartberg mine. Coal was mined in the Liege basin until 1980, in the Southern Wallonian basin until 1984, and in the Campine basin until 1992.

Poland

The first permanent coal mine in Poland was established in Szczakowa near Jaworzno in 1767. In 19th century development of iron, copper and lead mining and processing in southern Poland (notably in the Old-Polish Industrial Region and later in the region of Silesia led to a quick development of coal mining. Among the most prominent deposits were located in what are now the Upper Silesian Industrial Region and Rybnik Coal Area (in late 19th century part of Prussia) and the Zagłębie Dąbrowskie on the Russian side of the border.

In modern times coal is still considered a strategic resource for Poland's economy, as it covers roughly 65% of energetic needs. Before and after World War II Poland has been one of the major coal producers worldwide, usually listed among the five largest. However, after 1989 the coal production is in decline, with the overall production for 1994 reaching 132 million metric tons, 112 million metric tons in 1999 and 104 million metric tons in 2002.

Chinese coal miners in an illustration of the Tiangong Kaiwu Ming Dynasty encyclopedia, published in 1637 by Song Yingxing.

Chinese coal miners in an illustration of the Tiangong Kaiwu Ming Dynasty encyclopedia, published in 1637 by Song Yingxing.

China

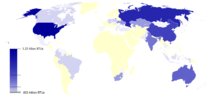

The industry in China goes back many centuries, but in recent decades has become the main energy source of what (from 2010) is the world's second largest economy.[31] Thus China is by far the largest producer of coal in the world, producing over 2.8 billion tons of coal in 2007, or approximately 39.8 percent of all coal produced in the world during that year.[32] For comparison, the second largest producer, the United States, produced more than 1.1 billion tons in 2007. An estimated 5 million people work in China's coal-mining industry. As many as 20,000 miners die in accidents each year.[33] Most Chinese mines are deep underground and do not produce the surface disruption typical of strip mines.

Disasters

Mining has always been dangerous, because of explosions, roof cave-ins, and the difficulty of mines rescue. The worst single disaster in British coal mining history was at Senghenydd in the South Wales coalfield. On the morning of 14 October 1913 an explosion and subsequent fire killed 436 men and boys. Only 72 bodies were recovered. It followed a series of many extensive Mining accidents in the Victorian era, such as The Oaks explosion of 1866 and the Hartley Colliery Disaster of 1862. Most of the explosions were caused by firedamp ignitions followed by coal dust explosions. Deaths were mainly caused by carbon monoxide poisoning, although at Hartley colliery, where the victims were entombed when the single shaft was blocked by a broken cast iron beam from the haulage engine, death occurred by asphyxiation.

The Courrières mine disaster, Europe's worst mining accident, caused the death of 1,099 miners (including many children) in Northern France on 10 March 1906. It seems that this disaster was surpassed only by the Benxihu Colliery accident in China on April 26, 1942, which killed 1,549 miners.[34]

As well as disasters directly affecting mines, there have been disasters attributable to the impact of mining on the surrounding landscapes and communities. The Aberfan disaster which destroyed a school in South Wales can be directly attributed to the collapse of spoil heaps from the town's colliery past.

See also

- Coal mining

- Mining disasters

- Child labour in coal mines

Notes

- ^ a b Freese. (2003)

- ^ Geoff Eley, Forging Democracy: The History of the Left in Europe, 1850-2000 (2002); Frederic Meyers, European Coal Mining Unions: structure and function (1961) P. 86; Kazuo and Gordon (1997) p 48; Hajo Holborn, History of Modern Germany (1959) p. 521; David Frank, J. B. McLachlan: A Biography: The Story of a Legendary Labour Leader and the Cape Breton Coal Miners, (1999) p, 69; David Montgomery, The fall of the house of labor: the workplace, the state, and American labor activism, 1865-1925 (1991) p 343.

- ^ Mattusch, Carol (2008): "Metalworking and Tools", in: Oleson, John Peter (ed.): The Oxford Handbook of Engineering and Technology in the Classical World, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-518731-1, pp. 418–38 (432).

- ^ a b Freese (2003).

- ^ a b c Smith, A. H. V. (1997): "Provenance of Coals from Roman Sites in England and Wales", Britannia, Vol. 28, pp. 297–324 (322–4).

- ^ a b c d e f g h Galloway (1882).

- ^ Brown, Ian, From Columba to the Union (Until 10707), The Edinburgh History of Scottish Literature.

- ^ Flinn and Stoker (1984)

- ^ Encyclopedia Britannica (11th ed.) online

- ^ "Papers on Mining in Scotland, 18th and 19th centuries". Archives Hub. http://www.archiveshub.ac.uk/news/02092505.html. Retrieved 2008-10-17.

- ^ "Culross". BBC. http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/scottishhistory/europe/trails_europe_culross.shtml. Retrieved 2008-10-17.

- ^ "Erskine May on Slavery in Britain (Vol. III, Chapter XI)". http://www.pdavis.nl/ErskineMay.htm. Retrieved 2009-07-20.

- ^ "Scottish Mining Website". Scottish Mining Website. http://www.scottishmining.co.uk/260.html. Retrieved 2009-07-20.

- ^ J. Steven Watson; The Reign of George III, 1760-1815. 1960. p, 516.

- ^ Fine (1990)

- ^ Margaret Thatcher, quoted in B. Fine, The coal question: political economy and industrial change from the Nineteenth Century to the present day

- ^ Fine (1990); Bridget Woodman, The Burning Question: Is the UK on Course for a Low Carbon Economy (2004)

- ^ BBC Coal mine closes with celebration 25 January 2008

- ^ Binder (1974)

- ^ Bruce C. Netschert and Sam H. Schurr, Energy in the American Economy, 1850-1975: An Economic Study of Its History and Prospects. pp 60-62.

- ^ Dubofsky and Van Tine (1977)

- ^ "Coal Mining Industry Report" IBISWorld, 2009

- ^ [1] "U.S Census Bureau, 2002

- ^ a b "West Virginia Division of Culture and History"

- ^ "United States Mine Rescue Association"

- ^ "History of the Site", Nova Scotia Museum of Industry

- ^ "Coal Mining", Nova Scotia Museum of Industry

- ^ [2] "Atlas Coal Mine National Historical Site"

- ^ Pounds (1952)

- ^ Parker and Pounds (1957)

- ^ Elspeth Thomson, The Chinese Coal Industry: An Economic History (2003)

- ^ "World Coal Production, Most Recent Estimates 1980-2007 (October 2008)". U.S. Energy Information Administration. 2008. http://www.eia.doe.gov/emeu/international/coalproduction.html. Retrieved 11-2-08.

- ^ "Where The Coal Is Stained With Blood." Time, March 2, 2007.

- ^ (French) "Marcel Barrois". Le Monde. March 10, 2006. http://www.lemonde.fr/web/article/0,1-0@2-3226,36-749532,0.html.

Bibliography

Britain

- W. Stanley Jevons: The Coal Question: An Inquiry Concerning the Progress of the Nation, and the Probable Exhaustion of Our Coal Mines (1865). online edition

- Galloway, Robert L. (1882). A History Of Coal Mining In Great Britain. London: Macmillan. OCLC 457542130.

- Edward Hull: The Coal-fields of Great Britain: Their History, Structure and Resources: With Descriptions (1905).

- Robert W Dron. The economics of coal mining (1928).

- George Orwell. Down the Mine (The Road to Wigan Pier chapter 2, 1937) full text

- Margot Heinemann: Britain's coal: A study of the mining crisis (1944).

- John Benson: British Coal-Miners in the Nineteenth Century: A Social History Holmes & Meier, (1980) online

- Robert Waller: The Dukeries Transformed: A history of the development of the Dukeries coal field after 1920 (OUP 1983).

- Michael W. Flinn, and David Stoker. History of the British Coal Industry: Volume 2. 1700-1830: The Industrial Revolution (1984).

- B. Fine. The Coal Question: Political Economy and Industrial Change from the Nineteenth Century to the Present Day (1990).

- Carolyn Baylies: The History of the Yorkshire Miners, 1881-1918 Routledge (1993).

- John Hatcher: The History of the British Coal Industry: Volume 1: Before 1700: Towards the Age of Coal (1993).

- James Alan Jaffe: The Struggle for Market Power: Industrial Relations in the British Coal Industry, 1800-1840 (2003).

United States

Pre-World War II mechanization

- ^ Green, James R., The Business History Review-Book Review: What's a Coal Miner to Do? The Mechanization of Coal Mining by Keith Dix, (Harvard College: The President and Fellowes of Harvard College, Spring 1991), 183-185

- ^ Myers, Mark, “Coal Mechanization and Migration from McDowell County, West Virginia, 1932-1970: A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Department of History East Tennessee State University,” (August 2001), 1-4, 67-60

Industry

- Sean Patrick Adams, . "The US Coal Industry in the Nineteenth Century." EH.Net Encyclopedia, August 15, 2001 scholarly overview

- Sean Patrick Adams, Old Dominion, Industrial Commonwealth: Coal, Politics, and Economy in Antebellum America. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004.

- Frederick Moore Binder, Coal Age Empire: Pennsylvania Coal and Its Utilization to 1860. Harrisburg: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, 1974.

- Alfred Chandler, . "Anthracite Coal and the Beginnings of the ‘Industrial Revolution' in the United States", Business History Review 46 (1972): 141-181.

- Carmen., DiCiccio, Coal and Coke in Pennsylvania. Harrisburg: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, 1996

- Phil Conley, History of West Virginia Coal Industry (Charleston: Education Foundation, 1960)

- Howard Eavenson, . The First Century and a Quarter of the American Coal Industry 1942.

- Verla R. Flores and A. Dudley Gardner. Forgotten Frontier: A History of Wyoming Coal Mining (1989)

- Fred J. Lauver, "A Walk Through the Rise and Fall of Anthracite Might", Pennsylvania Heritage Magazine 27#1 (2001) online edition

- Priscilla Long, Where the Sun Never Shines: A History of America's Bloody Coal Industry Paragon, 1989.

- Robert H. Nelson. The Making of Federal Coal Policy (1983)

- Bruce C. Netschert and Sam H. Schurr, Energy in the American Economy, 1850-1975: An Economic Study of Its History and Prospects. (1960) online

- Glen Lawhon Parker, The Coal Industry: A Study in Social Control (Washington: American Council on Public Affairs, 1940)

- H. Benjamin Powell, Philadelphia's First Fuel Crisis. Jacob Cist and the Developing Market for Pennsylvania Anthracite. The Pennsylvania State University Press, 1978.

- Dan Rottenberg, In the Kingdom of Coal: An American Family and the Rock That Changed the World (2003), owners' perspective

- Sam H. Schurr, and Bruce C. Netschert. Energy in the American Economy, 1850-1975: An Economic Study of Its History and Prospects. Johns Hopkins Press, 1960.

- United States Anthracite Coal Strike Commission, 1902–1903, Report to the President on the Anthracite Coal Strike of May–October, 1902 By United States Anthracite Coal Strike (1903) online edition

- Richard H. K. Vietor and Martin V. Melosi; Environmental Politics and the Coal Coalition Texas A&M University Press, 1980 online

- Kenneth Warren, Triumphant Capitalism: Henry Clay Frick and the Industrial Transformation of America. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1996.

Coal miners and unions

- Harold W Aurand. Coalcracker Culture: Work and Values in Pennsylvania Anthracite, 1835-1935 2003

- Morton S. Baratz, The Union and the Coal Industry (Yale University Press, 1955)

- Perry Blatz, Democratic Miners: Work and Labor Relations in the Anthracite Coal Industry, 1875-1925. Albany: SUNY Press, 1994.

- David Alan Corbin, Life, Work, and Rebellion in the Coal Fields: The Southern West Virginia Miners, 1880-1922 (1981)

- Keith Dix, What's a Coal Miner to Do? The Mechanization of Coal Mining (1988), changes in the coal industry prior to 1940

- Melvyn Dubofsky and Warren Van Tine, John L. Lewis: A Biography (1977), leader of Mine Workers union, 1920–1960

- Coal Mines Administration, U.S, Department Of The Interior. A Medical Survey of the Bituminous-Coal Industry. U.S. Government Printing Office. 1947. online

- Ronald D, Eller. Miners, Millhands, and Mountaineers: Industrialization of the Appalachian South, 1880–1930 1982.

- Price V. Fishback. Soft Coal, Hard Choices: The Economic Welfare of Bituminous Coal Miners, 1890-1930 (1992)

- Jonathan Grossman "The Coal Strike of 1902 – Turning Point in U.S. Policy" Monthly Labor Review October 1975. online

- Katherine Harvey, The Best Dressed Miners: Life and Labor in the Maryland Coal Region, 1835-1910. Cornell University Press, 1993.

- A. F. Hinrichs; The United Mine Workers of America, and the Non-Union Coal Fields Columbia University, 1923 online

- Herman R. Lantz; People of Coal Town Columbia University Press, 1958; on southern Illinois; online

- John H.M. Laslett, ed. The United Mine Workers: A Model of Industrial Solidarity? Penn State University Press, 1996.

- Ronald L. Lewis. Black Coal Miners in America: Race, Class, and Community Conflict. University Press of Kentucky, 1987.

- Richard D. Lunt, Law and Order vs. the Miners: West Virginia, 1907-1933 Archon Books, 1979, On labor conflicts of the early 20th century.

- Edward A. Lynch and David J. McDonald. Coal and Unionism: A History of the American Coal Miners' Unions (1939)

- Phelan, Craig. Divided Loyalties: The Public and Private Life of Labor Leader John Mitchell (1994)

- Jörg Rössel, Industrial Structure, Union Strategy and Strike Activity in Bituminous Coal Mining, 1881 - 1894, in: Social Science History 26 (2002): 1 - 32.

- Curtis Seltzer, Fire in the Hole: Miners and Managers in the American Coal Industry University Press of Kentucky, 1985, conflict in the coal industry to the 1980s.

- Joe William Trotter Jr., Coal, Class, and Color: Blacks in Southern West Virginia, 1915-32 (1990)

- U.S. Immigration Commission, Report on Immigrants in Industries, Part I: Bituminous Coal Mining, 2 vols. Senate Document no. 633, 61st Cong., 2nd sess. (1911)

- Anthony F.C. Wallace, St. Clair. A Nineteenth-Century Coal Town's Experience with a Disaster-Prone Industry. Knopf, 1981.

- Robert D. Ward and William W. Rogers, Labor Revolt in Alabama: The Great Strike of 1894 University of Alabama Press, 1965 online coal strike

World

- Dorian, James P. Minerals, Energy, and Economic Development in China Clarendon Press, 1994

- David Frank, J. B. McLachlan: A Biography: The Story of a Legendary Labour Leader and the Cape Breton Coal Miners, (1999), in Canada

- Barbara Freese. Coal: A Human History (2003)

- Jeffrey, E. C. Coal and Civilization 1925.

- Nimura Kazuo, Andrew Gordon, and Terry Boardman; The Ashio Riot of 1907: A Social History of Mining in Japan Duke University Press, 1997

- Martin F. Parnell; The German Tradition of Organized Capitalism: Self-Government in the Coal Industry Oxford University Press Inc., 1998 online

- Marsden, Susan, 'Coals to Newcastle: a History of Coal Loading at the Port of Newcastle, New South Wales 1797-1997' (2002) ISBN 0-9578961-9-0.

- Norman J. G. Pounds and William N. Parker; Coal and Steel in Western Europe; the Influence of Resources and Techniques on Production Indiana University Press, 1957 online

- Norman J. G. Pounds "An Historical Geography of Europe, 1800-1914 (1993)

- Norman J. G. Pounds. The Ruhr: A Study in Historical and Economic Geography (1952) online

- Huaichuan Rui; Globalisation, Transition and Development in China: The Case of the Coal Industry Routledge, 2004 online

- Elspeth Thomson; The Chinese Coal Industry: An Economic History Routledge 2003 online.

- World Coal Institute. The Coal Resource (2005) covers all aspects of the coal industry in 48 pp; online version

External links

- "Illawarra Coal" - An unofficial history of coal mining in the Illawarra region of Australia

- Encyclopedia britannica 11th ed 1913

- World Coal Institute on current issues

- Abandoned mine Research

- Mining History Network numerous links (many are broken)

- Coal mining in Wales

- Down the Mine — George Orwell essay on a visit to a coal mine.

- Workplace Fatality’s & the Aftermath United Support & Memorial for Workplace Fatalities

- Workplace Fatality’s & the Aftermath Weekly Toll Blog

- Historic Images of Philadelphia and Reading Coal and Iron Company Courtesy of the Hagley Library Digital Archives

Coal in nature Coal by grade Coal combustion Coal mining Coal types are ordered by grade. 1: peat is considered a precursor to coal, while graphite is only technically considered a coal typeCategories:- Coal mining

- Industrial Revolution

- History of mining

- Industrial Workers of the World

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.