- Listeriosis

-

Listeriosis Classification and external resources

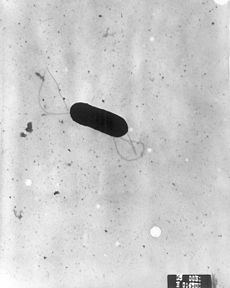

Listeria monocytogenesICD-10 A32 ICD-9 027.0 DiseasesDB 7503 MedlinePlus 001380 eMedicine med/1312 ped/1319 Listeriosis is a bacterial infection caused by a Gram-positive, motile bacterium, Listeria monocytogenes.[1] Listeriosis is relatively rare and occurs primarily in newborn infants, elderly patients, and patients who are immunocompromised.[2]

The symptoms of listeriosis usually last 7–10 days, with the most common symptoms being fever, muscle aches, and vomiting. Diarrhea is another, but less common symptom. If the infection spreads to the nervous system it can cause meningitis, an infection of the covering of the brain and spinal cord. Symptoms of meningitis are headache, stiff neck, confusion, loss of balance, and convulsions.[3][4]

Listeriosis has a very low incidence in humans. However, pregnant women are much more likely than the rest of the population to contract it. Infected pregnant women may have only mild, flulike symptoms. However, infection in a pregnant woman can lead to early delivery, infection of the newborn, and death of the baby.[3] It seems that Listeria originally evolved to invade membranes of the intestines, as an intracellular infection, and developed a chemical mechanism to do so. This involves a bacterial protein " internalin" which attaches to a protein on the intestinal cell membrane " cadherin." These adhesion molecules are also to be found in two other unusually tough barriers in humans - the blood brain barrier and the feto - placental barrier, and this may explain the apparent affinity that Listeria has for causing meningitis and affecting babies in-utero.

In veterinary medicine, listeriosis can be a quite common condition in some farm outbreaks. It can also be found in wild animals; see listeriosis in animals.

Contents

Signs and symptoms

The disease primarily affects older adults, persons with weakened immune systems, pregnant women, and newborns. Rarely, persons without these risk factors can also be affected. A person with listeriosis usually has fever and muscle aches, often preceded by diarrhea or other gastrointestinal symptoms. Almost everyone who is diagnosed with listeriosis has invasive infection (meaning that the bacteria spread from their intestines to their blood stream or other body sites). Disease may occur as much as two months after eating contaminated food.

The symptoms vary with the infected person:

- High-risk persons other than pregnant women: Symptoms can include fever, muscle aches, headache, stiff neck, confusion, loss of balance, and convulsions.

- Pregnant women: Pregnant women typically experience only a mild, flu-like illness. However, infections during pregnancy can lead to miscarriage, stillbirth, premature delivery, or life-threatening infection of the newborn.

- Previously healthy persons: People who were previously healthy but were exposed to a very large dose of Listeria can develop a non-invasive illness (meaning that the bacteria have not spread into their blood stream or other body sites). Symptoms can include diarrhea and fever.

If a person has eaten food contaminated with Listeria and does not have any symptoms, most experts believe that no tests or treatment are needed, even for persons at high risk for listeriosis.[5]

Cause

Listeria monocytogenes is ubiquitous in the environment. The main route of acquisition of Listeria is through the ingestion of contaminated food products. Listeria has been isolated from raw meat, dairy products, vegetables, fruit and seafood. Soft cheeses, unpasteurized milk and unpasteurised pâté are potential dangers; however, some outbreaks involving post-pasteurized milk have been reported.[1]

Rarely listeriosis may present as cutaneous listeriosis. This infection occurs after direct exposure to L. monocytogenes by intact skin and is largely confined to veterinarians who are handling diseased animals, most often after a listerial abortion.[6]

Diagnosis

Listeria monocytogenes grown on Biorad RAPID'L.Mono Agar

Listeria monocytogenes grown on Biorad RAPID'L.Mono Agar

In CNS infection cases, L. monocytogenes can often be cultured from the blood, and always cultured from the CSF. There are no reliable serological or stool tests.

Prevention

The main means of prevention is through the promotion of safe handling, cooking and consumption of food. This includes washing raw vegetables and cooking raw food thoroughly, as well as reheating leftover or ready-to-eat foods like hot dogs until steaming hot.[7]

Another aspect of prevention is advising high-risk groups such as pregnant women and immunocompromised patients to avoid unpasteurized pâtés and foods such as soft cheeses like feta, Brie, Camembert cheese, and bleu. Cream cheeses, yogurt, and cottage cheese are considered safe. In the United Kingdom, advice along these lines from the Chief Medical Officer posted in maternity clinics led to a sharp decline in cases of listeriosis in pregnancy in the late 1980s.[8]

Treatment

Bacteremia should be treated for 2 weeks, meningitis for 3 weeks, and brain abscess for at least 6 weeks. Ampicillin generally is considered antibiotic of choice; gentamicin is added frequently for its synergistic effects. Overall mortality rate is 20–30%; of all pregnancy-related cases, 22% resulted in fetal loss or neonatal death, but mothers usually survive.[9][citation needed].

Epidemiology

Stages in the intracellular life-cycle of Listeria monocytogene. (Center) Cartoon depicting entry, escape from a vacuole, actin nucleation, actin-based motility, and cell-to-cell spread. (Outside) Representative electron micrographs from which the cartoon was derived. LLO, PLCs, and ActA are all described in the text. The cartoon and micrographs were adapted from Tilney and Portnoy (1989).

Stages in the intracellular life-cycle of Listeria monocytogene. (Center) Cartoon depicting entry, escape from a vacuole, actin nucleation, actin-based motility, and cell-to-cell spread. (Outside) Representative electron micrographs from which the cartoon was derived. LLO, PLCs, and ActA are all described in the text. The cartoon and micrographs were adapted from Tilney and Portnoy (1989).

Incidence in 2004–2005 was 2.5–3 cases per million population a year in the United States, where pregnant women accounted for 30% of all cases.[10] Of all nonperinatal infections, 70% occur in immunocompromised patients. Incidence in the U.S. has been falling since the 1990s, in contrast to Europe where changes in eating habits have led to an increase during the same time. In Sweden, it has stabilized at around 5 cases per annum per million population, with pregnant women typically accounting for 1–2 of some 40 total yearly cases.[11]

There are four distinct clinical syndromes:

- Infection in pregnancy: Listeria can proliferate asymptomatically in the vagina and uterus. If the mother becomes symptomatic, it is usually in the third trimester. Symptoms include fever, myalgias, arthralgias and headache. Miscarriage, stillbirth and preterm labor are complications of this infection. Symptoms last 7–10 days.

- Neonatal infection (granulomatosis infantisepticum): There are two forms. One, an early-onset sepsis, with Listeria acquired in utero, results in premature birth. Listeria can be isolated in the placenta, blood, meconium, nose, ears, and throat. Another, late-onset meningitis is acquired through vaginal transmission, although it also has been reported with caesarean deliveries.

- Central nervous system (CNS) infection: Listeria has a predilection for the brain parenchyma, especially the brain stem, and the meninges. It can cause cranial nerve palsies, encephalitis, meningitis, meningoencephalitis and abscesses. Mental status changes are common. Seizures occur in at least 25% of patients.

- Gastroenteritis: L. monocytogenes can produce food-borne diarrheal disease, which typically is noninvasive. The median incubation period is 21 days, with diarrhea lasting anywhere from 1–3 days. Patients present with fever, muscle aches, gastrointestinal nausea or diarrhea, headache, stiff neck, confusion, loss of balance, or convulsions.

Particular strains of Listeria monocytogenes are able to invade the heart, leading to serious and difficult-to-treat heart infections. About 10 percent of serious listeria infections involve cardiac infections that are difficult to treat, with more than one-third proving fatal. A strain of listeria had been isolated from a patient with endocarditis (infection of the heart). Usually with endocarditis, there is bacterial growth on heart valves, but in this case the infection had invaded the cardiac muscle. When mice were infected with either the cardiac isolate or a lab strain, 10 times as much bacteria were found in the hearts of mice infected with the cardiac strain. In the spleen and liver, organs that are commonly targeted by listeria, the levels of bacteria were equal in both groups of mice. While the lab-strain-infected group often had no heart infection at all, 90 percent of the mice infected with the cardiac strain had heart infections. Only one other strain of listeria out of 10 acquired seemed to also target the heart. The results suggest that these two cardiac-associated strains display modified proteins on their surface that enable the bacteria to more easily enter cardiac cells, targeting the heart and leading to bacterial infection[12].

Recent outbreaks

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) there are about 1,600 cases of listeriosis annually in the United States. Compared to 1996-1998, the incidence of listeriosis had declined by about 38% by 2003. However, illnesses and deaths continue to occur. On average from 1998-2008, 2.4 outbreaks per year were reported to the CDC. A large outbreak occurred in 2002, when 54 illnesses, 8 deaths, and 3 fetal deaths in 9 states were found to be associated with consumption of contaminated turkey deli meat.[13]

The 2008 Canadian listeriosis outbreak, a widespread outbreak of listeriosis in Canada linked to a Maple Leaf Foods plant in Toronto, Ontario killed 23 people and there were 57 total confirmed cases.[14]

On September 14, 2011, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration warned consumers not to eat cantaloupes shipped by Jensen Farms from Granada, Colorado due to a potential link to a multi-state outbreak of listeriosis. At that time Jensen Farms voluntarily recalled cantaloupes shipped from July 29 through September 10, and distributed to at least 17 states with possible further distribution. The CDC reported that at least 22 people in seven states had been infected as of September 14.[15] On September 26, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that a total of 72 persons had been infected with the four outbreak-associated strains of Listeria monocytogenes which had been reported to the CDC from 18 states. All illnesses started on or after July 31, 2011 and by September 26, thirteen deaths had been reported: 2 in Colorado, 1 in Kansas, 1 in Maryland, 1 in Missouri, 1 in Nebraska, 4 in New Mexico, 1 in Oklahoma, and 2 in Texas.[16][17] On September 30, 2011, a random sample of romaine lettuce taken by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration tested positive for listeria on lettuce shipped on September 12 and 13 by an Oregon distributor to at least two other states -- Washington and Idaho.[18]

By October 18, the CDC reported that 12 states are now linked to listeria in cantaloupe and that 123 people have been sickened and a total of 25 have died. While the tainted cantaloupes should be off store shelves by now, the number of illnesses may still continue to grow. The CDC confirmed a sixth death in Colorado and a second in New York; Indiana, Kansas, Louisiana, Maryland, Missouri, Nebraska, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Texas and Wyoming have also reported deaths.[19]

See also

References

- ^ a b Ryan KJ; Ray CG (editors) (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). McGraw Hill. ISBN 0-8385-8529-9.

- ^ Hof H (1996). Listeria Monocytogenes in: Baron's Medical Microbiology (Baron S et al., eds.) (4th ed.). Univ of Texas Medical Branch. ISBN 0-9631172-1-1. (via NCBI Bookshelf).

- ^ a b University of Michigan Health System, Women's health advisor

- ^ "Listeriosis symptoms". CBC News. 27 August 2008. http://www.cbc.ca/health/story/2008/08/27/f-listeria-symptoms.html.

- ^ http://www.cdc.gov/listeria/outbreaks/cantaloupes-jensen-farms/092711/index.html

- ^ Swaminathan B, Gerner-Smidt P. 2007. The epidemiology of human listeriosis. Microbes In name="Mazza2002">Joseph Mazza (15 January 2002). Manual of clinical hematology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 127–. ISBN 9780781729802. http://books.google.com/?id=NzMKMPzbxZwC&pg=PA127. Retrieved 29 June 2010.

- ^ "CDC - Prevention - Listeriosis". CDC.gov. http://www.cdc.gov/listeria/prevention.html. Retrieved 2011-09-29.

- ^ Skinner et al. (1996). Listeria: the state of the science Rome 29–30 June 1995 Session IV: country and organizational postures on Listeria monocytogenes in food Listeria: UK government's approach. 7. Food control. pp. 245–247.

- ^ Health authorities link 12 deaths to contaminated meat

- ^ Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy, University of Minnesota –Listeriosis

- ^ Smittskyddsinstitutet –Statistik för listeriainfektion

- ^ Alonzo F, Bobo LD, Skiest DJ, Freitag NE (April 2011). "Evidence for subpopulations of Listeria monocytogenes with enhanced invasion of cardiac cells". J. Med. Microbiol. 60 (Pt 4): 423–34. doi:10.1099/jmm.0.027185-0. PMID 21266727.

- ^ http://www.cdc.gov/listeria/statistics.html

- ^ "Listeria monocytogenes outbreak". CFIA. 2009-03-12. http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/alert-alerte/listeria/listeria_2008-eng.php. Retrieved 2009-03-20.

- ^ http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm271899.htm

- ^ http://www.cdc.gov/listeria/outbreaks/index.html

- ^ http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-us-canada-15086103

- ^ http://abcnews.go.com/Health/listeria-found-lettuce/story?id=14641785

- ^ http://www2.timesdispatch.com/news/2011/oct/18/25-now-dead-listeria-outbreak-cantaloupe-ar-1392440/

External links

Firmicutes (low-G+C) Infectious diseases · Bacterial diseases: G+ (primarily A00–A79, 001–041, 080–109) Bacilli Streptococcusαoptochin susceptible: S. pneumoniae (Pneumococcal infection)optochin resistant: S. viridans: S. mitis, S. mutans, S. oralis, S. sanguinis, S. sobrinus, milleri groupβA, bacitracin susceptible: S. pyogenes (Scarlet fever, Erysipelas, Rheumatic fever, Streptococcal pharyngitis)B, bacitracin resistant, CAMP test+: S. agalactiaeungrouped: Streptococcus iniae (Cutaneous Streptococcus iniae infection)Listeria monocytogenes (Listeriosis)Clostridia Clostridium (spore-forming)Peptostreptococcus (non-spore forming)Peptostreptococcus magnusMollicutes MycoplasmataceaeUreaplasma urealyticum (Ureaplasma infection) · Mycoplasma genitalium · Mycoplasma pneumoniae (Mycoplasma pneumonia)Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae (Erysipeloid)Diseases of maternal transmission / perinatal infection / vertical transmission (P35–P39, 771) Gestational/

transplacental/TORCH complexvirus (Congenital rubella syndrome, Congenital cytomegalovirus infection, Neonatal herpes simplex) · Hepatitis B · Congenital varicella syndrome · HIV · Fifth diseasebacteria (Congenital syphilis)other (Toxoplasmosis)Transmissible at birth/

transcervicalCell-mediated immunodeficiency

of late pregnancyListeriosis · Congenital cytomegalovirus infectionBreastfeeding Categories:- Bacterial diseases

- Bacterium-related cutaneous conditions

- Listeriosis

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.