- Sodium cyclamate

-

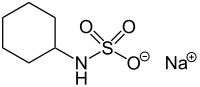

Sodium cyclamate  sodium N-cyclohexylsulfamate

sodium N-cyclohexylsulfamateIdentifiers PubChem 8751 ChemSpider 8421

ChEMBL CHEMBL273977 Jmol-3D images Image 1 - [Na+].O=S([O-])(=O)NC1CCCCC1

Properties Molecular formula C6H12NNaO3S Molar mass 201.22 g mol−1  (verify) (what is:

(verify) (what is:  /

/ ?)

?)

Except where noted otherwise, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C, 100 kPa)Infobox references Sodium cyclamate is an artificial sweetener. It is 30–50 times sweeter than sugar (depending on concentration; it is not a linear relationship), making it the least potent of the commercially used artificial sweeteners. Some people find it to have an unpleasant aftertaste, but, in general, less so than saccharin or acesulfame potassium. It is often used synergistically with other artificial sweeteners, especially saccharin; the mixture of 10 parts cyclamate to 1 part saccharin is common and masks the off-tastes of both sweeteners.[citation needed] It is less expensive than most sweeteners, including sucralose, and is stable under heating.

Contents

Chemistry

Cyclamate is the sodium or calcium salt of cyclamic acid (cyclohexanesulfamic acid), which itself is prepared by the sulfonation of cyclohexylamine. This can be accomplished by reacting cyclohexylamine with either sulfamic acid or sulfur trioxide.[citation needed]

History

Cyclamate was discovered in 1937 at the University of Illinois by graduate student Michael Sveda. Sveda was working in the lab on the synthesis of anti-fever medication. He put his cigarette down on the lab bench, and, when he put it back in his mouth, he discovered the sweet taste of cyclamate.[1]

The patent for cyclamate was purchased by DuPont but later sold to Abbott Laboratories, which undertook the necessary studies and submitted a New Drug Application in 1950. Abbott intended to use cyclamate to mask the bitterness of certain drugs such as antibiotics and pentobarbital. In the US in 1958, it was designated GRAS (Generally Recognized as Safe). Cyclamate was marketed in tablet form for use by diabetics as an alternative tabletop sweetener, as well as in a liquid form; one such product was named 'Sucaryl' and is still available in non-US markets.

Controversy developed when, in 1966, a study reported that some intestinal bacteria could desulfonate cyclamate to produce cyclohexylamine, a compound suspected to have some chronic toxicity in animals. Further research resulted in a 1969 study that found the common 10:1 cyclamate:saccharin mixture to increase the incidence of bladder cancer in rats. The released study was showing that eight out of 240 rats fed a mixture of saccharin and cyclamates, at levels of humans ingesting 350 cans of diet soda per day, developed bladder tumors. Other studies implicated cyclohexylamine in testicular atrophy in mice.[2] On October 18, 1969, the Food and Drug Administration banned its sale in the United States with citation of the Delaney Amendment after reports that large quantities of cyclamates could cause liver damage, bladder cancer, birth mutations and defects, reduce testosterone or shrivel the testes. In the same month, cyclamate was approved for use in the United Kingdom and is still used in low-calorie drinks; it is still available without restriction in the UK and Europe. As cyclamate is stable in heat, it was and is marketed as suitable for use in cooking and baking. Commercially, it is available as Sucaryl™. [3]

Abbott Laboratories claimed that its own studies were unable to reproduce the 1969 study's results, and, in 1973, Abbott petitioned the FDA to lift the ban on cyclamate. This petition was eventually denied in 1980 by FDA Commissioner Jere Goyan. Abbott Labs, together with the Calorie Control Council (a political lobby representing the diet foods industry), filed a second petition in 1982. Although the FDA has stated that a review of all available evidence does not implicate cyclamate as a carcinogen in mice or rats, cyclamate remains banned from food products in the United States. The petition is now held in abeyance, though not actively considered.[4] It is unclear whether this is at the request of Abbott Labs or because the petition is considered to be insufficient by the FDA.

Status

Cyclamate is approved as a sweetener in over 55 countries,[5] though it is banned in the United States. [6]

Sweeteners produced by Sweet'N Low and Sugar Twin[7] for Canada contain cyclamate, though not for those deployed in the United States.

Health

A 2003 "paper reports the first epidemiological study designed to investigate the possibility of a relationship between cyclamate and cyclohexylamine and male fertility in humans." It states that "the results demonstrate no effect of cyclamate or cyclohexylamine on male fertility at the present levels of cyclamate consumption."[8]

Incidences

In Taipei, Taiwan, a city health survey in 2010 found nearly 30% of tested dried fruit products failed a health standards test, most having excessive amounts of cyclamate, some at levels 20 times higher than the legal limit.[9]

In the Philippines, Magic Sugar, a brand of cyclamate, has been banned.[10] It was placed in coconut juices by local street-side vendors.

Brands

- Assugrin (Switzerland, Brazil)

- Sucaryl

- Sugar Twin (Canada)

- Chuker (Argentina) - Merisant Company 2, SARL

- Cologran

Notes and references

- ^ Packard, Vernal S. (1976). Processed foods and the consumer: additives, labeling, standards, and nutrition. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. pp. 332. ISBN 0-8166-0778-8.

- ^ "Potential side effects of Cyclamate". http://www.cspinet.org/reports/chemcuisine.htm#banned_additives.

- ^ "Worldwide Approval of Cyclamate". http://www.cyclamate.com/cyctable.html.

- ^ "Petitions Currently Held in Abeyance". http://www.fda.gov/Food/FoodIngredientsPackaging/FoodAdditives/ucm082418.htm.

- ^ http://www.cyclamate.com/cyctable.html

- ^ http://www.accessdata.fda.gov

- ^ "Tastes like sugar". http://www.sugartwin.com/index.cfm. Retrieved 1 November 2010.

- ^ Serra-Majem, L. Bassas, L. García-Glosas, R. Ribas, L. Inglés, C. Casals, I. Saavedram, P. Renwick, A. G. "Cyclamate intake and cyclohexylamine excretion are not related to male fertility in humans". http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14726272.

- ^ Jian Chen and Y.L. Kao (18 January 2010). "Nearly 30% dried, pickled foods fail safety inspections". The China Post. http://www.chinapost.com.tw/taiwan/national/national-news/2010/01/18/241326/Nearly-30.htm. Retrieved 1 November 2010.

- ^ http://www.chd11.doh.gov.ph/webfiles/pdf/pubadv/20060130-neotogen.pdf

External links

- Rosalindfranklin.edu

- European Commission Revised Opinion On Cyclamic Acid

- US FDA Petitions Currently Held in Abeyance

- List of other chemical and brand names for cyclamate

- A brief history of sweeteners, including the discovery of cyclamate

- Assugrin's website (French)

- concerns over potential "testicular wasting" in male users

E numbers - 950-969 Colours (E100–199) • Preservatives (E200–299) • Antioxidants & Acidity regulators (E300–399) • Thickeners, stabilisers & emulsifiers (E400–499) • pH regulators & anti-caking agents (E500–599) • Flavour enhancers (E600–699) • Antibiotics (E700–799) • Miscellaneous (E900–999) • Additional chemicals (E1100–1599)

Waxes (E900–909) • Synthetic glazes (E910–919) • Improving agents (E920–929) • Packaging gases (E930–949) • Sweeteners (E950–969) • Foaming agents (E990–999)

Acesulfame K (E950) • Aspartame (E951) • Cyclamate (E952) • Isomalt (E953) • Saccharin (E954) • Sucralose (E955) • Alitame (E956) • Thaumatin (E957) • Neohesperidin dihydrochalcone (E959) • Neotame (E961) • Aspartame-acesulfame salt (E962) • Maltitol (E965) • Lactitol (E966) • Xylitol (E967)

Categories:- Sweeteners

- Sulfamates

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.