- Criticism of Hinduism

-

This article is about social and cultural criticism of Hinduism. For bias and/or prejudice against Hindus, see anti-Hindu.Practices

Some aspects of practices committed by Hindus have been criticised, from both within the Hindu community and externally. Christian critics argue that Hindu philosophy and mythology is very complex and does not conform to normal Christian logic.[1] Overt depiction of sexuality in Hindu idols, imagery and rituals are also criticized.[2] Early Hindu reformers, such as Raja Ram Mohan Roy, questioned practices such as Sati and discrimination based on the caste system. However, caste based discrimination and self immolation are not endorsed by any of the Hindu scriptures, social practices evolved to them over time.[3][4][5][6][7][8] Manusmriti says that the varna system was innately non-hereditary.[9] Several critics allege that the stringent caste system was a by-product of the varna system that is mentioned in the ancient Hindu scriptures.[10]

Contents

Mythology

Concepts including reversal of salvation in which men try to save the gods, coming down of Gods to earth in order to expiate their sin and thus regain lifeblood, removing the impurity of death from themselves by Hindu gods, and giving it to the men were considered by critics as contradicting Christian mythology which they consider to be having a rational logic(Most of the critics were Christian).[1] New Larousse Encyclopedia of Mythology (1977) states: "Indian mythology is an inextricable jungle of luxuriant growths. When you enter it you lose the light of day and all clear sense of direction. In a brief exposition one cannot avoid over-simplification. But at least one can point out how, in the most favorable circumstances, paths may be traced leading to a methodical exploration of this vast domain"[11]

Sexuality

Wendy Doniger, has criticized Hindu ritual, including sexual, blood, and fringe elements in her book[2] "The Hindus: An Alternative History"[12] She says that several passages in rig-veda promotes immoral sexual activities. She alleges that in Rigveda 10.62, it is implied that a woman may find her own brother in her bed.[2] Her book mentions the Vedic devotee worshipping different Vedic deities to a lying and a philandering boyfriend cheating on his girlfriend.[13] In response, Doniger's criticisms are rejected by others, who see bias, poor scholarship, and prejudice in her work. Michael Witzel, a professor of Sanskrit at Harvard University, criticized Doniger's translations of the Rigveda as "unreliable and idiosyncratic".[14] Aditi Banerjee, Attorney and author of the book "Invading the Sacred" documents what she claims are numerous mistranslations and unjustified assumptions on the part of Doniger.[15] She also claims that Doniger is insufficiently skilled in Sanskrit to make reliable translations of the Rigveda, and that her criticisms and attacks on Hinduism are a rehash of Anti-Indian stereotypes promoted during the era of British colonialism.

Idol Worship

Western criticism of Hinduism as superstitious idolatry are based on the religious texts of Abrahamic religions which denounce and condemn the practice of creating Idols and Worshiping them. One of the passages in the Bible that criticize idol worship reads as follow.

Their idols are silver and gold, The work of the hands of earthling man. A mouth they have, but they cannot speak; Eyes they have, but they cannot see; Ears they have, but they cannot hear. A nose they have, but they cannot smell. Hands are theirs, but they cannot feel. Feet are theirs, but they cannot walk; They utter no sound with their throat. Those making them will become just like them, All those who are trusting in them.- Psalms 115:4-8

However many Hindu scholars have asserted that the notion about idol worship in Hinduism is misleading. They argue that the images, icons, and symbols, such as murtis are understood by Hindus themselves as being symbolic representations of various divine attributes of the Supreme Being, which is ultimately beyond all material names and forms.[16] Hindu reformist movements in the 18th - 19th centuries such as the Brahmo Samaj and Arya Samaj, were highly critical of image worship.[17] The 11 th century Persian scholar, Abū Rayḥān al-Bīrūnī, was the first non-Indian to analyze Hinduism in the context of idol worship while translating the works of Hindu cleric Patanjali from Sanskrit to Persian. He concluded:

The Hindus believe with regard to God that he is one, eternal, without begining and end, acting by free-will, almighty, all-wise, living, giving life, ruling, preserving; one who in his sovereignty is unique, beyond all likeness and unlikeness, and that he does not resemble anything nor does anything resemble.[18]

Medieval Persian geographer Ibn Khordadbeh classifies Hindus into three groups, those who are monotheist (man yuthbitu al-khaliq `azza wa jalla), those who reject the prophets of Islam (man yanfa al-rus´l); and those who do not believe in either monotheism or the Islamic prophets (wa minhum al-nafi li kulli dhalik)[19] However the use of icons in worship continues to be an issue of contention between Hindus and members of Abrahamic religions, whose scriptural texts often fulminate against idolatry.

Varna System

See also: Varna in HinduismThe Hindu system of varnas identified four varnas in Indian society.[20] The term varna is sometimes used synonymously with "caste" or "class"[21] The Sanskrit term for caste, in the sense of social categories, is jāti.[21][22] In historical Indic traditions the varna and caste systems are not the same system, although they are related.[23] The classical authors scarcely speak of anything other than the varnas. Indologists sometimes confuse the two.[24] Type(varna) obligations were a major concern of the Dharma Sutras and Dharma Shastras, where fulfillment of one's obligation (dharma) with regard to class (varna) and stage of life (ashrama) was a sign of brahmanical orthopraxy.[21] The four varnas are in descending hierarchical sequence: Brahmin, Kshatriya, Vaishya, and Shudra or the priests, warriors, business people and laborers. There was no varna like untouchable in Hinduism. The untouchables are considered a lower section of Shudra (Dalit) and was prevalent during the general deterioration of Indian society in middle age. The Varnabahya (outcast) is the one who never lived in cities and thus never became part of the Varna system. Many tribals (Adivasis) were Varnabahya. Varnabahya is not to be confused with untouchable. The varna system resulted in a great deal of social oppression and mistreatment of the lowest ranked castes, the Shudras (Dalits). As a result, Hinduism and the implementation of the caste system are often criticized for allowing oppression of people of lower castes, even though the original design of the caste system was not intended to harm or oppress.

Hindu religious literature, such as the Rig Veda, suggests that the original varna system was based on a flexible system, where people joined a varna and a related occupation based on their skills, qualities, and nature. However, over time, the varna system transformed into a rigid caste system, preventing the 'lower' classes (also called the 'backward castes') from rising. This caste system has gone beyond Hindus and includes Dalit or lower caste people in other religions like Islam, Christianity, Sikhism, etc. in India, Pakistan and other countries in the Indian subcontinent. Discrimination against classes began as a result of this rigid fixing of the caste system. Also, religious literature suggests that the inclusion of Dalits ('untouchables') outside of the caste system was a later addition, not part of the original system.

Untouchables used to live separately within a separate subcultural context of their own, outside the inhabited limits of villages and townships. No other castes would interfere with their social life since untouchables were lower in social ranking than even those of the shudra varna. As a result, Dalits were commonly banned from fully participating in Hindu religious life (they could not pray with the rest of the social classes or enter the religious establishments).

The inclusion of lower castes into the mainstream was argued for by Mahatma Gandhi who called them "Harijans" (people of God). The term Dalit is used now as the term Harijan is largely felt patronizing. As per Gandhi's wishes, reservation system with percentage quotas for admissions in universities and jobs has been in place for many lower castes since independence of India to bring them to the upper echelons of society. Dalit movements have been created to represent the views of Dalits and combat this traditional oppression. Caste-based discrimination is not unique to Hindus in India; converts to other religions and their descendants frequently preserve such social stratification.[25]

Caste System

See also: Caste system in IndiaThis is also the reason why shudras or the so called low caste people like Valmiki, Vyasa, Narada, Karna, Thiruvalluvar were raised to the position of a Brahmin or Kshatriya, in virtue or their superior learning or valour.[citation needed]

It was with the advent of the foreign invasions in India, that the caste system became rigid, and migration of people to different castes were stopped. Even then, enlightened masters from the lower castes such as Kabir, Ravi Das, Sri Narayana Guru were revered by the upper castes as well.[citation needed]

The most ancient scriptures—the Shruti texts, or Vedas, place very little importance on the caste system, mentioning caste only rarely and in a cursory manner. A hymn from the Rig Veda seems to indicate that one's caste is not necessarily determined by that of one's family:

I am a bard, my father is a physician, my mother's job is to grind the corn.—Rig Veda 9.112.3In the Vedic period, there also seems to no discrimination against the Shudras (which later became an ensemble of the so-called low-castes) on the issue of hearing the sacred words of the Vedas and fully participating in all religious rights, something which became totally banned in the later times.[26]

Some scholars believe that,[citation needed] in its initial period, the caste system was flexible and it was merit and job based. One could migrate from one caste to other caste by changing one's profession. This view is supported by records of sages who became Brahmins. For example, the sage Vishwamitra belonged to a Kshatriya caste, and only later became recognized as a great Brahmin sage, indicating that his caste was not determined by birth. Similarly, Valmiki, once a low-caste robber, became a great sage. Veda Vyasa, another sage, was the son of a fisherwoman.[27]

The Bhagavad Gita which is one of the many holy books of Hindus mentions that every living being has a soul which is a part of God and has several references against discrimination between not just humans but even animals. Chapter 5, verse 18 of Bhagawat Gita sums this up by saying that

"The enlightened and wise regards with equal mind a Brahmin endowed with learning and humility, an outcaste, a cow, an elephant, and even a dog".—Bhagawat Gita 5.18The system of four classes incorporated in Righteousness (Dharma) is meant to provide guidance with regard to behaviour and spiritual practice to be undertaken in accordance with qualifications, that is potential and requirement, so as to acquire Bliss.[28]

When India gained independence due to the efforts of Hindus like Gandhi, perfect equality was thrust upon the masses of India, no matter to what caste one belonged to, thus reestablishing and continuing the ancient tradition of India.

Untouchability was outlawed after India gained independence in 1947. It will take some time for the deadweight of tradition of the rigid caste system to be removed from India. But as enlightened Hinduism and Buddhism, as preached by Gandhi, Swami Vivekananda, Ramakrishna Paramahamsa, and others are reaching the masses, slowly these shackles are being dissolved.

Paramahansa Yogananda also opposed what he called to the un-Vedic caste system as we know it today. He taught that the caste system originated in a higher age, but became degraded through ignorance and self-interest. Yogananda said:

"These were (originally) symbolic designations of the stages of spiritual refinement. They were not intended as social categories. And they were not intended to be hereditary. Things changed as the yugas [cycles of time] descended toward mental darkness. People in the higher castes wanted to make sure their children were accepted as members of their own caste. Thus, ego-identification caused them to freeze the ancient classifications into what is called the ‘caste system.’ Such was not the original intention. In obvious fact, however, the offspring of a brahmin may be a sudra by nature. And a peasant, sometimes, is a real saint.”

—from Conversations with Yogananda, Crystal Clarity Publishers, 2003.

Status of women

Main article: Women in HinduismThe role of women in Hinduism is often disputed, and positions range from quite fair to intolerant. Hinduism is based on numerous texts, some of which date back to 2000 BCE or earlier. They are varied in authority, authenticity, content and theme, with the most authoritative being the Vedas. The position of women in Hinduism is widely dependent on the specific text and the context. Positive references are made to the ideal woman in texts such as the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. Women in vedic period were accorded very high status. The proof can be inferred from reference to thirty women seers contributing to Vedas.

Certain Hindu communities practice Matrilineality in which descent is traced through the female. The Nairs and some communities of Nambudiri Brahmins from Kerala as well as Bunts from Tulu Nadu, are matrilineal. In such communities, the woman is the family matriarch and has the right to inherit property, and having a female child is considered favorable for a family. The clan system is one in which a woman lives with her brothers and sisters, as well as her mother and cousins.

Several women sages and seers are mentioned in the Upanishads, the philosophical part of the Vedas, notable among them being Gargi and Maitreyi. The Sanskrit word for female teachers as Acharyā (as opposed to Acharya for teacher and Acharyini for teacher's wife) reveal that women were also given a place as Gurus.

The Harita Dharmasutra (of the Maitrayaniya school of Yayurveda) declares that there are two kind of women: Sadhyavadhu who marry, and the Brahmavaadini who are inclined to religion, they can wear the sacred thread, perform rituals like the agnihotra and read the Vedas. Bhavabhuti's Uttararamacharita 2.3 says that Atreyi went to Southern India where she studied the Vedas and Indian philosophy. Shankara debated with the female philosopher Ubhaya Bharati, and Madhava's Shankaradigvijaya (9.63) mentions that she was well versed in the Vedas. Tirukkoneri Dasyai (15th century) wrote a commentary on Nammalvar's Tiruvaayamoli, with reference to Vedic texts like the Taittiriya Yajurveda.

In the marriage hymn (RV 10.85.26), the wife "should address the assembly as a commander."[29] A Rig Veda hymn says "I am the banner and the head, a mighty arbitress am I: I am victorious, and my Lord shall be submissive to my will. (Rig Veda, Book 10. HYMN CLIX. Saci Paulomi). These are probably the earliest references to the position of women in Hindu society.

In modern times the Hindu wife has traditionally been regarded as someone who must at all costs remain chaste or pure.[30] This is in contrast with the very different traditions that have prevailed at earlier times in 'Hindu' kingdoms, which included highly respected professional courtesans (such as Amrapali of Vesali) sacred devadasis, mathematicians and female magicians (the basavis, the Tantric kulikas). Some European scholars observed in the nineteenth century Hindu women were "naturally chaste" and "more virtuous" than other women, although what exactly they meant by that is open to dispute. In any case, as male foreigners they would have been denied access to the secret and sacred spaces that women often inhabited.

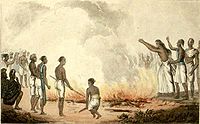

Sati

Main article: Sati (practice)Condemned practices like Sati (widow self-immolation or "bride burning") and widow remarriage were social practices that arose in India's Middle Ages, mostly in the northern regions of India, and had nothing to do with Hindu laws and scriptures. Whether Sati is a practice or a religious law is open for debate. For instance, Brahmin scholars of the second millennium justified the practice, and gave reasonings as to how the scriptures could be said to justify them. Among them were Vijnanesvara, of the Chalukya court, and later Madhavacharya, theologian and minister of the court of the Vijayanagara empire, according to Shastri, who quotes their reasoning. It was lauded by them as required conduct in righteous women, and it was explained that this was considered not to be suicide (suicide was otherwise variously banned or discouraged in the scriptures). It was deemed an act of peerless piety, and was said to purge the couple of all accumulated sin, guarantee their salvation and ensure their reunion in the afterlife. See main article on Sati in Wikipedia. In the later medieval ages, this practice came to be forced on the widows. However this practice was abolished from the society in the 20th century.

Sati was not prevalent in ancient history. In the epic Ramayana, King Dasharatha (Rama's father) left behind three widows who never committed Sati. In the same epic the wives of Vali Ravana and of other fallen warriors did not commit Sati after the deaths of their husbands. In the Mahabharata, Kunti, the mother of Pandavas (Yudhishtira, Arjuna, Bhima) and first wife of Pandu, was a widow who never committed Sati. However, Madri, second wife of Pandu and the mother of the younger pandavas (Nakula and Sahadeva) committed sati out of free-will and left her two sons in the care of Kunti. She was thinking herself responsible for her husband's death. Her husband, Pandu, had been cursed to die the day he lusts for his wife. Earlier in his life, while on a hunting expedition, he shot an arrow into a rustling bush. It turned out that he shot a pair of deer that were mating. The surviving deer morphed back into human form and revealed itself as a sage. The sage, deeply saddened by his loss and the brazen act of the king, curses him so. In the rest of the Mahabharata, there are no references to Kaurava wives committing Sati after their husbands died in Mahabharata war.

Passages in the Atharva Veda, including 13.3.1, offer advice to the widow on mourning and her life after widowhood, including her remarriage.

In the Ramayana, Tara, in her grief at the death of husband Vali, wished to commit sati. Hanuman, Rama, and the dying Vali dissuade her and she finally does not immolate herself.

During the Islamic conquests into the North-Western Indian Kingdoms, the Muslims had many concubines, who were the wives of the fallen warriors. It was to avoid the shame in being subjugated to being a whore in a Muslim Harem that many women decided to die faithful wives.[31] This was more of an act of suicide. As it has no validity in religious scriptures, it was only practiced in places where there was a dire need for the action. Rajasthan was one of the places where it was more common as due to its geographic position Rajasthan was one of the first regions to fight Muslim invaders coming to India. Practice of Jauhar in Rajasthan was also similar and had no basis in religious scriptures.

There is no record of Sati being practiced in the south Indian Hindu communities. Adi Shankaracharya's mother did not commit sati when her husband died.

Notes

- ^ a b Wendy Doniger O'Flaherty (1976). The Origins of Evil in Hindu Mythology. Berkeley: University of California. pp. 2–3,46,57,139.

- ^ a b c Wendy Doniger (2009). The Hindus: An Alternative History. penguin group. pp. 135, 252, 406.

- ^ Axel Michaels, Hinduism: Past and Present 188-97 (Princeton 2004) ISBN 0-691-08953-1

- ^ "Hindu Wisdom: The Caste System". http://www.hinduwisdom.info/Caste_System.htm. Retrieved 2006-12-08.

- ^ Nitin Mehta (2006-12-08). "Caste prejudice has nothing to do with the Hindu scriptures". The Guardian. http://www.guardian.co.uk/india/story/0,,1967446,00.html. Retrieved 2006-12-08.

- ^ M V Nadkarni (2003-11-08). "Is Caste System Intrinsic to Hinduism? Demolishing a Myth". Economic and Political Weekly. Archived from the original on 2007-03-12. http://web.archive.org/web/20070312101009/http://www.epw.org.in/showArticles.php?root=2003&leaf=11&filename=6474&filetype=html. Retrieved 2006-12-08.

- ^ "suttee." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2004 Encyclopædia Britannica Premium Service.

- ^ Euthanasia and Hinduism - ReligionFacts

- ^ ManuSmriti X:65: "As the son of Shudra can attain the rank of a Brahmin, the son of Brahmin can attain rank of a shudra. Even so with him who is born of a Vaishya or a Kshatriya".

- ^ David Haslam (2006-11-18). "Face to faith". The Guardian. http://www.guardian.co.uk/comment/story/0,,1951144,00.html. Retrieved 2006-12-08.

- ^ Robert Graves (1977). New Larousse Encyclopedia Of Mythology. Indian mythology: Hamlyn.

- ^ Top authors this week" Hindustan Times Indo-Asian News Service New Delhi, October 15, 2009

- ^ Wendy Doniger (2009). The Hindus: An Alternative History. penguin group. p. 128.

- ^ Mail from Witzel, subject "W.D.O'Flaherty's Rgveda "

- ^ Oh, But You Do Get It Wrong! Outlook - October 28, 2009

- ^ Bhagavad Gita, Chapters VIII through XII

- ^ Salmond, Noel Anthony (2004). "3. Dayananda Saraswati". Hindu iconoclasts: Rammohun Roy, Dayananda Sarasvati and nineteenth-century polemics against idolatry. Wilfrid Laurier Univ. Press. p. 65. ISBN 0889204195. http://books.google.com/?id=wxjArixq5hcC&printsec=frontcover&dq=Swami+Dayananda+Saraswati&cd=57#v=onepage&q=Swami%20Dayananda%20Saraswati&f=false.

- ^ Biruni and the study of non-Islamic Religions by Professor W. Montgomery Watt at [1].

- ^ e Ibn Khurdadhbih, Al-Masalik wa al-Mamalik (Damascus: Manshurat wa Zarat al-Thaqafah, 1999), 105. See also S. Maqbul Ahmad, Arabic Classical Accounts of India and China (Calcutta: Indian Institute of Advanced Studies, 1989), book 1, 7.

- ^ Keay, pp. 53-54.

- ^ a b c Flood, p. 58.

- ^ Apte, p. 451.

- ^ Mark Juergensmeyer, (2006) The Oxford Handbook of Global Religions (Oxford Handbooks in Religion and Theology), p. 54

- ^ Dumont, Louis (1980). Homo hierarchicus: the caste system and its implications. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 66–67. ISBN 0-226-16963-4

- ^ Ganguly, Rajat; Phadnis, Urmila (2001). Ethnicity and nation-building in South Asia. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. p. 88. ISBN 0-7619-9439-4.

- ^ White Yajurveda 26.2

- ^ Sabhlok, Prem. "Glimpses of Vedic Metaphysics". Page 21.

- ^ How did decline in righteousness cause creation of four classes?

- ^ R. C. Majumdar and A. D. Pusalker, editors, The History and Culture of the Indian People. Volume I: The Vedic age, (Bombay: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, 1951), p.424

- ^ Sarkar, Tanika (2001). Hindu Wife, Hindu Nation: Community, Religion and Cultural Nationalism. New Delhi: Permanent Black..[page needed]

- ^ Bhawan, Jain (1977). Jain journal, Volume 12. Jain Bhawan.. p. 76. http://books.google.com/?id=yb0nAQAAIAAJ&dq=hindu+women+suicide+India+muslim+avoid+shame&q=%22to+avoid+shame+and+dishonour.

References

- Apte, Vaman Shivram. The Practical Sanskrit-English Dictionary.

- Flood, Gavin (1996). An Introduction to Hinduism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-43878-0.

- Keay, John (2000). India: A History. Grove Press. ISBN 0-8021-3797-0.

Categories:- Hindu law

- Hinduism-related controversies

- Criticism of religion

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.