- Yoga Vasistha

-

Yoga Vasistha (Sanskrit: योग-वासिष्ठ) (also known as Vasistha's Yoga) is a Hindu spiritual text traditionally attributed to Valmiki. It recounts a discourse of the sage Vasistha to a young Prince Rama, during a period when the latter is in a dejected state. The contents of Vasistha's teaching to Rama is associated with Advaita Vedanta, the illusory nature of the manifest world[1] and the principle of non-duality. The book has been dated between the 11th and 14th century AD)[2] and is generally regarded as one of the longest texts in Sanskrit (after the Mahabharata) and an important text of Yoga. The book consists of about 32,000 shlokas (lines), including numerous short stories and anecdotes used to help illustrate its content. In terms of Hindu mythology, the conversation in the Yoga Vasishta takes place chronologically before the Ramayana.

Other names of this text are Mahā-Rāmāyana, ārsha Rāmāyana, Vasiṣṭha Rāmāyana,[3] Yogavasistha-Ramayana and Jnanavasistha.[1]

Contents

Text origin and evolution

See also: Buddhism and Hinduism in KashmirThe Yoga Vasistha is a syncretic work, containing elements of Vedanta, Jainism, Yoga, Samkhya, Saiva Siddhanta and Mahayana Buddhism.[4] The oldest available manuscript (the Moksopaya or Moksopaya Shastra) is a philosophical text on salvation (moksa-upaya: "means to release"), written on the Pradyumna hill in Srinagar in the 10th century AD.[5][6][7][8] This text was [2] expanded and Vedanticized from the 11th to the 14th century AD – resulting in the present text, which was influenced by the Saivite Trika school.[9] This version contains about 32,000 verses; an abridged version by Abhinanda of Kashmir (son of Jayanta Bhatta) is known as the Laghu ("Little") Yogavasistha and contains 6,000 verses.[10] Recent research has shown that in this version frame stories have been introduced, emphasis on Rama Bhakti has been added, the meaning of certain passages is reversed, all Buddhist terminology is deleted and the "public sermon" mode has been changed to Vasistha's instructions to Rama.[8]

Since 1999, the Moksopaya Project (supervised by professor Walter Slaje at the Martin Luther University of Halle-Wittenberg in Germany) has been working on a critical edition of the Moksopaya.[2][11]

Context

Prince Rama returns from touring the country, and becomes utterly disillusioned after experiencing the apparent reality of the world. This worries his father, King Dasaratha, who expresses his concern to Sage Vasistha upon Rama's arrival. Sage Vasistha consoles the king by telling him that Rama's dis-passion (vairagya) is a sign that the prince is now ready for spiritual enlightenment. He says that Rama has begun understanding profound spiritual truths, which is the cause of his confusion; he needs confirmation. Sage Vasistha asks the king to summon Rama. Then, in King Dasaratha's court, the sage begins his discourse to Rama (which lasts several days). The answer to Rama's questions forms the entire scripture that is Yoga Vasistha.

Content

The traditional belief is that reading this book leads to spiritual liberation. The conversation between Vasistha and Prince Rama is that between a great, enlightened sage and a seeker who is about to reach wholeness. This is said to be among those rare conversations which directly leads to Truth.

The scripture provides understanding, scientific ideas and philosophy; it explains consciousness, the creation of the world, the multiple universes in this world, our perception of the world, its ultimate dissolution, the liberation of the soul and the non-dual approach to creation.

An oft-repeated verse in the text is that relating to Kakathaliya, ("coincidence"). The story is that a crow alights on a palm tree, and that very moment the ripe palm fruit falls on the ground. The two events are apparently related, yet the crow never intended the palm fruit to fall; nor did the palm fruit fall because the crow sat on the tree. The intellect mistakes the two events as causally related, though in reality they are not.

Structure

Yoga Vasistha is divided into six parts: dis-passion, qualifications of the seeker, creation, existence, dissolution and liberation. It sums up the spiritual process in the seven Bhoomikas:

- Śubhecchā (longing for the Truth): The yogi (or sādhaka) rightly distinguishes between permanent and impermanent; cultivates dislike for worldly pleasures; acquires mastery over his physical and mental organism; and feels a deep yearning to be free from Saṃsāra.

- Vicāraṇa (right inquiry): The yogi has pondered over what he or she has read and heard, and has realized it in his or her life.

- Tanumānasa (attenuation – or thinning out – of mental activities): The mind abandons the many, and remains fixed on the One.

- Sattvāpatti (attainment of sattva, "reality"): The Yogi, at this stage, is called Brahmavid ("knower of Brahman"). In the previous four stages, the yogi is subject to sañcita, Prārabdha and Āgamī forms of karma. He or she has been practicing Samprajñāta Samādhi (contemplation), in which the consciousness of duality still exists.

- Asaṃsakti (unaffected by anything): The yogi (now called Brahmavidvara) performs his or her necessary duties, without a sense of involvement.

- Parārthabhāvanī (sees Brahman everywhere): External things do not appear to exist to the yogi (now called Brahmavidvarīyas), and tasks are performed only at the prompting of others. Sañcita and Āgamī karma are now destroyed; only a small amount of Prārabdha karma remains.

- Turīya (perpetual samādhi): The yogi is known as Brahmavidvariṣṭha and does not perform activities, either by his will or the promptings of others. The body drops off approximately three days after entering this stage.

Influence

Yoga Vasistha is considered one of the most important scriptures of the Vedantic philosophy.[12]

Commentaries

The following traditional Sanskrit commentaries on the Yoga Vasistha are extent

-

- Vāsiṣṭha-rāmāyaṇa-candrikā by Advayāraṇya (son of Narahari)

- Tātparya prakāśa by ānanda Bodhendra Sarasvatī

- Bhāṣya by Gaṅgādharendra

- Pada candrikā by Mādhava Sarasvatī

Translations

Originally written in Sanskrit, the Yoga Vasistha has been translated into most Indian languages, and the stories are told to children in various forms.[10]

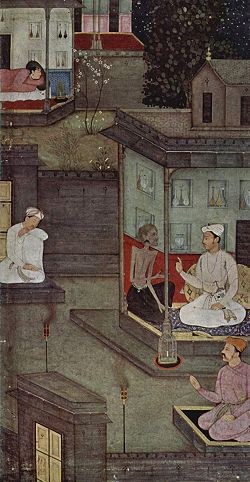

During the Moghul Dynasty the text was translated into Persian several times, as ordered by Akbar, Jahangir and Darah Shikuh.[1] One of these translations was undertaken by Nizam al-Din Panipati in the late sixteenth century AD. The translation, known as the Jug-Basisht, has since became popular in Persia among intellectuals interested in Indo-Persian culture.[13][14]

Yoga Vasistha was translated into English by Swami Jyotirmayananda, Swami Venkatesananda, Vidvan Bulusu Venkateswaraulu and Vihari Lal Mitra. K. Naryanaswami Aiyer translated the well-known abridged version, Laghu-Yoga-Vasistha. In 2009, Swami Tejomayananda's Yoga Vasistha Sara Sangrah was published by the Central Chinmaya Mission Trust. In this version the Laghu-Yoga-Vasistha has been condensed to 86 verses, arranged into seven chapters.

English translations

- 1) Complete translation

-

- Vālmīki (1891). The Yoga-Vásishtha-Mahárámáyana of Válmiki. trans. Vihārilāla Mitra. Calcutta: Bonnerjee and Co. pp. 3,650. OCLC 6953699.

- Vālmīki (1999). The Yoga-Vásishtha-Mahárámáyana of Válmiki. trans. Vihārilāla Mitra. Delhi: Low Price Publications.

- Vālmīki (2000). The Yoga-Vāsiṣṭha of Vālmīki. trans. Vihārilāla Mitra. Delhi: Parimal Publications. OCLC 53149153. Sanskrit text with English translation.

-

- This complete translation is currently being prepared for publication in the public domain at the Project Gutenberg/Distributed Proofreaders: http://www.pgdp.net. A preliminary version is available at:

- 2) Abbreviated versions

-

- Jyotirmayananda, Swami: Yoga Vasistha. Vol. 1–5. Yoga Research Foundation, Miami 1977. http://www.yrf.org

- Venkatesananda, Swami (1993). Vasiṣṭha's Yoga. Albany: State University of New York Press. pp. 768. ISBN 0585068011. OCLC 43475324. Abbreviated to about one-third of the original work.

- Venkatesananda, Swami (1984). The Concise Yoga Vāsiṣṭha. Albany: State University of New York Press. pp. 430. ISBN 0873959558. OCLC 11044869. http://books.google.com/books?id=1FFdOj2dv8cC. A shorter version of the above.

- Vālmīki (1896). Yoga-Vâsishta: Laghu, the Smaller. trans. K Nārāyaṇaswāmi Aiyar. Madras: Thompson and Co. p. 346 pages. OCLC 989105. http://www.archive.org/details/yogavasishtalagh00aiyeuoft.

- Abhinanda, Pandita (2003). The Yoga Vasishta (Abridged Version). trans. K.N. Subramanian. Chennai: Sura Books. p. 588 pages. http://books.google.com/books?id=tq9TSJGtemsC.

- Vālmīki (1930). Yoga Vashisht or Heaven Found. trans. Rishi Singh Gherwal. Santa Barbara, USA: Author. p. 185 pages. http://www.sacred-texts.com/hin/yvhf/index.htm.

Telugu translations

- Complete translation

-

- Vasishtha Rama Samvaadam, Sri Yeleswarapu Hanuma Ramakrishna. Vol. 1–4, Audio CD for Vol 1.

Excerpts

"The great remedy for the long-lasting disease of samsara is the enquiry, 'Who am I? To whom does this samsara belong?', which entirely cures it."

"Nothing whatsoever is born or dies anywhere at any time. It is Brahman alone, appearing in the form of the world."

"O Rama, there is no intellect, no consciousness, no mind and no individual soul (jiva). They are all imagined in Brahman."

"That consciousness which is the witness of the rise and fall of all beings – know that to be the immortal state of supreme bliss."

"Knowledge of truth, Lord, is the fire that burns up all hopes and desires as if they are dried blades of grass. That is what is known by the word samadhi – not simply remaining silent."

See also

Footnotes

- ^ a b c Leslie 2003, pp. 104

- ^ a b c Hanneder, Jürgen; Slaje, Walter. Moksopaya Project: Introduction.

- ^ Encyclopaedia of Indian Literature, Volume 5. pp. 4638, By various, Published by Sahitya Akademi, 1992, ISBN 81-260-1221-8, 9788126012213

- ^ Chapple 1984, pp. xii

- ^ Slaje, Walter. (2005). "Locating the Mokṣopāya", in: Hanneder, Jürgen (Ed.). The Mokṣopāya, Yogavāsiṣṭha and Related Texts Aachen: Shaker Verlag. (Indologica Halensis. Geisteskultur Indiens. 7). p. 35.

- ^ Gallery – The journey to the Pradyumnaśikhara

- ^ Leslie 2003, pp. 104–107

- ^ a b Lekh Raj Manjdadria. (2002?) The State of Research to date on the Yogavastha (Moksopaya).

- ^ Chapple 1984, pp. x–xi

- ^ a b Leslie 2003, pp. 105

- ^ Jürgen Hanneder. (2000). Notes on the Quality of the Text.

- ^ The Himalayan Masters: A Living Tradition, pp 37, By Pandit Rajmani Tigunait, Contributor Irene Petryszak, Edition: illustrated, revised, Published by Himalayan Institute Press, 2002, ISBN 0-89389-227-0, 9780893892272

- ^ Juan R.I. Cole in Iran and the surrounding world by Nikki R. Keddie, Rudolph P. Matthee, 2002, pp. 22–23

- ^ Baha'u'llah on Hinduism and Zoroastrianism: The Tablet to Mirza Abu'l-Fadl Concerning the Questions of Manakji Limji Hataria, Introduction and Translation by Juan R. I. Cole

References

- Chapple, Christopher; Venkatesananda, Swami (tr.) (1984). "Introduction". The Concise Yoga Vāsiṣṭha. Albany: State University of New York Press. ISBN 0873959558. OCLC 11044869. http://books.google.com/books?id=1FFdOj2dv8cC.

- Leslie, Julia (2003). Authority and meaning in Indian religions: Hinduism and the case of Vālmīki. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.. ISBN 0754634310. http://books.google.com/books?id=466QEN_Av4MC.

External links

- The Yoga-Vasistha of Valmiki with Vasistha Maharamayana - Tatparya Prakasa - The complete Sanskrit scripture in 2 parts, at archive.org

- http://www.hariomgroup.org/maharamayan

- http://sivaloka.tripod.com/YogaVasishtha.htm

- http://www.dlshq.org/religions/yogavasishtha.htm

- http://www.bhagwanvalmiki.com/yogvasistha1.htm

- An Index to the Yoga Vasistha

- Yoga Vasistha (narration by Gurugillies)

Indian philosophy Texts Vedas (includes the Mukhya Upanishads) · Upanishads (Whole list...) · Puranas: Vishnu Purana, Bhagavata Purana · Ramayana · Mahabharata · Bhagavad-Gita · Buddhist texts · Jain AgamasTopics Āstika Samkhya · Nyaya · Vaisheshika · Yoga · Mimamsa · Vedanta (Advaita · Vishishtadvaita · Dvaita · Acintya bheda abheda)Nāstika Cārvāka · Ājīvika · Jaina (Anekantavada · Syadvada) · Bauddha (Shunyata · Madhyamaka · Yogacara · Sautrantika · Svatantrika)Philosophical

TextsYoga Sutra | Nyaya Sutra | Vaiseshika Sutra | Samkhya Sutra | Mimamsa Sutra | Brahma Sutra | More...Philosophers Akshapada Gotama | Patanjali | Yajnavalkya | Kanada | Kapila | Jaimini | Vyasa | Nagarjuna | Madhvacharya | Kumarajiva | Padmasambhava | Vasubandhu | Adi Shankara | Ramanuja | More...Hinduism Categories:- Yoga texts and documentation

- Hindu texts

- Sanskrit texts

- Indian philosophy

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.