- Liberty

-

Part of a series on Freedom Concepts Rights

Free will

Moral responsibilityBy type Academic · Civil

Economic · Intellectual

Political · ScientificBy right Assembly · Association

Education · Information

Movement · Press

Religion · Speech (public)

Speech (schools) · ThoughtLiberty is a moral and political principle, or Right, that identifies the condition in which human beings are able to govern themselves, to behave according to their own free will, and take responsibility for their actions. There are different conceptions of liberty, which articulate the relationship of individuals to society in different ways, including some which relate to life under a "social contract" or to existence in a "state of nature", and some which see the active exercise of freedom and rights as essential to liberty.

Individualist and classical liberal conceptions of liberty typically consist of the freedom of individuals from outside compulsion or coercion, also known as negative liberty, while Social liberal conceptions of liberty emphasize social structure and agency, or positive liberty.

In feudal societies, a "liberty" was an area of allodial land in which the rights of the ruler, or monarch, had been waived.

Contents

Philosophy

Opinions on what constitute liberty can vary widely, but can be generally classified as positive liberty and negative liberty. Positive liberty asserts that freedom is found in a person's ability to exercise agency, particularly in the sense of having the power and resources to carry out their own will, without being inhibited by the structural inhibitions from society such as racism, classism or sexism. In the negative sense, one is considered free to the extent to which no person interferes with his or her activity. According to Thomas Hobbes, for example, "a free man is he that... is not hindered to do what he hath the will to do."

John Stuart Mill, in his work, On Liberty, was the first to recognize the difference between liberty as the freedom to act and liberty as the absence of coercion.[1] In his book, Two Concepts of Liberty, Isaiah Berlin formally framed the differences between these two perspectives as the distinction between two opposite concepts of liberty: positive liberty and negative liberty. The latter designates a negative condition in which an individual is protected from tyranny and the arbitrary exercise of authority, while the former refers to having the means or opportunity, rather than the lack of restraint, to do things.

Mill offered insight into the notions of soft tyranny and mutual liberty with his harm principle.[2] It can be seen as important to understand these concepts when discussing liberty since they all represent little pieces of the greater puzzle known as freedom. In a philosophical sense, it can be said that morality must supersede tyranny in any legitimate form of government. Otherwise, people are left with a societal system rooted in backwardness, disorder, and regression.

The concept of negative liberty has several noteworthy aspects. First, negative liberty defines a realm or "zone" of freedom (in the "silence of law"). In Berlin's words, "liberty in the negative sense involves an answer to the question 'What is the area within which the subject -- a person or group of persons -- is or should be left to do or be what he is able to do or be, without interference by other persons." Some philosophers have disagreed on the extent of this realm while accepting the main point that liberty defines that realm in which one may act unobstructed by others. Second, the restriction (on the freedom to act) implicit in negative liberty is imposed by a person or persons and not due to causes such as nature, lack, or incapacity. Helvetius expresses this point clearly: "The free man is the man who is not in irons, nor imprisoned in a gaol (jail), nor terrorized like a slave by the fear of punishment... it is not lack of freedom not to fly like an eagle or swim like a whale."

The dichotomy of positive and negative liberty is considered specious by political philosophers in traditions such as socialism, social democracy, libertarian socialism, and Marxism. Some of them argue that positive and negative liberty are indistinguishable in practice, while others claim that one kind of liberty cannot exist independently of the other. A common argument is that the preservation of negative liberty requires positive action on the part of the government or society to prevent some individuals from taking away the liberty of others.

A socialist, liberal and progressive defines liberty as being connected to the reasonably equitable distribution of wealth, arguing that the unrestrained concentration of wealth (the means of production) into only a few hands negates liberty. In other words, without relatively equal ownership, the subsequent concentration of power and influence into a small portion of the population inevitably results in the domination of the wealthy and the subjugation of the poor. Thus, freedom and material equality are seen as intrinsically connected. On the other hand, the classical liberal argues that wealth cannot be evenly distributed without force being used against individuals which reduces individual liberty.

Freedom as a triadic relation

In 1980, Gerald MacCallum argued that proponents of positive and negative liberty converge on a single definition of liberty, but simply have different approaches in establishing it. According to MacCallum, freedom is a triadic relationship: "x is/is not free from y to do/not to do or become/not become z". In this way, rather than defining liberty in terms of two separate paradigms, positive and negative liberty, he defined liberty as a single, complete formula.

The question is whether this formula fully captures what positive liberty means. Positive liberty, understood as "internal forces which determine how a person shall act"[3] is saying more than 'x is free to do z.' One is free when one becomes the ideal of oneself, which includes MacCallum's triadic relation; but the latter alone is insufficient to fully capture what positive liberty means.[citation needed]

Liberty and political thought

Concepts of liberty in history

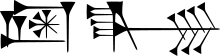

The first known use of the word freedom in a political context dates back to the 24th century BC, in a text describing the restoration of social and economic liberty in Lagash, a Sumerian city-state. Urukagina, the king of Lagash, established the first known legal code to protect citizens from the rich and powerful. Known as a great reformer, Urukagina established laws that forbade compelling the sale of property and required the charges against the accused to be stated before any man accused of a crime could be punished. This is the first known example of any form of due process in the history of humanity.

Like Urukagina, most ancient freedoms focused on negative liberty, protecting the less fortunate from harassment or imposition. Other ancient legal codes, such as the Code of Hammurabi, similarly forbade compulsion in economic matters, like the sale of land, and made it clear that when a rich man murders a poor one, it is still murder. Still, these codes depended on a certain virtuousness of kings and ministers, which was far from reliable.

The modern concept of liberty has its origins in the Greek concepts of freedom and slavery. To be free, to the Greeks, was to not have a master, to be independent from a master (to live like one likes).[4] That was the original Greek concept of freedom. It is closely linked with the concept of democracy, as Aristotle put it:

"This, then, is one note of liberty which all democrats affirm to be the principle of their state. Another is that a man should live as he likes. This, they say, is the privilege of a freeman, since, on the other hand, not to live as a man likes is the mark of a slave. This is the second characteristic of democracy, whence has arisen the claim of men to be ruled by none, if possible, or, if this is impossible, to rule and be ruled in turns; and so it contributes to the freedom based upon equality."[5]

So to the Greeks democracy was the system of government of a free society.

The populations of the Persian Empire enjoyed some degree of freedom. Citizens of all religions and ethnic groups were given the same rights and had the same freedom of religion, women had the same rights as men, and slavery was abolished.[when?] All the palaces of the kings of Persia were built by paid workers in an era where slaves typically did such work.[6]

In the Buddhist Maurya Empire of ancient India, citizens of all religions and ethnic groups had some rights to freedom, tolerance, and equality. The need for tolerance on an egalitarian basis can be found in the Edicts of Ashoka the Great, which emphasize the importance of tolerance in public policy by the government. The slaughter or capture of prisoners of war was also condemned by Ashoka.[7] Slavery was also non-existent in the Maurya Empire.[8] However, according to Hermann Kulke and Dietmar Rothermund, "Ashoka's orders seem to have been resisted right from the beginning."[9]

Roman law also embraced certain limited forms of liberty, even under the rule of the Roman Emperors. However, these liberties were accorded only to Roman citizens. Still, the Roman citizen enjoyed a combination of positive liberty (the right to a trial, a right of appeal, law and contract enforcement) and negative liberty (unhindered right to contract and the right to not be tortured). Many of the liberties enjoyed under Roman law endured through the Middle Ages, but were enjoyed solely by the nobility, never by the common man. The idea of unalienable and universal liberties had to wait until the Age of Enlightenment.

In Chinese, freedom is written 自由(ziyou). 自(zi) is the character for self, and 由(you) is the character to follow, with an additional connotation of reason. Liberty thus implies a necessary connection between individualism and a rational duty.

Social contract

In French Liberty. British Slavery (1792), James Gillray caricatured French "liberty" as the opportunity to starve, and British "slavery" as bloated complaints about taxation.

In French Liberty. British Slavery (1792), James Gillray caricatured French "liberty" as the opportunity to starve, and British "slavery" as bloated complaints about taxation.

The social contract theory, invented by Hobbes, John Locke and Rousseau, were among the first to provide a political classification of rights, in particular through the notion of sovereignty and of natural rights. The thinkers of the Enlightenment reasoned the assertion that law governed both heavenly and human affairs, and that law gave the king his power, rather than the king's power giving force to law. The divine right of kings was thus opposed to the sovereign's unchecked auctoritas. This conception of law would find its culmination in Montesquieu's thought. The conception of law as a relationship between individuals, rather than families, came to the fore, and with it the increasing focus on individual liberty as a fundamental reality, given by "Nature and Nature's God," which, in the ideal state, would be as expansive as possible. The Enlightenment created then, among other ideas, liberty: that is, of a free individual being most free within the context of a state which provides stability of the laws. Later, more radical philosophies such as socialism articulated themselves in the course of the French Revolution and in the 19th century.

Modern perspectives

The modern conceptions of democracy, whether representative democracies or other types of democracies, are all found on the Rousseauist idea of popular sovereignty.[original research?]

Liberalism is a political current embracing several historical and present-day ideologies that claim defense of individual liberty as the purpose of government. Two main strands are apparent, although both are founded on an individualist ideology. Economic liberalism is the right of the individual to contract, trade and operate in a market free of constraint. Social liberalism is the right to dissent from orthodox tenets or established authorities in political or religious matters. Both are core political issues, and highly contentious.[citation needed]

Article 3 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights states that "Everyone has the right to life, liberty, and security of person."

United States

In the United States Supreme Court decision Griswold v. Connecticut, Justice William O. Douglas argued that liberties relating to personal relationships, such as marriage, have a unique primacy of place in the hierarchy of freedoms.[10] Jacob M. Appel has summarized this principle:

I am grateful that I have rights in the proverbial public square—but, as a practical matter, my most cherished rights are those that I possess in my bedroom and hospital room and death chamber. Most people are far more concerned that they can control their own bodies than they are about petitioning Congress.[11]A school of thought popular among U.S. libertarians holds that there is no tenable distinction between the two sorts of liberty—that they are, indeed, one and the same, to be protected (or opposed) together. In the context of U.S. constitutional law, for example, they point out that the constitution twice lists "life, liberty, and property" without making any distinctions within that troika.

Anarcho-Individualists, such as Max Stirner, demanded the utmost respect for the liberty of the individual. Some in the U.S. see protecting the ideal of liberty as a conservative policy, because this would conform to the spirit of individual liberty that they consider is at the heart of the American constitution. Some think liberty is almost synonymous with democracy, at least in one sense of that word, while others see conflicts or even opposition between the two concepts, with democracy being nothing more than the tyranny of the majority.[citation needed]

Liberty Canon

See also

- Civil liberty

- Constitution

- Constitutional economics

- Freedom (philosophy)

- Freedom (political)

- Gratis versus Libre

- Libertarian Party

- Liberté, égalité, fraternité

- Rule according to higher law

- Social liberty

References

- ^ Westbrooks, Logan Hart (2008) "Personal Freedom" page 134 In Owens, William (compiler) (2008) Freedom: Keys to Freedom from Twenty-one National Leaders Main Street Publications, Memphis, Tennessee, pages 133-138, ISBN 978-0-9801152-0-8

- ^ John Stuart Mill, On Liberty and Utilitarianism, (New York: Bantam Books, 1993), 12-16.

- ^ Miller, David, 'Introduction', in Miller, ed., Liberty, 1991

- ^ Mogens Herman Hansen, 2010, Democratic Freedom and the Concept of Freedom in Plato and Aristotle

- ^ Aristotle, Politics

- ^ Arthur Henry Robertson, John Graham Merrills (1996). Human Rights in the World: An Introduction to the Study of the International Protection of Human Rights. Manchester University Press. ISBN 0719049237.

- ^ Amartya Sen (1997). Human Rights and Asian Values. ISBN 0-87641-151-0.

- ^ Arrian, Indica:

"This also is remarkable in India, that all Indians are free, and no Indian at all is a slave. In this the Indians agree with the Lacedaemonians. Yet the Lacedaemonians have Helots for slaves, who perform the duties of slaves; but the Indians have no slaves at all, much less is any Indian a slave." - ^ Hermann Kulke, Dietmar Rothermund (2004). "A history of India". Routledge. p.66. ISBN 0415329205

- ^ GRISWOLD v. CONNECTICUT U.S. Supreme Court 381 U.S. 479 (1965) Decided June 7, 1965

- ^ A Culture of Liberty

Articles of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights General principles Article 1: Freedom, Egalitarianism, Dignity and Brotherhood

Article 2: Universality of rightsInternational Covenant on Civil and Political Rights Article 1 and 2: Right to freedom from discrimination · Article 3: Right to life, liberty and security of person · Article 4: Freedom from slavery · Article 5: Freedom from torture and cruel and unusual punishment · Article 6: Right to personhood · Article 7: Equality before the law · Article 8: Right to effective remedy from the law · Article 9: Freedom from arbitrary arrest, detention and exile · Article 10: Right to a fair trial · Article 11.1: Presumption of innocence · Article 11.2: Prohibition of retrospective law · Article 12: Right to privacy · Article 13: Freedom of movement · Article 14: Right of asylum · Article 15: Right to a nationality · Article 16: Right to marriage and family life · Article 17: Right to property · Article 18: Freedom of thought, conscience and religion · Article 19: Freedom of opinion and expression · Article 20.1: Freedom of assembly · Article 20.2: Freedom of association · Article 21.1: Right to participation in government · Article 21.2: Right of equal access to public office · Article 21.3: Right to universal suffrage

International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights Article 1 and 2: Right to freedom from discrimination · Article 22: Right to social security · Article 23.1: Right to work · Article 23.2: Right to equal pay for equal work · Article 23.3: Right to just remuneration · Article 23.4: Right to join a trade union · Article 24: Right to rest and leisure · Article 25.1: Right to an adequate standard of living · Article 25.2: Right to special care and assistance for mothers and children · Article 26.1: Right to education · Article 26.2: Human rights education · Article 26.3: Right to choice of education · Article 27: Right to science and culture ·

Context, limitations and duties Article 28: Social order · Article 29.1: Social responsibility · Article 29.2: Limitations of human rights · Article 29.3: The supremacy of the purposes and principles of the United Nations

Article 30: Nothing in this Declaration may be interpreted as implying for any State, group or person any right to engage in any activity or to perform any act aimed at the destruction of any of the rights and freedoms set forth herein.Category:Human rights · Human rights portal Categories:- Political philosophy

- Social philosophy

- Liberty symbols

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.