- Petroleum politics

-

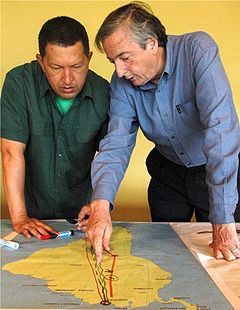

Argentine president Néstor Kirchner and Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez discuss the Gran Gasoducto del Suran energy and trade integration project for South America. They met on November 21, 2005 in Venezuela.

Argentine president Néstor Kirchner and Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez discuss the Gran Gasoducto del Suran energy and trade integration project for South America. They met on November 21, 2005 in Venezuela.

Petroleum politics have been an increasingly important aspect of diplomacy since the rise of the petroleum industry in the Middle East in the early 20th century. As competition grows for an increasingly scarce but vital resource, the strategic calculations of major and minor countries alike place more prominent emphasis on the pumping, refining, transport and use of petroleum products.

Contents

Quota agreements

The Achnacarry Agreement or "As-Is Agreement" was an early attempt to restrict petroleum production, signed in Scotland on 17 September 1928.[1] The discovery of the East Texas Oil Field in the 1930s led to a boom in production that caused prices to fall, leading the Railroad Commission of Texas to control production. The Commission retained de facto control of the market until the rise of OPEC in the 1970s.

The Anglo-American Petroleum Agreement of 1944 tried to extend these restrictions internationally but was opposed by the industry in the United States and so Franklin Roosevelt withdrew from the deal.

Venezuela was the first country to move towards the establishment of OPEC by approaching Iran, Gabon, Libya, Kuwait and Saudi Arabia in 1949, but OPEC was not set up until 1960, when the United States forced import quotas on Venezuelan and Persian Gulf oil in order to support the Canadian and Mexican oil industries[citation needed]. OPEC first wielded its power with the 1973 oil embargo against the United States and Western Europe.

Peak oil

In 1956, a Shell geophysicist named M. King Hubbert accurately predicted that U.S. oil production would peak in 1970.[2]

Matthew Simmons, an energy investment banker and a former adviser to US president George W. Bush believes that oil production in Saudi Arabia will soon peak, meaning it will not be able to supply the world's growing energy needs.

In June 2006, former U.S. president Bill Clinton said in a speech,[3]

"We may be at a point of peak oil production. You may see $100 a barrel oil in the next two or three years, but what still is driving this globalization is the idea that is you cannot possibly get rich, stay rich and get richer if you don’t release more greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. That was true in the industrial era; it is simply factually not true. What is true is that the old energy economy is well organized, financed and connected politically."

In a 1999 speech, Dick Cheney, the US Vice President and former CEO of Halliburton (one of the world's largest energy services corporations), said,

"By some estimates there will be an average of two per cent annual growth in global oil demand over the years ahead along with conservatively a three per cent natural decline in production from existing reserves. That means by 2010 we will need on the order of an additional fifty million barrels a day. So where is the oil going to come from?....While many regions of the world offer great oil opportunities, the Middle East with two thirds of the world's oil and the lowest cost, is still where the prize ultimately lies, even though companies are anxious for greater access there, progress continues to be slow."[4]

Cheney went on to argue that the oil industry should become more active in politics:

"Oil is the only large industry whose leverage has not been all that effective in the political arena. Textiles, electronics, agriculture all seem often to be more influential. Our constituency is not only oilmen from Louisiana and Texas, but software writers in Massachusetts and specialty steel producers in Pennsylvania. I am struck that this industry is so strong technically and financially yet not as politically successful or influential as are often smaller industries. We need to earn credibility to have our views heard."

Pipeline diplomacy in Caucasus

See also: Baku–Tbilisi–Ceyhan pipelineThe Baku–Tbilisi–Ceyhan pipeline was built to transport crude oil and the Baku-Tbilisi-Erzurum pipeline was built to transport natural gas from the western side (Azerbaijani sector) of the Caspian Sea to the Mediterranean Sea bypassing Russian pipelines and thus Russian control. Following the construction of the pipelines, the United States and the European Union proposed extending them by means of the proposed Trans-Caspian Oil Pipeline and the Trans-Caspian Gas Pipeline under the Caspian Sea to oil and gas fields on the eastern side (Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan sectors) of the Caspian Sea. In 2007, Russia signed agreements with Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan to connect their oil and gas fields to the Russian pipeline system effectively killing the undersea route.

China has completed the Kazakhstan–China oil pipeline from the Kazakhstan oil fields to the Chinese Alashankou-Dushanzi Crude Oil Pipeline in China. China is also working on the Kazakhstan-China gas pipeline from the Kazakhstan gas fields to the Chinese West-East Gas Pipeline in China.

Petroleum politics

Iran

Discovery of oil in 1908 at Masjed Soleiman in Iran initiated the quest for oil in the Middle East. The Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (AIOC) was founded in 1909. In 1951, Iran nationalized its oil fields initiating the Abadan Crisis. The United States of America and Great Britain thus punished Iran by arranging coup against its democratically elected prime minister, Mosaddeq, and brought the former Shah's son, a dictator, to power. In 1953 the US and GB arranged the arrest of the Prime Minister Mosaddeq. Iran exports oil to China and Russia. See also: Iranian Oil Subsidies

Iraq

Iraq holds the world's second-largest proven oil reserves, with increasing exploration expected to enlarge them beyond 200 billion barrels (3.2×1010 m3) of "high-grade crude, extraordinarily cheap to produce."[5] Organizations such as the Global Policy Forum (GPF) have asserted that Iraq's oil is "the central feature of the political landscape" there, and that as a result of the 2003 invasion,"'friendly' companies expect to gain most of the lucrative oil deals that will be worth hundreds of billions of dollars in profits in the coming decades." According to GPF, U.S. influence over the 2005 Constitution of Iraq has made sure it "contains language that guarantees a major role for foreign companies."[6][7]

Nigeria

Petroleum in Nigeria was discovered in 1955 at Oloibiri in the Niger Delta.[8]

High oil prices were the driving force behind Nigeria’s economic growth in 2005. The country’s real gross domestic product (GDP) grew approximately 4.5 percent in 2005 and was expected to grow by 6.2 percent in 2006. The Nigerian economy is heavily dependent on the oil sector, which accounts for 95 percent of government revenues. Even with the substantial oil wealth, Nigeria ranks as one of the poorest countries in the world, with a $1,000 per capita income and more than 70 percent of the population living in poverty. In October 2005, the 15-member Paris Club announced that it would cancel 60 percent of the debt owed by Nigeria. However, Nigeria must still pay $12.4 billion in arrears amongst meeting other conditions. In March 2006, phase two of the Paris Club agreement will include an additional 34 percent debt cancellation, while Nigeria will be responsible for paying back any remaining eligible debts to the lending nations. The International Monetary Fund (IMF), which recently praised the Nigerian government for adopting tighter fiscal policies, will be allowed to monitor Nigeria without having to disburse loans to the country.[9]

Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia is an oil-based economy with strong government controls over major economic activities. It possesses both the world's largest known oil reserves, which are 25% of the world's proven reserves, and produces the largest amount of the world's oil. As of 2005, Ghawar field accounts for about half of Saudi Arabia's total oil production capacity.[10]

Saudi Arabia ranks as the largest exporter of petroleum, and plays a leading role in OPEC, its decisions to raise or cut production almost immediately impact world oil prices.[11] It is perhaps the best example of a contemporary energy superpower, in terms of having power and influence on the global stage (due to its energy reserves and production of not just oil, but natural gas as well). Saudi Arabia is often referred to as the world's only "oil superpower".[12]

United States

In 1998, about 40% of the energy consumed by the United States came from Oil.[13] The United States, with about 5% of the world's population, is responsible for 25% of the world's oil consumption while only having 3% of the world's proven oil reserves.[14] As of 2004, the U.S. had 21 billion barrels (3.3×109 m3) of proven oil reserves and consumes 20.6 million bpd.

Venezuela

According to the Oil and Gas Journal (OGJ), Venezuela has 77.2 billion barrels (1.227×1010 m3) of proven conventional oil reserves, the largest of any country in the Western Hemisphere. In addition it has non-conventional oil deposits similar in size to Canada's - at 1,200 billion barrels (1.9×1011 m3) approximately equal to the world's reserves of conventional oil. About 267 billion barrels (4.24×1010 m3) of this may be producible at current prices using current technology.[15] Venezuela's Orinoco tar sands are less viscous than Canada's Athabasca oil sands – meaning they can be produced by more conventional means, but are buried deeper – meaning they cannot be extracted by surface mining. In an attempt to have these extra heavy oil reserves recognized by the international community, Venezuela has moved to add them to its conventional reserves to give nearly 350 billion barrels (5.6×1010 m3) of total oil reserves. This would give it the largest oil reserves in the world, even ahead of Saudi Arabia.

Venezuela nationalized its oil industry in 1975-1976, creating Petróleos de Venezuela S.A. (PdVSA), the country's state-run oil and natural gas company. Along with being Venezuela's largest employer, PdVSA accounts for about one-third of the country’s GDP, 50 percent of the government’s revenue and 80 percent of Venezuela’s exports earnings. In recent years, under the influence of President Chavez, the Venezuelan government has reduced PdVSA’s previous autonomy and amended the rules regulating the country’s hydrocarbons sector.[16]

In the 1990s, Venezuela opened its upstream oil sector to private investment. This collection of policies, called apertura, facilitated the creation of 32 operating service agreements (OSA) with 22 separate foreign oil companies, including international oil majors like Chevron, BP, Total, and Repsol-YPF.

Estimates of Venezuelan oil production vary. Venezuela claims its oil production is over 3 million barrels per day (480,000 m3/d), but oil industry analysts and the U.S. Energy Information Administration believe it to be much lower. In addition to other reporting irregularities[citation needed], much of its production is extra-heavy oil, which may or may not be included with conventional oil in the various production estimates. The U.S. Energy Information Agency estimated Venezuela's oil production in December 2006 was only 2.5 million barrels per day (400,000 m3/d), a 24% decline from its peak of 3.3 million in 1997.[17]

Hugo Chávez, the President of Venezuela sharply diverged from previous administrations' economic policies, terminating their practice of extensively privatizing Venezuela's state-owned holdings, such as the oil sector.[18] Chávez also worked to reduce Venezuelan oil extraction in the hopes of garnering elevated oil prices and, at least theoretically, elevated total oil revenues, thereby boosting Venezuela's severely deflated foreign exchange reserves. He extensively lobbied other OPEC countries to cut their production rates as well. As a result of these actions, Chávez became known as a "price hawk" in his dealings with the oil industry and OPEC. Chávez also attempted a comprehensive renegotiation of 60-year-old royalty payment agreements with oil giants Philips Petroleum and ExxonMobil.[19] These agreements had allowed the corporations to pay in taxes as little as 1% of the tens of billions of dollars in revenues they were earning from the Venezuelan oil they were extracting. Afterwards, a frustrated Chávez stated his intention to complete the nationalization of Venezuela's oil resources. Although unsuccessful in his attempts to renegotiate with the oil corporations, Chávez succeeded in improving both the fairness and efficiency of Venezuela's formerly lax tax collection and auditing system, especially for major corporations and landholders.

Recently, Venezuela has pushed the creation of regional oil initiatives for the Caribbean (Petrocaribe), the Andean region (Petroandino), and South America (Petrosur), and Latin America (Petroamerica). The initiatives include assistance for oil developments, investments in refining capacity, and preferential oil pricing. The most developed of these three is the Petrocaribe initiative, with 13 nations signing a preliminary agreement in 2005. Under Petrocaribe, Venezuela will offer crude oil and petroleum products to Caribbean nations under preferential terms and prices, with Jamaica as the first nation to sign on in August 2005.

Politics of Oil Nationalization

The politics of oil nationalization has involved Western governments using coups and covert actions to prevent foreign regimes from taking control of Western run oil companies in these respective countries. Enrique Mosconi, the director of the Argentine state owned oil company Yacimientos Petrolíferos Fiscales (YPF, which was the first state owned oil company in the world, preceding the French Compagnie française des pétroles (CFP, French Company of Petroleums), created in 1924 by the conservative Raymond Poincaré), advocated oil nationalization in the late 1920s among Latin American countries. The latter was achieved in Mexico during Lázaro Cárdenas's rule, with the Expropiación petrolera.

Iran and Venezuela are two important examples of foreign interventions to upset nationalization projects. In 1953, Iran's Premier Mohammed Mossadegh was overthrown by a CIA/MI6 covert action known as Operation Ajax. The goal was to prevent Mossadegh from nationalizing the Anglo-Iranian oil company which later became British Petroleum. Similarly in Venezuela, Hugo Chavez attempted to nationalize Venezuela's oil during the early years of his presidency. Hugo Chavez rapidly reversed policy after a 2002 failed coup following a strike and heavy protests concerning his policies towards PDVSA. This coup was backed by the governments of the United States and Spain, as is documented in Tariq Ali's book, Pirates of the Caribbean.

Politics of alternative fuels

Vinod Khosla (a well known investor in IT firms and alternative energy) argues[20] that the political interests of environmental advocates, agricultural businesses, energy security advocates (such as ex-CIA director James Woolsey) and automakers, are all aligned for the increased production of ethanol. He pointed out that from 2003 to 2006, ethanol fuel in Brazil has replaced 40% of its gasoline consumption while flex fuel vehicles went from 3% of car sales to 70%. Brazilian ethanol, which is produced using sugarcane, reduces green house gases by 60-80% (20% for corn produced ethanol). Khosla also says that ethanol is about 10% cheaper per given distance. There are currently ethanol subsidies in the United States but they are all blender's credits, meaning the oil refineries receive the subsidies rather than the farmers. There are indirect subsidies due to subsidising farmers to produce corn. Vinod says after one of his presentations in Davos, a Senior Saudi oil official came up to him and threatened: “If biofuels start to take off we will drop the price of oil.”[21] Since then, Vinod has come up with a new recommendation that oil should be taxed if it drops below $40.00/barrel in order to counter price manipulation.

Ex-CIA director James Woolsey and U.S. Senator Richard Lugar are also vocal proponents of ethanol.[22]

In 2005, Sweden announced plans to end its dependence on fossil fuels by the year 2020.[23]

See also

- Chronology of world oil market events (1970-2005)

- Energy superpower

- Geostrategy in Central Asia

- KAZENERGY Eurasian Forum

- New Great Game

- Oil reserves

- Oil Shockwave

- Petrodollar Warfare

- Shanghai Cooperation Organisation

- The Great Game

References

- ^ Bamberg, J.H. (1994). The History of the British Petroleum Company, Volume 2: The Anglo-Iranian Years, 1928-1954. Cambridge University Press. pp. 528–34. http://www.mtholyoke.edu/acad/intrel/energy/achnacarry.htm. Text of the 18 August 1928 draft of the Achnacarry Agreement.

- ^ Vidal, John (21 April 2005). "The end of oil is closer than you think". The Guardian (London). http://www.guardian.co.uk/life/feature/story/0,13026,1464050,00.html. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- ^ Clinton, Bill (March 28, 2006). "Speech at the London Business School". Energy Bulletin. http://www.energybulletin.net/node/15300. Retrieved 2008-11-23.

- ^ Institute of Petroleum - Dick Cheney's Autumn lunch speech

- ^ Global Policy Forum: Oil in Iraq retrieved 26 July 2007

- ^ Global Policy Forum: Oil in Iraq retrieved 26 July 2007]

- ^ "Crude Designs." Greg Muttitt, Global Policy Forum, November 2005

- ^ An MBendi Profile: Nigeria - Oil and Gas: Crude Petroleum and Natural Gas Extraction - Overview

- ^ Nigeria Energy Data, Statistics and Analysis - Oil, Gas, Electricity, Coal

- ^ http://www.eia.doe.gov/emeu/cabs/saudi.html

- ^ CIA - The World Factbook - Saudi Arabia

- ^ Saudi vows to keep oil flowing, by CNN 31 May 2004

- ^ U S Energy and World Energy Statistics

- ^ NRDC: Reducing U.S. Oil Dependence

- ^ [1]

- ^ http://www.eia.doe.gov/emeu/cabs/Venezuela/Oil.html

- ^ EIA - International Energy Data and Analysis

- ^ Venezuela’s “Demonstration Effect”: Defying Globalization’s Logic | venezuelanalysis.com

- ^ Hugo Chavez Frias

- ^ Biofuels: Think Outside The Barrel

- ^ "A healthier addiction". The Economist. 23 March 2006. http://www.economist.com/people/displaystory.cfm?story_id=5655161.

- ^ www.senate.gov - This page cannot be found

- ^ [2][dead link]

Further reading

- Aburish, Said K. The Rise, Corruption and Coming Fall of the House of Saud. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1994.

- Adelman, Morris A. The World Petroleum Market. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1972.

- _____. The Genie Out of the Bottle: World Oil Since 1970. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1995.

- Ahmad Khan, Sarah. Nigeria : The Political Economy of Oil. New York : Oxford University Press for the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, 1994.

- Ahrari, Mohammed E. OPEC: The Failing Giant. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1986.

- Allen, Loring. OPEC Oil. Cambridge, Mass.: Oelgeschlager, Gunn and Hain, 1979.

- Alnasrawi, Abbas. “Collective Bargaining Power in OPEC.’’ Journal of World Trade Law 7 (March-April 1973): 188–207.

- ———. Arab Nationalism, Oil, and the Political Economy of Dependency. New York: Greenwood Press, 1991.

- ———. The Economy of Iraq: Oil, Wars, Destruction of Development and Prospects, 1950–2010. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1994.

- Amuzegar, Jahangir, Managing the Oil Wealth: OPEC’s Windfalls and Pitfalls, London/New York: I.B. Tauris Publishers, 1999.

- _____. “OPEC as Omen: A Warning to the Caspian,” Foreign Affairs 77 (November/December 1998): 95-112.

- Barnes, Philip, Indonesia: The Political Economy of Energy. New York : Oxford University Press for the Oxford Institute of Energy Studies, 1995.

- Blair, John M. The Control of Oil. New York: Pantheon, 1976.

- Boué, Juan Carlos. Venezuela: The Political Economy of Oil. New York: Oxford University Press for the Oxford Institute of Energy Studies, 1993.

- Bromley, Simon. American Hegemony and World Oil: The Industry, the State System, and the World Economy. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1991.

- Brown, Anthony Cave. Oil, God, and Gold. New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1999.

- Cowhey, Peter F. The Problems of Plenty: Energy Policy and International Politics. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985.

- Crystal, Jill. Oil and Politics in the Gulf: Rules and Merchants in Kuwait and Qatar. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

- Danielsen, Albert L. The Evolution of OPEC. New York: Harcourt Brace Jonanovich, 1982.

- Deagle, Edwin A., Jr. The Future of the International Oil Market. New York: Group of Thirty, 1983.

- Eckbo, Paul Leo. The Future of World Oil. Cambridge, Mass.: Ballinger, 1976.

- Elm, Mostafa. Oil, Power, and Principle: Iran’s Oil Nationalization and Its Aftermath. Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press, 1992.

- Engler, Robert. The Politics of Oil: Private Power and Democratic Directions. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1961.

- ———. The Brotherhood of Oil: Energy Policy and the Public Interest. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1977.

- Fossum, John Erik. Oil, the State, and Federalism: The Rise and Demise of Petro-Canada as a Statist Impulse. Toronto; Buffalo : University of Toronto Press, 1997.

- Freedman, Lawrence, and Efraim Karsh. The Gulf Conflict 1990–1991: Diplomacy and War in the New World Order. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993.

- Fried, Edward R. and Philip H. Trezise. Oil Security: Retrospect and Prospect. Washington: Brookings Institution, 1993.

- Fursenko, A. A. The Battle for Oil: The Economics and Politics of International Corporate Conflict over Petroleum, 1860–1930. Greenwich, Conn.: Jai Press, 1990.

- Gause, F. Gregory, III. Oil Monarchies: Domestic and Security Challenges in the Arab Gulf States. New York: Council on Foreign Relations Press, 1993.

- Geller, Howard, et al., “Twenty years after the embargo: U.S. oil import dependence and how it can be reduced,” Washington: American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy, 1993

- Ghadar, Fariborz. The Evolution of OPEC Strategy. Lexington, Mass.: Lexington Books, 1977.

- Ghanem, Shukri. OPEC: The Rise and Fall of an Exclusive Club. London, New York and Sidney: KPI, 1986.

- Gilbar, Gad G., The Middle East Oil Decade and Beyond: Essays in Political Economy, London; Portland, Oregon: Frank Cass, 1997.

- Giusti, Luis E., “La Apertura: The Opening of Venezuela's Oil Industry,” Journal of International Affairs, 53, Fall, 1999

- Goldman, Marshall I., “Russian Energy; A Blessing and a Curse,” Journal of International Affairs, 53, Fall, 1999

- Griffin, James M., and David J. Teece. OPEC Behavior and World Oil Prices. London: George Allen and Unwin, 1982

- Gurney, Judith, Libya, the political economy of energy, Oxford; New York : Oxford University Press for the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, 1996

- Hallwood, C. Paul. Transaction Costs and Trade Between Multinational Corporations: A Study of Offshore Oil Production. Boston: Unwin Hyman, 1990.

- Hartshorn, J. E. Oil Companies and Governments: An Account of the International Oil Industry in Its Political Environment, 2nd rev. ed. London: Faber, 1967.

- ———. Oil Trade: Politics and Prospects. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

- Heal, Geoffrey M., and Graciela Chichilnisky. Oil and the International Economy. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1991.

- Heradstveit, Daniel, and Helge Hveem. Oil in the Gulf: Obstacles to Democracy and Development. : Ashgate, 2004.

- Ikein, Augustine A. and Comfort Briggs-Anigboh, Oil and fiscal federalism in Nigeria: the political economy of resource allocation in a developing country, Aldershot, England: Ashgate, 1998

- Ikenberry, G. John. Reasons of State: Oil Politics and the Capacities of American Government. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1988.

- Jayazeri, Ahmad. Economic Adjustment in Oil-Based Economies. Aldershot: Avebury, 1988.

- Jentleson, Bruce W. Pipeline Politics: The Complex Political Economy of East-West Energy Trade. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1986.

- ———. With Friends Like These: Reagan, Bush, and Saddam 1982–1990. New York: Norton, 1994.

- Karl, Terry Lynn, “The Perils of the Petro-State: Reflections on the Paradox of Plenty, Journal of International Affairs 53 (fall 1999):

- Karl, Terry Lynn. The Paradox of Plenty: Oil Booms and Petro-States. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997.

- _____. “The Perils of the Petro-State: Reflections on the Paradox of Plenty,” Journal of International Affairs 53 (fall 1999): 31-48.

- Kelly, J. B. Arabia, the Gulf, and the West: A Critical View of the Arabs and Their Oil Policy. New York: Basic Books, 1980.

- Klapp, Merrie Gilbert. The Sovereign Entrepreneur: Oil Policies in Advanced and Less Developed Capitalist Countries. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1987.

- Kohl, Wilfrid L. ed., After the Oil Price Collapse: OPEC, the United States, and the World Oil Market, Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991

- Kolawole, Dipo and N. Oluwafemi Mimiko, eds., Political Democratisation and Economic De-regulation in Nigeria under the Abacha Administration 1993-1998. Ado-Ekiti, Nigeria: Dept. of Political Science, Ondo State University, 1998.

- Krasner, Stephen D. Defending the National Interest: Raw Materials Investments and U.S. Foreign Policy. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1978.

- ———. “Oil Is the Exception.’’ Foreign Policy 14 (spring 1974): 68–90.

- Lane, David Stuart ed., The Political Economy of Russian Oil. Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield, 1999.

- Mattione, Richard. OPEC’s Investments and the International Financial System. Washington: Brookings Institution, 1985.

- Mazarei, Adnan, “The parallel market for foreign exchange in an oil exporting economy : the case of Iran, 1978-1990,” Washington: International Monetary Fund, Middle Eastern Dept., 1995

- Mikdashi, Zuhayr. A Financial Analysis of Middle Eastern Oil Concessions: 1901–1965. New York: Praeger, 1966.

- ———. The Community of Oil Exporting Countries: A Study in Governmental Cooperation. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1972.

- Mofid, K. The Economic Consequences of the Gulf War. London: Routledge, 1990.

- Morse, Edward L. “The Coming Oil Revolution.” Foreign Affairs 68 (winter 1990)

- _____. “A New Political Economy of Oil?” Journal of International Affairs 53 (fall 1999): 1-29.

- Noreng, Oystein. Oil Politics in the 1980s: Patterns of International Cooperation. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1978.

- ———. The Pressures of Oil: A Strategy for Economic Revival. New York: Harper and Row, 1978.

- Nowell, Gregory P., Mercantile States and the World Oil Cartel, 1900–1939, Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1994

- Odell, Peter R. An Economic Geography of Oil. New York; Praeger, 1963.

- ———. Oil and World Power: Background to the Oil Crisis. Harmondsworth, England: Penguin, 1974.

- ———, and Luis Vallenilla. The Pressures of Oil. London: Harper and Row, 1978.

- Okowa, W. J., et al., Oil, systemic corruption, Abdulistic capitalism and Nigerian development policy: a political economy, Port Harcourt <Nigeria>: Pam Unique Publishers, 1994

- Pearce, Joan, ed. The Third Oil Shock: The Effects of Lower Oil Prices. London: Royal Institute of International Affairs, 1983.

- Penrose, Edith T. The Large International Firm in Developing Countries: The International Petroleum Industry. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1969.

- Philip, George D. E. The Political Economy of International Oil. Edinburgh, Scotland: Edinburgh University Press, 1994.

- Randall, Laura, The Political Economy of Brazilian Oil. Westport, Conn.: Praeger, 1993.

- Rauscher, Michael. OPEC and the Price of Petroleum: Theoretical Considerations and Empirical Evidence. New York: Springer, 1989.

- Robinson, Jeffrey. Yamani: The Inside Story. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 1989.

- Rosenberg, Christoph B. and Tapio O. Saavalainen, How to deal with Azerbaijan's oil boom?: policy strategies in a resource-rich transition economy. Washington: International Monetary Fund, European II Dept., c1998.

- Rouhani, Fuad. A History of OPEC. New York: Praeger, 1971.

- Rustow, Dankwart A., and John F. Mungo. OPEC, Success and Prospects. New York: New York University Press, 1976.

- Sampson, Anthony. The Seven Sisters: The Great Oil Companies and the World They Made. New York: Viking, 1975.

- Schneider, Steven A. The Oil Price Revolution. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1983.

- Seymour, Adam and Robert Mabro, Energy Taxation and Economic Growth. Vienna: OPEC Fund for International Development, 1994

- Shojai, Siamack, ed. The New Global Oil Market: Understanding Energy Issues in the World Economy. Westport, Conn.: Praeger, 1995

- Shwadran, Benjamin. The Middle East, Oil and the Great Powers. New York: Praeger, 1955.

- Skeet, Ian. OPEC: Twenty-Five Years of Prices and Politics. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1988.

- Stobaugh, Robert, and Daniel Yergin. Energy Future: Report of the Harvard Business School Energy Project. New York: Random House, 1979.

- Szyliowicz, Joseph S., and Bard E. O’Neill, eds. The Energy Crisis and U.S. Foreign Policy. New York: Praeger, 1975.

- Tanzer, Michael. The Political Economy of International Oil and the Underdeveloped Countries. Boston: Beacon Press, 1969.

- Tomori, S. ed., Oil and gas sector in the Nigerian economy, Lagos: Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Lagos, 1991.

- Tugwell, Franklin. The Politics of Oil in Venezuela. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1975.

- Turner, Louis. Oil Companies and the International System. London: Allen and Unwin, 1978.

- U.S. Federal Trade Commission. International Petroleum Cartel. Staff Report to the Federal Trade Commission, 82nd Congress, 2nd sess. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1952.

- Vernon, Raymond. Two Hungry Giants: The US and Japan in the Quest for Oil and Ores. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1983.

External links

NOW on PBS: Oil, Politics & Bribes The scandalous connection between VECO Corporation—an Alaska-based oil services company—and Alaska's old-boy Republican network.

Peak Oil Core issues

Results/responses Hirsch report · Oil Depletion Protocol · Price of petroleum · 2000s energy crisis · Energy crisis · Export Land Model · Food vs fuel · Oil reserves · Pickens Plan · Swing producer · Transition TownsPeople Books Films A Crude Awakening · Collapse · The End of Suburbia · Oil Factor · PetroApocalypse Now? · How Cuba Survived Peak Oil · What a Way to GoOrganizations Other "peaks" Categories:

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.