- Black metal

-

This article is about the musical genre. For the Venom album, see Black Metal (album). For black minerals, see Black metal (mineralogy).

Black metal Stylistic origins Thrash metal, speed metal, hardcore punk Cultural origins First Wave:

Early-mid 1980s, European extreme metal scene

Second Wave:

Early 1990s, Scandinavian extreme metal sceneTypical instruments Vocals - Electric guitar - Bass guitar - Drums Mainstream popularity Moderate since the early 1990s in Norway, Finland and Sweden, undergound elsewhere Subgenres Symphonic black metal - Viking metal Fusion genres Blackened death metal Other topics List of bands Black metal is an extreme subgenre of heavy metal music. Common traits include fast tempos, shrieked vocals, highly distorted guitars played with tremolo picking, blast beat drumming, raw recording, and unconventional song structure.

During the 1980s, several thrash metal bands formed a prototype for black metal. This so-called "first wave" included bands such as Venom, Bathory, Hellhammer, Celtic Frost and Sarcófago.[1] A "second wave" arose in the early 1990s, spearheaded by Norwegian bands such as Mayhem, Burzum, Darkthrone, Immortal and Emperor. This scene developed the black metal style into a distinct genre.

Black metal has often been met with hostility from mainstream culture, mainly due to the misanthropic and anti-Christian standpoint of many artists. Moreover, several of the genre's pioneers have been linked with church burnings and murder. For these reasons and others, black metal is usually seen as an underground form of music. Additionally some have been linked to neo-Nazism, however it should be noted that many black metallers and most prominent black metal musicians reject Nazi ideology and oppose its influence on the black metal subculture.[2][3][4][5]

Contents

Characteristics

Instrumentation

Black metal guitarists usually favor high-pitched guitar tones and a great deal of distortion.[6] The guitar is usually played with much use of fast tremolo picking[6][7][8] and dissonance. Guitarists often use scales, intervals and chord progressions that yield the most fear-inducing and foreboding sounds. Guitar solos and low guitar tunings are rare in black metal.[8]

The bass guitar is seldom used to play stand-alone melodies. It is not uncommon for the bass guitar to be inaudible[8] (or almost inaudible) or to homophonically follow the bass lines of the guitar. Typically, drumming is fast-paced and uses double-bass and/or blast beats.

Black metal songs often stray from conventional song structure and often lack clear verse-chorus sections. Instead, many black metal songs contain lengthy and repetitive instrumental sections.

Vocals and lyrics

Traditional black metal vocals are high-pitched and raspy and include shrieking, screaming and snarling.[6][8] This is in stark contrast to the low-pitched growls of death metal.

The most common and founding lyrical theme is opposition to Christianity[8] and other organized religions. As part of this, many artists write lyrics that could be seen to promote atheism, antitheism, paganism or Satanism.[9] The hostility of many secular or pagan black metal artists is in some way linked to the Christianization of their countries. Other oft-explored themes are depression, nihilism, misanthropy,[9] death and other dark topics. However, over time, many black metal artists have begun to focus more on topics like the seasons (particularly winter), nature, mythology, folklore, philosophy and fantasy.

Production

Low-cost production quality was a must for early black metal artists with low budgets, where recordings would often take place in the home or in basements; a notable example of such is the band Mayhem, whose record label Deathlike Silence Productions would record artists in the basement of the shop Helvete.[6] However, even when they were able to raise their production quality, many artists chose to keep making low fidelity (lo-fi) recordings.[8][9] The reason for this was to stay true to the genre's underground roots and to make the music sound more "raw" and "cold".[9] One of the better-known examples of this is the album Transilvanian Hunger by Darkthrone – a band that has been said to "represent the DIY aspect of black metal" by Johnathan Selzer of Terrorizer magazine.[9] Many have claimed that, originally, black metal was not meant to attract a big audience.[9] Vocalist Gaahl said that during its early years, "black metal was never meant to reach an audience, it was purely for our own satisfaction".[7]

Imagery and performances

Unlike artists of other genres, many black metal artists do not perform concerts. Bands that choose to perform concerts often make use of stage props and theatrics. Mayhem and Gorgoroth among other bands are noted for their controversial shows; which have featured impaled animal heads, mock crucifixions, medieval weaponry, and band members doused in animal blood.[10]

Black metal artists often appear dressed in black with combat boots, bullet belts, spiked wristbands,[9] and inverted crosses/pentagrams to reinforce their anti-Christian or anti-religious stance.[1] However, the most stand-out trait is their use of corpse paint – black and white makeup (sometimes mixed with real or fake blood), which is used to create a corpse-like appearance.

In the early 1990s, most pioneering black metal artists used simple black-and-white pictures or writing on their record covers.[4] This could have been meant as a reaction against death metal bands, who at that time had begun to use brightly-colored album artwork.[4] Most underground black metal artists have continued this style. In the main, black metal album covers are usually atmospheric or provocative; some feature natural or fantasy landscapes (for example Burzum's Filosofem and Emperor's In The Nightside Eclipse) while others are violent, perverted and iconoclastic (for example Marduk's Fuck Me Jesus and Dimmu Borgir's In Sorte Diaboli).

First wave

The first wave of black metal refers to those bands during the 1980s who influenced the black metal sound and formed a prototype for the genre. They were often speed metal or thrash metal bands.[1][11]

The term "black metal" was coined by the English band Venom with their second album Black Metal (1982). Although deemed thrash metal rather than black metal by today's standards,[9] the album's lyrics and imagery focused more on anti-Christian and Satanic themes than any before it. Their music was fast, unpolished in production and with raspy or grunted vocals. Venom's members also adopted pseudonyms, a practice that would become widespread among black metal musicians.

Another major influence on black metal was the Swedish band Bathory, led by Thomas Forsberg (under the pseudonym Quorthon). Not only was Bathory's music fast, lo-fi and anti-Christian, Quorthon was also the first to use the "shrieked" vocals that came to define black metal. The band played in this style on their first four albums: Bathory (1984), The Return of Darkness and Evil (1985), Under the Sign of the Black Mark (1987) and Blood Fire Death (1988). At the beginning of the 1990s, Bathory pioneered the style that would become known as Viking metal.

Other artists usually considered part of this movement include Hellhammer and Celtic Frost (from Switzerland), Kreator, Sodom and Destruction (from Germany),[12] Bulldozer and Death SS (from Italy), Tormentor (from Hungary), Von (from USA), Sarcófago (from Brazil) and Blasphemy (from Canada).

Second wave

The second wave of black metal began in the early 1990s and was spearheaded by the Norwegian black metal scene. During 1990–1994 a number of Norwegian artists began performing and releasing a new kind of black metal music; this included Mayhem, Thorns, Burzum, Darkthrone, Immortal, Satyricon, Enslaved, Emperor, Dimmu Borgir, Gorgoroth, Ulver and Carpathian Forest. They developed the style of their 1980s forebears as a distinct genre that was separate from thrash metal. This was partly thanks to a new kind of guitar playing developed by 'Blackthorn' (Snorre Ruch) of Thorns/Stigma Diabolicum and 'Euronymous' (Øystein Aarseth) of Mayhem.[7] 'Fenriz' of Darkthrone has credited them with this innovation in a number of interviews. He described it as being "derived from Bathory"[13] and noted that "those kinds of riffs became the new order for a lot of bands in the '90s".[14] As seen below, some members of these Norwegian bands would be responsible for a spate of crimes and controversy, including church burnings and murder. Within this scene, an aggressive anti-Christian mindset became a must for any artists to be finalized as "black metal". 'Ihsahn' of Emperor believes that this trend may have developed simply from "an opposition to society, a confrontation to all the normal stuff".[15] Visually, the dark themes of their music was complemented with corpsepaint, which became a way for black metal artists to distinguish themselves from other metal bands of the era.[9]

In neighboring countries, bands began to adopt the style of the Norwegian scene. In Sweden this included Marduk, Dissection, Lord Belial, Dark Funeral, Arckanum, Nifelheim and Abruptum. In Finland, there emerged a scene that mixed the black metal style with elements of death metal and grindcore; this included Beherit, Archgoat and Impaled Nazarene. Black metal scenes also emerged on the European mainland during the early 1990s - again inspired by the Norwegian scene. In Poland, a scene was spearheaded by Graveland and Behemoth. In France, a close-knit group of musicians known as Les Légions Noires emerged; this included artists such as Mütiilation, Vlad Tepes, Belketre and Torgeist. Bands such as Von, Judas Iscariot, Demoncy and Profanatica emerged during this time in the United States, where thrash metal and death metal were more popular among extreme metal fans.

By the mid 1990s, the style of the Norwegian scene was being adopted by bands worldwide. Newer black metal bands also began raising their production quality and introducing additional instruments such as synthesizers and even full-symphony orchestras.

Helvete and Deathlike Silence

During May–June 1991,[16] Øystein Aarseth (aka 'Euronymous') of Mayhem opened an independent record shop named Helvete (Norwegian for hell) in Oslo. Musicians from Mayhem, Burzum, Emperor and Thorns often met there, and it became the foremost outlet for black metal records.[17] In its basement, Aarseth founded an independent record label named Deathlike Silence Productions. With the rising popularity of his band and others like it, the underground success of Aarseth's label is often credited for encouraging other record labels, that previously shunned black metal acts, to then reconsider and release their material.

Dead's suicide

On 8 April 1991, Mayhem vocalist Per Yngve "Pelle" Ohlin (aka 'Dead') committed suicide in a house shared by the band. While fellow musicians often described Ohlin as odd and introverted off-stage, his on-stage persona was very different. He went to great lengths to make himself look like a corpse and would cut his arms while singing.[7][18]

He was found with slit wrists and a shotgun wound to the head; the shotgun was owned by Mayhem guitarist Øystein Aarseth (aka 'Euronymous'). Ohlin's suicide note read "Please excuse all the blood" and included an apology for firing the weapon indoors. Before calling the police, Aarseth went to a nearby shop and bought a disposable camera to photograph the body, after re-arranging some items.[19] One of these photographs was later used as the cover of a bootleg live album called Dawn of the Black Hearts.[20]

In time, rumors spread that Aarseth had made a stew with bits of Ohlin's brain and had made necklaces with bits of his skull.[9] The band later denied the former rumor, but confirmed that the latter was true.[9][18] Moreover, Aarseth claimed to have given these necklaces to musicians he deemed worthy.[1] Mayhem bassist Jørn Stubberud (aka 'Necrobutcher') noted that "people became more aware of the [black metal] scene after Dead had shot himself ... I think it was Dead's suicide that really changed the scene".[21]

Two other members of the early Norwegian scene would later commit suicide: Erik Brødreskift aka 'Grim' (of Immortal, Borknagar, Gorgoroth) in 1999[22][23] and Espen Andersen aka 'Storm' (of Strid) in 2001.[24]

Church burnings

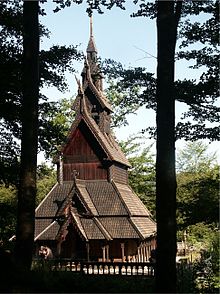

Musicians and fans of the Norwegian black metal scene took part in over 50 arsons of Christian churches in Norway from 1992 to 1996.[17] Some of the buildings were hundreds of years old and seen as important historical landmarks. One of the first and most notable was Norway's Fantoft stave church, which police believed was burnt by Varg Vikernes of the one-man band Burzum.[17] However, Vikernes would not be charged until his arrest for the murder of Øystein Aarseth ('Euronymous') in 1993 (see below). The cover of Burzum's EP Aske (Norwegian for ashes) is a photograph of the Fantoft stave church after the arson. The musicians Samoth,[25] Faust,[25] and Jørn Inge Tunsberg[17] were also convicted for church arsons.

Today, opinions on the church burnings differ within the black metal community. Guitarist Infernus and former vocalist Gaahl of the band Gorgoroth have praised the church burnings in interviews, with the latter saying "there should have been more of them, and there will be more of them".[1] However, Necrobutcher and Kjetil Manheim of Mayhem have berated the church burnings, with the latter claiming "It was just people trying to gain acceptance within a strict group [the black metal scene] ... they wanted some sort of approval and status".[26]

Euronymous's murder

On 10 August 1993, Varg Vikernes of Burzum murdered Mayhem guitarist Øystein Aarseth (aka 'Euronymous'). That night, Vikernes and Snorre Ruch of Thorns traveled from Bergen to Aarseth's apartment in Oslo. Upon their arrival a confrontation began, which ended when Vikernes fatally stabbed Aarseth. His body was found outside the apartment with 23 cut wounds – two to the head, five to the neck, and 16 to the back.[27]

It has been speculated that the murder was the result of a power struggle, a financial dispute over Burzum records, or an attempt at "out doing" a stabbing in Lillehammer the year before by another black metal musician, Bard 'Faust' Eithun.[28] Vikernes claims that Aarseth had plotted to torture him to death and videotape the event – using a meeting about an unsigned contract as a pretext.[29] On the night of the murder, Vikernes claims he intended to hand Aarseth the signed contract and "tell him to fuck off", but that Aarseth attacked him first.[29] Vikernes also said that most of Aarseth's cut wounds were caused by broken glass he had fallen on during the struggle.[29]

Whatever the circumstances, Vikernes was arrested within days and in May 1994 was sentenced to 21 years in prison for the murder and for four church burnings. Vikernes smiled at the moment his verdict was read and the image was widely reprinted in the news media.[29] In May 1994, Mayhem finally released the album De Mysteriis Dom Sathanas, which features Aarseth on electric guitar and Vikernes on bass guitar. In 2003, Vikernes failed to return to Tønsberg prison after being given a short leave. He was re-arrested shortly after while driving a stolen car with various weapons.[30] Vikernes was released on parole in 2009.[31][32]

Conflict between scenes

There was said to have been a strong rivalry between Norwegian black metal and Swedish death metal scenes. Fenriz and Tchort have noted that Norwegian black metal musicians had become "fed up with the whole death metal scene"[4] and that "death metal was very uncool in Oslo" at the time.[26] A number of times, Euronymous sent death threats to some of the more mainstream death metal groups in Europe.[26] Allegedly, a group of Norwegian black metal fans even plotted to kidnap and murder certain Swedish death metal musicians.[26]

A brief feud between Norwegian and Finnish scenes gained some media recognition[citation needed] during 1992 and 1993. The feud was partly motivated by seemingly harmless pranks; for example Nuclear Holocausto of the Finnish band Beherit made prank calls in the middle of the night to Samoth of Emperor (in Norway) and Mika Luttinen of Impaled Nazarene (in Finland). The calls consisted of senseless babbling and playing of children's songs,[33] although Luttinen believed them to be death threats from Norwegian bands.[citation needed]

Notably, the album cover of Impaled Nazarene's Tol Cormpt Norz Norz Norz has "No orders from Norway accepted" and "Kuolema Norjan kusipäille!" ("Death to the assholes of Norway!") printed on the back. The Finnish band Black Crucifixion criticized Darkthrone as "trendies" due to Darkthrone originally being a death metal band.[34]

Stylistic divisions

- Symphonic black metal is a style of black metal that uses symphonic and orchestral elements. This may include the usage of instruments found in symphony orchestras (piano, violin, cello, flute and keyboards), 'clean' or operatic vocals and guitars with less distortion.

- Viking metal are terms used to describe black metal bands who incorporate various kinds of folk music. Viking black metal bands focus solely on Nordic folk music and mythology. Their harsh black metal sound is "often augmented by sorrowful keyboard melodies".[35] Vocals are typically a mixture of high-pitched shrieks and 'clean' choral singing.[36] The origin of Viking metal can be traced to the albums Blood Fire Death (1988) and Hammerheart (1990) by the Swedish band Bathory.[37] In the mid 1990s, Irish bands such as Cruachan[38] and Primordial[39] began to combine black metal with Irish folk music.

- Blackened death metal is a style that combines death metal and black metal.[40][41]

Ideology

Black metal is generally opposed to Christianity and supportive of individualism.[1] Arguably, this is the only coherent sentiment among black metal artists. In a Norwegian documentary, Fenriz stated that "black metal is individualism above all".[42] Artists who oppose Christianity tend to promote atheism, antitheism, paganism, or Satanism.[1] Some musicians – such as Euronymous, Infernus and Erik Danielsson – have insisted that Satanism should be foremost.[43][44] Occasionally, artists write lyrics that appear to be nihilistic and misanthropic,[9] although it is debatable whether this represents their mentality. In some cases, black metal artists have also espoused romantic nationalism, although the majority of those involved are not outspoken with regard to this. Nonetheless, many black metal artists seek to reflect their surroundings within their music. The documentarist Sam Dunn noted of the Norwegian scene that "unlike any other heavy metal scene, the culture and the place is incorporated into the music and imagery".[1]

Regarding the sound of black metal, there are two conflicting groups within the genre – "those that stay true to the genre's roots, and those that introduce progressive elements".[9] The former believe that the music should always be minimalist – performed only with the standard guitar-bass-drums setup and recorded in a low fidelity style. One supporter of this train of thought is Blake Judd of Nachtmystium, who has rejected labeling his band black metal for its departure from the genre's typical sound.[45] A supporter of the latter is Snorre Ruch of Thorns, who stated that modern black metal is "too narrow" and believes that this was "not the idea at the beginning".[46]

Some prominent black metal musicians believe that black metal does not need to hold any ideologies. For example, Jan Axel Blomberg said in an interview with Metal Library that "In my opinion, black metal today is just music."[47] Likewise, Sigurd Wongraven stated in the Murder Music documentary that black metal "doesn't necessarily have to be all Satanic, as long as it's dark."[9]

To this day, there are still many bands who believe in specific philosophies and ideologies. Aaron Weaver from Wolves in the Throne Room stated in an interview with Brooklyn Vegan, "I think that black metal is an artistic movement that is critiquing modernity on a fundamental level saying that the modern world view is missing something."[48]

Unblack metal

Unblack metal, or Christian black metal, is a term used to describe musically black metal sounding artists whose lyrics and imagery promote Christianity.[49] The Australian band Horde's debut album Hellig Usvart, released through Nuclear Blast Records, is often credited for being the first Christian black metal album, though the sole member, Anonymous, has stated that "there were similar [unblack] bands prior to Horde, even in Norway," referring to the band Antestor who formed in 1990, although prior to 1993 they were a death/doom band called Crush Evil. Hellig Usvart caused great controversy in the black metal scene, and death threats were sent to Nuclear Blast Records headquarters demanding them to release the members' names. The name of Anonymous was later revealed as Jayson Sherlock, a drummer for Mortification and Paramaecium.

Many in the black metal scene see "Christian black metal" as an oxymoron.[50] On the British black metal documentary Murder Music: A History of Black Metal (2007), all interviewed musicians stated when asked about the matter that black metal cannot be Christian.[9] The term "Christian black metal" drew confused replies from the black metal musicians, for example Martin Walkyier of the English metal band Sabbat commented: "'Christian black metal?' What do they do? Do they build churches? Do they repair them? (laughs)"[9] Early groups such as Horde and Antestor refused to call their music "black metal" because they felt that the style was strongly associated with Satanism. Horde called its music "holy unblack metal," and Antestor preferred to call their music "sorrow metal" instead.[51] However, many current Christian black metal bands, such as Crimson Moonlight, feel that black metal has changed from an ideological movement to a purely musical genre, and that is why they also call their music black metal.[50]

National Socialist black metal

National Socialist black metal (NSBM) is a term used for black metal artists who promote National Socialist (Nazi) beliefs through their music and imagery. NSBM is not regarded as a distinct subgenre, as there is no way to play black metal in a National Socialist way. Some black metal bands have made references to Nazi Germany for shock value, causing them to be wrongly labeled as NSBM. Due to his writings,[52] Varg Vikernes is regarded as the main inspiration for the NSBM movement. Vikernes, however, has tried to distance himself from Nazism and the NSBM scene, preferring to refer to himself as an odalist instead of a "socialistic", "materialistic" Nazi.[52]

NSBM artists are a small minority within black metal, according to Mattias Gardel.[53] They have been criticized by some prominent and influential black metal musicians – including Jon Nödtveidt,[54] Tormentor,[55] King ov Hell,[2] Infernus,[3] Lord Ahriman,[4] Emperor Magus Caligula,[4][5] Richard Lederer,[56] Michael W. Ford[57] and the members of Arkhon Infaustus.[4] They categorize Nazism alongside Christianity as authoritarian, collectivist, and a "herd mentality".[54][55]

Media

Documentaries on black metal:

- Det Svarte Alvor (1994).

- Satan Rides the Media (1998).

- Norsk Black Metal (2003) was aired on Norwegian TV by the Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation (NRK).

- Metal: A Headbanger's Journey (2005) touches on black metal in the early 1990s, and includes an extensive 25-minute feature on the DVD release.

- True Norwegian Black Metal (2007) was aired as a five-part feature by the online broadcasting network VBS.tv. It explores some of the aspects of the lifestyle, beliefs and controversies surrounding former Gorgoroth vocalist Gaahl.[58]

- Black Metal: A Documentary (2007), produced by Bill Zebub, explores the world of black metal from the point of view of the artists. There is no narrator and no one outside of black metal takes part in any interview or storytelling.

- Murder Music: A History of Black Metal (2007).

- Once Upon a Time in Norway (2008).

- Until The Light Takes Us (2009) explores black metal's origins and subculture, including "exclusive interviews" and "rare, seldom seen footage from the Black Circle's earliest days".[59]

References in media:

- The black metal mockumentary Legalize Murder was released in 2006.

- The cartoon show Metalocalypse is about an extreme metal band called Dethklok, with many references to leading black metal artists on the names of various businesses such as Fintroll's convenience store, Dimmu Burger, Gorgoroth's electric wheelchair store, Carpathian Forest High School, Marduk's Putt & Stuff, Burzum's hot-dogs and Behemoth studios (as well as the man who owns Behemoth studios, whose name is Mr. Grishnackh). In the episode Dethdad, Dethklok travels to Norway to both visit Toki's dying father and the original black metal record store, much to the dismay of the band members when they find out the store doesn't sell any of their music, as described by the owner for being "too digital."

- A Norwegian commercial for a laundry detergent once depicted black metal musicians as part of the advertisement.[60]

- Black metal bands such as 1349, Emperor, Behemoth, Dimmu Borgir, Enslaved and Satyricon have had their videos make appearances on MTV's Headbangers Ball.

- Comedian Brian Posehn made a visual reference to Norwegian black metal bands in the music video for his comedy song "Metal By Numbers".[61]

- A KFC commercial screened in Canada (2008) and Australia (2010) featured a fictional black metal band called Hellvetica. Onstage, the band's singer does a fire-eating trick. Once backstage, he takes a bite of the spicy KFC chicken and declares "Oh man, that is hot".

- An episode of Bones featured the discovery of a human skeleton at a black metal concert in Norway. The episode was called "Mayhem on a Cross". It was the 21st episode of the 4th season.

- There are many references to black metal bands (Bathory, Marduk, Cradle of Filth, Dimmu Borgir) in Åke Edwardson's 1999 crime novel Sun and Shadow (Sol och skugga). The plot involves the music of a fictional Canadian black metal band called "Sacrament". As part of the inquiry, Inspector Winter tries to distinguish between black and death metal artists (Originally published in Swedish. English language first edition in 2005).[citation needed][62]

See also

Further reading

- Ekeroth, Daniel (2008). Swedish Death Metal. Bazillion Points Books. ISBN 978-0-9796163-1-0

- Moynihan, Michael. Lords of Chaos: The Bloody Rise of the Satanic Metal Underground. Venice: Feral House, 2006. ISBN 0-922915-48-2

- Kahn-Harris, Keith. Extreme Metal: Music and Culture on the Edge. Oxford: Berg, 2006. ISBN 978-1-84520-399-3

- Christe, Ian. Sound of the Beast: the Complete Headbanging History of Heavy Metal. New York: Harper Collins, 2004.

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h Dunn, Sam (2005). Metal: A Headbanger's Journey.

- ^ a b Interview with JOTUNSPOR :: Maelstrom :: Issue No 50

- ^ a b BLABBERMOUTH.NET - GORGOROTH Guitarist INFERNUS: 'I Personally Am Against Racism In Both Thought And Practice'

- ^ a b c d e f g Zebub, Bill (2007). Black Metal: A Documentary.

- ^ a b YouTube - Dark Funeral - Interview (Episode 276)

- ^ a b c d Kahn-Harris, Keith (2006). Extreme Metal: Music and Culture on the Edge, page 4.

- ^ a b c d Campion, Chris (February 20, 2005). "In the Face of Death". The Guardian.

- ^ a b c d e f Kalis, Quentin (August 31, 2004). "Black Metal: A Brief Guide". Chronicles of Chaos.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Dome, Michael (2007). Murder Music – Black Metal. Rockworld TV.

- ^ "Norwegian black metal band shocks Poland". Aftenposten. February 4, 2004.

- ^ Sharpe-Young, Garry. Metal: The Definitive Guide, page 208

- ^ Lahdenpera, Esa. Interview with Euronymous. Kill Yourself #2. August 1993.

- ^ Until the Light Takes Us (2009)

- ^ "Web-exclusive interview: Darkthrone's Fenriz (Part 2)". Revolver. 14 January 2010.

- ^ Lords of Chaos (1998): Ihsahn interview

- ^ In May or June 1991, according to the Interview with Bård Eithun. Lords of Chaos (1998), page 66.

- ^ a b c d Grude, Torstein (1998). Satan Rides The Media.

- ^ a b Hellhammer interviewed by Dmitry Basik (June 1998)

- ^ Lords of Chaos (1998): Hellhammer interview

- ^ Sounds of Death magazine (1998): Hellhammer interview

- ^ Unrestrained magazine #15: Necrobutcher interview[dead link]

- ^ MusicMight: Biography of Immortal

- ^ [http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=19441 Find A Grave: Erik "Grim" Brødreskift (1969-1999)

- ^ "Espen Andersen". Encyclopaedia Metallum. Retrieved 2011-11-05.

- ^ a b Lords of Chaos (1998), page 79

- ^ a b c d Martin Ledang, Pål Aasdal (2008). Once Upon a Time in Norway.

- ^ Steinke, Darcey. "Satan's Cheerleaders" SPIN Magazine, February 1996.

- ^ Steve Huey (1993-08-10). "Mayhem Mayhem Biography on Yahoo! Music". Music.yahoo.com. http://music.yahoo.com/ar-257375-bio. Retrieved 2010-03-24.

- ^ a b c d "Varg Vikernes - A Burzum Story: Part II - Euronymous". Burzum.org. http://www.burzum.org/eng/library/a_burzum_story02.shtml. Retrieved 2010-03-24.

- ^ "Police nab 'The Count' after he fled jail". Aftenposten. October 27, 2003.

- ^ "Varg Vikernes ute på prøve" (in Norwegian). Verdens Gang. NTB (Oslo, Norway). 10 March 2009. Archived from the original on 10 March 2009. http://www.webcitation.org/query?url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.vg.no%2Fnyheter%2Finnenriks%2Fartikkel.php%3Fartid%3D557287&date=2009-03-10. Retrieved March 10, 2009.

- ^ "Ute av fengsel" (in Norwegian). Dagbladet.no. 22 May 2009. http://www.dagbladet.no/2009/05/22/nyheter/black_metal/varg_vikernes/6354526/. Retrieved 23 May 2009.

- ^ "The End of a Legend - Isten smokes Holocaust Vengeance out of Beherit". Isten 6: 44–45. 1995.

- ^ "The Oath of the Goat's Black Blood". Sinister Flame 1: 28–32. 2003.

- ^ "Scandinavian Metal". Allmusic. http://www.allmusic.com/explore/style/d11954. Retrieved 2008-06-16.

- ^ Rivadavia, Eduardo. "Requiem review". Allmusic. http://www.allmusic.com/album/r280988. Retrieved 2008-03-27.

- ^ Rivadavia, Eduardo. "Blood Fire Death review". Allmusic. http://www.allmusic.com/artist/p3636/biography. Retrieved 2008-03-27.

- ^ Bolther, Giancarlo. "Interview with Keith Fay of Cruachan". Rock-impressions.com. http://www.rock-impressions.com/cruachan_inter1e.htm. Retrieved 2008-03-10.

- ^ Monger, James Christopher. "AMG Primordial". Allmusic. http://www.allmusic.com/artist/p320620. Retrieved 2008-03-12.

- ^ Henderson, Alex. "Ninewinged Serpent review". Allmusic. http://www.allmusic.com/album/r1241205. Retrieved 2009-05-03.

- ^ Bowar, Chad. "Venganza review". About.com. http://heavymetal.about.com/od/reviews/gr/hacavitz.htm. Retrieved 2009-05-03.

- ^ Norsk Black Metal (2003). Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation.

- ^ "Interviews:Gorgoroth". Live-Metal.Net. http://www.live-metal.net/features_interviews_infernus_gorgoroth.html. Retrieved 2010-03-24.

- ^ Interview with WATAIN

- ^ "Nachmystium shines black light on black metal". Daily Herald. June 20, 2008.

- ^ Thorns interview. Voices From The Darkside.

- ^ Skogtroll (January 7, 2007). Hellhammer (Jan Axel Blomberg) interview (in Russian (google-translated to English). Metal Library. Open Publishing. Retrieved on 2008-06-24.

- ^ Interview with Wolves in the Throne Room.

- ^ Kapelovitz, Dan (February 2001). "Heavy Metal Jesus Freaks - Headbanging for Christ". Mean Magazine. http://www.kapelovitz.com/christianmetal.htm. Retrieved 2007-09-06. "And where secular Black Metal thrived, so did its Christian counterpart, Unblack Metal, with names like Satanicide, Neversatan, and Satan's Doom."

- ^ a b Jordan, Jason (2005). "Crimson Moonlight - At Their Most Brutal". Ultimate Metal webzine. Ultimatemetal.com. http://www.ultimatemetal.com/forum/interviews/195667-crimson-moonlight-their-most-brutal.html. Retrieved 2005-05-15.

- ^ Morrow, Matt (2001). "Antestor - Det Tapte Liv Death". The Whipping Post. Open Publishing. http://thewhippingpost.tripod.com/antestordettapteliv.htm. Retrieved 2007-08-29.

- ^ a b "Varg Vikernes - A Burzum Story: Part VII - The Nazi Ghost". Burzum.org. http://www.burzum.org/eng/library/a_burzum_story07.shtml. Retrieved 2010-03-24.

- ^ Gardel, Mattias. Gods of the Blood (2003)

- ^ a b "DISSECTION. Interview with Jon Nödtveidt, June 2003". Metalcentre.com. http://www.metalcentre.com/webzine.php?p=interviews&lang=eng&nr=123. Retrieved 2010-03-24.

- ^ a b Metal Heart 2/00

- ^ "Political Statements from Protector (Summoning)". Summoning.info. http://www.summoning.info/Stuff/PoliticalStatements.html. Retrieved 2010-03-24.

- ^ Interview with Michael Ford by Eosforos for Full Moon Productions.

- ^ "YouTube". YouTube. 2007-04-25. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i4U33U_UyzQ. Retrieved 2010-03-24.

- ^ Until the Light Takes Us (2008)

- ^ Christe, Ian (2001). Sound of The Beast: The Headbanging History of Heavy Metal, page 289.

- ^ "Brian Posehn - Metal By Numbers". YouTube. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=chiVMrWMHko. Retrieved 2010-03-24.

- ^ Edwardson, Åke (2005). Sun and Shadow. Viking Adult, New York. 400 pages. ISBN 0-670-03415-0. (originally published in Swedish in 1999).

Heavy metal Subgenres Alternative metal · Avant-garde metal · Black metal · Christian metal · Crust punk · Death metal · Djent · Doom metal · Drone metal · Extreme metal · Folk metal · Funk metal · Glam metal · Gothic metal · Grindcore · Groove metal · Industrial metal · Metalcore · Neo-classical metal · Nintendocore · Nu metal · Post-metal · Power metal · Progressive metal · Rap metal · Sludge metal · Speed metal · Stoner metal · Symphonic metal · Thrash metal · Traditional heavy metal · Viking metalNotable scenes Culture Heavy metal subculture · Fashion · Subgenres · Bands · Festivals · Umlaut · Headbanging · Sign of the horns Portal:Heavy metal

Portal:Heavy metalExtreme metal Genres Sub-genres Black metal: National Socialist black metal - Symphonic black metal - Unblack metal - Viking metal

Death metal: Melodic death metal - Technical death metal

Doom metal: Epic doom - Stoner doom - Traditional doomFusion genres Crossover thrash - Crust punk - Death/doom - Drone metal - Grindcore - Metalcore (Deathcore - Mathcore - Nintendocore) - Sludge metalNotable scenes Categories:- European culture

- Heavy metal subgenres

- Black metal

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.