- Monadnock Building

-

Monadnock BuildingChicago Landmark

Building seen from Dearborn street in 2005. The north half is in the foreground.Location in Chicago Loop

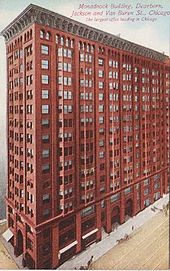

Building seen from Dearborn street in 2005. The north half is in the foreground.Location in Chicago LoopLocation: Chicago, Illinois Coordinates: 41°52′39″N 87°37′46″W / 41.8775°N 87.62944°W Built: 1891–1893 Architect: Burnham & Root and Holabird & Roche Part of: South Dearborn Street–Printing House Row North Historic District[1] (#76000705) NRHP Reference#: 70000236 Significant dates Added to NRHP: November 20, 1970[3] Designated CL: November 14, 1973[2] The Monadnock Building (historically the Monadnock Block; pronounced /məˈnædnɒk/ mə-nad-nok), is a skyscraper located at 53 West Jackson Boulevard in the south Loop community area of Chicago, Illinois. The north half of the building was designed by the firm of Burnham & Root and built in 1891. The tallest commercial load-bearing masonry building ever constructed, it employed the first portal system of wind bracing in America. Its decorative staircases represent the first use of aluminum in building construction. The south half, constructed in 1893, was designed by by Holabird & Roche and is similar in color and profile to the original, but the design is more traditionally ornate. When completed, it was the largest office building in the world. The success of the building was the catalyst for an important new business center at the southern end of the Loop.

The building was remodelled in 1938 in one of the first major skyscraper renovations ever undertaken—a bid, in part, to revolutionize how building maintenance was done and halt the demolition of Chicago's aging skyscrapers. It was sold in 1979 to owners who restored the building to its original condition, in one of the most comprehensive skyscraper restorations attempted as of 1992. The project was recognized as one of the top restoration projects in the country by the National Trust for Historic Preservation in 1987. The building is divided into offices from 250 square feet (23 m2) to 6,000 square feet (560 m2) in size, and primarily serves independent professional firms. It was listed for sale in 2007.

The north half is an unornamented vertical mass of purple-brown brick, flaring gently out at the base and top, with vertically continuous bay windows projecting out. The south half is vertically divided by brickwork at the base and rises to a large copper cornice at the roof. Projecting window bays in both halves allow large exposures of glass, giving the building an open appearance despite its mass. The Monadnock is part of the Printing House Row District, which also includes the Fisher Building, the Manhattan Building, and the Old Colony Building.

When it was built, many critics called the building too extreme, and lacking in style. Others found in its lack of ornamentation the natural extension of its commercial purpose and an expression of modern business life. Early 20th century European architects found inspiration in its attention to purpose and functional expression. It was one of the first buildings named a Chicago Architectural Landmark in 1958. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1970, and named as part of the National Historic Landmark South Dearborn Street–Printing House Row North Historic District in 1976. Modern critics have called it a "classic", a "triumph of unified design", and "one of the most exciting aesthetic experiences America's commercial architecture has produced".[4]

Contents

History

North half (1881–1891)

The Monadnock was commissioned by Boston real estate developers Peter and Shepherd Brooks in the building boom following the Depression of 1873–79.[5] The Brooks family, which had amassed a fortune in the shipping insurance business and had been investing in Chicago real estate since 1863, had retained Chicago property manager Owen F. Aldis to manage the construction of the seven-story Grannis Block on Dearborn Street in 1880.[6] It was Aldis, one of two men Louis Sullivan credited with being "responsible for the modern office building",[7]a[›] who convinced investors like the Brooks brothers to build new skyscrapers in Chicago. By the end of the century, Aldis would create over 1,000,000 square feet (93,000 m2) of new office space and manage nearly one fifth of the office space in the Loop.[8][9]

Daniel Burnham and John Wellborn Root met as young draftsmen in the Chicago firm of Carter, Drake, and Wight in 1872 and left to form Burnham & Root the following year.[10] At Aldis's urging, the Brooks brothers had retained the then-fledgling firm to design the Grannis Block, which was their first major commission.[11] Burnham and Root would become the architects of choice for the Brooks family, for whom they would complete the first high-rise building in Chicago, the 10-story Montauk Building, in 1883, and the 11-story Rookery Building in 1888.[12]

The Great Chicago Fire of 1871 had decimated a 4-mile (6.4 km) by 0.5-mile (0.80 km) swath of the city between the Chicago River and Lake Michigan, and subsequent commercial development expanded into the area far south of the main business district along the river that would come to be known as "the Loop".[13] Between 1881 and 1885, Aldis bought a series of lots in the area on Peter Brooks' behalf, including a 70-by-200-foot (21 by 61 m) site on the corner of Jackson and Dearborn streets.[14] The location was remote, yet attractive for several reasons. The construction of the Chicago Board of Trade Building in 1885 had made nearby LaSalle Street the city's prime financial district, driving up property values, and railroad companies were buying up land further south for new terminal buildings, creating further speculation in the southeastern end of the Loop.[15] Brooks commissioned Burnham & Root to design a building for the site in 1884, and the project was announced in 1885, with a brief trade journal notice that the building would cost $850,000 ($20.7 million in 2011 dollars).[16][17] The Chicago building community had little faith in Brooks' choice of location. Architect Edwin Renwick would say:

When Owen Aldis put up the Monadnock on Jackson Boulevard there was nothing on the south side of the street between State Street and the river but cheap one-story shacks, mere hovels. Every one thought Mr. Aldis was insane to build way out there on the ragged edge of the city. Later when he carried the building on through Van Buren Street they were sure he was.[18]

Early sketches show a 13-story building with Ancient Egyptian ornament and a slight flaring at the top, divided visually into five sections with a lotus-blossom decorative motif. This design was never approved, as Brooks waited for the real estate market in the south Loop, still mostly warehouses, to improve.[17] Where Root was known for the detailed ornamentation of his designs (as seen in the Rookery Building), Brooks was known for his stinginess and preference for simplicity. For the Monadnock, Brooks insisted that the architects refrain from elaborate ornamentation and produce instead "the effect of solidity and strength, or a design that will produce that effect, rather than ornament for a notable appearance."[19] In a 1884 letter to Aldis, he wrote:

My notion is to have no projecting surfaces or indentations, but to have everything flush.... So tall and narrow a building must have some ornament in so conspicuous a situation... [but] projections mean dirt, nor do they add strength to the building...one great nuisance [is] the lodgment of pigeons and sparrows.[20]

While Root was on vacation, Burnham had a draftsman create a "straight up-and-down, uncompromising, unornamented facade."[21] Objecting at first, Root later threw himself into the design, declaring that the heavy lines of an Egyptian pyramid had captured his imagination and that he would "throw the thing up without a single ornament".[17][22]

In 1889, a new plan was announced for the building: a thick-walled brick tower, 16 stories high, devoid of ornamentation and suggestive of an Egyptian pylon.[17][23] Brooks insisted that the building have no projections, for which reason the plan did not include bay windows, but Aldis argued that more rentable space would be created by projecting oriel windows, which were included in the final design.[24] The Monadnock's final height was calculated to be the highest economically viable for a load-bearing wall design, requiring walls 6 feet (1.8 m) thick at the bottom and 18 inches (46 cm) thick at the top. Greater height would have required walls of such thickness that they would have reduced the rentable space too greatly. The final height was much dithered over by the owners, but a decision was forced when the city proposed an ordinance restricting the height of buildings to 150 feet (46 m).[25] To protect future income potential, Aldis sought a permit for a 16-story building immediately. The building commissioner, although "staggered by the sixteen story plan",[24] granted the permit on June 3, 1889.[24]

With its 17 stories (16 rentable plus an attic), its 215 feet (66 m) high load-bearing walls were the tallest of any commercial structure in the world.[26]b[›] To support the towering structure and reinforce against wind, the masonry walls were braced with an interior frame of cast and wrought iron. Root devised for this frame the first attempt at a portal system of wind bracing in America, in which iron struts were riveted between the columns of the frame for reinforcement.[22]c[›] The narrow lot allowed only a single, double-loaded corridor, which was appointed with a 3-foot (0.91 m) high wainscot of white Carrara marble, red oak trim, and feather-chipped glassd[›] that allowed outside light to filter from the offices on each side into the hallways. Floors were covered with hand-carved marble mosaic tiles.[27] Skylit open staircases were made of bronze-plated cast iron on upper floors.[28] On the ground floor, they were crafted in cast aluminum—an exotic and expensive material at the time—representing the first use of aluminum in building construction.[17][29]e[›]

The building was constructed by the firm of George A. Fuller, who trained as an architect but made his mark as the creator of the modern contracting system in building construction. His firm had supervised construction of the Rookery, and later built New York's Flatiron Building with Burnham in 1902.[30][31] The Monadnock Block was built as a single structure but was legally two buildings, the Monadnock and the Kearsarge, named for Mount Monadnock and Mount Kearsage in New Hampshire.f[›] Work was completed in 1891. The Monadnock, which Root called his "Jumbo", was his last project; he died suddenly while it was under construction.[32][33]

South half and early history (1891–1938)

Encouraged by the early success of the building, Shepherd Brooks purchased the 68-by-200-foot (21 by 61 m) lot adjoining to the south in 1893 for $360,000 ($8.77 million in 2011 dollars).[16][34] Aldis recommended the firm of Holabird & Roche, who had designed the Pontiac Building for Peter Brooks in 1891, to extend the Monadnock south to Van Buren.[35][36] William Holabird and Martin Roche had trained together in the office of William LeBaron Jenney, and in 1881 formed their own firm, which would become one of the most prolific in the city and the acknowledged leader of the Chicago school of architecture.g[›] The north half had struggled with cost overruns and Holabird & Roche presented a far more cost-effective design.[37] The design, for two buildings called the Katahdin and Wachusett (also named for New England mountains), connected them to the north half as a single structure at an estimated cost of $800,000 ($19.5 million in 2011 dollars).[16][38][39] Construction began in 1892, under the supervision of Corydon T. Purdy who would later earn accolades as the structural engineer for many famous Chicago and New York skyscrapers.[40]

The addition, 17 stories high, preserved the color and vertically massed profile of the original, but was more traditionally ornate in its design, with grander entranceways and more neoclassical touches.[41] The building reflected in its design the transition taking place in skyscraper design from load-bearing walls to steel frame construction .[26] The Katahdin, built first, used the same iron framed masonry construction as the original. The Wachusett was entirely steel framed.[42] Where the north half required great thicknesses of brick in the load-bearing walls, the addition employed only a thin facing of brick and terracotta trim, affording larger expanses of glass and faster, less expensive construction.[41] The south half cost 15 percent less, weighed 15 percent less, and had 15 percent more rentable space than the north half.[43] Connected on every floor except the top one and sharing a common basement, each of the four component buildings was equipped with its own heating system, elevators, stairs, and plumbing to facilitate a separate sale if required.[26] The combined final cost in 1893 was $2.5 million ($60.9 million in 2011 dollars).[16][44]

When complete, the Monadnock was the largest office building in the world, with 1,200 rooms and an occupancy of over 6,000.[45][46] The Chicago Daily Tribune commented that the population of most Illinois towns in 1896 would fit comfortably in the building.[47][48] It was a postal district unto itself, with four full-time carriers delivering mail six times a day, six days a week.[49] It was the first building in Chicago wired for electricity, and one of the first to be fire-proofed, with hollow fire clay tiles lining the structure so that the metal frame would be protected even if the facing brick were to be destroyed.[50][51]

Bird's-eye view of the southeast Loop, looking south from Adams street, in 1898. The completed Monadnock (7) is to the top right. Rand McNally called these buildings "some of the most remarkable buildings in the world".[52]

The Brooks' decision to construct a building of such scale and in such an unlikely location was vindicated by the Monadnock's success—it was the most profitable investment they ever made.[21] The Economist, a Chicago real estate journal, conceded in 1892 that:

the rapidity with which the Monadnock and Kearsarge ... have been rented is one of the phenomenal features in the real estate market of this city. The erecting and successful renting of these structures has simply established, in an incredibly short period of time, an important business center at the southwest corner of Jackson and Dearborn streets, a point which was but a short time ago considered too far south for a prosperous business center.[53]Early tenants, according to Rand McNally, included "great corporations, banks, and professional men ... among them the Santa Fe, the Michigan Central, and the Chicago & Alton Railroads, and the American Exchange National and Globe Savings Banks".[44] In 1897, the Union Elevated Railroad Company opened the Union Loop line of the Chicago "L", the last leg of which ran immediately alongside the Van Buren side of the building.[54]h[›] Aldis filed suit against the "L" in 1901 for $300,000 in damages ($7.89 million in 2011 dollars), complaining that:

[the] means of access to the said building ... had been cut off and the light, air, and view obstructed, and the enjoyment of the property disturbed by the throwing of smoke, dust, cinders, and filth ... by the creating and causing of loud and ominous noises, and by the causing of the ground to shake and vibrate ... said building and premises are greatly damaged.[16][55][56]Aldis lost the case, but won on appeal, when the Supreme Court of Illinois found that owners of property abutting the "L" lines could recover damages if the property had been injured by noise, vibration, or the blocking of light, paving the way for many lawsuits to follow.[57][58]

Modernization (1938–1979)

A boom in new construction after 1926 created stiff competition for older buildings like the Monadnock. Occupancy declined from 87 percent in 1929 to 55 percent in 1937 and the building began to lose money.[59] In 1938, building manager Graham Aldis (Owen's nephew) announced what the Chicago Daily Tribune called "the city's largest and most novel modernization job"[60] in a move toward halting the destruction of Chicago's aging skyscrapers. Rejecting the term "modernization", Aldis called his plan "progressive styling", which he believed would revolutionize the way building maintenance was done to preserve millions of dollars worth of buildings that would otherwise be destroyed. "There is no reason why", he said, "any well-designed office building need be torn down because of obsolescence."[60] Skidmore & Owings, who had pioneered functional design, were retained to lead a $125,000 program ($1.95 million in 2011 dollars) to restyle the main entrance, remodel the lobby and ground floor shops, modernize all the public spaces, and progressively modernize office suites as demand required.[16][59] The modernization included covering the mosaic floors with rubber tile and terrazo, enclosing the elevators and ornamental stairways, and replacing the marble and oak finishes in the corridors and offices with modern materials.[60] By the end of 1938, 35 new tenants had signed leases and 11 existing tenants had leased additional space in the building.[61]

In 1966, Aldis & Co., which had managed the building for the Brooks estate for 75 years, was dissolved and the Monadnock was sold for $2 million ($13.5 million in 2011 dollars) to Sudler & Co., owners of the John Hancock Center, the Rookery, and the Old Colony Building.[16][62][63] The new owners again modernized the interior, installing carpet, fluorescent lights, and new doors, and undertook a major effort to shore up the north wall which had sunk 1.75 inches (44 mm) during construction of the Kluczynski Federal Building across Jackson Street in 1974.[62][64]

By 1977, operating expenses were high, rents were low, and occupancy had fallen to 80 percent.[65][66] Struggling to make loan payments, the owners were forced to sell the building to avoid foreclosure.[65][66] It was purchased by a partnership headed by William S. Donnell in 1979 for $5 per square foot ($53.82 per square meter) or approximately $2 million ($6.05 million in 2011 dollars).[16][67][68]

Restoration and later (1979–)

Prior to restoration, glass and oak partitions and marble wainscot had been removed and the ceilings were suspended.The building Donnell purchased in 1979 had declined badly. The Dearborn entrances had been closed in, the ground floor had been "defaced by garish signs",[69] and the brick had been painted and was peeling. Inside, the marble wainscoting had been painted over and many of the original oak doors had been replaced with cheaper mahogany. The decorative stair rails had been enclosed, and some stairways and corridors had been closed off completely. Much of the original mosaic tile had been demolished—some floors were carpeted, others tiled in vinyl or terrazo. Half of the sixteen elevators were still manually operated.[69] "It was as if it had been partly updated every ten years throughout its history", said Donnell, "it was never done over in its entirety."[66]

Donnell, who had studied architecture at Harvard, planned to gut the building and construct a new, modern office complex inside the historic shell. Failing to obtain financing for the remodeling, he embarked instead on an incremental, "pay as you go"[70] project to restore the Monadnock to its original condition in painstaking detail.[27] The project was, according to historian Donald Miller, the most comprehensive skyscraper restoration ever attempted at the time; it took thirteen years to complete.[71] Working from original drawings discovered at the Art Institute of Chicago, and two old photographs, Donnell and John Vinci, one of the nation's leading preservation architects, restored the building to its condition when first constructed, before any modernizations, working piecemeal as offices became vacant.[72][73]

The color of the shellac was matched to closets where the wood had not been darkened by exposure to light. The mosaic floors were recreated by Italian craftsmen at a cost of $50 per square foot ($538.12 per square meter).[36] A local firm was found that could reproduce the complicated process of sandblasting and hide glue application used to created the original feather chipped glass. This reproduced glass was used to restore the partitions and naturally lit corridors of Root's design.[74] To recreate the doors and wood trim, Donnell purchased the firm that had created the original oak woodwork—and still used the same 19th century machinery.[66] Perfect replicas of the original aluminum light fixtures were fabricated from early photographs and carbon filament light bulbs were obtained to recreate the original lighting effect.[75] A single surviving aluminum staircase was discovered behind a wall, restored, and used as a model to rebuild the lobby stairways and metalwork.[74] The wainscoting on the upper floors was restored with marble salvaged from the recently modernized, nearby 19 LaSalle and Manhattan Buildings.[76] Marble was purchased from the same Italian quarry that supplied Root's original construction to restore the lobby walls and ceilings.[75]

Dearborn street facade in 2008, showing restored granite entryways, entrances to ground floor shops, and fiberglass replicas of original linen window shades

Dearborn street facade in 2008, showing restored granite entryways, entrances to ground floor shops, and fiberglass replicas of original linen window shades

The Dearborn street entrances were reopened and their massive granite lintels and surrounds cleared of layers of black paint or replaced. A source was found for the molded bricks needed to repair or replace the curved corners. Large plate glass windows at the entrance were removed and replaced with double-hung windows that conformed to the original design.[77] Fiberglass shades resembling the original linen versions were installed to preserve the appearance of the facade.[76] The average cost of the restoration work was $1 million per floor ($1.77 million in 2011 dollars) in 1989, or $47 per square foot ($505.92 per square meter).[16][78]

Donnell's goal was that the Monadnock would "not only look as it originally did, it [would] also live as it used to",[79] and he sought tenants for the street-level shops that were similar to their 19th century occupants.[80] Shop windows were cleared of all signs and obstructions to preserve intended view from the corridor through to the street. Fluorescent lighting was prohibited and only gold leaf lettering on the glass was permitted for signage. Shops, all individually owned, were selected to fit the architectural character of the building.[80] A florist, for example, was chosen that evoked a turn-of-the-century atmosphere, as well as a barbershop with vintage fixtures and decor. A tobacconist with oak furnishings, a pen shop with glass cases, a shoe-shine stand, and other service establishments represented, in Donnell's words, "the kind of small-scale entrepreneurs who occupied those spaces at the turn of the century, the kind of people who bring vitality and life to a building because they have a stake in it."[80]

The restoration was a success both critically and commercially. The building was 80 percent occupied when bought in 1979 and rented for $5.50 per square foot ($59.20 per square meter). By 1982, it was 91 percent occupied and commanded rent of $9 per square foot ($96.89 per square meter).[66] The Monadnock was selected as one of top restoration projects in the country by the National Trust for Historic Preservation in 1987, noting "the outstanding quality of the overall restoration effort", and the precision, detail and faithfulness of the interior restoration, in particular the lobby, which "serves as a model for preservation nationwide."[81]

The restored Monadnock is divided into offices of from 250 square feet (23 m2) to 6,000 square feet (560 m2)[81][82] As of 2008, it was 98.9 percent leased; the 300 tenants are primarily independent professional firms and entrepreneurs.[83][84] Rents range from $21 to $23 per square foot ($226 to $247 per square meter), plus electricity.[85]

The building was offered for sale in 2007, with an expected price of $45 to $60 million.[86] A tentative deal was reached at a price of $48 million in 2008.[83]

Architecture

Elevation drawing of typical window bays in the south half. The chamfered brick at the bottom of the window bay is visible in the drawing.

Elevation drawing of typical window bays in the south half. The chamfered brick at the bottom of the window bay is visible in the drawing.

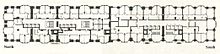

Together, the two parts of the building have a frontage of 420 feet (130 m) on Dearborn Street with a depth of 70 feet (21 m).[87] The original northern half presents a plain, unbroken vertical mass of purple-brown brick, which is contoured to create a gentle curve at the base of the building and an outward flare to form an austere parapet at the top.[88] The gentle swelling at base and cornice, observed historian Donald Hoffman, "came very close to the bell-shaped column the Egyptians had derived from papyrus".[89] The corners of the building are gracefully chamfered as they rise to the top and the oriel windows are chamfered at their base. he floor divisions are not marked on the exterior; the unbroken edifice is interrupted only by a series of cantilevered window bays, separated by rows of single thin silled windows set into the vertical face. The entryways are small, single-height portals topped with plain stone lintels.[88]

The south half preserves the lines and color of the older building, but is vertically divided by a stringcourse over the second story, emphasizing the building's base, and a large ornamental copper cornice at the roof line. Massive blocks of red granite, 6 feet (1.8 m) thick, frame the large, two-story entrances.[27] The projecting window bays of the original are repeated, but alternate in a pattern of two four-window bays to one recessed strip of windows to create the undulating appearance of the facade that was an early trademark of Holabird & Roche.[88][90] Carl Condit, historian of the Chicago school, has commented that:

The general appearance of the Monadnock almost belies its masonry construction. The projecting bays of the walls with their large glass areas give the structure a light and open appearance in spite of its great mass.... Stripped of every vestige of ornament, its rigorous geometry softened only by the slight inward curve of the wall at the top of the first story, the outward flare of the parapet, and the progressive rounding of the corners from bottom to top, subtly proportioned and scaled, the Monadnock is a severe yet powerfully expressive composition in horizontal and vertical lines.[91]The Monadnock rests on the floating foundation system invented by Root for the Montauk Building that revolutionized the way tall buildings were built on Chicago's spongy soil.[92] A 2-foot (0.61 m) layer of concrete, reinforced with steel beams, forms a spread footing extending out 11 feet (3.4 m) under the surrounding streets, spreading the weight of the building over a large area of earth.[93] The building was designed to settle 8 inches (200 mm), but by 1905 had settled that much and "several inches more",[18] necessitating reconstruction of the first floor.[69] By 1948, it had settled 20 inches (51 cm), resulting in a step down from the street to the ground floor.[93][94] The entire east wall is supported on caissons sunk to the hardpan, installed when the subway Blue Line was dug under Dearborn Street in 1940.[95]

The narrow building allows an external exposure to all of the 300 offices, which pass natural light via double hung outside windows through feather-chipped glass transoms and hallway partitions into the single central corridor. Skylights bring sunlight into the open stairwells.[96] The north half corridors are 20 feet (6.1 m) wide and the south half corridors are 11 feet 6 inches (3.51 m). In the north half, there are two open stairs in the center at the one third points, with perforated risers, white marble treads, and decorative steel railings. There are two banks of four elevators on the west side of the corridor, one for passengers and the other for freight.[94] In the south half, there is a single bank of elevators on the north half of the length. The southern bank was abandoned and slabbed over on each floor.[69] There is a flight of stairs behind each of these shafts with marble treads, closed cast iron risers, and ornamental balusters.[94] The basic office suite is 600 square feet (56 m2), consisting of one outer office and two or more inner offices.[97] Heavy internal walls at the quarter and halfway points, the arches of which manifest Root's innovative wind bracing, mark the boundaries of the four original buildings.[69]

Surrounding area

The Printer's Row North Historic District and Library-State/Van Buren 'L' station. The Monadnock is at the left, in front of the Fisher Building and the red CNA Center. The Old Colony Building is on the right.

The Printer's Row North Historic District and Library-State/Van Buren 'L' station. The Monadnock is at the left, in front of the Fisher Building and the red CNA Center. The Old Colony Building is on the right.

The Monadnock belongs to the Printing House Row District, a National Historic Landmark which includes the Manhattan Building, the Old Colony Building, and the Fisher Building, some of Chicago's seminal early skyscrapers.[98] The Manhattan Building, built by William LeBaron Jenney in 1890, was the first building in Chicago with a complete steel skeleton or "Chicago" construction, an innovation Jenney had introduced in the Home Insurance Building in 1884.[99] The first 16-story building in America, at the time it was "regarded with awe and fear".[100] Jenny's masterpiece, the Manhattan was considered a technical triumph in construction.[101] The 17-story Old Colony, built by Holabird & Roche in 1894, was considered one of the structural masterpieces of its time for its revolutionary portal form of bracing.[102] It is the only survivor of a group of Chicago school buildings with rounded corner bays.[103] The Fisher Building, built by Burnham in 1894, was an engineering miracle—the first tall commercial building to be built almost entirely without bricks. Its steel frame and thin terracotta curtain wall allowed two-thirds of the surface to be covered with glass.[104]

The district overlaps geographically with the Printer's Row neighborhood, originally the center of Chicago's printing and publishing industry, but now mostly converted to residential housing.[105] The area is also home to the largest public library in the world, the Harold Washington Library, named for Chicago's first African-American mayor, and the Loop campus of Depaul University, America's largest Roman Catholic university.[106][107]

Immediately to the west on Jackson Street is the Union League Club of Chicago, founded in 1879 as a civic organization for "upright, law-abiding businessmen".[108] To the north are the three buildings comprising Ludwig Mies Van der Rohe's minimalist Federal Plaza: the 1964 Everett McKinley Dirksen United States Courthouse, the only courthouse designed by Mies; the 1973 United States Post Office Loop Station; and the 1975 Kluczynski Federal Building, Mies's last project, considered to mark the apex of his career.[109][110] The triangular, 27-story Metropolitan Correctional Center, a detention center serving the Federal courts in the Dirksen Building and nearby Ralph H. Metcalfe Federal Building, is southwest of the Monadnock at Clark and LaSalle.[111]

The south leg of the Chicago Transit Authority elevated rail loop runs next to the building on Van Buren Street; the CTA's Brown, Orange, Pink, and Purple Lines are served by the Library-State/Van Buren stop one block to the east. The Jackson street subway station, serving the Blue Line, is on the Dearborn Street side of the building.[112]

Critical reception and historical significance

Contemporary Chicago critics considered the building too radical a departure from Burnham & Root's previous designs and too extreme in its stark simplicity and disregard for prevailing aesthetic norms, calling it an "engineer's house"[113] and a "thoroughly puritanical"[114] example of commercial style.[115] European critics were even less approving. In the words of French architect Jacques Hermant, "The Monadnock was no longer the result of an artist responding to particular needs with intelligence and drawing from them all of the possible consequences. It is the work of a laborer who, without the slightest study, super-imposes 15 strictly identical stories to make a block then stops when he finds the block high enough."[116]

Other critics saw this lack of style as "natural" and what made the Monadnock truly modern. New York critic Barr Feree wrote in 1892 that "There are no attempts at facades ... no ornamental appendages, nothing but a succession of windows, frankly stating that the structure is an office building, devoted to business, needing and using every available surface."[117] Other critics praised the truthfulness of the building to the ideals of business, which, while "not necessarily the highest to which we might aspire to in art ... are the only ideals the business building ought to express".[117] Montgomery Schuyler, one of the Monadnock's most enthusiastic defenders, argued that the Monadnock's lack of ornament was not a lack of art, but rather "radiated the gravity of modern business life".[117]

The Monadnock was widely praised by early twentieth-century German architects, including Mies, who on his arrival in Chicago in 1938 declared that "The Monadnock block is of such vigor and force that I am at once proud and happy to make my home here."[118] These European architects found the building's attention to purpose and functional expression inspiring. Bauhaus architect Ludwig Hilberseimer wrote that "The false solution—unfortunately too common—of applying meaningless and misplaced adornment is here instinctively avoided. An innate feeling for proportion gives this great building inner consistency and logical purity."[118]

Modern critics have praised the Monadnock as one of the most important exemplars of the Chicago school, along with Louis Sullivan's Carson, Pirie, Scott and Company Building.[66] It has been called "a triumph of unified design"[119] comparable to Henry Hobson Richardson's Marshall Field's Wholesale Store, and "one of the most exciting aesthetic experiences our commercial architecture has ever produced".[120]

The building was one of the first five selected by the Chicago Commission on Architectural Landmarks in 1958, "in recognition of its original design and its historical interest as the highest wall-bearing structure in Chicago".[30][121] The commission went on to note that the "restrained use of brick, soaring massive walls, omission of ornamental forms, unite in a building simple yet majestic."[30] In 1973, the Chicago City Council voted unanimously to designate the Monadnock a Chicago Landmark, stating that "The two halves of this building provide a unique perspective for examining the history and development of modern architecture.... Together, they mark the end of one building tradition and the beginning of another."[2][122]i[›] Critics of the Monadnock's landmark status objected that it would prevent the necessary demolition of the building, which was "an excellent example of a building that is ... no longer fulfilling the functions it was designed to fulfill" and "a wasting asset" that underperformed the market and was far less valuable than the land on which it stood would be.[123]

The National Register of Historic Places, to which the Monadnock was added in 1970, noted that "the sheer, unadorned walls of this building forming a powerful mass became, prophetically, a forerunner of the 'slab skyscraper'—a style not popular until the late 1920's" and that "the two sections ... make, as an ensemble, one of the strongest, yet refined architectural statements in the development of twentieth century architecture."[3][124] Its nomination as a National Historic Landmark in 1976, as part of the South Dearborn Street-Printing House Row Historic District, included the comment that it was "one of the most classical statements ever made in the skyscraper idiom."[93]

Notes

^ a: The other was William E. Hale, who introduced the hydraulic elevator to Chicago in 1878.[125]

^ b: When completed, the Monadnock was the tallest commercial masonry building in the world and, as of 2000, it remained so.[126]

^ c: The Monadnock used a portal-strut system, which braced the masonry piers with iron girders. This evolved into what would come to be known as the portal system, using solid web plates instead, first used by Holabird & Roche in the Old Colony Building in 1894.[127]

^ d: Feather chipping creates a frosted texture on plate glass using a technique called glue chipping, in which the glass is sandblasted to roughen the surface and then painted with animal hide glue which is fan dried at a carefully controlled temperature to shrink the glue, creating a surface of feather-like chips in the glass.

^ e: The Washington Monument was fitted with a 100-ounce (2.8 kg) cast aluminum cap in 1884, arguably the first architectural use of aluminum. The Monadnock represents the first use of aluminum as a functional element of building construction.[128]

^ f: The Monadnock had two (and later four) names because it was legally four separate buildings—the Monadnock, the Kearsage, the Katahdin, and the Wachusett—each owned by a different branch of the Brooks family that could sell their share independently. The other names were abandoned in the late 1890s and the four-way ownership was dissolved in the early 1920s. The letters M, K, and W can still be found on the original cast iron doorknobs, indicating which building each office originally was in.[129]

^ g: Holabird & Roche moved their offices to the north half of the Monadnock in 1892, while the south half was under construction. They remained there until 1910, and built no fewer than five major projects for the Brooks brothers, practically at the same time, all within blocks of the Monadnock.[130]

^ h: The Van Buren street side was designed to be the main entrance. When the 'L' tracks were erected literally on the doorstep of the building, the configuration was reversed to make Jackson street the building's "front".[26]

^ i: The original Commission on Architectural Landmarks was advisory in nature and was ultimately unsuccessful in protecting Chicago's landmark buildings. Beginning in 1968, Chicago Landmark status was granted by statute, which prohibited the destruction or drastic alteration of designated buildings without approval from the city.[131]References

- ^ National Park Service 1976.

- ^ a b City of Chicago 1973.

- ^ a b National Park Service 1970.

- ^ Pitts 1975, p. 3.

- ^ Miller 1997, p. 320.

- ^ Berger 1992, p. 34.

- ^ Miller 1997, p. 319.

- ^ Douglas 2004, p. 19.

- ^ Berger 1992, p. 39.

- ^ Hines 2008, p. 17.

- ^ Merwood-Salisbury 2009, p. 18.

- ^ Miller 1997, pp. 319, 326.

- ^ Merwood-Salisbury 2009, p. 16.

- ^ Berger 1992, p. 44.

- ^ Merwood-Salisbury 2009, pp. 20,58.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis.

- ^ a b c d e Merwood-Salisbury 2009, p. 58.

- ^ a b Randall 1999, p. 141.

- ^ Hoffman 1973, p. 156.

- ^ Commission on Chicago Historical and Architectural Landmarks 1976, p. 3.

- ^ a b Condit 1973, p. 66.

- ^ a b Condit 1973, p. 67.

- ^ Sinkevitch 2004, pp. 63–64.

- ^ a b c Commission on Chicago Historical and Architectural Landmarks 1972, p. 8.

- ^ American Architect 1892, p. 134.

- ^ a b c d Fuller 1958, p. B5.

- ^ a b c Miller 1991, p. 147.

- ^ Keohan 1989, p. 6.

- ^ National Park Service 1992, p. 85.

- ^ a b c Overby & Homolka 1963, p. 2.

- ^ Sinkevitch 2004, p. 469.

- ^ Monroe 1896, p. 141.

- ^ Hoffman 1973, p. 155.

- ^ Plumbe 1893, p. 383.

- ^ Chicago Daily Tribune April 1893, p. 30.

- ^ a b Clarke, Saliga & Zukowsky 1990, pp. 41–42.

- ^ Hoffman 1973, p. 165.

- ^ Commission on Chicago Historical and Architectural Landmarks 1972, p. 3.

- ^ Chicago Daily Tribune January 1893, p. 28.

- ^ Condit 1973, p. 119.

- ^ a b Commission on Chicago Historical and Architectural Landmarks 1972, p. 4.

- ^ Merwood-Salisbury 2009, p. 60.

- ^ Bruegmann 1997, p. 472.

- ^ a b Rand McNally 1898, p. 24.

- ^ Chicago Daily Tribune 1892, p. 28.

- ^ Kerch 1991.

- ^ Plumbe 1893, p. 3.

- ^ Chicago Daily Tribune 1896, p. 3.

- ^ Chicago Daily Tribune 1900, p. 49.

- ^ Chicago Daily News January 1893, p. 383.

- ^ Keohan 1989, p. 1.

- ^ Rand McNally 1898, p. 22.

- ^ Berger 1992, p. 45.

- ^ Borzo 2007, pp. 54–55.

- ^ Chicago Daily Tribune 1901, p. A5.

- ^ Chicago Daily Tribune 1903, p. 8.

- ^ Aldis v. Union Elevated R. Co. 1903.

- ^ New York Times 1903.

- ^ a b c Architectural Forum 1938, p. 307.

- ^ a b c Chase 1938, p. C12.

- ^ Chicago Daily Tribune 1938, p. C14.

- ^ a b Nagelberg 1967, p. D3.

- ^ Nagelberg 1966, p. C5.

- ^ Chicago Tribune 1966, p. C5.

- ^ a b Storch & Branegan 1979, p. E7.

- ^ a b c d e f Washburn 1982, p. N_B1.

- ^ Chicago Tribune 1979, p. E8.

- ^ Keohan 1989, p. 5.

- ^ a b c d e Weese 1978, p. 90.

- ^ Newman 1991.

- ^ Miller 1991, pp. 140–141.

- ^ Chicago Tribune October 1987, p. 2D.

- ^ Miller 1991, pp. 145,147.

- ^ a b Clarke 1985, p. 22.

- ^ a b Miller 1991, p. 145.

- ^ a b Clarke 1985, p. 23.

- ^ Reuel 1986, p. 22.

- ^ Keohan 1989, p. 8.

- ^ Miller 1991, p. 140.

- ^ a b c Walsh 1987, p. 52.

- ^ a b Chicago Tribune 1987.

- ^ Monadnock Building 2010a.

- ^ a b Corfman 2008.

- ^ Monadnock Building 2010b.

- ^ Monadnock Building 2010c.

- ^ Baeb & Corfman 2007.

- ^ Randall 1999, p. 185.

- ^ a b c Merwood-Salisbury 2009, pp. 59–60.

- ^ Hoffman 1973, p. 174.

- ^ Clarke, Saliga & Zukowsky 1990, pp. 42.

- ^ Condit 1973, p. 68.

- ^ Miller 1997, p. 374.

- ^ a b c Pitts 1976, p. 29.

- ^ a b c Weese 1978, p. 89.

- ^ Randall 1999, p. 142.

- ^ Keohan 1989, p. 2.

- ^ Keohan 1989, p. 3.

- ^ Pitts 1976, p. 3.

- ^ Pitts 1976, p. 13.

- ^ Rand McNally 1898, p. 80.

- ^ Pitts 1976, p. 9.

- ^ Pitts 1976, p. 16.

- ^ Sinkevitch 2004, p. 62.

- ^ Pitts 1976, p. 24.

- ^ Solomon 2010.

- ^ Frommers 2009.

- ^ Chicago Tribune 2010.

- ^ Union League Club of Chicago 2006.

- ^ O'Gorman 2003, p. 27.

- ^ Siegel 1970, p. 212.

- ^ Sinkevitch 2004, pp. 74–75.

- ^ Chicago Transit Authority 2010.

- ^ Hotchkiss 1891, p. 70.

- ^ Hotchkiss 1891, p. 170.

- ^ Bruegmann 1997, p. 120.

- ^ Merwood-Salisbury 2009, p. 46.

- ^ a b c Merwood-Salisbury 2009, p. 63.

- ^ a b Merwood-Salisbury 2009, p. 136.

- ^ Burchard & Bush-Brown 1967, p. 251.

- ^ Condit 1973, p. 69.

- ^ Chicago Daily Tribune 1958, p. B6.

- ^ Ziemba 1973, p. W4.

- ^ Washburn 1974, p. B1.

- ^ Pitts 1970, pp. 29–30.

- ^ Miller 1997, p. 311.

- ^ Wiseman 2000, p. 56.

- ^ Freitag 1895, pp. 151–152.

- ^ National Park Service 1992, p. 84.

- ^ Merwood-Salisbury 2009, pp. 159–160.

- ^ Bruegmann 1997, pp. 38,40.

- ^ Chicago Tribune 1968, p. B10.

Works cited

- Aldis v. Union Elevated R. Co., 68 N.E. 95 (Supreme Court of Illinois 1903).

- American Architect (1892–02–27). "Chicago". American Architect and Building News 35 (822). OCLC 1479311.

- Architectural Forum (October 1938). "Chicago Remodels a Landmark". Architectural Forum: 308–310. ISSN 0003-8539.

- Baeb, Eddie; Corfman, Thomas A. (2007–05–07). "Monadock for sale". Crain's Chicago Business. http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1G1-163311203.html. Retrieved 2010–10–20.

- Berger, Miles L. (1992). They Built Chicago: Entrepreneurs Who Shaped a Great City's Architecture. Chicago: Bonus Books. ISBN 0-929387-76-7.

- Borzo, Greg (2007). The Chicago 'L'. Charleston, S.C.: Arcadia Pub.. ISBN 0-7385-5100-7.

- Bruegmann, Robert (1997). The Architects and the City: Holabird & Roche of Chicago, 1880–1910. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-07695-4.

- Burchard, John; Bush-Brown, Albert (1967). The Architecture of America: A Social and Cultural History. London: V. Gollancz. OCLC 150479726.

- Chase, Al (1938–01–16). "Interior of 45 Year Old Block to be Rebuilt" (fee required). Chicago Daily Tribune. http://proquest.umi.com/pqdweb?did=493197732&sid=2&Fmt=10&clientId=11417&RQT=309&VName=HNP. Retrieved 2010–10–20.

- Chicago Daily Tribune (1893–01–01). "Chicago's Great Buildings" (fee required). Chicago Daily Tribune. http://pqasb.pqarchiver.com/chicagotribune/access/432301132.html?FMT=ABS&FMTS=ABS:AI&type=historic&date=Jan+01%2C+1893&author=&pub=Chicago+Tribune&desc=CHICAGO%27S+GREAT+BUILDINGS.. Retrieved 2010–10–20.

- Chicago Daily Tribune (1893–04–23). "Ownership of the Monadnock" (fee required). Chicago Daily Tribune. http://pqasb.pqarchiver.com/chicagotribune/access/432512492.html?dids=432512492:432512492&FMT=CITE&FMTS=CITE:AI&type=historic&date=Apr+23%2C+1893&author=&pub=Chicago+Tribune&desc=OWNERSHIP+OF+THE+MONADNOCK.. Retrieved 2010–10–20.

- Chicago Daily Tribune (1896–02–24). "Tale of a Skyscraper" (fee required). Chicago Daily Tribune. http://pqasb.pqarchiver.com/chicagotribune/access/428346231.html?FMT=ABS&FMTS=ABS:AI&type=historic&date=Feb+24%2C+1896&author=&pub=Chicago+Tribune&desc=TALE+OF+A+SKYSCRAPER.. Retrieved 2010–10–20.

- Chicago Daily Tribune (1900–07–08). "Most Remarkable Postal District in the World" (fee required). Chicago Daily Tribune. http://pqasb.pqarchiver.com/chicagotribune/access422065881.html?FMT=ABS&FMTS=ABS:AI&type=historic&date=Jul+08%2C+1900&author=&pub=Chicago+Tribune&desc=Most+Remarkable+Postal+District+in+the+World. Retrieved 2010–10–20.

- Chicago Daily Tribune (1901–01–06). "'L' Roads Win in Damage Suit" (fee required). Chicago Daily Tribune. http://pqasb.pqarchiver.com/chicagotribune/access/425602831.html?FMT=ABS&FMTS=ABS:AI&type=historic&date=Jan+06%2C+1901&author=&pub=Chicago+Tribune&desc=%22+L+%22+ROADS+WIN+IN+DAMAGE+SUITS.. Retrieved 2010–10–20.

- Chicago Daily Tribune (1903–04–26). "Court Hits 'L' Roads" (fee required). Chicago Daily Tribune. http://pqasb.pqarchiver.com/chicagotribune/access/407128521.html?FMT=ABS&FMTS=ABS:AI&type=historic&date=Apr+26%2C+1903&author=&pub=Chicago+Tribune&desc=COURT+HITS+%22L%22+ROADS.. Retrieved 2010–10–20.

- Chicago Daily Tribune (1938–11–6). "Monadnock Gets 35 New Tenants After Restyling" (fee required). Chicago Daily Tribune. http://pqasb.pqarchiver.com/chicagotribune/access/493457892.html?FMT=AI&FMTS=AI:CITE&type=historic&date=Nov+06%2C+1938&author=&pub=Chicago+Tribune&desc=MONADNOCK+GETS+35+NEW+TENANTS+AFTER+RESTYLING. Retrieved 2010–12–8.

- Chicago Daily Tribune (1958–05–07). "Pick 4 Loop Buildings as Landmarks" (fee required). Chicago Daily Tribune. http://pqasb.pqarchiver.com/chicagotribune/access/519378232.html?dids=519378232:519378232&FMT=ABS&FMTS=ABS:AI&type=historic&date=May+07%2C+1958&author=&pub=Chicago+Tribune&desc=PICK+4+LOOP+BUILDINGS+AS+LANDMARKS&pqatl=google. Retrieved 2010–11–01.

- Chicago Transit Authority (2010). Downtown Transit Sightseeing Guide (Map). http://www.transitchicago.com/asset.aspx?AssetId=181. Retrieved 2010–11–26.

- Chicago Tribune (1966–04–26). "Monadnock Building Takes on Bright Look" (fee required). Chicago Tribune. http://pqasb.pqarchiver.com/chicagotribune/access/595818212.html?FMT=CITE&FMTS=AI:CITE&type=historic&date=Apr+24%2C+1966&author=&pub=Chicago+Tribune&desc=Monadnock+Building+Takes+on+Bright+Look. Retrieved 2010–10–20.

- Chicago Tribune (1968–04–18). "Landmark Commission Reactivated" (fee required). Chicago Tribune. http://pqasb.pqarchiver.com/chicagotribune/access/624604262.html?dids=624604262:624604262&FMT=CITE&FMTS=CITE:AI&type=historic&date=Apr+18%2C+1968&author=&pub=Chicago+Tribune&desc=Landmark+Commission+Reactivated&pqatl=google. Retrieved 2010–11–01.

- Chicago Tribune (1979–06–01). "Monadnock Sold, Default Averted" (fee required). Chicago Tribune. http://pqasb.pqarchiver.com/chicagotribune/access/625988692.html?FMT=CITE&FMTS=AI:CITE&type=historic&date=Jun+01%2C+1979&author=&pub=Chicago+Tribune&desc=Monadnock+sold%2C+default+averted. Retrieved 2010–10–20.

- Chicago Tribune (1987–10–25). "Monadnock Building Preservation Honored" (fee required). Chicago Tribune: p. 2.G. http://pqasb.pqarchiver.com/chicagotribune/access/24850517.html?FMT=FT&FMTS=ABS:FT&type=current&date=Oct+25%2C+1987&author=&pub=Chicago+Tribune+(pre-1997+Fulltext)&desc=MONADNOCK+BUILDING+PRESERVATION+HONORED. Retrieved 2011–01–04.

- Chicago Tribune (2010–11–10). "DePaul University". Chicago Tribune. http://www.chicagotribune.com/topic/education/depaul-university-OREDU000019.topic. Retrieved 2011–01–06.

- City of Chicago (1973–11–14). "Monadnock Block". Chicago Landmarks. City of Chicago. Archived from the original on 2008–05–13. http://web.archive.org/web/20080611140249/webapps.cityofchicago.org/LandmarksWeb/landmarkDetail.do;jsessionid=LPHQf189zpplmzX2L0w7qc6Tw0l93Vsh0VvvzxPS0QzVTKHJypVR!-1338180875?lanID=1373. Retrieved 2010–12–06.

- Clarke, Jane (January/February 1985). "A Man and His Mountain: Restoring the Monadnock". Inland Architect 29 (1): 20–23. ISSN 0020-1472.

- Clarke, Jane; Saliga, Pauline A.; Zukowsky, John (1990). The Sky's the Limit: A Century of Chicago Skyscrapers. New York: Rizzoli International. ISBN 0-8478-2104-8.

- Commission on Chicago Historical and Architectural Landmarks (1972). A Summary of Information on the South Half of the Monadnock Block. Chicago: The Commission. OCLC 6405161.

- Commission on Chicago Historical and Architectural Landmarks (1976). Monadnock Block. Chicago: The Commission. OCLC 4675569.

- Condit, Carl W. (1973). The Chicago School of Architecture: A History of Commercial and Public Building in the Chicago Area, 1875–1925. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. OCLC 1112620.

- Corfman, Thomas A. (2008–04–02). "Firm has tentative deal to buy Monadnock". Chicago Real Estate Daily. http://www.chicagorealestatedaily.com/article/20080402/CRED03/200028809/firm-has-tentative-deal-to-buy-monadnock. Retrieved 2010–10–20.

- Douglas, George H. (2004). Skyscrapers: A Social History of the Very Tall Building in America. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Co.. ISBN 0-7864-2030-8.

- Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (Estimate) 1800–2008". Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. http://www.minneapolisfed.org/community_education/teacher/calc/hist1800.cfm. Retrieved 2010–12–7.

- Freitag, Joseph K. (1895). Architectural Engineering: With Special Reference to High Building Construction, Including Many Examples Of Chicago Office Buildings (1st ed.). New York: J. Wiley & Sons. OCLC 3920336.

- Frommers (2009). "Chicago Public Library/Harold Washington Library Center". Frommers. http://www.frommers.com/destinations/chicago/A19396.html. Retrieved 2010–10–27.

- Fuller, Ernest (1958–12–06). "Famous Chicago Buildings" (fee required). Chicago Daily Tribune. http://proquest.umi.com/pqdweb?did=569501622&sid=1&Fmt=10&clientId=11417&RQT=309&VName=HNP. Retrieved 2010–10–20.

- Hines, Thomas S. (2008). Burnham of Chicago: Architect and Planner (2nd ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-34172-0.

- Hoffman, Donald (1973). The Architecture of John Wellborn Root. Johns Hopkins Studies in Nineteenth-Century Architecture, 19. Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-1371-9.

- Hotchkiss, George Woodward, ed (1891). Industrial Chicago. 1. Chicago: Goodspeed Pub. Co.. OCLC 144605167.

- Keohan, Thomas G. (July 1989). "Historic Interior Spaces No. 2: Preserving Historic Office Building Corridors". Preservation Tech Notes (Washington, D.C.: National Park Service). ISSN 0741-9023.

- Kerch, Steve (1991–04–03). "Time Travel: For Monadnock`s Small-Tenant Niche, The Past is the Present and Future". Chicago Tribune. http://articles.chicagotribune.com/1991-04-03/business/9101300828_1_tenants-building-roster-chicago-architecture-foundation. Retrieved 2010–10–22.

- Merwood-Salisbury, Joanna (2009). Chicago 1980: The Skyscraper and the Modern City. Chicago Architecture and Urbanism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-52078-1.

- Miller, Donald L. (March 1991). "One Fine Building and a Few Good Men". Chicago Magazine: 140–147. ISSN 0362-4595.

- Miller, Donald L. (1997). City of the Century: The Epic of Chicago and the Making of America (1st trade paperback ed.). New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-83138-4.

- Monadnock Building (2010a). "Building". http://www.monadnockbuilding.com/building.htm. Retrieved 2010–11–01.

- Monadnock Building (2010b). "Monadnock". http://www.monadnockbuilding.com/. Retrieved 2010–11–01.

- Monadnock Building (2010c). "Leasing". http://www.monadnockbuilding.com/leasing.htm. Retrieved 2010–11–01.

- Monroe, Harriet (1896). John Wellborn Root: A Study of his Life and Work. New York: Houghton, Mifflin. OCLC 2014414.

- Nagelberg, Alvin (1966–08–24). "Monadnock Building, Loop Landmark, Sold" (fee required). Chicago Tribune. http://pqasb.pqarchiver.com/chicagotribune/access/584473332.html?FMT=ABS&FMTS=ABS:AI&type=historic&date=Aug+24%2C+1966&author=&pub=Chicago+Tribune&desc=Monadnock+Building%2C+Loop+Landmark%2C+Sold. Retrieved 2010–10–20.

- Nagelberg, Alvin (1967–06–14). "Monadnock Building Found to Be Sinking" (fee required). Chicago Tribune. http://pqasb.pqarchiver.com/chicagotribune/access/595213152.html?FMT=ABS&FMTS=ABS:AI&type=historic&date=Jun+14%2C+1967&author=&pub=Chicago+Tribune&desc=Monadnock+Building+Found+to+Be+Sinking. Retrieved 2010–10–20.

- National Park Service (1970–11–20). "Monadnock Block". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. http://nrhp.focus.nps.gov/natreghome.do?searchtype=natreghome. Retrieved 2010–09–29.

- National Park Service (1976–01–07). "South Dearborn Street—Printing House Row North Historic District". National Historic Landmark Summary Listing. National Park Service. http://tps.cr.nps.gov/nhl/detail.cfm?ResourceId=1618&ResourceType=District. Retrieved 2010–09–29.

- National Park Service (1992). Metals in America's Historic Buildings: Uses and Preservation Treatments (2nd ed.). National Park Service. ISBN 0-16-061655-7.

- New York Times (1903–04–26). "Decide Against Elevated". New York Times. http://query.nytimes.com/mem/archive-free/pdf?res=F5081EFF345412738DDDAF0A94DC405B838CF1D3. Retrieved 2010–10–20.

- O'Gorman, Thomas J. (2003). Architecture in Detail Chicago. New York: PRC Publishing. ISBN 1-85648-668-0.

- Newman, M. W. (1991–11–11). "At 100, Monadnock Gladly Shows its Age". Chicago Sun-Times. http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1P2-4081991.html.

- Overby, Osmund R.; Homolka, Larry J. (1963). "Monadnock Block". Historic American Buildings Survey (Library of Congress). http://loc.gov/pictures/item/il0049/.

- Pitts, Carolyn (1970–11–20). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination: Monadnock Building" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places Inventory (National Park Service): 28–31. http://pdfhost.focus.nps.gov/docs/NHLS/Text/76000705.pdf.

- Pitts, Carolyn (1975–07–25). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination: South Dearborn Street—Printing House Row Historic District" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places Inventory (National Park Service). http://gis.hpa.state.il.us/hargis/PDFs/200727.pdf.

- Pitts, Carolyn (1976–01–07). "National Historic Landmark Nomination: South Dearborn Street—Printing House Row Historic District" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places Inventory (National Park Service). http://pdfhost.focus.nps.gov/docs/NHLS/Text/76000705.pdf.

- Plumbe, George, ed (1893). The Daily News Almanac and Political Register. 9. Chicago: Chicago Daily News Company. OCLC 1696012.

- Rand McNally (1898). Bird's-Eye Views and Guide to Chicago. Chicago: Rand McNally. OCLC 26177999.

- Randall, Frank A. (1999). History of the Development of Building Construction in Chicago (2nd revised and expanded ed.). Urbana: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-02416-8.

- Reuel, Henri (1986). "Landmark Chicago". Chicago Architectural Annual: 19–23. ISSN 0885-2359.

- Siegel, Arthur, ed (1970). Chicago's Famous Buildings: A Photographic Guide to the City's Architectural Landmarks and Other Notable Buildings (2nd revised and enlarged ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-75685-8.

- Sinkevitch, Alice, ed (2004). AIA Guide to Chicago (2nd ed.). Orlando, Fla: Harcourt. ISBN 0-15-602908-1.

- Solomon, Alan (2010). "Printers Row: One-Time Printing District Becomes a Popular Residential Area". Explore Chicago. City of Chicago. http://www.explorechicago.org/city/en/neighborhoods/printers_row.html. Retrieved 2010–10–27.

- Storch, Charles; Branegan, Jay (1979–03–09). "Monadnock Building Foreclosure Suit Filed" (fee required). Chicago Tribune. http://pqasb.pqarchiver.com/chicagotribune/access/615067962.html?FMT=ABS&FMTS=ABS:AI&type=historic&date=Mar+09%2C+1979&author=&pub=Chicago+Tribune&desc=Monadnock+Building+foreclosure+suit+filed. Retrieved 2010–10–20.

- Union League Club of Chicago (2006). "History". Union League Club of Chicago. http://www.ulcc.org/Default.aspx?p=DynamicModule&pageid=309759&ssid=198317&vnf=1. Retrieved 2010–11–15.

- Walsh, Michael (May/June 1987). "Evolving Design". Inland Architect 31 (3): 51–53. ISSN 0020-1472.

- Washburn, Gary (1974–02–24). "Landmark Battle Isn't Good vs. Bad, Developers Say" (fee required). Chicago Tribune. http://pqasb.pqarchiver.com/chicagotribune/access/633170812.html?FMT=ABS&FMTS=ABS:AI&type=historic&date=Feb+24%2C+1974&author=&pub=Chicago+Tribune&desc=Landmark+battle+isn%27t+good+vs.+bad%2C+developers+say. Retrieved 2010–10–20.

- Washburn, Gary (1982–08–15). "Tight Money a Parent of Renewal" (fee required). Chicago Tribune. http://pqasb.pqarchiver.com/chicagotribune/access/628693802.html?FMT=ABS&FMTS=ABS:AI&type=historic&date=Aug+15%2C+1982&author=&pub=Chicago+Tribune&desc=Tight+money+a+parent+of+renewal. Retrieved 2010–10–20.

- Weese, Harry (1978). Four Landmark Buildings in Chicago's Loop: A Study of Historic Conservation Options. Washington, DC: Heritage Conservation and Recreation Service, Department of the Interior. OCLC 5279878.

- Wiseman, Carter (2000). Twentieth-Century American Architecture: The Buildings and their Makers. New York: Norton. ISBN 0-393-32054-5.

- Ziemba, Stan (1973–03–22). "Monadnock Cited for Architecture" (fee required). Chicago Tribune. http://pqasb.pqarchiver.com/chicagotribune/access/598497002.html?FMT=ABS&FMTS=ABS:AI&type=historic&date=Mar+22%2C+1973&author=&pub=Chicago+Tribune&desc=Monadnock+cited+for+architecture. Retrieved 2010–10–20.

External links

Media related to Monadnock Building, Chicago at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Monadnock Building, Chicago at Wikimedia CommonsU.S. National Register of Historic Places Topics Lists by states Alabama • Alaska • Arizona • Arkansas • California • Colorado • Connecticut • Delaware • Florida • Georgia • Hawaii • Idaho • Illinois • Indiana • Iowa • Kansas • Kentucky • Louisiana • Maine • Maryland • Massachusetts • Michigan • Minnesota • Mississippi • Missouri • Montana • Nebraska • Nevada • New Hampshire • New Jersey • New Mexico • New York • North Carolina • North Dakota • Ohio • Oklahoma • Oregon • Pennsylvania • Rhode Island • South Carolina • South Dakota • Tennessee • Texas • Utah • Vermont • Virginia • Washington • West Virginia • Wisconsin • WyomingLists by territories Lists by associated states Other City of Chicago Architecture · Beaches · Climate · Colleges and Universities · Community areas · Culture · Demographics · Economy · Flag · Freeways · Geography · Government · History · Landmarks · Literature · Media · Music · Neighborhoods · Parks · Public schools · Skyscrapers · Sports · Theatre · Transportation

Category ·

Category ·  Portal

PortalChicago Landmark skyscrapers National Historic Landmark,

National Register of Historic Places,

Chicago LandmarkNational Register of Historic Places,

Chicago LandmarkChicago Landmark 330 North Wabash · 333 North Michigan · 35 East Wacker · Allerton Hotel · Brooks Building · Bryn Mawr Apartment Hotel · Carbide & Carbon Building · Chicago Building · Civic Opera House · Heyworth Building · Inland Steel Building · London Guarantee Building · Mather Tower · New York Life Insurance Building · Old Dearborn Bank Building · Palmer House · Powhatan Apartments · Pittsfield Building · Richard J. Daley Center · Tribune Tower

See Also Apartments · Culture · Education · Historic Districts · Houses · Memorials and Monuments · Municipal · Skyscrapers · Transportation · WorshipCategories:- Historic district contributing properties

- Buildings and structures in Chicago, Illinois

- Chicago school (architecture)

- Landmarks in Chicago, Illinois

- National Register of Historic Places in Chicago, Illinois

- Office buildings in Chicago, Illinois

- Skyscrapers in Chicago, Illinois

- Buildings and structures completed in 1891

- Buildings and structures completed in 1893

- Burnham and Root buildings

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.