- Matthew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act

-

The Matthew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act, also known as the Matthew Shepard Act, is an American Act of Congress, passed on October 22, 2009,[1] and signed into law by President Barack Obama on October 28, 2009,[2] as a rider to the National Defense Authorization Act for 2010 (H.R. 2647). Conceived as a response to the murders of Matthew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr., the measure expands the 1969 United States federal hate-crime law to include crimes motivated by a victim's actual or perceived gender, sexual orientation, gender identity, or disability.[3]

The bill also:

- removes the prerequisite that the victim be engaging in a federally-protected activity, like voting or going to school;

- gives federal authorities greater ability to engage in hate crimes investigations that local authorities choose not to pursue;

- provides $5 million per year in funding for fiscal years 2010 through 2012 to help state and local agencies pay for investigating and prosecuting hate crimes;

- requires the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) to track statistics on hate crimes based on gender and gender identity (statistics for the other groups were already tracked). [4][5]

The Act is the first federal law to extend legal protections to transgender persons.[6]

Contents

Origin

The Act is named after two victims of bias-motivated crimes in the United States, Matthew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr.[7] Matthew Shepard was a student who was tortured and murdered in 1998 near Laramie, Wyoming because he was perceived to be homosexual.[7] James Byrd, Jr. was an African-American man who was tied to a truck by two known white supremacists, dragged from it, and decapitated in Jasper, Texas in 1998.[7]

Matthew Shepard's killers were given life sentences in Wyoming—in large part because his parents sought mercy for his killers. Two of James Byrd's murderers were sentenced to death, while the third was sentenced to life in prison. These convictions were obtained without the assistance of hate crimes laws, since none was applicable at the time.

The murders and subsequent trials brought national and international attention to the desire to amend U.S. hate crime legislation at both the state and federal levels.[8] Wyoming hate crime laws at the time did not recognize homosexuals as a suspect class,[9] whereas Texas had no hate crimes law at all.[10]

Supporters of an expansion of hate crime laws argued that hate crimes are worse than regular crimes without a prejudiced motivation from a psychological perspective. The time it takes to mentally recover from a hate crime is almost twice as long than it is for a regular crime and gay people often feel as if they are being punished for their sexuality which leads to higher incidence of depression, anxiety, and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder [11] They also cited the response to Shepard's murder by many homosexuals, especially youth, who reported going 'back into the closet', fearing for their safety, experiencing a strong sense of self-loathing, and upset that the same thing could happen to them because of their sexual orientation [11]

Background

The 1969 federal hate-crime law (18 U.S.C. § 245(b)(2)) extends to crimes motivated by actual or perceived race, color, religion, or national origin, and only while the victim is engaging in a federally-protected activity, like voting or going to school.[12] Penalties, under both the existing law and the LLEHCPA (Local Law Enforcement Hate Crimes Prevention Act, originally called the "Local Law Enforcement Enhancement Act"), for hate crimes involving firearms are prison terms of up to 10 years, while crimes involving kidnapping, sexual assault, or murder can bring life in prison. In 1990, Congress passed the Hate Crimes Statistics Act which allowed the government to count the incidence of hate crimes based on religion, race, national origin, and sexual orientation. However, a sentence was added on to the end of bill stating that federal funds should not be used to “promote or encourage homosexuality.”[13]

According to FBI statistics, of the over 113,000 hate crimes since 1991, 55% were motivated by racial bias, 17% by religious bias, 14% sexual orientation bias, 14% ethnicity bias, and 1% disability bias.[14][11]

Though not necessarily on the same scale as Matthew Shepard’s murder, violent incidences against gays and lesbians occur frequently. Gay and lesbian people are often verbally abused, assaulted both physically and sexually, and threatened not just by peers and strangers, but also by family members. [15] One study of 192 gay men aged 14-21 found that approximately 1/3 reported being verbally assaulted by at least one family member when they came out and another 10% reported being physically assaulted. [16] Gay and lesbian youth are particularly prone to victimization. A nationwide study of over 9000 gay high school students, 24% of gay men reported being victimized at least 10 times per year because of their sexual orientation; 11% of homosexual women reported the same thing.[16] Victims often experience severe depression, a sense of helplessness, low self-esteem, and frequent suicidal thoughts.[17] Gay youth are two to four times more likely to be threatened with a deadly weapon at school and miss more days of school than their heterosexual peers. Further, they are two to seven times more likely to attempt suicide. These issues, the societal stigma around homosexuality and fear of bias-motivated attack, lead to gay men and women, especially teenagers, becoming more likely to abuse drugs such as marijuana and cocaine and alcohol, have unprotected sex with multiple sexual partners, find themselves in unwanted sexual situations, have body image and eating disorders, and be at higher risk for STDs and HIV/AIDS.[16]

The Act was supported by thirty-one state Attorneys General and over 210 national law enforcement, professional, education, civil rights, religious, and civic organizations, including the AFL-CIO, the American Medical Association, the American Psychological Association, and the NAACP.[18] A November 2001 poll indicated that 73% of Americans were in favor of hate-crime legislation covering sexual orientation.[19]

The LLEHCPA was introduced in substantially similar form in each Congress since the 105th Congress in 1999. The 2007 bill expanded on the earlier versions by including transgender provisions and making it explicit that the law should not be interpreted to restrict people's freedom of speech or association.[20]

Opposition

James Dobson, founder of the socially conservative lobbying group Focus on the Family, opposed the Act, arguing that it would effectively "muzzle people of faith who dare to express their moral and biblical concerns about homosexuality."[12] However, HR 1592 contains a "Rule of Construction" which specifically provides that "Nothing in this Act...shall be construed to prohibit any expressive conduct protected from legal prohibition by, or any activities protected by the free speech or free exercise clauses of, the First Amendment to the Constitution."[21]

Senator Jeff Sessions, among other Senators, was concerned that the bill would not protect all individuals equally.[22] Senator Jim DeMint of South Carolina spoke against the bill, saying that it was unnecessary, that it violated the 14th Amendment, and that it would be a step closer to the prosecution of "thought crimes". He also claimed that it wouldn't help white people if they were victims of a hate crime.[23] Four members of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights wrote a letter stating their opposition to the bill, citing concerns of double jeopardy.[24]

Legislative progress

107th to 109th congress

The bill was first introduced into the 107 Congress's House of Representatives on April 3, 2001, by Rep. John Conyers and was referred to the Subcommittee on Crime. The bill died when it failed to advance in the committee.

It was reintroduced by Rep. Conyers in the 108th and 109th congresses (on April 22, 2004 and May 26, 2005, respectively). As previously, it died both times when it failed to advance in committee.

Similar legislation was introduced by Sen. Gordon H. Smith (R-OR) as an amendment to the Ronald W. Reagan National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2005 (S. 2400) on June 14, 2004. Though the amendment passed the U.S. Senate by a vote of 65-33,[25] the amendment was later removed by conference committee.

110th Congress

See also: 110th United States CongressThe bill was introduced for the fourth time into the House on March 30, 2007, by Conyers. The 2007 version of the bill added gender identity to the list of suspect classes for prosecution of hate crimes. The bill was again referred to the Subcommittee on Crime, Terrorism and Homeland Security.

The bill passed the subcommittee by voice vote and the full House Judiciary Committee by a vote of 20–14. The bill then proceeded to the full House, where it was passed on May 3, 2007, with a vote of 237–180 with Representative Barney Frank, one of two openly gay members of the House at the time, presiding.[26]

The bill then proceeded to the U.S. Senate, where it was introduced by Senator Ted Kennedy and Senator Gordon Smith on April 12, 2007. It was referred to the Senate Judiciary Committee. The bill died when it failed to advance in the Senate committee.

On July 11, 2007, Kennedy attempted to introduce the bill again as an amendment to the Senate Defense Reauthorization bill (H.R. 1585). The Senate hate crime amendment had 44 cosponsors, including four Republicans. After Republicans staged a filibuster on a troop-withdrawal amendment to the defense bill, Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid delayed the votes on the hate crime amendment and the defense bill until September.[27]

The bill passed the Senate on September 27, 2007, as an amendment to the Defense Reauthorization bill. The cloture vote was 60–39 in favor. The amendment was then approved by voice vote.[28] President Bush indicated he might veto the DoD authorization bill if it reached his desk with the hate crimes legislation attached.[29][30] Ultimately, the amendment was dropped by the Democratic leadership because of opposition from antiwar Democrats, conservative groups, and Bush.[31]

In late 2008, then-President-elect Barack Obama's website stated that one of the goals of his new administration would be to see the bill passed.[32]

111th Congress

See also: 111th United States CongressHouse

Conyers introduced the bill for the fifth time into the House on April 2, 2009. In his introductory speech, he claimed that many law enforcement groups, such as the International Association of Chiefs of Police, the National Sheriffs Association and 31 state Attorneys General support the bill[33] and that the impact hate violence has on communities justifies federal involvement.[34]

The bill was immediately referred to the full Judiciary Committee, where it passed by a vote of 15–12 on April 23, 2009.[35]

On April 28, 2009, Rep. Mike Honda (D-CA) claimed that if the bill were passed it may help prevent the murders of transgendered Americans, such as the murder of Angie Zapata.[36] Conversely, Rep. Steve King (R-IA) claimed that the bill was an expansion of a category of "thought crimes" and compared the bill to the book Nineteen Eighty-Four.[37] That same day, the House Rules Committee allowed one hour and 20 minutes for debate.[38]

The bill then moved to the full House, for debate. During the debate, Rep. Jan Schakowsky (D-IL) claimed that the bill would help prevent murders such as those of spree killer Benjamin Nathaniel Smith and would take "an important step" towards a more just society.[39] After the vote, Rep. Trent Franks (R-AZ) claimed that equal protection regardless of status is a fundamental premise of the nation and thus the bill is unnecessary, and that, rather, it would prevent religious organizations from expressing their beliefs openly (although the bill only refers to violent actions, not speech.)[40]

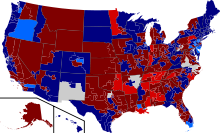

The bill passed the House on April 29, 2009, by a vote of 249–175, with support from 231 Democrats and 18 Republicans, including Republican Main Street Partnership members Judy Biggert (IL), Mary Bono Mack (CA), Joseph Cao (LA), Mike Castle (DE), Charlie Dent (PA), Lincoln Diaz-Balart (FL), Mario Diaz-Balart (FL), Rodney Frelinghuysen (NJ), Jim Gerlach (PA), Mark Kirk (IL), Leonard Lance (NJ), Frank LoBiondo (NJ), Todd Russell Platts (PA), Dave Reichert (WA), and Greg Walden (OR) along with Bill Cassidy (LA), Mike Coffman (CO), and Ileana Ros-Lehtinen (FL).[41]

On April 30, 2009, Rep. Todd Tiahrt (R-KS) compared the bill to the novel Animal Farm and claimed it would harm free speech.[42] Rep. George Miller (D-CA) and Rep. Dutch Ruppersberger (D-MD) both announced that they were unable to be present for the vote, but had they been present they would each have voted in favor.[43][44] Conversely, Rep. Michael Burgess (R-TX) claimed federal law was already sufficient to prevent hate crimes and said that had he been present he would have voted against the bill.[45]

On October 8, 2009, the House passed the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act as part of the conference report on Defense Authorization for fiscal year 2010.[46] The vote was 281-146, with support from 237 Democrats and 44 Republicans.[41]

Senate

The bill again proceeded to the Senate, where it was again introduced by Kennedy on April 28, 2009.[47] The Senate version of the bill had 45 cosponsors as of July 8, 2009.[48]

On June 25, 2009, the Senate Judiciary Committee held a hearing on the bill. Attorney General Eric Holder testified in support of the bill, the first time a sitting Attorney General has ever testified in favor of the bill.[49] During his testimony, Holder mentioned his previous testimony on a nearly identical bill to the senate in July 1998 (the Hate Crimes Prevention Act of 1998, S.1529), just months before Matthew Shepard was murdered.[50] According to CNN, Holder testified that, "more than 77,000 hate crime incidents were reported by the FBI between 1998 and 2007, or 'nearly one hate crime for every hour of every day over the span of a decade.'" Holder emphasized that one of his "highest personal priorities ... is to do everything I can to ensure this critical legislation finally becomes law."[51]

Reverend Mark Achtemeier of the University of Dubuque Theological Seminary, Janet Langhart, whose play was premiering at the United States Holocaust Museum at the time of the shooting earlier in the month and Michael Lieberman of the Anti-Defamation League also testified in favor of the bill. Gail Heriot of the United States Commission on Civil Rights and Brian Walsh of the Heritage Foundation testified in opposition to the bill.

The Matthew Shepard Act was adopted as an amendment to S. 1390 (the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2010) by a 63-28 cloture vote on July 15, 2009.[52] At the request of Senator Jeff Sessions (an opponent of the Matthew Shepard Act), an amendment was added to the Senate version of the hate crimes legislation that would have allowed prosecutors to seek the death penalty for hate crime murders,[53] though the amendment was later removed in conference with the House.[54]

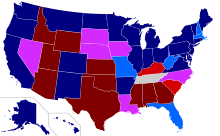

The bill won the support of five Republicans: Susan Collins (ME), Dick Lugar (IN), Lisa Murkowski (AK), Olympia Snowe (ME), and George Voinovich (OH).

Passage

The bill passed the Senate when the Defense bill passed on July 23, 2009.[55] As originally passed, the House version of the defense bill did not include the hate crimes legislation, requiring the difference to be worked out in a Conference committee. On October 7, 2009, the Conference committee published the final version of the bill, which included the hate crimes amendment;[56] the conference report was then passed by the House on October 8, 2009.[57] On October 22, 2009, following a 64-35 cloture vote,[58][59] the conference report was passed by the Senate by a vote of 68-29.[60] The bill was signed into law on the afternoon of October 28, 2009 by President Barack Obama.[2]

Legislative History

Congress Short title Bill number Date introduced Sponsor # of cosponsors Latest status 107th Congress Local Law Enforcement Hate Crimes Prevention Act of 2001 H.R. 1343 April 3, 2001 Rep. John Conyers (D-MI) 208 Died in the House Subcommittee on Crime S. 625 March 27, 2001 Sen. Ted Kennedy (D-MA) 50 Failed cloture motion 54-43 108th Congress Local Law Enforcement Hate Crimes Prevention Act of 2004 H.R. 4204 April 22, 2004 Rep. John Conyers (D-MI) 178 Died in the House Subcommittee on Crime, Terrorism, and Homeland Security S.Amdt. 3183 to S. 2400 June 14, 2004 Sen. Gordon H. Smith (R-OR) 4 Passed in the Senate (65-33) as an amendment to the Ronald W. Reagan National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2005 S. 2400

Removed from conference report109th Congress Local Law Enforcement Hate Crimes Prevention Act of 2005 H.R. 2662 May 26, 2005 Rep. John Conyers (D-MI) 159 Died in the House Subcommittee on Crime, Terrorism, and Homeland Security S. 1145 May 26, 2005 Sen. Ted Kennedy (D-MA) 45 Died in the Senate Judiciary Committee 110th Congress Local Law Enforcement Hate Crimes Prevention Act of 2007 H.R. 1592 March 30, 2007 Rep. John Conyers (D-MI) 171 Passed the House (237-180) S. 1105 April 12, 2007 Sen. Ted Kennedy (D-MA) 44 Died in the Senate Judiciary Committee 111th Congress Local Law Enforcement Hate Crimes Prevention Act of 2009 H.R. 1913 April 2, 2009 Rep. John Conyers (D-MI) 120 Passed the House (249-175) as an amendment to the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2010 H.R. 2647. S. 909 April 28, 2009 Sen. Ted Kennedy (D-MA) 45 Died in the Senate Judiciary Committee (after the Leahy version passed) S.Amdt. 1511 to S. 1390 July 15, 2009 Sen. Patrick Leahy (D-VT) 37 Passed in the Senate (63-28) as an amendment to the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2010.[55] Signed into law October 28, 2009 by President Barack Obama. Enforcement

In May 2011, a man in Arkansas pled guilty under the Act to running a car containing five Hispanic men off the road. As a result, he became the first person ever convicted under the Act. A second man involved in the same incident was later convicted under the Act but has asked for a new trial.[61][62]

In August 2011, one man plead guilty to branding a swastika into the arm of a developmentally disabled man of Navajo descent. A second man entered a guilty plea to conspiracy to commit a federal hate crime. The two men were accused of branding the victim, shaving a swastika into his head, and writing the words "white power" and the acronym "KKK" on his body. A third man in June 2011, entered a guilty plea to conspiracy to commit a federal hate crime. All three men were charged under the Act in December of 2010. [63]

See also

References

- ^ Matthew Shepard Hate Crimes Act passes Congress, finally

- ^ a b President Barack Obama signs hate crimes legislation into law

- ^ Obama Signs Defense Policy Bill That Includes 'Hate Crime' Legislation

- ^ http://www.hrc.org/laws_and_elections/5660.htm

- ^ "Hate Crimes Protections 2007". National Gay and Lesbian Task Force. Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. http://web.archive.org/web/20070927043549/http://www.thetaskforce.org/issues/hate_crimes_main_page/2007_legislation. Retrieved 2009-12-09.

- ^ "It's Official: First Federal Law to Protect Transgender People". National Center for Transgender Equality. http://www.transequality.org/news09.html#first_law.

- ^ a b c Boven, Joseph (2009-10-09). "Matthew Shepard Hate Crimes Act passes despite GOP opposition". The Colorado Independent. http://coloradoindependent.com/39849/matthew-shepard-hate-crimes-act-passes-despite-gop-opposition. Retrieved 2009-10-10. "one of whom now admits to targeting Shepard for being gay"

- ^ "Repräsentantenhaus will härtere Strafen bei «Hass-Verbrechen»". Tages-Anzeiger. 2009-09-10. http://www.tagesanzeiger.ch/ausland/amerika/Repraesentantenhaus-will-haertere-Strafen-bei-HassVerbrechen/story/19405418. Retrieved 2009-10-10.

- ^ "State Hate Crimes / Statutory Provisions". Anti-Defamation League. 2009-10-10. http://www.adl.org/99hatecrime/provisions.asp.

- ^ Elizondo, Stephanie (1999-06-08). "Black leaders honor Byrd Jr.". Associated Press. Laredo Morning Times. p. 4A. http://airwolf.lmtonline.com/news/archive/0608/pagea4.pdf. Retrieved 2009-10-10.

- ^ a b c "The Ripple Effect of the Matthew Shepard Murder: Impact on the Assumptive World Theory.". American Behavioral Scientist. 2002. http://abs.sagepub.com/cgi/reprint/46/1/27.

- ^ a b Stout, D. House Votes to Expand Hate Crime Protection, New York Times, 2007-05-03. Retrieved 2007-05-03.

- ^ "Gay Adolescents and Suicide: Understanding the Association.". American Behavioral Scientist. 2002. http://abs.sagepub.com/cgi/reprint/46/1/173.

- ^ Abrams, J. House Passes Extended Hate Crimes Bill, Associated Press, 2007-05-03. Retrieved on 2007-05-03.

- ^ "Sexual Orientation and Adolescents.". Pediatricsdate=2004. http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/cgi/content/full/113/6/1827.

- ^ a b c "Gay Adolescents and Suicide: Understanding the Association.". Adolescence. 2005. http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m2248/is_159_40/ai_n15950408/.

- ^ "Sexual Orienation and Mental Health.". Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2007. http://arjournals.annualreviews.org/doi/abs/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091510.

- ^ Supporters for this legislation, Human Rights Campaign. Retrieved 05-03-2007.

- ^ The Local Law Enforcement Hate Crimes Prevention Act / Matthew Shepard Act, Human Rights Campaign. Retrieved 2007-09-27.

- ^ Questions and Answers: The Local Law Enforcement Hate Crimes Prevention Act, Human Rights Campaign. Retrieved on 2007-05-04.

- ^ Text of H.R. 1592 "Referred to Senate Committee after being Received from House" as accessed on 2007-10-02; the text of S. 1105 accessed on the same date does not include this section.

- ^ USDOJ.gov

- ^ Nasaw, Daniel (23 October 2009). "Judges barred from demanding doctor's notes in transgender name change cases". The Guardian.

- ^ open letter

- ^ Roll call vote 114, via Senate.gov

- ^ Simon, R. Bush threatens to veto expansion of hate-crime law, Los Angeles Times, 2007-05-03. Retrieved on 2007-05-03.

- ^ Chibbaro, Lou (2007-07-26). "Hate crimes bill in limbo". Washington Blade. Archived from the original on 2007-09-28. http://web.archive.org/web/20070928012004/http://www.washblade.com/thelatest/thelatest.cfm?blog_id=13543.

- ^ HRC | Senate Passage of Hate Crimes Bill Moves Bill Closer Than Ever To Becoming Law

- ^ Statement of Administration Policy, Executive Office of the President, Office of Management and Budget. Retrieved 2007-05-09.

- ^ US Senate passes gay hate crimes law, PinkNews.co.uk.

- ^ Wooten, Amy (January 1, 2008). "Congress Drops Hate-Crimes Bill". Windy City Times. http://www.windycitymediagroup.com/gay/lesbian/news/ARTICLE.php?AID=17078. Retrieved July 31, 2008.

- ^ "Plan to Strengthen Civil Rights". The Office of the President-Elect. http://change.gov/agenda/civil_rights_agenda/. Retrieved February 18, 2009.

- ^ "Introduction of the Local Law Enforcement Hate Crimes Prevention Act of 2009". 2009-04-02. http://frwebgate.access.gpo.gov/cgi-bin/getpage.cgi?dbname=2009_record&page=E878&position=all. Retrieved 2009-06-18.

- ^ "Introduction of the Local Law Enforcement Hate Crimes Prevention Act of 2009". 2009-04-02. http://frwebgate.access.gpo.gov/cgi-bin/getpage.cgi?dbname=2009_record&page=E879&position=all. Retrieved 2009-06-18.

- ^ "Matthew Shepard Act Wins Approval from Judiciary Committee". http://lezgetreal.com/?p=9708/. Retrieved 2009-04-25.

- ^ "Expressing Support for "Local Law Enforcement Hate Crimes Prevention Act (LLEHCPA)/Matthew Shepard Act"". 2009-04-28. http://frwebgate.access.gpo.gov/cgi-bin/getpage.cgi?dbname=2009_record&page=E1004&position=all. Retrieved 2009-06-21.

- ^ . IowaPolitics.com. 2009-04-28. http://www.iowapolitics.com/index.iml?Article=156914. Retrieved 2009-06-18.

- ^ "H.R. 1913 – Local Law Enforcement Hate Crimes Prevention Act of 2009". United States House of Representatives Committee on Rules. 2009-04-28. http://www.rules.house.gov/SpecialRules_details.aspx?NewsID=4233. Retrieved 2009-06-18.

- ^ "Local Law Enforcement Hate Crimes Prevention Act of 2009". 2009-04-30. http://frwebgate.access.gpo.gov/cgi-bin/getpage.cgi?dbname=2009_record&page=E1035&position=all. Retrieved 2009-06-21.

- ^ "The Passage of the Local Law Enforcement Hate Crimes Prevention Act". 2009-04-29. http://frwebgate.access.gpo.gov/cgi-bin/getpage.cgi?dbname=2009_record&page=H4972&position=all. Retrieved 2009-06-21.

- ^ a b Roll call vote 223, via Clerk.House.gov

- ^ "All People Are Equal". 2009-04-30. http://frwebgate.access.gpo.gov/cgi-bin/getpage.cgi?dbname=2009_record&page=H5046&position=all. Retrieved 2009-06-21.

- ^ "Personal Explanation". 2009-04-30. http://frwebgate.access.gpo.gov/cgi-bin/getpage.cgi?dbname=2009_record&page=E1024&position=all. Retrieved 2009-06-21.

- ^ "Personal Explanation". 2009-04-30. http://frwebgate.access.gpo.gov/cgi-bin/getpage.cgi?dbname=2009_record&page=E1044&position=all. Retrieved 2009-06-21.

- ^ "Personal Explanation". 2009-04-30. http://frwebgate.access.gpo.gov/cgi-bin/getpage.cgi?dbname=2009_record&page=E1037&position=all. Retrieved 2009-06-21.

- ^ "Final Vote Results for Role Call 223". Speaker of the United States House of Representatives. 2009-10-10. http://www.speaker.gov/newsroom/legislation?id=0341. Retrieved 2009-10-10.

- ^ Matthew Shepard Hate Crimes Prevention Act Introduced in Senate

- ^ Search Results - THOMAS (Library of Congress)

- ^ "Senate Hate Crimes Hearing at 10am « HRC Back Story:". 2009-06-25. http://www.hrcbackstory.org/2009/06/senate-hate-crimes-hearing-at-10am/. Retrieved 2009-06-28.

- ^ Garcian, Michelle (2008-01-01). "AG to Senate: Pass Hate Crime Bill". The Advocate. http://www.advocate.com/article.aspx?id=83564. Retrieved 2008-06-28.

- ^ "CNN Political Ticker: All politics, all the time Blog Archive - Holder pushes hate crimes law; GOP unpersuaded « - Blogs from CNN.com:". 2009-06-25. http://politicalticker.blogs.cnn.com/2009/06/25/holder-pushes-hate-crimes-law-gop-unpersuaded/#more-57796. Retrieved 2009-06-28.

- ^ Eleveld, Kerry (2009-07-17). "Hate Crimes Passes, Faces Veto". The Advocate. http://www.advocate.com/News/Daily_News/2009/07/16/Hate_Crimes_Passes,_Faces_Veto/. Retrieved 2009-07-17.

- ^ Rushing, J. Taylor (2009-07-20). "Hate Crimes Amendments Pass Easily". The Hill. http://thehill.com/leading-the-news/hate-crimes-amendments-pass-easily-2009-07-20.html. Retrieved 2009-07-21.

- ^ "Hate Crimes Act Makes Conference Report, Death Penalty Gone". lawdork.net. 2009-10-08. http://lawdork.net/2009/10/08/hate-crimes-act-makes-conference-report-death-penalty-gone/.

- ^ a b Senate.gov

- ^ "HRC Backstory: Conference Report Published – Hate Crimes Bill Included". http://www.hrcbackstory.org/2009/10/conference-report-published-hate-crimes-bill-included/.

- ^ "AFP: US lawmakers pass 680-billion-dollar defense budget bill". http://www.google.com/hostednews/afp/article/ALeqM5hkAXS0HTzkXeKMKJ8BFxiuculsPA.

- ^ "HRC Backstory: Senate Achieves Cloture on DoD Conference Report Including Hate Crimes Provision". http://www.hrcbackstory.org/2009/10/senate-achieves-cloture-on-dod-conference-report-including-hate-crimes-provision/.

- ^ Roll call vote

- ^ Roxana Tiron, "Senate OKs defense bill, 68-29," The Hill, found at The Hill website. Accessed October 22, 2009.

- ^ Fry, Lindsey (23 May 2011). "Man Accused of Violating the Hate Crime Prevention Act". KATV. http://www.katv.com/story/14663862/man-accused-of-violating-the-hate-crime-prevention-act. Retrieved 29 June 2011.

- ^ Moody, Leigh (June 7, 2011). "Man Convicted of Federal Hate Crime Wants a New Trial". KSPR. http://articles.kspr.com/2011-06-07/guilty-verdict_29632161. Retrieved 29 June 2011.

- ^ "2 Men Plead Guilty In Swastika Branding Case". The Huffington Post. 2011-08-18. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2011/08/18/2-men-plead-guilty-in-swa_n_930827.html.

External links

- H.R. 1592, the House bill

- S. 1105, the Senate bill

- South Carolina Senator Jim DeMint's speech. Flash video on YouTube. 16 July 2009. 12 minutes.

- Text of floor speeches by Senators Kennedy, Bayh, and Schumer introducing the bill in the Senate on April 12, 2007

- Final form of Matthew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act

Social policy in the United States Abortion Abortion in the United States States' policies Abortion in the US (state by state)US Supreme Court cases Griswold v. Connecticut (1965) • Roe v. Wade (1973) • Doe v. Bolton (1973) • Harris v. McRae (1980) • Webster v. Reproductive Health Services (1989) • Planned Parenthood v. Casey (1992) • Scheidler v. National Organization for Women (2006) • Gonzales v. Carhart (2007)Federal legislation Hyde Amendment (1976) • Freedom of Access to Clinic Entrances Act (1994) • Born-Alive Infants Protection Act (2002) • Partial-Birth Abortion Ban Act of 2003 • Unborn Victims of Violence Act (2004)Affirmative action Affirmative action in the United States Supreme Court decisions Brown v. Board of Education (1954) • Regents of the University of California v. Bakke (1978) • United Steelworkers v. Weber (1979) • Fullilove v. Klutznick (1980) • Wygant v. Jackson Board of Education (1986) • City of Richmond v. J.A. Croson Co. (1989) • Adarand Constructors, Inc. v. Peña (1995) • Grutter v. Bollinger (2003) • Gratz v. Bollinger (2003) • Parents v. Seattle (2007) • Ricci v. DeStefano (2009)Federal legislation and edicts Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment (1868) • Executive Order 10925 (1961) • Civil Rights Act of 1964 • Executive Order 11246 (1965)State initiatives Proposition 209 (CA, 1996) • Initiative 200 (WA, 1998) • Proposal 2 (MI, 2006) • Initiative 424 (NE, 2008)People Alcohol Alcohol policy in the United States Prohibition Related articles State laws List of alcohol laws of the United States by state States - Alabama

- Alaska

- Arizona

- Arkansas

- California

- Colorado

- Connecticut

- Delaware

- Florida

- Georgia

- Hawaii

- Idaho

- Illinois

- Indiana

- Iowa

- Kansas

- Kentucky

- Louisiana

- Maine

- Maryland

- Massachusetts

- Michigan

- Minnesota

- Mississippi

- Missouri

- Montana

- Nebraska

- Nevada

- New Hampshire

- New Jersey

- New Mexico

- New York

- North Carolina

- North Dakota

- Ohio

- Oklahoma

- Oregon

- Pennsylvania

- Rhode Island

- South Carolina

- South Dakota

- Tennessee

- Texas

- Utah

- Vermont

- Virginia

- Washington

- West Virginia

- Wisconsin

- Wyoming

Cannabis Legality of cannabis in the United States Cannabis decriminalized Alaska • California • Colorado • Maine • Massachusetts • Minnesota • Mississippi • Nebraska • New York • North Carolina • Ohio • OregonMedical cannabis legal Alaska • Arizona • California • Colorado • Hawaii • Maine • Michigan • Montana • Nevada • New Jersey • New Mexico • Oregon • Rhode Island • Vermont • Washington • Washington, D.C.Related articles GeneralCannabis in the United States • Legal history of cannabis • Places that have decriminalized non-medical cannabis • Decriminalization of non-medical cannabisCasesDeath penalty Capital punishment in the United States In depth Federal Government · Military · Alabama · Arkansas · California · Colorado · Connecticut · Florida · Idaho · Indiana · Louisiana · Maine · Maryland · Massachusetts · Michigan · Mississippi · Nebraska · Nevada · New Hampshire · New Jersey · New Mexico · New York · Ohio · Oklahoma · Oregon · Rhode Island · South Dakota · Texas · Utah · Vermont · Virginia · Washington · West Virginia · Wisconsin · WyomingLists of individuals executed Alabama · Arizona · Arkansas · California · Colorado · Connecticut · Delaware · Florida · Georgia · Idaho · Illinois · Indiana · Kansas · Kentucky · Louisiana · Maryland · Michigan · Mississippi · Missouri · Montana · Nebraska · Nevada · New Hampshire · New Jersey · New Mexico · New York · North Carolina · Ohio · Oklahoma · Oregon · Pennsylvania · South Carolina · South Dakota · Tennessee · Texas · Utah · Virginia · Washington · WyomingOther Gun control Same-sex marriage Same-sex marriage status in the United States by state - Same-sex marriage law in the United States by state - Defense of Marriage Act - Marriage Protection Act - State amendments banning same-sex unionsSame-sex unions in the United States Main articles: State constitutional amendments banning (List by type) - Public opinion (Opponents - List of supporters) - Status by state (Law - Legislation) - Municipal domestic partnership registriesSame-sex marriage legalized: Connecticut - District of Columbia - Iowa - Massachusetts - New Hampshire - New York - Vermont - Coquille, SuquamishSame-sex marriage recognized,

but not performed:California*# - MarylandCivil union or domestic partnership legal: California - Colorado - Delaware - District of Columbia - Hawaii - Illinois - Maine - Maryland - Nevada - New Jersey - Oregon - Rhode Island - Washington - WisconsinSame-sex marriage prohibited by statute: Delaware - Hawaii - Illinois - Indiana - Maine - Maryland - Minnesota - North Carolina - Pennsylvania - Puerto Rico - Washington - West Virginia - WyomingSame-sex marriage prohibited

by constitutional amendment:Alaska - Arizona - California# - Colorado - Mississippi - Missouri - Montana - Nevada - Oregon - TennesseeAll types of same-sex unions prohibited

by constitutional amendment:Recognition of same-sex unions undefined

by statute or constitutional amendment:American Samoa - Guam - New MexicoNotes:

*All out-of-state same-sex marriages are given the benefits of marriage under California law, although only those performed before November 5, 2008, are granted the designation "marriage".

# California's ban on same-sex marriage remains in limbo following a federal case finding the ban unconstitutional, which is stayed pending appeal to the Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit.Other issues Part of a series on LGBT rights in the United States By entity Alabama · Alaska · Arizona · Arkansas · California · Colorado · Connecticut · Delaware · Florida · Georgia · Hawaii · Idaho · Illinois · Indiana · Iowa · Kansas · Kentucky · Louisiana · Maine · Maryland · Massachusetts · Michigan · Minnesota · Mississippi · Missouri · Montana · Nebraska · Nevada · New Hampshire · New Jersey · New Mexico · New York · North Carolina · North Dakota · Ohio · Oklahoma · Oregon · Pennsylvania · Rhode Island · South Carolina · South Dakota · Tennessee · Texas · Utah · Vermont · Virginia · Washington · West Virginia · Wisconsin · WyomingInsular area

By type Same-sex unions (Marriage · Civil union · Domestic partnership (by municipal areas)) · Sexual orientation and the United States military (Don't ask, don't tell · 2010 repeal)Nationwide

precedentsState amendments banning same-sex unions (Defense of Marriage Act) · Hate crime laws in the United States (Matthew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act) · Sodomy laws in the United States (Lawrence v. Texas)See also Categories:- Hate crime

- LGBT rights in the United States

- Discrimination law in the United States

- Discrimination in the United States

- LGBT law in the United States

- 109th United States Congress

- 110th United States Congress

- 111th United States Congress

- 2007 in law

- 2007 in LGBT history

- 2009 in law

- 2009 in LGBT history

- Matthew Shepard

- Presidency of Barack Obama

- United States federal civil rights legislation

- United States federal criminal legislation

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.